Abstract

Background

Hospitalist physician stress was exacerbated by the pandemic, yet there have been no large scale studies of contributing factors.

Objective

Assess remediable components of burnout in hospitalists.

Participants, Study Design and Measures

In this Coping with COVID study, we focused on assessment of stress factors among 1022 hospital-based clinicians surveyed between April to December 2020. We assessed variables previously associated with burnout (anxiety/depression due to COVID-19, work overload, fear of exposure or transmission, mission/purpose, childcare stress and feeling valued) on 4 point Likert scales, with results dichotomized with the top two categories meaning “present”; burnout was assessed with the Mini Z single item measure (top 3 choices = burnout). Quantitative analyses utilized multilevel logistic regression; qualitative analysis used inductive and deductive methods. These data informed a conceptual model.

Key Results

Of 58,408 HCWs (median response rate 32%), 1022 were hospital-based clinicians (906 (89%) physicians; 449 (44%) female; 469 (46%) White); 46% of these hospital-based clinicians reported burnout. Work overload was associated with almost 5 times the odds of burnout (OR 4.9, 95% CIs 3.67, 6.85, p < 0.001), and those with anxiety or depression had 4 times the odds of burnout (OR 4.2, CIs 3.21, 7.12, p < 0.001), while those feeling valued had half the burnout odds (OR 0.43, CIs 0.31, 0.61, p < 0.001). Regression models estimated 42% of burnout variance was explained by these variables. In open-ended comments, leadership support was helpful, with “great leadership” represented by transparency, regular updates, and opportunities to ask questions.

Conclusions

In this national study of hospital medicine, 2 variables were significantly related to burnout (workload and mental health) while two variables (feeling valued and leadership) were likely mitigators. These variables merit further investigation as means of reducing burnout in hospital medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

COVID-19 has been a stressor for healthcare workers like no other. Hospitalists in particular carried a large share of the load during the pandemic by caring for many acutely ill patients with uncertain prognoses in the context of constantly changing COVID-related guidelines. 1,2 Early in the pandemic, stress among hospitalists was in the top 5 of all specialties, approaching that seen in Emergency Medicine.3 The pandemic significantly impacted physician worklife and wellbeing. Physician burnout increased during COVID-19, 4,5 with burnout (which includes emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and lack of sense of accomplishment) in excess of 60% of all practicing physicians by late 2021, the highest levels found since physician burnout has been tracked. In a 2015 survey, 183 academic hospitalists had a lower burnout rate (33%) than 396 general internists in ambulatory care (40%); hospitalists differed from ambulatory clinicians in describing their worklives (with more frequent endorsement of good teamwork, as well as less documentation time pressure and less electronic medical record time spent at home), suggesting there may be unique contributors to worklife in hospital medicine. 6

Burnout is associated with intention to leave, intention to reduce hours and suicidal ideation. 7,8,9 Stress and burnout have disproportionately impacted certain groups (women, younger faculty).10 The American Medical Association’s (AMA) Coping with COVID-19 survey has highlighted issues for critical care physicians and nurses 8 and a diverse sample of healthcare workers (HCWs) in numerous work roles; 10 the survey has also connected burnout to work intentions among clinicians and nurses. 7 However there have been few recent studies of hospitalists, with no large scale studies during the pandemic. (A recent excellent article studied 52 hospitalists at one medical center. 2) Most prior studies have been of academic hospitalists, 11,12 with little known outside of academic centers. The national survey through the Association of Chiefs and Leaders of General Internal Medicine (ACLGIM) showed differences between hospital medicine clinicians and ambulatory internists, suggesting worklife may be different in hospital medicine. 6 A recent paper in JGIM 13 described promising worklife interventions in hospital medicine, including improvements in communication (transparent and frequent), wellness resource offerings (related to nutrition and sleep), clear return to work guidelines, increased mental health resources, inpatient use of telemedicine, childcare/elder care resources, and changes in inpatient scheduling, but the evidence base for their use is evolving. Thus, we felt a study of remediable risk factors for burnout in a larger sample of hospital-based clinicians could contribute to the literature.

