Abstract

Intrapreneurship is one of the keys to survival and competitiveness for service companies in knowledge-intensive sectors such as banking. This paper analyzes the role of high-performance work systems, knowledge management processes, and supervisor support in promoting intrapreneurial behavior. The results indicate that the relationship of high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior is positive and significant. However, this relationship is mediated by knowledge management processes. Supervisor support moderates the relationships between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior and between high-performance work systems and knowledge management processes. However, this moderating effect is contrary to the expected effect for the second of these relationships. These findings offer guidance for practitioners to promote intrapreneurship in service sectors, where human-related service innovations, which are central to intrapreneurship, strongly affect customer satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the present business context, renewal, constant innovation, and the search for new business opportunities are essential for business survival and success. These elements are especially important in knowledge-intensive service sectors such as finance (Brand et al. 2021; Zaefarian et al. 2017). Banks are becoming proactively engaged in sustainable activities. This engagement is part of their strategy to create value by improving their public image, which has been heavily damaged by the 2008 financial crisis (McDonald and Lai 2011). Igbudu et al. (2018) reported that the adoption of a sustainable banking approach can help banks develop a competitive advantage, especially those that seek bank loyalty. In this context, the transformation from a traditional bank to a sustainable bank requires the renewal and reinvention of banking processes and services. Transitioning banks must use a sustainable innovation model whose core principle is the need to create shared value across three dimensions: economic, social, and environmental. This transition to sustainability requires more than innovation on an ad hoc basis. Instead, banks must develop competencies for continuous innovation (Berzin et al. 2016).

In the case of service industries such as banking, human service is the factor that most affects the customer experience. In such industries, human-related service innovations, which are at the heart of intrapreneurship, affect customer satisfaction and customer delight more strongly than technology-related service innovations (Tai et al. 2021). Therefore, to achieve this essential transformation, banks must mobilize and develop organizational talent (Lin 2022). They must also promote intrapreneurial behaviors within the organization (Canet-Giner et al. 2022; Escribá-Carda et al. 2020). The reason is that innovation and entrepreneurship at the corporate level are supported and driven by the attitudes, behaviors, and initiatives of the individuals who together form the organization (Rigtering and Weitzel 2013). One especially important group of individuals consists of those who the literature refers to as knowledge workers (Druker 2002; Lepak and Snell 2002). They are the key employees of innovative firms (Hayton et al. 2013).

Intrapreneurial behavior is the set of “individual behaviours that occur when employees take the initiative to develop an anticipatory and innovative vision in the workplace and overcome obstacles to creating added value for the business that employs them” (Chouchane and St-Jean 2022, p. 3). Intrapreneurs act entrepreneurially within an organization, recognizing opportunities and innovating within a hierarchy (Blanka 2019; Carmelo-Ordaz et al. 2012; Razavi and Ab Aziz 2017). Individuals’ intrapreneurial behavior, or intrapreneurship, appears in the form of opportunity identification and exploitation by individual workers to enable the organization to advance. It is characterized by innovative, proactive, and risk-taking behaviors (De Jong et al. 2015).

Numerous authors have linked human resources (HR) practices or systems of practices to intrapreneurship and knowledge management. HR practices are applied every day within organizations and embody their human resource management (HRM) philosophy and policies. They reside within the framework of programs aimed at attracting, retaining, developing, and motivating talent, as well as fostering the roles the company needs to achieve its organizational aims. This study examines the role of HR practices as precursors of intrapreneurship behavior. The study considers this role directly as well as indirectly through the effects of HR practices on knowledge management processes from a systemic perspective. The concept of high-performance work systems (HPWS) is introduced to refer to a set of mutually beneficial HRM practices that exerts a synergic effect on employees’ attitudes and behavior.

The study focuses on employees’ perceptions of high-performance work systems rather than middle managers’ or HR managers’ assessments of intended high-performance work systems. This employee-centric approach was adopted because employees’ perceptions of practices are ultimately what affect employees’ attitudes and behaviors (Arthur and Boyles 2007; Liu et al. 2020; Ostroff and Bowen 2016). Agarwala (2003), Alfes et al. (2019), and Escribá-Carda et al. (2020) have already highlighted the need to study how individuals feel or perceive HRM practices and how their perceptions influence their attitudes and behaviors. Given this employee-centric approach, any mention of high-performance work systems in the text should be interpreted as referring to employees’ perceived high-performance work systems.

Studies have examined the relationship between isolated HR practices, bundles of practices or high-performance work systems, and intrapreneurship. Most concur with the idea that high-performance work systems can boost intrapreneurship (Dal Zotto and Gustaffson 2008; Farrukh et al. 2021; Hayton 2005; Madu and Urban 2014; Tang et al. 2015; Teneau and Dufour 2015; Waheed et al. 2018). However, several authors have noted that knowledge essentially depends on and resides in people and that, therefore, issues related to HRM are vital for knowledge management in companies (Currie et al. 2003; Edvardsson 2008; Evans 2003). The importance of HR practices lies in the fact that they can facilitate knowledge management processes such as knowledge acquisition, sharing, and interpretation (Cabrera and Cabrera 2005; Escribá-Carda et al. 2017; Malik et al. 2020; Minbaeva 2013; Oltra 2005).

Where knowledge management processes have been cited as an antecedent of intrapreneurship (Crossan and Berdrow 2003; Hayton 2005; Lin 2007; Liu and Lee 2015), they seem to play a mediating role in the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurship. Authors such as Escribá-Carda et al. (2017) and Mustafa et al. (2016) have adopted such a position. However, the number of studies that have addressed these relationships is still small. This scarcity of research is the reason for the choice of research focus in the present study.

Middle managers are also a key element in creating an intrapreneurial culture (Blanka 2019). Supervisor support for employees who offer new ideas and initiatives strengthens employee commitment to innovation. It makes employees more likely to take certain risks and be more proactive (Chouchane and St-Jean 2022). Scholars such as Revuelto-Taboada et al. (2019) and Rehman et al. (2019) have posited that supervisor support moderates the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior. However, evidence in this regard is still scarce, hence the need to address this issue in the current paper.

In short, as its title indicates, the aim of this study is to examine the role of high-performance work systems, knowledge management processes, and supervisor support in fostering intrapreneurial behavior. The study also explores the interactions between these elements. A particularly relevant focus of this study is its analysis of the relationships between high-performance work systems, knowledge management processes, and intrapreneurial behavior. Such analysis is important for several reasons. First, most studies have examined these two antecedents separately (Farrukh et al. 2021; Lin 2007). Second, little emphasis has been placed on studying the relationship between knowledge management processes and intrapreneurial behavior because the former has been linked more specifically to innovation or knowledge spillover effects on entrepreneurship (Audretsch et al. 2020; Palacios et al. 2009). Finally, in general, when knowledge management processes have been considered as a mediator of the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior, only the process of knowledge sharing has been considered (Escribá-Carda et al. 2020; Mustafa et al. 2016).

To achieve its aims, the paper is presented in four further sections. Following this introductory section, the second section develops the theoretical framework across three subsections on the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior, the role of knowledge management processes in this relationship, and the role of supervisor support in the relationships between high-performance work systems, knowledge management processes, and intrapreneurial behavior. The method is presented in the third section. A sample of 1885 qualified employees from three financial institutions is described, along with the measurement instruments and the analysis procedure of variance-based structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The fourth section describes the validation of the measurement model, which provided acceptable results. The structural model is then examined, with results that validate most of the hypotheses. Broadly, these results indicate that the relationship of high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior is positive and significant and that it is mediated by knowledge management processes. Supervisor support moderates the relationships between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior and between high-performance work systems and knowledge management processes. However, the nature of the relationship was contrary to what was expected in the second case. In the final section, the conclusions, limitations, and practical implications of the study are presented.

