Abstract

Background

Unmet social needs (SNs) often coexist in distinct patterns within specific population subgroups, yet these patterns are understudied.

Objective

To identify patterns of social needs (PSNs) and characterize their associations with health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) and healthcare utilization (HCU).

Design

Observational study using data on SNs screening, HRQoL (i.e., low mental and physical health), and 90-day HCU (i.e., emergency visits and hospital admission). Among patients with any SNs, latent class analysis was conducted to identify unique PSNs. For all patients and by race and age subgroups, compared with no SNs, we calculated the risks of poor HRQoL and time to first HCU following SNs screening for each PSN.

Patients

Adult patients undergoing SNs screening at the Mass General Brigham healthcare system in Massachusetts, United States, between March 2018 and January 2023.

Main Measures

SNs included: education, employment, family care, food, housing, medication, transportation, and ability to pay for household utilities. HRQoL was assessed using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Global-10.

Key Results

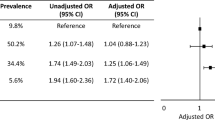

Six unique PSNs were identified: “high number of social needs,” “food and utility access,” “employment needs,” “interested in education,” “housing instability,” and “transportation barriers.” In 14,230 patients with HRQoL data, PSNs increased the risks of poor mental health, with risk ratios ranging from 1.07(95%CI:1.01–1.13) to 1.80(95%CI:1.74–1.86). Analysis of poor physical health yielded similar findings, except that the “interested in education” showed a mild protective effect (0.97[95%CI:0.94–1.00]). In 105,110 patients, PSNs increased the risk of 90-day HCU, with hazard ratios ranging from 1.09(95%CI:0.99–1.21) to 1.70(95%CI:1.52–1.90). Findings were generally consistent in subgroup analyses by race and age.

Conclusions

Certain SNs coexist in distinct patterns and result in poorer HRQoL and more HCU. Understanding PSNs allows policymakers, public health practitioners, and social workers to identify at-risk patients and implement integrated, system-wide, and community-based interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kreuter MW, Thompson T, McQueen A, Garg R. Addressing Social Needs in Health Care Settings: Evidence, Challenges, and Opportunities for Public Health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42:329-44.

Canterberry M, Figueroa JF, Long CL, et al. Association Between Self-reported Health-Related Social Needs and Acute Care Utilization Among Older Adults Enrolled in Medicare Advantage. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(7):e221874.

Rigdon J, Montez K, Palakshappa D, et al. Social Risk Factors Influence Pediatric Emergency Department Utilization and Hospitalizations. J Pediatr. 2022;249:35-42.e4.

McQueen A, Li L, Herrick CJ, et al. Social Needs, Chronic Conditions, and Health Care Utilization among Medicaid Beneficiaries. Popul Health Manag. 2021;24(6):681-90.

Adepoju OE, Liaw W, Patel NC, et al. Assessment of Unmet Health-Related Social Needs Among Patients With Mental Illness Enrolled in Medicare Advantage. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2239855.

Knighton AJ, Stephenson B, Savitz LA. Measuring the Effect of Social Determinants on Patient Outcomes: A Systematic Literature Review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29(1):81-106.

Malapati SH, Edelen MO, Kaur MN, et al. Social determinants of health needs and health-related quality of life among surgical patients: a retrospective analysis of 8512 patients [published online ahead of print, 2023 Oct 6]. Ann Surg. 2023.

Holcomb J, Highfield L, Ferguson GM, Morgan RO. Association of Social Needs and Healthcare Utilization Among Medicare and Medicaid Beneficiaries in the Accountable Health Communities Model. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(14):3692-9.

Mathson LR, Lak KL, Gould JC, Higgins RM, Kindel TL. The Association of Preoperative Food Insecurity With Early Postoperative Outcomes After Bariatric Surgery. J Surg Res. 2024;294:51-57.

Kreuter MW, Garg R, Li L, et al. How Do Social Needs Cluster Among Low-Income Individuals?. Popul Health Manag. 2021;24(3):322-32.

Bisgaier J, Rhodes KV. Cumulative adverse financial circumstances: associations with patient health status and behaviors. Health Soc Work. 2011;36(2):129-37.

Frank DA, Casey PH, Black MM, et al. Cumulative hardship and wellness of low-income, young children: multisite surveillance study. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):e1115-e23.

Thompson T, McQueen A, Croston M, et al. Social Needs and Health-Related Outcomes Among Medicaid Beneficiaries. Health Educ Behav. 2019;46(3):436-44.

