Abstract

Biological sex and sociocultural gender matter when it comes to health and diseases. They have been both proposed as the undeniable gateways towards a personalized approach in care delivery. The Gender Working Group of the Italian Society of Internal Medicine (SIMI) was funded in 2019 with the aim of promoting good practice in the integration of sex and gender domains in clinical studies. Starting from a narrative literature review and based on regular meetings which led to a shared virtual discussion during the national SIMI congress in 2021, the members of the WG provided a core operational framework to be applied by internal medicine (IM) specialists to understand and implement their daily activity as researchers and clinicians. The SIMI Gender ‘5 Ws’ Rule for clinical studies has been conceptualized as follows: Who (Clinical Internal Medicine Scientists and Practitioners), What (Gender-related Variables—Gender Core Dataset), Where (Clinical Studies/Translational Research), When (Every Time It Makes Sense) and Why (Explanatory Power of Gender and Opportunities). In particular, the gender core dataset was identified by the following domains (variables to collect accordingly): relations (marital status, social support, discrimination); roles (occupation, caregiver status, household responsibility, primary earner, household dimension); institutionalized gender (education level, personal income, living in rural vs urban areas); and gender identity (validated questionnaires on personality traits). The SIMI Gender ‘5 Ws’ Rule is a simple and easy conceptual framework that will guide IM for the design and analysis of clinical studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The awareness that biological sex (i.e., sex assigned at birth) and sociocultural gender (i.e., sociocultural norms roles and expectations) are relevant modifiers of health and disease has been a recent achievement by the life sciences researchers and clinicians [1]. Despite the advocacy of international societies and gender champions to promote the knowledge on sex and gender analysis for improving the quality of science, the terms are still often used interchangeably, yet they capture different aspects of a person. Specifically, gender refers to the psychosocial aspects of being a woman or a man (“psychosocial sex”) as opposed to the biological aspects of being male or female (“biological sex”) [2]. However, some males and females may report gender-related characteristics traditionally attributed to the opposite sex, and some individuals may identify as neither male nor female thereby leading to the increasing recognition of gender as a spectrum (rather than binary entity) in social sciences and the general public. As such, the distribution of gender-related characteristics within populations of men and women is likely to influence health differently than biological sex. To underline the different meaning of these terms, from 2012 the Canadian Institute of Gender and Health acknowledges that “Every cell is sexed, and every person is gendered” [3] pointing out how biological factors (sex-based) and psycho-socio-cultural factors (gender-related) contribute profoundly to shape who we are either in maintaining health status or in developing diseases. Furthermore, the concept of intersectionality between sex, gender, and other social factors (e.g., race, immigration status, etc.) is currently emerging to reflect the importance of diversity in health [4, 5]. An intersectional framework assumes that an individual’s experiences are not simply equal to the sum of their parts but represent intersections of social power’s axes. For example, the health-related experiences of immigrant women may be different from those of immigrant men and non-immigrant women. The term intersectionality, originally coined in the critical race theory is considered an extension of sex and gender analysis and can be applied across other social identities or positions in society [4, 5].

The specialty of internal medicine (IM) is an all-embracing medical discipline, dealing with all aspects of pathology and organ-based specialties [6]. The IM specialists face every day the challenges of a 360-degree approach to the care of complex and multimorbid and often older individuals. IM healthcare professional are those that would mostly benefit from a sex- and gender-based evidence as they traditionally build their clinical decisions on a multidimensional evaluation of patients beyond the disease-centered focus. Therefore, clinical investigators working in the IM field should recognize the value of a sex- and gender-oriented approach to answer relevant research questions and should be supported with strategies for incorporating sex and gender-related variables when conducting either pre-clinical or clinical studies.

The aim of this study was to build an operational framework that can guide IM researchers in implementing their approach giving the context and the content on how to practically perform it.

Methods

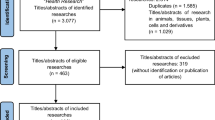

During the 2019 National Congress of the Italian Society of Internal Medicine (SIMI) held in Rome (Italy), a Working Group (WG) on Gender Medicine has been implemented with the specific aim of promoting the integration and application of sex- and gender-oriented approaches in internal medicine (IM) from research to clinical practice. In this context, the first goal of the WG was to implement the strategy for the collection of gender-related variables in the no-profit observational studies promoted by SIMI. Starting from a narrative detailed and extensive literature analysis on the applicable tools for the gender-based data acquisition in human studies, the WG met on regular basis and discussed the most simple and feasible strategy for promoting among the IM community. In a dedicated session of the virtual 2021 SIMI National Congress, the WG collegially agreed on the most appropriate approach for the implementation of a sex- and gender-sensitive framework in clinical studies promoted by the SIMI. Specifically, the WG SIMI Gender has formulated a short three-question questionnaire to assess whether the session participants were able to define properly the terms ‘sex’ and ‘gender’. Then the core dataset of variables to be incorporated in the design of the clinical studies promoted by SIMI was voted, and afterwards the perception of participants regarding the best way to inquire patients on their gender identity was discussed.

