Abstract

Background

The unprecedented use of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic provided an opportunity to examine its uptake among individuals with limited English proficiency (LEP).

Objective

To assess telemedicine use among nonelderly adults with LEP and the association between use of telehealth and emergency department (ED) and hospital visits.

Design

Cross-sectional study using the National Health Interview Survey (July 2020–December 2021)

Participants

Adults (18–64 years), with LEP (N=1488) or English proficiency (EP) (N=25,873)

Main Measures

Telemedicine, ED visits, and hospital visits in the past 12 months. We used multivariate logistic regression to assess (1) the association of English proficiency on having telemedicine visits; and (2) the association of English proficiency and telemedicine visits on having ED and hospital visits.

Key Results

Between July 2020 and December 2021, 22% of adults with LEP had a telemedicine visit compared to 35% of adults with EP. After controlling for predisposing, enabling, and need factors, adults with LEP had 20% lower odds of having a telemedicine visit than adults with EP (p=0.02). While English proficiency was not associated with ED or hospital visits during this time, adults with telemedicine visits had significantly greater odds of having any ED (aOR: 1.80, p<0.001) and hospital visits (aOR: 2.03, p<0.001) in the past 12 months.

Conclusions

While telemedicine use increased overall during the COVID-19 pandemic, its use remained much less likely among adults with LEP. Interventions targeting structural barriers are needed to address disparities in access to telemedicine. More research is needed to understand the relationship between English proficiency, telemedicine visits, and downstream ED and hospital visits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

In the USA, over 25 million people have limited English proficiency (LEP), or speak English “less than very well.”1 LEP is associated with low English literacy overall and low health literacy, increasing the risk of poorer access and use of healthcare, including being less likely to have doctor’s visits and more likely to have preventable emergency department (ED) visits.2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 During the pandemic, more than 50% of adults with LEP reported delayed or forgone healthcare, compared with less than 20% prior to the pandemic, likely reflecting significant barriers to access worsened by the pandemic.9,10

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the digital transformation of healthcare by inducing clinicians, practices, and healthcare systems to shift much of their clinical care from in-person to virtual telemedicine visits, starting in March 2020. Several studies have shown the growth of telemedicine among patients and healthcare providers since the start of the pandemic.11,12,13,14 At its peak in April 2020, telemedicine constituted 42% of ambulatory visits.13

Many studies have found disparities in telemedicine use among underserved and vulnerable populations.12,15,16,17,18,19,20 Adults with LEP are particularly vulnerable to being left behind by the digital divide and telemedicine because structural barriers related to technology use (e.g., access to internet-connected devices) and language barriers often compound one another.15,21 Since the onset of the pandemic, studies of specific healthcare systems found that LEP patients were 16–37% less likely to have a telemedicine visit than EP patients.17,18

The impact of access to telemedicine on the use of other healthcare services, including ED visits and hospital visits, is unclear. Findings from the limited literature examining the relationship between telemedicine and other healthcare services have been mixed.19,22,23,24,25,26 To our knowledge, no national studies have examined the relationships between English proficiency, telemedicine use, and ED and hospital visits.

Given the dramatic increase in the use of telemedicine in healthcare, there is a pressing need to understand telemedicine use among adults with LEP. Using a nationally representative sample, our objective was to assess telemedicine use among nonelderly adults with LEP after the pandemic onset (July 2020 to December 2021). We aimed to examine (1) the use of telemedicine among adults with LEP compared to adults with English proficiency (EP) and (2) whether having telemedicine visits modified the relationship between English proficiency and ED and hospital visits. We hypothesized that adults with LEP were less likely than adults with EP to have telemedicine visits, and that having telemedicine visits would modify the relationship between English proficiency and ED and hospital visits. Understanding the uptake of technology among adults with LEP is needed to ensure equitable access to healthcare services.

