Abstract

We present an integrative review of existing marketing research on mobile apps, clarifying and expanding what is known around how apps shape customer experiences and value across iterative customer journeys, leading to the attainment of competitive advantage, via apps (in instances of apps attached to an existing brand) and for apps (when the app is the brand). To synthetize relevant knowledge, we integrate different conceptual bases into a unified framework, which simplifies the results of an in-depth bibliographic analysis of 471 studies. The synthesis advances marketing research by combining customer experience, customer journey, value creation and co-creation, digital customer orientation, market orientation, and competitive advantage. This integration of knowledge also furthers scientific marketing research on apps, facilitating future developments on the topic and promoting expertise exchange between academia and industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mobile apps, or apps in short, have been defined as the ultimate marketing vehicle (Watson, McCarthy and Rowley 2013) and a staple promotional tactic (Rohm, Gao, Sultan and Pagani 2012) to attract business ‘on the go’ (Fang 2019). They yield great potential for customer engagement due to specific characteristics (e.g., vividness, novelty and built-in features, see Kim, Lin and Sung 2013), supporting one-to-one and one-to-many interactions (Watson et al. 2013) and facilitating exchanges without time or location-based restrictions (Alnawas and Aburub 2016). In essence, apps translate communication efforts into interactive customer experiences heightening cognitive, emotional and behavioral responses (Kim and Yu 2016). For example, apps support value-generating activities such as making purchases and accessing information (Natarajan, Balasubramanian and Kasilingam 2017). Accordingly, apps offer firms multiple opportunities to achieve marketing objectives, influencing and shaping the customer journey (Wang, Kim and Malthouse 2016a). Overall, apps also allow firms to realize a digital customer orientation and to attain competitive advantages through the provision of superior customer experiences (Kopalle, Kumar and Subramaniam 2020).

Over the last decade, the popularity of apps continued to increase (currently, there are more than 2.87 million apps available, Buildfire 2021) and, although apps’ growth has gradually slowed down, they remain at the heart of digital marketing strategies, impacting economies worldwide (Arora, Hofstede and Mahajan 2017). For instance, in the US, apps drive about 60% of digital media consumption (Fang 2019) and 90% of the top 100 global brands offer one or more apps (Tseng and Lee 2018). Apps also generate significant economic results thanks to attaining prolonged media exposure and consumer spending. For example, the TikTok app generates over one billion video views every day (Influencer Marketing Hub 2018; Iqbal 2019) and has attracted $50 million in consumer spending last year, on top of advertising revenues (Williams 2020). The global health and financial crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic further illustrates the pivotal role apps play in facilitating business survival and reigniting customer experiences—see the instance of the Zoom app, which generated $2.6 billion revenue in 2020 (Sensortower 2020).

An increase in academic research on apps has matched their growth in popularity. Marketing is no exception to this trend; however, it lacks a state-of-the-art integrative review, which hinders the advancement of this field of inquiry. Integrative reviews offer new insights as a result of synthesis and critique, and are crucial for new knowledge generation (Elsbach and van Knippenberg 2020). Importantly, integrative reviews form the basis for justification or validation of established knowledge (MacInnis 2011); they also “identify new ways of conceiving a given field or phenomenon” (Post, Sarala, Gattrell and Prescott 2020, p.354). Moreover, in addition to their substantiative theoretical contribution, integrative reviews typically facilitate the exchange of knowledge between academia and industry. Based on this reasoning, the present study has two research objectives. The first objective (RO1) is to synthesize existing research on apps to sharpen scholarly understanding of their key role in marketing and customer experiences. To do so, we review established findings through the theoretical lens of the customer journey (Lemon and Verhoef 2016), which we modify and extend to establish conceptual links with digital customer orientation, market orientation and competitive advantage. As illustrated, the factor that connects these concepts and explicates apps’ relevance to marketing is value (including value co-creation). The second objective (RO2) involves offering a series of directions for future research based on priority knowledge gaps. The ultimate goal is to define future research paths for marketing scholars, while promoting knowledge and data exchange between academia and practice.

Comprehensively, this study constitutes the most extensive attempt in the marketing literature to integrate and review the full breadth of publications on apps and significantly differs from existing reviews (e.g., Ström, Vendel and Bredican 2014; Nysveen, Pedersen and Skard 2015). In particular, we synthesize 471 bibliometric sources, maintaining a clearer delineation between mobile technologies in general vs. apps. Our review also covers all types of apps and includes a unified conceptual framework—two further limitations of prior attempts (e.g., Tyrväinen and Karjaluato 2019; Mondal and Chakrabarti 2019).

Review approach

In line with past studies (e.g., Groenewald 2004; Mkono 2013), we used a semi-inductive approach to integrate and review marketing knowledge on apps. Specifically, as appropriate when reviewing fields that are not yet stabilized (Roma and Ragaglia 2016), we first conducted a bibliometric analysis to identify relevant sources, mapping the overall knowledge field via quantitative assessment of authors, references and citations (Culnan et al. 1990). We followed the same procedure as Samiee and Chabowski (2012), which begins with identifying keywords. In this regard, we drew upon extant literature on apps (e.g., Mondal and Chakrabarti 2019) to collate sources, which contained in the title, abstract or keywords any of the following terms: mobile application(s), mobile app(s), mobile phone application(s), mobile phone app(s), smartphone application(s), smartphone app(s), and apps(s). This selection aligns with past studies (e.g., Radler 2018) and reflects synonyms of apps used in real life. We also narrowed down the bibliometric data to sources with a clear marketing focus by screening for terms such as marketing, consumer or customer in the title, abstract or keywords. At times, this approach resulted in the inclusion of sources outside the confines of marketing research (e.g., technology and information system and/or management). Following a similar protocol to others (e.g., Wang, Zhao and Wang 2015; Mondal and Chakrabarti 2019), we located all sources from the Scopus database, concentrating on articles published in the last two decades—a timeframe, which captures seminal studies and more recent research. The second step of the review process involved screening all bibliometric sources to identify recurring themes and established findings. Following recent guidelines for developing insightful reviews (Hulland and Houston 2020), this intuitive review step also entailed locating and examining additional bibliometric sources not included in the initial data frame. The Web Appendix describes all sources examined (471) and a full-length bibliography.

Superordinate theoretical lens

To present the outcomes of our integrative review, we modify and expand the scope of the customer journey by Lemon and Verhoef (2016). This framework is applicable to different consumption contexts and simplifies the complexity resulting from seemingly disconnected theoretical bases. Moreover, it serves as a useful basis to understand and manage customer experiences. Customer experiences combine cognitive, emotional, behavioral, sensory and social aspects related to distinct consumption stages and touchpoints (see Verhoef, Lemon, Parasuraman, Roggeveen, Tsiros and Schlesinger 2009; Becker and Jaakkola 2020). In relation to apps, McLean, Al-Nabhani and Wilson (2018) highlight that the experiential (or journey) factor has been neglected thus far. This knowledge void is surprising, since apps are considered catalysts of ‘new’ customer experiences due to being a unique source of customer value. Nonetheless, apps call for critical modifications of Lemon and Verhoef’s (2016) framework, as follows.

First, we synthesize research across three journey stages: pre-adoption, adoption and post-adoption.Footnote 1 The pre-adoption stage concerns customer experiences and decision-making before app adoption, which shape consumer predispositions toward the app. In more detail, this stage captures the theoretical links between positive consumer attitudes, individual characteristics and the intention to download, adopt or use the app; it also includes firm/brand-initiated strategies to enhance consumer predispositions. The adoption stage includes customer experiences inherent to the continuation of the consumer decision-making process past initial predispositions, which signal app download and use. Experiences arise from firm/brand-initiated strategies and associated consumer reactions; they also originate from consumer characteristics likely to impact the choice of an app. Moreover, this stage includes activities that signify adoption such as using the app (e.g., mobile shopping). The post-adoption stage involves all customer experiences following adoption and resulting from ongoing app usage such as stickiness—i.e., the intention to continue using the app and frequency of app usage (Racherla, Furner and Babb 2012); and engagement (e.g., Kim et al. 2013; Wu 2015; Fang 2017)—i.e., “a customer’s voluntary resource contribution to a firm’s marketing function, going beyond financial patronage” (Harmeling, Moffett, Arnold and Carlson 2017, p.312). This final stage also includes relevant outcomes for the app and for the brand behind the app such as brand loyalty and customer satisfaction.

