Abstract

Through theory of narcissism and leisure constraint theory, this study considers how tourists’ vulnerable narcissism facets and lack of interest travel constraint at destination level affect their interest in attractions after viewing social media photographs of other visitors posed as full shot or medium shot (photograph types). Partial least-squares analysis on 614 survey returns (307 for full-shot and 307 for medium-shot photographs) revealed vulnerable narcissism’s impact on attraction visit interest is mostly evident in wenqing attractions. Lack of interest constraint lowers natural and monument attraction visit interest but not for wenqing attractions. Only entitlement rage facet positively influences lack of interest constraint.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Photography plays a very important role in the tourism sector and shapes destination image (Bassols-Gardella and Coromina 2022). When touring tourist destinations, which often has “a number of individual attractions together with the support services required by tourists” (Swarbrooke 2002, p. 9), visitors often take photographs with the attractions and upload them on social media (Trpkovski et al. 2018). Such visitor-captured photographs are often seen, admired, and imitated by those who view the photographs. Thus, social media is known to play an important role in influencing others (Lebrun et al. 2022) and also tourism marketing (Armutcu et al. 2023). This photo-related behavior is also in line with the trend that tourism photography has increasingly shifted from capturing extraordinary scenes to the objectification of places and people (Urry and Larsen 2011) and production of social relationship. Such visitor-captured photographs have images of visitors with the attraction as the background (Christou et al. 2020). Full shots show the full body of the visitor but with the attraction environment forming a large and main part of the background (Jasen 2018). By contrast, medium shots place greater emphasis on the visitor by showing the visitor from the waist up while revealing lesser portion of the attraction as the backdrop (Thompson and Bowen 2009).

Tourists’ behaviors are influenced by their interpretation of the photographs (Kim and Stepchenkova 2015; Taecharungroj and Mathayomchan 2021). However, how potential visitors, upon viewing either full shots or medium shots and imagining posing like the visitors in the photographs, perceive their interest in visiting the destination is not well clarified in extant literature. Furthermore, noting that an attraction’s attractiveness may differ from that of another attraction (although they are within the same destination), this study considers visit interest at the attraction level rather than the often-considered destination level.

A starting point to examine this issue is to note that such photographs are often posted online by visitors for attention grabbing and impression management (Canavan 2017). Thus, narcissists tend to post selfies online for self-promotion (Lee and Sung 2016; Tribe and Mkono 2017). These photographs are then admired and imitated by those who view the photographs. Similarly, when imagining posing like the visitors (i.e., imitating), potential visitors’ narcissism personality trait could affect their interest in the attraction. Furthermore, there could be differences in consequences when potential visitors view full shots and medium shots. A full shot, which emphasizes the attraction more than the visitor, allows the viewers to imagine that they can ride on the attraction’s popularity to make others notice and have a favorable impression of them. A medium shot, which emphasizes the visitor more than the attraction, can make viewers feel others will not miss them and they will receive more attention.

Drawing from theory of narcissism (Pincus and Lukowitsky 2010), this study considers how vulnerable narcissism affects interest in the attraction. This consideration is a response to the call by Christou et al. (2020) for scholars “to use the tourism context to delve deeper into the notion of narcissism and its impacts at a destination and societal level” (p. 289). Except for some studies (Christou et al. 2020; Kim and Jang 2019; Tan and Yang 2021; Tribe and Mkono 2017), academia has paid little attention to the influence of narcissism personality trait on tourism because tourism is often seen in a positive light, but narcissism is viewed as a dark personality trait (Grezo and Adamus 2022; Hollebeek et al. 2022; Turi et al. 2022). Some studies have revealed that narcissism comprises grandiose and vulnerable narcissism (Barnett et al. 2023; Pincus and Lukowitsky 2010). Unlike the often-studied grandiose narcissism, vulnerable narcissism’s empirical testing is still scant (Jauk et al. 2017). To redress this obscurity, this study considers the effect of four vulnerable narcissism’s facets (entitlement rage, devaluing, hiding the self, and contingent self-esteem) on attraction visit interest.

Tourists hold certain preconceived opinions about the destination, such as travel constraints (leisure constraints in the tourism context) when they want to visit the destination. According to leisure constraint theory (Godbey et al. 2010; Jiang et al. 2020), constraints are reasons (or possibly excuses) that prevent or limit leisure activity participation (Jackson 2000). Little is known about how vulnerable narcissism affects travel constraint. This study considers this issue through the constraint of lack of interest in the destination.

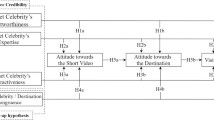

Thus, by drawing from and combining narcissism (Pincus and Lukowitsky 2010) and leisure constraint theories (Godbey et al. 2010; Jiang et al. 2020) and comparing full shots and medium shots, this study considers how tourists’ four vulnerable narcissism facet personality traits (contingent self-esteem, devaluing, entitlement rage, and hiding the self) affect lack of interest constraint at destination level, and how they then affect their attraction visit interest after viewing photographs uploaded on social media. The research model is shown in Fig. 1.

