Abstract

Background

Missed appointments (“no-shows”) are a persistent and costly problem in healthcare. Appointment reminders are widely used but usually do not include messages specifically designed to nudge patients to attend appointments.

Objective

To determine the effect of incorporating nudges into appointment reminder letters on measures of appointment attendance.

Design

Cluster randomized controlled pragmatic trial.

Patients

There were 27,540 patients with 49,598 primary care appointments, and 9420 patients with 38,945 mental health appointments, between October 15, 2020, and October 14, 2021, at one VA medical center and its satellite clinics that were eligible for analysis.

Interventions

Primary care (n = 231) and mental health (n = 215) providers were randomized to one of five study arms (four nudge arms and usual care as a control) using equal allocation. The nudge arms included varying combinations of brief messages developed with veteran input and based on concepts in behavioral science, including social norms, specific behavioral instructions, and consequences of missing appointments.

Main Measures

Primary and secondary outcomes were missed appointments and canceled appointments, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Results are based on logistic regression models adjusting for demographic and clinical characteristics, and clustering for clinics and patients.

Key Results

Missed appointment rates in study arms ranged from 10.5 to 12.1% in primary care clinics and 18.0 to 21.9% in mental health clinics. There was no effect of nudges on missed appointment rate in primary care (OR = 1.14, 95%CI = 0.96–1.36, p = 0.15) or mental health (OR = 1.20, 95%CI = 0.90–1.60, p = 0.21) clinics, when comparing the nudge arms to the control arm. When comparing individual nudge arms, no differences in missed appointment rates nor cancellation rates were observed.

Conclusions

Appointment reminder letters incorporating brief behavioral nudges were ineffective in improving appointment attendance in VA primary care or mental health clinics. More complex or intensive interventions may be necessary to significantly reduce missed appointments below their current rates.

Trial Number

ClinicalTrials.gov, Trial number NCT03850431.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

BACKGROUND

Missed appointments, frequently referred to as “no-shows,” are a longstanding challenge to providers and administrators in every healthcare system. In the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the largest integrated healthcare system in the USA, the national missed appointment rate was 14.9% from October 2020 to September 2021, resulting in 10,109,148 missed appointments.1 Patients prone to miss appointments are a vulnerable population, known to have higher rates of preventable hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and all-cause mortality.2,3

Like many behaviors, the potential reasons behind a missed appointment are myriad, but broadly speaking they can include patient-related characteristics (e.g., history of psychiatric disorders4), features of the healthcare system (e.g., scheduling systems5), and factors that lie in between the two (e.g., how long prior to the scheduled date the appointment was scheduled).6 Nonetheless, simply forgetting the appointment is perhaps the single most common reason for a missed appointment.7 Given this, it is not surprising that appointment reminders are employed more or less universally across healthcare systems—a straightforward, first line of defense against missed appointments. Traditionally, appointment reminders provide a “bare bones” message about the time, date, and place of an appointment, which is more or less how they have been for at least the last 40 years.8,9,10

One of the core ideas of behavioral economics is the idea of supporting behavior change through the use of nudges: small alterations in how options are presented that are designed to influence a person’s decision making without restricting their choices.11,12 Several studies have found promising impacts on appointment attendance through application of nudges that leveraged principles such as people’s general desire to avoid physical or emotional losses (“loss aversion”) and adhere to prevalent social norms.13,14,15,16 Specifically, a randomized controlled trial in outpatient specialty clinics in the UK’s National Health Service found that specifying the cost of a missed appointment to the healthcare system significantly reduced the rate of missed appointments, and including the descriptive social norm that most patients attended their appointment significantly increased the rate of canceling appointments in advance, thus potentially averting missed appointments.17 An Israeli study found several messages effective at reducing missed appointments, the most effective being a text message appointment reminder designed to evoke emotional guilt (“Not showing up to your appointment without canceling in advance delays hospital treatment for those who need medical aid.18) Finally, in the USA, a randomized trial of 360 veterans at a single VA medical center who were referred to specialty mental health for depression found that patients who received an appointment reminder letter containing a bolded, gain-framed message (“If you go to your appointment, you will learn ways to improve your mood and emotional well-being. Also, if you see your provider, he/she will be able to work with you to help you get the most out of your treatment.”) were more likely to attend their appointments, compared to those who received a routine letter without the additional message.19

To date, there have been no large-scale trials of behavioral economics-informed appointment reminders in the USA. Moreover, the effect of other types of nudges, or combining nudges, is not known. The aim of this study was to conduct a large-scale pragmatic trial within the VA to evaluate the effect of a series of nudges on missed and canceled appointments. We hypothesized that the intervention, as compared with usual care, would have a lower missed appointment rate and higher canceled appointment rate. We also hypothesized that effect size of nudges would vary by intervention arm such that some types of nudges would have a larger proportional effect than others.

