Abstract

Background

Current recommendations advocate the achievement of an optimal glucose control (HbA1c < 69 mmol/mol) prior to elective surgery to reduce risks of peri- and post-operative complications, but the relevance for this glycaemic threshold prior to Bariatric Metabolic Surgery (BMS) following a specialist weight management programme remains unclear.

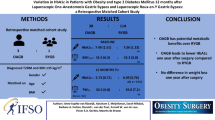

Methods

We undertook a retrospective cohort study of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) who underwent BMS over a 6-year period (2016–2022) at a regional tertiary referral following completion of a specialist multidisciplinary weight management. Post-operative outcomes of interest included 30-day mortality, readmission rates, need for Intensive Care Unit (ICU) care and hospital length of stay (LOS) and were assessed according to HbA1c cut-off values of < 69 (N = 202) and > 69 mmol/mol (N = 67) as well as a continuous variable.

Results

A total of 269 patients with T2D were included in this study. Patients underwent primary Roux en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB, n = 136), Sleeve Gastrectomy (SG, n = 124), insertion of gastric band (n = 4) or one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB, n = 4). No significant differences in the rates of complications were observed between the two groups of pre-operative HbA1c cut-off values. No HbA1c threshold was observed for glycaemic control that would affect the peri- and post-operative complications following BMS.

Conclusions

We observed no associations between pre-operative HbA1C values and the risk of peri- and post-operative complications. In the context of a specialist multidisciplinary weight management programme, optimising pre-operative HbA1C to a recommended target value prior to BMS may not translate into reduced risks of peri- and post-operative complications.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bariatric and metabolic surgery (BMS) is increasingly recognised to be the most effective intervention to induce and maintain significant weight loss amongst patients living with class 2 obesity or above (BMI > 35 kg/m [2]). Amongst patients who have obesity-related comorbidities [1, 2], pre-operative optimisation of medical comorbidities is considered crucial in reducing short- and long-term complications of BMS.

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is present in approximately one-third of patients undergoing BMS [3]. Elevated pre-operative HbA1c level (a measure of chronic hyperglycaemia), typically at > 8% (58 mmol/mol), has been reported to increase the risks of postoperative complications, but this evidence was largely derived from studies involving patients undergoing non-bariatric surgery procedures [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Nevertheless, several consensus statements have advocated postponement of elective surgery, which include BMS, until optimal HbA1c levels were achieved [11, 12]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) along with the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland advocate referral to diabetes specialist teams when HbA1c is ≥ 8.5% (69 mmol/L) [13], whilst the Society for Ambulatory Anaesthesia (SAMBA) recommends a threshold HbA1c level of 7.0% (53 mmol/L) [14].

Achievement of these ‘optimal’ HbA1c values can, however, be challenging for patients undergoing BMS, not least because bariatric surgical options are often sought for patients with poorly controlled HbA1c levels with the aim of improving glycaemic control and inducing diabetes remission [15, 16]. Furthermore, the premise of BMS is not only to induce weight loss but rapid amelioration of obesity-related comorbidities and metabolic complications driven by high HbA1c levels [17, 18]. Several studies undertaken on BMS patients report that elevated HbA1c does not lead to increased postoperative morbidity or mortality in obese patients with diabetes [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. However, many of these studies assess gastric bypass surgery [21, 22, 24] and had limitations such as using HbA1c as a categorical variable, not examining an optimal HbA1c cut-off, not adjusting for important baseline characteristics, not including ICU admissions as an outcome and not including input from a specialist multi-disciplinary team prior to BMS. We therefore sought to report the effects of preoperative HbA1c level on peri-operative outcomes of BMS within the setting of a tertiary referral Bariatric Centre with a view to defining if there is an optimal HbA1c cut-off level and to whether elective BMS should be delayed in patients with elevated HbA1c levels.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who underwent BMS over a 6-year period (2016–2022) at the East Midlands Bariatric Metabolic Institute, Royal Derby Hospital, a regional tertiary referral centre that serves a population of 3.2 million adults. All patients completed a 6- to 12-month tier 3 specialist multidisciplinary weight management programme prior to surgery. Exclusion criteria included the following: patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (as this is not a recognised obesity-related comorbidity) and patients undergoing revisional BMS. All patients underwent a minimum of 2 weeks and a maximum of 4 weeks pre-operative diet supervised by our dietitians.

