Abstract

Carbonate precipitation and hydrothermal reaction are the two major processes that remove Mg from seawater. Mg isotopes are significantly (up to 5‰) fractionated during carbonate precipitation by preferential incorporation of 24Mg, while hydrothermal reactions are associated with negligible Mg isotope fractionation by preferential sequestration of 26Mg. Thus, the marine Mg cycle could be reflected by seawater Mg isotopic composition (δ26Mgsw), which might be recorded in marine carbonate. However, carbonates are both texturally and compositionally heterogeneous, and it is unclear which carbonate component is the most reliable for reconstructing δ26Mgsw. In this study, we measured Mg isotopic compositions of limestone samples collected from the early Carboniferous Huangjin Formation in South China. Based on petrographic studies, four carbonate components were recognized: micrite, marine cement, brachiopod shell, and mixture. The four components had distinct δ26Mg: (1) micrite samples ranged from −2.86‰ to −2.97‰; (2) pure marine cements varied from −3.40‰ to −3.54‰, while impure cement samples containing small amount of Rugosa coral skeletons showed a wider range (−3.27‰ to −3.75‰); (3) values for the mixture component were −3.17‰ and −3.49‰; and (4) brachiopod shells ranged from −2.20‰ to −3.07‰, with the thickened hinge area enriched in 24Mg. Due to having multiple carbonate sources, neither the micrite nor the mixture component could be used to reconstruct δ26Mgsw. In addition, the marine cement was homogenous in Mg isotopes, but lacking the fractionation by inorganic carbonate precipitation that is prerequisite for the accurate determination of δ26Mgsw. Furthermore, brachiopod shells had heterogeneous C and Mg isotopes, suggesting a significant vital effect during growth. Overall, the heterogeneous δ26Mg of the Huangjin limestone makes it difficult to reconstruct δ26Mgsw using bulk carbonate/calcareous sediments. Finally, δ26Mgsw was only slightly affected by the faunal composition of carbonate-secreting organisms, even though biogenic carbonate accounts for more than 90% of marine carbonate production in Phanerozoic oceans and there is a wide range (0.2‰–4.8‰) of fractionation during biogenic carbonate formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Secular variation of carbonate mineralogy in the Phanerozoic ocean is observed in both non-skeletal and skeletal carbonate (Stanley and Hardie 1998, 1999; Stanley et al. 2010). Oscillation in the mineralogy of marine carbonate is attributed to fluctuation of the seawater Mg/Ca ratio. When seawater Mg/Ca is high (>2 molar ratio), aragonite and high-magnesium calcite (HMC, with >4 mol% MgCO3) are the preferred carbonate precipitates (aragonite seas); in contrast, low-magnesium calcite (LMC, with <4 mol% MgCO3) precipitation is favored at low seawater Mg/Ca (calcite seas) (Hardie 1996; Stanley and Hardie 1998, 1999). It has been proposed that seawater Mg/Ca is ultimately controlled by the spreading rate of mid-ocean ridges (MOR), which determines the intensity of hydrothermal reactions (Stanley and Hardie 1999). In the high-temperature hydrothermal systems along MOR, oceanic basalt is converted to greenstone by sequestration of seawater Mg2+ into basalts and release of Ca2+ into seawater (Elderfield and Schultz 1996); low-temperature alteration of basalt in ridge flanks also removes seawater Mg (Higgins and Schrag 2015). Thus, a high spreading rate of MOR corresponds with low seawater Mg/Ca, and vice versa (Stanley and Hardie 1999). In an alternative argument, carbonate—particularly dolomite precipitation—consumes most seawater Mg, and thus extensive dolomitization might be the primary reason for low seawater Mg/Ca (Wilkinson and Algeo 1989). Recent research suggests that low-temperature and high-temperature hydrothermal reactions account for comparable amounts of the Mg sink in the modern ocean, while carbonate precipitation leads to about 20%–25% of the total (Higgins and Schrag 2015).

Mg isotopes can be used to quantify the relative contributions of hydrothermal reaction and carbonate precipitation in the marine Mg cycle. It is reasonable to speculate that there is no fractionation in Mg isotopes in high-temperature hydrothermal reactions, because Mg is quantitatively removed from hydrothermal fluids (Elderfield and Schultz 1996). Low-temperature hydrothermal reactions preferentially remove 26Mg from seawater with limited fractionation (<0.7‰) (Higgins and Schrag 2015). In contrast, carbonate precipitation significantly fractionates Mg (up to 5‰) by preferential utilization of 24Mg (Galy et al. 2002; Higgins and Schrag 2010; Immenhauser et al. 2010; Wombacher et al. 2011; Li et al. 2012; Saulnier et al. 2012). For the above reasons, an increase in the size of the carbonate sink would result in higher seawater Mg isotopic composition (δ26Mgsw), while enhanced hydrothermal activities would shift δ26Mgsw in the opposite direction (Tipper et al. 2006b). Thus, δ26Mgsw is a useful proxy in tracing the Mg cycle in paleo oceans.

In order to reconstruct historical δ26Mgsw, suitable material must be selected. Marine carbonate precipitates either biologically or inorganically, with Mg derived from seawater. As such, marine carbonate might record δ26Mgsw. However, most marine carbonates are texturally and compositionally heterogeneous, consisting of different types of carbonate grains (e.g. biogenic clasts, ooids, pelloid), micrite (i.e. lime mud), and cement (Tucker and Wright 1990). It is unclear which carbonate component (if any) faithfully records δ26Mgsw. Furthermore, unlike unconsolidated Cenozoic/modern calcareous sediments (Fantle and Higgins 2014), carbonate rocks have undergone various degrees of diagenesis. It is uncertain whether the pristine seawater signals can be preserved during the lithification processes.

In this study, we measured Mg isotopic compositions of different carbonate components recognized in limestone samples collected from the early Carboniferous Huangjin Formation in South China. Our data indicate that the Huangjin limestones are heterogeneous in Mg isotopes; we discuss the four components’ suitability for reconstructing δ26Mgsw.

2 Geologic background and sample descriptions

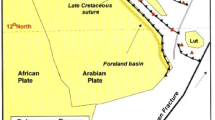

Limestone samples were collected from the early Carboniferous Huangjin Formation in the Mopanshan section, which is located ~15 km southeast of Guilin city, Guangxi Province. The Mopanshan section was located in a carbonate platform during the Carboniferous (Fig. 1). The Devonian–Carboniferous succession in this region consists of, in ascending order, the Upper Devonian Etoucun Formation, and the lower Carboniferous Raoyunling, Yintang, Huangjin, and Luocheng Formations. The 300-m-thick Huangjin Formation unconformably overlies the dolomitic limestone of the Yintang Formation. The lowest 40 m of the Huangjin Formation was measured in this study (Fig. 2). The lower Huangjin Formation is composed of thin- to medium-bedded limestone intercalated with black, organic-rich calcareous mudstone/nodular limestone (Fig. 2). The limestone layers are variably composed of lime mudstone, wackstone, and packstone. The thickness of calcareous mudstone/nodular limestone layers decreases upwardly, while the thin-bedded limestone layers gradually grade to medium-bedded layers (Fig. 2). Both the limestone and mudstone layers are fossiliferous. Brachiopods and Rugosa corals are the two major fossil groups in the lower Huangjin Formation and are normally discovered as complete specimens in both limestone and mudstone layers (Chen and Sun 2013), while other fossils, such as Tabulata corals, foraminifera, crinoids, and bivalves, are less common and normally found as fragments in the limestone layers. Biostratigraphic studies indicate that the lower Huangjin Formation in this region is early Visean in age, equivalent to the foraminifera MFZ12 zone (Hance et al. 2011).

