Abstract

Background

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common chronic liver disease in the world. The increasingly sedentary lifestyle in recent years may have accelerated the development of NAFLD, independent of the level of physical activity.

Objective

The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to determine the association between leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) and time spent sitting (TSS) and the likelihood of developing NAFLD in a sample of men and women aged 18–64 years, from southern Italy.

Design

The study is based on two cohort studies, a randomized clinical trial and an observational cost-benefit study.

Participants

A total of 1269 participants (51.5% women) drawn from 3992 eligible subjects were enrolled in this study.

Exposures

Leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) and time spent sitting (TSS) were assessed using the Italian long form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-LF), designed for administration to adults aged 18 to 65 years.

Main Measures

The association of exposures with the probability of belonging to a certain NAFLD degree of severity.

Key Results

The probability of having mild, moderate, and severe NAFLD tends to decrease with increasing LTPA and decreasing TSS levels. We selected a combination of participants aged 50 years and older stratified by gender. Men had a statistically significant difference in the probability of developing moderate NAFLD if they spent 70 h per week sitting and had low LTPA, while among women there was a statistically significant difference in the probability of developing mild or moderate NAFLD if they had moderate LPTA and spent 35–70 h/week sitting.

Conclusions

The study thus showed that the amount of LTPA and the amount of TSS are associated with development and progression of NAFLD, but this relationship is not a linear one—especially in women aged ≥ 50 years old.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common chronic liver disease in the world1 and encompasses a broad spectrum of liver diseases, ranging from simple steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.2,3 In recent years, time spent sitting has increased significantly, leading to a rising prevalence of obesity and NAFLD. This association has significant public health implications4 on the management of the disease. In the absence of sufficient drug treatment, lifestyle modifications are effective during the treatment of NAFLD: diet and physical activity are factors that play a key role in the pathogenesis and progression of NAFLD.5,6 Regular practice of physical activity promotes calorie consumption, whereas low levels of physical activity can worsen the condition of NAFLD.7 The protective effect of physical activity on the incidence and mortality of several chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, stroke, and several types of cancer, is well known.8 Recently, the deleterious effects of sedentary behavior, independently of leisure-time physical activity, have received much attention. In fact, several epidemiological studies have suggested a positive association between sedentary behavior and obesity, diabetes, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mortality other than that associated with little physical activity.9,10,11,12,13,14 This association, which was more pronounced in subjects with high levels of physical activity (moderate to vigorous), indicates, however, that regular physical activity does not fully protect against risk when associated with prolonged sedentary behaviour.15 Therefore, we might hypothesize that prolonged sedentary behavior, regardless of the level of physical activity, even in leisure time, may play a potential role in the development and progression of NAFLD. The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to explore the likelihood of developing NAFLD by associating leisure-time physical activity with time spent sitting in a sample of men and women aged 18 to 64 years, from southern Italy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and Study Design

This was a cross-sectional study conducted at the National Institute of Gastroenterology “S. de Bellis” (Castellana Grotte, Bari, Italy). The study was based on four studies whose details have been published elsewhere, two being cohort studies, one a randomized clinical trial and one a cost-benefit observational study. We chose to assemble the four studies to account for the geographic differences that characterized the two cohorts, and the study design that provided for different inclusion criteria. In this way, we hypothesized that the heterogeneity of the participants could produce more robust results.

Briefly, the MICOL study (Italian Multicenter Colelithiasis Study) is an ongoing prospective cohort study assembled in 1985 based on a random sample of the Castellana Grotte (Apulian Region, Italy) population aged ≥ 30 years old. The participants were followed up in 1992–1993, 2005–2006, and 2017–2020; the last follow-up was stopped due to COVID-19 restrictions. The main objective of the study was to estimate the prevalence of cholelithiasis and its risk factors but also to probe other liver diseases. The study retrospectively showed a high prevalence of hepatitis C infection and NAFLD.16 In this study, we considered only the 2017–2020 follow-up.

NUTRIHEP (Nutrition and Hepatology) is an ongoing prospective cohort study assembled in 2005–2006 based on a random sample of the Putignano (Apulian Region, Italy) population aged ≥ 18 years old. The aim of this survey was to estimate the prevalence of several liver diseases as well as to find out population dietary patterns. The study showed a low prevalence of hepatitis B and C infection and a high prevalence of NAFLD.17 The first follow-up was carried out between April 2015 and May 2019.