Collected data included demographic details, anthropometric measurements, laboratory assessments, operation notes, referral and follow-up letters. Post-operative outcomes of interest included 30-day mortality, readmission rates, need for Intensive Care Unit (ICU) care and hospital length of stay (LOS). Surgical complication rates at grades 4 and 5 of the Clavien-Dindo system was collected (although our data was not able to provide adequate information for grades 1 to 3 complications for many patients due to incomplete data recording in nursing and medical notes going back to 2016). There were no missing data for all outcomes we were investigating.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data were analysed using the independent sample t test, whilst categorical data were analysed using Chi-square. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Non-parametric data were analysed using Mann–Whitney and presented as median ± interquartile range (IQR). For dichotomous variables, the chi-squared test was used when values in all cells were greater than five. Otherwise, the p-value for the Fisher’s exact test was used. Simple logistic regression was applied between the HbA1c level with combined risk of complications. Patients were divided into two groups: Group 1 (HbA1c of < 69 mmol/mol) and Group 2 (HbA1c ≥ 69 mmol/mol) to reflect current guidance surrounding the HbA1c thresholds and allow assessment between pre-operative glycaemic control and complications. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 17 software, and significance was accepted at p = 0.05 level.

Results

A total of 269 patients with T2D were included in this study. All patients received tier-3 medical weight management intervention until they were ready to proceed with BMS. Patients underwent primary Roux en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB, n = 136), Sleeve Gastrectomy (SG, n = 124), insertion of gastric band (n = 4) or one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB, n = 4). All procedures were performed laparoscopically. Baseline demographics comparing the two groups are given in Table 1.

In group 1 (n = 202), the majority of BMS patients were women (mean ± SD age, preoperative BMI and HbA1c were 56 ± 10.8 years, 50.7 ± 29.6 kg/m2 and 49.3 ± 9.4 mmol/mol, respectively). In group 2 (n = 67), the majority of BMS patients were male (mean ± SD age, preoperative BMI and HbA1c were 55.2 ± 10.3 years, 48.6 ± 10.4 kg/m2 and 84.7 ± 14.9 mmol/mol, respectively. No significant differences were noted between groups (Table 2).

Peri-operative outcomes including complications, mortality, 30-day readmission, ICU admission and LOS are listed in Table 2. There were no significant differences between the groups. Similarly, no differences were found for the combined risk of complications between groups of HbA1c levels (Table 3). No HbA1c threshold was observed for glycaemic control that would affect the outcomes of BMS.

Discussion

Optimising pre-operative HbA1c levels is an important component of preparation for BMS. However, in selected patients, reductions of HbA1c to < 69 mmol/mol may be challenging. This study in patients living with type 2 diabetes found no statistical difference in LOS stay, ICU admissions, 30-day hospital readmissions or mortality after BMS when comparing preoperative HbA1c values ≥ 69 vs < 69 mmol/mol. Similarly, no threshold for HbA1c level was identified that would influence adverse BS outcomes in patients undergoing BMS. Our data included 27 patients whose HbA1c is > 86 mmol/mol (10%), 12 of whom have HbA1c levels of > 100 mmol/mol (11.3%). Our findings suggest that in the context of a multi-disciplinary physician-supported bariatric surgery service (which also included psychology and dietetic input), BMS can be performed safely in patients with elevated HbA1c levels. Whilst this study is supportive of others undertaken in BMS patients [19,20,21,22,23,24,25], our study addresses previous limitations by including patients who underwent a minimum of 6-months pre-operative MDT input, adjusting for additional confounders and including ICU admission as an outcome measure.

