Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic encouraged telemedicine expansion. Research regarding follow-up healthcare utilization and primary care (PC) telemedicine is lacking.

Objective

To evaluate whether healthcare utilization differed across PC populations using telemedicine.

Design

Retrospective observational cohort study using administrative data from veterans with minimally one PC visit before the COVID-19 pandemic (March 1, 2019–February 28, 2020) and after in-person restrictions were lifted (October 1, 2020–September 30, 2021).

Participants

All veterans receiving VHA PC services during study period.

Main Measures

Veterans’ exposure to telemedicine was categorized as (1) in-person only, (2) telephone telemedicine (≥ 1 telephone visit with or without in-person visits), or (3) video telemedicine (≥ 1 video visit with or without telephone and/or in-person visits). Healthcare utilization 7 days after index PC visit were compared. Generalized estimating equations estimated odds ratios for telephone or video telemedicine versus in-person only use adjusted for patient characteristics (e.g., age, gender, race, residential rurality, ethnicity), area deprivation index, comorbidity risk, and intermediate PC visits within the follow-up window.

Key Results

Over the 2-year study, 3.4 million veterans had 12.9 million PC visits, where 1.7 million (50.7%), 1.0 million (30.3%), and 649,936 (19.0%) veterans were categorized as in-person only, telephone telemedicine, or video telemedicine. Compared to in-person only users, video telemedicine users experienced higher rates per 1000 patients of emergent care (15.1 vs 11.2; p < 0.001) and inpatient admissions (4.2 vs 3.3; p < 0.001). In adjusted analyses, video versus in-person only users experienced greater odds of emergent care (OR [95% CI]:1.18 [1.16, 1.19]) inpatient (OR [95% CI]: 1.29 [1.25, 1.32]), and ambulatory care sensitive condition admission (OR [95% CI]: 1.30 [1.27, 1.34]).

Conclusions

Telemedicine potentially in combination with in-person care was associated with higher follow-up healthcare utilization rates compared to in-person only PC. Factors contributing to utilization differences between groups need further evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Telemedicine expanded rapidly during the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure patients received care in the safest possible setting.1, 2 Within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), primary care (PC) telemedicine is delivered by telephone or video. While patient-level barriers exist to adopt telemedicine including older age, lower income and education, as well as rural residence,3, 4 the VHA has provided qualified veterans with Internet-enabled devices and negotiated with telecommunication companies to provide free unlimited data for VHA video visits.5,6,7 As the pandemic has receded, telemedicine continues to play a role in patient care.

VHA was an early telemedicine adopter with programs focused on increasing access to primary and subspecialty care.9,10,11,12,13 As pandemic restrictions continued, VHA telemedicine surged.2, 8 In specific populations, such as patients with type 2 diabetes, heart failure, or COPD, there is evidence that home telehealth programs, using remote monitoring tools (blood pressure cuffs, pulse oximeters, etc.), can lead to decreased hospitalizations and ED visits.14,15,16 However, there is a lack of research regarding follow-up healthcare utilization following PC telemedicine, including subsequent visits to PC, emergent care (either urgent care or the emergency department), and inpatient and ambulatory care sensitive condition (ACSC) admissions. Prior studies yielded conflicting evidence with some supporting that telemedicine initiation leads to more follow-up appointments17 while others showed no less utilization and fewer hospitalizations.18, 19 Though patients and providers are generally satisfied telemedicine,20, 21 if such care increases downstream healthcare utilization, patients may be burdened by increased costs and care delays.

The study objective was to evaluate whether follow-up healthcare utilization differed across PC populations using telemedicine (i.e., video and telephone) compared to in-person. We hypothesized patients would increase PC telemedicine use after pandemic onset, and those using telemedicine would have higher overall PC visit rates. We additionally hypothesized that subsequent healthcare system use (i.e., emergent care, inpatient, or ACSC admissions) within 7 days of an index PC visit would be comparable to those using only in-person PC visits. This research can provide insights into how delivery method may impact downstream healthcare.