Four specimens from the limestone layers were analyzed in this study. MHR-3 and MHR-8 contained brachiopod fossils, identified as Delepinea subcarinata, which has a pseudopunctate shell structure (Fig. 3a). The brachiopod fossils were hosted in wackstone matrix composed of ~60% lime mud (micrite), 15% foraminifera fragments, 15% brachiopod fragments, 5% other bioclasts (e.g., echinoderm, ostracods), and 5% terrigenous clasts (Fig. 3b). MHR-7 and MHR-5 contained Rugosa coral fossils (Hunanoclisia sp.) preserved in micritic matrix with <5% uncharacterized bioclasts (Fig. 3c). The porous Rugosa skeletons were filled with calcite cement. Cementation started with the precipitation of dogtooth calcispars with coral septa as substrate, followed by the precipitation of bladed calcite crystals. The rest of the interstitial space within the coral skeletons was filled with blocky calcite, representing the final stage of void-filling precipitation (Fig. 3d). This is the typical texture for marine HMC cements that are directly precipitated from seawater (James and Choquette 1983).

Photomicrographs of limestone samples from the early Carboniferous Huangjin Formation, South China. a Delepinea (brachiopod) has a pseudopunctate shell structure (MHR-3); the pseudopunctate structures are indicated by white arrows. b The mixture component of the host rock of Delepinea (MHR-3), consisting of biogenic carbonate grains and lime mud. c The micrite component of the host rock of Rugosa (MHR-5). d Marine cement filling in the skeletal pore spaces of Rugosa coral (Hunanoclisia sp.) (MHR-5). Scale bars are 0.5 mm in all figures

Four carbonate components were identified from the studied Huangjin limestone specimens. A brachiopod shell component was composed of biogenic LMC of brachiopod shell material in MHR-3 (Fig. 3a) and MHR-8. A marine cement component was represented by HMC filling in Rugosa skeletal pores. Although the cement component contained Rugosa skeletal materials, thin section observation indicated that they contributed less than 5% of powder samples (Fig. 3d). The micrite component was collected from the Rugosa host rocks (MHR-5 and MHR-7), and mainly consisted of lime mud (Fig. 3c). The last component identified in this study derived from the host rock of brachiopod fossils (MHR-3), which was a mixture of bioclasts and lime mud (the mixture component, Fig. 3b).

3 Methods

3.1 Sample preparation

Fresh limestone specimens were split using a rock saw, and mirrored thin and thick sections were prepared from each split. Under the guidance of petrographic observation of thin sections, sample powders were micro-drilled from the polished thick sections. About 5–20 mg of carbonate powder was collected from each sample. MHR-3 and MHR-8 were cut through the symmetric plane of brachiopod fossils. Seven samples were collected from the brachiopod shells, including two samples from the thickened hinge area in the pedicle valve, and five from unspecified areas in the pedicle and brachial valves. Two samples of the mixture component were gathered from the host rock of MHR-3. MHR-7 was prepared to expose the transverse section of a Rugosa coral, while MHR-5 was cut longitudinally through a Rugosa fossil. Four samples of the micrite component were collected from the matrix of MHR-5 and MHR-7. In addition, four samples of pure cement and six mixed samples containing both cement and coral skeletal material were collected from the Rugosa fossils in MHR-5 and MHR-7. Powder samples were dissolved in 4 mL 0.5-N acetic acid. After complete dissolution of carbonate, solutions were centrifuged, and the supernatant was split into two aliquots for Mg isotope and elemental composition analyses.

3.2 Column chemistry

Magnesium was purified by cation exchange chromatography at Peking University. The detailed Mg purification procedures have been reported in previous studies (Shen et al. 2009, 2013; Huang et al. 2015). As such, only a brief description is given in the following. First, a sample solution containing ~25–30 μg of Mg was eluted through column #1 (loaded with 1.8 mL Bio-Rad 200–400 mesh AG50W-X12 resin) to separate Mg from Ca. The Mg fraction was collected in 4 mL 10-N HCl, and the Ca retained in the resin. The collected Mg-bearing solution was dried down, and was then loaded onto column #2 (loaded with 0.5 mL Bio-Rad AG50W-X12 resin) to separate Mg from all other elements. This second column step involved the sequential use of 0.8 mL 1-N HCl, 3 mL 1-N HNO3 + 0.5-N HF, and 1 mL 1-N HNO3 to elute Cr, Al, Fe, Na, K, and V. The Mg fraction was then collected with 5 mL 2-N HNO3. Mg concentrations are low in limestone. To ensure a clean Mg fraction, each sample was passed through column #1 three times, followed by two passes of column #2. After the chromatography, Na/Mg, Al/Mg, K/Mg, Ca/Mg, and Fe/Mg were <0.05, and the recovery rates were >99% for all samples.

3.3 Mass spectrometry

Mg isotopic compositions were measured in two laboratories: MHR-3, MHR-5, and MHR-7 were measured with a Thermo Scientific Neptune Plus high-resolution multicollector inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS) at the Isotope Laboratory in China University of Geosciences, Beijing, while MHR-8 was measured with a Nu Plasma MC-ICP-MS at the University of Washington, Seattle. Mg isotope ratios were measured by the standard-sample-standard bracketing method, and analyses were performed in low mass resolution mode, simultaneously measuring 26Mg, 25Mg, and 24Mg. A 400-ppb solution typically gives a 24Mg signal of ~6 V; while the total procedure blank is typically <10−4 V for 24Mg (i.e. containing <10 ng Mg), negligible relative to the sample signals. Analytical results are reported in the delta notation as per mil (‰) deviation relative to the DSM-3 standard (Galy et al. 2003):

Internal precision was determined by three repeated measurements of the same sample solution during a single analytical session, and was better than ±0.1‰ (2SD). Multiple analyses of synthetic solution (GSB-Mg) yielded δ26Mg values ranging from −2.07‰ to −2.04‰ (Table 1), which is within error of the accepted value (−2.05‰ ± 0.05‰ (2σ) (Huang et al. 2015; Peng et al. 2016). δ26Mg of BHVO-2 standard was −0.34‰ ± 0.07‰ (2σ), consistent with previously published data (Pogge von Strandmann et al. 2011; Opfergelt et al. 2012; Teng et al. 2015).

3.4 Element composition measurement

Major and minor element compositions were measured by a Leeman Prodigy inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectrometer (ICP–OES) at China University of Geosciences and by a Spectro Blue Sop ICP–OES at Peking University. Sample solutions were dried down on a hotplate, followed by redissolution in 1-N HNO3. Then, solutions were diluted to within the concentration range of the standard solutions used to construct the calibration curves. The long-term analytical precision as determined by multiple measurements of a synthesized standard solution within a single day (>6 h) was better than 5%. The accuracy was verified by the measurement of USGS basalt standard (BHVO-2).

3.5 C and O isotope measurement

δ13C and δ18O were measured by MAT 253 isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) at Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. About 80–100 μg of carbonate powder was loaded into a glass vial. Carbonate was converted to CO2 by reacting with orthophosphoric acid for 150–200 s at 72 °C in a Kiel IV carbonate device. Isotopic ratios are reported in δ-notation as per mil (‰) deviation relative to the VPDB standard. The analytical precision was better than 0.05‰ for δ13C and 0.1‰ for δ18O.