Previous studies in non-BMS patients [4,5,6,7,8,9,10] have provided guidelines and recommendations to achieve ‘optimal’ HbA1c cut-off of < 69 mmol/mol prior to elective surgery, but these findings have not been supported in studies undertaken on BMS patients. Several reasons may explain the discordance between studies in BMS and non-BMS patients. Unlike non-BMS operations, BMS is known to induce significant reductions in glucose levels prior to and after surgery [1, 2]. Improvements in glucose levels are largely driven by the pre-operative liver shrinkage diet which are routinely required for all patients prior to BMS, occasionally in the form of a very low-calorie diet programme as well as other post-BMS metabolic benefits which have been reported to occur independent of weight loss [26]. Furthermore, previous experimental data, albeit in animal studies, have shown that calorie restriction can modulate the physiologic stress response to surgical injury, which likely underlies peri-operative complications, enhance recovery of renal function [27] and mitigate hepatic damage [28] after surgical ischemia–reperfusion injury.

Limitations of this study include retrospective data collection and residual confounding by not including data on Apnoea Hypopnea Index, ethnicity, medications, 24-h blood pressure measurements and relatively small number of patients. In addition, specific surgical complications such as wound infection, need for blood transfusion and the use of anti-emetics are not fully available for all patients going back to 2106 such that data collection for grades 1 to 3 complications via the Clavien-Dindo system is not possible. Similarly, data for pre-operative and post-operative glucose, the use of sliding scale insulin and anti-diabetic therapy included multiple missing data for many patients since 2016 and therefore not included in our analysis. In addition, HbA1c level was monitored locally by individual primary care practices at 6 to 12 months post-operation and therefore not available within our database.

In conclusion, our data suggest that pre-operative HbA1c has limited utility in the decision whether to proceed with BMS and no effect on operative outcomes. Provided patients who are suitable for bariatric surgery undergo a patient-specific integrated multi-disciplinary approach prior to BMS with the aim of co-morbidity optimisation; the arbitrary HbA1c threshold of < 69 mmol/mol should not be used as a basis to exclude or delay patients from having bariatric surgery. Strategies to further optimise HbA1c level prior to surgery include the use of extended liver shrinkage diets pre-operatively, as is commonplace in our Centre. Additionally, detailed preoperative counselling of patients with regard to the risks and benefits of proceeding with BMS, in the context of suboptimal glycaemic control, versus delaying BMS whilst awaiting further glycaemic optimisation is encouraged.

References

NICE. Obesity: clinical assessment and management. 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs127. Accessed 25 Nov 2023

Wolfe BM, Kyach E, Eckel RH. Treatment of Obesity: Weight Loss and Bariatric Surgery Circ Res. 2016;118(11):1844–55.

Fountain D, Alkharaiji M, Awad S et al. Prevalence of co-morbidities in a specialist weight management programme prior to bariatric surgery. Br J of Diabetes. 2019;19:8–13.

Halkos ME, Lattouf OM, Puskas JD, et al. Elevated preoperative hemoglobin A1 c level is associated with reduced long-term survival after coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(5):1431–7.

Gustafsson UO, Thorell A, Soop M et al. Haemoglobin A1 c as a predictor of postoperative hyperglycaemia and complications after major colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2009;96(11):1358–64.

O’Sullivan CJ, Hynes N, Mahendran B, et al. Haemoglobin A1 c (HbA1 C) in non-diabetic and diabetic vascular patients. Is HbA1 C an independent risk factor and predictor of adverse outcome? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;32(2):188–97.

Goodenough CJ, Liang MK, Nguyen MT, et al. Preoperative glycosylated hemoglobin and postoperative glucose together predict major complications after abdominal surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(4):854-8561e1.

Feringa HH, Vidakovic R, Karagiannis SE, Dunkelgrun M, Elhendy A, Boersma E, van Sambeek MR, Noordzij PG, Bax JJ, Poldermans D. Impaired glucose regulation, elevated glycated haemoglocin and cardiac ischaemic events in vascular surgery patients. Diabet Med. 2008;25(3):314–9.

