Abstract

COVID-19 infection causes respiratory pathology with severe interstitial pneumonia and extra-pulmonary complications; in particular, it may predispose to thromboembolic disease. The current guidelines recommend the use of thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19, however, the optimal heparin dosage treatment is not well-established. We conducted a multicentre, Italian, retrospective, observational study on COVID-19 patients admitted to ordinary wards, to describe clinical characteristic of patients at admission, bleeding and thrombotic events occurring during hospital stay. The strategies used for thromboprophylaxis and its role on patient outcome were, also, described. 1091 patients hospitalized were included in the START-COVID-19 Register. During hospital stay, 769 (70.7%) patients were treated with antithrombotic drugs: low molecular weight heparin (the great majority enoxaparin), fondaparinux, or unfractioned heparin. These patients were more frequently affected by comorbidities, such as hypertension, atrial fibrillation, previous thromboembolism, neurological disease, and cancer with respect to patients who did not receive thromboprophylaxis. During hospital stay, 1.2% patients had a major bleeding event. All patients were treated with antithrombotic drugs; 5.4%, had venous thromboembolism [30.5% deep vein thrombosis (DVT), 66.1% pulmonary embolism (PE), and 3.4% patients had DVT + PE]. In our cohort the mortality rate was 18.3%. Heparin use was independently associated with survival in patients aged ≥ 59 years at multivariable analysis. We confirmed the high mortality rate of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients in ordinary wards. Treatment with antithrombotic drugs is significantly associated with a reduction of mortality rates especially in patients older than 59 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) is a viral illness caused by the RNA betacoronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2). The first pneumonia cases of unknown origin were identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. After few weeks, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the pandemic. (WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19–11 March 2020).

After the diffusion in China, Italy was the first country severely interested by the pandemic, with a widespread diffusion especially in Northern Italy [1]. COVID-19 infection causes respiratory pathology with severe interstitial pneumonia, but also causes several extra-pulmonary complications. In particular, COVID-19 may predispose to both venous and arterial thromboembolic disease due to excessive inflammation, hypoxia, and immobilization. Moreover, it has been described a COVID-19-associated coagulopathy that may further increase the thrombotic risk [2,3,4,5]. COVID-19 patients may show marked increase of inflammatory markers, as well as signs of endothelial dysfunction, platelet activation, and hypercoagulability [6]. The mortality rate is high, even if differences have been reported across published studies, ranging from 16 to 78% of patients who required hospital admission. Several factors associated with a high risk for death in these patients were described, in particular comorbidities such as hypertension, coronary heart disease and diabetes [7,8,9,10,11]. Among, predictors of mortality, also COVID-19 associated coagulopathy has been associated with poor outcome [2, 12, 13]. Given the high risk of venous thromboembolism and the role of coagulopathy on patient outcomes, current guidelines recommend the use of thromboprophylaxis for patients with COVID-19 [14,15,16,17]. However, the optimal dosage of heparin treatment is not known and the need for intermediate or therapeutic heparin doses has been proposed. However, there is concern on the bleeding risk associated with the higher heparin dosage [16, 18,19,20].

We conducted a multicentre, Italian nationwide, retrospective, observational study on COVID-19 patients admitted to ordinary wards, to describe the demographics, baseline comorbidities, laboratory tests at presentation, bleeding and thrombotic events occurring during hospital stay. We also aimed to describe strategies used for thromboprophylaxis and to assess the characteristics of patients who received different doses heparin, either prophylactic or sub-therapeutic/therapeutic dosage.

Methods

The START-COVID-19 Register starts in May 2020 after the widespread of the SARS2-COVID-19 pandemic in the frame of the START Register (NCT 02219984) [21]. This is a retrospective, observational, nationwide, multicentre register aimed to collect data on the clinical characteristics, laboratory findings, and drugs employed in patients infected by SARS2-COVID-19 virus, hospitalized in ordinary wards. Patients requiring ICU at admission were excluded from the study. The registry has been approved by the Ethical Committee of the Institution of the Coordinating Member (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria, Policlinico S. Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Italy), and by all Ethical Committees of participating centers. Twenty-two hospitals distributed throughout Italy participate in these data collection.

