Abstract

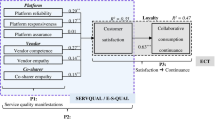

Ridesharing platforms compensate drivers using a fixed commission system that does not systematically reward effective drivers, which reduces platform engagement. Unsurprisingly, driver transaction activity is intermittent and service unpredictable. Influenced by agency theory, we propose a variable commission that jointly accounts for drivers’ transactions and service performance. To alleviate disengagement, we propose a customer-oriented engagement framework that challenges the notion of the sole monetary focus of drivers. We compare the effects of variable and fixed commission schemes on consequences such as driver net revenue and referral value, mediated by attitudinal outcomes. In a 3-month cluster-randomized field experiment with 3,367 ridesharing drivers across 16 cities and two population tiers, we show improvements in driver satisfaction and emotional connectedness accentuated by goal-oriented feedback. Variable commission with goal-oriented feedback translates to a 24.5% rise in revenue, a 19.5% increase in referral value, and a 43.21% lower churn. A cost–benefit analysis reinforces these results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Intra-component items are equally weighted to avoid a constraint on measures. Taking our approach as an initial exploration, these weights are best determined by platforms based on usage data. The flexibility of altering weights allows the SPES to be generalized to other verticals.

In experimental cities, the platform communicated the change in the commission scheme to the drivers through the mobile app on three occasions: thirteen, seven, and three days before the experiment. The platform also communicated the 25% commission to the control city drivers in the same way and at the same times to avoid confounding bias. On each occasion, the drivers acknowledged receipt of the message in the app.

As the discussed engagement approach suggests, direct contribution is affected by satisfaction only, while indirect contribution is influenced by emotion only. We empirically verified the differences in emotional connectedness and satisfaction to be statistically insignificant in the direct (6) and indirect (7) contribution equations. Similarly, we tested for the potential effects among satisfaction and emotion by adding emotional connectedness (base value) in Eq. 4 and satisfaction (base value) in Eq. 5. Both are statistically insignificant. Finally, since the errors of satisfaction and emotional connectedness could be correlated within an individual, we used seemingly unrelated regression (SUR).

The first stage moderated mediation is derived from the simple equations \(\widehat{M}={a}_{0}+{a}_{1}X+{a}_{2}Z+{a}_{3}XZ+{e}_{m}\) and \(\widehat{Y}={b}_{0}+{b}_{1}M+{b}_{2}X+{e}_{y}\). Substituting \(\widehat{M}\), we have \(\widehat{Y}={b}_{0}+{a}_{0}{b}_{1}+\left({a}_{1}{b}_{1}+{a}_{3}{b}_{1}Z\right)X+{a}_{2}{b}_{1}Z+{b}_{2}X+{e}_{y}+{{b}_{1}e}_{m}\) where \(\left({a}_{1}{b}_{1}+{a}_{3}{b}_{1}Z\right)\) denotes X’s conditional indirect effect on Y and \({b}_{2}\) denotes X’s direct effect on Y. As depicted with \({\upbeta }_{3}\) and \({\upbeta }_{4}\), the direct effects are insignificant. The indirect effects of the treatment on direct and indirect contributions are significant as per Preacher and Hayes’ (2008) bootstrap script test, and their effects are shown in Figures WA.9a and WA.9b. Overall, we observed indirect-only moderated mediations for both the direct and indirect contribution paths.

In the main model, the treatment effect on satisfaction is .486 for drivers with better (p < .01) and -.059 for drivers with worse commission (p < .05), while the treatment effect on emotional connectedness is .502 for the first (p < .01) and .036 for the second group (p < .23).

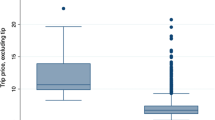

We asked drivers to pick a range for an adjusted commission and found that approximately 10% variation above and below 25% is the most and 0% is the least preferred choice. Our selection of the 15–35% commission range in the field experiment is also consistent with drivers’ fairness perception.

Using an analogy from Uber’s annual report, drivers increased from 464,681 in 2015 to 750,000 in 2018 in the US, an annual increase of 95,106 (Hall and Krueger, 2018; Uber Technologies, 2019). As per the 2019 annual report, driver referral incentives are accounted as customer acquisition costs, which totaled $136 M (Million) in 2018. Payments to drivers attributed to non-driving activities (e.g., marketing expenses for driver acquisition) exceeded the cumulative revenue earned since the inception of the relationship with the driver by $837 M in 2018. Conservatively, the cost of acquisition per driver is $136 M/95,106 = $1,430 with only referral incentives, or $837 M/95,106 = $8,801 including marketing expenses. In our field experiment, 305 drivers churned in three months from four tier A control cities compared to 171 in four tier A treatment cities. Acquisition savings for the difference (134) amounts to 134*1,430 = $191,620 in three months for tier A and $72,930 for tier B. The combined cost savings amount to $264,550.