4 Results

δ26Mg and Mg/Ca ratios are tabulated in Table 1. A Mg three-isotope plot and Mg/Ca–δ26Mg cross-plots are presented in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. δ26Mg of the brachiopod shell component in MHR-3 ranged from −2.20‰ to −2.87‰ (average = −2.47‰, SD = 0.35‰, n = 3). The thickened hinge area in the pedicle valve (−2.87‰) was enriched in 24Mg as compared with the unspecified areas in both pedicle and brachial valves (−2.20‰ and −2.36‰). Two samples of the mixture component were isotopically lighter than the brachiopod shell component (−3.49‰ and −3.17‰). δ26Mg of the brachiopod shell in MHR-8 ranged from −2.23‰ to −3.07‰ (average = −2.62‰, SD = 0.37‰, n = 4) with the hinge area isotopically lighter than the unspecified areas in both pedicle and brachial valves. The micrite components in MHR-7 and MHR-5 had similar isotopic compositions, varying between −2.86‰ and −2.95‰ (average = −2.93‰, SD = 0.05‰, n = 4). δ26Mg of the pure marine cement varied between −3.40‰ and −3.51‰ (average = −3.47‰, SD = 0.07‰, n = 4), while δ26Mg of the mixed samples (cement + Rugosa skeletal material) had wider variation (from −3.27‰ to −3.75‰, average = −3.58‰, SD = 0.16‰, n = 6). Mg/Ca (molar ratio) showed limited variation—between 0.009 and 0.020 with a mean value of 0.015 (SD = 0.003, n = 23).

δ13C and δ18O data are listed in Table 2. δ18O ranged from −4.84‰ to −9.49‰ with an average value of −6.81‰ (n = 23), while δ13C varied between +0.92‰ and +4.14‰ (mean = +3.04‰, n = 23). Brachiopod shells had a narrow range of δ18O (−4.84‰ to −6.08‰) but more dispersed δ13C values (+1.26‰ to +3.34‰). Samples of the cement component had nearly identical δ13C (+3.04‰ to +3.65‰) but more variable δ18O (−9.49‰ to −5.74‰). The four micrite samples had similar δ13C (+3.93‰ to +4.14‰) and δ18O (−8.20‰ to −8.45‰). However, the mixture component had distinct δ13C (+0.92‰ and +3.33‰) but similar δ18O (−5.50‰ and −6.55‰).

5 Discussion

5.1 Verification of sample dissolution procedure

To obtain Mg isotopic compositions of carbonate samples, complete dissolution of carbonate phases is required and contamination from clay minerals should be avoided. So far, there is no standard protocol for carbonate dissolution. In our study, we used 0.5-N acetic acid. Although this procedure had been previously applied for element and Sr isotope analyses (Xiao et al. 2004), further verification is still needed.

To test whether 0.5-N acetic acid can completely dissolve carbonate without attacking clay minerals, we designed a comparative experiment, in which carbonate samples were dissolved by 0.5-N acetic acid, 1-N acetic acid, 1-N HCl, 3-N HCl, and concentrated HNO3 and HF. The last treatment completely dissolved both carbonate and siliciclastic components. As shown in Fig. 6, there was no significant difference in Mg/Ca between acetic acid and HCl (Fig. 6a), suggesting that 0.5-N acetic acid completely dissolved the carbonate components. Furthermore, the brachiopod and marine cement components contained negligible amount of siliciclastic material, as illustrated by extremely low Al content (<0.05%) and Al/Ca (<0.0015) after complete dissolution (Fig. 6b, c). Thus, possible contamination from clay minerals can be confidently excluded in the brachiopod and marine cement components. In contrast, the micrite and mixture components contained some clay minerals. Both Al content (>0.71%) and Al/Ca (>0.020) were more than one order of magnitude higher than those of the brachiopod shell and marine cement components (Fig. 6b, c). However, both Al content and Al/Ca remained low after dissolution by acetic acid or HCl. Although Al content was slightly higher in HCl dissolution, the invariant Mg/Ca implies that dissolution by either acetic acid or HCl did not cause significant Mg release from clay minerals. Therefore, we suggest that 0.5-N acetic acid can completely dissolve the calcareous content in limestone without causing significant contamination from clay minerals.

Dissolution of calcareous content by different type of acids: 0.5-N acetic acid, 1-N acetic acid, 1-N HCl, 3-N HCl and concentrated HF + HNO3 (3:1 in volume ratio). All materials (including siliciclastic and calcareous contents) in carbonate samples were completely dissolved by concentrated HF + HNO3. Element concentrations in solutions were measured by ICP–OES. a Al concentration, b Al/Ca (weight ratio), and c Mg/Ca in solution. Mix mixture component, Mt micrite component, Bra brachiopod component, Ce cement component. Error bars represent 5% uncertainty in ICP–OES analyses

5.2 Diagenetic evaluations

It is widely accepted that isotopic compositions of carbonate rocks can be altered during diagenesis. For example, carbonate carbon and oxygen isotopes are susceptible to diagenetic water–rock interactions (Jacobsen and Kaufman 1999; Knauth and Kennedy 2009; Derry 2010). Recent studies indicate that Mg isotopic compositions of dolomite could be preserved during diagenesis, low-grade metamorphism, and dedolomitization (Jacobson et al. 2010; Geske et al. 2012; Azmy et al. 2013), but δ26Mg of limestones could be diagenetically altered (Fantle and Higgins 2014). Thus, possible diagenetic alteration must be carefully addressed before data interpretation.

Because δ26Mg of marine sediment porewater could be significantly different from that of seawater (Higgins and Schrag 2010; Fantle and Higgins 2014), diagenetic precipitation of authigenic carbonate within sediment porewater would certainly modify the δ26Mg of limestone. Furthermore, authigenic carbonate precipitation is favored in anoxic conditions (Reimers et al. 1996; Sagemann et al. 1999; Schrag et al. 2013), and accordingly tends to incorporate some redox-sensitive elements (such as Mn and Fe), elevating Mn and/or Fe contents in carbonate. Therefore, evaluations of carbonate diagenesis have been approached with cathodoluminescence (CL) and trace element geochemistry.

CL is a fast and efficient technique to evaluate Mn and Fe contents in carbonate qualitatively (Barbin et al. 1991; Budd et al. 2000). CL responses are controlled by the absolute Mn2+ and Fe2+ concentrations and Mn2+/Fe2+ ratio of carbonate (Pierson 1981). Mn2+ stimulates luminescence, while Fe2+ quenches the CL response (Machel 1985; Barbin et al. 1991; Budd et al. 2000). Generally speaking, marine carbonate precipitated from oxic seawater has low Mn2+ and Fe2+ contents and is characterized by nonluminescence. Early diagenetic carbonate formed at shallow sediment depth, in which the mildly reducing porewater has high Mn2+ content and high Mn2+/Fe2+, shows bright luminescence. In contrast, CL of late diagenetic carbonate derived from more reducing porewater (with higher Fe2+ concentration and lower Mn2+/Fe2+) exhibits dull luminescence.

CL can only give a qualitative evaluation of diagenesis (Pierson 1981). A quantitative method is trace element geochemistry. In addition to gaining Mn and Fe, diagenetic alteration of carbonates also involves Sr loss. Diagenetically altered carbonate is normally characterized by low Sr, but high Mn and/or Fe concentrations; thus, high Mn/Sr (>10) may indicate diagenetically altered samples (Jacobsen and Kaufman 1999).

