Abstract

This paper provides new evidence on the geography of literacy rates in pre-unitary Italy. I provide direct estimates based on a novel and balanced random sample of marriage certificates in 1815. The new figures are disaggregated by gender, area, and skill levels, and are compared to the relevant alternative estimates available. Literacy rates are generally low, and North versus South difference in 1815 literacy was as low as 13.7 percentage points, with the Southern literacy rate of about 50% that of Northern Italy. The North–South gap is much smaller for women than for men, and the average female literacy rate across Italy is a lower 9%. Literacy rates in Central Italy were almost identical to that of Southern Italy, arguably because the schooling systems of Central and Southern Italy were more elitist than the Northern Italian one. This evidence suggests that, although partially present also before 1815, the wide magnitude of North–South gaps in literacy which characterized the country on the eve of the political unification (1861) originated after the Napoleonic period. Primary school centralization reforms might have helped women to rapidly improve literacy rates, leading to a first, regionally unequal, ‘Silent Revolution’ (Cappelli and Vasta in Cliometrica 15:1–27, 2020a).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Traditional views of nineteenth-century Italian economic history consider the country before the Unification as a land of widespread illiteracy and unskilled agricultural labor, especially in the South.Footnote 1 Economic historians have provided convincing evidence that in terms of economic performance and living standards, Italy was already characterized by a significant dualism at the time of the Unification, whether measuring it through real wages (Federico et al. 2019a, b; Malanima and Daniele 2007), life expectancies and heights (A’Hearn and Vecchi 2017), social capital and culture (Putnam et al. 1994), GDP (Felice 2014; Malanima and Daniele 2007; Daniele and Malanima 2011), Human Development Index (Felice and Vasta 2015), or income inequality (Felice 2019).Footnote 2

The first unitary census already showed evident North–South literacy gaps: in 1861, the census literacy rates were 27.28% in the North, 17.19% in the Centre, and 10.14% in the South (MAIC 1866b, XXII–XXV). Literacy rates have proved important in explaining the evolution of key economic parameters after the Unification (manufacturing: Basile and Ciccarelli 2018; schooling: Cappelli and Quiroga Valle 2020; labor productivity: Ciccarelli and Fachin 2017; rate of invention: Nuvolari and Vasta 2017; real wages: Federico et al. 2019a, b). But the lack of systematic data for the period before the political unification (1861) makes it difficult to attribute the role of specific events to the origins of the Italian regional divides. Gathering evidence on the origins of the divides would also be important to understand the nature of the underlying mechanisms of further divergence.

A conventionally held view is that from the mid-eighteenth century onward, Italian absolutist rulers attempted, with some success, to start institutional reforms inspired by the Enlightenment, and that Napoleon built upon their efforts by initiating a process of economic growth (Dincecco and Federico 2021). Nonetheless, the cost of French dominance to Italian states in terms of taxes, trade, and potentially even military conscription was high (Dincecco et al. 2011). This brings into light the question of whether the benefits of institutional reforms outweighed the costs. Dincecco and Federico (2021, 23) suggest that the Napoleonic reforms were important to ‘clear out the institutional undergrowth left over from the Ancien Régime, but that they were not in themselves enough to provide Italy with modern growth-enhancing institutions’ and that the real turning point was the reforms enacted in Piedmont after the military defeat by Austria in 1848–49 and later extended to the rest of Italy. Other studies have attributed an important role for the origin of literacy divides in the late eighteenth-century to the Habsburg Austrian institutional reforms in the Northern region of Lombardy (Toscani 1993), or to the different responses to public schooling reforms after the Restoration of 1815 (Lupo 2005, 141–175), or to the particularly conservative reaction of the Bourbons in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies after the various insurrections of 1820–21, 1830–31, and especially of 1848 (Felice 2013, 30–38). In this respect, Postigliola and Rota (2020, 2021) document a significant effect of the duration of the French period—longer in Northern Italy than in Southern Italy—on 1861 literacy rates obtained from unitary censuses and on social capital. These explanations are not necessarily in conflict with each other. However, to make advancements in this important debate, there is an urgent need for new systematic data collection efforts aiming at measuring the extent of regional divides before the unification.

In an attempt to overcome the data limitations that pervade pre-unitary Italian sources, this paper offers new and direct estimates about the literacy rates at a crucially important moment in time: right after the first State-driven schooling reforms were enacted in Austrian Lombardy and Borbonic Kingdom of Naples, that is, after the 1770s, but before the Napoleonic educational reforms of the 1802–1815 could show their effects. In this relatively neglected period of Italian history, we can see the premises for the earliest State-driven human capital efforts undertaken in Italy, and related path dependency in later educational and social outcomes.

I offer a systematic account of literacy rates from all the sources that, to my knowledge, are available to comprehensively study literacy rates in pre-unitary Italy. The main data source is a novel and representative cross-sectional sample of 1216 individual-level marriage certificate signatures dating to 1815. I randomly select villages with marriage certificates in the Antenati (www.antenati.san.beniculturali.it) online genealogical archives following Schofield (1973), who, 50 years ago, first attempted to scale up the literacy information gathered from more than 200 local parishes to the level of England. Antenati gathers birth, death, and marriage records from Italian State archives. The sample (henceforth ‘Antenati’ sample) is constructed to have representative literacy rates at the level of Italian provinces, regions and macroarea (North, Centre, and South), similarly to Rossi et al. (2001) for household budgets and Shaw-Taylor and Wrigley (2014) for occupational structure. I account for under-sampling issues with weighting and regression approaches. This allows for a safely balanced sample that avoids the underrepresentation of some areas, which also divides the literacy rates of each area into three main occupational sectors (services, industry, and agriculture). From marriage certificates, I collect information about the ability to sign of spouses, but also about their occupations, and about parents’ occupations. As an additional step, I collect further data from selected parts of Italy. The first is a novel dataset containing all the available signatures, rather than a sample thereof, for a large area of the provinces of Udine, Salerno, and Abruzzo Ulteriore II. The second is a sample of eighteenth-century marriage signatures (from Processetti matrimoniali) for the city of Naples. I also collect literacy rates from studies who focused on specific parts of Italy in and around 1815 (also referred to as ‘local studies’). Finally, I consider unitary censuses and related secondary literature.Footnote 3

The Antenati sample of signatures across Italy well reconstructs the literacy that was documented by local studies and indirect approaches in the period of interest. The levels of literacy rates are low throughout Italy, and not only in the South. Overall, I find a sizeable North versus South difference in literacy rates of 13.7 percentage points, whereas the previous estimate by Ciccarelli and Weisdorf (2019) was 20 percentage points. However, in terms of levels, the level of literacy in the South was about 47% of the North one. This estimate is similar to Ciccarelli and Weisdorf (2019) since in our estimates, the levels of literacy rates are lower both in the North and in the South. Compared with the previous literature, probably the most important result is the particularly low level of literacy rates of women (9.2%). The wealthiest parts of Southern Italy had particularly high literacy rates: Naples and its province had literacy rates comparable to those of Lombardy in the North. The rich information of marriage certificates also enables us to look at new dimensions of illiteracy. For instance, the urban–rural difference was 18 percentage points and the gender difference was of 22 percentage points for an average male literacy of 31%. The North–South gap was particularly high among peasants, and the literacy rate of Northern Italian peasants was similar to the average literacy in Central and Southern Italy.

This paper contributes to the following streams of research. First, it advances the literature on the schooling system and literacy in Italy through a direct approach to the study of pre-unitary origins of Italian North–South divides. This complements the existing studies that derived information from small areas of Italy or unitary censuses with new and rich individual-level data, which also disaggregate literacy rates by skill levels, at a time when first state-driven educational efforts started.Footnote 4 Second, this study provides an operative methodology to safely derive countrywide estimates of literacy rates from marriage certificates. This is useful for scholars who wish to learn about supply of human capital in other countries at their early stages of industrialization, when often no census data is available (e.g., Meier zu Selhausen et al. 2018; Álvarez and Palencia 2018).Footnote 5 I also corroborate the empirical validity of this exercise with a particularly rich comparison with other sources. Third, by placing the results in the historical context of early nineteenth-century schooling reforms, this paper also indirectly relates to the literature on the role of nineteenth-century school reforms for human capital formation and modern economic growth.Footnote 6

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 introduces the reader to the context of the history Italian education over the period 1770–1861. Section 3 describes the sources. Section 4 describes the research design and discusses its validity. Section 5 presents the main results about literacy rates and places them in context. Section 6 contains a conclusion.