References

Adam. (2019). What is Didi advance, rewards program that changing the way driver-partners earn. rideshareAUNZ. Retrieved from https://www.rideshareaunz.com/didi-advance-rewards-program-guide-in-australia/. Accessed 23 Sept 2023.

Allon, G., Cohen, M. C., & Sinchaisri, W. P. (2023). The impact of behavioral and economic drivers on gig economy workers. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management. https://doi.org/10.1287/msom.2023.1191

Athey, S., & Imbens, G. W. (2017). The econometrics of randomized experiments. In Handbook of economic field experiments (Vol. 1, pp. 73–140). North-Holland. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.hefe.2016.10.003

Bai, J., So, K. C., Tang, C. S., Chen, X., & Wang, H. (2019). Coordinating supply and demand on an on-demand service platform with impatient customers. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 21(3), 556–570.

Basu, A. K., Lal, R., Srinivasan, V., & Staelin, R. (1985). Salesforce compensation plans: An agency theoretic perspective. Marketing Science., 4(4), 267–291.

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., Nathan DeWall, C., & Zhang, L. (2007). How emotion shapes behavior: Feedback, anticipation, and reflection, rather than direct causation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11(2), 167–203.

Bensinger, G. (2018). Uber Drivers Take Riders the Long Way—at Uber’s Expense. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/uber-drivers-take-riders-the-long-wayat-ubers-expense-1534152602#:~:text=%E2%80%9CIt's%20the%20only%20way%20I,to%20drive%20up%20a%20fare. Accessed 02/01/24.

Bhargava, H. K., & Rubel, O. (2019). Sales force compensation design for two-sided market platforms. Journal of Marketing Research, 56(4), 666–678.

Bimpikis, K., Candogan, O., & Saban, D. (2019). Spatial pricing in ride-sharing networks. Operations Research, 67(3), 744–769.

Bolton, R. N., Kannan, P. K., & Bramlett, M. D. (2000). Implications of loyalty program membership and service experiences for customer retention and value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 95–108.

Bommaraju, R., & Hohenberg, S. (2018). Self-selected sales incentives: Evidence of their effectiveness, persistence, durability, and underlying mechanisms. Journal of Marketing, 82(5), 106–124.

Bosa, D., & Browne, R. (2022). Uber CEO tells staff company will cut down on costs, treat hiring as a ‘privilege’. CNBC. (accessed 08/11/22, Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2022/05/09/uber-to-cut-down-on-costs-treat-hiring-as-a-privilege-ceo-email.html).

Burt, R. S., & Soda, G. (2021). Network capabilities: Brokerage as a bridge between network theory and the resource-based view of the firm. Journal of Management, 47(7), 1698–1719.

Cachon, G. P., Daniels, K. M., & Lobel, R. (2019). The role of surge pricing on a service platform with self-scheduling capacity. In Sharing Economy (pp. 101–113). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01863-4_6

Camacho, N., Nam, H., Kannan, P. K., & Stremersch, S. (2019). Tournaments to crowdsource innovation: The role of moderator feedback and participation intensity. Journal of Marketing, 83(2), 138–157.

Cameron, A. C., Gelbach, J. B., & Miller, D. L. (2008). Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered errors. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(3), 414–427.

Cao, J., Chintagunta, P., & Li, S. (2022). From free to paid: monetizing a non-advertising-based app. Journal of Marketing Research, 60(4), 707–727.

Chakravarty, A., Kumar, A., & Grewal, R. (2014). Customer orientation structure for internet-based business-to-business platform firms. Journal of Marketing, 78(5), 1–23.

Chandar, B., Gneezy, U., List, J. A., & Muir, I. (2019). The drivers of social preferences: Evidence from a Nationwide tipping field experiment (No. w26380). National Bureau of Economic Research - Working Paper. Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w26380/w26380.pdf

Chung, D. J., Steenburgh, T., & Sudhir, K. (2014). Do bonuses enhance sales productivity? A dynamic structural analysis of bonus-based compensation plans. Marketing Science, 33(2), 165–187.

Churchill, G. A. Jr., Ford, N. M., & Walker, O. C. Jr. (1974). Measuring the job satisfaction of industrial salesmen. Journal of Marketing Research, 11(3), 254–260.