In line with Lemon and Verhoef’s (2016) assumptions, we contend the distinction between the three customer journey stages to be conceptually and practically fluid. Specifically, the adoption and post-adoption stages are blurred by a seamless feedback loop, since the decision-making process underpinning app adoption is likely to start from pre-adoption predispositions, and to be re-lived during activities that signify adoption whilst also shaping crucial post-adoption outcomes. However, for practical purposes, we distinguished bibliometric sources related to each stage by focusing on the focal concept or key dependent variable discussed in each source. For instance, we considered studies on intentions to adopt the app for pre-adoption; studies on app usage were examined for the adoption stage; and studies on stickiness and engagement were reviewed in relation to post-adoption.

A second modification of the original framework concerns the touchpoints. In more detail, we integrate brand-owned and partner-owned touchpoints, which are designed, managed and controlled by the firm and/or other partners (e.g., developers and app stores) due to the unique business model of app stores (Jung, Baek and Lee 2012); and consumer-owned and social touchpoints, which are out of the firm’s direct control, highlighting the extraordinary level of direct consumer involvement with apps through seamless feedback mechanisms—e.g., through customer ratings and reviews. Based on apps’ ubiquitous nature (Tojib and Tsarenko 2012), we also consider these touchpoints as “always-on” points of interaction with a pervasive impact across all stages. For instance, taking the app’s marketing mix as an example (a key brand and partner-owned touchpoint), we assume it to impact consumer initial predispositions toward the app (pre-adoption); app usage (adoption) and consumer responses to the app (post-adoption).

Finally, to further enhance the theoretical and managerial contributions made, we expand the framework’s scope by linking it to customer orientation and competitive advantage via the broad notion of customer value. Kopalle et al. (2020) clarify that any brand or firm can harvest market opportunities by embracing a digital customer orientation. Digital customer orientation occurs “when the customization and enrichment of the experience delivered by a firm is in real-time and based on the in-use feedback from customers” (Kopalle et al. p. 115). This definition requires a platform for information sharing, real-time insights and context-driven value creation and co-creation. Apps are ideal platforms, as consumers can easily act as integrators of value and resources throughout the customer journey. For example, the business model of app stores hinges on user feedback and information exchange across the supply chain, extending the scope of apps to a broad service delivery network (Tax, McCutcheon and Wilkinson 2013). Apps are also viewed as dynamic packages of service provision (see Piccoli, Brohman, Watson and Parasuraman 2009), or ‘bundles’ of stimuli, functionalities and experiences that facilitate value creation and co-creation inherent to the appscape (Kumar, Purani and Viswanathan 2018; Lee 2018b). Finally, apps are a pivotal source of hyper-contextualized consumer insights, which can be turned into market intelligence (Tong et al. 2020). By making consumer insights and market intelligence part of inter-functional coordination and strategic implementation (Narver and Slater 1990; Deshpandé, Farley and Webster 1993; Lafferty and Hult 2001), firms can consistently deliver superior customer value, attaining market orientation and competitive advantages via apps (when the app is linked to an existing brand) and for apps (when the app is the brand) .

Pre-adoption stage

Empirical research on the pre-adoption stage is abundant and focuses on two aspects that initiate the consumer decision-making process shaping consumer predispositions toward the app, driving the intention to download and/or adopt an app over other alternatives: the technological features and benefits consumers seek; and specific individual consumer characteristics. In contrast, research exploring different strategies for encouraging apps adoption is scarce. Table 1 summarizes existing theoretical approaches inherent to this stage, together with future research themes and examples of priority research questions.

Initiation of the consumer decision-making process

Technological features and benefits sought

Extant research extensively documents technological features and benefits that consumers seek in apps, using the Technology Adoption Model (TAM) (Davis, Bagozzi and Warshaw 1989) and modifications of it, including conceptual models that combine technology adoption with Diffusion of Innovation Theory (Rogers 2005) and Uses and Gratification (U&G) theory (Mcguire 1974, Eighmey and McCord 1998). In particular, past research consistently highlights the following key pre-adoption drivers. First, incentives of technology adoption such as usefulness, ease of use and enjoyment—all confirmed to enhance consumer positive attitudes and/or evaluations of an app, thus underpinning the intention to download and/or adopt the app (Bruner and Kumar 2005; Hong and Tam 2006; Karaiskos, Drossos, Tsiaousis, Giaglis and Fouskas 2012; Ko, Kim and Lee 2009; Maity 2010; Wang and Li 2012; Kim, Yoon and Han 2016b; Li 2018; Stocchi, Michaelidou and Micevski 2019). Second, numerous studies stress the importance of value perceptions (Peng, Chen and Wen 2014; Zhu, So and Hudson 2017; Zolkepli, Mukhiar and Tan 2020), especially perceptions of convenience (Kim, Park and Oh 2008; Kang, Mun and Johnson 2015); novelty, accuracy and precision (Ho 2012); locatability (i.e., identifiability in space and time); and, more broadly, apps’ quality (Noh and Lee 2016). Studies also highlight apps’ potential to create positive consumer predispositions via personalization (Tan and Chou 2008; Wang and Li 2012; Watson et al. 2013; Li 2018); pleasant aesthetics (Stocchi et al. 2019; Kumar et al. 2018; Lee and Kim 2019); and the perceived monetary value (Hong and Tam 2006; Kim et al. 2008; Venkatesh, Thong and Xu 2012), which often counterbalances effort expectancy (Kang et al. 2015). Third, past research often explains the pre-adoption decision-making process via concentrating on medium characteristics such as apps’ compatibility, controllability, connectivity and service availability (Kim et al. 2008; Ko et al. 2009; Lu, Yang, Chau and Cao 2011; Mallat, Rossi, Tuunainen and Öörni 2009; Tan and Chou 2008; Wu and Wang 2005); and medium richness (Lee, Cheung and Chen 2007). Similarly, other research focuses on consumer’s positive attitudes resulting evaluations of the technology provider such as reputation (Chandra, Srivastava and Theng 2010) and communicativeness (Khalifa, Cheng and Shen 2012); or network factors including synergies with other channels (Kim et al. 2008) and app popularity (Picoto, Duarte and Pinto 2019).

The same technological features and benefits discussed so far are recurrently mentioned within industry reports explaining how to attract app users (e.g., IBM Cloud Education 2020; Babich 2017; Payne 2021). Nonetheless, there is a limited understanding of which combinations of technological features and benefits sought most impact the intention to download and/or adopt an app. Such insights could originate from experimental studies shedding light on how consumers choose an app over alternatives. There is also scope for longitudinal analyses of which technological features most impact app market performance.

Individual characteristics

Several marketing studies catalogue individual consumer characteristics that drive the intention to adopt an app, stemming from a combination of personality traits theory (McCrae, Costa 1987; John and Srivastava 1999), consumer involvement theory (Richins and Bloch 1986; Mittal 1989), and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Ajzen 1991; Azjen 1980). Combining these theories, it is possible to identify the following recurring drivers. First, we find studies highlighting the relevance of generic factors likely to influence consumer pre-dispositions at the early stages of any decision-making process, such as consumer involvement (Taylor and Levin 2014), inertia (Wang, Ou and Chen 2019), consumer experience (Lee and Kim 2019; Kim et al. 2013) and past behavior (Atkinson 2013; Ho 2012; Kang et al. 2015). We also find research highlighting the impact of behavioral control and self-efficacy (Kleijnen, de Ruyter and Wetzels 2007; Maity 2010; Sripalawat, Thongmak and Ngramyarn 2011; Wang, Lin and Luarn 2006), social norm (Hong and Tam 2006; Karaiskos et al. 2012; Lu et al. 2007, 2008) and motives (Bruner and Kumar 2005). Second, we find research remarking the importance of key individual differences, such as consumer demographics (Yang 2005; Carter and Yeo 2016; Veríssimo 2018; Hur, Lee and Choo 2017), lifestyle (Kim and Lee 2018), personality (Xu, Peak and Prybutok 2015; Frey, Xu and Ilic 2017) and individual traits like innovativeness (Lu, Wang and Yu 2007; Liu, Yu and Wang 2008; Hur et al. 2017; Karjaluoto, Shaikh, Saarijärvi and Saraniemi 2019), optimism (Kumar and Mukherjee 2013) and mavenism (Atkinson 2013).