This study contributes to the literature and filling the gaps by first examining the under-studied role of narcissism in tourism (Christou et al. 2020; Tan and Yang 2021; Tribe and Mkono 2017) and, second, dwelling on the relatively unknown vulnerable narcissism at its facet level (Jauk et al. 2017), which, unlike the often-studied grandiose narcissism, is much less examined. This consideration is important due to the trend that visitor-captured photographs featuring people (Christou et al. 2020) who are posted online are often admired and imitated by others. Third, this could be the only study that considers how vulnerable narcissism and travel constraint collectively affect attraction visit interest, thus contributing to the integration of narcissism and leisure constraint theories. Fourth, by considering the visit interest at the attraction level, this study addresses the gap that many studies have considered visit interest at the destination level. However, the attractiveness of an attraction may differ from that of another attraction although they are within the same destination. Fifth, this study has managerial implications since travel photograph-taking, which involves objectification of places or people, is deeply intertwined with tourism industry (Crawshaw and Urry 1997; Deng and Liu 2021; Park and Kim 2018; Ren et al. 2021). Photograph is crucial for destination marketing organizations (DMOs) (Taylor 2020) because such photographs are often placed on social media, an important media for tourists to express their travel experience and an often-used tool for others to do travel planning (Nolasco-Cirugeda et al. 2022). Photograph also shapes the image others have about the destination (Taecharungroj and Mathayomchan 2021) and generates a virtuous process of hermeneutic circle (Robinson 2014; Urry and Larsen 2011) where “tourists visit sites made famous in the images in tourist brochures, take and share photos replicating these images and reinforcing presented place myths” (Pearce and Moscardo 2015, p. 61). Furthermore, although visitor-captured photographs provide a condensed version of destination image, visitors may not faithfully convey the image in their photographs or align the image with that of the DMOs; rather, they present the destinations according to their own perceptions and what others want to see.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the extant literature and develops the hypotheses. Section 3 describes the research method and Sect. 4 provides the results of the data analysis. Section 5 discusses the findings, theoretical implications, practical implications, and research limitations and opportunities for future research.

2 Literature review and hypothesis development

Narcissism personality trait “is characterized by encompassing self-admiration, self-absorption, authority, exhibitionism, superiority, arrogance, exploitation of others, self-sufficiency and extreme vanity” (Riera and Iborra 2023, p 2). Although narcissists feel they are great and desire attention and admiration from others (Casale et al. 2016; Greitemeyer 2022; Lustman et al. 2010; Neave et al. 2020; Riera and Iborra 2023; Velotti et al. 2020), grandiose narcissism involves bold confidence and a domineering attitude (Velotti et al. 2020) but vulnerable narcissism has an avoidance/prevention orientation (Balcerowska and Sawicki 2022) involving neurotic self-doubting who have fragile self-worth that are highly sensitive to others’ appraisals and easily undermined by others (Velotti et al. 2020; Weiss and Miller 2018) and avoiding criticism (Duffy et al. 2023; Weiss and Miller 2018). Vulnerable narcissism comprises four facets (Pincus and Lukowitsky 2010). Entitlement rage refers to expecting others to do as the narcissist wants (such as expressing interest in what narcissist does) and being angry if such expectations are unmet. Devaluing involves devaluing both others and oneself because admiration is absent or feeling self-rebuke because of the need to be recognized by others (Day et al. 2020; Weiss and Miller 2018). Hiding the self refers to unwillingness to let others know about the needs or faults one has, resulting in physical or emotional withdrawal (Day et al. 2020). Contingent self-esteem refers to fragile self-esteem that fluctuates significantly between inferiority and superiority (Naidu et al. 2019). This study focuses on vulnerable narcissism and its facets because unlike grandiose narcissism, vulnerable narcissism remains under-studied, and its empirical testing is still rather scant (Jauk et al. 2017). Facet-level analysis is also useful because past studies have shown that various facets have differential behavioral effects (Naidu et al. 2019).

Leisure constraints are “factors perceived or experienced by individuals who limit the formation of leisure preferences and/or to inhibit or prohibit participation and enjoyment in leisure” (Jackson 2000, p. 62). Since tourism is a leisure activity, leisure constraint theory and travel constraint are often used to understand why tourists do not visit a destination or not as frequently as they want to (Chen et al. 2021). Thus, travel constraint research (Jiang et al. 2020; Tan and Lin 2021) mostly originated from leisure constraint theory. Some travel constraints are lack of interest, companion, money, and time (Jian et al. 2021; Tan and Lin 2021; Yang et al. 2022). Studies have suggested that constraints are context-dependent (Alexandris and Tsorbatzoudis 2002; Chen et al. 2021). Therefore, “the common strategy has been each research group identifying the categories of constraints specific to certain research contexts and/or customizing the instrument development to its own needs” (Godbey et al. 2010, p. 115). This study adopts this approach.

Lack of interest constraint for a destination is considered here because this is an often-mentioned reason or excuse for non-participation or reduced participation (Alexandris et al. 2011; Tan and Liou 2020; Zhang et al. 2012). It is also suggested to be a rationalization of constraints wherein the consequences of other constraints contribute to and ultimately manifest as a lack of interest (Boothby et al. 1981; Davies and Prentice 1995; Fredman and Heberlein 2005; Tan and Kuo 2014).