2 Theoretical framework and hypothesis development

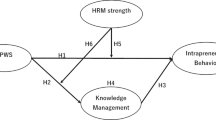

The hypotheses proposed in this section are summarized in Fig. 1.

2.1 High-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior

Although high-performance HR practices have been defined in numerous ways Lertxundi and Landeta (2011) highlighted a common theme to all these definitions. This common theme is the desire to improve organizational performance through organizational models and HR practices that nurture the skills, motivation, and commitment of the people in the organization. In the present study, high-performance practices are conceptualized in line with this definition as a set of mutually beneficial high-performance HR practices that exerts a synergic effect on employees’ attitudes and behavior.

Crucially, the attitudinal and behavioral consequences of high-performance HR practices depend on how employees perceive these practices (Arthur and Boyles 2007; Kehoe and Wright 2013; Liu et al. 2020; Mustafa 2016). Hence, it is vital to analyze individuals’ subjective perceptions of these practices (Alfes et al. 2019; Canet-Giner et al. 2020; Escribá-Carda et al. 2020; Piening et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2020). Three main theoretical frameworks are used to support the relationships in the model: social exchange theory, social identity theory, and the ability motivation opportunity framework (AMO model).

An organization’s investment in high-performance HR practices signals its intention to invest in skills, offer its workers opportunities, and develop mutually beneficial long-term relationships with employees (Chang and Chin 2018; Sun et al. 2007). As suggested by social exchange theory (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005; Rhoades and Eisenberger 2002; Sungu et al. 2019), employees who perceive their organizational environment as being supportive will feel obliged to reciprocate with behaviors that are beneficial to the organization. Social exchanges involve discretionary actions and extra-role behaviors (Rhoades and Eisenberger 2002; Tavares et al. 2016) such as intrapreneurial behavior.

From a social identity theory perspective, the psychological linkage between the individual and the organization is captured by the concept of organizational identification (Ashforth and Mael 1989). Being part of an organization that deploys high-performance work systems should make employees feel proud, strengthen their positive self-concept, and heighten their organizational identification (De Roeck et al. 2016). The results of Liu et al. (2020) and Newman et al. (2016) support the idea that perceived high-performance work systems may lead to organizational identification. Finally, the more people identify with their organization, the more likely they will be to act with the organization’s best interests in mind. Hence, they will be more likely to perform discretionary actions and extra-role behaviors (Riketta 2005; Tavares et al. 2016; Van Dick et al. 2006). Furthermore, Tavares et al. (2016) showed that social exchange theory and social identity theory can be combined. Their findings show that the level of organizational identification affects the content of the social exchange. That is, the range of an individual’s exchange currencies is adequate to reciprocate perceived organizational support. Higher organizational identification increases the probability of reciprocating organizational commitment with extra-role behaviors.

Finally, the AMO model suggests that acting on employees’ ability, motivation, and opportunity to perform specific tasks and roles is essential to ensure that employees “go the extra mile” (Appelbaum et al. 2000; Boxall 2003; Obeidat et al. 2016). Consequently, the implementation of high-performance work systems can prepare, motivate, and provide chances for employees to identify and exploit opportunities arising from changes in an increasingly shifting environment (Farrukh et al. 2021; Jiang et al. 2012).

Over the last decade, an abundance of studies have examined the relationship between perceptions of high-performance HR practices and their impact on corporate entrepreneurship (or intrapreneurship). Most studies of this relationship, whether at the organizational or individual level, have examined high-performance work systems rather than isolated practices. The present research follows this systemic approach because the specialized literature shows that the effects of high-performance HR practices are greater when these practices are defined as bundles that are applied in a synergistic way (Combs et al. 2006; Delery and Shaw 2001).

One stream of research consists of examining intrapreneurship at the organizational level (Messersmith and Wales 2013; Mustafa et al. 2016; Schmelter et al. 2010; Tang et al. 2015; Zhang and Jia 2010; Zhang et al. 2008; Yu 2013). These studies display a consensus in suggesting the existence of positive relationships between HR practice systems and corporate entrepreneurship. However, these studies ignore links in the causal chain connecting high-performance work systems with corporate entrepreneurship. They fail to consider the individual and group processes that mediate the relationship between the two constructs. The relationship between high-performance work systems and organizational performance dimensions (in this case, corporate entrepreneurship) is not direct. Managerial policies, practices, and decisions are made at the organizational level, but their effect on employees takes place at the individual level. Hence, individual decisions at the individual level will affect organizational performance through individual actions. However, sometimes, these individual actions are the result of collective processes at an intermediate ontological level such as teams or groups. Hence, the chain linking high-performance work systems and corporate entrepreneurship has many intermediate links that reveal the constant interactions between different ontological levels.

A second stream of research provides key references for the present study. This second stream of research focuses on the relationships between high-performance work systems and individual intrapreneurial behavior as a key behavioral antecedent of entrepreneurial performance, which provides the foundations for long-term business success (De Jong et al. 2015; Kraus et al. 2019; Neessen et al. 2019). Studies that have adopted a systemic approach to HRM (Canet-Giner et al. 2022; Escribá-Carda et al. 2020; Farrukh et al. 2021; Kühn et al. 2016) provide evidence of a significant positive relationship between high-performance work systems and the intrapreneurial behavior of employees. The arguments and evidence lead to the following hypothesis:

H1

There is a positive relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior.

2.2 The role of knowledge management processes in the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior

Knowledge ultimately resides in people, and effective knowledge management essentially depends on people. Consequently, HRM is vital for knowledge management in firms (Currie et al. 2003; Edvardsson 2008; Evans 2003). High-performance work systems demonstrate commitment to employees. Through this commitment, they are likely to lead to strong networks within the firm that support collaboration and knowledge exchange (Messersmith 2008). High-performance work systems help select, train, and motivate skilled employees, while fostering teamwork and autonomy. Among other effects, this situation increases the likelihood that employees share knowledge (Cabrera and Cabrera 2005; Lin and Lee 2005; Mustafa et al. 2016). According to the behavioral approach of HRM, high-performance work systems can also lead employees to interact actively and share knowledge for greater innovation (Hirst et al. 2009).

Most studies of the relationship between high-performance HR practices and knowledge management have focused exclusively on knowledge sharing processes (Camelo-Ordaz et al. 2011; Scarbrough 2003; Wang and Noe 2010). However, high-performance HR practices can enable different knowledge management processes such as knowledge acquisition and knowledge interpretation in addition to knowledge sharing (Cabrera and Cabrera 2005; Escribá-Carda et al. 2017; Malik et al. 2020; Minbaeva 2013; Oltra 2005). Training and development practices, job enrichment, and feedback from performance appraisals can undeniably play a role in improving knowledge acquisition and interpretation, just as the promotion of autonomy and teamwork, among other factors, can encourage knowledge sharing. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2

There is a positive relationship between high-performance work systems and knowledge management processes.