METHODS

Design and Setting

We conducted a cluster randomized controlled pragmatic trial at the VA Portland Health Care System, which cares for approximately 85,000 patients across Oregon and southwest Washington, including two medical centers (Portland and Vancouver) and six satellite clinics (Hillsboro, Fairview, West Linn, Salem, Bend, and North Coast).

Pragmatic trial features included broad eligibility criteria, intervention implementation integrated with usual care, usual care as the comparison condition, and outcome assessment using electronic health record data.20,21 The trial began December 2019 but was halted in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It resumed October 2020 and lasted 1 year until October 2021. Due to cohort effects and a small sample size, pre-COVID trial data were not included. The VA Portland Healthcare System Institutional Review Board and Research and Development Service approved the study, which was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (Trial number NCT03850431) prior to initiation.

For inclusion, outpatient appointments had to be as follows: (1) in either primary care or mental health; and (2) scheduled at least 2 weeks before the appointment date (the minimum length of time used to determine whether an appointment reminder is mailed). We used “stop codes,” 3-digit identifiers used within VA,22 to identify appointments as primary care (codes: 322, 323, and 338) or mental health (codes: 502, 513, 527, 534, 542, 545, and 562). Patients were included if they had at least one appointment meeting the above criteria.

Randomization and Masking

We conducted randomization at the provider (not patient) level by allocating to one of four nudge (intervention) arms or control arm (1:1:1:1:1), and stratifying by setting (primary care or mental health) and location (Portland, Vancouver, or other). A statistician (MN) masked to intervention information used block randomization with random block sizes of 5, 10, or 15, assigning providers to one of five study arms using the blockrand (v 1.5) R package23.

Interventions

We developed four nudge arms using a combination of theory, empirical data, and veteran input. We began with candidate messages organized around broad concepts in behavioral science that seemed plausible motivators for a patient to attend and/or cancel their appointment: social norms, behavioral instructions and intentions, consequences for self, and consequences for others (Table 1). We then employed a user-centered design (UCD) process as a strategy to make our interventions patient-centered and minimize potential risks and unintended consequences as reported previously.24 During the UCD process, we conducted iterative waves of interviews with veterans, eliciting feedback on nudge language and the draft interventions. Interviews influenced key aspects of intervention content, ultimately resulting in removal or revision of several candidate nudge messages, generation of new messages, and selection of specific combinations of messages for each intervention. The four finalized interventions are summarized in Table 1. To illustrate how the intervention appeared in practice, Fig. 1 presents the letter for arm D, which contained a combination of all the nudges, as seen by a veteran with a primary care appointment.

Consistent with our pragmatic trial approach, interventions were delivered as they would be in routine clinical practice. This meant scheduling staff, who were unaware of study hypotheses or procedures, were responsible for preparation and mailing of templated appointment reminders. For mental health clinics, routine practice included not only an appointment reminder but also a letter after a missed appointment; therefore, nudge messages for each intervention were incorporated into these letters too. One unmasked research team member (EM) worked with clinic staff to modify, maintain, and audit letter templates.

Control Arm

The control arm consisted of routine appointment reminder letters providing the clinic name, location, provider, date and time of appointment, and contact information. Since reminder letters were the focus of this trial, patients in all study arms continued to receive automated phone (audio), text, and postcard reminders (primary care only) without the nudge messages.

Main Measures

We used the VA Corporate Data Warehouse to identify eligible appointments and coded as completed, canceled (by patient), or missed (“no-show”). Appointments that could not be classified due to incomplete data were excluded (0.05%). The primary outcome was whether a patient missed an appointment. In accordance with VA policy, an appointment was considered missed if marked by clinic staff as a “no-show” or if canceled by the patient or clinic after the appointment time. The missed appointment rate equals the number of missed appointments divided by the number of completed and missed appointments. Our secondary outcome was whether a patient canceled their appointment. As clinics sometimes cancel appointments for administrative reasons and the focus of our trial was patient behavior, we examined only appointments canceled by patients with a timestamp prior to the scheduled appointment time and calculated a cancelation rate accordingly. The canceled appointment rate equals the number of canceled appointments divided by the number of completed, canceled, and missed appointments.