The Registry is aimed to record local practice, therefore no specific tests or treatments were mandated by the study protocol. All patients underwent to nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab on admission, and the presence of SARS2-COVID-19 infection was detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method. The study focused in particular to the type and dosage of the thromboprophylaxis used, the occurrence of adverse thrombotic and bleeding events, and of death. A dedicated web-based case report form (e-CRF) obtained with “Electronic Data Capture” (EDC) system, based on the “Research Electronic Data Capture” online platform (REDCap, produced and distributed by Vanderbilt University and “REDCap Consortium”) [22]. The e-CRF collect demographic data, clinical data related to associated diseases, symptoms at admission, and type of treatment. The entity of associated comorbidity was measured using the Charlson’s comorbidity index [23]. Antithrombotic therapy was defined prophylactic when enoxaparin 4000–6000 U od, or fondaparinux 2.5 mg od, or nadroparin 2850-3800-5700 U od, or unfractioned heparin (UFH) 5000 U bid, were used. Treatment was defined sub-therapeutic/therapeutic when enoxaparin 4000 U bid, or enoxaparin 6000 U bid, or enoxaparin 8000 U bid, or fondaparinux 5–7.5 mg od, or nadroparin 3800 U bid or 5600 U bid, or UFH 12.500 U bid, were used. In addition, to evaluate the role of thromboprophylaxis in relation to age, we divided the patients taking into account the quartiles distribution of age. We decided to stratify patients into 2 classes: patients < 59 years (1° quartile) and patients with age ≥ 59 years (≥ 2° quartile).

Patients were followed-up during hospital stay, the follow-up ended when the patients was discharged, transferred to ICU, or died. The outcome was defined favourable when the patient was discharged, and severe when the patient was transferred to ICU or died. Thrombotic and bleeding events occurred during follow-up were recorded. Objective confirmation of thrombotic events was requested. Major bleeding (MB) was defined according with the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis [24]. Clinically relevant non major bleedings (CRNMB) were defined as those events that are not major but require any kind of medical intervention [25].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed. Continuous variables are expressed as median with interquartile range (IQR) or as mean plus or minus standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Preliminary statistical analysis was performed using Wilcoxon signed-rank test (continuous variables) or Fisher exact test (categorical data). A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A logistic univariate analysis was performed to estimate the association of heparin use and mortality. All significant variables were subsequently entered into a multivariable analysis. Risk was expressed as odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI. A 2-sided value of p < 0.05 was chosen for statistical significance.

We used the SPSS version 26 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) and the Stata version 14 software (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) for Windows for data processing.

Results

Patients and thromboprophylaxis

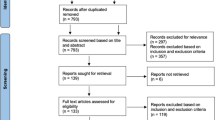

From March 1st and June 30th 2020, 1135 patients hospitalized for COVID-19 infection were included in the START-COVID-19 Register. The flow chart of the study is available Fig. 1; 1091 patients were included (59.9% males), with a median age of 71 years (IQR 59–82 years). Characteristics of the patients are detailed in Table 1. In particular, hypertension was present in 570 (52.2%) patients, the median Charlson’s index of the cohort was 3 (range 2–5), and 406 (37.2%) patients had no associated comorbidities. At admission, fever was present in 796 patients (73.0%), dyspnoea in 581 (53.3%), and cough in 450 (41.2%).

During hospitalization, 508 (46.6%) patients received antiviral treatment, mainly lopinavir/ritonavir [379/508 patients (74.6%)]; 851 (78.0%) patients hydroxychloroquine, and 240 (22%) desametasone. At admission, 51 (4.7%) patients were on oral anticoagulants: 35 (68.6%) with vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and 16 (31.4%) with direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) (Table 2); 23 patients were already receiving low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH) at prophylactic dosage.