METHODS

Data and Sample

This study combined data from the 2020 and 2021 National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS), a nationally representative, cross-sectional household survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized US population.27,28 Between July 2020 and April 2021, interviews were first conducted over the telephone, with in-person follow-up to complete interviews.29,30 In May 2021, interviews returned to their standard process (in-person with a telephone follow-up).30 The final adult response rate was 48.9% for 2020 and 50.9% in 2021.29,30 After excluding respondents with missing values (1.1% of the sample), our analytic sample included nonelderly, White, Hispanic, and Asian adult respondents interviewed between July 2020 and December 2021 (n=27,361). Less than 0.4% of Black and Other race respondents identified as LEP; these groups were excluded to focus the analyses on the healthcare utilization of the LEP population. This study used publicly available, de-identified data and was deemed to not be human subject research by the Advocate Aurora Health Institutional Review Board.

Measures

We assessed types of healthcare utilization during the past 12 months based on self-report measures: having any telemedicine visits, any ED visits, and any hospital visits. All outcomes were dichotomous. To measure telemedicine visits, respondents were asked whether they “had an appointment with a doctor, nurse, or other health professional by video or by phone.”29 Other utilization outcomes were constructed from a question asking respondents how many times they had visited the ED (any ED visits), and if they had been hospitalized overnight (any hospital visits). Full question texts can be found in Appendix A.

The primary independent variable was English proficiency. Respondents were categorized as LEP if their interview was conducted in Spanish, both English and Spanish, or some other language; interviews with EP respondents were conducted in English only. Following the Andersen model to account for factors that may affect healthcare utilization,31 we controlled for predisposing, enabling, and need factors. Predisposing factors included age (18–29, 30–29, 40–49, 50–64 years), sex (male, female), and race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian). Need factors included health status (excellent/very good/good, fair/poor), disability (yes, no), and any 1 of 6 common chronic conditions (arthritis, cancer, congestive heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol). Enabling factors included education (some college or higher, high school diploma, less than high school diploma), family income (<100% of federal poverty level [FPL], 100-199% FPL, ≥200% FPL), insurance coverage (private, public/other, uninsured), usual place of care (yes, no), and place of residence (metropolitan or nonmetropolitan).

Statistical Analysis

We used the χ2 test to compare differences in predisposing, enabling, and need factors by English proficiency. We also used the χ2 test to examine differences in telemedicine visits between and across survey quarters. We then conducted two analyses using multivariate logistic regression models.

The first analysis examined the association between English proficiency and having a telemedicine visit, and whether the relationship changed with the systematic inclusion of predisposing, enabling, and need factors. Model 1 included only predisposing factors, model 2 added need factors, and model 3 further added enabling factors.

The second analysis assessed the association between English proficiency and having any ED visits and any hospital visits. We first estimated models controlling for predisposing, need, and enabling factors. We then re-estimated the models adding telemedicine visits as an independent variable. In a third specification, we added an interaction term to assess whether having telemedicine visits moderated the association between English proficiency and other types of healthcare utilization. Lastly, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess whether the interaction between English proficiency and utilization differed by Hispanic ethnicity and Asian race, compared to White race.

All analyses were conducted using Stata version 17.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) and used statistical methods to account for the complex survey design (i.e., weighting). Two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

This study included 27,361 nonelderly, adult respondents, representing over 163 million people nationally; 7.5% were identified as LEP. Table 1 shows descriptive characteristics of English proficiency. Adults with LEP were significantly more likely to be middle-aged and Hispanic, have worse health, not have a high school diploma, have a family income below <200% FPL, have public insurance or be uninsured, live in a metropolitan area, and not have a usual place of care. Similar percentages of adults with LEP and EP had a disability and at least one chronic condition.