Despite the great emphasis on these aspects, there is a scope for new studies examining their implications for apps avoidance (i.e., not wanting to adopt an app) and apps resistance (i.e., opposing or postponing app adoption). Furthermore, it is crucial to investigate apps’ re-adoption, since many apps are downloaded but abandoned shortly afterwards (Baek and Yoo 2018). Such new research endeavors can shed further light on app abandonment caused by sampling (Roggeveen, Grewal and Schweiger 2020), meeting industry needs. In fact, industry reports lament that only one in four users use apps one day after the download, and within three months after download over 70% of the app users have churned (Kim 2019).

Route to introduction (strategies for encouraging app adoption)

Existing research exploring strategies that encourage app adoption primarily draws from industry trends, as opposed to empirical evidence or conceptual work (see Zhao and Balagué 2015). Hence, the need for new frameworks outlining and evaluating strategies for apps’ introduction is pressing. In particular, there is scope for empirical studies assessing the effectiveness of alternative market introduction strategies for different app types. For example, future research on pre-adoption of apps linked to existing brands could compare apps against other brand touchpoints (see also Peng et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2016a). Similarly, future research on pre-adoption of standalone apps could concentrate on appraising the implications of the app’s marketing mix (discussed later on in this integrative review).

Adoption stage

The adoption stage of the customer journey for apps and via apps covers the continuation of the consumer decision-making process until app adoption, including any activities that signify adoption—e.g., behaviors resulting from using the app such as mobile shopping and in-app purchases. Table 2 combines theoretical approaches used to explore these aspects; it also lists key themes for future research, alongside examples of unanswered questions.

Continuation of the consumer decision-making process

Past studies focus on technological features and benefits sought, or on individual consumer characteristics also in relation to the pre-adoption stage. In relation to the first aspect, many scholars confirm the importance of the same pre-adoption drivers (e.g., ease of use, usefulness and enjoyment), either directly or via attitudes and/or intentions (see Gao, Rohm, Sultan and Pagani 2013; Huang, Lin and Chuang 2007; Koenig-Lewis, Marquet, Palmer and Zhao 2015; Veríssimo 2018; Stocchi, Pourazad and Michaelidou 2020a). Past research also highlights new drivers such as mobility value (i.e., the combination of convenience, expediency and immediacy, see Huang et al. 2007) and ubiquity (i.e., the possibility to access products and services “anytime, anywhere”, see Tojib and Tsarenko 2012). Other drivers of app adoption and/or use include trust (Chong, Chan and Ooi 2012), device compatibility (Wu and Wang 2005), app price (Malhotra and Malhotra 2009), provider reputation (Chandra et al. 2010), consumer experiential learning (Grant and O’Donohoe 2007) and perceived media flow (Wu and Ye 2013). In terms of individual characteristics, extant studies confirm the same range of factors as in pre-adoption (Mort and Drennan 2007; Bhave, Jain and Roy 2013; Byun, Chiu and Bae 2018; Taylor, Voelker and Pentina 2011; Yang 2013; Kang et al. 2015). Research also highlights the importance of consumer motives (Jin and Villegas 2008), social influence (Chong et al. 2012), attachment with the device (Rohm, Gao, Sultan and Pagani 2012) and self-to-app connection (Newman, Wachter and White 2018). Additionally, some studies reveal further important individual level factors such as consumer innovativeness (Lewis et al. 2015), consumer knowledge (Koenig-Lewis et al. 2015), personality (Pentina, Zhang, Bata and Chen 2016; Fang 2017) and a sense of self (Scholz and Duffy 2018). Moreover, several studies uncover new drivers such as escapism (Grant and O’Donohoe 2007), playfulness and drive stimulation (Mahatanankoon, Wen and Lim 2005). There are also studies highlighting the importance of usage values (Liu, Zhao and Li 2017) and advantages (Zolkepli et al. 2020; Newman, Wachter and White 2018; Arya, Sethi and Paul 2019), including information needs (Alavi and Ahuja 2016) and usage preferences (Doub, Levin, Heath and LeVangie (2018); Cheng, Fang, Hong and Yang 2017) such as browsing (Kim, Kim, Choi and Trivedi 2017).

The range of theoretical approaches underpinning the research mentioned so far is broad. For example, we find theories not explored for pre-adoption like experiential learning theory (Kolb 1984), media flow theory (Wu and Ye 2013), motivation theory (Herzberg, Mausner and Bloch-Snyderman 1959) and the self-concept (Sirgy 1982). Nonetheless, a common aspect connecting these seemingly disparate theoretical bases is the notion of value. Specifically, there is an emphasis on different types of consumer values (e.g., utilitarian and hedonic) assumed to encourage the shift from the intention to adopt an app to actual adoption and/or use. Although this assumption is plausible and empirically sound, there is scope for new investigations outlining the consumer decision-making process resulting in app adoption and/or use in greater detail. For instance, scholars could adapt conceptual frameworks explicating how consumers evaluate brands for choice (e.g., Keller 1993).

Behaviors that signal adoption

The industry distinguishes 33 app categories in the Google Play store and 24 categories in the Apple’s App Store, out of which popular app categories (i.e., categories with an uptake greater than 3%) include apps linked to retailers, games and lifestyle apps (Think Mobile 2021). Considering these popular app categories, two key behaviors signaling adoption echo the focus of extant marketing studies: mobile shopping via apps and in-app purchasing.

Mobile shopping

Past research clarifies the factors that encourage purchasing via the app and the intention to purchase the brand powering the app (when the app is linked to an existing offline or online brand). In terms of factors that encourage purchases via the app vs. other channels, extant studies identify the importance of positive customer experiences, especially the speed of transactions, security and user-friendliness that apps can provide (Buellingen and Woerter 2004; Figge 2014); consumer participation, flexibility and technology quality (Mäki and Kokko 2017; Dacko 2017); location awareness and interactivity (Wang et al. 2016a); and access to information and promotions (Magrath and McCormick 2013). Extant research also discusses the relevance of the customer’s overall interest in the app (Taylor and Levin 2014) and specific apps’ attributes (e.g., ease of use and connection with the self) as drivers of the intention to purchase via the app over the physical store (Newman et al. 2018), often due to heightening buying impulses (Wu and Ye 2013; Chadha, Alavi and Ahuja 2017). Finally, past studies highlight two factors that underpin the intention to purchase the brand powering the app: the provision of holistic brand experiences (Wang and Li 2012; Kim and Yu 2016; Chen 2017; Fang 2017) and and app usability (i.e., “the extent to which a mobile app can be used to achieve a specified task effectively during brand-consumer interactions” Baek and Yoo 2018, p. 72).

Considering the above, more research is needed to clarify how purchases via apps occur, including any facilitating or inhibiting factors, as these strongly correspond with industry priorities. Indeed, industry experts call for more insights on how personalized content and push notifications might encourage purchasing via the app (Anblicks 2017; Tariq 2020). Such future research extensions could also reinforce rather scattered theoretical bases, which primarily include expectancy theory (Vroom 1964), motivation theory (Herzberg et al. 1959), Uses and Gratifications (U&G) theory (Mcguire 1974) and customer satisfaction theory (Churchill Jr. and Surprenant 1982). Finally, in terms of apps attached to existing brands, future research could evaluate the impact on brand sales and/or other brand performance indicators. For example, future studies could consider the effects of apps as a tool to enhance a brand’s availability in consumer’s memory, ultimately impacting brand purchase intentions (see Sharp 2010; Romaniuk and Sharp 2016).

In-app purchasing

Research predicting in-app purchases highlights, as key drivers, perceived app value (i.e., quality, value for money, social and emotional value—see Hsu and Lin 2015; and Hsiao and Chen 2016) and features of the app that motivate app use (Stocchi, Michaelidou, Pourazad and Micevski 2018; Stocchi et al. 2019). Extant studies also remark the importance of personality traits such as bargain proneness, frugality and extraversion (Dinsmore, Swani and Dugan 2017), and price sensitivity, which Natarajan et al. (2017) found to alter perceptions of risk, usefulness, enjoyment and personal innovativeness, via customer satisfaction (see also Kübler, Pauwels, Yildrim and Fandrich 2018). Since the conceptual focus and scope of extant studies is somewhat confined, future research could expand the theoretical bases used by considering established patterns and regularities in buying behavior (see the work of Sharp 2010; and Romaniuk and Sharp 2016).

