Abstract

Background

Engaging people experiencing homelessness or unstable housing in hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment is critical to achieving HCV elimination.

Objective

To describe HCV treatment outcomes, including factors associated with retention through the treatment cascade, for a cohort of individuals treated in a homeless health center in Boston.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Participants

All individuals who initiated HCV treatment with Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program’s HCV treatment program between January 2014 and March 2020 (N = 867).

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was sustained virologic response (SVR), defined as an HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) level ≤ 15 IU/mL at least 12 weeks after treatment completion. We used multivariable logistic regression to examine the association between baseline variables and SVR. Process-oriented outcomes included treatment completion, assessment for SVR, and achievement of SVR.

Results

Of 867 individuals who started HCV treatment, 796 (91.8%) completed treatment, 678 (78.2%) were assessed for SVR, and 607 (70.0%) achieved SVR. In adjusted analysis, residing in stable housing (OR 3.83, 95% CI 1.85–7.90) and age > 45 years old (OR 1.53, 95% CI 1.04–2.26) were associated with a greater likelihood of achieving SVR. Recent drug use (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.41–0.95) was associated with a lower likelihood of SVR. Age, housing status, and drug use status impacted retention at every step in the treatment cascade.

Conclusion

A large proportion of homeless-experienced individuals engaging in HCV treatment in a homeless health center achieved SVR, but enhanced approaches are needed to engage and retain younger individuals, those with recent or ongoing substance use, or those experiencing homelessness or unstable housing. Efforts to achieve HCV elimination in this population should consider the complex and overlapping challenges experienced by this population and aim to address the fundamental harm of homelessness itself.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

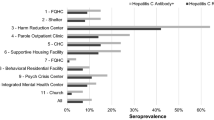

In the USA, the prevalence of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among people experiencing homelessness or unstable housing is estimated to be 12–31%, as compared to 1% in the general population.1–4 Among populations experiencing homelessness who inject drugs, the reported prevalence is as high as 70–78%.2, 3

With the advent of highly effective direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy for HCV, the World Health Organization (WHO) has established a goal of global HCV elimination by 2030.5 Diagnosis and treatment of 80% of the people living with HCV in the world will be required to meet this goal.6 The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) HCV Special Interest Group (SIG), in highlighting key elements on the pathway to HCV elimination, has recognized the need for innovative approaches to engage people who are homeless, who are unstably housed, and who inject drugs.7

Homelessness and unstable housing status have been associated with heightened vulnerability throughout the HCV care cascade8, including lower likelihood of initiating treatment1, 9–11 and completing treatment12 compared to housed cohorts and non-homeless cohorts of people who inject drugs. If individuals experiencing homelessness or unstable housing are successfully retained through the treatment course, prior studies describe sustained virologic response (SVR) rates that are comparable to those in housed populations.8, 13–16

The aim of this study is to assess factors associated with retention through the treatment cascade from treatment initiation to SVR achievement in a cohort of homeless-experienced individuals with a high burden of drug use. The findings of this study could inform efforts to successfully engage people with HCV who are experiencing homelessness and advance the WHO and AASLD goals for HCV elimination.

METHODS

Participants and Setting

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all individuals who initiated HCV treatment at Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program (BHCHP) between January 2014 and March 2020. BHCHP is a Federally Qualified Health Center that provides integrated primary care services via a patient-centered medical home approach to more than 11,000 individuals annually. BHCHP operates over 30 sites in greater Boston, including shelters, day centers, street and van outreach, and motels. According to internal data, all individuals seen at BHCHP are homeless-experienced, but approximately 16–20% have obtained housing and remain in care at BHCHP.

This study includes data on 300 participants whose HCV treatment outcomes in 2014-2017 were described in a prior report.14 This analysis expands upon that prior report by adding substantially more participants who have been treated since 2017, permitting updated SVR estimates in a broader population and improving the statistical power of inferential analyses.

HCV Care Model

The BHCHP Care to Cure HCV treatment team is based at the program’s largest site and was founded in January 2014 by non-specialist primary care clinicians with training in HCV treatment. It has since grown to include two non-clinician care coordinators (2.0 full-time equivalent [FTE]), a registered nurse (0.25 FTE), a data manager (0.33 FTE), a primary care nurse practitioner who serves as team director (0.2 FTE), and 10 primary care providers (MDs, NPs, and PAs).

There are no pre-screening or eligibility criteria for referral to the HCV team apart from an established HCV diagnosis. Referrals occur through various pathways, including patient self-referrals, BHCHP staff, and outside agencies and institutions like the local county jail. Additionally, direct linkage is facilitated by BHCHP’s HIV Counseling and Testing team that conducts infectious disease testing at residential treatment programs and on the street, with a particular engagement focus on people who inject drugs (PWID) and other high-risk individuals. Education sessions and signage at BHCHP sites and partner agencies promote awareness of HCV and treatment availability. Individuals are not required to receive primary care or other health services at BHCHP to be linked to the HCV treatment team.

The Care to Cure team follows a standardized intake assessment and treatment protocol, incorporating AASLD/Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) guidelines.17 Treatment readiness is based on adherence to appointments and is defined broadly. Abstinence from drugs and alcohol is not required to proceed with treatment. Efforts to retain individuals through the treatment process are largely provided by the care coordinators and nurse, who offer flexible support via weekly phone calls and texts, clinic visits, medication delivery and outreach, pillboxes, and directly observed therapy. Collaboration with other BHCHP teams to coordinate care across primary, behavioral health, and office-based addiction treatment services also supports retention in HCV treatment.