Sisodia RC, Dankers C, Orav J, et al. Factors Associated With Increased Collection of Patient-Reported Outcomes Within a Large Health Care System. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4):e202764.

Billious A, Verlander K, Anthony S, Alley D. Standardized Screening for Health-Related Social Needs in Clinical Settings: The Accountable Health Communities Screening Tool. Presented at: National Academy of Medicine; 2017; Washington, DC. Available at https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Standardized-Screening-for-Health-Related-Social-Needs-in-Clinical-Settings.pdf. Accessed September, 2023.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accountable Health Communities Model. The Accountable Health Communities Health-Related Social Needs Screening Tool. 2017. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/files/worksheets/ahcm-screeningtool.pdf. Accessed September, 2023.

Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(7):873-80.

HealthMeasures. PROMIS® Score Cut Points. Available at: https://www.healthmeasures.net/score-and-interpret/interpret-scores/promis/promis-score-cut-points. Accessed September, 2023.

SAS Procedures for Latent Class Analysis & Latent Transition Analysis (PROC LCA). University Park: The Methodology Center, Penn State. 2015. https://doi.org/10.26207/61ff-0k88

Lanza ST, Dziak JJ, Huang L, Wagner AT, Collins LM. Proc LCA & Proc LTA users' guide (Version 1.3.2). University Park: The Methodology Center, Penn State. 2015. Available from methodology.psu.edu. Accessed September, 2023.

Austin PC. An Introduction to Propensity Score Methods for Reducing the Effects of Confounding in Observational Studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399-424.

Stensrud MJ, Hernan MA. Why Test for Proportional Hazards? JAMA. 2020;323(14):1401-2.

McCaffrey DF, Griffin BA, Almirall D, Slaughter ME, Ramchand R, Burgette LF. A tutorial on propensity score estimation for multiple treatments using generalized boosted models. Stat Med. 2013;32(19):3388-414.

McCaffrey DF, Ridgeway G, Morral AR. Propensity score estimation with boosted regression for evaluating causal effects in observational studies. Psychol Methods. 2004;9(4):403-25.

McCaffrey DF, Burgette LF, Griffin BA, Martin C, Ridgeway G. Toolkit for Weighting and Analysis of Nonequivalent Groups A Tutorial for the TWANG SAS Macros. RAND Corporation. 2014. https://doi.org/10.7249/TL136

Collins PH. Intersectionality's Definitional Dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology. 2015;41(1):1-20.

Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1267-73.

Castillo DC, Ramsey NL, Yu SS, Ricks M, Courville AB, Sumner AE. Inconsistent Access to Food and Cardiometabolic Disease: The Effect of Food Insecurity. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2012;6(3):245-50.

Cutts DB, Meyers AF, Black MM, et al. US Housing insecurity and the health of very young children. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(8):1508-14.

Lebrun-Harris LA, Baggett TP, Jenkins DM, et al. Health status and health care experiences among homeless patients in federally supported health centers: findings from the 2009 patient survey. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(3):992-1017.

Fraze TK, Brewster AL, Lewis VA, Beidler LB, Murray GF, Colla CH. Prevalence of Screening for Food Insecurity, Housing Instability, Utility Needs, Transportation Needs, and Interpersonal Violence by US Physician Practices and Hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e1911514.

Lothian K, Philp I. Maintaining the dignity and autonomy of older people in the healthcare setting. BMJ. 2001;322(7287):668-70.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the clinicians and program staff for their support on the successful implementation of the social needs screening initiative. This study was presented at the International Society for Quality of Life Research 30th Annual Conference in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, 18-21 October, 2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Bates reported receiving a grant from IBM Watson and personal fees from FeelBetter, CORE, NORC, Kaiser Permanente, Early Sense, AESOP, Statista, and having equity in Clew, MDClone, ValeraHealth, FeelBetter, and Guided Clinical Solutions outside the submitted work; additionally, Dr. Bates received honoraria from Industrial Technology Research Institute (Taiwan), Vanderbilt University, and University of Utah; and finally, Dr. Bates has a patent for PHC-028654 on intraoperative clinical decision support. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, C., Kaur, M.N., Malapati, S.H. et al. Patterns of Social Needs Predict Quality-of-Life and Healthcare Utilization Outcomes in Patients from a Large Hospital System. J GEN INTERN MED (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08788-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-08788-6