The NUTRIATT study was a randomized clinical trial (www.https://clinicaltrials.gov, registration number CT02347696), conducted from March 2015 to December 2016. The study enrolled participants aged > 29 to < 60 years old, randomly assigned to six different treatments consisting of a diet, two different physical activity programs, and their combination lasting 6 months. All interventions were useful to reduce NAFLD scores but the combination of low glycemic Mediterranean diet (LGIMD) and an aerobic physical activity program was the most efficient combination.18 For this study, we took baseline data.

The COST-BENEFIT was an observational study conducted from March 2018 to February 2020. In this study, participants aged 18–65 years old, suffering from hypertension, dyslipidemia, or type II diabetes or insulin resistance, were recruited. Participants were asked to follow a diet and a personalized physical activity program lasting 1 year. The study was stopped because of the restrictions of COVID-19. The aim of this study was to probe the benefits of a LGIMD and a mixed exercise program on metabolic-associated fatty liver disease. LGIMD and the mixed exercise program significantly improved metabolic-associated fatty liver disease status; in addition, longitudinal body mass index and HOMA-IR measurements were good predictors of the disappearance of diagnostic criteria for metabolic-associated fatty liver disease.19 For this study, we took baseline data.

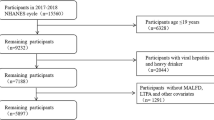

The flowchart of the studies, with the number of subjects and other details, is shown in Fig. 1.

All the studies were approved by the Ethics Committee and were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All subjects signed informed consent.

Data Collection

In all the studies, trained staff collected data using questionnaires and standardized procedures. Socio-demographic, anthropometric, nutritional, health-related, and lifestyle data were collected. Blood pressure was assessed following international guidelines. Anthropometric measurements (weight, height, waist circumference) were taken in standard manner. Weight and height measurements were taken using SECA instruments (Model 700 and Model 206; 220 cm; SECA, Hamburg, Germany). NAFLD assessment and grading were performed by ultrasound examination (LUS) in the MICOL, NUTRIHEP, and COST-BENEFIT studies and by controlled attenuation parameter in the NUTRIATT study. Fasting blood samples were drawn in the morning and collected in tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (K-EDTA) anticoagulant. Biochemical measurements were performed using standard methods. The following biomarkers were evaluated in all studies: HbA1c, glucose, AST, ALT, GGT, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, insulin, HOMA-IR, CRP. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire - Long Form (IPAQ-LF) was self-administered in all studies, but staff provided assistance in reading the questionnaire if needed. All measured values are shown in Table 1.

Exposure Assessment

The Italian long form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-LF)20 was used in all these studies, designed for administration to adults aged 18–65 years. IPAQ-LF was self-administered with the assistance of the staff in reading the questionnaire, if needed, to avoid missing and inconsistent values and reduce classification bias. Other than demographic and social characteristics, the questionnaire probes the following domains: household and garden work activities, occupational activity, self-transport, leisure-time physical activity, time spent sitting, and hours of sleep. An additional question was asked about the rate of walking and cycling. Coding and processing were performed following the indications contained in the User Guide of the IPAQ webpage. The information about LTPA was expressed as METxMinutexDay/Week-1 and TSS as h/week.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data analysis was performed using means (SD) and frequencies (%) as appropriate. For descriptive and analytical purposes, exposure assessment was categorized as follows: PA leisure (Met*Min*Week-1) low (< 600), moderate (600–3000), and high (≥ 3000) and time spent sitting (h/week): < 35, 35–70, and > 70.

Subsequently, due to the ordinal scale of the NAFLD degree of severity, a multivariable ordinal logistic model (OLM) was fitted to the data. PA leisure and time spent sitting, the exposure variables, were introduced in the model as principal effects and as modification effects between them. Age (< 50/≥ 50), sex (male vs. female), AST, ALT, daily calorie intake, PCR, and HbA1c were used as adjusting variables.

