Abstract

Background

Despite a known significant association between hyperuricemia and obesity, this correlation in bariatric surgery patients remains unknown.

Objectives

To evaluate the prevalence and predictors of pre- and postoperative hyperuricemia in Chinese bariatric surgery patients.

Methods

A retrospective study was performed in 333 bariatric surgery patients from our hospital. The clinical data was collected before surgery and at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively. Univariable and multivariate analyses were used for investigating the independent predictors of hyperuricemia and serum uric acid (SUA) change.

Results

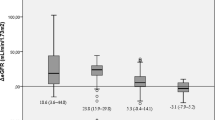

Altogether, 62.9% of patients fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for hyperuricemia. The prevalence of hyperuricemia among males was 81.8% and 62.3% in the women. Multiple logistic regression analyses showed that age (OR = 0.951, 95%CI:0.926–0.976, P = 0.000), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) (OR = 0.217, 95%CI:0.074–0.637, P = 0.005), γ-glutamyltransferase (γ-GT) (OR = 1.016, 95%CI:1.004–1.027, P = 0.006), and creatinine (Cr) (OR = 1.042, 95%CI: 1.017–1.067, P = 0.001) were independent predictors of hyperuricemia. SUA levels significantly declined in all patients from 443.1 ± 118.2 μmol/L before surgery to 370.1 + 113.4 μmol/L at 12 months after surgery. The prevalence of hyperuricemia also declined from 69.4% before surgery to 25.5% at 12 months. Multiple linear regression analyses confirmed that changes in Cr and body mass index (BMI) were independent predictors of a decrease in SUA levels, 12 months postoperatively.

Conclusions

Hyperuricemia in Chinese bariatric surgery candidates are common, especially in males. Age, HDL-c, γ-GT and Cr were determined to be independent predictors of hyperuricemia. Bariatric surgery may effectively reduce the prevalence of hyperuricemia in this population, through postoperative weight loss and changes in creatinine following the procedure.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

21 February 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-022-05971-8

References

Kanbay M, Jensen T, Solak Y, et al. Uric acid in metabolic syndrome: From an innocent bystander to a central player. Eur J Intern Med. 2016; 29(3–8.

Yeo C, Kaushal S, Lim B, et al. Impact of bariatric surgery on serum uric acid levels and the incidence of gout-A meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2019;20(12):1759–70.

Dalbeth N, Gosling AL, Gaffo A, et al. Gout Lancet. 2021;397(10287):1843–55.

Rathmann W, Haastert B, Icks A, et al. Ten-year change in serum uric acid and its relation to changes in other metabolic risk factors in young black and white adults: the CARDIA study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22(7):439–45.

Wang H, Wang L, Xie R, et al. Association of serum uric acid with body mass index: a cross-sectional study from Jiangsu Province. China Iran J Public Health. 2014;43(11):1503–9.

Zhu Y, Zhang Y, Choi HK. The serum urate-lowering impact of weight loss among men with a high cardiovascular risk profile: the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(12):2391–9.

FitzGerald JD, Dalbeth N, Mikuls T, et al. 2020 American college of rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(6):744–60.

Fang J, Alderman MH. Serum uric acid and cardiovascular mortality the NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study, 1971–1992. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Jama. 2000; 283(18): 2404–10.

Liu R, Han C, Wu D, et al. Prevalence of hyperuricemia and gout in mainland china from 2000 to 2014: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2015; 2015(762820.

Osgood K, Krakoff J, Thearle M. Serum uric acid predicts both current and future components of the metabolic syndrome. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2013;11(3):157–62.

Su P, Hong L, Zhao Y, et al. Relationship Between Hyperuricemia and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in a Chinese Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Med Sci Monit. 2015; 21(2707–17.

Gagliardi AC, Miname MH, Santos RD. Uric acid: A marker of increased cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis. 2009;202(1):11–7.

Arterburn D, Wellman R, Emiliano A, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of bariatric procedures for weight loss: A PCORnet Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(11):741–50.

Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):641–51.

Dalbeth N, Chen P, White M, et al. Impact of bariatric surgery on serum urate targets in people with morbid obesity and diabetes: a prospective longitudinal study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(5):797–802.