As noted by Audretsch et al. (2020), investment in knowledge within organizations allows them to accumulate human capital and achieve the critical mass of ideas needed to support entrepreneurial initiatives (Farrukh et al. 2021). Along these lines, Liu and Lee (2015) reported that effective knowledge management enables accumulation of the knowledge needed to enhance predictions of changes in the environment. It also leads to better anticipation of future business trends and better evaluation of strategic alternatives. It thus improves a company’s ability to use its resources by exploiting new opportunities (Wiklund and Shepherd 2003). As noted by Canet-Giner et al. (2020) and Jahanshahi et al. (2018), high-performance work systems can enhance and activate the stock of knowledge needed to discover and exploit new business opportunities and generate products, services, processes, marketing, and organizational innovations (OECD 2005). This idea suggests that knowledge management processes should be considered important for boosting intrapreneurial behavior.

Intrapreneurial behavior involves generating or adapting new solutions to problems, taking risks, persuading others to adopt new approaches, striving to pursue new opportunities, and implementing organizational changes. For this purpose, it is essential to explore, experiment, and be flexible to seek alternative viewpoints and perspectives in an active manner. Therefore, intrapreneurial behavior varies depending on the extent to which knowledge management processes are encouraged within the company (Revuelto-Taboada et al. 2019). In short, organizational learning and knowledge management processes are widely cited as being at the heart of intrapreneurship (Crossan and Berdrow 2003; Del Giudice and Della Peruta 2016; Hayton 2005; Lin 2007). Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3

There is a positive relationship between knowledge management processes and intrapreneurial behavior.

The relationships captured in Hypotheses 2 and 3 suggest mediation by knowledge management processes in the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior. In this regard, the scant literature on the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior (Mustafa et al. 2016; Ma et al. 2017; Dal Zotto and Gustaffson 2008) suggests that knowledge management processes play a key role. Several authors have reported that HR practices can enable the acquisition and integration of knowledge, which activates the stock of knowledge needed for the identification and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities in the firm (Escribá-Carda et al. 2017; Farrukh et al. 2021; Hayton 2005; Kuratko et al. 2005).

For instance, Mustafa et al. (2016) reported the mediating role of knowledge sharing in fostering corporate entrepreneurship. Escribá-Carda et al. (2017) validated the role of exploratory learning in the relationship between high-performance work systems and innovative behavior (a core dimension of intrapreneurial behavior). Escribá-Carda et al. (2020) showed the existence of mediation by knowledge sharing in the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior. Based on the limited evidence and these arguments, the following hypothesis can be proposed:

H4

Knowledge management processes partially mediate the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior.

2.3 The role of supervisor support in the relationships between high-performance work systems, knowledge management processes, and intrapreneurial behavior

Middle managers have a considerable influence on their subordinates because of the legitimacy of their authority and potential control over resources and relevant outcomes for employees such as performance, appraisals, and salaries (Chae et al. 2019). Supervisor support can limit the expression of individual differences and lead to standardized behaviors across employees (Meyer et al. 2010). The moderating effect of supervisor support on the relationships between knowledge management processes and their antecedents has received little attention from scholars. However, there are some arguments and examples of evidence in this regard.

Revuelto-Taboada et al. (2019) proposed a model that posited a possible moderating effect of employees’ perceived supervisor support on the relationship between high-performance work systems and knowledge management processes. Among the limited evidence, Kamdar and Van Dyne (2007), for example, reported that high supervisor support may reduce differences in knowledge‐sharing behavior across employees, even when they have different levels of dutifulness and achievement striving. El-Said et al. (2020) analyzed the process of transferring training to practice, which is directly related to what is referred to in this paper as knowledge management processes. They showed that supervisor support (in their study, specifically related to training) moderates the relationship between the opportunity to perform and the transfer of training, as well as the relationship between motivation to transfer and transfer of training.

Regarding the role of supervisor support in the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior, supervisors are a key element in creating an intrapreneurial culture. Their leadership style and type of relationship with subordinates play a key role in developing and supporting employees’ entrepreneurial behaviors (Blanka 2019). Supervisor support encourages employees to feel more confident in themselves and in their capabilities, helping them act more independently and impactfully, while empowering them (Spreitzer 1996; Rehman et al. 2019).

Supervisors who support employees who devise new ideas and initiatives strengthen their commitment to innovation. Such supervisors also reduce employees’ perceptions of risk and anxiety associated with the process, while making employees more likely to take certain risks and be more proactive (Chouchane and St-Jean, 2022). Conversely, a lack of managerial support for employees or bad error management inhibits the willingness and ability of employees to use their skills and knowledge at work (Janssen 2005; Jung and Yoon 2017). These arguments lead to the prediction that supervisor support plays a moderating role in both the direct relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior and the indirect relationship via knowledge management processes.

H5

Perceived supervisor support moderates the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior.

H6

Perceived supervisor support moderates the relationship between high-performance work systems and knowledge management processes.

3 Method

3.1 Sample and data collection

The data for the present study were collected in late 2018 and early 2019 using convenience sampling. The target population was skilled workers (knowledge workers) from three banking institutions in Ecuador. Banks with an existing relationship with the university system were invited to participate in the study. Three banks agreed to participate. Their employees provided the sample for the study. This sector was chosen because it is a knowledge-intensive sector where innovation and continual renewal are imperative. This process of innovation and renewal in this sector has been especially important since the 2008 crisis, where major shortcomings in both management and social responsibility in the banking sector were laid bare. Another key factor was the idea that employees are one of the most (if not the most) important factors in ensuring satisfied and loyal customers.

The data were collected more than 4 years prior to the study. However, they were still useful for analysis of the proposed relationships given that they referred to a period of relative stability before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The data corresponded to a dynamic sector that have recently been under pressure to engage in constant innovation and renewal. The subsequent period (2020–2022) would also have been of interest and has its own specific challenges for researchers. However, using data from the period 2020 to 2022 in a study of this type could substantially influence the relationships under study given the exceptional circumstances surrounding the COVID-19 crisis and the attendant measures.

The final version of the questionnaire was developed using the QuestionPro application. The questionnaire was sent by email in coordination with the HR manager of each bank. This same questionnaire was previously used to collect data from a sample of Spanish companies. It was adapted and translated from English to Spanish and then from Spanish to English with the help of an experienced translator. Likewise, a pilot test was conducted with eight employees who did not participate in the main study in Spain to verify that the items were correctly understood and to assess the ability of the chosen scales to capture the desired information. On the basis of the feedback, certain specific items were modified. Before administering the questionnaire to the employees of the three Ecuadorian banks that provided the sample for this study, the questionnaire text was reviewed once again by two native Ecuadorian scholars to adapt it to the conventions of Spanish language usage in Ecuador. The pretest was not repeated in Ecuador. Instead, a focus group was held with the bank representatives responsible for the process to clarify and contextualize the items.

The banks had 4776 non-executive (i.e., front-line) employees. The questionnaire was sent to employees belonging to specific departments linked to innovation, namely marketing, projects, planning, finance, HR, innovation, information technology, and auditing. In total, 1885 valid responses were received, corresponding to a response rate of approximately 39.5%. However, the HR managers decided which business units met the requirements to participate in the study and which employees could be defined as knowledge workers because of their prominent role in intrapreneurial initiatives and because knowledge management was a core part of their daily tasks. The research team sent the employees a link to the questionnaire, along with a brief description of the aims of the study and instructions on how to respond. The employees also received assurance that their responses would be treated confidentially. In total, 3350 questionnaires (vs. 4776 total employees) were sent, so the real response rate was 56.27%.

Regarding possible sample bias, Table 1 compares the employees in the sample with all employees who received the questionnaire in the participating banks. No major differences were observed, although the mean age for the population was slightly higher than the mean age for the sample.