During hospital stay, 769 (70.7%) patients were treated with antithrombotic drugs: 15 (2.0%) patients continued treatment with oral anticoagulants, and 754 (98.0%) were treated with LMWH/fondaparinux/unfractioned heparin (UFH). Among these patients, 607 (78.9%) received prophylactic dosage, 93 (12.1%) received sub-therapeutic dosage, and 69 (9.0%) therapeutic dosage. The great majority of patients were treated with enoxaparin (92.3%). The characteristics of patients treated with prophylactic dosage and with sub-therapeutic/therapeutic dosage are reported in Table 3. Atrial Fibrillation (AF), previous thromboembolism, neurological disease, and cancer were less frequent in patients who did not receive prophylaxis in comparison to patients who received prophylaxis. Accordingly, in the latter group the Charlson’s score was significantly higher. Patients who received antithrombotic treatment at sub-therapeutic/therapeutic dosage, had higher prevalence of AF and coronary artery disease with respect to patients who received prophylactic dosage (Table 4).

Bleeding and thrombotic complications

During hospital stay, 9 (1.2%) patients had a major bleeding (MB) and 9 (1.2%) patients a clinically relevant non major bleeding (CRNMB). All bleedings occurred among patients treated with antithrombotic drugs. MBs and CRNMBs occurred more frequently among patients treated with sub-therapeutic/therapeutic dosage with respect to patients treated with prophylactic dosage [5 (3.1%) and 6 (3.7%) vs 4 (0.7%) and 3 (0.5%), respectively] (Table 4). Fifty-nine patients had venous thromboembolism during observation (5.4%), 18 (30.5%) patients had deep vein thrombosis (DVT), 39 (66.1%) patients had pulmonary embolism (PE), and 2 (3.4%) patients had DVT + PE.

Clinical deterioration and mortality

Favourable outcome was reported in 806/1091patients (73.9%). Among patients with severe outcome, 85 (7.8%) were transferred to ICU, due to deterioration of respiratory failure, and 200 patients (18.3%) died (Fig. 1). Clinical characteristics of patients with fatal outcome and of discharged patients are reported in Table 5. Patients with fatal outcome were significantly older with respect to patients discharged, showing higher prevalence of hypertension, of coronary artery disease, of peripheral artery obstructive disease (POAD), of cerebrovascular and neurological disease, of cancer, and a higher median Charlson’s comorbidity index (Table 5). Patients who did not had comorbidities at admission were significantly less represented among patients who died with respect to patients with favourable outcome. Laboratory tests showed that median D-dimer levels and PT ratio were significantly higher in patients with fatal outcome with respect to discharged patients (data not shown).

To evaluate the association of fatal outcomes with antithrombotic treatment, we performed a logistic regression multivariable analysis on patients considering the different quartiles of age. Antithrombotic treatment resulted independently associated with survival in patients aged ≥ 59 years (≥ 2° quartile) (Table 6).

Discussion

In this study, we describe the characteristics of 1091 patients admitted to general wards for laboratory confirmed infection by COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic in Italy, focusing the attention on the antithrombotic treatment and its association with patient outcomes. Mortality of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 varies significantly among the published case series, ranging from 16% to more than 50% [6, 26,27,28]. In our cohort the mortality rate was 18.3%, higher than that reported from other studies conducted in China [29, 30]. However, it was similar to the case fatality rate observed by Wu C et al. [31] in the early period of the epidemic in China, in New York [8] and in Italy [1, 7, 32], In particular the CORIST study [32], conducted in Italian hospitals, reported almost the same mortality rate as in our study. The variability of the mortality rate described in the studies can be explained by different organization of hospitals and of out-of-hospital health services, leading to a different severity of patients for whom hospital admission is required. In any case, the mortality rate is very high when patients require treatment in ICU wards.

Overall, published data identify advanced age as the principal risk factor for mortality, and for this reason the ongoing vaccination campaigns are directed firstly to the elderly subjects. In our cohort, patients with fatal outcome had a median age of 83 years, confirming the previous finding, instead a median age of 68 years was reported for survivors.

In our patients, several other risk factors have been associated with fatal outcome, in particular hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, active cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and renal failure, as described from other authors [10].