METHODS

Study Design

This is a retrospective observational cohort study of PC VHA outpatient visits before the COVID-19 pandemic (March 1, 2019–February 28, 2020) and after the re-opening of VHA medical centers to in-person visits (October 1, 2020–September 30, 2021). Outpatient visits between March 1, 2020, through September 30, 2020, were excluded, because in-person restrictions dramatically decreased overall healthcare utilization and necessitated telemedicine use. VHA facilities lifted restrictions at varying times during the pandemic. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline22and was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board and the Iowa City VA Healthcare System Research and Development Committee. It was conducted without direct patient contact using data routinely collected in the electronic health record. It was deemed of minimal risk; therefore, a waiver of informed consent was obtained.

Data Sources

Data were managed in the Veterans Informatics and Computing Infrastructure, a secure integrated system which includes all VHA administrative data and electronic health records. Patient-level data, including demographics, date, and delivery method for PC visits, as well as visits to the emergency department or urgent care, was obtained from the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) outpatient domain. The date of inpatient admissions was similarly identified using the CDW inpatient domain. The 2010 Census Bureau TIGER/Line shapefile contains geographic entity codes, including census block, census block group, and census tract. These data were spatially merged with the fiscal year-specific latitude and longitude of each veteran’s home address to identify their census block-based broadband availability using the December 2019 Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Fixed Broadband data,23 their census block group-based area deprivation index (ADI),24 a ranking of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage, and their census tract-based social vulnerability index (SVI),25 a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention measure of a community’s ability to respond to a hazardous event. Residential rurality classification was obtained from the Planning Systems Support Group (PSSG).

Patient Population

We established a cohort of veterans who used outpatient VHA PC prior to the pandemic (March 1, 2019–February 28, 2020) and after the re-opening of VHA medical centers (October 1, 2020–September 30, 2021). This ensured the comparison of healthcare utilization among the same group of veterans. PC encounters were categorized using stop codes, a pair of proprietary three-digit codes assigned to each outpatient encounter (Appendix 1). To be included, a veteran was required to have at least one PC visit, regardless of visit modality (i.e., in-person, telephone, or video) in each study period. We excluded care received at residential rehabilitation centers, nursing homes, or domiciliary.

Telemedicine Use

Our primary exposure was PC telemedicine (i.e., telephone or video) use. An index visit was the first PC visit within the study period, with each subsequent index visit occurring at least 7 days later. Index visits were not restricted by visit modality. Within the 7-day follow-up period, we assessed the number of days on which a PC visit occurred, categorized by visit modality (e.g., in-person, telephone, or video). Veterans were categorized into three mutually exclusive modality groups using index and intermediate PC visits throughout the study period overall as (1) in-person only, (2) telephone telemedicine (≥ 1 telephone visit with or without in-person visits), or (3) video telemedicine (≥ 1 video visit with or without telephone and/or in-person visits).

Outcomes

We studied three outcomes in the 7 days following an index PC visit: (1) emergent care (i.e., emergency department or urgent care visits), (2) any inpatient admission, and (3) any ACSC admission. Conditions included as ACSCs were community-acquired pneumonia, urinary tract infections, long- and short-term diabetes complications, lower-extremity amputation among diabetic patients, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma in older adults, heart failure, hypertension, and admission for asthma among young adults with diabetes.

Covariates

Patient demographics included age, sex, race, ethnicity, broadband availability, ADI, and SVI. Residential rurality was identified using the geocoded location of the patient’s home via Rural Urban Commuting Area codes and dichotomized into urban and rural (i.e., rural, highly rural, and insular categories).26 Race and ethnicity were self-reported. Race was categorized as American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Black/African American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, White, or Missing. Ethnicity was reported as being Hispanic, Not Hispanic, or Missing. Broadband availability was categorized according to download and upload speeds as inadequate (download ≤ 25 Mbps; upload ≤ 3 Mbps), adequate (download ≥ 25 Mbps and < 100 Mbps; upload ≥ 5 Mbps and < 100 Mbps), or optimal (download and upload ≥ 100Mbps). A minimum of 25 Mbps download and 3 Mbps upload are recommended for video telemedicine. We also calculated a comorbidity score based on the previous year using the methodology described by Quan et al. (2011), with a modification to allow for two outpatient diagnoses, as well as a single inpatient diagnosis.