3.2 Measurement instruments

All scales employed in this research had previously been used and validated in earlier studies, some of which are cited. Employee perceptions of the high-performance work systems that had been implemented were measured using the 15-item scale developed by Jensen et al. (2013) and validated by Escribá-Carda et al. (2020) for Spain. Seven items (training and development, selection, teamwork, status, job security, information sharing, and participation) were taken from the perceived HR practices scale originally developed by Gould-Williams and Davies (2005). The remaining eight items on development, motivation, communication, and empowerment were developed by Truss (1999). Example items include, “The appraisal system provides me with an accurate assessment of my strengths and weaknesses” and “I am provided with sufficient opportunities for training and development.” The variable knowledge management processes was measured using a 12-item scale. The scale, which was developed by Flores et al. (2012), had four items for each subprocess. Example items include, “We have processes to acquire relevant information from outside our company” for acquisition of information, “Lessons learned by one group are actively shared by others” for distribution of information, and “I do not hesitate to question things I do not understand” for interpretation of information. Supervisor support was measured using the four-item scale of Kuvaas and Dysvik (2010), adapted by Eisenberger et al. (1986). Example items include, “My supervisor cares about my opinions” and “My supervisor strongly considers my goals and values.”

The dependent variable, intrapreneurial behavior, was measured using a 12-item scale similar to that used by De Jong et al. (2011, 2015). The scale consisted of six items for innovative behavior from the scale designed by Scott and Bruce (1994), three items for risk-taking (two of them from Parker and Collins 2010), and three items for proactiveness (Zhao et al. 2005). Since the employees gave self-assessments of their intrapreneurial behavior, the items were adapted accordingly. Example items include, “I search out new technologies, processes, techniques, and/or product ideas” for innovative behavior, “I first act and then ask for approval, even if I know that I would annoy other people” for risk-taking, and “I put effort into pursuing new business opportunities” for proactiveness.

Age, gender, and educational level were included as control variables because they are the most commonly used control variables in the literature on entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship. In general, the results show that men have a more positive attitude toward entrepreneurship, whereas women appear to be less involved in intrapreneurship (Adachi and Hisada 2017; Parker 2011; Strobl et al. 2012). Previous research also indicates that older employees are less involved in intrapreneurship (Ben Hador and Klein 2020; Camelo-Ordaz et al. 2012; Urbano et al. 2013). The relationship between educational level and entrepreneurial behavior has also been extensively studied in the literature. Despite suggestions of a positive relationship, the results in the literature are ambiguous (Dickson et al. 2008; Van der Sluis et al. 2005). Gender was measured as a dichotomous variable (0 = woman; 1 = man). Age was measured as a categorical variable with the following categories: 1 = 18 to 30 years, 2 = 31 to 45 years, and 3 = 46 years or more. Education level was measured as a dichotomous variable (0 = secondary school or lower: 1 = university degree or higher).

3.3 Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using the variance-based technique of structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The analyses were performed using Smart PLS 3.3 software (Ringle et al. 2015). This method enables the estimation of complex models with multiple variables. It is aimed at the exploration of new relationships between variables from hypothesis-based models supported by strong theoretical foundations. It also allows for exploration of simultaneous indirect effects (Henseler et al. 2015). PLS-SEM models are essentially composed of two elements: a measurement model and a structural model. The measurement model evaluates the relationships between indicators and their constructs (validity and reliability). The structural model evaluates the predictive capacity of the relationships.

The results of the PLS-SEM were evaluated for these two elements. For the measurement model, reliability was estimated using the coefficients of rho_A and composite reliability. Convergent validity was estimated using outer loadings and the average variance extracted (AVE). Finally, discriminant validity was estimated using the Fornell-Larker (1981) criterion. The evaluation of the structural model was based on the explained variance, effect size, predictive effect, and magnitude and statistical significance of the coefficients for each path proposed in the conceptual model.

Before analyzing the SEM model, tests were performed to check for problems associated with common method bias. Such problems can occur when estimates of the relationships between two or more constructs are biased because they have been measured using the same method (Podsakoff and Organ 1986). Following the recommendations of Kock and Lynn (2012), a new model was created where all latent variables referred to a new random variable (a single-indicator latent variable). Next, PLS was run to check whether the inner model variance inflation factors (VIFs) were less than 3.3 (Kock 2015). Only one item (INTINFO02: “I seek to deeply understand issues and concepts”) had a value that exceeded this threshold. Hence, there was no evidence to suggest a major problem with common method variance.

4 Results

4.1 Assessment of the measurement model

Reliability was assessed by analyzing internal consistency. The four variables analyzed in this research had adequate levels of reliability. Both the rho_A coefficient and the composite reliability were greater than 0.65. These results implied that the constructs were reliable, based on the criteria provided in the specialized literature (see Table 2).

Convergent validity assesses whether the items of a construct truly measure the same concept and are thus highly correlated. This evaluation criterion was applied at the construct level and the observed indicator level. Average variance extracted (AVE) was used as an estimator for the constructs. Values above 0.50 imply that the construct shares more than half of its variance with its indicators and implies an acceptable level of validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981). At the observed indicator level, two criteria were used. With outer loadings, values greater than 0.707 are considered acceptable. With the variance inflation factor (VIF), possible collinearity effects were evaluated, given that values of less than 5.0 are considered acceptable in the social sciences for early stage models (Fornell and Larcker 1981).

During the analysis, two items were removed from the high-performance work systems scale: MI1 (“There is a clear difference in status between managers and employees in this department”) and ST1 (“I feel like my job is permanent”). Two items were removed from the knowledge management processes scale: AI2 (“We constantly benchmark ourselves against our competitors”) and II3 (“I do not hesitate to question things I do not understand”). Finally, three items were removed from the intrapreneurial behavior scale: Risk1 (“As an employee, I take risks at work”), Risk2 (“As an employee, when the stakes are high, I try to win big, even when things go completely wrong”), and Risk3 (“I act first and then ask for approval, even if I know it will upset others”).

Discriminant validity seeks to determine the extent to which a construct differs from the other constructs in the model. The most widely accepted criterion is that the square root of the AVE should be greater than the correlation between constructs (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Results are provided in Table 3. In general, the criterion was met. However, in some cases, the values were almost equal.

4.2 Assessment of the structural model

The results for the structural model appear in Table 4. The total effect of high-performance work systems on intrapreneurial behavior was positive and statistically significant (β = 0.0551, t = 20.517, p = < 0.001). The effect size was measured using the criteria of Cohen (2013), according to which a value of ƒ2 > 0.02 is small, a value of ƒ2 > 0.15 is medium, and a value of ƒ2 > 0.35 is large. In this study, the effect of high-performance work systems on intrapreneurial behavior was small (ƒ2 = 0.004). These results provided partial empirical support for Hypothesis 1, with the caveat that the effect size was small. The effect of high-performance work systems on knowledge management processes was positive and statistically significant (β = 0.0675, t = 32.020, p < 0.001). The effect size was large (ƒ2 = 0.702). The results provided strong empirical support for Hypothesis 2.

The mediating role of knowledge management processes in the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior was captured by Hypotheses 3 and 4. The results showed that, after including the construct for knowledge management processes, the impact of high-performance work systems on intrapreneurial behavior was negative and significant, contrary to what was expected. However, in this case, the result only held for a value of α of 0.05 (β = − 0.070, t = 2.291, p = 0.0022). The indirect effect of high-performance work systems on intrapreneurial behavior was positive and significant (β = 0.621, t = 23.988, p = 0.000). Therefore, it was concluded that the knowledge management processes construct partially mediated the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior. In other words, Hypothesis 3, which proposed a positive relationship between knowledge management processes and intrapreneurial behavior was validated, as was Hypothesis 4, which proposed mediation by knowledge management processes.