2 The evolution of literacy, 1770–1861: historical background

This section covers a brief history of the educational policies enacted in Italy from the 1770 to 1861 and can be useful for the reader to adequately place the historical results of this paper in context.Footnote 7 Until the 1770s, the absolutist governments of the many Italian states did not conceive education as a state affair. Most schools were privately established where the demand was the highest. In the North, primary schools were demanded especially by small landowners, manufacturers, and the ones in need of skills to emigrate (Toscani 1993). Teaching was catered to individual students rather than classroom-based and teachers were ecclesiastical (Genovesi 2010). The so-called enlightened despots gradually became aware of the importance of economic growth for political legitimacy and military power. Even the government of catholic rulers as Maria Theresa of Habsburg-Teschen reduced the feudal rights (i.e., through taxation), and ecclesiastical privileges (i.e., in education provision). Relatedly, the members of the Company of Jesus were expelled from various European States.

Jesuits had been central providers of higher education in Italy since the foundation of the first Jesuit College in Messina in 1604. In many states, the Jesuits continued to influence the intellectual life even after the expulsion, as in the reformist Habsburg Empire. But the Jesuit expulsion spurred a general tendency to find alternatives to religious education also at the level of primary education. A variety of solutions were offered, including the decision of the Papal State to keep the education entirely in the hands of ecclesiastical teachers; intermediate forms that handed education to lay orders, such as the Scolopi in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany; the first attempts to have a public education system in the Kingdom of Naples of Ferdinand IV of Bourbon and in the Lombardy ruled by emperor Maria Theresa of Habsburg-Teschen. In the Kingdom of Naples, the diffusion of new collective teaching methods (normal schools) and new public primary schools was effective in metropolitan Naples and neighboring areas (Terzi 2001; Zazo 1927), but less so in rest of the kingdom. According to Lupo (2005), the unsuccessful diffusion of primary schools elsewhere in the South was due to insurmountable obstacles posed by local noblemen and clerics (Lupo 2005). This explains the exceptionally high levels of literacy rates in Campania, where Naples is. The reforms enacted under Maria Theresa were also successful in urban centers, but less so in rural centers (Toscani 1993). Importantly, Maria Theresa also suppressed the religious orders to fund public and—ideally—mandatory primary schools. The political government of her descendant Joseph II of Habsburg-Lorena specifically targeted areas with fewer private schools. Toscani (1993) observes that in the agrarian region of Bassa Padana, the schools were now many, but the demand for schooling remained low, as did literacy.

The first phase of French domination (1796–1799) was too short-lived for the invaded states to adopt a consistent set of reforms in line with the revolutionary ideologies, although the French imposed very high tributes to all conquered regions (Dincecco and Federico 2021, 7). The second phase of French domination (1801–1815) saw a gradual incorporation of all countries of pre-unitary Italy, excluding Sicily and Sardinia, to what would soon become the French empire in 1804.Footnote 8 This time, the domination was also political, and was exercised directly by Napoleon Bonaparte, Bonaparte family ties, or close allies. The Napoleonic government introduced radical reforms to various aspects of the civil and administrative system in all the Empire, creating what is sometimes referred to as ‘administrative monarchy’ (Benigno 2014). The reforms came at the cost of higher taxation relative to ancien régimes because it also became necessary to fund the French and Italian military forces (Dincecco and Federico 2021, 7–8). This radical institutional change was also reflected in the design of public schooling policies: from 1802 on, various laws and decrees aimed at centralizing the education around the State, which determined the syllabi, imposed free and mandatory attendance to primary schools, prepared and funded teachers, and directly controlled private, often ecclesiastical, schools. The administrative uniformity of the Napoleonic period implied that the public schooling reforms of the time were eventually imposed throughout continental Italy. And yet Vigo (1971) stressed how only the states that were not under the direct control of Napoleon—the Kingdom of Naples and especially the Cisalpine Republic, which included Lombardy—could have the necessary public autonomy to create a coherent set of legislation that was tailored to the local issues. Yet, in Lombardy public expenditure in schooling varied considerably by department (Piseri 2017, 105–119, 139–142, 222–236). However, in the Kingdom of Naples even the larger autonomy was insufficient: the first set of reforms of 1806 proved to be ineffective until central authorities gained reach over the more remote provinces with the Decreto Organico della Pubblica istruzione.Footnote 9

The most evident effect of these reforms was to centralize and boost public education provision, although with important regional variations. Indeed, institutional centralization did not mean that funding was also completely centralized. The central government only had the duty to inspect the schools, probably because of the crisis of the public finances that followed the collapse of the absolute monarchies. Moreover, while the number of schools increased, this did not necessarily go hand in hand with a shift in the public perception of primary schools as having different features from ‘ancient’ schools, influenced by religious beliefs, local élites, and parental choices.Footnote 10

After the Restoration (1815) every Italian state at least formally reverted to the administrative systems of ancien régimes, with the notable exception of the newly formed Kingdom of Two Sicilies composed of the Kingdom of Naples and the island of Sicily (see Appendix Fig. 9a). Arguably to reduce popular support for revolutionary ideas, taxation was kept low (Dincecco and Federico 2021). As in many other fields such as taxation of land (Felice 2013), the Borbonic king remained idle in terms of creating new primary schools: Gargano (2012) documents a fall in the number of public male schools (from 2498 to 822) and a fall in public female schools (from 1556 to 1142). The number of private schools also saw a decrease. Alternatives to public schools (i.e., evening schools, adult schools) were concretely diffused only after 1861 (Vigo 2017). Meanwhile, the monarchic response to the revolts of 1820–1821 was repressive and gave back a prominent role to the clergy in public education, in line with the conservative attitude that other Italian States had in 1815 (Lupo 2005).

In Northern and Central Italy, except in the Papal State, the role of the State in the public education system was gradually re-introduced. Indeed, the new absolutist governments could not restore the set of the privileges that their aristocratic title or ecclesiastical status entitled them to before the Napoleonic period. As a result, already in 1818, the Austrian Empire had extended the public schooling system to Lombardo-Veneto, for boys and girls alike. In Savoia (today’s Piedmont), the schools remained in the hands of the clergy until the Boncompagni law 1848. The Boncompagni Law re-affirmed the central role of the state in the education system by controlling also private and ecclesiastical schools, and was the steppingstone of the 1859 Casati Law, later imposed in unified Italy. Instead, the legislative efforts of the Bourbons in the South were increasingly dedicated to more élite secondary and higher education, and the response to the 1848 insurgency was again repressive (Lupo et al. 2014).