Statistical Analyses

Demographic and healthcare utilization rates were compared to the in-person modality group (i.e., referent category) using chi-square or t-tests. Generalized estimating equations evaluated the difference in hospital utilization and PC visit modality group. The dependent binary variable indicated ever use of emergent care visit, any inpatient admission, or any ACSCs admissions, respectively, within 7 days of index PC visit. Independent variables included a binary indicator for study period (i.e., pre-pandemic vs. after in-person restrictions were lifted), a categorical variable for visit modality group, and their interaction. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are reported for a model with and without the interaction term. Both models adjusted for patient characteristics and the number of intermediate PC visits within the 7-day follow-up window. All logistic regressions used the binomial model structure with a logit link function, an independent error structure, and standard errors clustered at the veteran level. All hypothesis tests were two-sided with an a priori 0.05 level of significance.

Sensitivity Analyses

Similar analyses considered a variety of follow-up windows from index visit (e.g., 3, 14, and 28 days), as well as the exclusion of any PC visit with a COVID-19 diagnosis.

The authors had full access to and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data. All analyses were conducted using SAS® statistical software version 9.2 (Cary, NC) and SQL Server Management, version 18.8.

RESULTS

During the study, 3,420,034 unique veterans obtained PC at 855 PC clinics of whom 90.7% were male, 73.1% White, and 64.2% urban-residing, with a mean age of 61.7 (SD = 15.3) years (Table 1). Among the study cohort, 50.7% used only in-person care, 30.3% experienced ≥ 1 telephone visit, and 19.0% used ≥ 1 video visit. Veterans using some video versus only in-person care were younger (mean [SD], 56.5 [15.6] vs. 63.1 [15.0] years; p < 0.001), and more likely to be Black (23.7% vs. 16.0%; p < 0.001), female (15.0% vs. 8.1%; p < 0.001), and urban-residing (76.0% vs. 61.0%; p < 0.001) with more optimal broadband availability (40.8% vs. 32.2%; p < 0.001). The telephone telemedicine and in-person only groups were demographically similar, despite small, statistically significant differences.

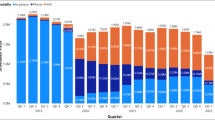

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 91.1% of veterans visited PC only in-person (N = 3,115,603) whereas 283,295 veterans experienced ≥ 1 telephone visit (8.3%), and 21,136 experienced ≥ 1 video visit (0.6%) (Fig. 1). However, after in-person visit restrictions were lifted, 1,381,992 (44.3%) veterans who had only used in-person visits pre-COVID experienced a PC visit by telephone (23.7%) or video (16.7%). Overall healthcare utilization rates over time among video or telephone users were greater than for those using only in-person visits (Fig. 2).

Number of veterans in each primary care visit modality group before the COVID-19 pandemic and after VA Medical Centers re-opened. *The pre-COVID-19 period is March 1, 2019–February 28, 2020. †The period during the COVID-19 pandemic where in-person visits were restricted is March 1, 2020–September 30, 2020. ‡The period during the COVID-19 pandemic after in-person visit restrictions were lifted is October 1, 2020–September 30, 2021.

When considering healthcare utilization within 7 days of an index visit by modality group, video versus in-person only users experienced more PC visit days (mean [SD], 4.9 [2.8] vs 3.5 [2.4]; p < 0.001) and higher rates per 1000 veterans of emergent care visits (mean [SD]: 15.1 [63.0] vs 11.2 [60.8]; p < 0.001), inpatient admissions (mean [SD]: 4.2 [32.3] vs 3.3 [32.1]; p < 0.001), and ACSC admissions (mean [SD]: 2.7 [22.9] vs 2.3 [24.2]; p < 0.001) (Table 2). Similar rates were reported for the telephone telemedicine versus in-person only group. Similar results were obtained using a 28-day follow-up window from index visit.

In adjusted analyses, veterans using video versus exclusively in-person visits pre-pandemic displayed higher odds of emergent care visits (OR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.16–1.19), inpatient admission (OR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.25–1.32), and ACSC admissions (OR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.27–1.34) (Table 3); odds remained statistically significantly higher among telephone versus in-person only groups, though to a lesser degree. Full model output is provided in Appendix 2. Among in-person only users, the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with a decrease in the odds of emergent care (OR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.90–0.92) and inpatient admission (OR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.95–0.98), but increased odds of ACSC (OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 1.02–1.06). Finally, the association of being in the video versus in-person only group modified by the COVID-19 pandemic increased the odds of emergent care (OR = 1.08, 95% CI = 1.06–1.10), inpatient admissions (OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.20–1.28), and ACSC admission (OR = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.28–1.38); similar but smaller differences were noted among telephone versus in-person only groups. The full interaction model is provided in Appendix 3. Results using a 28-day follow-up window are reported in Table 4 with similar conclusions. Results were also similar when visits with a COVID-19 diagnosis were excluded (Appendix 4).

