Abstract

Over the past 50 years, the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection has fallen as standards of living improved. The changes in the prevalence of infection and its manifestations (peptic ulcer disease and gastric mucosal lesions) were investigated in a large cohort of Sardinians undergoing upper endoscopy for dyspepsia. A retrospective observational study was conducted involving patients undergoing endoscopy for dyspepsia from 1995 to 2013. H. pylori status was assessed by histology plus the rapid urease test or 13C-UBT. Gastric mucosal lesions were evaluated histologically. Data including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) use and the presence of peptic ulcers were collected. The prevalence of H. pylori was calculated for each quartile and for each birth cohort from 1910 to 2000. 11,202 records were retrieved for the analysis (62.9 % women). The overall prevalence of H. pylori infection was 43.8 % (M: 46.6 % vs. F: 42.0 %; P = 0.0001). A dramatic decrease in the prevalence of infection occurred over the 19-year observation period. The birth cohort effect was evident in each category (quartile) reflecting the continuous decline in H. pylori acquisition. Over time, the prevalence of peptic ulcers also declined, resulting in an increase in the proportion of H. pylori negative/NSAID positive and H. pylori negative/NSAID negative peptic ulcers. The prevalence of gastric mucosal changes also declined despite aging. The decline in H. pylori prevalence over time likely reflects the improvement in socioeconomic conditions in Sardinia such that H. pylori infection and its clinical outcomes including peptic ulcer are becoming less frequent even among dyspeptic patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori infects almost 50 % of the world’s population with the prevalence being highest in developing countries [1]. Low socioeconomic status, poor sanitation, unclean water supplies, density of housing, overcrowding, number of siblings, sharing a bed and living in rural areas are all risk factors for the acquisition of an H. pylori infection [2]. The infection is typically acquired in childhood with the majority of children becoming infected before the age of ten, with the prevalence rising up to 80 % or greater in developing countries [3].

The prevalence of the infection increases with age, which is thought to reflect a birth cohort phenomenon related to a decline in the rate of H. pylori acquisition during childhood in recent years [4]. However, even within a community, acquisition is more likely among lower socioeconomic groups as reflected in an increased incidence in blacks and Hispanics in the US and shepherds in Sardinia [1–3, 5]. Such differences have been attributed to different socioeconomic factors, life style, sanitation practices and possibly direct contact with some animals [1, 3–5]. Within a particular country, a change in the prevalence of H. pylori generally correlates to changes in standards of living and sanitary practices. In Japan, for example, it has been reported that 70 to 80 % of adults born before 1950, 45 % of those born between 1950 and 1960, and 25 % of those born between 1960 and 1970 are infected [6]. This rapid decline of infection has been attributed to Japan’s post-war economic progress and improvements in sanitation [6].

H. pylori infection is a major cause of gastroduodenal diseases. Infected individuals develop chronic active gastritis or follicular gastritis that can progress to intestinal metaplasia, atrophy, dysplasia and gastric cancer. H. pylori-associated peptic ulcer and gastric cancer often present with dyspepsia. However, dyspeptic symptoms occur frequently in the adult population, and despite the fall in H. pylori prevalence, remain a major indication for endoscopy [7, 8]. The aim of this study was to analyze the prevalence trend of H. pylori infection and peptic ulcer disease in patients who underwent upper endoscopy for dyspeptic symptoms during the period when the prevalence of H. pylori was rapidly falling.

Methods

Patient selection

This was a retrospective single-center study. Charts of patient with dyspeptic symptoms who underwent upper endoscopy from January 1995 to December 2013 at an open access Digestive Endoscopy Service, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Sassari, Italy, were retrieved from the computerized Endoscopy Reporting System. Each patient had been interviewed by a Gastroenterologist. Dyspeptic symptoms included: epigastric pain, upper abdominal discomfort, early satiety, nausea and vomiting. Demographic information such as age, gender, marital status, place of residence, smoking habit, and occupation was recorded as well as all medications taken in the previous 2 months prior to esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD).