The possible moderating effect of supervisor support on the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior and on the relationship between high-performance work systems and knowledge management processes was proposed in Hypotheses 5 and 6. To test for this effect, the product indicator method was used. This method used all possible combinations of the observed variables for both the latent predictor construct and the moderator to calculate the interaction effect proposed in the structural model (Fig. 2).

In the case of the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior, the results showed a small significant moderating effect of supervisor support for a value of α of 0.05 (β = 0.034, t = 2.031, p = 0.043). These results supported Hypothesis 5. Regarding the relationship between high-performance work systems and knowledge management processes, the results showed a significant moderating effect of supervisor support. However, the sign was the opposite of what was expected (β = − 0.070, t = 3.603, p < 0.001). These results did not agree with what was predicted in Hypothesis 6 (see Table 4).

Three control variables (gender, age, and education level) were also included in the evaluation of the structural model to test for possible effects on the endogenous variable of the model. As Table 5 shows, there was no significant relationship between age and intrapreneurial behavior. However, there was a weak significant relationship between gender and intrapreneurial behavior (β = 0.042, t = 3.329, p = < 0.001), and a weak significant relationship between educational level and intrapreneurial behavior (β = 0.054, t = 4.513, p = < 0.000). These results seemed to indicate that men were more entrepreneurial than women.

The predictive effect analysis (Q2 predict) was performed for the antecedent construct in the conceptual model. According to Hair et al. (2019), values of 0.01, 0.25, and 0.50 indicate low, medium, and high predictive relevance of the estimated path, respectively. The results implied that the high-performance work systems construct was of medium–high relevance as a predictor of intrapreneurial behavior (Q2 = 0.462) and knowledge management processes (Q2 = 0.410).

Finally, the analyses were repeated for each bank. No relevant differences were observed in these analyses. All hypotheses except H5 (HPWS * SS → IPB) were verified in each of the models. Regarding the moderating effect of supervisor support in the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior, differences were observed. This relationship became non-significant (p value = 0.0457; 0.079 and 0.066), most notably in the case of the first bank.

5 Discussion and conclusions

This study examined high-performance work systems as an antecedent of intrapreneurial behavior of knowledge workers in three financial institutions from the developing country of Ecuador. The analysis examined both direct effects and indirect effects through knowledge management processes, which acted as a mediator in the proposed model of analysis. The possible moderating role of supervisor support in these relationships was also examined. The analysis of these constructs and their relationships was performed using PLS-SEM.

The results confirm the existence of a positive relationship between employees’ perceptions of the high-performance work systems in their firm and their intrapreneurial behavior. The total effect of this relationship is positive. However, there is strong partial mediation by knowledge management processes. The effect of knowledge management processes reveals that the positive relationship between high-performance work system and intrapreneurial behavior derives from the influence of this mediator. These results are consistent with those reported by Portalanza-Chavarría and Revuelto-Taboada (2023). In other words, high-performance work systems are positively related to knowledge management processes, which in turn exert a positive influence on intrapreneurial behavior. Moreover, once knowledge management processes are considered, the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior becomes weak, less significant, and negative, contrary to what was expected. In short, it can be concluded that the positive influence of high-performance work systems on intrapreneurial behavior is indirect and occurs through knowledge management processes.

The results are generally consistent with those reported in previous studies. Schmelter et al. (2010) and Kühn et al. (2016) used multiple case studies to identify the high-performance HR practices that foster corporate entrepreneurship at the organizational and individual levels. They analyzed knowledge-intensive firms and professional service firms, respectively. Farrukh et al. (2021) confirmed a positive relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior, partially mediated by perceived organizational support.

Regarding the role of knowledge management processes, previous studies have almost exclusively examined the role of knowledge sharing processes. For example, Escribá-Carda et al. (2020) and Canet-Giner et al. (2022) showed that knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior in knowledge-intensive firms in Spain. Mustafa et al. (2016) confirmed that knowledge sharing mediates the relationship between HR practices and firm-level corporate entrepreneurship.

Second, the results also validate moderation by supervisor support in the relationships between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior and between high-performance work systems and knowledge management processes. In the case of the first of these relationships, supervisor support plays a moderating role as expected: the greater the supervisor support, the greater the effect of high-performance work systems on intrapreneurial behavior. Nevertheless, it is worth recalling that the positive and significant effect of high-performance work systems on intrapreneurial behavior occurs indirectly through knowledge management processes. Studies of these relationships are rare. There is no consensus regarding the role of supervisor support. Some scholars have reported direct effects on intrapreneurial behavior or some of its dimensions (Chouchane and St-Jean 2022). In contrast, others have reported findings that are more aligned with those of the present study, describing a moderating role (Rehman et al. 2019). Given this situation in the literature, further analysis of these relationships is necessary.

Contrary to what was expected, in the relationship between high-performance work systems and knowledge management processes, the results indicate that the effects of high-performance work systems on knowledge management processes become slightly smaller as supervisor support increases. The interpretation of these results is difficult given the scarcity of precedents in the literature with which to compare the present findings. Nevertheless, this surprising finding may have a plausible explanation in the context of the present study. According to the Hosfstede (2022) model of six cultural dimensions, in Ecuadorian culture, power distance is significantly higher than in more developed countries like Spain. There is an even greater difference with countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States, where much of the existing research has been performed. Hence, too much attention from supervisors may be interpreted as a strict control mechanism rather than an attempt to encourage proactive behavior and risk-taking. In other words, it could have a negative effect by stifling informal knowledge management process mechanisms. Finally, in the analysis of the three banks separately, this relationship was no longer observed to be significant, especially in the case of the first bank. Also, in the joint model, the level of significance of this hypothesis was the weakest (p < 0.05). Together, these results seem to indicate the need for further study of this relationship, which cannot yet be validated.

5.1 Theoretical implications

One of the most notable theoretical contributions of this paper is its attempt to fill a gap in the literature by addressing the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior under mediation by knowledge management processes. The relationship between high-performance work systems and knowledge management processes has been studied on numerous occasions (Edvardsson 2008; Malik et al. 2020). As noted earlier, previous research has generally considered these two antecedents of intrapreneurship separately (Farrukh et al. 2021; Lin 2007), and the findings reported in the literature are consistent with hypotheses H1 and H3. As already discussed, there has been less emphasis on the study of the relationship between knowledge management and intrapreneurship. The former has been more specifically linked to innovation, which is still an essential component of intrapreneurship, or knowledge spillover effects on entrepreneurship (Audretsch et al. 2020; Palacios et al. 2009). There are notable exceptions in which knowledge management has been considered as a mediator of the relationship between high-performance work systems and intrapreneurial behavior. However, in general, only the process of knowledge sharing has been considered (Escribá-Carda et al. 2020; Mustafa et al. 2016), whereas information acquisition and interpretation have been ignored. The present study validates this mediation hypothesis, considering the set of knowledge management processes (H4), after showing the existence of a direct positive relationship between high-performance work systems and knowledge management processes (H2).

Therefore, the study provides evidence that the positive influence of high-performance work systems on intrapreneurial behavior occurs through an improvement in knowledge management processes. This evidence is relevant from a theoretical point of view. It helps explain how a service company’s capacity for renewal and innovation can be improved by an internally consistent set of HR practices thanks to beneficial effects on how knowledge is acquired, transferred, and interpreted within the company. However, further analysis of the relationship is needed to outline what Jackson et al. (2014) defined as strategically targeted HRM systems, which (in this case) have the specific objective of improving knowledge management processes to drive intrapreneurial behavior.