In our cohort 769 (70.7%) patients were treated with antithrombotic drugs during hospital stay, mainly with enoxaparin, that was used in 92.3% of patients. These patients were more frequently affected by comorbidities, such as hypertension, AF, previous thromboembolism, neurological disease, peripheral artery obstructive disease (POAD), and cancer with respect to patients who did not receive thromboprophylaxis. Despite the elevated number of associated risk factors, the mortality rate in this group was lower than that recorded in patients who did not receive heparin. This finding was confirmed at multivariate analysis especially when older patients, aged ≥ 59 years, were considered. The protective effect of heparin was not detected in patients < 59 years, who showed a low mortality rate (only 4 patients had fatal outcome in this group). The presence of POAD and of neurological diseases were also independently associated with mortality, probably as a consequence of the high frequency of coronary artery disease and renal failure usually associated with these clinical conditions.

Patients treated with heparin at prophylactic dosage showed a lower bleeding risk, in comparison to patients treated with sub therapeutic/ therapeutic dosages. The increased bleeding risk associated with the use of sub therapeutic/ therapeutic dosages of heparin has been reported by other authors [19, 20], and is one of the reasons why prophylactic intensity anticoagulation remains the recommended strategy, waiting for the results of ongoing randomized controlled trials [16, 18], even if a higher-intensity anticoagulation can be considered for patients judged to be at high thrombotic and low bleeding risk.

Due to the severe pandemic diffusion, with a large number of patients requiring hospitalization, VTE events were diagnosed only when clinically evident. No systematic tests were performed to exclude asymptomatic DVT. Moreover, we cannot exclude that PE could be the cause of fatal outcome in patients with severe respiratory failure, because no systematic autoptic examination was performed.

We acknowledge the limitations of our study. Firstly, it is a retrospective observational study, and the treatment used are in line with the local practice, without any indication by the study protocol. The study was designed to evaluate the type and dosage of heparin used, therefore the availability of data is high. However, the wide range of dosages used, imposes to analyze patients in two groups that include different dosages. Moreover, the severity of patients enrolled may be influenced by the availability of ICU beds that could have limited the number of patients who received mechanical ventilation. Strength of the study are the multicentric design, and the accuracy and completeness of follow-up for all patients enrolled.

In conclusion, our data confirmed the high mortality rate of hospitalized patients affected by COVID-19 infection, even when the presentation of the disease was moderately severe leading to admission to general wards. Risk factors for fatal outcome were older age, associated POAD and neurological disease. Treatment with antithrombotic drugs was significantly associated with a 60% reduction of mortality rates. Patients who received sub therapeutic/ therapeutic dosages showed a significantly higher bleeding risk.

References

Grasselli G, Greco M, Zanella A, Albano G, Antonelli M, Bellani G, Bonanomi E, Cabrini L, Carlesso E, Castelli G, Cattaneo S, Cereda D, Colombo S, Coluccello A, Crescini G, Forastieri Molinari A, Foti G, Fumagalli R, Iotti GA, Langer T, Latronico N, Lorini FL, Mojoli F, Natalini G, Pessina CM, Ranieri VM, Rech R, Scudeller L, Rosano A, Storti E, Thompson BT, Tirani M, Villani PG, Pesenti A, Cecconi M, Network C-LI (2020) Risk factors associated with mortality among patients with COVID-19 in intensive care units in Lombardy, Italy. JAMA Intern Med 180:1345–1355

Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z (2020) Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost 18:844–847

Klok FA, Kruip M, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers D, Kant KM, Kaptein FHJ, van Paassen J, Stals MAM, Huisman MV, Endeman H (2020) Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res 191:145–147

Pizzi R, Gini G, Caiano L, Castelli B, Dotan N, Magni F, Virano A, Roveda A, Bertù L, Ageno W (2020) Coagulation parameters and venous thromboembolism in patients with and without COVID-19 admitted to the Emergency Department for acute respiratory insufficiency. Thromb Res 196:209–212

