Abstract

Background

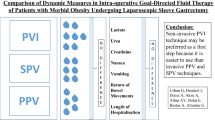

In bariatric surgery, non- or mini-invasive modalities for cardiovascular monitoring are addressed to meet individual variability in hydration needs. The aim of the study was to compare conventional monitoring to an individualized goal-directed therapy (IGDT) regarding the need of perioperative fluids and cardiovascular stability.

Methods

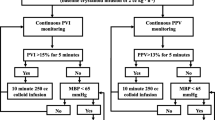

Fifty morbidly obese patients were consecutively scheduled for laparoscopic bariatric surgery (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01873183). The intervention group (IG, n = 30) was investigated preoperatively with transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and rehydrated with colloid fluids if a low level of venous return was detected. During surgery, IGDT was continued with a pulse-contour device (FloTrac™). In the control group (CG, n = 20), conventional monitoring was conducted. The type and amount of perioperative fluids infused, vasoactive/inotropic drugs administered, and blood pressure levels were registered.

Results

In the IG, 213 ± 204 mL colloid fluids were administered as preoperative rehydration vs. no preoperative fluids in the CG (p < 0.001). During surgery, there was no difference in the fluids administered between the groups. Mean arterial blood pressures were higher in the IG vs. the CG both after induction of anesthesia and during surgery (p = 0.001 and p = 0.001).

Conclusions

In morbidly obese patients suspected of being hypovolemic, increased cardiovascular stability may be reached by preoperative rehydration. The management of rehydration should be individualized. Additional invasive monitoring does not appear to have any effect on outcomes in obesity surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Cardiac index

- CO:

-

Cardiac output

- IAP:

-

Intra-abdominal pressure

- IGDT:

-

Individualized goal-directed therapy

- IBW:

-

Ideal body weight

- LV:

-

Left ventricle of the heart

- LOS:

-

Length of hospital stay

- MO:

-

Morbidly obese patients

- Nt-proBNP:

-

N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide

- OR:

-

Operating room

- PEEP:

-

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- PONV:

-

Postoperative nausea and vomiting

- POP:

-

Postoperative recovery unit

- RV:

-

Right ventricle of the heart

- RAP:

-

Right atrial pressure

- RWL:

-

Rapid weight loss

- SV:

-

Stroke volume

- SVV:

-

Stroke volume variation

- TTE:

-

Transthoracic echocardiography

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

References

Nguyen NT, Wolfe BM. The physiologic effects of pneumoperitoneum in the morbidly obese. Ann Surg. 2005;241(2):219–26.

Jain AK, Dutta A. Stroke volume variation as a guide to fluid administration in morbidly obese patients undergoing laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2010;20(6):709–15.

Perel A, Habicher M, Sander M. Bench-to-bedside review: functional hemodynamics during surgery—should it be used for all high-risk cases? Crit Care. 2013;17(1):203.

O’Neill T, Allam J. Anaesthetic considerations and management of the obese patient presenting for bariatric surgery. Curr Anaesth Crit Care. 2010;21(1):16–23.

Cannesson M. Arterial pressure variation and goal-directed fluid therapy. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2010;24(3):487–97.

Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Holte K, Secher NH, et al. Monitoring of peri-operative fluid administration by individualized goal-directed therapy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51(3):331–40.

Poso T, Kesek D, Aroch R, et al. Morbid obesity and optimization of preoperative fluid therapy. Obes Surg. 2013;23(11):1799–805.

Alpert MA, Lambert CR, Panayiotou H, et al. Relation of duration of morbid obesity to left ventricular mass, systolic function, and diastolic filling, and effect of weight loss. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(16):1194–7.

Alpert MA, Chan EJ. Left ventricular morphology and diastolic function in severe obesity: current views. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2012;65(1):1–3.

Poso T, Kesek D, Aroch R, et al. Rapid weight loss is associated with preoperative hypovolemia in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 2013;23(3):306–13.

Lambert DM, Marceau S, Forse RA. Intra-abdominal pressure in the morbidly obese. Obes Surg. 2005;15(9):1225–32.

Vivier E, Metton O, Piriou V, et al. Effects of increased intra-abdominal pressure on central circulation. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96(6):701–7.

Ogunnaike BO, Jones SB, Jones DB, et al. Anesthetic considerations for bariatric surgery. Anesth Analg. 2002;95(6):1793–805.

The expert group rapport of the national guidelines for bariatric surgery (NIOK), Sweden [Internet]. 2009. Available from: www.sfoak.se/wp-content/niok_2009.pdf.

Adams JP, Murphy PG. Obesity in anaesthesia and intensive care. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85(1):91–108.