Another relevant contribution relates to the role of supervisor support. It is usually reported in the literature as a moderator, enhancing relationships between high-performance work systems and a range of outcomes (Cai et al. 2019; Rehman et al. 2019). The validation of hypothesis H5 reinforces the idea that when supervisor support is greater, so too are the effects of high-performance work systems on behavioral outcomes. However, the present study suggests that the moderating effect of supervisor support on the relationship between high-performance work systems and knowledge management processes (H6) is contrary to what was expected. Specifically, high levels of supervisor support can reduce the impact of high-performance work systems on knowledge management processes. Cultural differences, particularly in terms of power distance, could explain this result. In fact, numerous studies have already highlighted the need to consider contextual factors such as culture when analyzing relationships such as those addressed by this research (Cooke et al. 2021; Rabl et al. 2014).

5.2 Managerial implications

A series of practical implications can be derived from this study. These implications are mainly aimed at managers and those responsible for HR. However, they are also relevant for middle managers, given their role in the processes addressed in this paper. Achieving effective intrapreneurship performance requires not only a suitable high-performance work system but also appropriate implementation of the system by middle managers. These middle managers are also responsible for creating an intrapreneurial culture in their business units, fostering relationships that allow subordinates to exploit their talent by encouraging independence and reducing the anxiety potentially associated with innovative processes. This situation requires an empowering leadership style whereby leaders must show faith in their subordinates, accepting their influence, encouraging their personal and professional development, and acting as resource providers.

In service companies, the human factor and knowledge are crucial for success. To improve knowledge management and intrapreneurship in these companies, HR practices should be defined. Doing so can enable companies to (a) recruit, select, and hire employees with suitable competencies; (b) invest in training and development, emphasizing specific knowledge and creative techniques; (c) foster a culture of teamwork and knowledge sharing that also encourages risk-taking; (d) involve everyone in innovation; (e) encourage versatility and autonomy through stable work relations; and (f) implement appraisal and reward systems that value and reward information sharing and intrapreneurial behaviors through both recognition and career progression.

In addition, given the importance of knowledge management processes in enhancing intrapreneurial behavior, companies are advised to explore the possibility of creating formal processes for knowledge exchange between individuals and departments by, for example, creating communities of practice. Likewise, exploratory learning from and through error should be encouraged. Accordingly, resource stocks are needed to overcome possible failures.

Finally, the gender-related differences in intrapreneurial behavior found in this study often require specific actions. Such actions are especially important in relation to eliminating the glass ceiling and gender biases. These situations limit women’s progress, reduce their ability to make the most of their talent, and undermine their self-confidence and, consequently, their perceived entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Policies are needed to ensure equal opportunities regardless of gender, empower women, and build a more inclusive workplace in service firms (AlEssa and Durugbo 2022).

5.3 Limitations and future research directions

Regarding the limitations of the study, problems can arise when using a self-report questionnaire and a single data source, which increases the likelihood of common method variance artificially inflating the relationships between variables (Podsakoff and Organ 1986; Podsakoff et al. 2003). However, certain steps were taken in this regard. First, respondents were qualified employees in knowledge-intensive areas and functions who had the potential to propose innovative initiatives aimed at renewal and the search for new opportunities. In addition, following the indications of Podsakoff et al. (2003), design solutions were adopted to minimize the possible impact of common method variance. Examples of measures taken in this study are ensuring anonymity, reducing item ambiguity, separating pages measuring independent and dependent variables, encouraging honest responses with no right or wrong answers, and including verbal labels with scale endpoints and midpoints. Ex post tests only provided weak values for one of the items from the information interpretation scale.

Another limitation of the study lies in its cross-sectional nature. It is possible to establish associations between variables but not clear cause-effect linkages. To resolve this problem, longitudinal studies are required to analyze the effects of high-performance work systems over time. Such a focus is relevant given that HR practices designed to promote intrapreneurship require time to be implemented, as well as considerable effort to be perceived and interpreted correctly and to influence behaviors and outcomes.

Also, intended high-performance work systems (i.e., “intended policies”) may differ substantially from real “implemented policies” and employees’ subjective interpretations (i.e., “perceived policies”). These perceptions can directly affect employee attitudes and behaviors and hence outcomes. In this scenario, middle managers are crucial, not only because of the impact of their support for employee initiatives (as discussed earlier) but also because of their role in the implementation of high-performance work systems. Substantial inter-group differences may be derived from this situation (i.e., differences between groups of employees reporting to different middle managers). Hence, it would be advisable to use multilevel analyses to explore (at least) high-performance work systems perceived at the individual level, as well as possible differences at the group, department, or organization levels. These analyses should also explore the effects of high-performance work systems on knowledge management processes and intrapreneurial behavior. Finally, comparative analysis of the proposed relationships using similar samples in different countries with substantially different cultures would be another important line of research in the future, especially in relation to the moderating effect of supervisor support.

Finally, the removal of items measuring the concept of risk-taking is also a limitation of the study because it led to the omission of one of the three dimensions used to define intrapreneurial behavior. This issue was discussed with scholars from the research teams involved in the study, as well as executives from the participating banks. Their comments, together with the fact that Ecuadorian society has high power distance (78) and uncertainty avoidance (67), lead to several conclusions. First, in general, employees show little inclination to take risks, especially considering that the companies used in this study are strongly hierarchical and formalized. Second, taking large risks for a large return when facing adversity or acting first and asking for approval later (RISK2 and RISK3) are not considered appropriate behaviors by the average employee. Third, the process of researching, providing, promoting, and proposing new ideas seems to be more in line with what these companies and society consider appropriate behavior within an organizational structure. Further analysis in this area by considering cultural differences and organizational design elements could offer an interesting line of research.

References

Adachi T, Hisada T (2017) Gender differences in entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship: an empirical analysis. Small Bus Econ 48:447–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9793-y

Agarwala T (2003) Innovative human resource practices and organizational commitment: an empirical investigation. Int J Hum Resour Manag 14(2):175–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/0958519021000029072

AlEssa HS, Durugbo CM (2022) Understanding innovative work behaviour of women in service firms. Serv Bus 16(4):825–862. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-022-00501-z

Alfes K, Shantz AD, Bailey C, Conway E, Monks K, Fu N (2019) Perceived human resource system strength and employee reactions toward change: revisiting human resource’s remit as change agent. Hum Resour Manage 58(3):239–252. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21948

Appelbaum E, Bailey LM, Griffeth RW (2000) Manufacturing advantage: why high-performance work systems pay off. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Arthur JB, Boyles T (2007) Validating the human resource system structure: a levels-based strategic HRM approach. Hum Resour Manag Rev 17(1):77–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2007.02.001

Ashforth BE, Mael F (1989) Social identity theory and the organization. Acad Manag Rev 14(1):20–39. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4278999

Audretsch DB, Belitski M, Caiazza R, Lehmann EE (2020) Knowledge management and entrepreneurship. Int Entrepreneurship Manag J 16(2):373–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00648-z

Ben Hador B, Klein G (2020) Act your age? Age, intrapreneurial behavior, social capital and performance. Employee Relat 42(2):349–365. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-01-2019-0059

Berzin S, Pitt-Catsouphes M, Gaitan-Rossi P (2016) Innovation and sustainability: an exploratory study of intrapreneurship among human service organizations. Hum Service Org 40(5):540–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2016.1184207

Blanka C (2019) An individual-level perspective on intrapreneurship: a review and ways forward. RMS 13(5):919–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-018-0277-0