In MHR-3, the brachiopod shell showed nonluminescence (Fig. 7a) and extremely low Mn (1.6 ppm), low Fe (20.8 ppm), and high Sr (1260.4 ppm) contents (Table 3), suggesting the absence of diagenetic alteration. The host rock was characterized by dull luminescence (Fig. 7a), consistent with moderate Fe (765.3 ppm) and Mn (78.3 ppm) concentrations, both of which are beyond the thresholds for quenching and stimulating CL response (Table 3) (Budd et al. 2000). Thus, both CL and trace element data indicate that the host rock has been diagenetically altered, but the high Sr content (567.1 ppm) suggests that diagenetic alteration is subtle.

Cathodoluminescence photomicrographs of the Huangjin limestone. a Nonluminescence of brachiopod shell (Bra) and dull luminescence of the mixture component in host rock (Mix) (MHR-3); b Nonluminescence of marine cements (Cement) within skeletal pores of Rugosa coral and dull luminescence of micritic host rock (Micrite) (MHR-5) Scale bars are 5 mm

In MHR-5 and MHR-7, the majority of marine cement filling in the pore space of the Rugosa coral skeletons was nonluminescent, while the edge near the skeletal material showed dull luminescence (Fig. 7b). This observation is consistent with the low Mn (36.7–52.1 ppm) and Fe (0.6–3.9 ppm) contents of the cements (Table 3). In fact, marine cement is the product of diagenesis. Nonluminescence as well as low Fe and Mn contents imply cementation occurring in oxic seawater, or sediment porewater above the oxic–suboxic redox boundary. Dull luminescence in the edge of cement may be attributed to anaerobic degradation of organic matter attached to coral skeletons, stimulating partial dissolution and reprecipitation of calcite (Meister 2013; Gallagher et al. 2014). The surrounding micritic matrix showed dull luminescence (Fig. 6b) and had moderate Fe (419.6–538.1 ppm) and Mn (161.4–181.4 ppm) contents (Table 3). However, a relatively high Sr (323.6–362.1 ppm) concentration and low Mn/Sr argue against significant diagenetic alteration of micrite.

Possible diagenetic alteration can be further evaluated by C and O isotopes. It is widely accepted that carbonate O is subject to water–rock interactions, resulting in lower δ18O (Knauth and Kennedy 2009; Derry 2010). In contrast, δ13C is less likely altered unless authigenic carbonate precipitation involved oxidation of organic matter (Sass et al. 1991), leading to a positive correlation between δ13C and δ18O. However, there is no correlation between δ13C and δ18O in the Huangjin limestone samples (Fig. 8a, b). Furthermore, δ13C ranged from +0.92‰ to +4.14‰ with an average value of +3.04‰ (n = 23), similar to the composition of Carboniferous seawater (Prokoph et al. 2008). Thus, C and O isotope data also argue against significant contribution from authigenic carbonate precipitation. δ26Mg did not show clear correlation with δ18O (Fig. 8c, d). Marine cement with invariant δ26Mg showed a wide range of δ18O (Fig. 8c). In contrast, the brachiopod shell samples had invariant δ18O but more dispersed δ26Mg (Fig. 8d).

In summary, CL, trace elements, and C and O isotopes demonstrate that the Huangjin limestone samples were not significantly altered during diagenesis.

5.3 Using carbonate to reconstruct seawater Mg isotopic composition

Absence of significant diagenetic alteration of the Huangjin limestone samples implies that Mg isotopes might record the primary seawater signal. Variations in δ26Mg among different carbonate components reflect varying degrees of fractionation during precipitation (Fig. 9). Isotopic composition of component x (δ26Mgx) can be expressed by the following equation:

where x is the identity of the carbonate component (i.e. brachiopod shell, marine cement, micrite, and mixture); and Δx is the isotopic fractionation during component x precipitation. Based on Eq. 2, any carbonate component can be theoretically used to reconstruct δ26Mgsw. However, to be practically suitable, a carbonate component must have: (1) a precisely determined Δx, and (2) a homogeneous isotopic composition. Now, we will evaluate whether the aforementioned four carbonate components can be used to reconstruct δ26Mgsw.

Data are sourced from: 1 Chang et al. (2004), 2 Pogge von Strandmann (2008), 3 Hippler et al. (2009), 4 Ra et al. (2010), 5 Wombacher et al. (2011), 6 Yoshimura et al. (2011), 7 Immenhauser et al. (2010), 8 Li et al. (2012), 9 Saulnier et al. (2012), 10 Wang et al. (2013)

Mg isotopic fractionation of biogenic carbonate produced by different modern marine organisms and of inorganic carbonate precipitation.

5.3.1 The cement component

Marine cement consists of inorganic carbonate precipitates from seawater (James and Choquette 1983). Mg isotopic fractionation in inorganic carbonate precipitation (Δinorg) has been extensively studied (Galy et al. 2002; Immenhauser et al. 2010; Li et al. 2012; Saulnier et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2013) and experimental studies indicate that Δinorg of HMC is insensitive to temperature, pH, and Mg/Ca of solutions, and ranges from 2.2‰ to 2.7‰ (Li et al. 2012; Saulnier et al. 2012). A similar range of fractionation (2.2‰–2.7‰) of LMC has been determined in the laboratory (Li et al. 2012), but slightly different values have been obtained from a speleothem study (1.63‰–2.24‰) (Immenhauser et al. 2010) and from another laboratory synthesis experiment (1.9‰–3.2‰) (Saulnier et al. 2012). The latter work also demonstrated that Δinorg of LMC is sensitive to precipitation rate (Saulnier et al. 2012). Δinorg of aragonite precipitation is temperature-dependent, and is significantly smaller than that of calcite precipitation (0.95 at 25 °C) (Wang et al. 2013). Besides, theoretical calculations yield a large variation in Δinorg, and many theoretical calculations have shown opposite fractionation as compared with field and laboratory studies (i.e. enrichment of 26Mg in carbonate minerals) (Rustad et al. 2010; Schauble 2011; Pinilla et al. 2015). Moreover, it has been proposed that the lattice structure of carbonate minerals have a significant impact on Mg isotope fractionation. Increasing Mg/Ca, (i.e. calcite to dolomite), changing the lattice structure, and decreasing mean Mg–O bond length favor enrich the heavy Mg isotope (Wang et al. 2017). Overall, current estimates of Δinorg are far from precise enough to allow accurate determination of δ26Mgsw (Fig. 9). Further work should reduce the uncertainty of Δinorg (Pierson 1981; James and Choquette 1983; Machel 1985; Budd et al. 2000; Higgins and Schrag 2010).

Four measurements of the pure marine cements collected from the pore-filling of Rugosa skeletons had nearly identical δ26Mg, ranging from −3.40‰ to −3.54‰ (average = −3.47‰. SD = 0.07‰, n = 4). δ26Mg for six mixed samples that also contained coral skeletal materials showed wider variation (between −3.27‰ and −3.75‰; average = −3.58‰, SD = 0.16‰, n = 6), probably due to diagenetic alteration of coral skeletons (showing dull luminescence) or possible vital effect during coral growth (see Fig. 8e). Homogeneous isotopic compositions of marine cement imply that this component might be used to reconstruct δ26Mgsw. Although precise determination of δ26Mgsw was not possible due to large uncertainties in Δinorg, the stratigraphic trend of δ26Mgsw may be recovered by measuring a series of marine cements from different horizons (assuming invariant Δinorg).