Rates of Telemedicine Visits and Other Healthcare Utilization

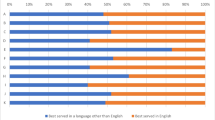

Figure 1 presents the rates of healthcare utilization by English proficiency reported from July 2020 to December 2021. Compared to adults with EP, in the past 12 months, a significantly smaller percentage of adults with LEP reported having any telemedicine visits (22% vs. 35%, p<0.001). In contrast, compared to adults with EP, a larger percentage of adults with LEP reported having any ED visits (19% vs. 15%, p=0.01), while a similar percentage reported having any hospital visits (7% vs. 6%, p>0.05).

Healthcare utilization in the past 12 months among nonelderly US adults, by English proficiency, National Health Interview Survey, July 2020–December 2021. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Data source: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, July 2020–December 2021.

Figure 2 presents rates of telemedicine visits in the past year by English proficiency reported in each interview quarter. The percentage of adults with EP who had a telemedicine visit during the past year increased by 18% during the period (30% in quarter 3 of 2021 to 35% in quarter 4 of 2022). In contrast, the percentage of adults with LEP who had a telemedicine visit remained virtually constant, increasing from 21.6 to 21.9%, over the same period. In each survey quarter throughout the period, compared to adults with EP, a significantly smaller percentage of adults with LEP reported having telemedicine visits in the past 12 months (all p<0.05).

Factors Associated with Telemedicine Visits

Table 2 shows the association of English proficiency on telemedicine visits, controlling for predisposing, need, and enabling factors. Controlling for predisposing factors only (model 1), adults with LEP had much lower odds of having a telemedicine visit (aOR: 0.56, p<0.001). After controlling for need as well as predisposing factors (model 2), the negative relationship between LEP and telemedicine visits remained large and virtually unchanged (aOR: 0.52, p<0.001). Finally, in model 3, fully adjusting for predisposing, need, and enabling factors, the association between LEP and telemedicine is attenuated but continues to be statistically significant (aOR: 0.80, p=0.02).

In the full model (model 3), among the predisposing factors, the negative association of Asian race on the odds of having a telemedicine visit remained (aOR: 0.75, p<0.001). However, Hispanic ethnicity was no longer a significant association. In relation to age, only being in the oldest group (50–64 years), compared with being 18–29 years, significantly lowered the odds, while being female increased the odds. All three need factors were associated with increased odds of having a telehealth visit: being in fair/poor health, having a disability, and having ≥1 chronic condition(s). Among the enabling factors, both education and family income followed a gradient; lower education levels and income were associated with lower odds of a telemedicine visit. Compared to being privately insured, public or other insurance increased the odds, while being uninsured lowered the odds. Not having a usual place of care and living in nonmetropolitan areas were associated with lower odds of a telemedicine visit.

Factors Associated with ED and Hospital Visits

We tested whether English proficiency and telemedicine were associated with having any ED and hospital visits. We found that limited English proficiency was not significantly associated with either type of visit. Having any telemedicine visit did not modify the effect (Wald’s χ2 test of joint significance, both p>0.05). However, having a telemedicine visit was independently associated with significantly greater odds of having an ED (aOR: 1.80, p<0.001) and a hospital visit (aOR: 2.03, p<0.001) (Table 3). Full models are available in Appendix B.

Sensitivity Analyses

We tested the interaction between English proficiency and race and ethnicity in the ED and hospital visit models. The interactions were not statistically significant (Wald’s χ2 test of joint significance, both p>0.05), and we concluded the effect of English proficiency on healthcare utilization was not modified by race and ethnicity.

DISCUSSION

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a large portion of US adults used telemedicine to access healthcare. Using a nationally representative sample of nonelderly adults, we found that between July 2020 and December 2021, 22% of adults with LEP had a telemedicine visit compared to 35% of adults with EP. While these rates of telemedicine use are markedly higher than pre-pandemic rates in both groups (e.g., 5% of LEP and 12% of EP in California used telemedicine between 2015 and 2018),19 as hypothesized, this study found adults with LEP to be 20% less likely than adults with EP to have a telemedicine visit, even after accounting for predisposing, enabling, and need factors.