Results are expressed as odds ratios (ORs) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) which estimate the association between the exposures and NAFLD in each of the degrees of severity. The estimated cut-off values for the categories of NAFLD are also expressed as ORs. Using post-estimation tools, the parallel regression assumption was tested by means of the test of Brant (overall test and single variable test), as well as the prediction of probabilities of belonging to each of the exposure categories, and their combination were obtained and then graphically displayed. Moreover, as a result of the OLM, marginal probabilities of some ideal patterns of covariates were estimated and the differences among them were tested. We chose the combination of age and sex as previous results had indicated that this population reached a maximum body mass index between 50 and 60 years old with a higher prevalence of overweight among men.21

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 18.1 (StataCorp LLC, StataCorp, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA). In particular, the estimate command -ologit- and the post-estimation commands -predict-, -Brant-, -mtable-, and -mlincom- were used.22

RESULTS

A description of the enrolled sample is shown in Table 1. In total, 1269 (51.5% women) participants selected among 3992 eligible subjects were enrolled in this study. Characteristics of eligible and enrolled subjects are shown in Table 1. All enrolled subjects were younger than 66 years old as the instrument used to measure the exposure was validated for the range 18–65 years old. The mean age was 52.47 (7.83) years and about 50% of the participants belonged to the 51–60 years old category; 53.8% had a diagnosis of NAFLD. Most of the participants were married or engaged in stable relationships (85.2%), had secondary school or a higher level of education (91.7%), and were Crafts, Agricultural and Sales Workers (48.4%). Biochemical markers and anthropometrics characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Results from OLM are shown in Table 2. The Brant test of the parallel regression assumption held. There were no principal significant effects of LTPA and TSS. However, there were statistically significant decreased ORs for the modification effect of low LTPA leisure/< 35 h sitting/week (OR 0.30, 95% CI 0.10,0.87), moderate LTPA leisure/< 35 h sitting/week (OR 0.29, 95% CI 0.10, 0.83), high LTPA leisure/35–70 h sitting/week (OR 0.31, 95% CI 0.10,0.94), and high LTPA leisure/< 35 h sitting/week (OR 0.23, 95% CI 0.07,0.68) on NAFLD degree of severity. Post-estimation predicted probabilities are graphically displayed in Fig. 2. As can be seen, the probability of not developing NAFLD is associated with the PA level and sitting time (panel a): the higher the PA level and the lower the time spent sitting, the higher the probability of not developing NAFLD. For mild (panel b), moderate (panel c), and severe (panel d) NAFLD, there is a decreasing trend in the probability of developing NAFLD as the LTPA level increases and time spent sitting decreases. Estimated probabilities of some patterns of covariates and differences in probabilities among them are shown in Table 3. We chose the combination of participants aged 50 years old or older stratified by sex and belonging to the four outcome categories with a low or medium level of PA who spent 70 h/week sitting as compared with those who spent 35–70 h/week sitting. Men had a statistically significant difference in probability of developing moderate NAFLD if they spent 70 h/week sitting and had a low level of PA whereas among women there were statistically significant probability differences of developing mild or moderate NAFLD if they had medium PA and spent 35–70 h/week sitting.