DISCUSSION

The COVID-19 pandemic altered how VHA healthcare was delivered nationwide. However, as restrictions receded, telemedicine has remained an important delivery modality. In this study, we examined whether follow-up healthcare utilization differed between veterans receiving PC exclusively in-person or with at least one telephone or video visit. In this study we found (1) the number of veterans receiving PC in a combination of modalities has substantially increased, and (2) those using at least some video telemedicine tend to be younger, female, and urban-residing, but (3) have higher adjusted odds of experiencing emergent visits, inpatient admissions, or ACSC admissions within 7 days of an index PC visit. As telemedicine use, both via telephone and video, continues to be a routine part of care, our findings highlight the importance of understanding not only who is using telemedicine, but how such use works in conjunction with in-person visits and the subsequent effect on downstream care.

While telemedicine was available before the pandemic,27,28,29 it rapidly expanded at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.30,31,32 Overall, the ability to access care in multiple ways has the potential to improve access, especially among women and younger populations3, 4 who may feel uncomfortable receiving care in-person, require childcare, or lack the ability to take time off work. For many, especially those living in rural or underserved areas, the time and travel savings are a significant benefit despite growing literature about inequitable access to broadband in rural locations.33 However, if telemedicine use is related to further downstream utilization, it might not save the patient time or money and could cost healthcare systems more.

We found video telemedicine users had significantly more hospital utilization following a PC visit. This is contrary to previous studies indicating more readily available PC or urgent care access (in-person or telemedicine) could potentially reduce use of emergency healthcare resources.34,35,36 However, patients participating in the study by Huang et al. could self-select between video and telephone visits when in-person was only available after either modality was first used. In this setting, non-tech savvy patients could choose phone to facilitate an in-person visit, which could improve the outcomes related to a video visit. Further, with the increase in subsequent healthcare utilization noted in our study, it is possible a system already exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic may see additional system-wide strains in the forms of staff, supply, and space shortages.37 This strain was especially apparent at pandemic start; however, ongoing shortages of nursing staff, medications, and other supplies38,39,40 continue to impact healthcare.

It is not yet clear why patients who utilized telemedicine had significantly higher odds of emergent or inpatient care, and ACSC admissions even after adjusting for patient characteristics, including comorbidity levels. Because we categorized patients based on their overall telemedicine use across both study periods, it is important to note this increased use does not imply care received over the phone or via video was inappropriate. Instead, we hypothesize telemedicine users may choose to use this modality multiple reasons. For example, both telemedicine groups had a higher number of intermediate PC visit days, representing increased PC use in between index visits, and yet showed similar average comorbidity scores. It is likely some video telemedicine patients requiring emergent or inpatient care may generally use the healthcare system more and thus take advantage of multiple modalities, while others may use this modality because they are healthy and do not feel an in-person visit is needed or find a video visit more convenient. It is also possible that patients initiated or agreed to try telemedicine for the first time because of an emerging acute need. This may have been especially true during so-called COVID waves, when patients were more likely to seek telemedicine visits to avoid the risk of in-person appointments. Subsequent PC visits would be expected to be higher if telemedicine cannot resolve the issue or if it determined a physical exam or procedure, or other follow-up is required. In this context, telemedicine may act as an intermediate facilitator or triaging agent for important and life-saving care that may otherwise have been delayed or overlooked. This may be especially true for patients who want to receive care within the VHA versus obtaining VHA-funded care in their community. Future work should consider the factors that lead a patient to choose telemedicine, how telemedicine and in-person visits work in conjunction with one another, and the effect of facility-level factors influencing patient flow from PC visit to emergent care or inpatient admission and telemedicine utilization patterns.

This research has limitations. First, our results amongst the veteran population may not be generalizable to the overall US adult population. However, the size of this nationwide study remains a significant strength. Second, we were unable to account for any healthcare utilization obtained in community locations. This may be particularly relevant for veterans who have private insurance or may live too far away from VHA services to quickly obtain emergency services at a VHA medical center. Selection bias is also a concern as telemedicine users may be more connected to their VHA healthcare team and thus more likely to seek care within the VHA system. Finally, we did not determine if the use of emergent care or inpatient services was related to the chief complaint of the PC index visit. However, it remains likely that follow-up healthcare in emergent or inpatient settings is related to acute exacerbations of chronic conditions addressed at nearly every PC visit including diabetes, hypertension, and heart failure. Reviewing both index visits and follow-up healthcare complaints could provide insight into whether appropriate care was missed during the index visit leading to further utilization later.