Statistical Analyses

We first compared patient demographics and clinical characteristics between the control and intervention groups (both combined and individually), using counts and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations (SD) for quantitative variables. We used standardized mean differences (SMD)25 to compare the effect size between the control and combined intervention groups. For patients with multiple appointments during the study period, we used data from their first appointment in primary care and mental health, respectively, to summarize baseline patient-level characteristics.

The primary analyses compared the odds of a missed appointment between the control and the combined intervention groups using appointment-level logistic regression models with non-nested clustering for repeated appointments among providers and patients26. Primary care and mental health appointments were analyzed separately. We ran unadjusted and adjusted models, which included age, gender (missing values for self-identified gender were imputed with sex), race (collapsed as white, non-white, and unknown), ethnicity, rurality, VA disability rating,27 mental health diagnosis in the prior 2 years (i.e., depression, PTSD, substance use disorder), Elixhauser comorbidity score,28 Care Assessment Need (CAN) score29 (estimated probability of readmission or death within 90 days in primary care sample only), provider type, appointment age, appointment modality (virtual vs. in-person), appointment location (Portland, Vancouver, or other 6 sites combined), and the number of prior visits for the patient at the provider’s clinic location in the past 2 years. We selected covariates based on significance in our models and prior literature demonstrating associations with missed appointments (e.g., demographic characteristics, rurality, disability rating as a proxy for socioeconomic and health insurance status, mental health history, appointment age).4,30,31,32 Variance inflation factors were checked for multicollinearity, and all were less than 2.15. Patient characteristics were non-varying, using the values from the first appointment if they had repeated appointments in either setting. We also ran separate models with intervention × gender and intervention × modality interactions. In addition to odds ratios, we calculated mean predicted probabilities and 95% confidence intervals for each intervention via 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations, using reference levels for categorical variables and mean values for continuous covariates.

We conducted two sensitivity analyses. To address the possibility of diminished effect after repeated exposure to the intervention, the first sensitivity analysis was restricted to each patient’s first appointment (separately for primary care and mental health). To provide a more accurate estimate of the standard errors, we used logistic generalized estimating equation models with clustering for providers using an exchangeable covariance structure.33,34 The second sensitivity analysis was restricted to primary care providers (in primary care) and therapists and prescribers (in mental health); this was done to avoid including appointments with other providers (e.g., nurses, pharmacists) who frequently have “group appointments” that did not receive appointment reminder letters. All analyses were repeated using all five study arms with the control group as the reference level, and again for the cancelation outcome. Analyses were run in R (v. 4.1.2)35 using the smd (v. 0.6.6),36 lmtest (v. 0.9–40),37 sandwich (v. 3.0.2)26,38 (vcovCL for two-way clustering), and geepack (v. 1.3.9)39,40,41 packages. All tests were two-sided with a significance threshold of 5%.

RESULTS

Patients and Clinics

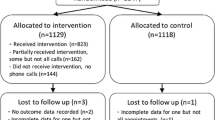

Two hundred thirty-one primary care providers had 27,540 unique patients with a total of 49,598 appointments in the trial. Likewise, 215 mental health providers had 9420 unique patients with a total of 38,945 appointments. Thirty-six percent of primary care (70% of mental health) patients had more than one appointment included in the study. Of these, 13% (29%) had appointments with multiple providers. Because study arm randomization was at the provider level, this led to 11% (25%) of patients having appointments in more than one study arm within primary care and/or mental health. Consort flowcharts are presented in Fig. 2.