Prior studies examining telemedicine use in California, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey have reported similar or larger disparities in telemedicine use between LEP and EP patients, both before and after the start of the pandemic.17,18,19 Notably, in our national study, we observed that between July 2020 and December 2021, telemedicine visit rates among adults with LEP remained virtually unchanged while telemedicine visit rates increased among adults with EP. If this pattern persists, the disparity in telemedicine use between LEP and EP adults will worsen if nothing is done to mitigate it.

The disparity in telemedicine use among adults with LEP likely reflects a confluence of structural barriers to accessing telemedicine.15,32 In addition to being impacted by the digital divide, LEP adults also encounter LEP-specific barriers, including the need for medical interpreters and English-only virtual platforms and technologies.15,21,32 To improve access to telemedicine, healthcare systems need to be intentional in designing and implementing services to be accessible to all patients. Successful strategies to address disparities among LEP patients include interventions to address healthcare system barriers, such as custom building patient portals in the most frequent patient languages, using virtual platforms that do not require application download or patient portal signup, ensuring easy inclusion of interpreters in telemedicine visits, and partnering with local organizations to identify and address language and culture-specific needs.15,32 Patient-centered strategies may include outreach and education in multiple languages to help patients signup for patient portals and how to set up and conduct telemedicine visits on multiple device types.15,32

Consistent with findings from previous studies,17,18,19 we also found Asian race to be associated with a lower likelihood of telemedicine use, after controlling for English proficiency. Despite higher rates of internet use and technology adoption reported among English-speaking Asian Americans,33 our study findings concerning telemedicine use mirror early findings of lower patient portal adoption rates among Asian Americans.34 Less use of telemedicine may reflect lower overall healthcare use,35,36,37 negative experiences with the healthcare system,38 and even differences in where they seek care.39,40 Whether the difference in telemedicine use among Asian Americans can be explained by differences in preferences, experiences, or other factors is unclear and requires further investigation.

We found that adults with LEP and EP have a similar likelihood of using the ED and hospital, after adjusting for covariates, despite a larger percentage of adults with LEP having any ED visits. Also, contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find that the interaction between English proficiency and telemedicine use moderated the relationship. Previous works examining differences in ED and hospital use among adults with LEP have been mixed.8,41,42 One MEPS-based study found Hispanic LEP adults to be associated with lower rates of ED and hospital visits than both Hispanic and non-Hispanic EP adults,8 while one health system–based study found LEP adults to have higher rates of ED and hospital visits than EP adults.41,42 From our findings, we conclude that English proficiency was not associated with an excess of ED visits, though we cannot determine whether the amount of healthcare used was clinically appropriate. Coupling our findings with those of a previous study showing that a greater percentage of adults with LEP delayed or forwent healthcare during the pandemic10 cautions that the lack of difference in ED visits between adults with LEP and EP may be temporary. Continued vigilance in monitoring the level and types of healthcare utilization among adults with LEP is needed to ensure that telemedicine does not result in disparities in access and use.

While telemedicine did not moderate the relationship between English proficiency and ED and hospital visits, we found telemedicine use to be positively associated with any ED and hospital visits. The relationship between telemedicine use and other healthcare utilization has been found to vary by reason for the visit, telemedicine mode, and care setting.23,24,25,26,43 While the NHIS data does not allow us to differentiate between telemedicine modes (i.e., video, telephone), care settings, sequence, or reasons for telemedicine visits, our findings are similar to another cross-sectional study that found telemedicine use to be positively associated with ED visits.19 Given the cross-sectional nature of the data, the extent to which telemedicine use led to increases in ED and hospital visits or the reverse is unclear. On the one hand, telemedicine visits may have caused more ED visits, perhaps due to a greater prevalence of telephone visits or telemedicine visits for acute conditions during the pandemic.24,43 One claims-based study found that, compared to in-person encounters, telemedicine encounters for acute conditions were more likely to lead to follow-up ED visits while follow-up visits were similar for telemedicine encounters for chronic conditions.24 Another study of primary care visits in Northern California found ED visits to be higher after primary care telephone visits (but not video visits).43 Conversely, telemedicine visits may have facilitated healthcare access by allowing more post-discharge follow-up visits to be conducted virtually, reducing traditional barriers such as transportation issues and COVID-19-driven barriers like fears of infection.20,25,26 A study of hospitals in Pennsylvania and a study of primary care clinics in New York City both found telemedicine visits to increase follow-up primary care visits.25,26 Further research is needed to elucidate the relationship between telemedicine and downstream healthcare utilization.