Giusti B, Gori AM, Alessi M, Rogolino A, Lotti E, Poli D, Sticchi E, Bartoloni A, Morettini A, Nozzoli C, Peris A, Pieralli F, Poggesi L, Marchionni N, Marcucci R (2020) Sars-CoV-2 induced coagulopathy and prognosis in hospitalized patients: a snapshot from Italy. Thromb Haemost 120:1233–1236

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B (2020) Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 395:1054–1062

Giacomelli A, Ridolfo AL, Milazzo L, Oreni L, Bernacchia D, Siano M, Bonazzetti C, Covizzi A, Schiuma M, Passerini M, Piscaglia M, Coen M, Gubertini G, Rizzardini G, Cogliati C, Brambilla AM, Colombo R, Castelli A, Rech R, Riva A, Torre A, Meroni L, Rusconi S, Antinori S, Galli M (2020) 30-Day mortality in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 during the first wave of the Italian epidemic: a prospective cohort study. Pharmacol Res 158:104931

Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J, Rajagopalan H, O’Donnell L, Chernyak Y, Tobin KA, Cerfolio RJ, Francois F, Horwitz LI (2020) Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ 369:m1966

Tamara A, Tahapary DL (2020) Obesity as a predictor for a poor prognosis of COVID-19: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Syndr 14:655–659

Zheng Z, Peng F, Xu B, Zhao J, Liu H, Peng J, Li Q, Jiang C, Zhou Y, Liu S, Ye C, Zhang P, Xing Y, Guo H, Tang W (2020) Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Infect 81:e16–e25

Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, Jacobson SD, Meyer BJ, Balough EM, Aaron JG, Claassen J, Rabbani LE, Hastie J, Hochman BR, Salazar-Schicchi J, Yip NH, Brodie D, O’Donnell MR (2020) Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 395:1763–1770

Goshua G, Pine AB, Meizlish ML, Chang CH, Zhang H, Bahel P, Baluha A, Bar N, Bona RD, Burns AJ, Dela Cruz CS, Dumont A, Halene S, Hwa J, Koff J, Menninger H, Neparidze N, Price C, Siner JM, Tormey C, Rinder HM, Chun HJ, Lee AI (2020) Endotheliopathy in COVID-19-associated coagulopathy: evidence from a single-centre, cross-sectional study. Lancet Haematol 7:e575–e582

Al-Samkari H, Karp Leaf RS, Dzik WH, Carlson JCT, Fogerty AE, Waheed A, Goodarzi K, Bendapudi PK, Bornikova L, Gupta S, Leaf DE, Kuter DJ, Rosovsky RP (2020) COVID-19 and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Blood 136:489–500

Moores LK, Tritschler T, Brosnahan S, Carrier M, Collen JF, Doerschug K, Holley AB, Jimenez D, Le Gal G, Rali P, Wells P (2020) Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of VTE in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 158:1143–1163

Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, Chuich T, Dreyfus I, Driggin E, Nigoghossian C, Ageno W, Madjid M, Guo Y, Tang LV, Hu Y, Giri J, Cushman M, Quere I, Dimakakos EP, Gibson CM, Lippi G, Favaloro EJ, Fareed J, Caprini JA, Tafur AJ, Burton JR, Francese DP, Wang EY, Falanga A, McLintock C, Hunt BJ, Spyropoulos AC, Barnes GD, Eikelboom JW, Weinberg I, Schulman S, Carrier M, Piazza G, Beckman JA, Steg PG, Stone GW, Rosenkranz S, Goldhaber SZ, Parikh SA, Monreal M, Krumholz HM, Konstantinides SV, Weitz JI, Lip GYH, Global Covid-19 Thrombosis Collaborative Group EBTINE, the Iua SBTESCWGOPC and Right Ventricular F (2020) COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 75:2950–2973

Cuker A, Tseng EK, Nieuwlaat R, Angchaisuksiri P, Blair C, Dane K, Davila J, DeSancho MT, Diuguid D, Griffin DO, Kahn SR, Klok FA, Lee AI, Neumann I, Pai A, Pai M, Righini M, Sanfilippo KM, Siegal D, Skara M, Touri K, Bou AKLI, Boulos M, Brignardello-Petersen R, Charide R, Chan M, Dearness K, Darzi AJ, Kolb P, Colunga-Lozano LE, Mansour R, Morgano GP, Morsi RZ, Noori A, Piggott T, Qiu Y, Roldan Y, Schunemann F, Stevens A, Solo K, Ventresca M, Wiercioch W, Mustafa RA, Schunemann HJ (2021) American Society of Hematology 2021 guidelines on the use of anticoagulation for thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19. Blood Adv 5:872–888