DISCUSSION

There is strong evidence of the benefits of physical activity.23,24 The regular practice of PA reduces the risk of premature mortality and is an effective primary and secondary prevention strategy for at least 25 chronic diseases.25,26 However, more than a quarter of the adult population worldwide27,28 is not sufficiently physically active, and several studies have shown that sedentary behavior and low levels of leisure-time physical activity are associated with negative health outcomes.4,10,29,30 Our study showed that subjects who spend less time sitting during leisure time are more likely to remain NAFLD-free regardless of the level of PA and, those who spend more time sitting during leisure time are more likely to develop more severe forms of NAFLD (mild to severe) when this is accompanied especially with low levels of LTPA, particularly among women aged 50 years old or more. The mechanisms by which sedentary behavior contributes to a higher prevalence of NAFLD, regardless of the level of physical activity, are still uncertain. Similar results to ours have been obtained by previous correlation studies that have identified an association between sedentary behavior and metabolic syndrome, regardless of physical activity levels.31,32,33,34,35,36 Indeed, cross-sectional studies have shown that increased sedentary behavior and low physical activity levels are a key problem at population level and consequently could play a potential role in the development of NAFLD, independently of physical activity.37,38,39,40 The results of our study show that the amount of time spent sitting and the amount of physical activity performed in leisure time are not linearly associated with the occurrence and degree of severity of NAFLD. The greater the sedentary time, the greater the probability of developing more severe forms of NAFLD. As a consequence and, although the inverse relationship between PA and NAFLD is well established in the literature, our results show that these benefits are not sufficient for individuals who spend a lot of time sitting, as sitting continuously during work or leisure can alter some metabolic parameters and increase overall inflammatory processes.41 However, it is possible to diminish inflammation by taking short breaks during sitting42, to obtain other health benefits.43 Indeed, NAFLD is closely related to unhealthy lifestyles and the positive association between sitting time and NAFLD could also be explained as the consequence of a higher calorie intake and/or lower energy expenditure, resulting in the development of obesity or at any rate weight gain, and an elevated risk of NAFLD.8,43,44,45 In addition, the WHO has drawn up recommendations for leisure-time physical activity to reduce the likelihood of NAFLD development and progression, regardless of shared risk factors.5,46 We chose two ideal covariate patterns to estimate the probability of getting NAFLD. In previous studies21, we showed a sharp increase in the BMI in persons aged 50 years or older, reaching a maximum at 64.8 years old in this population, with a statistically significant effect of sex. As NAFLD is a correlate of obesity, we took these parameters to estimate and test the difference in probability among subjects with different degrees of leisure-time PA and time spent sitting. Globally, the NAFLD prevalence is higher in men although recent reports show a trend to increasing NAFLD among women.47,48 In fact, men were likely to develop moderate NAFLD if they had a low level of physical activity and spent 70 h/week sitting; women, on the other hand, were likely to develop mild to moderate NAFLD if they had a moderate level of physical activity and spent 35/70 h/week sitting. In our study, the results also show that the probability of developing NAFLD is different between men and women aged ≥ 50. The higher prevalence in NAFLD among men is reduced or nullified in women after menopause.49,50 The mechanisms underlying this changing risk pattern among pre- and postmenopausal women remain incompletely understood. Several mechanisms have been hypothesized, ranging from findings in animal models to studies in human beings. In animal models, it has been shown that dietary factors can synergistically enhance estrogen deficiencies leading to increased hepatic injury.51 The loss of protection conferred by estrogens combined with other disorders (abdominal adiposity, metabolic syndrome, microbiota dysregulation, insulin resistance)52,53 could be the underlying conditions leading women to have an increased risk of developing NAFLD as well as other metabolic diseases.54,55 Moreover, the relative androgen increase during menopause could contribute to the development of NAFLD.56 Some methodological issues need to be considered. The strength of this study is the large number of subjects enrolled. Despite the exclusion of subjects due to missing information, we can assume that the number of subjects may still be representative of the local population and selection bias should be minor. Limitations of the study are related to self-reported sedentary behavior data, as participants’ activity levels were measured and described only using physical activity questionnaires. However, IPAQ has shown to be resistant to serious differential misclassification bias and, if present, it tends toward the null hypothesis. It is worthy to note that the Apulian population is extremely homogeneous, then the ethnic diversity of this setting does not matter.

CONCLUSIONS

Prolonged sedentary behavior has a greater influence on the development and progression of NAFLD, regardless of levels of leisure-time physical activity. In women over the age of 50, this association is probably more evident due to hormonal changes after menopause. However, it is possible to mitigate the deleterious effects of prolonged sedentary behavior by taking short breaks during sessions, and so also to gain benefit from the protective effect of PA.

Data Availability

All data are available by contacting the corresponding author.

References

Sayiner M, Koenig A, Henry L, Younossi ZM. Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in the United States and the Rest of the World. Clin Liver Disease 2016, 20, 205-214, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cld.2015.10.001.

Adams LA, Sanderson S, Lindor KD, Angulo P. The Histological Course of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Longitudinal Study of 103 Patients with Sequential Liver Biopsies. J Hepatol 2005, 42, 132-138, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2004.09.012.

Caldwell SH, Crespo DM. The Spectrum Expanded: Cryptogenic Cirrhosis and the Natural History of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Hepatol 2004, 40, 578-584, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2004.02.013.

Saunders TJ, McIsaa T, Douillette K, Gaulton N, Hunter S, Rhodes RE et al. Sedentary Behaviour and Health in Adults: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme 2020, 45, S197-s217, https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2020-0272.