Maglio C, Peltonen M, Neovius M, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on gout incidence in the Swedish Obese Subjects study: a non-randomised, prospective, controlled intervention trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(4):688–93.

Kasama K, Mui W, Lee WJ, et al. IFSO-APC consensus statements 2011. Obes Surg. 2012;22(5):677–84.

Li L, Zhang Y, Zeng C. Update on the epidemiology, genetics, and therapeutic options of hyperuricemia. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12(7):3167–81.

Chen-Xu M, Yokose C, Rai SK, et al. Contemporary prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the United States and decadal trends: the national health and nutrition examination survey, 2007–2016. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(6):991–9.

Zobbe K, Prieto-Alhambra D, Cordtz R, et al. Secular trends in the incidence and prevalence of gout in Denmark from 1995 to 2015: a nationwide register-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58(5):836–9.

Cho SK, Winkler CA, Lee SJ, et al. The prevalence of hyperuricemia sharply increases from the late menopausal transition stage in middle-aged women. J Clin Med. 2019; 8(3):

Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Mallen C, et al. Rising burden of gout in the UK but continuing suboptimal management: a nationwide population study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(4):661–7.

Liu XY, Wu QY, Chen ZH, et al. Elevated triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (TG/HDL-C) ratio increased risk of hyperuricemia: a 4-year cohort study in China. Endocrine. 2020;68(1):71–80.

Kawachi K, Kataoka H, Manabe S, et al. Low HDL cholesterol as a predictor of chronic kidney disease progression: a cross-classification approach and matched cohort analysis. Heart Vessels. 2019;34(9):1440–55.

Wang F, Zheng J, Ye P, et al. Association of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol with the estimated glomerular filtration rate in a community-based population. PLoS One. 2013; 8(11): e79738.

Bulusu S, Sharma M. What does serum γ-glutamyltransferase tell us as a cardiometabolic risk marker? Ann Clin Biochem. 2016;53(Pt 3):312–32.

Bussler S, Vogel M, Pietzner D, et al. New pediatric percentiles of liver enzyme serum levels (alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, γ-glutamyltransferase): Effects of age, sex, body mass index, and pubertal stage. Hepatology. 2018;68(4):1319–30.

Ali N, Perveen R, Rahman S, et al. Prevalence of hyperuricemia and the relationship between serum uric acid and obesity: A study on Bangladeshi adults. PLoS One. 2018; 13(11): e0206850.

Romero-Talamás H, Daigle CR, Aminian A, et al. The effect of bariatric surgery on gout: a comparative study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(6):1161–5.

Friedman JE, Dallal RM, Lord JL. Gouty attacks occur frequently in postoperative gastric bypass patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(1):11–3.

Xu C, Wen J, Yang H, et al. Factors Influencing Early Serum Uric Acid Fluctuation After Bariatric Surgery in Patients with Hyperuricemia. Obes Surg. 2021;

Liu W, Zhang H, Han X, et al. Uric acid level changes after bariatric surgery in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(14):332.

Ngoh CLY, So JBY, Tiong HY, et al. Effect of weight loss after bariatric surgery on kidney function in a multiethnic Asian population. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(3):600–5.

Carlsson LM, Romeo S, Jacobson P, et al. The incidence of albuminuria after bariatric surgery and usual care in Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS): a prospective controlled intervention trial. Int J Obes (Lond). 2015;39(1):169–75.

Hung KC, Ho CN, Chen IW, et al. Impact of serum uric acid on renal function after bariatric surgery: a retrospective study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16(2):288–95.

Huang H, Lu J, Dai X, et al. Improvement of renal function after bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2021;31(10):4470–84.

Acknowledgements

We thank the funding from Clinical Research Cultivation Program of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (2020LCYB0).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent does not apply.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key Points

• The prevalence of hyperuricemia is very prevalent in Chinese bariatric surgery candidates, especially in males.

• Bariatric surgery may effectively reduce uric acid levels and the prevalence of hyperuricemia.

• The effect of bariatric surgery on uric acid levels is associated with postoperative weight loss and changes in creatinine.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Qu, X., Zheng, L., Zu, B. et al. Prevalence and Clinical Predictors of Hyperuricemia in Chinese Bariatric Surgery Patients. OBES SURG 32, 1508–1515 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-021-05852-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-021-05852-6