Post-adoption stage

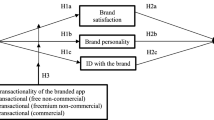

The post-adoption stage concerns two aspects: ongoing or continued app usage, explored through the notions of stickiness and engagement; and outcomes of app adoption for the app itself and for the brand behind the app, as applicable. Table 3 maps extant theoretical approaches vs. outstanding research themes and priorities linked to these aspects, with examples of research questions yet to be explored (Fig. 1).

Ongoing (continued) app usage

App stickiness

Racherla, Furner and Babb (2012) and Furner, Racherla and Babb (2014) link app stickiness to telepresence, which comprises two dimensions: vividness and interactivity. Vividness influences a medium’s ability to induce a sense of presence resulting from its breadth (sensory dimensions and cues) and depth (quality of presentation). Interactivity is the extent to which users can modify the medium’s form and content in real-time. Similarly, Chang (2015) and Xu et al. (2015) explore loyalty towards apps focusing on perceived value and customer satisfaction. Other studies concentrate on the continued intention to use an app, highlighting the importance of consumer perceptions of apps’ features (Kim, Baek, Kim and Yoo 2016), especially design, functionality and social features (Tarute, Nikou and Gatautis 2017a). For example, Tseng and Lee (2018) confirm that improving loyalty towards branded apps can be achieved through an affective path (i.e., bolstering functional, experiential, symbolic and monetary benefits) and a utilitarian path (i.e., emphasizing system and information quality). Similarly, Alalwan (2020) links performance expectancy and hedonic motivation to the continued intention to use apps.

The above studies draw upon different theoretical bases, albeit consistently highlighting the importance of value perceptions resulting from customer experiences. Nonetheless, past research bears two recurring issues: inconsistent conceptualizations and measurements, and the conflation with other prominent notions such as app engagement. These two issues could be turned into future research providing a unified definition and measure of app stickiness. Future research could also explore the outcomes of app stickiness, clarifying if it can improve apps’ market performance and survival chances. Lastly, there is scope for longitudinal studies examining fluctuations in app stickiness, especially pre and post app modifications. Notably, these future endeavors all yield significant synergies with current industry practices and trends (see App Radar 2019, The Manifest 2018).

App engagement

According to Kim et al. (2013) and Wang et al. (2016b), app engagement can be understood as the sum of motivational experiences (see also Calder and Malthouse 2008) that connect the consumer to the app. Similarly, Dovaliene, Masiulyte and Piligrimiene (2015) and Dovaliene, Piligrimiene and Masiulyte (2016) theorize consumer engagement with apps as a mixture of cognitive, emotional and behavioral aspects (see also Jain and Viswanathan 2015), while Noh and Lee (2016) link consumer intention to engage with apps to perceptions of quality. Adapting Calder, Malthouse and Schaedel’s (2009) measure of media engagement, Wu (2015) confirms that effort expectancy, performance expectancy, social influence and consumer-brand identification underpin consumer engagement, which then drives the intention to continue app usage. In contrast, Kim and Baek (2018) use Kilger and Romer’s (2007) measure of media engagement to evaluate branded apps engagement. This approach closely aligns with Eigenraam, Eelen, van Lin, and Verlegh’s (2018) definition of digital engagement, which captures consumers’ tendency to conduct various tasks beyond usage of branded services, displaying behaviors that signal engagement. In a similar vein, Tarute, Nikou and Gatatuis (2017a) modify Hollebeek, Glynn and Brodie’s (2014) work and contend that engagement with apps originates from the intensity of individual participation and motivation (see also Vivek, Beatty and Morgan 2012). Stocchi et al. (2018) explore consumer motives for engaging with apps, while Fang, Zhao, Wen and Wang (2017) consider branded apps’ characteristics that underpin psychological engagement (i.e., a highly subjective state characterized by deep focus, concentration and absorption), assumed to drive behavioral engagement (i.e., the consumer intention to engage with the branded app). Past studies also analyze consumer engagement behaviors (i.e., manifestations towards the brand or the firm beyond purchase that strengthen the consumer-brand relationship and generate value, see van Doorn, Lemon, Mittal, Nass, Pick, Pirner and Verhoef 2010). For example, Viswanathan, Hollebeek, Malthouse, Maslowska, Kim and Xie (2017) infer app engagement from the behavior changes of customers enrolled in the loyalty program. Gill, Sridhar and Grewal (2017) return similar findings for B2B apps. Lee (2018b) and van Heerde, Dinner and Neslin (2019) highlight that consumer engagement behaviors have a strong bearing on brand loyalty. Finally, Chen (2017) and Fang (2017) predict engagement with the brand powering the app.

In essence, existing research on apps’ engagement presents contrasting assumptions and conceptualizations, which place emphasis on different cognitive and psychological aspects resulting from an evaluation of the benefits (and thus values) that apps offer. Therefore, there is scope for a unified definition and measurement of app engagement combining diverging theoretical perspectives such as motivation theory (Herzberg et al. 1959), flow theory (Wu and Ye 2013), transportation theory (Green and Brock 2000), media engagement theory (Kilger and Romer 2007, Calder and Malthouse 2008) and the Customer, Value, Satisfaction and Loyalty (VSL) framework (Lam, Shankar, Erramilli and Murthy 2004; Yang and Peterson 2004). Meeting recurring industry priorities (Beard 2020; Marchick 2014; Facebook 2021), future research could aso explore disengagement—i.e., when consumers de-escalate the frequency of app usage (see also Wang et al. 2016c), as well as the link between app engagement and other apps performance indicators such as downloads.

Outcomes for the app

Extant research exploring the outcomes of app adoption for the app itself concentrates on two key aspects: the willingness to spread word-of-mouth (WOM) about the app and the willingness to re-purchase via the app. For example, Furner, Racherla et al. (2014) attribute consumer willingness to spread positive WOM about mobile apps to the app’s stickiness. In a similar vein, Baek and Yoo (2018) link branded apps’ continued usage intention to branded apps’ referral intentions. Embracing a different conceptual angle, Xu et al. (2015) highlight the link between perceptions of app value, satisfaction with the app, loyalty towards the app and WOM about the app, which the authors consider to be a form of experiential computing. Other studies attribute the consumer’s inclination to recommend apps to the level of app loyalty resulting from perceptions of value (Chang 2015) or service quality (Chopdar and Sivakumar 2018). On occasion, past research explores specific characteristics of branded apps likely to entice WOM such as usefulness (Kim et al. 2016), ease of use and personal connection (Newman et al. 2018), and utilitarian and hedonic benefits (Stocchi et al. 2018). In terms of the willingness to re-purchase via the app and other mobile shopping changes, Kim et al. (2015), Wang, Xiang, Law and Ki (2016a) and Gill et al. (2017) demonstrate that using an app increases spending over time. In light of these findings, research on the outcomes of app adoption for the app reveals substantial scope for expansion. In particular, future research could explore the underlying mechanisms linking perceptions of value (especially value in use), satisfaction with the app and outcomes beyond the standard chain of effects leading to WOM and/or other forms of loyalty toward the app.

Outcomes for the brand behind the app

Research exploring the outcomes for the brand behind the app covers a wide range of conceptual bases, including persuasion theory (Petty and Cacioppo 1986), involvement theory (Richins and Bloch 1986; Mittal 1989), self-congruence theory (Aaker 1999; Sirgy, Lee, Johar and Tidwell 2008) and consumer-brand relationship theory (Fournier 1998). Nonetheless, given the theoretical and managerial relevance of these aspects, there is ample scope for new marketing knowledge, as follows.