This study examines how vulnerable narcissism facets influence lack of interest constraint, which is not examined in extant literature. Entitlement rage and devaluing emphasize outward-oriented reactions (Naidu et al. 2019). This study suggests that individuals with high level of entitlement rage, which involves being angry because they are not being noticed by others, are more likely to reason through lack of interest constraint (which originates and involves oneself) to avoid being angry with others. Thus, it is postulated that:

H1a:

Entitlement rage has a positive influence on lack of interest constraint.

To avoid having to devalue oneself or others, those high in the devaluing facet will avoid citing lack of interest constraint, which involves oneself. Hiding the self and contingent self-esteem emphasizes inward-oriented reactions. Hiding the self involves emotional or physical withdrawal (Day et al. 2020) and contingent self-esteem involves fluctuation in self-esteem (Naidu et al. 2019). This study suggests that those being high in these two facets will feel it is less necessary or reluctant to justify, particularly to others, why they do not visit an attraction; that is, they will not cite lack of interest. Thus, this study suggests that contingent self-esteem, devaluing, and hiding the self have no influence on lack of interest constraint. To empirically confirm such relationships, it is postulated that:

H1b:

Contingent self-esteem has a positive influence on lack of interest constraint.

H1c:

Devaluing has a positive influence on lack of interest constraint.

H1d:

Hiding the self has a positive influence on lack of interest constraint.

For a sharper focus (while not losing generalization), this study considers tourist destinations that offer a range of attractions, particularly natural, monument, and wenqing attractions. Akin to English-speaking societies’ hipsters, wenqing (cultured youth) in the Chinese-speaking society prefers arts and a cultured lifestyle while liking to visit small art spaces, bookstores, and cafés (Vermeeren and de Kloet 2020). Wenqing attractions are excellent examples of a tourism structure, which are often man-made or with a huge component of man-made element, created by the tourism industry to direct tourist gaze and are particularly suitable for photograph-taking. They reflect many destinations’ desire to ride on the wenqing trend.

Interest in visiting a particular destination is an often-examined topic (Knollenberg et al. 2020). This study suggests that vulnerable narcissism facets’ influence on tourists’ attraction visit interest is particularly evident in wenqing attractions and less so for other attraction types. Wenqing scenic spots are excellent example of a tourism structure created by tourism industry to direct tourist gaze. Reflecting the current fad of wenqing and with these being “must-see” attractions, tourists (often trend-followers themselves) like these attractions. Visitors also like to upload photographs of themselves taken with the wenqing attraction on social media to show that they are trendy, get others’ attention (Sung et al. 2016), and for self-promotion, which are linked to narcissism personality trait (Bukowski and Samson 2021; Hong et al. 2021; Taylor 2020). Thus, wenqing attractions are aligned with narcissists’ objectives. Given that vulnerable narcissists are sensitive to others’ comments (Jauk et al. 2017), conforming to what the crowd likes by expressing interest in visiting wenqing attraction is a good way to gain others’ approval. This study further suggests that vulnerable narcissism facets have varying effects on attraction visit interest. If individuals are inclined to be angry because others do not pay attention (entitlement rage) or worry that others will disappoint them by not offering admiration (devaluing) (Weiss and Miller 2018), they will feel that wenqing attractions are suitable to avoid being angry or to devalue others or oneself. Thus, entitlement rage and devaluing have a positive influence on wenqing attraction visit interest. Those high in hiding the self, which involves physical or emotional withdrawal (Day et al. 2020), will likely show more interest in natural attractions because they can draw solace in the natural environment. The fluctuating self-esteem associated with contingent self-esteem (Naidu et al. 2019) will likely render the facet being unable to exert, on an overall basis, its influence on attraction visit interest. Hence, it is postulated that while devaluing and entitlement rage positively influence wenqing attraction visit interest, hiding the self positively influences natural attraction visit interest, and contingent self-esteem has no influence on attraction visit interest:

H2a:

Entitlement rage has a positive influence on wenqing attraction visit interest.

H2b:

Devaluing has a positive influence on wenqing attraction visit interest.

H2c:

Hiding the self has a positive influence on natural attraction visit interest.

H2d:

Contingent self-esteem has no influence on attraction visit interest.

Prior research has considered the consequences of leisure constraints, such as participation, motivation, word-of-mou2022th, and enjoyment (Alexandris et al. 2022; Chen et al. 2021; Hubbard and Mannell 2001; Sun et al. ; Tan and Lin 2021), and the results often show negative consequences, such as lowering participation. Lack of interest constraint is a type of intrapersonal constraint, i.e., it originates from oneself and is an internal psychological state (Godbey et al. 2010). It is an often-mentioned reason or excuse for non-participation (Tan and Liou 2020; Zhang et al. 2012). Thus, this study suggests that lack of interest constraint will lower attraction visit interest:

H3:

Lack of interest constraint has a negative influence on attraction visit interest.