Marietta M, Ageno W, Artoni A, De Candia E, Gresele P, Marchetti M, Marcucci R, Tripodi A (2020) COVID-19 and haemostasis: a position paper from Italian Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (SISET). Blood Transfus 18:167–169

Spyropoulos AC, Levy JH, Ageno W, Connors JM, Hunt BJ, Iba T, Levi M, Samama CM, Thachil J, Giannis D, Douketis JD, Subcommittee on Perioperative CCTHOTSSCOTISOT and Haemostasis (2020) Scientific and standardization committee communication: Clinical guidance on the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost 18:1859–1865

Nadkarni GN, Lala A, Bagiella E, Chang HL, Moreno PR, Pujadas E, Arvind V, Bose S, Charney AW, Chen MD, Cordon-Cardo C, Dunn AS, Farkouh ME, Glicksberg BS, Kia A, Kohli-Seth R, Levin MA, Timsina P, Zhao S, Fayad ZA, Fuster V (2020) Anticoagulation, bleeding, mortality, and pathology in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol 76:1815–1826

Pesavento R, Ceccato D, Pasquetto G, Monticelli J, Leone L, Frigo A, Gorgi D, Postal A, Marchese GM, Cipriani A, Saller A, Sarais C, Criveller P, Gemelli M, Capone F, Fioretto P, Pagano C, Rossato M, Avogaro A, Simioni P, Prandoni P, Vettor R (2020) The hazard of (sub)therapeutic doses of anticoagulants in non-critically ill patients with COVID-19: the Padua province experience. J Thromb Haemost 18:2629–2635

Antonucci E, Poli D, Tosetto A, Pengo V, Tripodi A, Magrini N, Marongiu F, Palareti G, Register S (2015) The Italian START-register on anticoagulation with focus on atrial fibrillation. PLoS ONE 10:e0124719

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42:377–381

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383

Schulman S, Kearon C, Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the S, Standardization Committee of the International Society on T and Haemostasis (2005) Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost 3:692–694

Kaatz S, Ahmad D, Spyropoulos AC, Schulman S, Subcommittee on Control of A (2015) Definition of clinically relevant non-major bleeding in studies of anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolic disease in non-surgical patients: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost 13:2119–2126

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395:497–506

Myers LC, Parodi SM, Escobar GJ, Liu VX (2020) Characteristics of hospitalized adults with COVID-19 in an integrated health care system in California. JAMA 323:2195–2198

Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, Kim R, Jerome KR, Nalla AK, Greninger AL, Pipavath S, Wurfel MM, Evans L, Kritek PA, West TE, Luks A, Gerbino A, Dale CR, Goldman JD, O’Mahony S, Mikacenic C (2020) Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region: case series. N Engl J Med 382:2012–2022

Guan WJ, Liang WH, Zhao Y, Liang HR, Chen ZS, Li YM, Liu XQ, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Ou CQ, Li L, Chen PY, Sang L, Wang W, Li JF, Li CC, Ou LM, Cheng B, Xiong S, Ni ZY, Xiang J, Hu Y, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Cheng LL, Ye F, Li SY, Zheng JP, Zhang NF, Zhong NS, He JX, China Medical Treatment Expert Group for C (2020) Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J 104:e118

Wu P, Hao X, Lau EHY, Wong JY, Leung KSM, Wu JT, Cowling BJ, Leung GM (2020) Real-time tentative assessment of the epidemiological characteristics of novel coronavirus infections in Wuhan, China, as at 22 January 2020. Euro Surveill. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000044

Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, Huang H, Zhang L, Zhou X, Du C, Zhang Y, Song J, Wang S, Chao Y, Yang Z, Xu J, Zhou X, Chen D, Xiong W, Xu L, Zhou F, Jiang J, Bai C, Zheng J, Song Y (2020) Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med 180:934–943