Cohen, P., Hahn, R., Hall, J., Levitt, S., & Metcalfe, R. (2016). Using big data to estimate consumer surplus: The case of uber (No. w22627). National Bureau of Economic Research- Working Paper. Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/w22627

Cohen, B., & Kietzmann, J. (2014). Ride on! Mobility business models for the sharing economy. Organization & Environment, 27(3), 279–296.

Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 386.

Cronin, J. J., Jr., & Taylor, S. A. (1992). Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. Journal of Marketing, 56(3), 55–68.

Davalos, J. (2022). Lyft Craters on Plans to Spend More on Driver Incentives. Bloomberg. (accessed 08/11/22, Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-05-03/lyft-revenue-beats-analyst-estimates-on-robust-rideshare-demand).

Eckhardt, G. M., Houston, M. B., Jiang, B., Lamberton, C., Rindfleisch, A., & Zervas, G. (2019). Marketing in the sharing economy. Journal of Marketing, 83(5), 5–27.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57–74.

Fang, Z., Huang, L., & Wierman, A. (2020). Loyalty programs in the sharing economy: Optimality and competition. Performance Evaluation, 143, 102105.

Farrell, D., Fiona G., & Amar H. (2018). The online platform economy in 2018: Drivers, workers, sellers, and lessors. JPMorgan Chase Institute. Retrieved from https://www.jpmorganchase.com/content/dam/jpmc/jpmorgan-chase-and-co/institute/pdf/institute-ope-2018.pdf. Accessed 02/01/24.

Fernández-Loría, C., Cohen, M. C., & Ghose, A. (2019). Evolution of referrals over customers' life cycle: Evidence from a ride-sharing platform. SSRN. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3345669. Accessed 02/01/24.

Fishbach, A., Eyal, T., & Finkelstein, S. R. (2010). How positive and negative feedback motivate goal pursuit. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(8), 517–530.

Fisher, C. D. (2000). Mood and emotions while working: Missing pieces of job satisfaction? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(2), 185–202.

Gillaspia, D., 2020. Uber Rider Rating: Everything you need to know. (accessed 02/11/22, Retrieved from https://www.uponarriving.com/uber-rider-rating/].

Grab. (2023). What is Ka-Grab Rewards Plus. Retrieved from https://help.grab.com/driver/enph/360029607932-What-is-Ka-Grab-Rewards-Plus. Accessed 23 Sept 2023.

Grabar, H. (2022). The Decade of Cheap Rides Is Over. (accessed 03/09/23, Retrieved from https://slate.com/business/2022/05/uber-subsidy-lyft-cheap-rides.html).

Gretz, R. T., Malshe, A., Bauer, C., & Basuroy, S. (2019). The impact of superstar and non-superstar software on hardware sales: The moderating role of hardware lifecycle. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(3), 394–416.

Guda, H., & Subramanian, U. (2017). Strategic pricing and forecast communication on on-demand service platforms. Available at SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2895227

Hall, J. V., & Krueger, A. B. (2018). An analysis of the labor market for Uber’s driver-partners in the United States. Ilr Review, 71(3), 705–732.

Hamari, J., Sjöklint, M., & Ukkonen, A. (2016). The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(9), 2047–2059.

Helling, B. (2018). Ridester’s 2018 Independent Driver Earnings Survey. (accessed 03/22/23, Retrieved from https://www.ridester.com/2018-survey/).

Helling, B. (2022). Uber Rider Ratings: Everything You Need To Know & Succeed. (accessed 08/15/22, Retrieved from https://www.ridester.com/uber-rider-ratings/).

Hirsch, P. M., Friedman, R., & Koza, M. P. (1990). Collaboration or paradigm shift?: Caveat emptor and the risk of romance with economic models for strategy and policy research. Organization Science, 1(1), 87–97.

Hu, W. & Ley, A. (2023). Uber Drivers Say They Are Struggling: ‘This Is Not Sustainable’. (accessed 03/01/23, Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/12/nyregion/cab-uber-lyft-drivers.html).

Jensen, M., & Meckling, W. (1976). Theory of the firm: Management behavior, agency costs and capital structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360.

Jindal, P., Kim, M., & Newberry, P. (2022). Multi-dimensional Salesforce Compensation with Negotiated Prices. Available at SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4046168

Kim, M., Sudhir, K., Uetake, K., & Canales, R. (2019). When salespeople manage customer relationships: Multidimensional incentives and private information. Journal of Marketing Research, 56(5), 749–766.

Kumar, V., Petersen, J. A., & Leone, R. P. (2010). Driving profitability by encouraging customer referrals: Who, when, and how. Journal of Marketing, 74(5), 1–17.