Results

The activities of the WG SIMI Gender led to the operational definition of the SIMI Gender ‘5 Ws’ Rule for clinical studies which have been conceptualized as summarized in Who, What, Where, When, and Why (Fig. 1).

Who—clinical internal medicine scientists and practitioners

In their clinical activity IM specialist often rely practice on evidence that do not always reflect the real-world scenarios [6]. For example, in drugs prescription while it is well-recognized that the proportion of female participants to interventional randomized control trials is far lower than the male counterpart, the results on drugs efficacy and safety are usually transferred and generalized to all people, when they should not [7]. According to data arising from a survey started by the ‘Internal Medicine Assessment of Gender differences IN Europe’ (IMAGINE), a working group of the European Federation of Internal Medicine, the largest society of Internists in Europe, the awareness of sex/gender issues in the European internal medicine community is already high, reaching approximately 80% of participants [8]. Therefore, the internal medicine community represents a solid bedrock where implement sex/gender strategies when it comes to planning research activities and clinical trials.

What (and how) gender-related variables—gender core dataset

The collection of gender-related variables has been proposed in 20 s’ through questionnaires that included questions pertinent to each of the four domains that gender encompasses (i.e., gender identity, relations, roles, and institutionalized gender) [2]. Interestingly in 2016 Canadian investigators proposed the collection of gender-relevant variables through self-administered questionnaire and then developed a methodology to combine the data to generate a composite measure of gender, the gender score [9] as part of the ‘GENdEr and Sex DetermInantS of Cardiovascular Disease: From Bench to Beyond Premature Acute Coronary Syndrome’ (GENESIS-PRAXY) study [10]. Numerous variables (for the most part previously validated questions from literature), covering the four gender aspects (i.e., gender roles, gender identity, gender relations, and institutionalized gender) were identified and them to create a questionnaire for a cohort of young individuals with acute coronary syndrome. Through Principal Component Analysis (PCA), the Authors identified the gendered variables most associated with sex (primary earner status, personal income, number of hours per week doing housework, level of stress at home, Bem sex role inventory (BSRI) masculinity score and BSRI femininity score) and used them to create a composite gender score. Furthermore, gender score predicted recurrence of cardiovascular events, and showed that individuals with characteristics that society traditionally ascribed to women, regardless of sex, had worse outcomes. Some criticisms have been raised by such approach in clinical practice. One challenge in applying these methods is attributed to the use of a long questionnaire comprised of 32 components. This length renders it unpractical and not user-friendly among researchers. Moreover, designing a composite gender score may compromise the ability to identify which aspects of gender most importantly impact health outcomes. Finally, it is important to determine whether the results obtained from the GENESIS-PRAXY study, a cohort of patients with cardiovascular disease, are repeatable or different in other clinical contexts.

The applicability of the GENESIS-PRAXY methodology using retrospective cohorts have been tested in other contexts [11, 12] and systematically incorporated as a potential tool in the application of the ‘Gender Outcomes International Group: to Further Well-being Development’ (GOING-FWD framework [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. The GOING-FWD methodology has led to understand more clearly the effect of gender on outcomes also in population-based health surveys and in diverse clinical scenarios. The most intriguing finding is that the gender-related factors included in the gender score measure vary by countries underlying the cultural and country-specific nature of gender [15,16,17,18,19].

As the debate on the best way for measuring the impact of gender on health outcomes is a moving field, other proposals have been published. In 2021, a gender assessment tool—the Stanford Gender-Related Variables for Health Research—for use in clinical and population research [20] has been proposed. Specifically, seven main variables should be captured in health research including caregiver strain, work strain, independence, risk-taking, emotional intelligence, social support, and discrimination.