Romero-Gómez M, Zelber-Sagi S, Trenell M. Treatment of NAFLD with diet, Physical Activity and Exercise. J Hepatol 2017, 67, 829-846, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.05.016.

Fernández T, Viñuela M, Vidal C, Barrera F. Lifestyle Changes in Patients with Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. PloS One 2022, 17, e0263931, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263931.

Yabe Y, Kim T, Oh S, Shida T, Oshida N, Hasegawa et al. Relationships of Dietary Habits and Physical Activity Status with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Featuring Advanced Fibrosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18178918.

Prince SA, Rasmussen CL, Biswas A, Holtermann A, Aulakh T, Merucci K et al. The Effect of Leisure Time Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour on the Health of workers with Different Occupational Physical Activity Demands: A Systematic Review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2021, 18, 100, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-021-01166-z.

Dunstan DW, Barr EL, Healy GN, Salmon J, Shaw JE, Balkau B et al. Television Viewing Time and Mortality: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab). Circulation 2010, 121, 384-391, https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.109.894824.

Hamilton MT, Hamilton DG, Zderic TW. Role of Low Energy Expenditure and Sitting in Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, type 2 Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease. Diabetes 2007, 56, 2655-2667, https://doi.org/10.2337/db07-0882.

Hu FB, Li TY, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Manson JE. Television Watching and other Sedentary Behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. Jama 2003, 289, 1785-1791, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.14.1785.

van Uffelen JG, Wong J, Chau, JY, van der Ploeg HP, Riphagen I, Gilson,N.D, et al. Occupational Sitting and Health Risks: a Systematic Review. Am J Prevent Med 2010, 39, 379-388, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.024.

Patel AV, Bernstein L, Deka A, Feigelson HS, Campbell PT, Gapstur SM,et al. Leisure Time Spent Sitting in Relation to Total Mortality in a Prospective Cohort of US Adults. Am J Epidemiol 2010, 172, 419-429, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq155.

Wijndaele K, Brage S, Besson H, Khaw KT, Sharp SJ, Luben R, et al. Television Viewing Time Independently Predicts all-cause and Cardiovascular Mortality: the EPIC Norfolk study. Int J Epidemiol 2011, 40, 150-159, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq105.

Akins JD, Crawford CK, Burton HM, Wolfe AS, Vardarli E, Coyle EF. Inactivity Induces Resistance to the Metabolic Benefits Following Acute Exercise. J App Physiol (Bethesda, Md: 1985) 2019, 126, 1088-1094, https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00968.2018.

Misciagna G, Leoci C, Elba S, Petruzzi J, Guerra V, Mossa A, Noviello MR, Coviello A, Capece-Minutolo M, Giorgiot I. The Epidemiology of Cholelithiasis In Southern Italy . Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 6(10): 937-942, October 1994.

Cozzolongo R, Osella AR, Elba S, Petruzzi J, Buongiorno G, Giannuzzi V, Leone G, Bonfiglio C, Lanzilotta E, Manghisi OG, Leandro Gioacchino the NUTRIHEP Collaborating Group. Epidemiology of HCV infection in the general population a survey in a Southern Italian Town Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104(11):2740-2746.

Franco I, Bianco A, Mirizzi A, Campanella A, Bonfiglio C, Sorino, et al. Physical activity and low glycemic index mediterranean diet: Main and modification effects on NAFLD score. Results from a randomized clinical trial. Nutrients 2021;13, 66.

Curci R, Bianco A, Franco I, Campanella A, Mirizzi A, Bonfiglio C, Sorino P, at al. The effect of low glycemic index mediterranean diet and combined exercise program on metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: A joint modeling approach. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 4339.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth JF, et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exercise 2003, 35, 1381-1395.

Osella AR, Diaz Mdel P, Cozzolongo R, Bonfiglio C, Franco I, Abrescia DI et al. Overweight and obesity in Southern Italy: Their association with social and life-style characteristics and their effect on levels of biologic markers. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Medicas 2014, 71, 113-124.

Long JS, Freese J. Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata, Stata press: 2006; 7.

Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. Jama 2018, 320, 2020-2028.

Miko HC, Zillmann N, Ring-Dimitriou S, Dorner TE, Titze S, Bauer R. Effects of physical activity on health. Gesundheitswesen (Bundesverband der Arzte des Offentlichen Gesundheitsdienstes (Germany)) 2020;82, S184-S195.