Underwood P, Askari R, Hurwitz S et al. Preoperative A1C and clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes undergoing major noncardiac surgical procedures. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(3):611–6. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-1929.

Mechanick JI, Apovian C, Brethauer S et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutrition, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of patients undergoing bariatric procedures - 2019 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology, the Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery, Obesity Medicine Association, and American Society of Anesthesiologists - executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2019;25(12):1346–59. https://doi.org/10.4158/GL-2019-0406.

Dhatariya K, Flanagan D, Hilton L et al. Management of adults with diabetes undergoing surgery and elective procedures: improving standards. 2011. Available at http://www.diabetologists-abcd.org.uk/jbds/JBDS_IP_Surgery_Adults_Full.pdf. Accessed Jan 2020

Dhatariya K, Levy N, Kilvert A et al. NHS Diabetes guideline for the perioperative management of the adult patient with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491,2012.03582.x.

Membership of the Working Party, Barker P, Creasey PE, Dhatariya K, Levy N, Lipp A, Nathanson MH, Penfold N, Watson B, Woodcock T. Peri-operative management of the surgical patient with diabetes 2015: association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Anaesthesia. 2015;10:1111.

Joshi GP, Chung F, Vann MA et al. Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia consensus statement on perioperative blood glucose management in diabetic patients undergoing ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(6):1378–87. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181f9c288.

DE Cummings. Endocrine mechanisms mediating remission of diabetes after gastric bypass surgery. s.l.: International Journal of Obesity, 2009:33 Suppl 1:S33-40.

Dixon JB, Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Rubino F. Bariatric Surgery: an IDF statement for obese Type 2 Diabetes. Diabet Med. 2011;28(6):628–42.

Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity s.l. New England J Med. 2017;376(3):254–66.

Isaman DJM, Rothberg AE, Herman WH. Reconciliation of type 2 diabetes remission rates in studies of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. s.l. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(12):2247–2253.

Basishvili G, Yang J, Nie L et al. HbA1C is not directly associated with complications of bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2021;17(2):271–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2020.10.009.

Stenberg E, Cao Y, Szabo E et al. Risk prediction model for severe postoperative complication in bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-017-3099-2.

Chuah LL, Miras AD, Papamargaritis D et al. Impact of perioperative management of glycemia in severely obese diabetic patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2014.11.004.

Rawlins L, Rawlins MP, Brown CC et al. Effect of elevated hemoglobin A1c in diabetic patients on complication rates after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2012.06.011.

Zaman JA, Shah N, Leverson GE et al. The effects of optimal perioperative glucose control on morbidly obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-5129-x.

Perna M, Romagnuolo J, Morgan K et al. Preoperative hemoglobin A1 c and postoperative glucose control in outcomes after gastric bypass for obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8(6):685–90.

Basishvili G, Yang J, Nie L et al. HbA1C is not directly associated with complications of bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2021;17(2):271–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2020.10.009.

Pucci A, Batterham RL. Mechanisms underlying the weight loss effects of RYGB and SG: Similar yet different. J of Endcorinological Investig. 2019;42:117–28.

Mitchell JR, Verweij M, Brand K et al. Short-term dietary restriction and fasting precondition against ischemia reperfusion injury in mice. Aging Cell. 2010;9:40–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00532.x.

Mauro CR, Tao M, Yu P et al. Preoperative dietary restriction reduces intimal hyperplasia and protects from ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Vasc Surg. 2014;63:500–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2014.07.004.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Retrospective study. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Informed Consent

This was a retrospective study. Informed consent does not apply.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilmington, R., Abuawwad, M., Holt, G. et al. The Effects of Preoperative Glycaemic Control (HbA1c) on Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery Outcomes: Data from a Tertiary-Referral Bariatric Centre in the UK. OBES SURG 34, 850–854 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-023-06964-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-023-06964-x