Di Castelnuovo A, Bonaccio M, Costanzo S, Gialluisi A, Antinori A, Berselli N, Blandi L, Bruno R, Cauda R, Guaraldi G, My I, Menicanti L, Parruti G, Patti G, Perlini S, Santilli F, Signorelli C, Stefanini GG, Vergori A, Abdeddaim A, Ageno W, Agodi A, Agostoni P, Aiello L, Al Moghazi S, Aucella F, Barbieri G, Bartoloni A, Bologna C, Bonfanti P, Brancati S, Cacciatore F, Caiano L, Cannata F, Carrozzi L, Cascio A, Cingolani A, Cipollone F, Colomba C, Crisetti A, Crosta F, Danzi GB, D’Ardes D, de Gaetano DK, Di Gennaro F, Di Palma G, Di Tano G, Fantoni M, Filippini T, Fioretto P, Fusco FM, Gentile I, Grisafi L, Guarnieri G, Landi F, Larizza G, Leone A, Maccagni G, Maccarella S, Mapelli M, Maragna R, Marcucci R, Maresca G, Marotta C, Marra L, Mastroianni F, Mengozzi A, Menichetti F, Milic J, Murri R, Montineri A, Mussinelli R, Mussini C, Musso M, Odone A, Olivieri M, Pasi E, Petri F, Pinchera B, Pivato CA, Pizzi R, Poletti V, Raffaelli F, Ravaglia C, Righetti G, Rognoni A, Rossato M, Rossi M, Sabena A, Salinaro F, Sangiovanni V, Sanrocco C, Scarafino A, Scorzolini L, Sgariglia R, Simeone PG, Spinoni E, Torti C, Trecarichi EM, Vezzani F, Veronesi G, Vettor R, Vianello A, Vinceti M, De Caterina R, Iacoviello L, RISk CO- and Treatments C (2020) Common cardiovascular risk factors and in-hospital mortality in 3,894 patients with COVID-19: survival analysis and machine learning-based findings from the multicentre Italian CORIST Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 30:1899–1913