Bergland A, Gislason H, Raeder J. Fast-track surgery for bariatric laparoscopic gastric bypass with focus on anaesthesia and peri-operative care. Experience with 500 cases. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52(10):1394–9.

Pfister R, Schneider CA. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: application of natriuretic peptides. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(3):382–3.

Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al. Impact of obesity on plasma natriuretic peptide levels. Circulation. 2004;109(5):594–600.

Collins JS, Lemmens HJ, Brodsky JB, et al. Laryngoscopy and morbid obesity: a comparison of the “sniff” and “ramped” positions. Obes Surg. 2004;14(9):1171–5.

Poso T, Kesek D, Winso O, et al. Volatile rapid sequence induction in morbidly obese patients. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28(11):781–7.

Salihoglu Z, Demiroluk S. Demirkiran, Kose Y. Comparison of effects of remifentanil, alfentanil and fentanyl on cardiovascular responses to tracheal intubation in morbidly obese patients. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2002;19(2):125–8.

Casati A, Putzu M. Anesthesia in the obese patient: pharmacokinetic considerations. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17(2):134–45.

Pinsky MR. Heart lung interactions during mechanical ventilation. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2012;18(3):256–60.

Brennan JM, Blair JE, Goonewardena S, et al. Reappraisal of the use of inferior vena cava for estimating right atrial pressure. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2007;20(7):857–61.

Manecke GR. Edwards FloTrac sensor and Vigileo monitor: easy, accurate, reliable cardiac output assessment using the arterial pulse wave. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2005;2(5):523–7.

Mayer J, Boldt J, Poland R, et al. Continuous arterial pressure waveform-based cardiac output using the FloTrac/Vigileo: a review and meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2009;23(3):401–6.

Hofer CK, Senn A, Weibel L, et al. Assessment of stroke volume variation for prediction of fluid responsiveness using the modified FloTrac and PiCCOplus system. Crit Care. 2008;12(3):R82.

De Backer D, Marx G, Tan A, et al. Arterial pressure-based cardiac output monitoring: a multicenter validation of the third-generation software in septic patients. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(2):233–40.

Hoiseth LO, Hoff IE, Myre K, et al. Dynamic variables of fluid responsiveness during pneumoperitoneum and laparoscopic surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012;56(6):777–86.

Raghunathan K, Bloomstone JA, McGee WT. Cardiac output measured with both esophageal Doppler device and Vigileo-FloTrac device. Anesth Analg. 2012;114(5):1141–2.

Meng L, Tran NP, Alexander BS, et al. The impact of phenylephrine, ephedrine, and increased preload on third-generation Vigileo-FloTrac and esophageal doppler cardiac output measurements. Anesth Analg. 2011;113(4):751–7.

Katkhouda N, Mason RJ, Wu B, et al. Evaluation and treatment of patients with cardiac disease undergoing bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8(5):634–40.

Pinsky MR. Hemodynamic monitoring over the past 10 years. Crit Care. 2006;10(1):117.

Alhashemi JA, Cecconi M, Hofer CK. Cardiac output monitoring: an integrative perspective. Crit Care. 2011;15(2):214.

McLean AS, Huang SJ, Kot M, et al. Comparison of cardiac output measurements in critically ill patients: FloTrac/Vigileo vs transthoracic Doppler echocardiography. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011;39(4):590–8.

Canty DJ, Royse CF, Kilpatrick D, et al. The impact of focused transthoracic echocardiography in the pre-operative clinic. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(6):618–25.

Boyd JH, Walley KR. The role of echocardiography in hemodynamic monitoring. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009;15(3):239–43.

Ramsingh D, Alexander B, Cannesson M. Clinical review: does it matter which hemodynamic monitoring system is used? Crit Care. C7 - 208. 2013;17(2):1–13.

Fried M, Yumuk V, Oppert JM, et al. Interdisciplinary European guidelines on metabolic and bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2014;24(1):42–55.

Chamos C, Vele L, Hamilton M, et al. Less invasive methods of advanced hemodynamic monitoring: principles, devices, and their role in the perioperative hemodynamic optimization. Perioper Med (Lond). 2013;2(1):19.

Janmahasatian S, Duffull SB, Ash S, et al. Quantification of lean bodyweight. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44(10):1051–65.

Ingrande J, Brodsky JB, Lemmens HJ. Lean body weight scalar for the anesthetic induction dose of propofol in morbidly obese subjects. Anesth Analg. 2011;113(1):57–62.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Norrbotten County Council.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pösö, T., Winsö, O., Aroch, R. et al. Perioperative Fluid Guidance with Transthoracic Echocardiography and Pulse-Contour Device in Morbidly Obese Patients. OBES SURG 24, 2117–2125 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-014-1329-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-014-1329-4