Importantly, not all cements are precipitated directly from seawater. Cementation also occurs in sediments (i.e. burial cements), accordingly recording the porewater signals. It is well known that porewater Mg isotopic composition (δ26Mgpw) can be different from δ26Mgsw due to authigenic mineral formation (Higgins and Schrag 2010). Analyses of burial cements would yield porewater rather than seawater Mg isotopic compositions. Therefore, marine or burial cements should be differentiated by various petrographic and geochemical analyses, such as CL and trace element geochemistry (Pierson 1981; James and Choquette 1983; Machel 1985; Budd et al. 2000). Marine cement precipitated from oxic seawater is characterized by nonluminescence and low Fe and Mn contents, while burial cement formed in suboxic/anoxic sediment porewater can be identified by dull to bright luminescence and high Fe and/or Mn concentrations.

5.3.2 The brachiopod shell component

Carbon and oxygen isotopes of brachiopod shell have been widely used in paleo-environmental studies (Mii et al. 1997, 1999, 2001; Brand et al. 2015), but recent studies indicate that brachiopod shell has heterogeneous C isotopes (Parkinson et al. 2005; Rollion-Bard et al. 2016). Similarly, there is a wide range of variation in δ26Mg within the same shell (Rollion-Bard et al. 2016), although Mg isotopic fractionation of bulk brachiopod shell formation shows a consistent value of ~1.3‰ (Immenhauser et al. 2010; Wombacher et al. 2011) (Fig. 9).

The brachiopod shell component had heterogeneous Mg and C isotope compositions (Figs. 5a, b, 8). The thickened hinge area in the pedicle valve had higher δ13C and lower δ26Mg than the unspecified areas in both pedicle and brachial valves, and there was a crude negative correlation between δ26Mg and δ13C (Fig. 8f) (Rollion-Bard et al. 2016). Heterogeneous Mg isotopic composition in brachiopod shell may be attributed to a kinetic effect related to brachiopod growth (Rollion-Bard et al. 2016), and the crude correlation between δ26Mg and δ13C implies biological fractionation in C and Mg isotopes might be controlled by similar factors. Therefore, brachiopod shell might be used to reconstruct δ26Mgsw only after further assessment of locality-specific fractionation within brachiopod shell.

5.3.3 The mixture component

The mixture component contained bioclasts and lime mud (Fig. 3b). Because fractionation of biogenic carbonate varies (Pogge von Strandmann 2008; Immenhauser et al. 2010; Wombacher et al. 2011) (Fig. 9), mixing of different types of biogenic carbonate grains would result in the variation of isotopic composition. Furthermore, micrite derives from different sources (see 5.3.4), and its δ26Mg also depends on the origin of the lime mud. Therefore, we suggest that the mixture component (or the bulk carbonate samples) cannot be used to reconstruct δ26Mgsw. This conclusion is supported by a 0.3‰ difference (−3.49‰ and −3.17‰) between the two samples of mixture component collected from the same specimen.

5.3.4 The micrite component

The four micrite samples from two specimens (MHR-5 and MHR-7) had similar isotopic compositions, ranging from −2.86‰ to −2.97‰ (average = 2.93‰, SD = 0.05‰, n = 4), suggesting the potential application of micrite to reconstruct δ26Mgsw. Micrite occurs in all types of non-reef carbonates except for carbonate grainstone (Folk 1959; Tucker and Wright 1990). It accounts for >90vol% in lime mudstone, >50vol% in wackstone, and a variable amount in packstone. In addition, many reef carbonates contain substantial amounts of micrite. Because of its homogeneous composition (i.e. without carbonate grains), lime mudstone has been widely used as the premium material for carbon isotope analysis.

Micrite can derive from multiple carbonate sources. In the modern ocean, micrite is mainly produced by disarticulation of weakly calcified algae (e.g., Helimida), which produce a large quantity of aragonite needles in the tropical shallow marine environment. In addition, small amounts of micrite derive from mechanical abrasion and biological erosion of carbonate grains as well as from direct precipitation from seawater with or without the aid of microbial activity (Munnecke and Samtleben 1996). In the geological past when calcified algae were rare or absent (Verbruggen et al. 2005), micrite was dominantly sourced from micritization of pre-existing carbonate grains (e.g. fossil skeletons), precipitation from inorganic seawater, or induced precipitation by calcified bacteria (Riding 1991; Kaźmierczak et al. 1996). Because Mg isotope fractionation for inorganic carbonate precipitation is mineralogy dependent (Li et al. 2012; Saulnier et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2013) and biogenic carbonate formation has a significant vital effect (Pogge von Strandmann 2008; Hippler et al. 2009; Immenhauser et al. 2010) (Fig. 9), the isotopic composition of micrite might be highly variable and source-dependent. Therefore, we speculate that micrite is not a suitable material to reconstruct δ26Mgsw.

To further test the isotopic homogeneity of micrite, we compared the isotopic composition of the micrite component in MHR-5 and MHR-7 with that of the micrite fraction in the mixture component of MHR-3. The mixed sample in MHR-3 was composed of 60% micrite, 15% foraminifera testa, and 15% brachiopod fragments (Fig. 3b). Mg isotopic composition of the mixture component (\(\updelta^{26} {\text{Mg}}_{\text{mix}}\)) can be expressed by the mixing of three carbonate fractions:

where f i is the mass fraction of i; and subscripts mt, bra, and foram represent micrite, brachiopod shell fragment, and foraminifera testa, respectively. The isotopic composition of Carboniferous foraminifera (δ26Mgforam) is unknown, but can be inferred from modern foraminifera testa consisting of HMC. Fractionation of modern HMC foraminifera ranges from 1.5‰ to 2.9‰ (Fig. 9), which is 0.2‰ to 1.6‰ larger than that of the brachiopod shell formation (1.3‰). Thus, we can assign −2.4‰ and −2.6‰ to −3.7‰ for δ26Mgbra and δ26Mgforam, respectively. From Eq. 3, δ26Mgmt ranges from −3.6‰ to −3.9‰ and from −3.2‰ to −3.5‰ for the micrite fraction in the mixture component of MHR-3. These values are significantly lower than δ26Mg of the micrite component in MHR-5 and MHR-7 (−2.9‰). Therefore, this calculation confirms that the micrite is not suitable to reconstruct δ26Mgsw. This could be further tested by the analysis of micrite samples from multiple correlatable sections.

In summary, because of the heterogeneous Mg isotopic composition in limestone, reconstruction of δ26Mgsw should use an individual carbonate component instead of bulk carbonate samples. None of the four investigated carbonate components in this study were suitable to precisely reconstruct δ26Mgsw. Although marine cement is the most promising candidate, precise determination of δ26Mgsw requires accurate measurement of Δinorg. At the same time, precise recognition of marine cement types by various petrological and geochemical techniques is prerequisite for the study. Also, the carbonate precipitate temperature needs to be reconstructed by other analysis. Both the brachiopod shell and the mixture components had heterogeneous isotopic compositions, precluding their use in reconstructing δ26Mgsw. Although micrite has been widely used in geochemical analyses, multiple sources of lime mud prevent its application to reconstructing δ26Mgsw.