Warburton DE, Bredin SS. Reflections on physical activity and health: what should we recommend? Canadian J Cardiol 2016, 32, 495-504.

Gledhill N, Shephard RJ, Jamnik V, Bredin SS, Warburton DE. Consensus on evidence-based preparticipation screening and risk stratification. Annual Rev Geontol Geriatr 2016, 36, 53-102.

Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Worldwide trends in Insufficient Physical Activity from 2001 to 2016: A Pooled analysis of 358 Population-based Surveys with 1·9 Million Participants. The Lancet. The Lancet Global Health 2018, 6, e1077-e1086, https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(18)30357-7.

Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthol R, Haskell W, Ekelund U. Global Physical Activity Levels: sUrveillance Progress, Pitfalls, and Prospects. Lancet (London, England) 2012, 380, 247-257, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60646-1.

Lanningham-Foster L, Nysse LJ, Levine JA. Labor Saved, Calories Lost: the Energetic Impact of Domestic Labor-saving Devices. Obes Res 2003, 11, 1178-1181, https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2003.162.

Patel AV, Friedenreich CM, Moore SC, Hayes SC, Silver JK, Campbell KL,et al. American College of Sports Medicine Roundtable Report on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Cancer Prevention and Control. Med Sci Sports Exercise 2019, 51, 2391-2402, https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000002117.

Bankoski A, Harris TB, McClain JJ, Brychta RJ, Caserotti P, Chen KY, at al. Sedentary Activity Associated with Metabolic Syndrome Independent of Physical Activity. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 497-503, https://doi.org/10.2337/dc10-0987.

Bertrais S, Beyeme-Ondoua JP, Czernichow S, Galan P, Hercberg S, Oppert JM. Sedentary Behaviors, Physical Activity, and Metabolic Syndrome in Middle-aged French Subjects. Obesity Res 2005, 13, 936-944, https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2005.108.

Chu AH, Moy FM. Associations of Occupational, Transportation, Household and Leisure-time Physical Activity Patterns with Metabolic Risk Factors Among Middle-aged Adults in a Middle-income Country. Prev Med 2013, 57 Suppl, S14-17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.12.011.

Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA, Davies MJ, Gorely T, Gray LJ, at al. Sedentary Time in Adults and the Association with Diabetes, cArdiovascular Disease and Death: Systematic Review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 2895-2905, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-012-2677-z.

Ford ES. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome defined by the International Diabetes Federation among adults in the US. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 2745-2749.

Owen N, Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW. Too Much Sitting: the Population Health Science of Sedentary Behavior. Exercise Sport Sci Rev 2010, 38, 105-113, https://doi.org/10.1097/JES.0b013e3181e373a2.

Perseghin, G, Lattuada G, De Cobelli F, Ragogna F, Ntali G, Esposito, A, et al. Habitual Physical Activity is Associated with Intrahepatic Fat Content in Humans. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 683-688, https://doi.org/10.2337/dc06-2032.

St George A, Bauman A, Johnston A, Farrell G, Chey T, George J. Independent Effects of Physical Activity in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2009, 50, 68-76, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22940.

Zelber-Sagi S, Nitzan-Kaluski D, Goldsmith R, Webb M, Zvibel I, Goldiner I, et al. Role of Leisure-time Physical Activity in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Population-based Study. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2008, 48, 1791-1798, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22525.

Biswas A, Oh PI, Faulkner GE, Bajaj RR, Silver MA, Mitchell MS, Alter DA. Sedentary Time and its Association with Risk for Disease incidence, Mortality, and Hospitalization in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Annals Intern Med 2015, 162, 123-132, https://doi.org/10.7326/m14-1651.

Keating SE, Hackett DA, George J, Johnson NA. Exercise and Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Hepatol 2012, 57, 157-166, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.023.

Kenneally S, Sier JH, Moore JB. Efficacy of Dietary and Physical Activity Intervention in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2017, 4, e000139, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgast-2017-000139.

Howard RA, Freedman DM, Park Y, Hollenbeck A, Schatzkin A, Leitzmann MF. Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and the Risk of Colon and Rectal Cancer in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Cancer Causes Contr: 2008, 19, 939-953, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-008-9159-0.