Exclusion criteria

Patients that underwent upper endoscopy for other reasons such as cirrhosis follow-up, suspect celiac diseases, reflux diseases, alarm symptoms or other indications were not included. Exclusions also included absence of all 4 gastric biopsies, unknown H. pylori status, acute ulcer bleeding, significant liver disease or prior treatment for H. pylori infection. For patients who underwent multiple EGDs within the given time period, only results from the first test were included.

Diagnostic methods

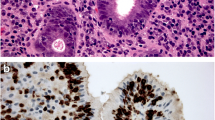

Endoscopic findings and histologic examinations were entered in a computerized system for analysis. Diagnosis of peptic ulcer was based on the endoscopic detection of the typical ulcer crater in the stomach or duodenum of 0.5 cm or larger in diameter. For each patient, at least four gastric biopsy specimens were taken: two from the antrum, one from the angulus, and one from the corpus of the stomach. Biopsy specimens for histology were fixed immediately in 10 % buffered formalin and stained with hematoxylin–eosin and Giemsa stains to grade the density of H. pylori. Morphology was assessed by an expert GI-pathologist. Infiltration of the stomach with polymorphonuclear cells (active inflammation), and with mononuclear inflammatory cells (chronic inflammation), was defined active or chronic gastritis. An aggregate of lymphocytes with a germinal center and lymphoid aggregates as accumulations of lymphocytes and plasma cells without a germinal center was defined as a lymphoid follicle; the presence of several lymphoid follicles was designated as follicular gastritis.

Intestinal metaplasia was defined as the replacement of normal differentiated gastric mucosa by mucosa histologically similar to normal intestinal epithelium. Atrophy was defined as loss of the appropriate glands from the site of the biopsy.

H. pylori status

H. pylori infection was defined by at least two tests: presence of H. pylori on histological examination of gastric biopsies and detection of a positive rapid urease test or 13C-UBT positivity. One biopsy from the antrum was placed immediately into a 6 % urea solution for a rapid urease test (RUT) (CP-test; Yamanouchi S.p.A., Milan, Italy). A positive result was recorded for a color change from yellow to pink within 24 h. The 13C-UBT was performed according to a standardized protocol, the sensitivity and specificity of which have been reported to be of 95 % [9]. All breath tests were analyzed at the same laboratory using a single gas isotope ratio mass spectrometer (ABCA, Europe Scientific, Crewe, UK).

Ethical considerations

An Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the local ethics committee (Prot N° 2099/CE, 2014).

Statistical analysis

Patients were considered positive for H. pylori when the micro-organism was detected in at least one gastric biopsy, or by 13C-UBT- or RUT-positivity. Active gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, follicular gastritis and atrophy were reported as present if they were observed in at least one biopsy irrespective of the site.

Categorization of socioeconomic status was based on the occupation [10]. Five categories were identified: I, professionals (i.e., graduated from university); II, technical and administrators (i.e., not graduated from university); III, clerks and sales technicians; IV, semiskilled and unskilled workers, and uneducated farmers. High-risk categories included occupations known to be at higher risk for the acquisition of infection such as shepherds, abattoirs, veterinarians and nurses [1, 11, 12].

The association between each independent variable in the study and the prevalence of H. pylori infection was tested by Mantel–Haenszel Chi Square test, calculating age-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and their 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CIs).

A multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of known risk factors on the susceptibility to acquire H. pylori infection after controlling for the potential confounding effect of covariates. Hosmer–Lemeshow statistics were used to assess model fit. For each covariate, the odds ratio and 95 % CI are reported. Significance level of P < 0.05 was set for all calculations. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 16.0 for Windows (Chicago, IL).

Results

Prevalence of H. pylori infection in relation to the study variables

A total of 12,749 patient charts were retrieved, of whom 11,202 were valid for analysis. Patients with unknown H. pylori status or an incomplete set (four) of biopsies were excluded from the study (1525) plus 22 patients from Africa and China. All patients were Caucasian from North Sardinia, 7042 (62.9 %) were females. The overall prevalence of H. pylori infection was 43.8 %, and slightly, but significantly higher among males than females (i.e., 46.6 vs. 42.0 %; OR 1.20, 95 % CI 1.11–1.29, P = 0.0001) (Table 1).