The COVID-19 pandemic considerably increased telemedicine use. Identifying and studying veterans with a measurable difference in healthcare utilization can provide insights into how the method of care delivery may impact PC access and follow-up healthcare utilization.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed are not publicly available due to VHA privacy and confidentiality requirements.

References

Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually Perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. Apr 30 2020;382(18):1679-1681. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2003539

Baum A, Kaboli PJ, Schwartz MD. Reduced In-Person and Increased Telehealth Outpatient Visits During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Intern Med. Jan 2021;174(1):129-131. doi:https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-3026

Lin CC, Dievler A, Robbins C, Sripipatana A, Quinn M, Nair S. Telehealth In Health Centers: Key Adoption Factors, Barriers, And Opportunities. Health Aff (Millwood). Dec 2018;37(12):1967-1974. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05125

Nguyen OT, Watson AK, Motwani K, et al. Patient-Level Factors Associated with Utilization of Telemedicine Services from a Free Clinic During COVID-19. Telemed J E Health. Apr 2022;28(4):526-534. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2021.0102

U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. Bridging the Digital Divide. Accessed 9/15/2021, https://telehealth.va.gov/digital-divide

VA’s telehealth system grows as Veterans have access to unlimited data while using VA Video Connect. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5426

Zulman DM, Wong EP, Slightam C, et al. Making connections: nationwide implementation of video telehealth tablets to address access barriers in veterans. JAMIA Open. Oct 2019;2(3):323-329. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jamiaopen/ooz024

Der-Martirosian C, Wyte-Lake T, Balut M, et al. Implementation of Telehealth Services at the US Department of Veterans Affairs During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(9):e29429. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/29429

Darkins A. The Growth of Telehealth Services in the Veterans Health Administration Between 1994 and 2014: A Study in the Diffusion of Innovation. Telemedicine and e-Health. 9/3/2014 2014;20(9)doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2014.0143

Heyworth L, Kirsh S, Zulman D, Ferguson JM, Kizer KW. Expanding access through virtual care: The VA’s early experience with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;1(4)

Jiang CY, El-Kouri NT, Elliot D, et al. Telehealth for Cancer Care in Veterans: Opportunities and Challenges Revealed by COVID. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;1:22-29.

Rosen CS, Morland LA, Glassman LH, et al. Virtual mental health care in the Veterans Health Administration's immediate response to coronavirus disease-19. Am Psychol. Jan 2021;76(1):26-38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000751

Der-Martirosian C, Chu K, Dobalian A. Use of Telehealth to Improve Access to Care at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs during the 2017 Atlantic Hurricane Season. Article in Press. Disaster Med Public Health Preparedness. 2020:1-13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.88

Barnett TE, Chumbler NR, Vogel WB, Beyth RJ, Qin H, Kobb R. The effectiveness of a care coordination home telehealth program for veterans with diabetes mellitus: a 2-year follow-up. American Journal of Managed Care. 2006;12(8):467.

Guzman-Clark J, Wakefield BJ, Farmer MM, et al. Adherence to the Use of Home Telehealth Technologies and Emergency Room Visits in Veterans with Heart Failure. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2021;27(9):1003-1010.

Bhatt SP, Patel SB, Anderson EM, et al. Video telehealth pulmonary rehabilitation intervention in COPD reduces 30-day readmissions. Conference Abstract. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(9)

Liu X, Goldenthal S, Li M, Nassiri S, Steppe E, Ellimoottil C. Comparison of telemedicine versus in-person visits on impact of downstream utilization of care. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2021;27(10):1099-1104.

Nord G, Rising KL, Band RA, Carr BG, Hollander JE. On-demand synchronous audio video telemedicine visits are cost effective. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2019;37(5):890-894.

Peters GM, Kooij L, Lenferink A, Van Harten WH, Doggen CJ. The effect of telehealth on hospital services use: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of medical internet research. 2021;23(9):e25195.