5.4 Effect of biogenic carbonate composition on δ26Mgsw

Fluctuation in δ26Mgsw reflects variations of the inputs and outputs of Mg in the ocean (Wilkinson and Algeo 1989; Mackenzie and Morse 1992). Continental weathering is the only important Mg source for seawater (Tipper et al. 2006a, b; Tipper et al. 2008), with river water delivering an estimated 4.0–4.7 Tmol/year Mg into the modern ocean (Higgins and Schrag 2015). River water Mg isotopic composition (δ26Mgrw) in an individual river is determined by the lithology of the drainage area and the intensity of chemical weathering (Tipper et al. 2006b; Pogge von Strandmann et al. 2008; Wimpenny et al. 2011). At the global scale, δ26Mgrw is mainly controlled by the relative fraction of Mg derived from carbonate and silicate rocks.

There are two major sinks for seawater Mg: hydrothermal reaction and carbonate formation (Mackenzie and Morse 1992). Hydrothermal reaction accounts for more than half of the Mg sink in the modern oceans (2.0–3.1 Tmol/year), while carbonate precipitation consumes 0.75–1.0 Tmol/year seawater Mg (Higgins and Schrag 2015). In terms of isotope fractionation, high-temperature hydrothermal reactions are associated with negligible fractionation (Beinlich et al. 2014), while low-temperature hydrothermal processes are associated with limited fractionation associated with preferential scavenging of heavy Mg from seawater (Higgins and Schrag 2010, 2015). In contrast, carbonate precipitation is associated with significant fractionation (up to 5‰) by preferential utilization of 24Mg (Fig. 9).

The impact of marine carbonate formation on δ26Mgsw is complicated by (1) the amount of carbonate production, (2) dolomite abundance, and (3) the composition of biogenic carbonate. There is no doubt that greater carbonate production and dolomite abundance would result in higher δ26Mgsw, but it is unclear how δ26Mgsw is affected by the composition of biogenic carbonate. We speculate that biogenic carbonate composition might cause substantial variation in δ26Mgsw for the following reasons. First, biogenic carbonate accounts for more than 90% of marine carbonate production in Phanerozoic oceans (Tucker and Wright 1990). Second, carbonate-secreting organisms can variably fractionate Mg isotope (Fig. 9). Third, the original signals might be preserved in carbonate rocks, as suggested by the heterogeneous isotopic composition of the Huangjin limestone. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the extent of the impact on δ26Mgsw resulting from secular variation of biogenic carbonate sources (Stanley and Hardie 1999).

In the modern ocean, carbonate sinks for seawater Mg and Ca are 0.75–1.0 and 14.5–17.0 Tmol/year, respectively (Higgins and Schrag 2015). If Mg/Ca (mol/mol) ratios for dolomite and limestone are 1 and 0.02, respectively, (Table 1), the limestone (or biogenic carbonate) sink for seawater Mg is estimated to be 0.29–0.34 Tmol/year, accounting for 29%–45% of the carbonate sink and 6%–8% of the marine Mg sink (Holland 2005; Higgins and Schrag 2015). The long-term steady-state isotopic mass balance of seawater Mg can be expressed as follows:

where f x is the mass fraction of sink x, and subscripts HHR, LHR, bc, and dol refer to high-temperature hydrothermal reaction, low-temperature hydrothermal reaction, biogenic carbonate precipitation, and dolomite formation, respectively.

Because carbonate-secreting organisms can variably fractionate Mg isotopes (ranging from 0.2‰ to 4.8‰, Fig. 9), δ26Mgbc is controlled by the community structures of carbonate-secreting organisms. The global average fractionation for biogenic Ca-carbonate (Δbc) can be calculated by the weighted average of all types of biogenic carbonate:

where M i bc and \(\Delta _{bc}^{i}\) are the mass and isotopic fractionation of biogenic carbonate component i.

We can use the early Carboniferous Huangjin Formation as an example to quantify how δ26Mgsw is affected by the community structure of carbonate-secreting organisms. The marine invertebrate fossil assemblage in the Carboniferous is represented by the Paleozoic Fauna, dominated by brachiopod, crinoids, coral, and bryozoan (Sepkoski and Miller 1985). In the Huangjin Formation, brachiopods and Rugosa corals are the two dominant carbonate-secreting fossil groups. In calculations, \(\Delta _{bc}^{brachiopod}\) and \(\Delta _{bc}^{coral}\) are set to 1.2‰ and 2.6‰, respectively, (Pogge von Strandmann 2008; Hippler et al. 2009; Wombacher et al. 2011; Yoshimura et al. 2011), which allows Δbc to have a similar range of variation. Further assuming that biogenic carbonate formation accounts for 7% (fbc = 0.07) of the Mg sink in seawater, change from a brachiopod-dominant fauna to a Rugosa-dominant fauna would result in ~0.1‰ increase in δ26Mgsw. Considering ~5‰ variations in the fractionation of biogenic carbonate (Fig. 9), fauna turnover could cause a maximum of 0.3‰ fluctuation in δ26Mgsw. Therefore, δ26Mgsw is only slightly affected by the composition of carbonate-secreting organisms, because of a small biogenic carbonate sink in the modern ocean.

However, an increase in the biogenic carbonate sink, would magnify the isotopic effect of biogenic carbonate composition, resulting in a larger impact on δ26Mgsw. When f bc increases to 16% (as compared with the modern value of 6%–8%), fauna composition change would cause as much as 0.7‰ variation in δ26Mgsw (Fig. 10a). On the other hand, increases in f dol , f HHT , and f LHT would dampen such an effect (Fig. 10b–d). Moreover, considering the constant slope, the isotopic effect imposed by the turnover of carbonate-secreting organisms is not affected by δ26Mgrw, Δ26MgLHT, or Δ26Mgdol (Fig. 10e, f), but δ26Mgsw is significantly affected by δ26Mgrw (Fig. 10e).

Mass balance modeling results showing how δ26Mgsw is affected by Δ26Mgbc. Contour lines in each figure represent various values of a fbc; b Δ26Mgdol; c fHHT; d fLHT; e δ26Mgrw; and f Δ26MgLHT. The dashed line represents isotopic composition of modern seawater. The default values are fHHT = 0.4, fLHT = 0.32, fbc = 0.1, fdol = 0.18, δ26Mgrw = −1.1‰, Δ26MgLHT = −0.7‰, Δ26Mgdol = 2‰

6 Conclusions

Mg isotopic compositions of the four carbonate components recognized in the limestone of early Carboniferous Huangjin Formation have different Mg isotopic compositions. Such isotopic differences reflect various degrees of fractionation during carbonate formation. None of the four investigated carbonate components can be used to precisely determine δ26Mgsw at the current stage. Marine cement had homogeneous δ26Mg, but precise determination of δ26Mgsw was prevented by large uncertainties in the fractionation of inorganic carbonate precipitation. At the same time, precise recognition of marine cement by various petrographic and geochemical methods is required for the study. Neither the micrite nor the mixture component is a suitable material, because both lime mud and carbonate grains could be derived from multiple sources. Although brachiopod shell was regarded as the ideal material for carbon isotope analyses, both C and Mg isotopes showed wide variation, suggesting a significant vital effect during brachiopod growth. There is a wide range in the fractionation of biogenic carbonate formation, and heterogeneous Mg isotopic compositions of the Huangjin limestone imply that such isotopic variation could be preserved in rock records. Therefore, bulk carbonate/calcareous sediment cannot be used to reconstruct δ26Mgsw. In addition, δ26Mgsw is only slightly affected by the fauna composition of carbonate-secreting organisms, when the biogenic carbonate sink is small.