We classified the overall study period into four time periods: 1995–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009, and 2010–2013. There was a significant decline in the prevalence of the infection from the first to the last period (Table 1). Studied patients between the years 2010 and 2013 had consistently lower odds ratio of H. pylori infection than those between 1995 and 1999 (25.6 vs. 64 %, respectively, OR 0.19, 95 % CI 0.17–0.21, P < 0.0001). There was no difference in the H. pylori prevalence in relation to smoking habits (Table 1). The prevalence of H. pylori was significantly higher in socioeconomic categories III (48 %), IV (42 %) and high-risk group (50 %) compared to categories I (37 %) and II (41 %), the difference remained significant after adjusting for age and gender (Table 1). In the multiple logistic regression analysis only age and time intervals remained significant predictors of H. pylori infection (P < 0.0001), whereas all other covariates resulted non-significant (Table 2).

Changing pattern of the prevalence of H. pylori infection and associated diseases by time

We examined the changing pattern of infection. H. pylori prevalence was compared among the four studied group for each birth cohort; patients who were tested between 1995–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009, and 2010–2013. There was a dramatic decrease in H. pylori infection prevalence over the 19-year studied period and that drop was the most significant among the oldest patients (Table 3).

When we examined the pattern of intestinal metaplasia, follicular gastritis, dysplasia, and atrophy among the same four studied cohorts, we find that there is a falling pattern of these conditions although it is not linear (Table 4). Moreover, among H. pylori positive patients, the prevalence of intestinal metaplasia is significantly higher in the older cohorts (Table 5).

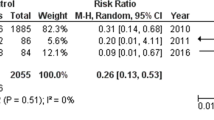

Peptic ulcer disease

The most common clinical manifestations of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs NSAID-related GI damage to tissue are a combination of gastroduodenal erosions and ulcerations, often called NSAID-induced gastropathy, affecting 25–50 % of chronic NSAID users [13–15]. In addition, H. pylori infection and (NSAIDs) use independently increase the risk for the development of peptic ulcer disease [16]. Therefore, we compared the distribution of peptic ulcer/erosions by birth cohort among NSAID users and non-users. A relationship between the prevalence of peptic ulcer/erosion was demonstrated in patients receiving NSAIDs among each cohort (Fig. 1). In H. pylori negative patients, the risk of having peptic ulcer/erosions among those taking NSAIDs is nearly two times greater than among those not taking NSAIDs (16.5 vs. 10 %, respectively, (OR 1.74, 95 % CI 1.38–2.19; P < 0.0001). Considering peptic ulcer alone the ORs are 5.5 times higher among H. pylori positive patients taking NSAIDs compared with H. pylori negative patients not taking NSAIDs (Table 6).

We examined the distribution of non-complicated peptic ulcer in dyspeptic patients for each time period. There is a decline in the prevalence of ulcers over time, while the prevalence of H. pylori negative ulcers or for NSAIDs use increases from 12 % in 1996–1999 to 40.7 % in 2009–2013 (Fig. 2).

Discussion

This study investigated the epidemiology of H. pylori infection and peptic ulcer disease among Italian dyspeptic patients residing in the same geographic area. Our large sample size allowed comparisons within and among birth cohorts and among those with different risks for H. pylori acquisition. The prevalence of H. pylori and its sequelae decreased over the study period. These changes in prevalence of the infection are consistent with the presence of birth cohorts that differ in risk (i.e., persons born before 1950 have a notably higher rate of infection than people born afterwards), reflecting a change in the rate of acquisition of the infection in childhood. The results of the present study suggest that the rate of acquisition of H. pylori infections has been falling in Sardinia since at least 1950. In the first half of the twentieth century, Sardinia was considered an underdeveloped region compared to the rest of Italy [17]. Sardinia recovered slowly after World War II, yet benefited from the dramatic economic and social advancements on the mainland [17]. In 1952, approximately 45 % of the Sardinian population still earned their livelihood in agriculture and animal farming vs. only 28 % in industry (in 1936 the percentages were 57 and 20 %, respectively) [17]. Improvements in sanitary conditions and clean public water system were also introduced in Sardinia in the 1950s.