Acknowledgements

The members of the START-COVID Investigators are: Rossella Marcucci, Daniela Poli, SOD Malattie Aterotrombotiche, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria-Careggi, Firenze. Walter Ageno, Giovanna Colombo, UOSD Degenza Breve e Internistica, Centro trombosi Ospedale di Circolo, Varese. Chiara Ambaglio, UOSD SIMT Servizio di Immunoematologia e Medicina Trasfusionale, Ospedale di Treviglio – Caravaggio, ASST Bergamo Ovest, Bergamo. Guido Arpaia, U.O. Medicina Interna Carate Brianza ASST-Vimercate. Giovanni Barillari, SOS di Dipartimento “Malattie Emorragiche e Trombotiche, Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Friuli Centrale, Presidio Ospedaliero Universitario “Santa Maria della Misericordia”. Udine. Giuseppina Bitti, Giuseppe Pio Martino Medicina Interna Ospedale Civile di Fermo, Fermo (Ancona). Eugenio Bucherini, Monica Vastola—SS Az.le di Angiologia Faenza (RA) AUSL Romagna. Antonio Chistolini, Alessandra Serrao, Dipartimento di Medicina Traslazionale e di Precisione, Sapienza Università di Roma. Egidio De Gaudenzi, SOC Medicina Interna Ospedale San Biagio – Domodossola. Valeria De Micheli, Ambulatorio Emostasi—Azienda Ospedaliera Di Lecco. Anna Falanga, Teresa Lerede, Luca Barcella, Laura Russo,USC SIMT, Centro Emostasi e Trombosi, Ospedale Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo. Vittorio Fregoni, U.O.C. Medicina Generale, ASST Valtellina e Alto Lario Ospedale di Sondalo. Silvia Galliazzo, UOC Medicina Generale, Ospedale San Valentino, Montebelluna (TV). Alberto Gandolfo , Gianni Biolo, Valentina Trapletti, SC (UCO) Clinica Medica, Azienda sanitaria universitaria Giuliano Isontina (ASU GI)—Ospedale di Cattinara, Trieste. Giorgio Ghigliotti, Clinica Delle Malattie Dell'apparato Cardiovascolare Policlinico San Martino Genova. Elisa Grifoni, Luca Masotti, Medicina Interna 2, Ospedale San Giuseppe , Empoli (Fi). Egidio Imbalzano, UOC Medicina Interna, Policlinico di Messina. Gianfranco Lessiani, Unità Angiologica, Dipartimento di Medicina e Geriatria, Ospedale "Villa Serena", Città Sant'Angelo, Pescara. Niccolò Marchionni, SOD Cardiologia Generale, dipartimento Cardiotoracovascolare, AOU Careggi, Firenze. Giuliana Martini, Sara Merelli, Nicola Portesi Centro Emostasi, Spedali Civili Di Brescia, Franco Mastroianni, Giovanni Larizza, UOC Medicina Interna, Covid Unit, EE Ospedale Generale F. Miulli, Acquaviva delle Fonti (Ba). Carlo Nozzoli, SOD Medicina Interna 1, Dipartimento di Emergenza AOU- Careggi , Firenze. Serena Panarello, Chiara Fioravanti, SC Medicina Interna, EO Galliera, Genova. Simona Pedrini, Federica Bertola, Servizio di Laboratorio, Istituto Ospedaliero Fondazione Poliambulanza, Brescia. Raffaele Pesavento, Davide Ceccato UO Clinica Medica 3 Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Padova. Filippo Pieralli, SOD Medicina Interna ad alta intensità, Dipartimento di Emergenza , AOU- Careggi, Firenze. Pasquale Pignatelli, Daniele Pastori, Centro Trombosi, Clinica Medica I, Università La Sapienza Roma. Paola Preti, Centro Emostasi e Trombosi Medicina Generale II, IRCCS Fondazione Policlinico S. Matteo, Pavia. Elias Romano, Alessandro Morettini, Medicina Interna 2, Dipartimento di Emergenza, AOU-Careggi Firenze. Girolamo Sala, Fabrizio Foieni, Michela Provisone, UOC Medicina II, Ospedale di Circolo Busto Arsizio (Va). Luca Sarti, Antonella Caronna, Struttura complessa di medicina interna ed area critica, Ospedale di Baggiovara (Mo). Federico Simonetti, Ilaria Bertaggia, UOC Ematologia Aziendale – Ospedale Versilia –Lido di Camaiore (Lucca). Piera Sivera, Carmen Fava, S.C.D.U. Ematologia e terapie cellulari, AO Ordine Mauriziano Umberto 1° Torino. Viviana Scancassani, ASST Valtellina UOC di Medicina Sondrio. Michele Spinicci, Alessio Bartoloni, SOD Malattie Infettive e Tropicali, AOU Careggi, Firenze. Adriana Visonà, Beniamino Zalunardo, UOC Angiologia, Ospedale San Giacomo Apostolo , Castelfranco Veneto (Treviso). Sabina Villalta, UOC Medicina Generale, Ospedale San Giacomo Apostolo, Castelfranco Veneto (Treviso).

Funding

The “Arianna Anticoagulazione” Foundation (Bologna Italy) supported the study. The Foundation has received an unrestricted research grant from Italfarmaco (Milan, Italy), specifically dedicated to the realization of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

DP, WA, RM designed the study, collected data; DP analysed and interpreted data and drafted the manuscript. EA analysed and and interpreted data drafted the manuscript. START COVID Investigators contributed to the data collection. WA, PP and GP revised the draft of the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and finally approved the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

All patients enrolled in the study have read and signed the informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The members of the START-COVID Investigators are mentioned in “Acknowledgement” section.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Poli, D., Antonucci, E., Ageno, W. et al. Low in-hospital mortality rate in patients with COVID-19 receiving thromboprophylaxis: data from the multicentre observational START-COVID Register. Intern Emerg Med 17, 1013–1021 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-021-02891-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-021-02891-w