Emphasizing the attraction more than the visitor (Jasen 2018), full shots allow viewers to think they can leverage on the attraction’s popularity to gain others’ attention. A medium shot emphasizes the visitor more than a full shot. Thus, medium shots allow viewers to imagine they will be better noticed but at the expense of others having difficulty noticing the attraction. Thus, those who want others’ attention and will be angry if otherwise (entitlement rage) will find riding on the attraction’s popularity a safer bet (as in full shot) than depending on oneself to draw others’ attention (as in medium shot). If the visitor gets more prominent, as in medium shots, devaluing facet may become more exertive, as visitors’ presence will not be easily ignored—thus avoiding the reaction of devaluing oneself and others. Thus, this paper proposes that photograph type (full shot vs. medium shot) moderating the relationship between vulnerable narcissism (entitlement rage and devaluing) and attraction visit interest (H2). However, facets where reactions are inward-oriented (hiding the self and contingent self-esteem) are less likely to be affected by photograph type. Similar to the argument presented in relation to H2, such moderating effect is particularly evident in attractions that are fashionable—that is, wenqing attractions:

H4a:

Photograph type moderates relationship between entitlement rage and wenqing attraction visit interest.

H4b:

Photograph type moderates relationship between devaluing rage and wenqing attraction visit interest.

3 Method

This study considers Hualien, a popular Taiwan tourist destination that offers a wide range of attractions and is away from the major population centers where tourists come from (Fig. 2). Located between Central Mountain Range and Pacific Ocean, Hualien offers natural attractions such as Taroko Gorge (“Grand Canyon” of Taiwan), Qingshui Cliff (a more than 1,000-m cliff that drops almost vertically into the Pacific Ocean), Qixingtan Beach (a half-moon-shaped gulf that opens to the Pacific Ocean), and 48Highland (which offers a wide expanse view of the mountain and ocean). Bisected by Tropic of Cancer and with the East Rift Valley, where Eurasian and Philippine Sea tectonic plates meet, Hualien offers Tropic of Cancer Park and Yuli Junction Monument. Hualien, being populated with aboriginal tribes since pre-historic time, also has aboriginal tribe-related attractions, such as the pre-historic Saoba Stone Pillars. Hualien has numerous wenqing attractions, such as Starbucks Container (comprised of recycled shipping containers stacked on top of one another) and Mr. Sam Café (where building is inspired by and resembles that of fairy tale). The photographs of these nine attractions (one photograph per attraction) were randomly arranged and provided in the questionnaire.

Two questionnaires were designed: a full-shot questionnaire and a medium-shot questionnaire. The constructs, sources, and items are shown in Table 1. The items of both questionnaires were developed by modifying valid scales from past studies (to meet the requirement of content validity) to suit the purpose of this study. Two bilingual professionals who were fluent in English and Chinese were involved in the double translation (English–Chinese–English) protocol because the questionnaires were written in Chinese while the original items were in English. A pre-test was conducted with 10 Taiwanese residents to identify items that were not well-worded which were then modified.

The research assistants approached willing parties personally through convenience sampling at their places of residence, education, or work in Taiwan from April to June 2022. The participants must not be residing, studying, or working in Hualien for inclusion. Once the research assistants ascertained that this inclusion criteria was met, the willing participants were randomly selected to complete ONLY one of the self-administered paper-based questionnaires.

Each questionnaire consisted of four parts. The first part asked respondents the extent to which they possessed vulnerable narcissism facets, which was adopted from the often-used Brief-Pathological Narcissism Inventory (Schoenleber et al. 2015). The second part asked the extent to which lack of interest constraint prevented respondents from touring Hualien or from touring it as much as they desired. The third part contained photographs of nine Hualien’s attractions (one photograph per attraction) arranged randomly and either in full shots (for full-shot questionnaire) or medium shots (for medium-shot questionnaire). Some examples are shown in Fig. 2. Respondents were asked to view one photograph at a time and imagine themselves being in the attraction, posing like the visitor in the photograph, and to post the photograph on their social media. The survey respondents were then asked about the extent of their visit interest for that attraction. Once completed, they were then shown the photograph of next attraction until they have seen all the nine photographs and answered their visit interest for the nine attractions. The fourth part asked about the respondents’ demographics.

The survey respondents expressed their agreement with these items on a five-point Likert scale (1—strongly disagree to 5—strongly agree).

4 Results

A total of 614 responses (307 from full-shot and 307 from medium-shot questionnaires) were obtained (Table 2). Separate exploratory factor analyses were conducted on both questionnaires because there was no standard attraction factor structure. For each group, three factors were obtained: natural, monument, and wenqing attractions (Table 3).

The constructs exhibited reliability and validity, with average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeding 0.5, and internal consistency reliability, with composite reliability (CR) values exceeding 0.7 (Table 4) (Chin 1998). Discriminant validity existed because the square root of the AVE of each construct was larger than the correlation coefficients involving the construct (Fornell and Larcker 1981) (Table 5), and the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) values were below 0.85 (Henseler et al. 2015). Multicollinearity was absent because the highest variance inflation was lower than the threshold value of 5 (Hair et al. 2006). According to independent sample t-test, there was no significant difference in the mean for all constructs (Table 4). Path analysis results using partial least-squares (PLS) method are shown in Table 6 and in pictorial form (Fig. 3) for further clarity.

For full shot, the path analysis revealed that entitlement rage contributes positively to lack of interest constraint (path coefficient = 0.16), thus supporting H1a. H1b, H1c, and H1d are not supported. Thus, as suggested by this study, contingent self-esteem, devaluing, and hiding the self have no influence on lack of interest constraint. Entitlement rage positively influences wenqing attraction visit interest (path coefficient = 0.22). Thus, H2a is supported. Entitlement rage also positively influences monument attraction visit interest (path coefficient = 0.22). Devaluing and contingent self-esteem have no influence on the visit interest of all the three types of attractions. Thus, H2b and H2d are not supported and supported, respectively. As postulated by H2c, hiding the self has a positive influence on natural attraction visit interest (path coefficient = 0.22). Lack of interest constraint has a negative influence on natural attraction (path coefficient = − 0.43) and monument attraction (path coefficient = − 0.25) visit interest. Thus, H3 is partially supported.