Kumar, V., Lahiri, A., & Dogan, O. B. (2018). A strategic framework for a profitable business model in the sharing economy. Industrial Marketing Management, 69, 147–160.

Kumar, A., Gupta, A., Parida, M., & Chauhan, V. (2022). Service quality assessment of ride-sourcing services: A distinction between ride-hailing and ride-sharing services. Transport Policy, 127, 61–79.

Lahiri, A., Doğan, O. B., & Kumar, V. (2023). Nurturing Platform’s Resource Availability through Nudging Operational Effectiveness in the Ridesharing Vertical of Sharing Economy. Journal of Business Research, 168, 114–121.

Lake, R. (2023). California Assembly Bill 5 (AB5): What's In It and What It Means. (accessed 09/23/23, Retrieved from https://www.investopedia.com/california-assembly-bill-5-ab5-4773201).

Latham, G. P., & Wexley, K. N. (1993). Increasing productivity through performance appraisal. Prentice Hall.

Liu, Y., Xu, N., Yuan, Q., Liu, Z., & Tian, Z. (2022). The relationship between feedback quality, perceived organizational support, and sense of belongingness among conscientious teleworkers. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 806443.

Lo, D., Ghosh, M., & Lafontaine, F. (2011). The incentive and selection roles of sales force compensation contracts. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(4), 781–798.

Locke, E. A., Shaw, K. N., Saari, L. M., & Latham, G. P. (1981). Goal setting and task performance: 1969–1980. Psychological Bulletin, 90(1), 125.

Lyft, Inc. (2019). “2018 in Review: Putting Our Vision Into Action” (accessed 09/23/23, Retrieved from https://www.lyft.com/blog/posts/2018-year-in-review).

Ma, N. F., Yuan, C. W., Ghafurian, M., & Hanrahan, B. V. (2018, April). Using stakeholder theory to examine drivers' stake in Uber. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1–12).

Marinova, D., Ye, J., & Singh, J. (2008). Do frontline mechanisms matter? Impact of quality and productivity orientations on unit revenue, efficiency, and customer satisfaction. Journal of Marketing, 72(2), 28–45.

McGee, C. (2017). Only 4% of Uber drivers remain on the platform a year later, says report. CNBC. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2017/04/20/only-4-percent-of-uber-drivers-remain-after-a-yearsaysreport.html#:~:text=Only%204%20percent%20of%20people,competition%20from%20companies%20like%20Lyft. Accessed 02/01/24.

Mcgregor, M., Brown, B., Glöss, M., & Lampinen, A. (2016). On-demand taxi driving: Labour conditions, surveillance, and exclusion. In The Internet, Policy and Politics Conferences, Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford (Vol. 25201). Retrieved from: http://blogs.oii.ox.ac.uk/ipp-conference/sites/ipp/files/documents/McGregor_Uber%2520paper%2520Sept

Ming, L., Tunca, T. I., Xu, Y., & Zhu, W. (2019). Market formation, pricing, and revenue sharing in ride-hailing services. SSRN. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3338088. Accessed 02/01/24.

Möhlmann, M., Zalmanson, L., Henfridsson, O., & Gregory, R. W. (2021). Algorithmic management of work on online labor platforms: when matching meets control. MIS Quarterly, 45(4). https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2021/15333

Mukhopadhyay, A., & Johar, G. V. (2005). Where there is a will, is there a way? Effects of lay theories of self-control on setting and keeping resolutions. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(4), 779–786.

Oettingen, G., Hönig, G., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2000). Effective self-regulation of goal attainment. International Journal of Educational Research, 33(7–8), 705–732.

Pansari, A., & Kumar, V. (2017). Customer engagement: The construct, antecedents, and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(3), 294–311.

Perri, J. (2018). Uber vs. Lyft: Who’s tops in the battle of U.S. rideshare companies. (accessed 03/22/23, Retrieved from https://secondmeasure.com/datapoints/rideshare-industry-overview/).

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Rao, R. S., Viswanathan, M., John, G., & Kishore, S. (2021). Do Activity-Based Incentive Plans Work? Evidence from a Large-Scale Field Intervention. Journal of Marketing Research, 58(4), 686–704.

SEC, Lyft. (2019a). Annual report pursuant to section 13 or 15(d) of the securities exchange act of 1934. SEC. Retrieved from https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1759509/000175950920000009/lyft-20191231.htm. Accessed 02/01/24.

SEC, Uber. (2019b). Uber Technologies Form S-1 registration statement, SEC (Ed.): SEC. Retrieved from https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1543151/000119312519103850/d647752ds1.htm. Accessed 02/01/24.