Consort flow diagrams for primary care (a) and mental health (b). Consort Flow Diagram for Primary Care (2a). * Some patients had appointments in multiple arms of the study, so the sum of patients in each arm will not equal the number of unique patients in the trial. † Ineligible appointments refer to appointments (1) made fewer than two weeks in advance (N = 74,148 across all arms) or (2) appointments canceled by the clinic before the appointment time (e.g., provider out sick) or created for operational, not clinical, purposes (N = 5,815 across all arms). ‡ Some providers assigned an intervention reminder letter did not have appointments that met trial criteria. There were 231 providers and 27,540 unique patients across all arms. Consort Flow Diagram for Mental Health (2b). * Some patients had appointments in multiple arms of the study, so the sum of patients in each arm will not equal the number of unique patients in the trial. † Ineligible appointments refer to appointments (1) made fewer than two weeks in advance (N = 66,821 across all arms) or (2) appointments canceled by the clinic before the appointment time (e.g., provider out sick) or created for operational, not clinical, purposes (N = 4,324 across all arms). ‡ Some providers assigned an intervention reminder letter did not have appointments that met trial criteria. There were providers clinics and 9,420 unique patients across all arms

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, most patients were white, male, and not Hispanic or Latino, and resided in urban areas; mean age was 63.7 years (primary care) and 50.0 (mental health).

Primary Outcome

In both primary care and mental health, there was no significant effect of nudges on missed appointment rate (Table 4).

In primary care, the missed appointment rates for the intervention arms (all four nudge arms combined) and control group, respectively, were 11.1% and 11.9%. The odds ratio (OR) from the adjusted logistic regression model comparing the intervention arms to the control arm was 1.14 (95% CI = 0.96–1.36, p = 0.15; control arm: 10.9%, 95% CI = 10.0–13.7%; all nudge arms: 12.2%, 95% = 11.2–15.2%), which was the reverse relationship of the unadjusted percentages. When comparing nudge arms individually to the control arm, the OR’s ranged from 1.11 to 1.18 and were nonsignificant (control arm: 9.3%, 95% CI = 8.4–11.9%; nudge arms varied from 10.2 to 10.8%).

In mental health, the missed appointment rates for the intervention arms (all four nudge arms combined) and control group, respectively, were 20.1% and 18.0%. The OR from the adjusted logistic regression model comparing the intervention arms to the control arm was 1.20 (95%CI = 0.90–1.60, p = 0.21; control arm: 18.9%, 95% CI = 17.1–24.4%; all nudge arms: 21.8%, 95% = 20.4–25.9%). When comparing nudge arms individually to the control arm, the OR’s ranged from 1.14 to 1.33 and were nonsignificant (control arm: 19.2%, 95% CI = 17.3–24.9%; nudge arms varied from 21.4 to 23.9%).

Secondary Outcome

In both primary care and mental health, there was no effect of nudges on canceled appointment rate (Table 4).

In primary care, the cancelation rates for the intervention arms (all four nudge arms combined) and control arm, respectively, were 7.3% and 6.0%, again with a “reversed” OR of 0.92 (95%CI = 0.83–1.03, p = 0.15) when comparing the intervention to the control in the adjusted logistic regression model. When comparing nudge arms individually to the control arm the OR’s ranged from 0.89 to 0.95, all nonsignificant.

In mental health, cancelation rates for the intervention arms (all four nudge arms combined) and control arm, respectively, were 8.8% and 10.2%, with an OR of 0.83 (95%CI = 0.65–1.06, p = 0.14) when comparing the intervention to the control group in the adjusted logistic regression model. When comparing nudge arms individually to the control arm the OR’s ranged from 0.74 to 0.93, all nonsignificant.

Additional Analyses

In primary care, modality of appointment (OR = 0.74, 95%CI = 0.57–0.98, p = 0.03) and gender (OR = 0.71, 95%CI = 0.53–0.95, p = 0.02) both moderated the missed appointment rate, such that missed visits were more likely in the intervention group compared to the control group for virtual appointments and men, while less likely for in-person appointments and women. For the cancelation rate in primary care, only modality of appointment was a significant moderator (OR = 1.34, 95%CI = 1.06–1.69, p = 0.02), where virtual appointments in the nudge arms were less likely to be canceled than in the control group, and more likely for in-person appointments. In mental health, the only significant moderator was gender for canceled appointment rate (OR = 0.73, 95%CI = 0.53–0.99, p = 0.04), where both men and women in the intervention group were less likely to cancel appointments than in the control group, but men more so than women.

For sensitivity analyses, results were generally very similar with two minor exceptions. First, in primary care, when restricting to the patients’ first appointment, the canceled appointment rate was lower for the intervention arms compared to the control arm (OR = 0.88, 95%CI = 0.78–1.00, p = 0.04) in the adjusted model. Second, in mental health, when restricting to the patients’ first appointment, the missed appointment rate for arm C (Consequences for Others) was lower compared to that of the control arm (OR = 0.67, 95%CI = 0.45–0.98, p = 0.04).