A recent conceptual framework for hospitalist workforce adaptations 14 considered roles of hospitalists during the pandemic, incorporating adaptations employed during the early pandemic, clinical and operational aspects of work, system constraints, and associations with patient and workforce outcomes. We used this framework to refine our understanding of how hospitalist clinicians (defined as physicians and Advanced Practice Clinicians (APCs) in hospital medicine) coped with COVID-19. We hypothesized that use of the framework could highlight actionable changes to prevent, mediate, and reverse burnout among hospitalists.

Methods

The previously described Coping with COVID-19 survey 3,7,10 involved more than 100 healthcare organizations, many of whom were invited by the AMA to participate. Individual health systems distributed surveys electronically and results were returned to a data lab, Forward Health Group (Madison, WI). Conducted between April of 2020 and March of 2021, the study assessed aspects of worklife (referring to what happens during time one spends at ones job compared with time spent at home) as well as outcomes including satisfaction, burnout, and intent to reduce hours or leave the job. The current study included responses from April 30 until December 12, 2020. Those surveyed (see Coping with Covid survey questions in Appendix, Fig. 1A) included HCWs in varied roles. The current study focuses on those in hospital medicine (physicians and APCs), referred to as hospital-based clinicians. Burnout was measured with the single item Mini-Z assessment (correlated with emotional exhaustion on the Maslach Burnout Inventory 15), then dichotomized in the standard manner 3 into those who were “burned out” and those “not burned out” (choices c, d and e, each of which mention burnout, represent “burnout”). The author team assessed worklife elements which might be associated with burnout on 4 point scales (see survey in Appendix), usually with the top two choices representing an item or topic being present, including work overload (top two categories = work overload), anxiety/depressive symptoms due to COVID-19 (top two choices = present), fear of exposure to COVID or transmission to loved ones (top two responses = “fear”), mission/purpose (top two categories = present), childcare stress (top two responses = childcare stress present) and feeling valued, a burnout mitigator (top two responses = feeling valued). Cutoffs for dichotomizing were consistent with prior Coping with Covid studies 10 and variables selected in part from prior studies (e.g. prior hospitalist surveys 6). These single item assessments have performed well in correlations with clinician outcomes. 3 Respondents could provide open-ended comments on stressors. To guide analyses, the authors used the conceptual framework for hospitalist workforce adaptations which considered hospitalist activities plus system constraints and innovations. 14

Quantitative Analysis

Univariate statistics and bivariate comparisons were performed to assess associations with burnout, followed by multilevel logistic regressions, controlling for clustering of clinicians within organizations and adjusting for covariates of race and ethnicity, sex and years in practice.

Qualitative Analysis

Surveys included a free-text prompt, “What else would you like to tell us about your experience during the COVID-19 crisis?” As in other national survey reports, we used a method of examining comments at the survey’s end to learn about respondent’s thoughts and feelings, 16,17 adding richness and texture to quantitative findings. To do so, we took the variable most strongly correlated with burnout (work overload) and selected all available comments from those with the highest work overload, and those not at all concerned about work overload, performing a formal content analysis on responses from these two groups to learn the important issues for hospitalist clinicians in favorable vs unfavorable work environments represented by degree of work overload. Comments ranged from four words to three sentences. Using a grounded theory approach, three of the authors (AB, ES, LL) used standard techniques to identify emerging and recurring themes 18,19. These authors then met to discuss the major themes prior to applying them to the data. Reviewers thematically indexed and coded the data following principles of content analysis. 19,20 After coding, the authors met to review results and reach consensus. Coping with Covid was deemed a quality improvement/program evaluation project exempt from research requirements by the Hennepin Healthcare Institutional Review Board as a low risk, non-interventional study.