Boxall P, Purcell J (2003) Strategy and human resource management. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Brand M, Tiberius V, Bican PM, Brem A (2021) Agility as an innovation driver: towards an agile front end of innovation framework. RMS 15(1):157–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-019-00373-0

Cabrera EF, Cabrera A (2005) Fostering knowledge sharing through people management practices. Int J Hum Resour Manag 16(5):720–735. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190500083020

Cai W, Lysova EI, Bossink BA, Khapova SN, Wang W (2019) Psychological capital and self-reported employee creativity: the moderating role of supervisor support and job characteristics. Creat Innov Manag 28(1):30–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12277

Camelo-Ordaz C, García-Cruz J, Sousa-Ginel E, Valle-Cabrera R (2011) The influence of human resource management on knowledge sharing and innovation in Spain: the mediating role of affective commitment. Int J Hum Resour Manag 22(07):1442–1463. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.561960

Camelo-Ordaz C, Fernández-Alles M, Ruiz-Navarro J, Sousa-Ginel E (2012) The intrapreneur and innovation in creative firms. Int Small Bus J 30(5):513–535. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242610385396

Canet-Giner MT, Redondo-Cano A, Escriba-Carda N, Balbastre-Benavent F, Revuelto-Taboada L, Saorín-Iborra MC (2020) Prácticas de recursos humanos y comportamiento intraemprendedor: La influencia del género en esta relación. TEC Empresarial 14(1):12–25. https://doi.org/10.18845/te.v14i1.4952

Canet-Giner MT, Redondo-Cano A, Balbastre-Benavent F, Escribá-Carda N, Revuelto-Taboada L, Saorin-Iborra MC (2022) The influence of clustering on HR practices and intrapreneurial behavior. Compet Rev 32(1):35–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/CR-10-2019-0102

Chae H, Park J, Choi JN (2019) Two facets of conscientiousness and the knowledge sharing dilemmas in the workplace: contrasting moderating functions of supervisor support and coworker support. J Organ Behav 40(4):387–399. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2337

Chang E, Chin H (2018) Signaling or experiencing: commitment HRM effects on recruitment and employees’ online ratings. J Bus Res 84:175–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.11.002

Chouchane R, St-Jean É (2022) Job anxiety as psychosocial risk in the relationship between perceived organizational support and intrapreneurship in SMEs. Innovation. https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2022.2029708

Cohen J (2013) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Elsevier Science, Burlington

Combs J, Liu Y, Hall A, Ketchen D (2006) How much do high-performance work practices matter? A meta-analysis of their effects on organizational performance. Pers Psychol 59(3):501–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00045.x

Cooke FL, Xiao M, Chen Y (2021) Still in search of strategic human resource management? A review and suggestions for future research with China as an example. Hum Resour Manag 60(1):89–118. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22029

Cropanzano R, Mitchell MS (2005) Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review. J Manag 31(6):874–900

Crossan MM, Berdrow I (2003) Organizational learning and strategic renewal. Strateg Manag J 24(11):1087–1105. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.342

Currie G, Kerrin M (2003) Human resource management and knowledge management: enhancing knowledge sharing in a pharmaceutical company. Int J Hum Resour Manag 14(6):1027–1045. https://doi.org/10.1080/0958519032000124641

Dal Zotto C, Gustafsson V (2008) Human resource management as an entrepreneurial tool. In: Barrett R, Mayson S (eds) International handbook of entrepreneurship and HRM. Edward Elgar publishing, Cheltenham (UK), pp 89–110

De Jong JP, Parker SK, Wennekers S, Wu C (2011) Corporate entrepreneurship at the individual level: measurement and determinants. EIM Res Rep Zoetermeer 11(13):3–27

De Jong JP, Parker SK, Wennekers S, Wu CH (2015) Entrepreneurial behavior in organizations: does job design matter? Entrep Theory Pract 39(4):981–995. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12084

De Roeck K, El Akremi A, Swaen V (2016) Consistency matters! How and when does corporate social responsibility affect employees’ organizational identification? J Manag Stud 53(7):1141–1168. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12216

Del Giudice M, Della Peruta MR (2016) The impact of IT-based knowledge management systems on internal venturing and innovation: a structural equation modeling approach to corporate performance. J Knowl Manag 20(3):484–498. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-07-2015-0257

Delery JE, Shaw JD (2001) The strategic management of people in work organizations: review, synthesis, and extension. In: Buckley MR, Wheeler AR, Halbesleben JRB (eds) Research in personnel and human resources management. Emerald, Leeds, pp 165–197

Dickson PH, Solomon GT, Weaver KM (2008) Entrepreneurial selection and success: does education matter? J Small Bus Enterp Dev 15(2):239–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000810871655

Drucker P (2002) Managing in the next society. Truman Talley Books, New York

Edvardsson IR (2008) HRM and knowledge management. Empl Relat 30(5):553–561. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450810888303

Eisenberger R, Huntington R, Hutchinson S, Sowa D (1986) Perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol 71(3):500–507. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

El-Said OA, Al Hajri B, Smith M (2020) An empirical examination of the antecedents of training transfer in hotels: the moderating role of supervisor support. Int J Contemp Hosp Managt 32(11):3391–3417. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2020-0262

Escribá-Carda N, Balbastre-Benavent F, Canet-Giner MT (2017) Employees’ perceptions of high-performance work systems and innovative behaviour: the role of exploratory learning. Eur Manag J 35(2):273–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.11.002

Escribá-Carda N, Revuelto-Taboada L, Canet-Giner MT, Balbastre-Benavent F (2020) Fostering intrapreneurial behavior through human resource management system. Balt J Manag 15(3):355–373. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-07-2019-0254

Evans C (2003) Managing for knowledge: HR’s strategic role. Butterworth-Heinemann, Amsterdam

Farrukh M, Khan MS, Raza A, Shahzad IA (2021) Influence of high-performance work systems on intrapreneurial behavior. J Sci Technol Policy Manag 12(4):609–626

Flores LG, Zheng W, Rau D, Thomas CH (2012) Organizational learning: subprocess identification, construct validation, and an empirical test of cultural antecedents. J Manag 38(2):640–667. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310384631

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

Gould-Williams J, Davies F (2005) Using social exchange theory to predict the effects of HRM practice on employee outcomes: an analysis of public sector workers. Public Manag Rev 7(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/1471903042000339392

Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hayton JC (2005) Promoting corporate entrepreneurship through human resource management practices: a review of empirical research. Hum Resour Manag Rev 15(1):21–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2005.01.003

Hayton JC, Hornsby JS, Bloodgood J (2013) Entrepreneurship: a review and agenda for future research. Management 16(4):381–409

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43(1):115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hirst G, Van Knippenberg D, Zhou J (2009) A cross-level perspective on employee creativity: goal orientation, team learning behavior, and individual creativity. Acad Manag J 52(2):280–293. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.37308035

Hofstede G (2022) The 6 dimensions model of national culture. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/. Accessed 4 April 2022.