For medium shot, the path analysis revealed that entitlement rage contributes positively to lack of interest constraint (path coefficient = 0.31), thus supporting H1a. H1b, H1c, and H1d are not supported. Thus, as suggested by this study, contingent self-esteem, devaluing, and hiding the self have no influence on lack of interest constraint. Entitlement rage negatively influences wenqing attraction visit interest, respectively (path coefficient = − 0.25). Thus, H2a is not supported. Devaluing has a positive influence on wenqing attraction visit interest (path coefficient = 0.24). Thus, H2b is supported. Hiding the self and contingent self-esteem have no influence on the visit interest of all the three types of attractions. Thus, H2c and H2d are not supported and supported, respectively. Lack of interest constraint has a negative influence on natural attraction (path coefficient = − 0.44) and monument attraction (path coefficient = − 0.28) visit interest. Thus, H3 is partially supported.

Measurement model invariance was assessed using the measurement invariance of the composite models (MICOM) approach (Henseler et al. 2016). The results (please see Table 7 for details) revealed that compositional invariance, equality of means, and equality of variances were established, thus confirming full invariance and performing PLS multigroup analysis was appropriate. Multigroup analysis conducted using MGA method (Henseler et al. 2009) was used to determine whether significant difference in the path coefficients of the two groups exists for each path. The analysis showed that path coefficients were significantly different for two paths across the two groups: devaluing→wenqing attractions [path coefficient: full shot = − 0.16 (not significant); medium shot = 0.24 (significant)] and entitlement rage→wenqing attractions [path coefficient: full shot = 0.22 (significant); medium shot = − 0.25 (significant)]. Thus, H4a and H4b are supported.

5 Discussion and conclusions

5.1 Theoretical implications

The analysis provides theoretical contributions to leisure constraint and narcissism literature, specifically related to vulnerable narcissism. First, although vulnerable narcissism exhibits certain overall tendencies at the aggregate level, this study offers evidence of the usefulness of viewing vulnerable narcissism through its various facets rather than at the aggregate level by showing that different vulnerable narcissism facets have different impacts.

Second, this study illustrates that vulnerable narcissism facets’ impact on attraction visit interest (H2) upon viewing different photograph types (full shot and medium shot) are mostly evident in wenqing attractions and restricted to entitlement rage and devaluing facets (H4). Devaluing positively influences wenqing attraction visit interest only for medium shot. While entitlement rage positively influences wenqing attraction visit interest for full shot, interestingly, its influence is negative for medium shot.

Wenqing attractions, being fashionable and crowd-drawing, are safe bets for tourists who are high in entitlement rage. This is evident in full shots where the attraction forms a major feature of the photograph. Although the visitor occupies a lesser part of the photograph, the photograph serves the prosaic purpose (Crawshaw and Urry 1997) of providing others with evidence of the visit and for others to see the visitor favorably because the photo is of the popular wenqing attraction. However, such a purpose increasingly diminishes as one moves to medium shots, as viewers will gradually have difficulty identifying the attraction in the photograph because the visitor becomes a major part of the photograph, sometimes at the expense of the attraction. Hence, viewers’ worry that others might not be interested in them starts to kick in, resulting in entitlement rage lowering wenqing attraction visit interests.

However, viewers with high devaluing see medium-shot photographs differently, with devaluing positively influencing wenqing attraction interest only for medium-shot photographs. Unlike entitlement rage, in which not meeting expectations is met by anger, tourists high in devaluing react through avoidance (Naidu et al. 2019). Tourists high in devaluing (Naidu et al. 2019) will find following the crowd useful since these attractions will receive approving responses from others and help profile the tourists. By associating themselves with the wenqing attractions yet also highly visible in the photographs (especially through medium shots), it will result in others having a strong sense of their presence—thereby lowering the nasty outcome of others not knowing them.

Third, this study shows how lack of interest constraint at destination level affects attraction visit interest (H3). For both photograph types, the constraint only lowers natural and monument attraction visit interest, thus showing that the same constraint perceived at destination level has different impacts on various attractions, despite them being within the same destination. Thus, it is too simplistic to project the negative impact of travel constraints at destination level to the attraction level. For example, while lack of interest constraint at the destination level lowers visit interest to natural attractions and monument attractions, the negative consequence is absent in wenqing attractions, reflecting that wenqing attractions (being fashionable and the “darling” of the day) are immune to the constraint’s negative effect.

Fourth, this study provides insight into vulnerable narcissism’s influence on travel constraints (H1). As postulated, entitlement rage positively influences lack of interest constraint. Entitlement rage involves one getting angry with others (Naidu et al. 2019). Thus, the best excuse for avoiding tourist destination is lack of interest constraint, which involves oneself only. This study is a first step in examining the relationship between vulnerable narcissism and travel constraints. Further studies are suggested.