DISCUSSION

In this yearlong pragmatic trial composed of tens of thousands of VA patients and their appointments in primary care and mental health, we found no effect of incorporating nudges in appointment reminder letters on measures relevant to outpatient appointment attendance, specifically the rate of missed appointments and rate of canceled appointments. The lack of effectiveness of incorporating nudges was seen consistently in comparing all four intervention arms to the control, in comparing each individual intervention arm to the control arm, and in both primary care and mental health, the two largest clinic types in VA. While this was a negative trial, we believe our findings are revealing and important to disseminate, particularly in light of recent analyses suggesting substantial publication bias in the realm of nudge interventions, and perhaps even null effects after accounting for this bias.42,43

As a pragmatic trial, our findings may have been impacted by several real-world issues within the VA healthcare system. First, a number of veterans were in more than one study arm, particularly among patients in mental health. Psychiatric comorbidity among VA-using veterans is common, and this likely contributed to patients being seen by multiple mental health providers.44 Second, patients’ exposure to the intervention was limited compared to what they would have received in a more traditional efficacy trial. For instance, formatting restrictions in the systems used to create reminder letters prevented us from doing more to highlight messages. Furthermore, our trial was only able to incorporate nudges into appointment reminder letters. This left other reminders (text, audio, postcard, and—for virtual appointments that became commonplace during the trial—email) untouched by the intervention. As a consequence, patients may have experienced a diluted effect of the nudge due to varying messages being delivered for the same appointment, and they may also have experienced reminder fatigue,45 leading some to effectively ignore reminders altogether.

Our trial was also susceptible to a variety of “on-the-ground” changes in healthcare operations that occurred over the course of the trial. COVID-related impacts included a large-scale switch to virtual appointments, and processes related to this change may have diminished relevance and impact of the trial’s different patterns of outreach to patients. For instance, during the trial it became standard practice for providers to call a patient if they did not log into a virtual appointment, thereby potentially creating a new intervention and obviating a missed appointment. We were also unable to quantify the fidelity of the intervention and cannot guarantee that the offices preparing and sending the appointment reminder letters consistently followed standard procedures.

While our pragmatic trial was large, it was nonetheless limited to a single VA healthcare system among patients who were primarily White, male, and older adults. Findings could differ in other patient populations.

It is also plausible that no intervention focused simply on appointment reminders may be able to create significant change in appointment attendance. Financial incentives—whether framed as a gain or loss—can be used to influence health behaviors, though their cost-effectiveness would need to be considered.46 A recent systematic review of missed appointments in diabetes clinic appointments found that qualitative studies suggest psychosocial factors playing a prominent role.47 It may be, then, that even in the best of circumstances, nudges embedded into appointment reminders are inadequate to resolve the mixture of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral factors involved in triggering missed appointments. In that case, it may be up to health systems and their researchers to determine whether to deploy and test interventions that are more costly or higher intensity, or both. Perhaps a 10% missed appointment rate in primary care or a 20% missed appointment rate in mental health clinics is as good as can be practically achieved without addressing the larger social and contextual issues underling missed appointments.

In conclusion, in this large pragmatic trial in primary care and mental health clinics, we found appointment reminder letters incorporating brief behavioral nudges did not affect appointment attendance. Attempts to reduce missed appointments or increase cancelation of appointments that are no longer necessary likely require more complex or intensive interventions.

Data Availability

A de-identified, anonymized dataset resulting from this study may be shared. Requests for data access should be made in writing to the corresponding author and provide information on the purpose for accessing the data.

References

VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI). No Show and Cancellation Summary Report. Internal U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Report: Unpublished

Hwang AS, Atlas SJ, Cronin P, et al. Appointment “no-shows” are an independent predictor of subsequent quality of care and resource utilization outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1426-1433. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3252-3

McQueenie R, Ellis DA, McConnachie A, Wilson P, Williamson AE. Morbidity, mortality and missed appointments in healthcare: a national retrospective data linkage study. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1234-0

Dantas LF, Fleck JL, Cyrino Oliveira FL, Hamacher S. No-shows in appointment scheduling – a systematic literature review. Health Policy. 2018;122(4):412-421. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.02.002

Lacy NL. Why We Don’t Come: Patient Perceptions on No-Shows. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(6):541-545. doi:https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.123

Milicevic AS, Mitsantisuk K, Tjader A, Vargas DL, Hubert TL, Scott B. Modeling Patient No-Show History and Predicting Future Appointment Behavior at the Veterans Administration’s Outpatient Mental Health Clinics: NIRMO-2. Mil Med. 2020;185(7-8):e988-e994. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usaa095

Goffman RM. National Initiative to Reduce Missed Opportunities Mental Heath Operations Call. VA Pittsburgh Veterans Engineering Resource Center (VERC); 2016.