Brand loyalty

Lin and Wang (2006) theorize brand loyalty as the outcome of perceived value, customer satisfaction, trust and habits inherent to m-commerce apps. Similarly, Kim and Yu (2016) evaluate the extent to which branded apps can drive brand loyalty through the provision of a continuous brand experience, which they defined as “sensation, feelings, cognition and behavioral responses evoked by brand-related stimuli that are all a part of a brand’s design, identity, packaging, communication, and environment” (p.52). Embracing a slightly different focus, Baek and Yoo (2018) focus on branded apps’ usability, seen as conceptually woven into the user experience. Therefore, building upon these past studies and their implications, future research could focus on the psychological mechanisms that increment brand loyalty via app usage. For example, keeping in mind the established conventions of how brands grow (Sharp 2010; Romaniuk and Sharp 2016), there is scope for investigating app characteristics likely to enhance brand loyalty for different customer segments. There is also scope for research exploring the reverse effect, i.e. studies evaluating the impact of brand loyalty on app performance.

Willingness to spread WOM about the brand

Kim and Yu (2016) attribute consumer’s willingness to spread positive WOM about the brand powering an app to the holistic brand experience resulting from using the app. Similarly, Sarkar, Sarkar, Sreejesh and Anusree (2018) link positive WOM about retailers to the use of related apps. To revamp scholarly and managerial attention around this theme, future studies could establish a connection with the latest online WOM research (e.g., Ismagilova, Slade, Rana and Dwivedi 2019; Sanchez, Abril and Haenlein 2020; Rosario, de Valck and Sotgiu 2020). Such studies could also consider instances whereby buzz about the brand might impact app performance.

Persuasion

Wang et al. (2016a) present a series of theoretical reflections concerning the persuasive nature of branded apps, highlighting apps’ ability to trigger frequent context-based brand recall. Bellman, Potter, Treleaven-Hassard, Robinson and Varan (2011) add that branded apps can persuade consumers by increasing interest in the brand powering the app (purchase intention) and in the product category (product involvement). At the same time, Ahmed, Beard and Yoon (2016) remark that apps’ persuasive potential originates from vividness, novelty, and multi-platforming opportunities (see also Kim et al. 2013). Similarly, Alnawas and Aburub (2016) and Seitz and Aldebasi (2016) attribute apps’ persuasiveness to the benefits offered, which can be cognitive (information acquisition), social integrative (connecting with others), personal integrative (self-value bolstering) and hedonic (e.g., escapism). More recently, Lee (2018a) examines the dual route to persuasion for apps, including argument quality (central route) and source credibility (peripheral route), while van Noort and van Reijmersdal (2019) evaluate cognitive and affective brand responses to apps.

In line with the above, apps’ persuasive power is widely established, a trend that is also apparent in mobile advertising trends (via apps and in-apps), which continue to overtake desktop advertising (eMarketer 2019). Nonetheless, there is scope for new knowledge evaluating the outcomes of advertising via apps beyond attitude change and brand purchase intentions (see Ahmed et al. 2016), explicitly appraising apps’ effects on brand recall and brand recognition (see Ström et al. 2014; van Noort and Reijmersdal 2019). There is also scope for replications and extensions of Bellman et al.’s (2011) seminal work, bringing neuroscience into marketing research on apps. For example, future research could determine the most persuasive app features for different consumer segments. It is equally paramount to consider the effects of deploying apps compared to other advertising channels. Such comparisons could evaluate synergies between apps and other digital media (especially social media), guiding firms in advertising platform choices whilst avoiding unduly media duplication. Future studies could also explore the impact of brand advertising on app performance. These future investigations are relevant to the industry, as apps are considered superior advertising channels than websites (Deshdeep 2021).

Customer satisfaction

Lin and Wang (2006) attribute customer satisfaction to perceptions of app value and consumer trust. Subsequent studies often refer to these original findings, albeit returning either too simplistic (Lee, Tsao and Chang 2015) or too intricate research frameworks (Xu et al. 2015), or frameworks not focused on the prediction of customer satisfaction (Natarajan et al. 2017). Other studies concentrate on utilitarian and hedonic benefits that apps offer vs. non-monetary sacrifices such as privacy surrender (Alnawas and Aburub 2016). In contrast, Alalwan (2020) considers online reviews, performance expectancy, hedonic motivation and price value. Among studies exploring perceptions of value and customer satisfaction, Chang (2015) looks at emotional and social values, app quality and value for money. Likewise, Rezaei and Valaei (2017) find that experiential values (i.e., service excellence, customer return on investment, aesthetics and playfulness) positively influence satisfaction. In contrast, Iyer, Davari and Mukherjee (2018) find that both functional and hedonic values positively influence consumer satisfaction from the branded app, while social values have a negative impact (see also Karjaluoto et al. 2019).

Considering the above and, more generally, the pivotal role of perceptions of value seen in extant research on pre-adoption and adoption, there is limited ground for additional endeavors exploring these aspects. However, there is a need for research clarifying how to measure service quality for apps and evaluating the differences with other non-digital sources of customer satisfaction. In fact, only two studies have explored these aspects, proposing inconsistent models. Specifically, Demir and Aydinli (2016) outline seven dimensions of service quality for instant messaging apps (communication, data transferring, distinctive features aesthetics, security, feedback, and networking), while Trivedi and Trivedi (2018) explore the antecedents of satisfaction with fashion apps adding other perceived quality dimensions. There is also scope for new research exploring the on-going effects of attaining brand engagement via apps, expanding the exploratory work by Chen (2017) on brands active on WeChat. Finally, it is worth exploring instances whereby customer satisfaction with the brand and brand engagement might influence app performance.

Emotional response toward the brand

When interacting with mobile technologies, users often experience strong emotional responses, which can result in the willingness to act without thinking (McRae, Carrabis, Carrabis and Hamel 2013). Indeed, van Noort and van Reijmersdal (2019) show that entertaining apps heighten affective brand responses and, according to Arya et al. (2019), consumers might become brand vocals. Moreover, apps can trigger emotional connections between the consumer and the brand, on the basis of self-congruence (Iyer et al. 2018; Kim and Baek 2018; Yang 2016) or self-app connection, arising from personalized consumption experiences that turn apps into digital manifestations of one’s preferences, desires and needs (Newman et al. 2018). Apps can also lead to brand attachment (i.e., an emotional bond between the consumer and the brand); brand identification (i.e., overlap between the consumer and the brand, see Peng et al. 2014); brand affect (i.e., deep emotions towards the brand, see Sarkar et al. 2018); brand love (i.e., a romantic connection between the brand and the consumer, see Baena 2016); and brand warmth (i.e., the belief that a brand is friendly, trustworthy and truthful, see Fang 2019). Building upon these findings, there is an opportunity to examine the cognitive and affective brand responses that result from using different types of apps (see also van Noort and van Reijmersdal 2019) and how these might impact app performance. Such studies could return relevant insights useful to the identification of strategies for market survival and attaining a competitive advantage for apps through building strong connections with consumers.

“Always on” points of interaction

Research linked to brand and partner-owned, and consumer-owned and social “always on” points of interaction is nascent, yet very important to understand how to shape positive and interative customer journeys with apps and via apps. Table 4 integrates extant conceptual approaches, which include the Innovation Diffusion Theory (Rogers 1995); personality traits theory (McCrae, Costa 1987; John and Srivastava 1999) and value network theory (Peppard and Rylander 2006). It also highlights key priority future research themes and questions.

Brand and partner owned “always on” points of interaction

In accordance with Tong, Luo and Xu (2020), brand and partner owned “always on” points of interaction are linked to the four standard elements of the marketing mix, as follows.

Product (including innovation and branding)

Existing research exploring how apps promote innovation and how to innovate apps is very limited. A few noteworthy exceptions include studies about apps used in specific industries such as construction and higher education—see Lu, Mao, Wang and Hu (2015); Wattanapisit, Teo, Wattanapisit, Teoh, Woo and Ng (2020); Liu, Mathrani and Mbachu (2019); and Pechenkina (2017). However, product innovation research often discusses it in relation to technological developments (Toivonen and Tuominen 2009). Therefore, since mobile technologies are subject to ongoing and rapid technological advancements (Lamberton and Stephen 2016), there is scope for new research empirically evaluating the impact of innovating apps’ technological features. For example, with the advent of apps involving augmented and virtual reality, there is room for studies quantifying the effect of these advancements on downloads and engagement and mobile shopping (in app and via the app). More broadly, more research is needed to reveal the mechanisms through which apps catalyze innovation to generate value for different stakeholders (Snyder, Witell, Gustafsson, Fombelle and Kristensson 2016; Shankar, Kleijnen, Ramanathan, Rizley, Holland and Morrissey 2016). Indeed, it has been argued that apps facilitate the establishment of two-way dialogues between the end-user and key stakeholders (Wong, Peko, Sundaram, and Piramuthu 2016).