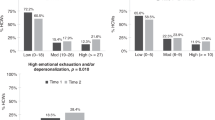

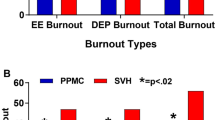

Results

Respondent demographics are summarized in Table 1. There were 58,408 HCWs who responded to this sample from the Coping with Covid survey (with a median response rate of 32%); among these, there were 13,780 physicians and 3705 APCs with data on burnout, with 1022 hospitalist clinicians (906 (89%) physicians; 449 (44%) female, 469 (46%) White, 222 (22%) Asian, 146 (14%) preferring not to identify race or ethnicity; and 514 (50%) in practice < = 10 years). Forty-six percent of hospital-based clinicians met criteria for burnout (46% of hospitalist physicians and 48% of hospital-based APCs), vs 58% of critical care clinicians, 52% of family medicine clinicians and 49% of infectious disease specialists. Factors associated with burnout in prior Coping with COVID-19 analyses, 3,7,10 including fear of exposure, work overload, sense of mission/purpose, and anxiety and depression due to COVID-19-related care, were tested for association with burnout (Table 2). Variables were entered into a regression model (main results in Table 3, Supplemental Table 1A with full model including adjusting covariates). These analyses identified work overload as the strongest correlate of burnout (Odds Ratio 4.9 (95% CIs 3.67, 6.85, p < 0.001). Those with high anxiety or depression from COVID-19-related work had 4 times the odds of burnout (OR 4.2, CIs 3.21, 7.12, p < 0.001), while hospital-based clinicians who felt valued by their organizations had about half the odds of experiencing burnout (OR 0.43, CIs 0.31, 0.61, p < 0.001). Figure 1 shows significant differences in these variables by those with and without burnout. Sense of mission and purpose was not a significant factor in the model. The McKelvey Zavoina pseudo R-squared demonstrated that the model explained 42% of variance in burnout.

Qualitative comment analysis (see Consort Diagram, Supplementary Fig. 2A).

Approximately 55% of hospital-based clinician respondents included comments (517 total comments, after removing n/a or no response cells). The team extracted and reviewed open-ended comments from respondents on the extreme ends of the work overload scale, that is those not experiencing any work overload (n = 107 with comments representing those respondents with no work overload) or those experiencing work overload to a great extent (n = 109 representing those respondents with extreme work overload). There were 10 total themes identified, with 3 unique to the extreme work overload group, 4 unique to those with no overload, and 4 shared between both groups (see Fig. 2). The “extreme work overload” group had 3 unique themes emerge: 1) work/family balance disruption, 2) time needed to recover from work-related exhaustion, and 3) not feeling valued or supported by leadership or administration. Themes identified as unique to the “no work overload” group included 1) concerns about hospital visitor policies, 2) needing emotional support, 3) feeling valued, and 4) support by leadership. When feeling valued was present, it included comments such as, “I work at an institution that has been prepared for the pandemic, is proactive in equipping us with what we need, and is good at appreciating us”, and “I appreciate the planning that went into preparing for COVID-19 and the flexibility in responding to changing workload and environment.” Meanwhile, comments about leadership in the extreme work overload group were largely negative: (“(I) do not feel supported by our administration…they have taken away a number of resources to help in patient care and expect us to do more with less”), while in the no work overload group, clinicians had positive comments about their leadership (“I feel supported and safe at work. The hospital and team leadership work hard to ensure we are safe.”). Table 4 includes representative quotes from each group related to feeling valued and leadership support. Both groups (no work overload and extreme work overload), shared similarities in their comments, with 4 common themes: 1) concerns about safety (access to personal protective equipment (PPE) and COVID-19 testing); 2) worry about exposing others (e.g. family at home); 3) challenges of keeping track of constantly changing policies; and 4) sentiments that the state or government needs to do more to address the pandemic. Figure 2 shows overlapping and non-overlapping themes from these groups.