5.2 Practical implications

This study offers practical implications. Wenqing attractions are the only attraction type not negatively affected by lack of interest constraint. Such attractions are able to draw tourists and social media discussions because they are often new, fashionable, and “must-see” attractions. Given their success, destination marketing organizations (DMOs) and wenqing operators have to ensure that wenqing attractions are constantly created or reinvigorated to remain relevant since these are also fast-moving fads. Given that entitlement rage and devaluing facets’ influence on wenqing attraction visit interest is affected by photograph type, wenqing attraction operators can provide optimal photography locations for tourists to take photographs that are “Instagrammable” (Taylor 2020)—particularly iconic backdrops that make the key attraction attributes prominent and easily and clearly identifiable by photograph viewers, even for medium-shot photographs. Such a move can help the operators maintain or increase online discussion and sustain the hype. This approach also allows entitlement rage and devaluing to positively influence wenqing attraction visit interest when viewers view full shots and medium shots, respectively, and lower entitlement rage’s negative impact on wenqing attraction visit interest for medium shots. Although visitor-captured photographs provide a condensed version of the destination image, visitors may not align the image with that of DMOs. To have more control, DMOs can incorporate suitable medium-shot photographs that have iconic elements of the wenqing attraction as backdrop in their social media or website to trigger viewers’ visit interest and serve as a template for others to imitate. Since tourists often want to photograph the attraction as they had previously seen in other materials (Kim and Stepchenkova 2015), it will set off the hermeneutic circle wherein place myths are reinforced by tourists sharing photographs taken at famous sites (Pearce and Moscardo 2015; Urry and Larsen 2011). This approach can also minimize the negative impact of entitlement rage and maximize the positive impact of devaluing on wenqing attraction visit interest. This suggestion is in line with suggestion that DMOs should include photographs taken by tourists in their promotion campaign (Deng and Li 2018; Rosa et al. 2019). There are also practical implications for Hualien DMO. Hualien DMO needs to continually pay attention to its natural attractions because tourists often see Hualien as a nature-based destination. Since wenqing attractions are the only attraction type not negatively affected by the lack of interest constraint, Hualien DMO should also continue to work with the private sector to develop and have more wenqing attractions to diversify its sources of attractiveness although natural attractions are a good match with Hualien.

5.3 Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations that provide directions for future research. This study adopted convenience sampling method, which limited its generalizability. This study only considered lack of interest constraint. Future studies should extend the study to consider how narcissism personality trait affects other types of travel constraints. This study has examined vulnerable narcissism. Future studies could also include and consider grandiose narcissism and its three facets (grandiose fantasy, self-sacrificing self-enhancement, and exploitativeness) (Naidu et al. 2019). For a sharper focus, this study considered Hualien, a nature-based destination, and its attractions. Future studies can consider other types of destinations other than nature-based destinations. Close-up shots are photographs that place greater emphasize on the human subject than medium shots. Studies which involve close-up shots could also be conducted. Future studies could consider how the characteristics of the visitors appearing in the photographs (such as age, gender, and attractiveness) affect how viewers view these photographs. Furthermore, future research could include the use of eye tracking (Casado-Aranda et al. 2023) for linking the time spent/areas viewed with different types of photographs (full shot, medium shot, and close-up shot) and associated them with the extent of vulnerable narcissism and attraction visit intention of the viewers.

References

Alexandris K, Tsorbatzoudis C (2002) Perceived constraints on recreational sport participation: investigating their relationship with intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation and amotivation. J Leis Res 34(3):233–252

Alexandris K, Funk DC, Pritchard M (2011) The impact of constraints on motivation, activity attachment, and skier intentions to continue. J Leis Res 43:56–79

Alexandris K, Karagiorgos T, Ntovoli A, Zourladani S (2022) Using the theories of planned behaviour and leisure constraints to study fitness club members’ behavior after Covid-19 lockdown. Leis Stud 41(2):247–262

Armutcu B, Tan A, Amponsah M, Parida S, Ramkissoon H (2023) Tourist behaviour: the role of digital marketing and social media. Acta Psychol 240:104025

Balcerowska JM, Sawicki AJ (2022) Which aspects of narcissism are related to social networking sites addiction? The role of self-enhancement and self-protection. Pers Individ Differ 190:111530

Barnett MD, Haygood AN, Mollenkopf KK (2023) Intrinsic and extrinsic emotion regulation strategies in relation to pathological narcissism. Curr Psychol 42:3917–3923

Bassols-Gardella N, Coromina L (2022) The perceived image of multi-asset tourist destinations: investigating congruence across different content types. Serv Bus 16:57–75

Boothby J, Tungatt M, Townsend A (1981) Ceasing participation in sports activity: reported reasons and their implications. J Leis Res 13:1–14

Bukowski H, Samson D (2021) Automatic imitation is reduced in narcissists but only in egocentric perspective-takers. Acta Psychol 213:103235

Canavan B (2017) Narcissism normalisation: tourism influences and sustainability implications. J Sustain Tour 25(9):1322–1337

Casado-Aranda LA, Sánchez-Fernández J, Bigne E, Smidts A (2023) The application of neuromarketing tools in communication research: a comprehensive review of trends. Psychol Mark 40(9):1737–1756