Si, L. (2021). Didi Offers Details of Its Income Structure to End Rumors about Excessive Commission. (accessed 09/23/23, Retrieved from https://pandaily.com/didi-offers-details-of-its-income-structure-to-end-rumors-about-excessive-commission/).

Singh, J. (2000). Performance productivity and quality of frontline employees in service organizations. Journal of Marketing, 64(2), 15–34.

Soman, D., & Cheema, A. (2011). Earmarking and partitioning: Increasing saving by low-income households. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(SPL), S14-S22. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.48.SPL.S14

Stremersch, S., Gonzalez, J., Valenti, A., & Villanueva, J. (2023). The value of context-specific studies for marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 51(1), 50–65.

Tellis, G. J., Yin, E., & Niraj, R. (2009). Does quality win? Network effects versus quality in high-tech markets. Journal of Marketing Research, 46(2), 135–149.

Uber-Technologies. (2019). “Uber-Technologies-Inc-2019-Annual-Report”. Retrieved from https://s23.q4cdn.com/407969754/files/doc_financials/2019/ar/Uber-Technologies-Inc-2019-Annual-Report.pdf. Accessed 23 Sept 2023.

Viswanathan, M., Li, X., John, G., & Narasimhan, O. (2018). Is cash king for sales compensation plans? Evidence from a large-scale field intervention. Journal of Marketing Research, 55(3), 368–381.

Waheed, S., Herrera, L., Gonzalez-Vasquez, A. L., Shadduck-Hernández, J., Koonse, T., & Leynov, D. (2018). More than a gig: A survey of ride-hailing drivers in Los Angeles. Retrieved from https://www.labor.ucla.edu/publication/more-than-a-gig/. Accessed 02/01/24.

Zervas, G., Proserpio, D., & Byers, J. W. (2021). A first look at online reputation on Airbnb, where every stay is above average. Marketing Letters, 32(1), 1–16.

Zhang, Y., Bradlow, E. T., & Small, D. S. (2015). Predicting customer value using clumpiness: From RFM to RFMC. Marketing Science, 34(2), 195–208.

Zoepf, S. M., Chen, S., Adu, P., & Pozo, G. (2018). The economics of ride-hailing: Driver revenue, expenses and taxes. CEEPR WP, 5(2018), 1–38.

Acknowledgements

We thank Editor John Hulland and the anonymous review team for their valuable guidance during the revision process.We thank Renu for copyediting the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Dr. Doğan is an Assistant Professor of Marketing at The University of Oklahoma; Dr. Kumar is a Professor of Marketing, and the Goodman Academic-Industry Partnership Professor at Brock University; Distinguished Fellow of MICA, and the Chang Jiang Scholar of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (HUST); Dr. Lahiri is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Marketing at the Stavanger Business School.

Neil Morgan served as Area Editor for this article

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix 1: Determining the platform’s commission using SPES

Appendix 1: Determining the platform’s commission using SPES

At the time of this study, the focal ridesharing platform took 25% commission from the revenue drivers generate with each ride, and the remaining 75% is the driver’s compensation. We use SPES to alter this commission based on the individual driver’s performance relative to all the platform’s available drivers in a city, throughout the month. A higher SPES translates to a lower platform commission, and thereby to a higher driver compensation. The commission needs to revolve closer to the rate in practice (i.e., 25%) to preserve feasibility and the platform’s revenue generation targets. Considering the platform’s financial constraints and management guidelines, a 10% adjustment threshold above and below 25% (i.e., 15 to 35% commission range) is set.

In mapping SPES to commission, taking two decimals into account, we first match the possible SPES (i.e., varying from 1.00 to 5.00, i.e., 400 values) with possible commission (varying from 15.00 to 35.00%, i.e., 2,000 values). Given that there are five times more values in commission compared to SPES, we consider every 0.01 increase in SPES as 0.05% reduction from 35% in platform’s commission (e.g., for \({{\text{SPES}}}_{{\text{it}}}\)=1,3, and 5, commissions are set as 0.35, 0.25, and 0.15, respectively, operationalized as [35-(\({{\text{SPES}}}_{{\text{it}}}\)-1)\(*\) 5]). This setting ensures the platform’s average commission in the treatment condition to remain the comparable to the fixed commission (i.e., 25% commission on an average).

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Doğan, O.B., Kumar, V. & Lahiri, A. Platform-level consequences of performance-based commission for service providers: Evidence from ridesharing. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-024-01005-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-024-01005-0