Based on the abovementioned literature we have constructed an Italian version of the self-administered questionnaire to collect sex and gender-relevant variables in clinical studies (Table 1). The main findings of this interactive web-based discussion session were: (1) the majority of attendees were able to identify a gender-related variable; (2) the variables to be included in the core dataset should be gender relations (i.e., marital status, social support, discrimination); gender roles (i.e., occupation, caregiver status, household responsibility, primary earner, household dimension); and institutionalized gender (i.e., education level, personal income, living in rural vs urban areas); (3) validated questionnaires on personality traits are considered the most feasible approach to explore individuals’ perception of gender identity rather than a direct question “how do you perceive your identity regardless of the sex you were assigned at birth”.

Where—clinical studies/translational research

The members of the WG agreed that the impact of sex as biological variable and gender as sociocultural variable should be assessed in observational and cohort studies. Whenever there is a database with already collected clinical data or in designing a study to answer a specific research question, the availability of gender-related variables should be pursued.

Furthermore, since IM scientists may well be involved also in translational research, the members of the WG recognize that the integration of sex and gender-based approach should permeate every phase of research from bench to bedside. Identifying the sex and gender differences in the mechanism, disease or treatment under investigation is always a priority.

When—Every time it makes sense

The member of the WG strongly recommend defining clearly from the beginning the gender-oriented conceptual framework that the clinical scientists expect to be plausible in a specific clinical context. In this light it is crucial to run preliminarily a literature review on what is already known in terms of sex and gender impacts on the exposures and outcomes of interest. The advice to clinical scientists is first to ask themselves “Is gender as socio-cultural factor relevant for my research question?”. Here both ‘yes’ and ‘no’ answers need to have a proper justification. Then, if the answer is yes, how the gender domains can be integrated into the research proposal (i.e., research design, methods, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination of findings) should be addressed.

Why—Explanatory power of gender and opportunities

The members of the WG defined the meaningfulness of the approach proposed. The main reason for integrating sex and gender domains in clinical research is to produce better, equitable and high-quality science. [21]

A sex- and gender-blinded approach in data collection can lead to false findings and increase the likelihood of missing critical opportunities to discover differences in the interplay between exposures and outcomes for individuals which could inform future interventions. When research fails to account for sex and gender there is a risk of harm in assuming that the results apply to everyone. Indeed, the explanatory power of sex and gender in overt differences of disease under study as well as a different response to treatment should favor the development of more tailored approaches to care. The understanding of how gender-related factors can generate differences in health outcomes across the spectrum of genders is undoubtedly a strategy to address any underlying causes of inequities.

Discussion

The SIMI Gender ‘5 Ws’ Rule represents an easy and pragmatic guide for any internist interested in improving scientific research and disseminating scientific knowledge for the benefit of all patients. In the era of precision medicine, we are currently going through, sex and gender are the gateways to achieve a personalized approach in both research and clinical practice.

The bottom line of the Gender Medicine is that sex and gender permeate the life of people, therefore, when it comes to health they are theoretically always involved. Therefore, a sex and gender-based consideration should be pursued almost always, specifically when an impact on outcomes is envisaged. In fact, gender domains capture a huge group of factors that are broadly recognized as mediators or modifiers of outcomes. The collection of gender-related variables is still an unmet need and the truly gamebreaker when it comes to provide high-quality science. The What of the SIMI Gender ‘5 Ws’ Rule was built upon the previous literature exploring the feasibility of measure gender. In fact, the first hurdle clinician faces in the integration of sex and gender domains is to operationalize the definition of a gender-related variable. Specifically, a gender-related variable is a non-biological variable which differs in terms of magnitude, prevalence, and/or impact between people regardless of the sex they were assigned at birth. As shown by our literature review, there is a lack of a standardized method for embracing the multidimensionality of gender. Depending on the availability of data it might be worthy to test the effect of gender using a composite measure as was performed by GENESIS-PRAXY Investigators [9, 10]. The methodology of constructing the gender score has been validated since the inception in cohorts from retrospective and prospective studies [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Furthermore, international scientists have been supporting the assessment of even one domain or few individual gender-related factors depending on the availability of data [20,21,22].

The WG also acknowledges that over the last decade both funding agencies and medical journals are promoting for the excellence of science to assess a research protocol or publication based on the integration or omission of sex and/or gender. In fact, Canadian, American, and European research funding agencies supported by governments have implemented different strategies to favor the inclusion of sex and gender-based considerations in the grant’s procedure with the ultimate goal of awarding those protocols that integrate diversity and justify why sex and gender have been evaluated. [23]

Sex and gender matter when it comes to data analysis and reporting the findings of the clinical research. Of interest, stop controlling for sex [24] and favor sex-stratified analyses and interaction analyses [13, 14, 21] are recommendations that the scientific community is promoting to ensure equitable evidence at glance of practitioners for male and female individuals.