Casale S, Fioravanti G, Rugai L (2016) Grandiose and vulnerable narcissists: who is at higher risk for social networking addiction? Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 19(8):510–515

Chen F, Dai S, Xu H, Abliz A (2021) Senior’s travel constraint, negotiation strategy and travel intention: examining the role of social support. Int J Tour Res 23(3):363–377

Chin WW (1998) The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In: Marcoulides GA (ed) Modern methods for business research. Lawrence Erlbaum, New York, pp 295–358

Christou P, Farmaki A, Saveriades A, Georgiou M (2020) Travel selfies on social networks, narcissism and the “attraction-shading effect.” J Hosp Tour Manag 43:289–293

Crawshaw C, Urry J (1997) Tourism and the photographic eye. In: Rojek C, Urry J (eds) Touring cultures: transformations of travel and theory. Routledge, London, pp 176–195

Davies A, Prentice R (1995) Conceptualizing the latent visitor to heritage attractions. Tour Manag 16:491–500

Day NJS, Townsend ML, Grenyer BFS (2020) Living with pathological narcissism: a qualitative study. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregulation 7:19

Deng N, Li X (2018) Feeling a destination through the “right” photos. Tour Manag 65:267–678

Deng N, Liu J (2021) Where did you take those photos? Tourists’ preference clustering based on facial and background recognition. J Dest Mark Manag 21:100632

Duffy A, March E, Jonason PK (2023) Intimate partner cyberstalking: exploring vulnerable narcissism, secondary psychopathy, borderline traits, and rejection sensitivity. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 26(3):147–152

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50

Fredman P, Heberlein TA (2005) Visits to the Swedish mountains: constraints and motivations. Scand J Hosp Tour 5:177–192

Godbey G, Crawford DW, Shen XS (2010) Assessing hierarchical leisure constraints theory after two decades. J Leis Res 42(1):111–134

Greitemeyer T (2022) The dark side of sports: personality, values, and athletic aggression. Acta Psychol 223:103500

Grezo M, Adamus M (2022) Light and dark core of personality and the adherence to COVID-19 containment measures: the roles of motivation and trust in government. Acta Psychol 223:103483

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL (2006) Multivariate data analysis. Pearson Publishers, Upper Saddle River

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sinkovics RR (2009) The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Adv Int Mark 20:277–320

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43(1):115–135

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2016) Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int Mark Rev 33(3):405–431

Hollebeek LD, Sprott DE, Urbonavicius S, Sigurdsson V, Clark MK, Riisalu R, Smith DLG (2022) Beyond the big five: the effect of Machiavellian, narcissistic, and psychopathic personality traits on stakeholder engagement. Psychol Mark 39(6):1230–1243

Hong JM, Lim RE, Atkinson L (2021) “Doing good” versus “being good”: the interplay between pride appeals and regulatory-focused messages in green advertising. J Appl Soc Psychol 51(11):1089–1108

Hubbard J, Mannell R (2001) Testing competing models of the leisure constraint negotiation process in a corporate employee recreations setting. Leis Sci 23:145–163

Jackson EL (2000) Will research on leisure constraints still be relevant in the twenty-first century? J Leis Res 32(1):62–68

Jasen K. (2018) These are the 4 essential camera shot types every photographer needs to know. https://www.lightstalking.com/camera-shot-types

Jauk E, Weigle E, Lehmann K, Benedek M, Neubauer AC (2017) The relationship between grandiose and vulnerable (hypersensitive) narcissism. Front Psychol 8:1600

Jian Y, Lin J, Zhou Z (2021) The role of travel constraints in shaping nostalgia, destination attachment and revisit intentions and the moderating effect of prevention regulatory focus. J Dest Mark Manag 19:100516

Jiang J, Zhang J, Zheng C, Zhang H, Zhang J (2020) Natural soundscapes in nature-based tourism: leisure participation and perceived constraints. Curr Issues Tour 23(4):485–499

Kim DH, Jang SCS (2019) The psychological and motivational aspects of restaurant experience sharing behavior on social networking sites. Serv Bus 13:25–49

Kim H, Stepchenkova S (2015) Effect of tourist photographs on attitudes towards destination: manifest and latent content. Tour Manag 49:29–41

Knollenberg W, Kline C, Jordan E, Boley BB (2020) Will US travelers be good guests to Cuba? Examining US traveler segments’ sustainable behavior and interest in visiting Cuba. J Dest Mark Manag 18:100505

Lebrun AM, Corbel R, Bouchet P (2022) Impacts of Covid-19 on travel intention for summer 2020: a trend in proximity tourism mediated by an attitude towards Covid-19. Serv Bus 16:469–501

Lee JA, Sung Y (2016) Hide-and-seek: narcissism and “selfie”-related behavior. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 19(5):347–351

Lustman M, Wiesenthal DL, Flett GL (2010) Narcissism and aggressive driving: is an inflated view of the self a road hazard? J Appl Soc Psychol 40(6):1423–1449

Naidu ES, Patock-Peckham JA, Ruof A, Bauman DC, Banovich P, Frohe T, Leeman RF (2019) Narcissism and devaluing others: an exploration of impaired control over drinking as a mediating mechanism of alcohol-related problems. Pers Individ Differ 139:39–45