Ryu S, Chang Y, Jung HS, Yun KE, Kwon MJ, Choi YKim, , et al. Relationship of Sitting Time and Physical Activity with Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Hepatol 2015, 63, 1229-1237, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2015.07.010.

Thoma C, Day CP, Trenell MI. Lifestyle Interventions for the Treatment of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Adults: A Systematic Review. J Hepatol 2012, 56, 255-266, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2011.06.010.

Watts EL, Matthews CE, Freeman JR, Gorzelitz JS, Hong HG, Liao LM, et al. Association of Leisure Time Physical Activity Types and Risks of All-Cause, Cardiovascular, and Cancer Mortality Among Older Adults. JAMA Network Open 2022, 5, e2228510, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.2851047.

Lonardo A, Nascimbeni F, Ballestri S, Fairweather D, Win S, Than TA,et al. Sex Differences in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: State of the Art and Identification of Research Gaps. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2019, 70, 1457-1469 https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.30626.

Arshad T, Golabi P, Paik J, Mishra A, Younossi ZM. Prevalence of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in the Female Population. Hepatol Commun 2019, 3, 74-83, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.1285.

Ballestri S, Nascimbeni F, Baldelli E, Marrazzo A, Romagnoli D, Lonardo A. NAFLD as a Sexual Dimorphic Disease: Role of Gender and Reproductive Status in the Development and Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Inherent Cardiovascular Risk. Adv Ther 2017, 34, 1291-1326, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0556-1.

Fan JG, Zhu, J, Li XJ, Chen L, Li L, Dai F, et al. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Fatty Liver in a General Population of Shanghai, China. J Hepatol 2005, 43, 508-514, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2005.02.042.

Nemoto Y, Toda K, Ono M, Fujikawa-Adachi K, Saibara T, Onishi S, et al. Altered expression of fatty acid-metabolizing enzymes in aromatase-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 2000, 105, 1819-1825, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci9575.

Carrieri L, Osella AR, Ciccacci F, Giannelli G, Scavo MP. Premenopausal Syndrome and NAFLD: A New Approach Based on Gender Medicine. Biomedicines 2022, 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10051184.

Veronese N, Notarnicola M, Osella AR, Cisternino AM, Reddavide R, Inguaggiato R, et al. Menopause Does Not Affect Fatty Liver Severity In Women: A Population Study in a Mediterranean Area. Endoc Metab Immune Disorders Drug Targets 2018, 18, 513-521, https://doi.org/10.2174/1871530318666180423101755.

DiStefano JK. NAFLD and NASH in Postmenopausal Women: Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment. Endocrinology 2020; 161, https://doi.org/10.1210/endocr/bqaa134.

Yuan L, Kardashian A, Sarkar M. NAFLD in women: Unique pathways, biomarkers and therapeutic opportunities. Curr Hepatol Rep 2019, 18, 425-432, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11901-019-00495-9.

Livianna C, Alberto RO, Fausto C, Gianluigi G, Scavo MP. Premenopausal Syndrome and NAFLD: A New Approach Based on Gender Medicine Biomedicines 20;10(5):1184, https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10051184

Funding

Micol4: the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Gastroenterology and Research Hospital “S. de Bellis” in Castellana Grotte, Italy (DDG-CE 782/2013). NutriHep: this work was supported by RC DDG n. 225 30/04/2015. NutriAtt: this work was supported by RC 2012–2014, Linea 4, C 32 (D.D.n.110/2014) and by Apulia Region D.G.R. n. 1159, 28 June 2018 and 2019. COST-BENEFIT: this research was funded in full by Ministry of Health, grant number RC DCS n.864 19/12/2017; RC DDG n. 740 10/10/2018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: I.F. and A.R.O. Methodology: I.F. and A.B. Software: C.B. Validation: I.F. and A.B. Formal analysis: C.B. and A.R.O. Investigation: I.F., A.B., and A.R.O. Data curation: R.C., C.B., and A.C. Writing—original draft preparation: I.F. Writing—review and editing: I.F., A.B., and A.R.O. Supervision: A.R.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Franco, I., Bianco, A., Bonfiglio, C. et al. Leisure-Time Physical Activity, Time Spent Sitting and Risk of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study in Puglia. J GEN INTERN MED (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08804-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08804-9