Finally, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors recommends that the use of terms sex (when reporting biological factors) and gender (identity, psychosocial or cultural factors) should be guaranteed throughout the entire manuscript and, unless inappropriate, Authors should report the sex and/or gender of study participants, the sex of animals or cells, and describe the methods used to determine sex and gender [25].

Conclusions

The IM community recognize that biological sex and sociocultural gender (i.e., societal norms, roles, and expectations) are relevant modifiers of health and disease. The application of sex and gender lenses in informing our understanding of health maintenance and disease development is key to personalize approaches and provide patient-centered care. The first obstacle to the integration of sex and gender in clinical practice and research is the lack of the habit to collect a granularity of sex- and gender-related variables in the case report forms of clinical research studies. The Gender WG of the SIMI identified and proposed an operational framework the SIMI Gender ‘5 Ws’ Rule to guide IM researchers in the challenging attempt of performing an equitable research with meaningful findings for improving the health of all patients.

References

Mauvais-Jarvis F, Bairey Merz N, Barnes PJ, Brinton RD, Carrero JJ, DeMeo DL, De Vries GJ, Epperson CN, Govindan R, Klein SL, Lonardo A, Maki PM, McCullough LD, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Regensteiner JG, Rubin JB, Sandberg K, Suzuki A (2020) Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet 396(10250):565–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31561-0

Johnson JL, Greaves L, Repta R (2009) Better science with sex and gender: facilitating the use of a sex and gender-based analysis in health research. Int J Equity Health 8:14

Canadian Institute of Gender and Health Website–Shaping Science for a Healthier World https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48633.html Accessed date: 2nd Oct 2022

Bauer GR, Churchill SM, Mahendran M, Walwyn C, Lizotte D, Villa-Rueda AA (2021) Intersectionality in quantitative research: a systematic review of its emergence and applications of theory and methods. SSM Popul Health 16(14):100798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100798

Bauer GR (2014) Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc Sci Med 110:10–17

Pietrangelo A (2022) Internists or specialists-that is the question! Eur J Intern Med 98:41–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2022.02.011

Mauvais-Jarvis F, Berthold HK, Campesi I, Carrero JJ, Dakal S, Franconi F, Gouni-Berthold I, Heiman ML, Kautzky-Willer A, Klein SL, Murphy A, Regitz- Zagrosek V, Reue K, Rubin JB (2021) Sex-and gender-based pharmacological response to drugs. Pharmacol Rev 73(2):730–762. https://doi.org/10.1124/pharmrev.120.000206

Biskup E, Marra AM, Ambrosino I, Barbagelata E, Basili S, de Graaf J, Gonzalvez-Gasch A, Kaaja R, Karlafti E, Lotan D, Kautzky-Willer A, Perticone M, Politi C, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Vilas-Boas A, Roeters van Lennep J, Gans EA, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Pilote L, Proietti M, Raparelli V, Internal Medicine Assessment of Gender differences IN Europe (IMAGINE) Working group within the European Federation of Internal Medicine (EFIM) (2022) Awareness of sex and gender dimensions among physicians: the European federation of internal medicine assessment of gender differences in Europe (EFIM-IMAGINE) survey. Intern Emerg Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-022-02951-9

Pelletier R, Ditto B, Pilote L (2015) A composite measure of gender and its association with risk factors in patients with premature acute coronary syndrome. Psychosom Med 77(5):517–526. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000186

Pelletier R, Khan NA, Cox J, Daskalopoulou SS, Eisenberg MJ, Bacon SL, Lavoie KL, Daskupta K, Rabi D, Humphries KH, Norris CM, Thanassoulis G, Behlouli H, Pilote L, GENESIS-PRAXY Investigators (2016) Sex versus gender-related characteristics: which predicts outcome after acute coronary syndrome in the young? J Am Coll Cardiol 67(2):127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.067

Nauman AT, Behlouli H, Alexander N, Kendel F, Drewelies J, Mantantzis K, Berger N, Wagner GG, Gerstorf D, Demuth I, Pilote L, Regitz-Zagrosek V (2021) Gender score development in the Berlin Aging Study II: a retrospective approach. Biol Sex Differ 12(1):15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-020-00351-2

Pohrt A, Kendel F, Demuth I, Drewelies J, Nauman T, Behlouli H, Stadler G, Pilote L, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Gerstorf D (2022) Differentiating sex and gender among older men and women. Psychosom Med 84(3):339–346