Kintzle S, Rivas WA, Castro. CA. Satisfaction of the Use of Telehealth and Access to Care for Veterans During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2022:706–711. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2021.0262

Vosburg RR, K. Telemedicine in Primary Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Provider and Patient Satisfaction Examined. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2022;

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. Apr 2008;61(4):344-9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

Commission FC. Data from: Form 477 Broadband Deployment Data - December 2019 (version 1). 2019. Deposited April 9, 2021.

University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. 2015 Area Deprivation Index v2.0. Accessed February 4, 2021, https://www.neighborhoodatlas.medicine.wisc.edu/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/ Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry/ Geospatial Research, Analysis, and Services Program,. Data from: CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index 2018 Database US.

University of Washington Rural Health Research Center and USDA Economic Research Service (ERS). Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. Accessed December 13, 2018, http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-uses.php

Girard P. Military and VA telemedicine systems for patients with traumatic brain injury. Article. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development. 2007/12/2007;44:.

Moreau JL, Cordasco KM, Young AS, et al. The Use of Telemental Health to Meet the Mental Health Needs of Women Using Department of Veterans Affairs Services. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(2):181-187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2017.12.005

Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of Telehealth. The New England journal of medicine. 2016;375(2):154-161. doi:https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1601705

Doraiswamy S, Abraham A, Mamtani R, Cheema S. Use of Telehealth During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res. Dec 1 2020;22(12):e24087. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/24087

Ferguson JM, Jacobs J, Yefimova M, Greene L, Heyworth L, Zulman DM. Virtual care expansion in the Veterans Health Administration during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical services and patient characteristics associated with utilization. J Am Med Informa Assoc. 2021 2020; 28(3):453–462.

Zeng B, Rivadeneira NA, Wen A, Sarkar U, Khoong EC. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Internet Use and the Use of Digital Health Tools: Secondary Analysis of the 2020 Health Information National Trends Survey. J Med Internet Res. Sep 19 2022;24(9):e35828. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/35828

Cortelyou-Ward K, Atkins DN, Noblin A, Rotarius T, White P, Carey C. Navigating the Digital Divide: Barriers to Telehealth in Rural Areas. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2020;31(4):1546-1556.

Yoon J, Cordasco KM, Chow A, Rubenstein LV. The Relationship between Same-Day Access and Continuity in Primary Care and Emergency Department Visits. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0135274. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135274

Wray CM, Junge M, Keyhani S, Smith JE. Assessment of a multi-center tele-urgent care program to decrease emergency department referral rates in the Veterans Health Administration. J Telemed Telecare. 2021:1357633x211024843. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633x211024843

Huang J, Gopalan A, Muelly E, et al. Primary care video and telephone telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: treatment and follow-up health care utilization. Am J Manag Care. 2023;29(1):e13-e17. doi:https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2023.89307

Myers LC, Liu VX. The COVID-19 Pandemic Strikes Again and Again and Again. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5(3):e221760-e221760. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.1760

Dyer O. Covid-19: Ontario hospitals close wards as nursing shortage bites. BMJ. 2022;378:o1917. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o1917

Lopez V, Anderson J, West S, Cleary M. Does the COVID-19 Pandemic Further Impact Nursing Shortages? Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2022/03/04 2022;43(3):293-295. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2021.1977875

Choo EK, Rajkumar SV. Medication Shortages During the COVID-19 Crisis: What We Must Do. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(6):1112-1115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.001

Funding

This material is based upon work supported (or supported in part) by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Rural Health, Veterans Rural Health Resource Center–Iowa City (03806), and the Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Service through the Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE) Center (CIN 13–412), as well as the VHA Primary Care Analytics Team (PCAT), funded by the VHA Office of Primary Care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

None.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest:

This manuscript is not under review elsewhere and there is no prior publication of manuscript contents. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. The authors report no conflict of interest regarding this study.

Disclaimer:

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations

This manuscript is not under review elsewhere and there is no prior publication of manuscript contents. The contents of this manuscript was presented as a poster at the Society of General Internal Medicine Meeting in May 2023.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Shea, A.M.J., Mulligan, K., Carlson, P. et al. Healthcare Utilization Differences Among Primary Care Patients Using Telemedicine in the Veterans Health Administration: a Retrospective Cohort Study. J GEN INTERN MED 39 (Suppl 1), 109–117 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08472-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08472-1