Discussion

In this national study of 1022 hospital-based physicians and APCs during the early stages (April 2020-December 2020) of the pandemic, we applied a conceptual framework for explaining and mitigating burnout in this important population of healthcare workers. Hospital medicine had unique challenges during the pandemic, as did other groups managing acutely ill patients, including emergency medicine, critical care and infectious disease clinicians. In our sample of hospital-based clinicians, close to half were burned out. The results were both distressing and uplifting. Hospitalists shared significant challenges and lack of support as well as innovative opportunities for improvement and even numerous success stories seen in Table 3 (great teamwork, transparent communication with regular updates, feeling safe, and supportive leadership). The most highly correlated variables with burnout were work overload, and anxiety and depression due to COVID-19-related care, which, if confirmed in prospective trials, would offer opportunities to address burnout through 1) defining what a reasonable workload is at the individual level, then developing means for real-time adaptation of workload to individual and team capacity, and 2) building in resources for on-site (accessible) and off-site (more confidential) mental health resource availability. Finally, the importance of feeling valued was demonstrated in this group of clinicians, as it has been shown to be meaningful in other HCWs and clinicians. 3 How to promote feeling valued in hospitalist clinicians is a point for investigation. This large scale, data driven, model-validating study (to our knowledge, the largest study of hospital medicine in the past decade) during the “stress test” of the pandemic provides direction for needed study and action, as there are few such surveys to rely upon to guide current worklife interventions in hospital medicine, and burnout rates in medicine remain high as the effects of the pandemic unfortunately continue to linger.

Work overload is significantly associated with higher burnout. The comments and context of stressed clinicians bring urgency to the need for medicine to join other disciplines that measure workload and reduce work when workers are tired or stressed (e.g., as in the airline industry). As staffing shortages grow, 21,22 there is a pressing need to evaluate work structure and culture, right-size workload for capacity of those performing it, and ensure adequate numbers of clinicians to account for those who cannot work because they or their families are sick. In this late stage of the pandemic, thoughtful approaches to workload modulation can be implemented and developed, and then held in reserve for the future should more challenging times return.

Meanwhile, feeling valued was a striking protective factor which was significantly associated with lower burnout even in the context of system constraints such as PPE shortages, changing treatment guidelines and isolation requirements. This offers the opportunity for “quick wins,” allowing organizational leadership to assess what matters most to their workforce in terms of feeling valued, and then rapidly responding. As noted, making people feel valued is described as not just appreciating people; it also encompasses being responsive to workload, and giving people the resources they need to do their jobs. While sense of mission and purpose was present more often in hospital-based vs other clinicians (Table 2), it was not significant in its relationship to burnout in regression models. This variable could be pursued in future studies as a factor of potential importance.

The open-ended comments focused attention on leadership: leadership has impact, and organizational leadership makes a difference, as in work by Dyrbye and colleagues. 23 Leadership could be a moderator of burnout from work overload and anxiety by changing the impact of stressors if leaders are engaged and responsive and given leeway by their organizations to do so. Clearly, there are challenges to how a system can address a time when work overload is endemic; involving workers in decision making about this, and customizing workloads to individuals’ abilities to take work duties on, may provide a sustainable way forward. Transparent communication was frequently noted as a specific way in which leadership was supportive. The Hospitalist Well-Being Advocates Toolkit 24 from the Society of Hospital Medicine portrays recommendations for leaders for excellent leadership and for leader self-care. Our data suggest listening carefully to HCWs and implementing support may relate to improved satisfaction and thus to retention when future crises occur.

Anxiety and depression related to COVID-19 was the other variable significantly associated with burnout. While the data promote system changes to reduce mental health stressors, there is also a role for on- or off-site care and ready access to mental health resources for alleviation of symptoms. COVID-19 care is stressful, even with good protection, and it is ideal that mental health providers are immediately and confidentially available. Rush University’s wellness consult service, with mental health leaders rounding on frontline staff, is a powerful example of being there for clinicians with “in the moment” care. 25 Other examples include coaching to reduce burnout 26 as well as peer support 27 and buddy programs. 28 Transparent communication from leaders may also mitigate clinician anxiety.