Raparelli V, Norris CM, Bender U, Herrero MT, Kautzky-Willer A, Kublickiene K, El Emam K, Pilote L, GOING‑FWD Collaborators (2021) Identification and inclusion of gender factors in retrospective cohort studies: the GOING-FWD framework. BMJ Glob Health 6(4):e005413. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005413

Tadiri CP, Raparelli V, Abrahamowicz M, Kautzy-Willer A, Kublickiene K, Herrero MT, Norris CM, Pilote L, GOINGFWD Consortium (2021) Methods for prospectively incorporating gender into health sciences research. J Clin Epidemiol 129:191–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.08.018

Raparelli V, Pilote L, Dang B, Behlouli H, Dziura JD, Bueno H, D’Onofrio G, Krumholz HM, Dreyer RP (2021) Variations in quality of care by sex and social determinants of health among younger adults with acute myocardial infarction in the US and Canada. JAMA Netw Open 4(10):e2128182. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28182

Tadiri CP, Gisinger T, Kautzky-Willer A, Kublickiene K, Herrero MT, Norris CM, Raparelli V, Pilote L, GOING-FWD Consortium (2021) Determinants of perceived health and unmet healthcare needs in universal healthcare systems with high gender equality. BMC Public Health 21(1):1488. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11531-z

Azizi Z, Gisinger T, Bender U, Deischinger C, Raparelli V, Norris CM, Kublickiene K, Herrero MT, Emam KE, Kautzky-Willer A, Pilote L, GOING-FWD investigators (2021) sex, gender, and cardiovascular health in Canadian and Austrian populations. Can J Cardiol 37(8):1240–1247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2021.03.019

Azizi Z, Shiba Y, Alipour P, Maleki F, Raparelli V, Norris C, Forghani R, Pilote L, El Emam K, GOING-FWD investigators; GOING FWD Investigators (2022) Importance of sex and gender factors for COVID-19 infection and hospitalisation: a sex-stratified analysis using machine learning in UK Biobank data. BMJ Open 12(5):e050450. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050450

Dev R, Raparelli V, Pilote L, Azizi Z, Kublickiene K, Kautzky-Willer A, Herrero MT, Norris CM, GOING-FWD Consortium* (2022) Cardiovascular health through a sex and gender lens in six South Asian countries: findings from the WHO STEPS surveillance. J Glob Health 12:04020. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.12.04020

Nielsen MW, Stefanick ML, Peragine D, Neilands TB, Ioannidis JPA, Pilote L, Prochaska JJ, Cullen MR, Einstein G, Klinge I, LeBlanc H, Paik HY, Schiebinger L (2021) Gender-related variables for health research. Biol Sex Differ 12(1):23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-021-00366-3

Tannenbaum C, Ellis RP, Eyssel F, Zou J, Schiebinger L (2019) Sex and gender analysis improves science and engineering. Nature 575(7781):137–146. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1657-6

Mele BS, Holroyd-Leduc JM, Harasym P, Dumanski SM, Fiest K, Graham ID, Nerenberg K, Norris C, Parsons Leigh J, Pilote L, Pruden H, Raparelli V, Rabi D, Ruzycki SM, Somayaji R, Stelfox HT, Ahmed SB (2021) Healthcare workers’ perception of gender and work roles during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 11(12):e056434. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056434

White J, Tannenbaum C, Klinge I, Schiebinger L, Clayton J (2021) The integration of sex and gender considerations into biomedical research: lessons from international funding agencies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 106(10):3034–3038. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgab434

Shapiro JR, Klein SL, Morgan R (2021) Stop ‘controlling’ for sex and gender in global health research. BMJ Glob Health 6(4):e005714. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005714

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (2022) Preparing a Manuscript for Submission to a Medical Journal. Available at http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/manuscript-preparation/preparing-for-submission.html. Accessed date: 22nd Feb 2022

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Dr Antonello Pietrangelo, the President of the Italian Society of Internal Medicine (SIMI) who promoted the foundation of the Gender Medicine Working Group in the 2019. We also thank the members of the SIMI for the contribution provided during the 2021 National Congress of SIMI.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Ferrara within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors have no disclosures to declare.

Ethical approval

Not applicable. This work is based on experts' consensus statements. Each author has read and approved the final version of the manuscript and made important contributions to the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raparelli, V., Santilli, F., Marra, A.M. et al. The SIMI Gender ‘5 Ws’ Rule for the integration of sex and gender-related variables in clinical studies towards internal medicine equitable research. Intern Emerg Med 17, 1969–1976 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-022-03049-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-022-03049-y