Bigby J, Giblin J, Pappius EM, Goldman L. Appointment reminders to reduce no-show rates. A stratified analysis of their cost-effectiveness. JAMA. 1983;250(13):1742–1745.

Macharia WM, Leon G, Rowe BH, Stephenson BJ, Haynes RB. An overview of interventions to improve compliance with appointment keeping for medical services. JAMA. 1992;267(13):1813-1817.

Parikh A, Gupta K, Wilson AC, Fields K, Cosgrove NM, Kostis JB. The Effectiveness of Outpatient Appointment Reminder Systems in Reducing No-Show Rates. Am J Med. 2010;123(6):542-548. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.11.022

Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Revised and expanded edition. Penguin Books; 2009.

Schmidt AT, Engelen B. The ethics of nudging: An overview. Philos Compass. 2020;15(4). doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12658

Hastie R, Dawes R. Rational Choice in an Uncertain World: The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making. 2nd ed. SAGE Publications, Inc; 2001.

Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica. 1979;47(2):263-292.

Bauer BW, Tucker RP, Capron DW. A Nudge in a New Direction: Integrating Behavioral Economic Strategies Into Suicide Prevention Work. Clin Psychol Sci. 2019;7(3):612-620. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618809367

Fischer EP, McSweeney JC, Wright P, et al. Overcoming Barriers to Sustained Engagement in Mental Health Care: Perspectives of Rural Veterans and Providers. J Rural Health Off J Am Rural Health Assoc Natl Rural Health Care Assoc. 2016;32(4):429-438. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12203

Hallsworth M, Berry D, Sanders M, et al. Stating Appointment Costs in SMS Reminders Reduces Missed Hospital Appointments: Findings from Two Randomised Controlled Trials. Gupta V, ed. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(9):e0137306. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0137306

Berliner Senderey A, Kornitzer T, Lawrence G, et al. It’s how you say it: Systematic A/B testing of digital messaging cut hospital no-show rates. Ramagopalan SV, ed. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(6):e0234817. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234817

Mavandadi S, Ingram E, Klaus J, Oslin D. Social Ties and Suicidal Ideation Among Veterans Referred to a Primary Care–Mental Health Integration Program. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(9):824-832. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800451

Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M, Oxman AD, et al. A pragmatic–explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS): a tool to help trial designers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):464-475. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.12.011

Ford I, Norrie J. Pragmatic Trials. Drazen JM, Harrington DP, McMurray JJV, Ware JH, Woodcock J, eds. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(5):454–463. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1510059

Feyman Y, Legler A, Griffith KN. Appointment wait time data for primary & specialty care in veterans health administration facilities vs. community medical centers. Data Brief. 2021;36:107134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2021.107134

Greg Snow. blockrand: Randomization for Block Random Clinical Trials. Published online April 1, 2020. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/blockrand/blockrand.pdf

Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Tuepker A, Metcalf EE, Strange W, Teo AR. Applying user-centered design in the development of nudges for a pragmatic trial to reduce no-shows among veterans. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(6):1620-1627. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2021.10.024

Dongsheng Yang, Jarrod E. Dalton. A unified approach to measuring the effect size between two groups using SAS®. In: Statistics and Data Analysis. Vol 335. ; 2012. https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings12/335-2012.pdf

Zeileis A, Köll S, Graham N. Various Versatile Variances: An Object-Oriented Implementation of Clustered Covariances in R. J Stat Softw. 2020;95(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v095.i01

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. About VA disability ratings. https://www.va.gov/disability/about-disability-ratings/

Moore BJ, White S, Washington R, Coenen N, Elixhauser A. Identifying Increased Risk of Readmission and In-hospital Mortality Using Hospital Administrative Data: The AHRQ Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Med Care. 2017;55(7):698-705. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000735

US Department of Veterans Affairs. Care Assessment Needs (CAN) Primer. US Dept of Veterans Affairs; 2021.