The telemedicine policy landscape continues to evolve. Many of the flexibilities supporting telemedicine coverage and payment, enacted by the federal government to address the COVID public health emergency, expire at the end of 2024.44 Private payers and many states are expected to follow suit, resulting in a more limited scope and reach of telemedicine services.

On the other hand, other changes made during the pandemic suggest that telemedicine will persist as a form of healthcare delivery. Many healthcare systems made substantial investments in telehealth, including infrastructure and staff training. Additionally, many patients prefer telemedicine, particularly for routine medical care and ongoing mental health services.45 Also, while many of the federal government’s healthcare-specific investments may be ending, its continuing support for infrastructure improvements to bring high-speed internet access to both urban and rural hard-to-reach areas will expand the potential telemedicine patient population.46 Coupled with provider shortages, telemedicine may stand out as a financially advantageous avenue for organizing care delivery, namely care from providers who are fluent in languages other than English.

Our study has several limitations. First, the 2020 and 2021 NHIS did not ask respondents how well they spoke English, so we based our definition of LEP on the language in which the survey was administered. While this approach may not have accurately captured respondents’ ability to speak and understand English, interview language is a common proxy for English proficiency in the health services literature because respondents interviewing in another language have been found to commonly need healthcare language services.7,8,9,47 Second, data were obtained from patient self-report and not confirmed through medical records; some variables may be subject to recall bias.48 Finally, the recall period for utilization measures was the previous 12 months so the earlier cohorts included a period both before the February 2020 declaration of a public health emergency and during the pandemic. Despite limitations, our study confirms at a national scale, the earlier and more geographically limited findings of key disparities in telemedicine use among LEP adults. These findings support pursuing further investigation to better understand the interplay of reasons for disparities in telemedicine use.

CONCLUSIONS

Nationally, adults with LEP reported being less likely to use telemedicine than other adults during the first 1.5 years of the COVID-19 pandemic. This disparity persisted after controlling for predisposing, need, and enabling factors that can affect access. Use of telemedicine was associated with having ED and hospital visits. These findings highlight that if policymakers support the uptake of telemedicine as a viable and important avenue to care, attention needs to focus on interventions addressing access barriers based on language to ensure adults with LEP are not left behind in the digital divide.

Data Availability

Data from 2020 and 2021 were downloaded from the CDC NHIS website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/index.htm).

References

U.S. Census Bureau. 2016-2020 American community survey 5-year estimates (Table CP02). https://api.census.gov/data/2020/acs/acs5/profile. Accessed 13 Sep 2022.

Ramirez N, Shi K, Yabroff KR, Han X, Fedewa SA, Nogueira LM. Access to care among adults with limited english proficiency. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07690-3

Foiles Sifuentes AM, Robledo Cornejo M, Li NC, Castaneda-Avila MA, Tjia J, Lapane KL. The role of limited english proficiency and access to health insurance and health care in the affordable care act era. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):509-517. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2020.0057

Anderson TS, Karliner LS, Lin GA. Association of primary language and hospitalization for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Med Care. 2020;58(1):45-51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000001245

Derose KP, Baker DW. Limited english proficiency and Latinos' use of physician services. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(1):76-91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/107755870005700105

Brach C, Chevarley FM. Demographics and health care access and utilization of limited-english-proficient and english-proficient hispanics. Research Findings No. 28. 2008. http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications//rf28/rf28.pdf