3 Sources

The main original source of this study are pre-unitary marriage certificates derived from civil records. In Italy, historical civil records are scattered across more than a hundred different archives, making it difficult to conduct comprehensive studies using these sources. However, a government project, Antenati, started to scan civil registration records from the State archives (Antenati 2023). In this study, I transcribe a random sample of scanned certificates from the Antenati genealogical platform. Of the 137 Italian State archives, 85 contain marriage certificates for the period of interest. Of these, 31 are still awaiting digitization, so I considered the certificates from the 54 State archives. The fact that the digitization effort is still ongoing could raise concerns about whether it is not premature to use this source. Yet, most archives with pending digitization are minor ones or sub-branches of larger archives that also contain marriage certificates for their area (i.e., Assisi, Chieti, Pistoia, Massa, Frosinone). The data is structurally unavailable in large areas, either because the certificates do not have signatures (i.e., in Genova) or because marriage certificates are located elsewhere, such as in parishes and civic courts (i.e., Milan, Nuoro).Footnote 11

These instances will not be solved even when the digitization of State archives is complete: even having the full sample from Antenati would not give a fully representative picture of Italy, if only because the entire regions of today’s Latium except the southernmost provinces, Sardinia, Umbria, and the city of Milan are not covered. This raises the possibility that the sample is not representative of Italy as a whole. This would be the case if, for example, the part of Italy not covered by the sample is disproportionately urban or rural, as urban and rural areas are very different in terms of literacy rates. When the composition of covered and non-covered parts of Italy is compared in terms of urban–rural shares in 1815 and literacy rates in 1861, the composition is very similar both in terms of urban–rural shares and of literacy in 1861 (see Tables 8 and 9).Footnote 12 When the composition differs, the composition of the sample is much closer to the overall one than the part of Italy which could not be sampled is. The composition is also similar by macroarea (North, Centre, and South). The resulting North–South gap would have appeared smaller if the sample had been biased upward for Northern Italy and downward for Southern Italy. This evidence provides some reassurance that no significant sampling bias, along these dimensions, exists between or within macroareas. As a further sensitivity check, I looked at how literacy rates change by macroarea if assuming tht the areas not covered in the sample have the same literacy of the bordering provinces covered on Antenati, and the resulting literacy rates are very close to the literacy rates of the Antenati sample (see Table 10). Further research can later be extended to the remaining archives, and the sampling approach presented here serves this purpose, although issues with data preservation make it clear that for some areas there will still be no marriage certificates with signatures in the future (see next section, Figs. 3, and 7 in Appendix 1 for the spatial coverage of the Antenati source).Footnote 13 I will refer to the sample of marriage certificates drawn from this source as the ‘Antenati sample.’ Besides marriage certificates, the paper also uses datasets derived from the published census reports of 1861, 1871, and 1881, and of other official documents.Footnote 14

Marriage certificate from Sciolze, Piedmont (1814). Content: The groom’s name is Raimondo Gambino, born in 20 April 1790 (so he is 24 years old by the day of marriage, the 22 April 1814); his occupation is coltivatore (peasant) and so are his parents. The bride Altina Elisabetta was born in 05 March 1794, so she is 20 years old at marriage. She is a peasant and so are their parents. The witnesses’ names are Giuseppe Maissi, Giorgio Bloccati, Giuseppe Giovanni Stoffa, and Carlo Tommaso Rosso. Only the witnesses could sign

The ability to sign marriage certificates is used as the proxy for literacy rates. The ability to sign can be indicative of functional literacy adjusted to the standards of the early nineteenth-century Italy.Footnote 15 Marriage certificates in Italian civil records also provide information about occupations, ages, and places of residence of spouses, their parents, and of the witnesses. Moreover, the signatures of the spouses in marriage certificates suffer less selection bias than other sources, such as the signatures of witnesses in death records or the signatures of sailors’ boarding certificates (Rediker 1989) because every strata of the population married,Footnote 16 and spouses did not have particular reasons to learn how to sign compared to the rest of the population.

The earliest attempt to measure signature-literacy is probably Sargant (1867), although important examples are also Cipolla (1969) and Schofield (1968). And yet Astoul (1992, 182–185) raised concerns about measuring literacy rates with marriage signatures (le methode ‘Maggiolo’) in the French Midi (see also Fleury and Valmary 1957). His main concern was that often, parish priests were not keeping appropriate track of all marriages and of their signatures.Footnote 17 Poussou (1993, 214–215) also admitted that the results can be erroneous in some parishes and called for a check of the methods by collecting more signatures in specific areas.Footnote 18 Additionally, comparing literacy rates derived from signatures with stated literacies in censuses or conscript literacies may not be legitimate if they measure different dimensions of literacy. In Italy, literacy inferred from marriage records in 1872 matches census self-reported literacy for the 1871 census very closely.Footnote 19 This suggests that the use of marriage certificates for estimating literacy rates is warranted in this particular historical setting. In 1815, Italy was still pre-industrial, and thus being able to read and write was probably less valued as an important skill by the population than when signing was needed to access better occupational positions, as in more industrialized countries. However, even in 1815, the ability to sign accurately predicted the socioeconomic status of spouses (see Figs. 13 and 14 in Appendix 2).Footnote 20

I focus on 1815 also because it is the only year providing us with a comprehensive geographical picture of literacy based on signatures. Indeed, civil registries were abolished in most Central and Northern Italy after 1815. Parish registers regained the responsibility of recording births, deaths, and marriages, as with the status animarum and recorded information according to the Napoleonic format, but the most records are scattered and difficult to access. Civil registrations were instead maintained in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and in the Duchy of Modena and Reggio; for the latter, only remnants of Southern Liguria were digitized before 1860. Civil Registration was also introduced in Sicily in 1820. This short description of the sources covered by Antenati clearly suggests the advantage of focusing on 1815 because this would allow to combine information from Napoleonic records for Central and Northern Italy and Restoration records for Southern Italy. Figure 1 shows an example of a Napoleonic marriage certificate. Only the format of Restoration civil records is standardized and based on a pre-printed format.

I collect Restoration-period records for Southern regions for years as close as possible to 1815 (usually 1816) after the end of the Napoleonic period. For Northern Italy, with only certificates dating back to the Napoleonic period, I collect information that is as close as possible to 1815 (usually 1814) to exclude years where the novelty of the civil registration system may have affected the number of certificates, and to have a sample with comparable years. Excluding second marriages, the mean age in the sample is 26.76 years old for grooms and 23.25 years old for brides, in line with Rettaroli (1990).

4 Research design

4.1 Sampling strategy

I adopt a clustered random sampling scheme (Som 2020, 115–124). The clusters are ‘villages.’ Villages are often municipalities, but in some cases, they correspond to smaller areas or even parishes. I randomly sample villages within the list of available villages on each of the 49 State archives of Antenati, and collect marriage certificates in the selected villages. To illustrate the approach, I will use Naples as an example. On Antenati, for Naples, there are 18 neighborhoods in the city and 71 villages in the province on the Antenati platform. I randomly sample neighborhoods and villages from the list of neighborhoods and villages. Then, to determine the number of certificates to be collected in each village, I consider the fact that according to sample size calculations (see Appendix A2), the minimum sample size is 1216 certificates. The population figure of the province of Naples in 1815 is 667,389 (see Mariella et al. 2020 and supplemental material). The overall population of the portions of Italy covered in this sample is 16,916,109. Converting the population share of Naples to the corresponding marriage rate using the best available figures of marriages per inhabitant (see Appendix A3), Naples must have at least 0.0372 × 1216 = 45.34 certificates.

One may wonder why, instead of directly sampling marriage certificates, marriage certificates should be drawn at random within villages. The reason is that on the platform, the most disaggregated unit of observation is pictures containing marriage certificates, rather than certificates themselves, and there is no one-to-one relation between pictures and certificates: depending on the selected village, a picture might contain several marriage certificates (e.g., Fig. 1) or only a part of a single marriage certificate that develops over more pages (e.g., Fig. 2). A clustered random sampling scheme solves the resulting risk of oversampling areas with more than one marriage certificate per picture because it samples units (villages) that are more aggregated than marriage certificates.Footnote 21 In the sampling procedure, I use two main weights to post-stratify the obtained sample in an iterative fashion to have enough observations in each gender, region, and urban–rural cell.Footnote 22 The first weight is the one indicating that, for example, at least 45 certificates should be collected in Naples; it is composed of a population weight, which is the total sample size divided by the regional population weight of the area adjusted by their marriage rate, and an archival weight, which indicates the minimum number of certificates to collect in each archive over the total of the region. The weight corrects for between-region variability in archive coverage with regional and provincial population estimates for 1815 drawn from Mariella et al. (2020), whose data reconstruction can be considered the most updated and complete.