Similarly to extant research on app innovation and innovation via apps, studies exploring apps as a branded digital offering or studies clarifying the implications of branding apps are also limited. This is surprising, since Sultan and Rohm (2005) define apps as a ‘brand in the hand’. Similarly, Smutkupt, Krairit and Esichaikul (2010) and Urban and Sultan (2015) argue that mobile technologies offer excellent opportunities for enhancing a brand’s image. Moreover, explicit links between apps and branding objectives appeared in the literature following Bellman et al.’s (2011) formal definition of branded apps and Taivalsaari and Mikkonen’s (2015) definition of ‘brandification’ of apps—i.e., custom-built native apps that enable seamless customer experiences. For example, Stocchi, Guerini and Michaelidou, (2017) link the image of branded apps to their market penetration, while Stocchi, Ludwichowska, Fuller and Gregoric (2020a) propose and validate a simple brand equity framework for apps (c.f. Keller 1993). Accordingly, there is room for new empirical research exploring the implications of branding apps. For instance, future studies could explore the implications of branding and/or extending apps and thus apps’ portfolio management, which is crucial for navigating increasing app competition (Jung et al. 2012). The literature is also missing clarity on what information consumers hold in memory in relation to apps, and how these memories impact knowledge of the app and of the brand powering the app (see also van Noort and van Rejmersdal 2019).

Promotion

Adding to the above, the industry discusses several practices to promote apps (Saxena 2020; Fedorychak 2019)—e.g., App store optimization via keywords and the inclusion of screenshots and videos for greater conversion rate (Karagkiozidou, Ziakis, Vlachopoulou and Kyrkoudis 2019; Padilla-Piernas et al. 2019), or the use of push notifications (Srivastava 2017; Clearbridge Mobile 2019). At the same time, some studies highlight the power of promoting apps via influencers (Hu, Zhang and Wang 2019) or via leveraging user reviews and ratings (Ickin, Petersen and Gonzalez-Huerta 2017; Kübler et al. 2018; Numminen and Sällberg 2017; Hyrynsalmi, Seppänen, Aarikka-Stenroos, Suominen, Järveläinen and Harkke 2015; Liu, Au and Choi 2014). Nonetheless, there is a limited understanding of the implication and effectiveness of promoting apps via these methods. In particular, there is limited knowledge on the effects of advertising apps offline (e.g., via TV advertisements) and online (e.g., on social media or display advertising).

Pricing

Research on pricing strategies for apps is a line of enquiry of its own merit, which started with Dinsmore, Dugan and Wright’s (2016) work exploring the effectiveness of monetary vs. nonmonetary (e.g., data provision) tactics to cue an app’s novelty; and Dinsmore, Swani and Dugan’s (2017) research testing whether personality traits drive the willingness to pay for apps and the willingness to make in-app purchases (see also Natarajan et al. 2017 and Kübler et al. 2018 studies on the implications of price sensitivity for app success). More recently, Arora et al. (2017) clarify that the presence of a free version of the app (sampling) reduces the speed of adoption, and Appel, Libai, Muller and Shachar (2020) also discuss issues inherent to apps’ sampling. Nonetheless, there is scope for more research on improving apps’ monetization and on maximizing the chance of market survival. For instance, future research could evaluate the trade-off between apps’ pricing strategies and other marketing mix elements, especially apps’ advertising and promotion. There are also opportunities for experimental research evaluating the effects of different monetization tactics for different app types. Lastly, although freemium pricing strategies (i.e., free basic app version with subsequent payable upgrades, Arora et al. 2017) are very common, they may not always be a feasible option. Likewise, the decision to market apps at a price may be quite counterproductive in light of the multitude of free alternatives.

Distribution

Although often exceeding the confines of marketing research, there is established knowledge concerning the distribution of apps. For example, Cuadrado and Dueñas (2012) stress the importance of the value network, which includes providers, consumers, platforms, telecommunications, social networks and remote service providers. Within this network, critical factors include feedback, innovation, service quality, device compatibility, ready-to-use services and interfaces (e.g., for data storage, security, automatic updates, notifications and billing), and developers’ diversity. Jung et al. (2012) highlight the relevance of the profit-sharing model of apps’ stores and the review mechanisms, which counteract low entry barriers. Oh and Min (2015) also emphasize the importance of app stores given the increasing pressure for monetization, while Wang, Lai and Chang (2016b) explore different strategies for app competition. At the same time, Roma and Ragaglia (2016) revealed differences in monetization effectiveness across the two leading app stores (Google Play and Apple’s AppStore). Finally, Martin, Sarro, Jia, Zhang and Harman (2017) consider app stores as a channel for communications and feedback crucial to market survival. Hence, although extant research has established that the distribution of apps is bound to the app store’s business model, the need for research clarifying app store’s role in the competitive success of apps is pressing. In particular, future studies could introduce new paradigms for supply chain management and channel integration based on gathering and sharing large amounts of highly-contextualized consumer insights.

Different marketing mix configurations

Besides significant expansions of research considering the four elements of the marketing mix for apps, there is scope for studies exploring different marketing mix configurations. For example, according to Tong et al. (2020), mobile technologies’ marketing mix includes an element of prediction (i.e., the elaboration of considerable amounts of consumer insights), with all elements of the marketing mix enriched by opportunities for personalization. Moreover, since apps are ‘all-in-one’ gateways (Grewal, Hulland, Kopalle and Karahanna 2020) for the asynchronous provision of products and services whereby promotion and distribution are often combined, future research could determine the extent to which apps’ marketing mix elements are somewhat conflated.

Consumer-owned and social “always on” points of interaction

Consumer reviews and peer-to-peer interactions

Although lacking in explicit theoretical grounding, past research confirms that consumer reviews reflect users’ experience with the app, questions and bug reports (Genc-Nayebi and Abran 2017). Indeed, reviews influence the decision to install and use an app (Ickin et al. 2017; Jung et al. 2012; Kübler et al. 2018; Numminen and Sällberg 2017), and the willingness to purchase an app (Huang and Korfiatis 2015; Hyrynsalmi et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2014). Past studies also highlight the impact of negative reviews (Huang and Korfiatis 2015), linking the volume and valence of reviews to app’s sales (Hyrynsalmi et al. 2015; Liang, Li, Yang and Wang 2015). Nonetheless, there is scope for future research exploring the impact of peer-to-peer interactions, embracing new conceptual perspectives such as social contagion (Iyengar, Van den Bulte and Valente 2011) and network effects theory (Katona, Zubcsek and Sarvary 2011). Future research could also examine apps’ role as catalyst of online communities, meeting industry calls for more clarity on how to attain synergies between apps and other crucial aspects of digital marketing (e.g., social media). Finally, from a methodological point of view, there is scope for qualitative research evaluating the social and personal implications of consumer views on apps, adopting lesser explored conceptual lenses such as the notion of the extended self (Belk 1988) or product symbolism (Elliott 1997; Richins 1994). Second, given the obvious differences in the uptake and popularity of apps across different areas of the world, this is a paramount line of future enquiry to evaluate likely cultural differences across all elements of the customer journey. For instance, future studies could evaluate the effects of standard cultural variations in basic demographic features such as age and gender (see McCrae 2002) and the impact of country-level cultural orientations (e.g., in line with Hofstede’s traits, see Johnson, Kulesa, Cho and Shavitt 2005) across all stages of the customer journey with apps, since they are known to impact individual responses and behaviours in numerous settings. Similarly, future studies could examine the impact of individual-level differences linked to specific personality traits that characterise certain cultures across the full customer journey with apps. This is a promising future research avenues, since personality traits have numerous psychological implications (e.g., in terms of cognitive styles—see Oyserman, Coon and Kemmelmeier 2002, and cognitive processes—see Nisbett, Peng, Choi and Norenzayan 2001).