References

Azmy K, Lavoie D, Wang Z, Brand U, Al-Aasm I, Jackson S, Girard I (2013) Magnesium-isotope and REE compositions of Lower Ordovician carbonates from eastern Laurentia: implications for the origin of dolomites and limestones. Chem Geol 356:64–75

Barbin V, Ramseyer K, Debenay JP, Schein E, Roux M, Decrouez D (1991) Cathodoluminescence of recent biogenic carbonates: an enviromental and ontogenetic fingerprint. Geol Mag 128:19–26

Beinlich A, Mavromatis V, Austrheim H, Oelkers EH (2014) Inter-mineral Mg isotope fractionation during hydrothermal ultramafic rock alteration—implications for the global Mg-cycle. Earth Planet Sci Lett 392:166–176

Brand U et al (2015) Carbon isotope composition in modern brachiopod calcite: a case of equilibrium with seawater? Chem Geol 411:81–96

Budd DA, Hammes U, Ward WB (2000) Cathodoluminescence in calcite cements: new insights on Pb and Zn sensitizing, Mn activation, and Fe quenching at low trace-element concentrations. J Sediment Res 70:217–226

Chang VTC, Williams RJP, Makishima A, Belshawl NS, O’Nions RK (2004) Mg and Ca isotope fractionation during CaCO3 biomineralisation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 323:79–85

Chen Z, Sun Y (2013) Discovery of color patterned Cranaena (Brachiopoda) from the lower Carboniferous Huangjin Formation in Guilin of Guangxi with a brief comment on its geological and stratigraphic distribution. J Palaeogeogr 15:797–810

Derry LA (2010) On the significance of δ13C correlations in ancient sediments. Earth Planet Sci Lett 296:497–501

Elderfield H, Schultz A (1996) Mid-ocean ridge hydrothermal fluxes and the chemical composition of the ocean. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 24:191–224

Fantle MS, Higgins J (2014) The effects of diagenesis and dolomitization on Ca and Mg isotopes in marine platform carbonates: implications for the geochemical cycles of Ca and Mg. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 142:458–481

Folk R (1959) Practical petrographic classification of limestones. AAPG Bull 43:1–38

Gallagher KL, Dupraz C, Visscher PT (2014) Two opposing effects of sulfate reduction on carbonate precipitation in normal marine, hypersaline, and alkaline environments: COMMENT. Geology 42:e313–e314

Galy A, Bar-Matthews M, Halicz L, O’Nions RK (2002) Mg isotopic composition of carbonate: insight from speleothem formation. Earth Planet Sci Lett 201:105–115

Galy A et al (2003) Magnesium isotope heterogeneity of the isotopic standard SRM980 and new reference materials for magnesium-isotope-ratio measurements. J Anal At Spectrom 18:1352–1356

Geske A, Zorlu J, Richter DK, Buhl D, Niedermayr A, Immenhauser A (2012) Impact of diagenesis and low grade metamorphosis on isotope (δ26Mg, δ13C, δ18O and 87Sr/86Sr) and elemental (Ca, Mg, Mn, Fe and Sr) signatures of Triassic sabkha dolomites. Chem Geol 332–333:45–64

Hance L, Hou H, Vachard D (2011) Upper Famennian to Visean Foraminifers and some carbonate Microproblematica from South China-Hunan, Gruangxi and Guizhou. Geological Publishing House, Beijing

Hardie LA (1996) Secular variation in seawater chemistry: an explanation for the coupled secular variation in the mineralogies of marine limestones and potash evaporites over the past 600 my. Geology 24:279–283

Higgins JA, Schrag DP (2010) Constraining magnesium cycling in marine sediments using magnesium isotopes. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 74:5039–5053

Higgins JA, Schrag DP (2015) The Mg isotopic composition of Cenozoic seawater—evidence for a link between Mg-clays, seawater Mg/Ca, and climate. Earth Planet Sci Lett 416:73–81

Hippler D, Buhl D, Witbaard R, Richter DK, Immenhauser A (2009) Towards a better understanding of magnesium-isotope ratios from marine skeletal carbonates. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 73:6134–6146

Holland HD (2005) Sea level, sediments and the composition of seawater. Am J Sci 305:220–239

Huang K-J et al (2015) Magnesium isotopic compositions of the Mesoproterozoic dolostones: implications for Mg isotopic systematics of marine carbonate. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 164:333–351

Immenhauser A, Buhl D, Richter D, Niedermayr A, Riechelmann D, Dietzel M, Schulte U (2010) Magnesium-isotope fractionation during low-Mg calcite precipitation in a limestone cave—field study and experiments. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 74:4346–4364

Jacobsen SB, Kaufman AJ (1999) The Sr, C and O isotopic evolution of Neoproterozoic seawater. Chem Geol 161:37–57

Jacobson AD, Zhang Z, Lundstrom C, Huang F (2010) Behavior of Mg isotopes during dedolomitization in the Madison Aquifer, South Dakota. Earth Planet Sci Lett 297:446–452

James NP, Choquette PW (1983) Diagenesis 6. Limestones—the sea floor diagenetic environment. Geosci Can 10:162–179

Kaźmierczak J, Coleman ML, Gruszczyński M, Kempe S (1996) Cyanobacterial key to the genesis of micritic and peloidal limestones in ancient seas. Acta Palaeontol Pol 41:319–338

Knauth LP, Kennedy MJ (2009) The late Precambrian greening of the Earth. Nature 460:728–732

Li C et al (2012) Evidence for a redox stratified Cryogenian marine basin, Datangpo Formation, South China. Earth Planet Sci Lett 331–332:246–256

Machel HG (1985) Cathodoluminescence in calcite and dolomite and its chemical interpretation. Geosci Canada 12:1–9

Mackenzie FT, Morse JW (1992) Sedimentary carbonates through Phanerozoic time. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 56:3281–3295

Meister P (2013) Two opposing effects of sulfate reduction on carbonate precipitation in normal marine, hypersaline, and alkaline environments. Geology 41:499–502

Mii HS, Grossman EL, Yancey TE (1997) Stable carbon and oxygen isotope shifts in Permian seas of West Spitsbergen; global change or diagenetic artifact? Geology 25:227–230

Mii HS, Grossman EL, Yancey TE (1999) Carboniferous isotope stratigraphies of North America: implications for Carboniferous paleoceanography and Mississippian glaciation. Geol Soc Am Bull 111:960–973

Mii HS, Grossman EL, Yancey TE, Chuvashov B, Egorov A (2001) Isotopic records of brachiopod shells from the Russian Platform—evidence for the onset of mid-Carboniferous glaciation. Chem Geol 175:133–147

Munnecke A, Samtleben C (1996) The formation of micritic limestones and the development of limestone-marl alternations in the Silurian of Gotland, Sweden. Facies 34:159–176

Opfergelt S, Georg RB, Delvaux B, Cabidoche YM, Burton KW, Halliday AN (2012) Mechanisms of magnesium isotope fractionation in volcanic soil weathering sequences, Guadeloupe. Earth Planet Sci Lett 341–344:176–185

Parkinson D, Curry GB, Cusack M, Fallick AE (2005) Shell structure, patterns and trends of oxygen and carbon stable isotopes in modern brachiopod shells. Chem Geol 219:193–235

Peng Y et al (2016) Constraining dolomitization by Mg isotopes: a case study from partially dolomitized limestones of the middle Cambrian Xuzhuang Formation, North China. Geochem Geophys Geosyst. doi:10.1002/2015gc006057

Pierson BJ (1981) The control of cathodoluminescence in dolomite by iron and manganese. Sedimentology 28:601–610