Himmelstein J, Cai C, Himmelstein DU, et al. Specialty care utilization among adults with limited english proficiency. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2022;37(16):4130-4136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07477-6

Himmelstein J, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, et al. Health care spending and use among hispanic adults with and without limited english proficiency, 1999–2018. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(7):1126-1134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02510

Shi L, Lebrun LA, Tsai J. The influence of english proficiency on access to care. Ethn Health. 2009;14(6):625-42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13557850903248639

Chang E. Differences in delayed or forgone care among adults by english proficiency during the COVID-19 pandemic. presented at: APHA Annual Meeting & Expo; 2022; Boston, MA

Lucas J, Villarroel M. Telemedicine use among adults: United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief, no 445. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2022.

Rodriguez JA, Betancourt JR, Sequist TD, Ganguli I. Differences in the use of telephone and video telemedicine visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Manag Care. 2021;27(1):21-26. doi:https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2021.88573

Patel SY, Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Uscher-Pines L, Ganguli I, Barnett ML. Trends in outpatient care delivery and telemedicine during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(3):388-391. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5928

Uscher-Pines L, Sousa J, Jones M, et al. Telehealth use among safety-net organizations in California During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. 2021;325(11):1106-1107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.0282

Nouri S, Khoong EC, Lyles CR, Karliner L. Addressing equity in telemedicine for chronic disease management during the Covid-19 pandemic. NEJM Catalyst. Accessed January 19, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1056/CAT.20.0123

Patel SY, Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Uscher-Pines L, Ganguli I, Barnett ML. Variation in telemedicine use and outpatient care during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):349-358. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01786

Sachs JW, Graven P, Gold JA, Kassakian SZ. Disparities in telephone and video telehealth engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMIA Open. 2021;4(3):ooab056. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jamiaopen/ooab056

Eberly LA, Kallan MJ, Julien HM, et al. Patient Characteristics associated with telemedicine access for primary and specialty ambulatory care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(12):e2031640-e2031640. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.31640

Rodriguez JA, Saadi A, Schwamm LH, Bates DW, Samal L. Disparities in telehealth use among California patients with limited english proficiency. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(3):487-495. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00823

Reed ME, Huang J, Graetz I, et al. Patient characteristics associated with choosing a telemedicine visit vs office visit with the same primary care clinicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e205873. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5873

Payán DD, Frehn JL, Garcia L, Tierney AA, Rodriguez HP. Telemedicine implementation and use in community health centers during COVID-19: Clinic personnel and patient perspectives. SSM Qual Res Health. 2022;2:100054. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100054

Reid S, Bhatt M, Zemek R, Tse S. Virtual care in the pediatric emergency department: a new way of doing business? Cjem. 2021;23(1):80-84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-020-00048-w

Ryskina KL, Shultz K, Zhou Y, Lautenbach G, Brown RT. Older adults' access to primary care: Gender, racial, and ethnic disparities in telemedicine. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(10):2732-2740. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17354

Hatef E, Lans D, Bandeian S, Lasser EC, Goldsack J, Weiner JP. Outcomes of in-person and telehealth ambulatory encounters during COVID-19 Within a Large Commercially Insured Cohort. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e228954. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.8954

Chen K, Zhang C, Gurley A, Akkem S, Jackson H. Primary care utilization among telehealth users and non-users at a large urban public healthcare system. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0272605. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272605

Bressman E, Werner RM, Childs C, Albrecht A, Myers JS, Adusumalli S. Association of telemedicine with primary care appointment access after hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(11):2879-2881. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07321-3

National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey, 2020. Public-use data file and documentation. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm. Accessed 20 Apr 2022.

National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey, 2021. Public-use data file and documentation. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

National Center for Health Statistics. Survey Description, National Health Interview Survey, 2020. 2021. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2020/srvydesc-508.pdf. Accessed 20 Apr 2022.