Davies ML, Goffman RM, May JH, et al. Large-scale no-show patterns and distributions for clinic operational research. Healthc Basel Switz. 2016;4(1):15. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4010015

Bongaerts TH, Büchner FL, Middelkoop BJ, Guicherit OR, Numans ME. Determinants of (non-)attendance at the Dutch cancer screening programmes: A systematic review. J Med Screen. 2020;27(3):121-129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0969141319887996

Sparr LF, Moffitt MC, Ward MF. Missed psychiatric appointments: who returns and who stays away. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(5):801-805. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.150.5.801

Hanley JA, Negassa A, Edwardes MD deB, Forrester JE. Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: an orientation. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(4):364–375. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwf215

Hu FB, Goldberg J, Hedeker D, Flay BR, Pentz MA. Comparison of population-averaged and subject-specific approaches for analyzing repeated binary outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(7):694-703. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009511

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Published online 2020. https://www.R-project.org/

Saul B. smd: Compute Standardized Mean Differences. R package version 0.6.6. Published online 2020. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=smd

Zeileis A, Hothorn T. Diagnostic Checking in Regression Relationships. R News. 2002;2(3):7-10.

Zeileis A. Object-Oriented Computation of Sandwich Estimators. J Stat Softw. 2006;16(9). doi:https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v016.i09

Halekoh U, Højsgaard S, Yan J. The R Package geepack for Generalized Estimating Equations. J Stat Softw. 2006;15(2). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v015.i02

Yan J, Fine J. Estimating equations for association structures: ESTIMATING EQUATIONS FOR ASSOCIATION STRUCTURES. Stat Med. 2004;23(6):859-874. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1650

Yan J. geepack: Yet Another Package for Generalized Estimating Equations. R-News. 2002;2/3:12-14.

Mertens S, Herberz M, Hahnel UJJ, Brosch T. The effectiveness of nudging: A meta-analysis of choice architecture interventions across behavioral domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(1):e2107346118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2107346118

Maier M, Bartoš F, Stanley TD, Shanks DR, Harris AJL, Wagenmakers EJ. No evidence for nudging after adjusting for publication bias. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2022;119(31):e2200300119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2200300119

Trivedi RB, Post EP, Sun H, et al. Prevalence, Comorbidity, and Prognosis of Mental Health Among US Veterans. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):2564-2569. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302836

Teo AR, Metcalf EE, Strange W, et al. Enhancing Usability of Appointment Reminders: Qualitative Interviews of Patients Receiving Care in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(1):121-128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06183-5

Vlaev I, King D, Darzi A, Dolan P. Changing health behaviors using financial incentives: a review from behavioral economics. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1059. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7407-8

Brewster S, Bartholomew J, Holt RIG, Price H. Non-attendance at diabetes outpatient appointments: a systematic review. Diabet Med J Br Diabet Assoc. 2020;37(9):1427-1442. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14241

Nirenberg TD, Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Effective and inexpensive procedures for decreasing client attrition in an outpatient alcohol treatment program. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1980;7(1):73-82.

McFall M, Malte C, Fontana A, Rosenheck RA. Effects of an outreach intervention on use of mental health services by veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC. 2000;51(3):369-374. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.51.3.369

Comtois KA, Kerbrat AH, DeCou CR, et al. Effect of Augmenting Standard Care for Military Personnel With Brief Caring Text Messages for Suicide Prevention: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online February 13, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4530

Dolan P, Hallsworth M, Halpern D, King D, Metcalfe R, Vlaev I. Influencing behavior: The mindspace way. J Econ Psychol. 2012;33:264-277.

Gollwitzer P. Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. Am Psychol. 1999;54:493-503.

Fehr E, Schmidt K. A Theory of Fairness, Competition, and Cooperation. Q J Econ. 1999;114.

Andreoni J. Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. Econ J. 1990;100:464-477.

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported (or supported in part) by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Service (grant number IIR 17-134).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Teo, A.R., Niederhausen, M., Handley, R. et al. Using Nudges to Reduce Missed Appointments in Primary Care and Mental Health: a Pragmatic Trial. J GEN INTERN MED 38 (Suppl 3), 894–904 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08131-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08131-5