We expanded the conceptual model of hospitalist function and outcomes to account for these variables (workload, mental health symptoms, feeling valued, and leadership, see Appendix Fig. 3A for final model). This model can be tested for its validity in guiding healthcare interventions to improve worklives of hospital-based clinicians.

Our study has several limitations. The study used a convenience sample of healthcare institutions during the rapidly evolving early phase of the pandemic, lacking details around institutional data (e.g. academic vs non-academic, or geographic location). Childcare stress was assessed and while it did not have a statistically significant relationship here (OR 1.5, p = NS), this should be reassessed in future work, as prior studies have demonstrated its importance. 29 Data were collected over less than one year, and the lingering effects of the pandemic were not assessed. Our convenience sample may not be representative of all clinicians, and we have little knowledge of non-respondents. However, our response rate is considerably higher than many national physician surveys. 4 The differential impact of COVID-19 on HCWs in varying roles was not tested. Some organizations were impacted more than others due to different infection rates, resources and local factors which could have affected the findings. Work overload is a subjective assessment, though it has been validated in part through the question from which it was adapted on (lack of) work control, a known predictor of stress and burnout. Finally, several ordered categorical survey items were dichotomized to improve clarity (e.g., percent burned out) which may have decreased sensitivity in seeking variables associated with these outcomes.

Future studies should address variables identified as being critically important by our survey’s hospital medicine respondents: work overload, work-related anxiety/depression (in this case, due to COVID-19), feeling valued, and attention to these issues by leadership. Whether remediating these factors, as suggested by other current study teams 30,31,32,33 will lead to improved and sustainable work conditions with lower burnout remains to be tested in prospective trials.

Further identifying and confirming the factors that lead to distress and burnout, and the impacts of remediating these factors, will be important next steps in addressing the worklives and wellness of our nation’s hospital-based clinicians.

Data Availability

Data may be available from the authors on request.

References

Linker AS, Kulkarni SA, Astik GJ, et al. Bracing for the wave: A multi-institutional survey analysis of inpatient workforce adaptations in the first phase of COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(11):3456–3461.

Glisch C, Yadav S, Bhandari S, et al. Perceptions of burnout among academic hospitalists. WMJ. 2021;120(4):268–272.

Linzer M, Stillman M, Brown R, et al. Preliminary report: US physician stress during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(1):127–136.

Shanafelt TD, West CP, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians during the first 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(12):2248–2258.

Linzer M, Jin JO, Shah P, et al. Trends in clinician burnout with associated mitigating and aggravating factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(11):e224163.

Linzer M, Poplau S, Babbott S, et al. Worklife and wellness in academic general internal medicine: Results from a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1004–1010.

Sinsky CA, Brown RL, Stillman MJ, et al. Covid-related stress and work intentions in a sample of US health care workers. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(6):1165–1173.

LeClaire M, Poplau S, Linzer M, et al. Compromised integrity, burnout, and intent to leave the job in critical care nurses and physicians. Crit Care Explor. 2022;4(2):e0629.

Dyrbye L, R Thomas M, Stanford Massie F, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:334–341.

Prasad K, McLoughlin C, Stillman M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of stress and burnout among U.S. Healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national cross-sectional survey study. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;35:100879.

Glasheen JJ, Misky GJ, Reid MB, et al. Career satisfaction and burnout in academic hospital medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(8):782-785.

Kneeland P. . Success story: Reducing hospitalist burnout with hospitalist-driven improvement initiatives. In AMA Steps Forward: American Medical Association; June 11, 2020. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2766792. Accessed 13 July 2023

Murphy E, Chokshi K, Niranjan-Azadi A, et al. Looking back while thinking forward: Institutional best practices to address hospitalist well-being during COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2023 Apr;38(5):1326–1328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08073-y.

Keniston A, Sakumoto M, Astik GJ, et al. Hospitalists are indispensable in healthcare system COVID-19 responses. SGIM Forum Newsletter. 2021. https://connect.sgim.org/sgimforum/viewdocument/hospitalists-are-indispensable-in. Accessed 21 Nov 2022.