Marriage certificate from Campobello, Sicily (1820). Content: The spouses, their spouses and the witnesses of marriage no. 5 (left side) have declared of not being able to write. In marriage no. 6 (right side), the groom is Gaetano Ferraresi, aged 21, a crivellatore (miner), residing in Campobello, son of Carmelo Ferraresi, aged 50, a crivellatore, and Maria Cassaro, aged 37, of unspecified occupation. The bride is Rosa d’Andrea, aged 16, resident in Campobello, of unspecified occupation, son of Calogero d’Andrea Cassaro, deceased, and Maria Vella, aged 46, also of unspecified occupation

When the Antenati archive does not include all provinces within a region, the first weight stratifies by the population of unitary regions, and when the data collection is more complete, the first weight stratifies by the smaller level of pre-unitary province (see Appendix A3 for more details). The second weight is an urban–rural weight and corrects for the share of urban areas in the region; the population was derived from the 1800 estimations of Malanima (2016). I introduce an indicator to distinguish cities from agricultural agglomerations (‘agro-towns’) and only include cities in the urban population (Blok 1969; King and Strachan 1978; Salvo and Zichichi 2003; Curtis 2013). I consider 9000 in 1800 as the minimum population threshold for larger towns in 1815, and 4000 as minimum threshold for smaller towns. I also assume that when town size in 1800 is smaller than 5000, it is 4000. For Naples 62% of certificates should come from urban areas and 15% should come from rural areas, so I collect certificates in urban and rural villages respecting the proportion.Footnote 23 Sensitivity analyses suggest that the results and coverage in Northern Italy would be dramatically underestimated if not using weights, because in Northern Italy, the real population is larger than the number of marriage certificates on the Antenati platform would suggest. The results are instead quite similar when considering the 15–30 marriage cohort and the 30–40 marriage cohort separately instead of the entire one (see Appendix Tables 17 and 18).

A clustered random sampling also has the advantage of allowing for analyses that better represent the specific village than randomly picking certificates from different villages. It also allows to integrate the research with qualitative information by village. Also, the process of random selection can be clearly documented because it is based on the list of potential villages to select that was created before starting to sample. The coverage is uniform across the areas of Italy that are contained in digitized archives (see Fig. 3). After the post-stratification, each region or province, and each urban and rural area has a balanced number of certificates (see Table 11 in Appendix 1). Although three regions are missing, the universe of interest for which this sample is representative at the level of region and province is most of continental Italy (see Figs. 7, 8, and 9 in Appendix 1). Table 1 summarizes literacy rates with averages across important dimensions such as macroarea, gender, urban–rural, and occupation. The results will be critically discussed with a regression approach in the next subsection.

4.2 Regression-based adjustments

I use a regression approach to further correct for sampling imbalances. Regressions rely on more assumptions than the simple averages of Table 1. But a regression has the advantage of allowing for flexible balancing of the sample along dimensions that could not be stratified on when collecting the data, such as occupations. Skills and occupations are arguably crucial to explain literacy even after controlling for gender and urban–rural dimensions. For example, suppose that in 1815, the real population of women working as weavers in urban Northern Italy is 20%. The sampling approach cannot stratify on occupations, and as a result, it might accidentally contain only 5% of brides that work as weavers in urban Northern Italy, despite collecting the correct proportion of certificates given the population and urban–rural share of the selected area.

As the literacy rates of weavers tend to be low, women’s literacy rates in urban Northern Italy would consequently be overestimated. As an additional indirect effect, with other things equal, this sample bias would drive up literacy rates for the entire North, for urban areas, and for grooms. To mitigate this concern and safely add the dimension of literacy rates by occupation, I adapt the approach of Clark (2005), who introduced it to estimate real wages in England, to a context where the variability is within many dimensions, but in a single cross section (area, gender, urban–rural, skill), rather than predominantly over time, and where the dependent variable is binary.Footnote 24 I estimate literacy rates in a (logit) regression framework controlling for skill, gender, urban/rural and regional dummies as follows:

where \({\text{Lit}}_{i}\) is the ability to sign of the i-th observation; \({\text{Skill}}_{i}\) is a categorical variable with three values: primary, secondary and tertiary derived from HISCLASS 12; \({\text{Gender}}_{i}\) is a gender dummy; \({\text{URBRATE}}_{j}\) is a categorical variable indicating whether individual i resides in an urban or in a rural area within area j; and \(L{\text{OC}}_{j}\) is a categorical variable with a value for each province, region or macroarea considered. As it was not possible to stratify the sample by skill levels without sampling all marriage certificates, in order to consider also the skill dimension in the regression, I aggregate the results by macroarea (North, Centre and South) to have enough observations for each skill level. To obtain literacy rates in each cell (e.g., for skilled women employed in the urban part of Northern Italy) I use the odds of the logit regression to predict the average marginal effect of being literate versus illiterate across each dimension (e.g., whether working in agriculture, industry, or services), fixing the categories of the remaining covariates (e.g., for women located in urban Northern Italy). Table 2 shows the resulting literacy rates. The resulting estimates are very disaggregated by macroarea, skill, urban–rural, and gender dimensions. The estimates suggest that Southern and Central Italy were very similar in terms of literacy rates also across occupations and Northern Italy instead had higher literacy rates also in rural areas. In order to have a more aggregate picture and to compare the regression estimates with the simple average estimates, as a next step I aggregate literacy rates within each of the dimensions and across gender, urban–rural, and skill dimensions. This gives us literacy rates of, say, of all women, or of all urban dwellers, or of all individuals in Northern Italy, rather than those of more detailed categories such as women in the North, employed in services in urban sectors. To do so, I aggregate the coefficients of Table 2 by North, Centre, and South using population, urban–rural, and skill weights. The population and urban–rural weights are to the weights used to post-stratify the sample. As some provinces and regions were not covered in the sample, I use weights that only include covered areas. The skill weight is obtained from Chilosi and Ciccarelli (2022).Footnote 25 The regression approach yields estimates reassuringly similar to those resulting from the simple average approach across the macroarea and gender dimensions, granting us the confidence that the results of the sampling procedure are robust to the important omitted variable of skills (compare Table 1 and Appendix Table 11). For this reason, regressions will only be used to add the important skill dimension to the picture (Tables 2 and 3).

The regression estimates differ from the simple average ones across the urban–rural dimension, particularly in central Italy.

The reason is of a technical nature: from Chilosi and Ciccarelli (2022) we can observe the proportion of skilled individuals by gender, but the skill weights are not disaggregated by urban and rural dimensions. Therefore, we cannot safely aggregate the literacy estimates of Table 2 along the urban–rural dimension. To see why, suppose we want to find the literacy rates of urban and rural Northern Italy. According to Chilosi and Ciccarelli (2022, 1360), in 1815 there are 64% individuals employed in the primary sector, 18% in industry, and 18% in services across Northern (and Central) Italy.

The sample has 60% individuals employed in the primary sector, 28% in industry, and 12% in services. If we could assume that the occupational shares were similar between urban and rural areas, we would use the overall weight of Chilosi and Ciccarelli (2022) also to look at urban–rural differences. But in urban areas of Northern Italy, our sample has only 28% individuals employed in the primary sector, 52% in industry, and 20% in services. Although these figures may be skewed due to sampling biases, they are more likely to reflect the rates of cities than the aggregate figures of Chilosi and Ciccarelli (2022), which include the vastly different occupational structure of rural areas. Using Ciccarelli and Chilosi’s weights to compare the literacy rates of urban and rural individuals in the North would overestimate the proportion of peasants also in urban areas, thus underestimating literacy rates in urban areas, and overestimating it in rural areas. This is indeed what I observe (see Appendix Table 14), and for this reason I prefer to present the urban–rural literacy averages obtained directly from the population and urban–rural sample (Table 1).

5 Literacy rates in 1815

5.1 The new estimates

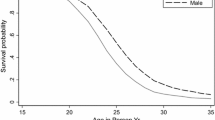

In this section I describe and interpret the new estimates of human capital in early Risorgimento Italy. The key results by macroarea, gender, and urban–rural are drawn from the simple averages of Table 1, and the results by occupation are drawn from the regression outputs of Tables 2 and 3. The North versus Central–South and gender gaps in literacy rates are wide. On average, spouses of Northern Italy signed 13.7% more certificates than Southern spouses (Table 1). Considering the lower bound of Southern literacy rates at 11.4% and the upper bound of Northern literacy rates at 27.4%, the difference becomes approximately 16 percentage points. The estimates of the regression approach are close to the estimates constructed using our stratified sample (compare Table 1 with Table 14 in Appendix). Importantly, the North-Centre gap is comparable in size to the North–South gap. Northern Italian spouses could sign marriage certificates 26.2% of the time, while their Central and Southern Italian counterparts did so 16% and 12.5% of the time on average, respectively.