National Center for Health Statistics. Survey Description, National Health Interview Survey, 2021. 2022. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2021/srvydesc-508.pdf. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1-10.

Tan-McGrory A, Schwamm LH, Kirwan C, Betancourt JR, Barreto EA. Addressing virtual care disparities for patients with limited English proficiency. Am J Manag Care. 2022;28(1):36-40. doi:https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2022.88814

Perrin A. English-speaking Asian Americans stand out for their technology use. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2016/02/18/english-speaking-asian-americans-stand-out-for-their-technology-use/. Accessed 7 Jul 2023.

Chang E, Blondon K, Lyles CR, Jordan L, Ralston JD. Racial/ethnic variation in devices used to access patient portals. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(1):e1-e8.

Kim EJ, Parker VA, Liebschutz JM, Conigliaro J, DeGeorge J, Hanchate AD. Racial and ethnic differences in healthcare utilization among medicare fee-for-service enrollees. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(12):2697-2699. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05426-4

Chen JY, Diamant A, Pourat N, Kagawa-Singer M. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of preventive services among the elderly. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(5):388-95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.006

Park S, Stimpson JP, Pintor JK, et al. The effects of the affordable care act on health care access and utilization among Asian American subgroups. Med Care. 2019;57(11):861-868. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000001202

Ngo-Metzger Q, Legedza AT Phillips RS. 2004 Asian Americans' reports of their health care experiences. Results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 19(2):111-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30143.x

Gaskin DJ, Arbelaez JJ, Brown JR, Petras H, Wagner FA, Cooper LA. Examining racial and ethnic disparities in site of usual source of care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(1):22-30.

Nguyen KH, Oh EG, Trivedi AN. Variation in usual source of care in Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Other Pacific Islander adult medicaid beneficiaries. Med Care. 16 2022;https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000001709

Njeru JW, St. Sauver JL, Jacobson DJ, et al. Emergency department and inpatient health care utilization among patients who require interpreter services. BMC Health Services Research. 2015/05/29 2015;15(1):214. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0874-4

Ngai KM, Grudzen CR, Lee R, Tong VY, Richardson LD, Fernandez A. The association between limited english proficiency and unplanned emergency department revisit within 72 Hours. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(2):213-21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.02.042

Reed M, Huang J, Graetz I, Muelly E, Millman A, Lee C. Treatment and follow-up care associated with patient-scheduled primary care telemedicine and in-person visits in a large integrated health system. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11):e2132793. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.32793

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Telehealth policy changes after the COVID-19 public health emergency. HRSA. Updated January 23, 2023. https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/policy-changes-during-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency/policy-changes-after-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency/. Accessed 8 Feb 2023.

Predmore ZS, Roth E, Breslau J, Fischer SH, Uscher-Pines L. Assessment of patient preferences for telehealth in Post–COVID-19 Pandemic Health Care. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(12):e2136405-e2136405. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.36405

National Telecommunications and Information Administration. FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration’s “Internet for All” Initiative: Bringing Affordable, Reliable High-Speed Internet to Everyone in America. 2022. https://www.commerce.gov/news/fact-sheets/2022/05/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administrations-internet-all-initiative-bringing. Accessed 13 May 2022.

Weinick RM, Krauss NA. Racial/ethnic differences in children's access to care. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(11):1771-4. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.90.11.1771

Bhandari A, Wagner T. Self-Reported utilization of health care services: improving measurement and accuracy. Medical Care Research and Review. 2006;63(2):217-235. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558705285298

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior presentations

A prior version of the findings was presented at the 2022 American Public Health Association Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, as well as the 2023 Health Care Systems Research Network Meeting, Denver, CO.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, E., Davis, T.L. & Berkman, N.D. Differences in Telemedicine, Emergency Department, and Hospital Utilization Among Nonelderly Adults with Limited English Proficiency Post-COVID-19 Pandemic: a Cross-Sectional Analysis. J GEN INTERN MED 38, 3490–3498 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08353-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08353-7