Neave L, Tzemou E, Fastoso F (2020) Seeking attention versus seeking approval: how conspicuous consumption differs between grandiose and vulnerable narcissists. Psychol Mark 37:418–427

Nolasco-Cirugeda A, García-Mayor C, Lupu C, Bernabeu-Bautista A (2022) Scoping out urban areas of tourist interest though geolocated social media data: Bucharest as a case study. Inf Technol Tour 24:361–387

Park E, Kim S (2018) Are we doing enough for visual research in tourism? The past, present, and future of tourism studies using photographic images. Int J Tour Res 20:433–441

Pearce J, Moscardo G (2015) Social representations of tourist selfies: new challenges for sustainable tourism. In Conference Proceedings of BEST EN Think Tank XV. Skukuza, pp. 59–73

Pincus AL, Lukowitsky MR (2010) Pathological narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 6:421–446

Ren M, Vu HQ, Li G, Law R (2021) Large-scale comparative analyses of hotel photo content posted by managers and customers to review platforms based on deep learning: implications for hospitality marketers. J Hosp Mark Manag 30(1):96–119

Riera M, Iborra M (2023) Looking at the darker side of the mirror: the impact of CEO’s narcissism on corporate social irresponsibility. Eur J Manag Bus Econ. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJMBE-09-2022-0289

Robinson P (2014) Emediating the tourist gaze: memory, emotion and choreography of the digital photograph. Inf Technol Tour 14:177–196

Rosa A, Bocci E, Dryjanska L (2019) Social representations of the European capitals and destination e-branding via multi-channel web communication. J Dest Mark Manag 11:150–165

Schoenleber M, Roche MJ, Wetzel E, Pincus AL, Roberts BW (2015) Development of a brief version of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory. Psychol Assess 27(4):1520–1526

Sun T, Zhang J, Zhang B, Ong Y, Ito N (2022) How trust in a destination’s risk regulation navigates outbound travel constraints on revisit intention post-COVID-19: segmenting insights from experienced Chinese tourists to Japan. J Dest Mark Manag 25:100711

Sung Y, Lee JA, Kim E, Choi SM (2016) Why we post selfies: understanding motivations for posting pictures of oneself. Pers Individ Differ 97:260–265

Swarbrooke J (2002) The development and management of visitor attractions, 2nd edn. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford

Taecharungroj V, Mathayomchan B (2021) Traveller-generated destination image: analysing Flickr photos of 193 countries worldwide. Int J Tour Res 23:417–441

Tan WK, Kuo CY (2014) Prioritization of facilitation strategies of park and recreation agencies through DEMATEL analysis. Asia Pac J Tour Res 19(8):859–875

Tan WK, Lin CH (2021) Why do individuals word-of-mouth destinations they never visited? Serv Bus 15(1):131–149

Tan WK, Liou PH (2020) Analysis of the relationship between the perceived extent of a tourist destination and smartphone use. Serv Bus 14:263–285

Tan WK, Yang CY (2021) The relationship between narcissism and landmark check-in behaviour on social media. Curr Issues Tour 24(24):3489–3507

Taylor DG (2020) Putting the “self” in selfies: how narcissism, envy and self-promotion motivate sharing of travel photos through social media. J Travel Tour Mark 37(1):64–77

Thompson R, Bowen CJ (2009) Grammar of the shot, 2nd edn. Focal Press, Burlington

Tribe J, Mkono M (2017) Not such smart tourism? The concept of e-lienation. Ann Tour Res 66:105–115

Trpkovski A, Vu HQ, Li G, Wang H, Law R (2018) Automatic hotel photo quality assessment based on visual features. In: Stangl B, Pesonen J (eds) Information and communication technologies in tourism. Springer, Switzerland, pp 394–406

Turi A, Rebeles MR, Visu-Petra L (2022) The tangled webs they weave: a scoping review of deception detection and production in relation to dark triad traits. Acta Psychol 226:103574

Urry J, Larsen J (2011) The tourist gaze 3.0. Sage, London

Velotti P, Rogier G, Sarlo A (2020) Pathological narcissism and aggression: the mediating effect of difficulties in the regulation of negative emotions. Pers Individ Differ 155:109757

Vermeeren L, de Kloet J (2020) “We are not like the calligraphers of ancient times”: a study of young calligraphy practitioners in contemporary China. In: Frangville V, Gaffric G (eds) China’s youth cultures and collective spaces: creativity, sociality, identity and resistance. Routledge, Oxon

Weiss B, Miller JD (2018) Distinguishing between grandiose narcissism, vulnerable narcissism, and narcissistic personality disorder. In: Hermann AD, Brunell AB, Foster JD (eds) Handbook of trait narcissism: key advances, research methods, and controversies. Springer, Switzerland, pp 3–13

Yang ECL, Lai MY, Nimri R (2022) Do constraint negotiation and self-construal affect solo travel intention? The case of Australia. Int J Tour Res 24:347–361

Zhang H, Zhang J, Cheng S, Lu S, Shi C (2012) Role of constraints in Chinese calligraphic landscape experience: an extension of a leisure constraints model. Tour Manag 33(6):1398–1407

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, WK., Dong, JY. Narcissism on display? Effects of full-shot and medium-shot photographs posted on social media on tourists’ attraction visit interest. Serv Bus 18, 339–361 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-024-00564-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-024-00564-0