The gap is mostly explained by the high literacy rates of Piedmont in the North and the low literacy rates of most Southern and Central Italy, except for Tuscany, Basilicata, and Campania (Figs. 4a and 9b). The provinces in Calabria, Apulia, and Basilicata have the lowest literacy rates in the South; the central regions of Tuscany and Marche closely match the literacy levels of southern regions; the literacy rate of the Emilia-Romagna region in the Centre–North, formerly half part of the Papal State is half that of the neighboring region of Lombardy, and similar to that of the province of Principato Citeriore (Salerno) in the South. Literacy gender gaps are consistently high throughout Italy, and lower only in the regions of Italy with lower average literacy rates (Fig. 4). 31.3% of grooms signed the marriage certificates, while only 9.2% of brides did (Table 1). The resulting literacy Gender Parity Index (GPI), the ratio of female to male literacy, is 29.5%, with a clear North–South pattern increasing as one moves North (see also Fig. 4b). The North–South ratio for female literacy rates in 1815 is 2.64. This is almost equivalent to 2.7, that is the value provided by Cappelli and Vasta (2020a) and based on elaborations from Ciccarelli and Weisdorf (2019)’s data for 1821. This ratio reached levels as high as 3.5 in 1860, suggesting that it widened markedly during the early nineteenth-century. Southern and Central Italy are surprisingly similar in terms of aggregate literacy rates, also across gender, urban–rural and occupational dimensions. In the North, the urban–rural literacy gap is very marked, while in the South it is almost nonexistent (see Table 1). This might explain why, over time, literacy rates increased in Northern Italy, while they did not in the South: the new model of school-based education focused first on urban agglomerations before diffusing in rural areas. The fact that urban areas in Northern Italy had higher literacy rates than urban areas in the South suggests that in Northern Italy, the process of schooling diffusion had already started and would have radically changed the scale of literacy diffusion over time. The wider spatial diffusion but lower overall level of literacy rates suggests that, besides large cities such as Naples, this diffusion still had to be initiated there.Footnote 26 The literacy rates of farmers (HISCLASS codes 8, 10, and 12) were at 10.4%, while workers in industry (HISCLASS codes 6, 7, 9, and 11) could sign in marriage certificates 25.2% of the time on average (Table 3). Among spouses of higher status (HISCLASS codes 1 to 5), mostly working in services, 44.7% of them could sign a marriage certificate. The literacy rate of Northern Italian farmers was twice the average literacy rate of Central and Southern Italy. This can be historically explained with the effort to diffuse primary schooling throughout Northern rural areas, and particularly in the Lombardy ruled by Joseph II of Habsburg-Lorena. Literacy rates in the North are especially high among farmers (15.5%) and among services workers (56.7%) compared to the rest of Italy.

I now compare the Antenati results with unitary census-based retropolated estimations of Ciccarelli and Weisdorf (see Fig. 5 and Table 4).Footnote 27 The Antenati figures date back to around 1815 for spouses aged 23 years old on average. Ciccarelli and Weisdorf (2019) instead uses the cohort of individuals aged 90 to 100 years old in the 1881 census to infer the literacy rates of the group aged 30–40 in 1821. As a result, we should not expect the two numbers to be equal, as the Antenati estimates are direct and rely on marriage certificates rather than retropolating census information. The most remarkable difference is that the estimates of Ciccarelli and Weisdorf are much higher for Northern and Central Italy than the 1815 Antenati sample estimates, while they are more similar for Southern Italy. In the North, literacy rates were 26.2% in the Antenati sample and 36.6% in Ciccarelli and Weisdorf (see Table 4 and Appendix Fig. 15). According to Ciccarelli and Weisdorf (2019), the North–South gap in levels in Italy was 20 percentage points, while this study found it to be 13.7 percentage points, thus smaller of 6.3 percentage points than previously estimated. The South represented 45.3% of the literacy of the North in Ciccarelli and Weisdorf (2019) and 47.7% in the Antenati sample (Table 4, panel B). This suggests that the size of the North–South gap was smaller than in Ciccarelli and Weisdorf (2019) because literacy rates were systematically lower in this study, rather than because the South represented a smaller share of the North’s literacy rate.

The difference in North–South literacy levels is especially pronounced for women. In 1815, the difference in female literacy rates between Northern and Southern Italy was as little as 7.5 percentage points and the female literacy rate in the South accounted for only 38% of the Northern literacy rate.Footnote 28 The high literacy gender gap that Ciccarelli and Weisdorf (2019) detected for women within Southern Italy appears now to be a more general feature of Italy at large. Female literacy rates in Antenati are only 9.2%, and they are almost double (16.2%) in the census retropolations of Ciccarelli and Weisdorf (2019) (see also Appendix Fig. 15)Footnote 29 For males, instead, the literacy rates in Antenati appear lower but more in line with Ciccarelli and Weisdorf’s.

Why were literacy rates more similar across Italy than previously estimated, and especially so for women? I put forth a tentative explanation that includes both historical and technical arguments. The Antenati estimates measure ‘pre-Napoleonic’ literacy rates for spouses who could attend primary schools just before the French reforms. At the time, North–South differences in State efforts to provide access to primary schooling were limited. Only parts of Lombardy in the North and urban Naples in the South already received systematic public schooling efforts. Institutional divides in educational provision were not as marked as after the French reforms, and primary schools relied on private institutions charging tuition fees both in the North and in the South.

Women suffered the most in this educational system, because it is plausible to argue that only wealthy families could invest in the education of both their sons and daughters, especially in teaching them to write and not just to read or to learn ‘lavori femminili’ such as knitting and mending.Footnote 30 For women, such historical insights and the fact that the gap did not change much from 1815 to 1861 support the tentative explanation that unlike for men, pre-Napoleonic factors played a dominant role in explaining the high North–South literacy gaps of 1815 of women. The fact that in 1815 the literacy gender gap is especially marked in Piedmont where most primary schools were private (Chilosi 2007, 419) and less marked in Lombardy, where the Austrian government had already expanded public female schooling, supports this explanation (see Fig. 4b). The 1911 Daneo-Credaro school centralization reform raised female literacy rates in 1911 (Cappelli and Vasta 2020a).

Comparing the new 1815 estimates with unitary censuses of 1861 and 1871 (e.g., A’Hearn and Vecchi 2017, 178) suggests two possible perspectives on the history of education from the Napoleonic period to the Unification. The estimates of Ciccarelli and Weisdorf (2019) suggest a stagnation of literacy rates, while the new direct estimates suggest a sizeable increase during the Restauration.Footnote 31 Although a preliminary conjecture, it is plausible to assume that the strong centralization feature of French reforms and the legacy of later Restoration reforms in the North led to a first ‘Silent Revolution’ for women, which lowered the literacy gender gap there considerably over the Risorgimento period and increased women’s literacy rates across Italy. With new public schools becoming open also to women, more of them could attend schools that taught them to write rather than lavori femminili. This increase in female literacy happened in the North and, although to a limited extent, also in the South.Footnote 32 As a result, the North–South gap in female literacy rates slightly diminished over the Risorgimento period (see Table 5).

Schooling reforms during the Napoleonic and Risorgimento periods seem to be associated with a new, regionally unequal pattern of human capital accumulation for men, in contrast to a more uniform rise in female literacy rates. This disparity was primarily driven by a stagnation in literacy rates in the South (see Table 5): in 1815, the male literacy rate in the South was roughly half that of the North (51%), but it fell to a quarter of the North’s (23%) between the end of the Napoleonic period and the political unification of 1861.