Our study shows that the prevalence of H. pylori infection among those born between 1980s and 2000 ranges from 18 to 12 %. This change reflects the changes in sanitation and socioeconomic factors as higher standards of living, increasing education, and improved sanitation have all been associated with a lower prevalence of H. pylori infection [1–3].

The prevalence of dyspepsia as an indication for endoscopy also differs in relation to the socioeconomic status with a higher rate of infection in the lower social classes. Although univariate statistical analysis shows that the prevalence of H. pylori infection is mostly influenced by low socioeconomic status, male gender and old age, only the latter remains strongly significant in the multivariate logistic regression model. The multivariate analysis also supports a significant decrease of H. pylori prevalence in recent years.

The natural history of H. pylori gastritis is for the inflamed area to extend from the antrum into the corpus resulting in a reduction of acid secretion, and eventual loss of parietal cells and development of atrophy. The rate of progression to atrophy varies in different geographic regions related to other environmental factors; diet is one of the most important. Our study shows a high prevalence of atrophy or intestinal metaplasia, or dysplasia that tends to increase with the aging of the different birth cohorts. However, over time, the proportion with atrophic changes decreases. In patients with an active infection, the proportion with metaplasia is also significantly higher in the older cohorts. Our study shows a high prevalence of gastric mucosal changes that tend to increase with the aging of the different birth cohorts.

H. pylori infection and use of NSAIDs are the major causes of peptic ulcers [13–16]. As the frequency of H. pylori infection declines, the use of NSAIDs becomes responsible for an increased percentage of peptic ulcers. Our results confirm that the two risk factors combined (H. pylori infection plus NSAIDs use) increase the risk of developing peptic ulcer approximately fivefold. We also confirm that H. pylori infection and NSAIDs use independently and significantly increase the risk for peptic ulcer. Surprisingly, very high prevalence rates, in the range of 10–40 % of idiopathic ulcer, are observed in this cohort of Sardinian dyspeptic patients. These results are dramatically different from data reported by other Italian Authors where the prevalence for idiopathic peptic ulcer is 4 % [18]. However, in the 1990s, several studies report that idiopathic ulcers comprise 20–40 % of all peptic ulcers in North American countries [19, 20]. It could be speculated that the different genetic Sardinian background compared to the rest of the Italian people may explain the high prevalence of idiopathic ulcer.

Some limitations must be considered. Classification of the socioeconomic classes in our study was based on a single factor, the occupation of the patient, rather than a scale of combined factors, such as years of schooling, income, ownership of property and the occupation of the head of the household during childhood that represents the major lifestyle indicator of the family [1–3]. In addition, this was a retrospective cohort, and has shortcomings such as lack of detailed data regarding several risk factors that are known to be associated with the acquisition of H. pylori infections such as crowded living conditions, number of persons living in the household, the size of the home, whether the patient shared a bed in childhood, and the presence or absence of hot running water, a refrigerator, a toilet inside the home and exposure to animals. However, results of the present study reflect in general the lifestyle, hygiene conditions and cultural background of Sardinians in the last century.

In conclusion, the decline in H. pylori prevalence in patients born in the 1960s reflects the major socioeconomic changes that have occurred in Sardinia in this period of time. The outcome of these changes is that H. pylori infection and its clinical outcomes such as peptic ulcer disease have become an increasing less frequent cause of dyspeptic patients.