Pinilla C, Blanchard M, Balan E, Natarajan SK, Vuilleumier R, Mauri F (2015) Equilibrium magnesium isotope fractionation between aqueous Mg2+ and carbonate minerals: insights from path integral molecular dynamics. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 163:126–139

Pogge von Strandmann PAE (2008) Precise magnesium isotope measurements in core top planktic and benthic foraminifera. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 9:1–13

Pogge von Strandmann PAE, Burton KW, James RH, van Calsteren P, Gislason SR, Sigfússon B (2008) The influence of weathering processes on riverine magnesium isotopes in a basaltic terrain. Earth Planet Sci Lett 276:187–197

Pogge von Strandmann PAE, Elliott T, Marschall HR, Coath C, Lai Y-J, Jeffcoate AB, Ionov DA (2011) Variations of Li and Mg isotope ratios in bulk chondrites and mantle xenoliths. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 75:5247–5268

Prokoph A, Shields GA, Veizer J (2008) Compilation and time-series analysis of a marine carbonate δ18O, δ13C, 87Sr/86Sr and δ34S database through Earth history. Earth Sci Rev 87:113–133

Ra K, Kitagawa H, Shiraiwa Y (2010) Mg isotopes and Mg/Ca values of coccoliths from cultured specimens of the species Emiliania huxleyi and Gephyrocapsa oceanica. Mar Micropaleontol 77:119–124

Reimers CE, Ruttenberg KC, Canfield DE, Christiansen MB, Martin JB (1996) Porewater pH and authigenic phases formed in the uppermost sediments of the Santa Barbara Basin. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 60:4037–4057

Riding R (1991) Classification of microbial carbonates. In: Riding R (ed) Calcareous algae and stromatolites. Springer, Berlin, pp 21–87

Rollion-Bard C, Saulnier S, Vigier N, Schumacher A, Chaussidon M, Lécuyer C (2016) Variability in magnesium, carbon and oxygen isotope compositions of brachiopod shells: implications for paleoceanographic studies. Chem Geol 423:49–60

Rustad JR et al (2010) Isotopic fractionation of Mg2+(aq), Ca2+(aq), and Fe2+(aq) with carbonate minerals. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 74:6301–6323

Sagemann J, Bale SJ, Briggs DEG, Parkes RJ (1999) Controls on the formation of authigenic minerals in association with decaying organic matter: an experimental approach. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 63:1083

Sass E, Bein A, Almogi-Labin A (1991) Oxygen-isotope composition of diagenetic calcite in organic-rich rocks: evidence for 18O depletion in marine anaerobic pore water. Geology 19:839–842

Saulnier S, Rollion-Bard C, Vigier N, Chaussidon M (2012) Mg isotope fractionation during calcite precipitation: an experimental study. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 91:75–91

Schauble EA (2011) First-principles estimates of equilibrium magnesium isotope fractionation in silicate, oxide, carbonate and hexaaquamagnesium(2+) crystals. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 75:844–869

Schrag DP, Higgins JA, Macdonald FA, Johnston DT (2013) Authigenic carbonate and the history of the global carbon cycle. Science 339:540–543

Sepkoski JJ Jr, Miller AI (1985) Evolutionary faunas and the distribution of Paleozoic benthic communities. In: Valentine JW (ed) Phanerozoic diversity patterns: profiles in macroevolution. Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp 153–190

Shen B, Jacobsen B, Lee C-TA, Yin Q-Z, Morton DM (2009) The Mg isotopic systematics of granitoids in continental arcs and implications for the role of chemical weathering in crust formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106:20652–20657

Shen B, Wimpenny J, Lee C-TA, Tollstrup D, Yin Q-Z (2013) Magnesium isotope systematics of endoskarns: implications for wallrock reaction in magma chambers. Chem Geol 356:209–214

Stanley SM, Hardie LA (1998) Secular oscillations in the carbonate mineralogy of reef-building and sediment-producing organisms driven by tectonically forced shifts in seawater chemistry. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 144:3–19

Stanley SM, Hardie LA (1999) Hypercalcification: paleontology links plate tectonics and geochemistry to sedimentology. GSA Today 9:1–7

Stanley SM, Ries JB, Hardie LA (2010) Increased production of calcite and slower growth for the major sediment-producing alga Halimeda as the Mg/Ca ratio of seawater is lowered to a “Calcite Sea” level. J Sediment Res 80:6–16

Teng F-Z et al (2015) Magnesium isotopic compositions of international geological reference materials. Geostand Geoanal Res 39:329–339

Tipper ET, Galy A, Bickle MJ (2006a) Riverine evidence for a fractionated reservoir of Ca and Mg on the continents: implications for the oceanic Ca cycle. Earth Planet Sci Lett 247:267–279

Tipper ET, Galy A, Gaillardet J, Bickle MJ, Elderfield H, Carder EA (2006b) The magnesium isotope budget of the modern ocean: constraints from riverine magnesium isotope ratios. Earth Planet Sci Lett 250:241–253

Tipper ET, Galy A, Bickle MJ (2008) Calcium and magnesium isotope systematics in rivers draining the Himalaya–Tibetan-Plateau region: lithological or fractionation control? Geochim Cosmochim Acta 72:1057–1075

Tucker ME, Wright VP (1990) Carbonate Sedimentology. Blackwell Scientific, Oxford

Verbruggen H, Clerck OD, Schils T, Kooistra WHCF, Coppejans E (2005) Evolution and phylogeography of Halimeda section Halimeda (Bryopsidales, Chlorophyta). Mol Phylogenet Evol 37:789–803

Wang Z, Hu P, Gaetani G, Liu C, Saenger C, Cohen A, Hart S (2013) Experimental calibration of Mg isotope fractionation between aragonite and seawater. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 102:113–123

Wang W, Qin T, Zhou C, Huang S, Wu Z, Huang F (2017) Concentration effect on equilibrium fractionation of Mg–Ca isotopes in carbonate minerals: insights from first-principles calculations. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 208:185–197

Wilkinson BH, Algeo TJ (1989) Sedimentary carbonate record of calcium–magnesium cycling. Am J Sci 289:1158–1194

Wimpenny J, Burton KW, James RH, Gannoun A, Mokadem F, Gíslason SR (2011) The behaviour of magnesium and its isotopes during glacial weathering in an ancient shield terrain in West Greenland. Earth Planet Sci Lett 304:260–269

Wombacher F, Eisenhauer A, Böhm F, Gussone N, Regenberg M, Dullo WC, Rüggeberg A (2011) Magnesium stable isotope fractionation in marine biogenic calcite and aragonite. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 75:5797–5818

Xiao S et al (2004) The Neoproterozoic Quruqtagh Group in eastern Chinese Tianshan: evidence for a post-Marinoan glaciation. Precambrian Res 130:1–26

Yoshimura T, Tanimizu M, Inoue M, Suzuki A, Iwasaki N, Kawahata H (2011) Mg isotope fractionation in biogenic carbonates of deep-sea coral, benthic foraminifera, and hermatypic coral. Anal Bioanal Chem 401:2755–2769

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (41272017, 41322021, and 41172001) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2014M55006). We also thank Professor Fangzhen Teng for Mg isotope analysis at University of Washington and Professor Chuanming Zhou for C and O isotope analyses at Nanjing Institutes of Geology and Paleontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, H., Xu, Y., Huang, K. et al. Heterogeneous Mg isotopic composition of the early Carboniferous limestone: implications for carbonate as a seawater archive. Acta Geochim 37, 1–18 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11631-017-0179-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11631-017-0179-x