Igbudu N, Garanti Z, Popoola T (2018) Enhancing bank loyalty through sustainable banking practices: the mediating effect of corporate image. Sustainability 10(11):1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114050

Jackson SE, Schuler RS, Jiang K (2014) An aspirational framework for strategic human resource management. Acad Manag Ann 8(1):1–56. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2014.872335

Jahanshahi AA, Nawaser K, Brem A (2018) Corporate entrepreneurship strategy: an analysis of top management teams in SMEs. Balt J Manag 13(4):528–543. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-12-2017-0397

Janssen O (2005) The joint impact of perceived influence and supervisor supportiveness on employee innovative behavior. J Occup Organ Psychol 78:573–579. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X25823

Jensen JM, Patel PC, Messersmith JG (2013) High-performance work systems and job control: consequences for anxiety, role overload, and turnover intentions. J Manag 39(6):1699–1724. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311419663

Jiang K, Lepak DP, Baer HuJ (2012) How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? A meta-analytic investigation of mediating mechanisms. Acad Manag J 55(6):1264–1294. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0088

Jung HS, Yoon HH (2017) Error management culture and turnover intent among food and beverage employees in deluxe hotels: the mediating effect of job satisfaction. Serv Bus 11(4):785–802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-016-0330-5

Kamdar D, Van Dyne L (2007) The joint effects of personality and workplace social exchange relationships in predicting task performance and citizenship performance. J Appl Psychol 92(5):1286–1298. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1286

Kehoe RR, Wright PM (2013) The impact of high-performance human resource practices on employees’ attitudes and behaviors. J Manag 39(2):366–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310365901

Kock N (2015) Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. Int J e-Collab 11(4):1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

Kock N, Lynn G (2012) Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: an illustration and recommendations. J Assoc Inf Syst 13(7):1–40

Kraus S, Breier M, Jones P, Hughes M (2019) Individual entrepreneurial orientation and intrapreneurship in the public sector. Int Entrepreneurship Manag J 15(4):1247–1268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-019-00593-6

Kühn C, Eymann T, Urbach N, Schweizer A (2016) From professionals to entrepreneurs: human Resources practices as an enabler for fostering corporate entrepreneurship in professional service firms. Ger J Hum Resour Manag 30(2):125–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002216632134

Kuratko DF, Ireland RD, Covin JG, Hornsby JS (2005) A model of middle–level managers’ entrepreneurial behavior. Entrep Theory Pract 29(6):699–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00104.x

Kuvaas B, Dysvik A (2010) Exploring alternative relationships between perceived investment in employee development, perceived supervisor support and employee outcomes. Hum Resour Manag J 20(2):138–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2009.00120.x

Lepak DP, Snell SA (2002) Examining the human resource architecture: the relationships among human capital, employment, and human resource configurations. J Manag 28(4):517–543. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630202800403

Lertxundi A, Landeta J (2011) Estrategia Competitiva y Sistemas de Trabajo de Alto Rendimiento. Revista Europea De Dirección y Economía De La Empresa 20(2):73–86

Lin HF (2007) Knowledge sharing and firm innovation capability: an empirical study. Int J Manpow 28(3–4):315–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720710755272

Lin FY (2022) Effectiveness of the talent cultivation training program for industry transformation in Taiwan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Serv Bus 16(3):529–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-021-00455-8

Lin HF, Lee GG (2006) Effects of socio-technical factors on organizational intention to encourage knowledge sharing. Manag Decis 44(1):74–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740610641472

Liu CH, Lee T (2015) Promoting entrepreneurial orientation through the accumulation of social capital, and knowledge management. Int J Hosp Manag 46:138–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.01.016

Liu F, Chow IHS, Huang M (2020) High-performance work systems and organizational identification: the mediating role of organizational justice and the moderating role of supervisor support. Pers Rev 49(4):939–955. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-10-2018-0382

Ma Z, Long L, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Lam CK (2017) Why do high-performance human resource practices matter for team creativity? The mediating role of collective efficacy and knowledge sharing. Asia Pac J Manag 34(3):565–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-017-9508-1

Madu UO, Urban B (2014) An empirical study of desired versus actual compensation practices in determining intrapreneurial behaviour. SA J Hum Resour Manag 12(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v12i1.592

Malik A, Froese FJ, Sharma P (2020) Role of HRM in knowledge integration: towards a conceptual framework. J Bus Res 109:524–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.029

McDonald LM, Lai CH (2011) Impact of corporate social responsibility initiatives on Taiwanese banking customers. Int J Bank Market 29(1):50–63. https://doi.org/10.1108/02652321111101374

Messersmith JG (2008) Transforming caterpillars into butterflies: the role of managerial values and HR systems in the performance of emergent organizations. University of Kansas, Lawrence

Messersmith JG, Wales WJ (2013) Entrepreneurial orientation and performance in young firms: the role of human resource management. Int Small Bus J 31(2):115–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242611416141

Meyer RD, Dalal RS, Hermida R (2010) A review and synthesis of situational strength in the organizational sciences. J Manage 36(1):121–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309349309

Minbaeva DB (2013) Strategic HRM in building micro-foundations of organizational knowledge-based performance. Hum Resour Manag Rev 23(4):378–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2012.10.001

Mustafa M, Lundmark E, Ramos HM (2016) Untangling the relationship between human resource management and corporate entrepreneurship: the mediating effect of middle managers’ knowledge sharing. Entrep Res J 6(3):273–295. https://doi.org/10.1515/erj-2015-0004

Neessen P, Caniëls MC, Vos B, De Jong JP (2019) The intrapreneurial employee: toward an integrated model of intrapreneurship and research agenda. Int Entrepreneurship Manag J 15(2):545–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-018-0552-1

Newman A, Miao Q, Hofman PS, Zhu CJ (2016) The impact of socially responsible human resource management on employees’ organizational citizenship behaviour: the mediating role of organizational identification. Int J Hum Resour Manag 27(4):440–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1042895

Obeidat SM, Mitchell R, Bray M (2016) The link between high performance work practices and organizational performance: empirically validating the conceptualization of HPWP according to the AMO model. Empl Relat 38(4):578–595. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-08-2015-0163

OECD (2005) Oslo manual, guidelines for collecting and interpreting innovation data, the measurement of scientific and technological activities. OECD Publications, Paris

Oltra V (2005) Knowledge management effectiveness factors: the role of HRM. J Knowl Manag 9(4):70–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270510610341

Ostroff C, Bowen DE (2016) Reflections on the 2014 Decade Award: Is There Strength in the Construct of HR System Strength? Acad Manage Rev 41(2):196–214. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2015.0323

Palacios D, Gil I, Garrigos F (2009) The impact of knowledge management on innovation and entrepreneurship in the biotechnology and telecommunications industries. Small Bus Econ 32(3):291–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9146-6

Parker SC (2011) Intrapreneurship or entrepreneurship? J Bus Ventur 26(1):19–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.07.003

Parker SK, Collins CG (2010) Taking stock: Integrating and differentiating multiple proactive behaviors. J Manag 36(3):633–662. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308321554

Piening EP, Baluch AM, Ridder HG (2014) Mind the intended-implemented gap: understanding employees’ perceptions of HRM. Hum Resour Manag 53(4):545–567. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21605

Podsakoff PM, Organ DW (1986) Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J Manag 12(4):531–544

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff LJY, NP, (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Rabl T, Jayasinghe M, Gerhart B, Kühlmann TM (2014) A meta-analysis of country differences in the high-performance work system–business performance relationship: the roles of national culture and managerial discretion. J Appl Psychol 99(6):1011–1041. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037712

Razavi SH, Ab Aziz K (2017) The dynamics between entrepreneurial orientation, transformational leadership, and intrapreneurial intention in Iranian R&D sector. Int J Entrep Behav Res 23(5):769–792. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-10-2016-0337

Rehman WU, Ahmad M, Allen MM, Raziq MM, Riaz A (2019) High involvement HR systems and innovative work behaviour: the mediating role of psychological empowerment, and the moderating roles of manager and co-worker support. Eur J Work Organ Psy 28(4):525–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1614563