References

Kikuchi S, Dore MP (2005) Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 10(Suppl 1):1–4

Dore MP, Malaty HM, Graham DY, Fanciulli G, Delitala G, Realdi G (2002) Risk factors associated with Helicobacter pylori infection among children in a defined geographic area. Clin Infect Dis 35:240–245

Malaty HM (2007) Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 21:205–214

Parsonnet J (1995) The incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 9(Suppl 2):45

Dore MP, Bilotta M, Vaira D et al (1999) High prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in shepherds. Dig Dis Sci 44:1161–1164

Asaka M, Kimura T, Kudo M et al (1992) Relationship of Helicobacter pylori to serum pepsinogens in an asymptomatic Japanese population. Gastroenterology 102:760–766

Talley NJ (2005) American Gastroenterological Association American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 129:1753–1755

Zullo A, Hassan C, De Francesco V et al (2014) Helicobacter pylori and functional dyspepsia: an unsolved issue? World J Gastroenterol 20:8957–8963

Dominguez-Munoz JE, Leodolter A, Sauerbruch T, Malfertheiner P (1997) A citric acid solution is an optimal test drink in the 13C-urea breath test for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut 40:459–462

Dore MP, Bilotta M, Malaty HM et al (2000) Diabetes mellitus and Helicobacter pylori infection. Nutrition 16:407–410

Dore MP, Vaira D (2003) Sheep rearing and Helicobacter pylori infection—an epidemiological model of anthropozoonosis. Dig Dis Sci 35:7–9

Vaira D, D’Anastasio C, Holton J et al (1988) Campylobacter pylori in abattoir workers: is it a zoonosis? Lancet 2:725–726

Davies NM, Wallace JL (1997) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastrointestinal toxicity: new insights into an old problem. J Gastroenterol 32:127–133

Richy F, Bruyere O, Ethgen O et al (2004) Time dependent risk of gastrointestinal complications induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use: a consensus statement using a meta-analytic approach. Ann Rheum Dis 63:759

Tamura A, Murakami K, Kadota J, OITA-GF Study Investigators (2011) Prevalence and independent factors for gastroduodenal ulcers/erosions in asymptomatic patients taking low-dose aspirin and gastroprotective agents: the OITA-GF study. QJM 104:133–139

Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Hunt RH (2002) Role of Helicobacter pylori infection and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in peptic-ulcer disease: a meta-analysis. Lancet 359:14–22

Pes GM, Tolu F, Dore MP et al (2014) Male longevity in Sardinia. A review of historical sources supporting a causal link with dietary factors. Eur J Clin Nutr. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2014.230

Peterson WL, Ciociola AA, Sykes DL et al (1996) Ranitidine bismuth citrate plus clarithromycin is effective for healing duodenal ulcers, eradicating H. pylori and reducing ulcer recurrence. RBC H. pylori Study Group. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 10:251–261

Jyotheeswaran S, Shah AN, Jin HO et al (1998) Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer patients in greater Rochester, NY: is empirical triple therapy justified? Am J Gastroenterol 93:574–578

Ciociola AA, McSorley DJ, Turner K et al (1999) Helicobacter pylori infection rates in duodenal ulcer patients in the United States may be lower than previously estimated. Am J Gastroenterol 94:1834–1840

Acknowledgments

Dr. Graham is supported in part by the Office of Research and Development Medical Research Service Department of Veterans Affairs, Public Health Service grants R01 DK062813 and DK56338 which funds the Texas Medical Center Digestive Diseases Center. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the VA or NIH.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Graham is an unpaid consultant for Novartis in relation to vaccine development for treatment or prevention of H. pylori infection. Dr. Graham is a paid consultant for Red Hill Biopharma regarding novel H. pylori therapies, and has received research support for culture of H. pylori. He is a consultant for Otsuka Pharmaceuticals regarding diagnostic breath testing. Dr. Graham has received royalties from Baylor College of Medicine patents covering materials related to 13C-urea breath test.

Statement of human and animal rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the author.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dore, M.P., Marras, G., Rocchi, C. et al. Changing prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and peptic ulcer among dyspeptic Sardinian patients. Intern Emerg Med 10, 787–794 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-015-1218-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-015-1218-4