Rohland BM, Kruse GR, Rohrer JE. Validation of a single‐item measure of burnout against the Maslach burnout inventory among physicians. Stress Health. 2004;20(2):75–79.

McMurray JE, Schwartz MD, Genero NP, et al. The attractiveness of internal medicine: A qualitative analysis of the experiences of female and male medical students. Society of General Internal Medicine Task Force on Career Choice in Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(8):812–818.

Anderson E, Solch AK, Fincke BG, et al. Concerns of primary care clinicians practicing in an integrated health system: A qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(11):3218–3226.

Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. 1st ed. New York: Routledge; 2017.

Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. Fourth ed. California: Sage Publications; 2020.

Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Fifth ed. California: Sage Publications; 2017.

Beechly L. Building resilience and well-being: Keys to avoiding the worst of a looming shortage of health care workers. STAT. 2022. Available at https://www.statnews.com/2021/09/27/building-resilience-and-well-being-keys-to-avoiding-the-worst-of-a-looming-shortage-of-health-care-workers/. Accessed February 1, 2023.

Bartlett J. Nursing shortage at mass. Hospitals leads to multimillion-dollar costs. STAT. 2022. Available at https://www.statnews.com/2022/07/13/nursing-shortage-massachusetts-hospitals-multimillion-dollar-costs/. Accessed Feburary 1, 2023.

Dyrbye LN, Major-Elechi B, Hays JT, et al. Relationship between organizational leadership and health care employee burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(4):698–708.

Hospitalist well-being advocates toolkit. August 2022; Available at https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/well-being/. Accessed February 8, 2023.

Adibe B, Hebert C, Perticone K, Dowd SM. Creating wellness in a pandemic: A practical framework for health systems responding to COVID-19. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. 2021;2(2).

Palamara K, Chu JT, Chang Y, et al. Who benefits most? A multisite study of coaching and resident well-being. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(3):539-547.

Shapiro J, Galowitz P. Peer support for clinicians: A programmatic approach. Acad Med. 2016;91(9):1200–1204.

Albott CS, Wozniak JR, McGlinch BP, et al. Battle buddies: Rapid deployment of a psychological resilience intervention for health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(1):43-54.

Harry EM, Carlasare LE, Sinsky CA, et al. Childcare stress, burnout, and intent to reduce hours or leave the job during the COVID-19 pandemic among US health care workers. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(7):e2221776.

Buchbinder M, Browne A, Jenkins T, et al. Hospital physicians' perspectives on occupational stress during COVID-19: A qualitative analysis from two US cities. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(1):176–184.

Palamara K, Sinsky C. Four key questions leaders can ask to support clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic recovery phase. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(1):22–25.

Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2133–2134.

Virginia Medical Society. How does Safehaven™ address confidentiality? Available at https://www.msv.org/programs/physician-wellness/safehaven/. Accessed December 6, 2022.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Sarah Richards for meaningful contributions to this paper in her review.

Funding

This study and other burnout reduction projects are funded by a contract between the AMA and Hennepin Healthcare. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as American Medical Association policy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB study design, writing.

ES. Qualitative analysis, manuscript writing and editing

ML. writing, study oversight and conduct

LL. modeling

RB. Quantitative analysis

SP. Referencing, writing, study oversight.

CS. Study oversight and conduct, critical review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Becker was supported by the AMA for burnout related work. Dr. Linzer and Ms. Poplau are supported through their place of employment (Hennepin Healthcare) by the American Medical Association (AMA), Optum Office for Provider Advancement, Institute for Healthcare Improvement and the California Area Health Education Center system for burnout prevention projects; Dr. Linzer is also supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to lead a Learning Health System K12 training program. Dr. Sinsky is employed by the AMA. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as AMA policy. The authors have no other conflicts to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Becker, A., Sullivan, E.E., Leykum, L.K. et al. Burnout Among Hospitalists During the Early COVID-19 Pandemic: a National Mixed Methods Survey Study. J GEN INTERN MED 38, 3581–3588 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08309-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08309-x