Privacy and personal data management

Privacy in mobile marketing practices is often seen as a result of perceived benefits, which mitigate perceptions of risks and personal data management concerns (Grewal et al. 2020). In line with this view, past studies describe privacy as a risk that impacts the intention to use mobile commerce (Wu and Wang 2005) and specific types of apps such as banking apps (Koenig-Lewis et al. 2015). Similarly, Sultan, Rohm and Gao (2009) examine privacy in relation to the risk inherent to mobile marketing acceptance, and Gao et al. (2013) identify privacy as a potential loss when adopting mobile devices. In contrast, Lu et al. (2007) consider privacy, security and opting out as reflections of trust in wireless environments, a view that led studies evaluating privacy in relation to apps theorize it as a key driver of adoption and/or usage resulting from consumer trust—see Morosan and DeFranco (2015, 2016). Indeed, Miluzzo, Lane, Lu and Campbell (2010) stress the significance of enabling users to control privacy settings. As a result of such contrasting assumptions, besides exacerbating the lack of clarity surrounding privacy in the broader marketing literature (Tan, Qin, Kim and Hsu 2012), extant research provides limited insights on the implications of privacy, loss of privacy and security (i.e., privacy risk) for apps. Hence, there is a clear need for future research clarifying the notion of app privacy—a need, which matches important transnational industry trends to create clear guidelines for personal data collection and usage (see the key issues highlighted in the GDPR guidelines, Gdpr-info.eu 2018). Above all, exploring the acceptable trade-off between apps’ functionality and ubiquity for the secure management of consumer personal data are promising areas of future research. To explore these aspects, future studies could draw upon relevant unexplored conceptual bases such as social justice (Tyler 2020) and ethics theory (Yoon 2011).

‘Blurring’ of the delineation between the firm and the customer

For the customer journey stages and “always on” points of interaction to translate into a digital customer orientation, it is essential to consider extant knowledge that explores apps’ potential in attenuating the divide between the firm and the customer, shaping unique customer experiences; for example, via value creation and co-creation, and consumer response to app technological advancements. Table 5 lists existing theoretical approaches deployed to investigate these aspects, together with priority future research themes and questions worth exploring.

Value creation and co-creation

As previously discussed, the role of perceptions of values in the pre-adoption decision-making process, and in promoting the continuation of the cognitive, affective and behavioral processes inherent to adoption and post-adoption is well-established. Moreover, conceptual research (e.g., Zhao and Balagué 2015) clearly highlights apps’ great potential for value creation. Nonetheless, with a few exceptions (e.g., Ehrenhard, Wijnhoven, van den Broek and Stagno 2017; Kristensson 2019; Lei, Ye, Wang and Law 2020), explicit conceptual and/or empirical assessments of apps’ effectiveness for value creation are limited. This is surprising, since Larivière et al. (2013) suggest that mobile touchpoints trigger a fusion of value, which can simultaneously benefit shoppers, employees and companies. Moreover, Lei et al. (2020) show that, in hospitality, apps facilitate value co-creation by virtue of media richness. A possible reason for the marketing research scarcity in this domain could be the use of a narrow range of theoretical bases. In particular, besides the use of the Dynamic Business Capabilities (DBC) theory (Wheeler 2002), channel expansion theory (Carlson and Zmud 1999) and generic theoretical frameworks evaluating the links between perceptions of value and customer satisfaction (Lin and Wang 2006), there is an absence of research adapting standard customer value theories (e.g., Woodside, Golfetto and Gilbert 2008) and value fusion theory (e.g., Larivière et al. 2013). There is also scope for research clarifying how apps facilitate value co-creation and the marketing potential of co-created apps—i.e., apps shaped through the direct involvement of consumers (see Gokgoz, Ataman and van Bruggen 2021). Indeed, Dellaert (2019) contends that consumer co-production plays a fundamental role in making companies rethink the value creation process. This view matches the service-dominant logic (see Vargo and Lusch 2004; Zhang, Lu and Kizildag 2017), whereby consumers use resources available to them to experience and co-create value (Grönroos 2019). Thus, scholars could research antecedents and outcomes of value creation and co-creation via apps, exploring in detail the appscape (see also Tran, Mai and Taylor 2021). More research is also warranted to understand how apps are used during value exchanges (e.g., in shopping centers, see Rauschnabel et al. 2019) and after value exchanges (e.g., to mitigate purchase regret, see Wedel et al. 2020).

Technological advancements

Extant research contends that technological advancements such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) in apps provide highly customized experiences, impacting consumer preferences and behaviors (Huang and Rust 2017; Pantano and Pizzi 2020). For example, AR-enabled apps improve consumer perceptions of utilitarian and hedonic benefits (Nikhashemi et al. 2021), encourage positive attitudes (Yaoyuneyong et al. 2016; Wedel et al. 2020), and boost purchase intentions and WOM (Yaoyuneyong et al. 2016) through enjoyment (Rauschnabel et al. 2019). Similarly, VR apps elicit positive brand affect by provoking strong sensory reactions such as perceptions of tangibility via haptic vibrations (Wedel et al. 2020). Additionally, through the use of anthropomorphic cues (i.e., human traits assigned to computers, see Nass and Moon 2000), apps enhance user interactions (Alnawas and Aburub 2016) thanks to a humanized customer experience, which influences how consumers perceive the brand attached to the app (van Esch et al. 2019; Olson and Mourey 2019) and increases trust irrespective of privacy concerns (van Esch et al. 2019; Ha et al. 2020). Although on par with current industry trends (the global VR/AR app market is considered one of the most rapidly growing domains of software development see Unity Developed 2021), this stream of research has not exhaustively evaluated the effects of apps’ technological advancements on consumer experiences. Arguably, this knowledge void is caused by dated theoretical bases such as the diffusion of innovation (Rogers 1995), the Uses and Gratification (U&G) theory (Mcguire 1974, Eighmey and McCord 1998) and the Technology Continuance Theory (TCT) (Liao, Palvia and Chen 2009). Hence, future research could embrace new theoretical angles like the physical and psychological continuity theory (Lacewing 2010), teletransportation theory (Langford and Ramachandran 2013) and service prototyping theory (Razek et al. 2018).

Digital customer orientation and competitive advantage

Digital customer orientation

Hyper-contextualized consumer insights

The pervasive nature of mobile technologies generates unprecedented opportunities for hyper-contextualized consumer insights, which include “at which locations consumers are using their mobiles (where), what times they are looking for products (when), how they search for information and complete purchases (how), and whether they are alone or with someone else when using mobile devices (with whom)” (Tong et al. 2020, p. 64). Indeed, due to their built-in features, apps allow gathering, storing, and using these insights, as documented in empirical studies highlighting synergies between apps and CRM (Wang et al. 2016c; Lee 2018a; Newman et al. 2018). Intuitively, the provision of these insights potentially facilitates the realization of digital customer orientation. Nonetheless, as Table 5 shows, the marketing literature is yet to explicitly explore these aspects. Above all, there is room for future research documenting the strategic relevance of consumer insights generated via apps vs. other digital hubs such as web analytics and social media analytics. Moreover, there is scope for evaluating additional implications of information sharing and real-time insights in relation to app personalization. Specifically, apps can enable consumers accessing customized information, strengthening consumer relationships via the provision of superior experiences (Kang and Namkung 2019). However, although studies have considered apps’ personalization potential in frameworks aimed at predicting other aspects of the customer journey (see Tan and Chou 2008; Wang and Li 2012; Watson et al. 2013; Li 2018), more research is needed to esplicitly evaluate the trade-off between personalization and privacy loss. Furthermore, since market segmentation constitutes a key premise to understand and satisfy consumer needs based on relevant insights (e.g., Cooil, Aksoy and Keiningham 2008), there is scope for studying segmentation of apps’ users. In this regard, using cluster analysis, Doub et al. (2018) and Alavi and Ahuja (2016) detect distinct segments in relation to the use of certain types of apps (e.g., for food shopping and mobile banking). In contrast, Kim and Lee (2018) focus on psychographic segmentation of app users, and Kim, Lee and Park (2016) introduce a user-centric service map and a framework for user-value analysis. Finally, Liu et al. (2017) and Chen, Zhang and Zhao (2017) use the Recency, Frequency, Monetary (RFM) approach. Nonetheless, future studies could explore alternative angles such as behavioral segmentation (e.g., delineating between different types of apps’ users based on the usage occasions and frequency of use) and intent-based segmentation (e.g., distinguishing consumers based on stage of customer journey). There is also potential for determining if segments identified in bricks and mortar contexts exhibit different patterns of app usage.