Unlike the Daneo-Credaro reform, pre-unitary primary schooling reforms closed gender gaps in a very regionally unequal manner. The North was more exposed to pre-unitary reforms, and as a result, literacy rates increased more there than in the South.Footnote 33 The spatially unequal pattern of post-Napoleonic primary school diffusion had a particularly strong impact on male literacy rates in 1861. Instead, the post-1815 regionally unequal centralization reforms in public schooling provision partially reduced female literacy gaps. The available sources do not allow us to compare the occupational structure of the Antenati sample with local studies for women as they do for men (see Appendix Table 14). But the Antenati sample, even though it is not balanced in its sample composition according to the occupational structure (and this is why I used regression approaches to disaggregate literacy rates by occupation in Sect. 4), still shows important North versus Centre–South differences in the occupational structure. Northern Italy has substantially more women employed in the secondary sector and less in the primary sector than the rest of Italy (see Fig. 6).

The socioeconomic structure of Northern Italy was still different from that of Southern Italy, suggesting that the different results are not driven by sample composition. A less agrarian occupational structure of women in the North did not translate into substantially higher female literacy rates in the North, possibly due to the institutional obstacles that a system based on private education implied at the time for all women except those originating from wealthy families. More technical aspects relate to the fact that cohorts in more recent censuses can explain the discrepancies between the results using the 1871 census and the estimates by Ciccarelli and Weisdorf, who used the 1881 census, but cannot entirely explain the difference that we observe between our sample and either the 1881 or 1871 censuses. Other explanations can relate to issues of census data retropolations: selective mortality, cohort effects, differences between stated (census) and proved literacy abilities (signatures), and age heaping (see the supplemental material for a technical discussion). Taking the uncertainty that all such biases—which cannot be circumvented—imply for an even comparison, figures from marriage certificates and censuses are comparable, but highlight a different picture of the Italian North–South divides: the regional divides are less marked because literacy rates are generally low, and Central Italy has literacy rates more comparable to the South than to Northern Italy.

5.2 Comparison with local studies

As a last exercise, I compare the Antenati sample literacy rates with a set of local estimates, including new ones collected for this study. In this paper, a ‘local study’ is a study that contains quantitative estimates of literacy rates based on signatures in local areas such as villages and that can sum up to provinces or regions (see Table 5). Caution is necessary when comparing the estimates, as they often refer to selected areas of the selected regions or cities.Footnote 34

Local studies provide precious information for three primary purposes. First, local studies can help to explain differences between previous studies. Literacy rates in Lombardy and Marche are broken down by occupational class, according to local studies. This allows us to compare the proportion of people employed in various sectors in Antenati and in local studies, as well as the literacy rates of each class. According to local studies, 46.2% of male spouses in Lombardy can sign, while 37% can sign according to the Antenati sample. The literacy rate by occupational sector is very close in Antenati and in local studies (see Appendix Table 12). Thanks to the disaggregation of literacy rates by occupational sector, we know that the difference can be attributed to the fact that in the local studies, more than 18% of individuals are landowners, compared to 7% in Antenati. The Antenati sample for Lombardy also includes 62% of workers in the primary sector, whereas local studies only include about 52%. The overrepresentation of landowners in Lombardy local studies, driven by an overrepresentation of hilly areas in Lombardy local studies, can explain why literacy rates in Lombardy are higher according to local studies (see supplemental material for further discussion). A similar logic can be applied to Marche, albeit with a smaller sample of villages in local studies.

Local studies can also be used to validate the representativeness of specific parts of the sample when there is reason to believe that the randomly selected villages do not accurately represent the unsampled ones. This bias is inherent in all random sampling methods, but it is frequently difficult to quantify. Local studies allow us to estimate how sensitive specific results are to chance imbalances. Consider Abruzzo Ulteriore II as an example. The province stands out as an outlier with literacy rates comparable to those of Naples (see Fig. 5). As a local study, I collected 50% of the signatures of the entire Abruzzo Ulteriore II whose resulting average literacy rate is 14.9%, lower than the Antenati sample in Abruzzo Ulteriore II by about 10 percentage points (see Table 6). The overestimation for Abruzzo Ulteriore II does not change the overall literacy rate estimates across macroarea.Footnote 35

This is reassuring because it shows that the sample estimations are robust even with the Antenati sample's possibly highest random imbalance.Footnote 36 A similar type of local study was conducted for the provinces of Salerno and Udine, where instead the Antenati sample correctly represents the population literacy rate.

Finally, local studies can provide us with more historically informative insights. For example, the city of Naples stands out because thanks to the additional information which can be obtained from the 1750 and 1775 processetti matrimoniali (see Table 6 and Appendix A4). In 1750, literacy rates were already high for grooms in central Naples (28.76%). Literacy rates reached levels as high as 57% for grooms in 1810 and 1815, just before the Napoleonic reforms but after the effect of the Absolutist rulers' reforms, according to the full set of certificates collected by Alfonso Scirocco (1987) and 52% according to Antenati. This indicates that the city of Naples witnessed an important rise in literacy rates before 1815, which placed it at a comparable level to the literacy rates of Lombardy in the North as measured by the data-rich studies of Xenio Toscani. But it also indicates that, unlike in Lombardy, the effort in the Kingdom of Naples was placed on raising literacy rates in more élite parts of the country, such as Naples itself, while neglecting to diffuse this model of literacy expansion elsewhere.

6 Conclusion

The debate on the origins of the North–South divide is one of the most enduring and intriguing in Italian economic history. This paper contributes to this debate with direct estimates of literacy rates in the early nineteenth century, primarily using signatures drawn from a random sample of marriage certificates. The main finding is that the North–South gap in 1815 was smaller than previously assumed because Northern and Central Italian literacy rates were lower than expected. This suggests that, although pre-Napoleonic educational efforts were also important, and particularly for women, the large North–South human capital divide observed in unified Italy is to be traced back to the Napoleonic or Restoration reforms. The restored Southern Borbonic Kingdom's failure to build new primary schools in the run-up to unification may have exacerbated the differences in schooling. Meanwhile, the fact that women’s literacy rates were as low as 9.2% across Italy in 1815 may suggest that the reorganization of schools after the French period was critical to closing the gender gap in literacy education before the unification, similarly to the Daneo-Credaro school centralization reform of 1911 (Cappelli and Vasta 2020a).

In 1815, literacy rates were particularly high in areas exposed to the public education reform, for example the Austrian-ruled Northern region of Lombardy, the Borbonic Southern region of Campania, and Naples in particular. This suggests a tentative association between the centralized decision-making in education by the government and high literacy rates despite different socioeconomic backgrounds. In explaining the divergence in literacy between the Northern and the Southern regions that occurred after the Unification, some scholars (Vasta 1999; Felice and Vasta 2015, 58; Cappelli and Vasta 2020b, 161) argue that the decentralized nature of the 1859 Casati Law limited the diffusion of literacy.Footnote 37 Within this wider debate, the pre-unitary evidence indirectly suggests that even if partially enforced, school centralization reforms in 1861 would have been beneficial to leveling out literacy divides across unified Italy. The new evidence from 1815, by showing that literacy rates were higher where school centralization reforms where even only partially enacted, indirectly supports the hypothesis that also a centralized Casati Law would have contributed in leveling the divides after the Unification, rather than exacerbating them.

It is still unclear whether school centralization across pre-unitary Italy would have been sufficient to level the divide. Italy was a heterogeneous country, and other facts about how school reforms were implemented besides centralization arguably mattered. For instance, the longer exposure to the Napoleonic reforms in the Northern States led to higher unitary literacy rates there (Postigliola and Rota 2020). The fact that before the French reforms, women’s literacy rates were low not just in the South, but also in the North and in the Centre, suggests that the heterogeneously adopted French reforms contributed to raising female literacy rates only in the North and Centre of Italy. The finding of this paper that Central and Southern Italian literacy rates were almost identical in 1815 supports Bozzano, Cappelli and Vasta (2023), who show that before the Unification, the North adopted a model of educational provision completely at odds with that of the Centre and South. The goal of the Northern Italian schooling system was to increase enrollment rates for all, at the cost of a lower quality of education, while the Centre and the South, despite centralizing de iure schooling provision, gradually invested more resources in an elitist model of high-quality schooling. It is not too far-fetched either to speculate that the burden of financing schooling left to each municipality may have contributed to widening the divide: Northern Italian municipalities dedicated more funds to education than Southern ones, and this can explain the widening North–South divide after the French period.

Disentangling the role of the Napoleonic domination with that of later administration of pre-unitary states in order to understand the respective roles in the literacy rates and divides would be a valuable direction of future research. Another important way forward would be to focus on the interaction of demand factors behind literacy rates with institutional reforms such as the Restoration ones. For instance, future works may expand this sample by placing more emphasis on occupations as a proxy for the demand for skills, and may also link literacy rates with the geography of primary school provision to study how the demand for literacy was practically met in this era. Mapping the relationship between female school provision and literacy outcomes would be particularly valuable in learning more about the first ‘Silent Revolution’ that was provisionally observed for women.

Data availability

The data, methods, and replication codes underlying this article are available for further studies and replication that can be accessed via the following link: https://deposit.icpsr.umich.edu/deposit/claimResource?tenant=openicpsr&claimId=45579.

Change history

31 January 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-023-00281-0

Notes

This view of a stagnant Italian economy after the end of the seventeenth century became prevalent after the publication of the essay by Cipolla on the ‘Decline of Italy’ (Cipolla 1952) and of Braudel’s La Méditerranée (Braudel 1949), and was later supported by Cipolla (1989). Aymard (1978) offers a revisionist approach that is discussed in Zamagni (1993, 6–12) and Malanima (2005).

Local studies include Scirocco (1987), Toscani (1987), Piseri (2002), Toscani (1993), Brambilla (1991), Milanesi (1991), and Ferraresi (1991). I do not compare my study only with studies that either focused on later periods (study only with studies that either focused on later periods i.e., Griseri 1973) for Piedmont in 1831–1856), earlier periods (i.e., Pellizzari (1987) for mid eighteenth-century Kingdom of Naples) or on areas not collected in this sample as Sardinia (Pruneri 2011). Considered official statistics are the estimates of Ciccarelli and Weisdorf (2019) for the period 1821–1881, and the 1861, 1871, and 1881 unitary censuses: MAIC (1866a, 388–411), MAIC (1875, 4–239), MAIC (1883, 217–564). I consider individuals aged 18 or more in the 1861 census, rather than aged more than six years old as Cappelli and Quiroga Valle (2021), to better match the age structure of Antenati spouses. I also consider other proxies of literacy after the unification derived from Ministero dell’Istruzione (1890).

The inherent difficulty in collecting often handwritten data from marriage registers scattered over the country has discouraged the use of marriage certificates to derive direct, countrywide estimates of pre-industrial literacy rates from marriage signatures, a notable exception being Schofield (1973).

Starting from the pioneering work of David Mitch (1986), many studies adopted quantitative approaches assess various effects of the early schooling reforms, emphasizing the role of state-driven schooling centralization and political economy considerations. Recent examples include Cappelli and Vasta (2020b) for Italy; Montalbo (2020) for France; Tapia and Martinez-Galarraga (2018) for Spain; Cvrček and Zajicek (2019) for Austria; Cinnirella and Hornung (2016) for Prussia; Andersson and Berger (2019) for Sweden; Milner (2021) for England; Chen et al. (2015) for China.

See Piseri (2017, 21–60) for an excellent introduction.

Postigliola and Rota (2020) provides a precise timeline of the incorporations in the French Empire.

For a detailed description of every legislative measure enacted in the Kingdom of Naples in the Napoleonic decade (1806–1815), see Lupo, Gargano, and Marra (2014).

Banti (1996, 55–97) and Macry (2002) show how noblemen, landowners, small business owners, and professionals in the North and in the South found ways to keep the family wealth concentrated that resembled the ones prohibited by Napoleonic Code on succession (in particular, the majorat) up to the late nineteenth century. It is possible to imagine that families retained a similar unchanged attitude towards education despite the institutional reforms.

To avoid underestimations caused by the absence of the large urban areas of Genoa and Milan, large urban areas are proxied by reasonably similar cities for which certificates are available, such as Turin and Venice, and missing observations from urban areas are proxied by similar observations from neighboring provinces (see Appendix Sect. A3 for further details).

In the Antenati sample, the North of Italy is composed of the regions of Liguria, Piedmont, Lombardy, Venetia, and Emilia-Romagna. The Centre of Italy is composed of the regions of Tuscany and Marche. The South of Italy is composed of the provinces of Terra di Lavoro, Abruzzo Ulteriore I, Abruzzo Ulteriore II, Abruzzo Citra, Basilicata, Calabria Ultra I, Calabria Ultra II, Catania, Girgenti, Messina, Molise, Napoli, Noto, Palermo, Principato Citeriore, Principato Ulteriore, Terra d’Otranto, Terra di Bari, and Trapani. Appendix Table 13 shows covered and non-covered parts of Italy.

Occupations were coded according to the HISCO and HISCLASS classifications of Van Leeuwen (2002) and Van Leeuwen and Maas (2011). The official sources I use are MAIC (1866a, b); MAIC (1875); MAIC (1883); MAIC (1900), and Ministero dell’Istruzione (1890). I also refer to the elaborations of census data of Ciccarelli and Weisdorf (2019).

If a person can sign a certificate, this does not mean that she can access book production or the popular press (see Marchesini 1992). There are sources that enable measurement of more complex literacy skills, such as receipts of payments but these sources are scattered and hardly systematic (see Petrucci 1987). I classified trembling signatures as ‘poor handwriting.’

In 1851 there were 151,227 religious workers, 130,003 mariners, and 260,209 beggars (mendicanti) out of a population estimated to be 10,729,539 (ASI 1853, 68–71). Religious workers and mariners are likely to be more literate than the average population, whereas beggars are less likely to be literate. Because the two groups are similar in size, we should not expect significant differences in literacy between included and excluded individuals.

‘Ces deux exemples illustrent la negligence de maints cures quin ne rédigent pas les actes au fur et à mesure, ce qui les conduit à une multitude d’oublis […] il est bien evident que les paroissiens ne pouvaient pas signer un register où les actes n’étaient pas rédigés!’ (Astoul 1992, 185).

A’Hearn et al. (2022, 119) document that ‘province-level correlations between census literacy [in 1871] and marriage register signature rates, school enrolment rates 10 years later, and conscript literacy test results are in the range + 0.93 and + 0.96 for both men and women.’ In the first three unitary Italian censuses 1861, 1871, and 1881 the enumerators asked if individuals were able to at least read, to read and write, or were analphabet. Each family head received schede del censimento from enumerators (Mastroluca and Verrascina 2012). The illiterate family head had to find a literate individual among neighbors to fill out the forms.

Figure 13 shows that, when broken down by occupational category, some occupations have exceptionally high literacy rates. This is especially true for unskilled workers in the Centre. Figure 14 shows that this is primarily due to Central Italy's smaller sample size compared to North and Southern Italy. The sample cannot be stratified by occupations because they cannot be observed beforehand when collecting certificates, as explained in greater detail in Sect. 4.1. Thus, in order to account for unavoidable sampling imbalances like this one and safely disaggregate literacy rates by occupation categories, I propose a regression approach (Sect. 4.2).

Schofield (1973) cannot observe beforehand how many marriage certificates are contained in each set of parish records, and therefore how to construct a weighted sample of the population, so inference is valid only at the parish-level. Here I can make a step forward because observing the total number of marriages within an archive allows to obtain a balanced sample of marriage certificates at the archive level. Also Cappelli and Vasta (2020b) use a stratified sample of socioeconomic and institutional features of municipalities to study the impact of the Daneo-Credaro schooling reform of 1911 on municipal-level literacy. Another advantage of the clustered sampling scheme is that it solves the issue of there being new certificates introduced on the platform as time goes by, because it considers villages as sampling units, and if a village is available on the Antenati platform it means that the collection is complete for that village. This means that even though the online source is updated over time, my sampling frame does not change as it is based on the list of 5,874 villages with full marriage certificates available in the platform at a specific point in time (December 2022).

For a complete illustration of the procedure, including technical details, a flowchart, and the example for Naples, see Appendix Fig. 9.