Market intelligence

Thus far, there are only two key studies with a clear focus on market intelligence and competing dynamics. In more detail, using panel data, Jung, Kim and Chan-Olmsted (2014) examine habits and repertoires for different app types by adapting known audience behavior and media concentration benchmarks; and Lee and Raghu (2014) highlight that app competition is configured as a long-tail market (i.e., many choices and low search costs). Therefore, there are multiple avenues for future research advancements in relation to market intelligence (Shapiro 1988) (see Table 5). Above all, there is significant scope for more empirical efforts outlining app competition dynamics, ascertaining likely differences for dissimilar app categories (or sub-markets), and introducing metrics and methods to evaluate app return on investment (see also Gill et al. 2017). These future research endeavors match industry priorities and concerns; indeed, as Dinsmore et al. (2017) state: “…more than 60% of app developers are ‘below the app poverty line’, meaning they generate less than $500 a month from their apps […] and a mere 24% of developers are able to directly monetize their products by charging a fee in exchange for download” (p.227).

Competitive advantage

Lafferty and Hult (2001) attribute the theoretical foundations of market orientation and thus the attainment of competitive advantage to four factors: customer orientation; the strategic use of consumer insights and market intelligence; inter-functional coordination; and strategic implementation. Having already discussed the first two factors, we now concentrate on the latter two, synthesizing the new marketing knowledge required to clarify how to attain a competitive advantage via apps and for apps (see again Table 5).

Inter-functional coordination

An essential premise of market orientation is the effective dissemination of consumer insights and market intelligence across the organizational functions (Lafferty and Hult 2001), striving for the coordination needed to deliver superior customer value (Narver and Slater 1990). Unfortunately, extant marketing research on apps that relates to this matter is currently missing. Therefore, there is potential for examining apps from the perspective of organizational behaviors (see Cadogan 2012), exploring the role of market-orientated behaviors (e.g., product design excellence, see Cyr, Head and Ivanov 2006) in the development, launch and strategic management of apps. For example, future research could evaluate the effects of different managerial approaches, different levels of digital marketing knowledge and the implications of a firm’s overall digital marketing strategy. New studies could also examine the underlying effects of market-level conditions such as market dynamism (i.e., rapid changes in consumer needs and preferences, see again Cadogan 2012).

Strategic implementation

A final foundation of market orientation and pre-condition for attaining competitive advantage is the strategic use of the information in decision-making (Lafferty and Hult 2001), especially within individual business units (Ruekert 1992). It also concerns a significant degree of organizational responsiveness to exogenous factors such as market competition (Kohli and Jaworski 1990). Unfortunately, there is a void on these aspects in the marketing literature on apps. Hence, there is scope for new knowledge uncovering different pathways leading to competitive advantage by deploying apps and for the app. Such studies could seek to determine differences across different industries and businesses. There is also scope for studies quantifying the impact for apps on business growth. Finally, the evaluation of synergies with other crucial strategic aspects, especially attribution marketing, marketing analytics and, more broadly, a firm’s digital marketing strategy, represents a fruitful area of future research.

Conclusions, contributions and limitations

We presented an integrative review of existing marketing knowledge on apps spanning two decades of research and hundreds of studies. The synthesis has been mapped against a meta-theoretical focus (see also Becker and Jaakkola 2020), which integrates core marketing notions such as the customer journey, digital customer orientation and, importantly, value creation and co-creation. The integration of these aspects modifies and expands Lemon and Verhoef’s (2016) customer journey, further enhancing the contribution made in reconciling current views and assumptions. Moreover, the meta-theoretical lens used highlighted significant knowledge voids that need to be addressed to move marketing research on apps forward—an outcome that meets the first key research objective of this study. The synthesis also revealed synergies vs. disconnections between industry trends and academic research on the topic of apps, fulfilling the second research objective. The resulting conceptual and practical contributions are as follows.

Summary of theoretical contributions

Apps can enhance consumer perceptions of value from the early stages of the customer journey. In fact, the decision-making process characterizing the pre-adoption and adoption stages hinges on consumer evaluations of perceived benefits that apps can offer, alongside individual characteristics shaping the chains of effects linking attitudes, intentions and behavioral outcomes signaling adoption. Although more research is needed to better understand potential differences in these mechanisms for different types of apps and different consumer segments, the trigger of positive customer experiences and journeys lies in ensuring that the consumer sees value in the app as a channel to access products and services, and as a two-way platform for seamless interactions. Moreover, at the early stages of the customer journey, different marketing strategies play a crucial role; yet little is known in relation to them. On the contrary, a lot is understood in relation to the value of apps post-adoption as the ultimate marketing vehicle, albeit primarily in instances whereby the app is attached to an existing brand. Therefore, new theoretical and empirical evidence is needed to clarify outcomes for standalone apps beyond mobile shopping implications. In fact, considering existing marketing research on “always on” points of interaction, substantial gaps emerge in relation to apps’ marketing mix—an aspect that is vital for the provision of positive customer experiences and rewarding journeys, and for the creation (and co-creation) of value.

Nonetheless, there are clear opportunities for turning customer journeys for apps and via apps into a competitive advantage. These include realizing a digital marketing orientation, leveraging apps’ power to provide hyper-contextualized consumer insights and personalization opportunities, and harvesting the potential of technological advancements (e.g., VR/AR and AI). There are also ample opportunities for gathering strategically relevant market insights beyond the business model imposed by app stores. In this instance, the key to unlock apps’ potential for the attainment of competitive advantage lies in elevating the digital customer orientation to an all-encompassing market orientation, whereby the consumer insights and market intelligence acquired are shared across organizational functions (beyond marketing) and turned into the input of innovative business strategies. As this integrative review reveals, extant knowledge concerning these aspects is missing and needs to be created to move this field of marketing research on apps forward.

Summary of managerial contributions

Marketing practice relating to apps is ever-evolving. However, a great deal of strategies already in use and guidelines for market success often hinge on opinions, learn-by-doing and, we dare to say, blindly following trends and hypes. Scholarly marketing research can play a vital role in remedying this tendency, as long as extant and well-established findings are clearly communicated and readily available to practitioners. In this regard, our integrative review provides highly simplified summaries that can inform businesses on how to plan app launches and successfully integrate apps into business strategies. In particular, the critical synthesis of marketing knowledge presented serves as a nomological map to understand the depth of existing scholarly research on apps yielding managerial relevance. We stress that these findings often match or complement industry assumptions; in other instances, however, discrepancies emerge alongside missing know-how. Hence, a key practical implication of our integrative synthesis lies in providing a roadmap for addressing these inconsistencies, revealing great scope for more synergy between academia and the industry. Ultimately, it is auspicious to see an increase in information and data porosity through the involvement of the industry in future lines of inquiry mapped in this review. Indeed, for the research directions outlined, access to data and the monitoring of market trends are essential. Likewise, harvesting apps’ full economic potential hinges on accessing rigorous scientific findings.

Upon reading this integrative review, we envision managers of businesses deploying apps to support existing brands and managers of businesses whereby the app is the brand to embrace important strategic guidelines that emerged such as: (i) the role apps play in the media ecosystem and/or as a marketing channel, ensuring consumers enjoy seamless value-generating experiences; (ii) the importance of marketing apps via offering clear benefits that match strategic priorities of a business; and (iii) the existence of untapped strategic power for apps for the attainment of competitive advantage, especially upon gathering and using consumer insights and market intelligence above and beyond the marketing function.

Limitations and general future research directions

Our review approach entailed a combination of bibliometric analysis and a more intuitive process whereby research themes were detected and iteratively refined. Although considerable alignment emerged between these two steps, the approach inevitably resulted in some arbitrary choices. For instance, we did not focus on aspects involving the development and supply of apps; similarly, technological aspects of apps’ programing and design were not considered. Therefore, future research could pursue alternative routes such as presenting a meta-analysis of the extant empirical findings. Moreover, the reconciliation of views from academia and industry has been fulfilled by juxtaposing industry trends and assumptions with the summaries of findings extracted from the body of scholarly work reviewed. Future studies could present more explicit analyses of industry views, such as conducting primary research involving managers and app developers. Finally, future development of the outcomes of this integrative review calls for a more detailed evaluation of interdisciplinary links, detecting and exploring in more detail the connections between marketing knowledge and other relevant fields such as information technology, information management and organizational behavior.

Notes