If there are insufficient observations in urban or rural cells to represent the sampling weights in the Antenati archive, the missing observations are proxied by those from the closest available province (see Table 7).

Federico et al. (2019a) adopted the approach of Clark to obtain a representative sample of real wages for Italy. They already refined Clark’s approach to mitigate unbalanced samples at given points in time by adding regional population weights. In this paper I further disaggregate the estimates along the gender, urbanization, and skill dimensions.

Suppose that, for instance, we are interested in observing the literacy rates of women in Northern Italy across urban–rural and skill dimensions. Calling a, b, c the literacy rates of women in urban areas and d, e, and f the literacy rates of women in rural areas across the three occupational sectors derived from table 2 and w the weights across the urban–rural and skill dimensions by gender, I aggregate as follows: wwomen,North = wrur ∗ (wserv,North ∗ a(= 33.9) ∗ + wind,North ∗ b(= 14.8) ∗ + wagr, North ∗ c(= 4.9)) + wurb ∗ (wserv, North ∗ d(= 47.8) + wind, North ∗ e(= 23.7) + wagr, North ∗ f(= 8.5)).

See Basile, Ciccarelli, and Groote (2022) for the role of railways in the diffusion of literacy rates from urban to rural Italy.

Linking the Antenati 1815 estimates with the unitary censuses of 1861 and 1871, the trend appears to be similar to that derived from the 1881 census, but the levels of literacy rates are systematically lower.

Enquiries of the Regno Italico (Lombardy and Venetia) of 1805 suggest that only 1/4 of the very few schools (62) open to women taught them to write, and not just to read and to perform lavori femminili (Piseri 2017, 125–127).

Although not widely enforced (see Sect. 2), in the Kingdom of Naples the Napoleonic Decreto Organico della Pubblica Istruzione of 1806 imposed at least one female teacher to be present in every municipality to teach female pupils how to read and write: ‘In ogni città o terra vi saranno uno o più maestri di leggere, scrivere, abaco, e principij di morale per fanciulli. Vi saranno anche delle maestre, che insegneranno alle fanciulle le sopradette cognizioni, e le prime arti donnesche’ (Lupo, Gargano, and Marra 2014, 205) [‘There shall be one or more teachers of reading, writing, abacus, and principles of ethics in every town or land for all boys. There shall also be female teachers who shall teach to girls the disciplines mentioned above, and introductions to the arts of women.’ My own translation].

Bozzano, Cappelli and Vasta (2023, 37) show that the areas of Italy most affected by the French reforms, so Northern Italy and especially the North-West, aimed at increasing school attendance and thus gross enrollment rates rather than improving the efficacy of schooling in the Risorgimento period. As a result, by the unification and during the Liberal Age, North-Western Italy had the highest gap between gross enrolment rates and literacy rates, and enrolment rates far exceeded literacy rates. The gap between literacy and gross enrolment rate (GER) in both private and public primary educational institutions might have been even higher in the Risorgimento years. Already in 1850, the gross enrolment rate of the Kingdom of Sardinia (Piedmont, Liguria, and Sardinia) was as high as 42%, but literacy rates were lower than that (39.5%, according to Ciccarelli and Weisdorf 2019).

‘Local studies’ include Toscani (1987), Piseri (2002), Toscani (1993), Brambilla (1991), Milanesi (1991), Ferraresi (1991). Other studies estimated literacy rates in areas of Italy in the period, but to the best of my knowledge these are the only ones that cover the areas from 1800 to 1861 and for areas also covered in the Antenati sample. For instance, the local studies for Lombardy oversample the areas in the mountains, where literacy rates are higher and the number of landowners is larger; The local estimates for Piedmont and Marche are not very reliable as they only include a very selected part of the region (4 villages for Piedmont and 30 for Marche, concentrated around the regional capital). The estimates for Naples are very detailed but focus only on the central neighborhoods of the city.

Without the 36 observations of Abruzzo Ulteriore II, the literacy rate of the rest of the South (830 observations) is 12.30%. If Abruzzo Ulteriore II had a literacy rate of 14.9% rather than 25% as in the Antenati sample, the South would have a literacy rate of \(12.3*\frac{796}{830}+14.9*\frac{36}{830}\)=12.4%, just 0.13 percentage points lower than the Antenati sample estimate for the South.

The imbalance discussed here is inevitable in random sampling as there is a 5% risk of selecting villages that do not represent the population average at the provincial level (see Appendix section A2). Local studies allow us to appreciate how large this bias is. One might wonder why the sample should not be adjusted if local studies reveal random imbalances, as in Abruzzo Ulteriore II. The main reason is that rerandomizing would imply explicitly selecting a limited number of certificates in such a way to obtain a predetermined literacy rate that we know to be correct. This would add new measurement and selection biases in other dimensions, such as skill levels. Moreover, for Abruzzo Ultra II, it is not necessary because it does not alter the macroarea estimations for the South.

Zamagni (1993) instead argues that the Casati Law positively affected literacy rates.

When the number of villages was very large, as in the case of Udine, I took a random sample of them, covering at least 25% of the considered villages.

I also treated other large urban areas separately from their province (Palermo and Turin).

The provinces and regions that do not have the archive weight because they only have one reference archive are Abruzzo Citra, Abruzzo Ulteriore I, Abruzzo Ulteriore II, Calabria Ultra I, Calabria Ultra II, Catania, Agrigento, Messina, Molise, Ragusa, Salerno, Terra di Bari, Terra di Lavoro, and Trapani.

The archival weight was also adjusted for the number of marriages per inhabitant in the pre-unitary kingdom from ASI (1853, 83). For instance, for the city of Naples, the percentage of certificates, adjusted by the marriage rate of the Kingdom of Naples (138.85), is \(\frac{\left(140.8*18\right)}{11,426,389}*138.85=\mathrm{3,07\%}\), where 11,426,389 is the product of all average marriage certificates by all villages by the number of individuals per marriage in the corresponding pre-unitary state of the province. The corresponding percentage of certificates in the provincial area of Naples is 5,69%. The resulting refined version of the archive weight for the city of Naples is \(\frac{3.07}{5.06+3.07}=0.3504\).

The population weight is similar when using the population directly rather than weighting the population by the marriage rates, but it is less accurate because we are interested in sampling marriage certificates that represent the population shares. For Naples, the resulting population weight would be 4% rather than 3.72%.

The province of Naples is a special case because the size of the archival unit of the city of Naples is such that the urban-rural weight is partially in contrast with the archival weight. In fact, the archival weight told us to sample only 17.15 certificates from the city of Naples, and the large urban weight told us to sample 26 certificates from the city. We should follow the urban-rural weight so as not to collect too many large urban observations from the province compared to what the urban population of the province represents.

I checked whether Northern and Central Italian archives contained signatures of spouses before Napoleon by contacting or visiting the Diocesan archives of Milan, Como, Brescia, Bologna, Florence, Pisa, and Lucca. Northern and Central Italian parish archives sometimes contain signatures for legal processes regarding divorces. However, there are just few such processes, and they are very selected because at the time it was only possible to ask for divorce due to very severe situations of violence, and the spouses were often wealthy.

References

A’Hearn B, Vecchi G (2017) Education. In: Vecchi G (ed) Measuring the Wellbeing of Italians. Oxford University Press, Oxford

A’Hearn B (1998) Institutions, externalities, and economic growth in southern Italy: evidence from the cotton textile industry, 1861–1914. Econ Hist Rev 51:734–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0289.00112

A’Hearn B, Delfino A, Nuvolari A (2022) Rethinking Age Heaping: a cautionary tale from nineteenth-century Italy. Econ Hist Rev 75:111–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.13087

Andersson J, Berger T (2019) Elites and the expansion of education in nineteenth-century Sweden. Econ Hist Rev 72:897–924. https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.12738

Aymard M (1978) La transizione dal feudalesimo al capitalismo. Einaudi, Milano

Álvarez B, Palencia FR (2018) Human capital and earnings in eighteenth-century castile. Explor Econ Hist 67:105–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2017.10.005