All baseline and outcome data were collected during routine clinical care using BHCHP’s electronic health record (EHR; Epic) as well as from the HCV team’s internal tracking system (Salesforce Health Cloud) and retrospectively extracted for analysis. Though some individuals were treated more than once during the study period, only first courses of treatment were included in this analysis. Data collection on the study sample continued through November 1, 2020, to include as much available outcome data as possible.

Baseline Variables

Demographic characteristics included age and self-reported gender identity, race, ethnicity, and preferred language. Age was dichotomized along the mean.

Housing status at intake was gathered using a standardized menu of options and dichotomized for analysis as homeless or unstably housed vs stably housed. Homeless or unstably housed was defined as a current usual nighttime residence of shelter, street, motel, doubled-up, or residential/transition treatment program, and/or experience of any of these housing statuses in the preceding year. Stable housing was defined as currently housed either in an independent (unsupported) setting or a supported setting, such as congregate housing with on-site case management, and with no experience of homelessness or unstable housing in the year prior to linkage to HCV treatment. We also collected self-reported history of incarceration in the year preceding linkage to the HCV team.

Substance use variables included self-reported use of drugs or “heavy” alcohol in the 6 months preceding linkage to the HCV team. Alcohol use was defined as “heavy” if the individual described their intake as more than “occasional” or “social,” and the nurse or provider probed for “heavy” use as appropriate. Special attention was paid to opioid use disorder (OUD) to assess the role of medication treatment for OUD (MOUD) in outcomes analysis. Active diagnosis of OUD was confirmed by the presence of an ICD-10 code for opioid use disorder (F11) or polysubstance use disorder (F19.1, F19.2, F19.9) in the EHR at the time of baseline assessment. Participation in MOUD was based on self-report of current medication treatment with buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone if it was being taken for OUD.

Baseline HIV status was based on the presence of a corresponding ICD-10 code (B20) in the EHR at the time of baseline assessment. Routine baseline HIV testing was incorporated into HCV treatment intake in 2019 but was practiced inconsistently prior to that point.

The source of HCV treatment referral was categorized as internal, HIV Counseling and Testing team, or external. Internal referrals were from a member of the patient’s care team. Referrals from the HIV Counseling and Testing team were made by a specific BHCHP team that focuses on outreach to individuals at heightened risk for infectious diseases and not otherwise connected to care at BHCHP. Referrals were categorized as external if they were not facilitated by BHCHP staff and included self-referrals or those coming from other agencies.

The primary risk factor for HCV acquisition was based on self-report and categorized as injection drug use–related, unknown, iatrogenic, sexual, or casual (such as intranasal drug use, blood contact not otherwise described). For purposes of analysis, the mode of acquisition was dichotomized as being related or unrelated to injection drug use.

Additional HCV-related characteristics included laboratory-measured HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) level and genotype, planned treatment regimen and duration (8 weeks or > 8 weeks), and Metavir stage of liver fibrosis based on the fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index,18 serum biomarkers, transient elastography, or clinical diagnosis. Fibrosis level was dichotomized for analysis as Metavir stage F4 vs all other stages (F0–F3 and indeterminate).

For all baseline variables, when EHR review did not permit a definitive classification of a particular variable, the variable’s value was recorded as “unknown.”

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was SVR, defined as an HCV RNA ≤ 15 IU/mL at least 12 weeks after treatment completion. Process-oriented outcomes included retention at key steps in the treatment cascade: completion of treatment, assessment for SVR, and achievement of SVR.

Data Analysis

Baseline measures were presented using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Among treatment initiators, we calculated the percentage of individuals who completed treatment and the percentage who returned for SVR. The proportion of individuals achieving SVR was calculated using the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle where all participants who started treatment were included in the denominator, with anyone lost to follow-up considered not to have achieved SVR. In a sensitivity analysis, we re-estimated the proportion who achieved SVR using a modified ITT (mITT) approach where participants who were not assessed for SVR were excluded from the denominator.

We used t tests and either chi-square tests or Fisher exact tests to examine the unadjusted associations between baseline variables and ITT SVR status. We then used logistic regression to fit a multivariable model of factors associated with achieving ITT SVR, with model variables selected based on unadjusted associations, a priori hypotheses, and previous research. For categorical variables, when < 1% of the cohort was represented by a single category, individuals in that category were excluded from analysis.

We conducted analyses in Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corp) and STATA 14.2 (Stata Corp). We used a two-tailed significance level of P < 0.05.

Human Subjects

The study protocol was approved by the Boston Medical Center Institutional Review Board and deemed to meet minimal risk criteria with a waiver of informed consent granted in light of the retrospective nature of the study. Individuals did not receive any payments for engaging in care with the HCV treatment team nor were they retroactively contacted by the study team for the purposes of data collection.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Eight hundred sixty-seven adults started a first course of treatment with the BHCHP Care to Cure HCV team between January 2014 and March 2020. Among those who started treatment, 47.4% were younger than 45 years old, 80.7% were male, 57.9% identified as white, and 22.3% identified as Hispanic (Table 1). At baseline, 84.1% of individuals self-reported experiencing homelessness or unstable housing within the past year.

Almost 90% of individuals identified injection drug use as the primary risk factor for HCV acquisition. The majority had a diagnosis of opioid use disorder (68.4%), of whom 75% were receiving MOUD at time of HCV treatment. The self-reported prevalences of any drug use or heavy alcohol use in the preceding 6 months were 45.2% and 15.7%, respectively.

Referrals to treatment largely originated from internal BHCHP staff, although 24% of individuals were referred by the HIV Counseling and Testing team.

Outcomes

Of the 867 individuals who started HCV treatment, 796 (91.8%) completed their prescribed medication course. A total of 678 (78.2%) were assessed for SVR, 33 of whom did not complete treatment. In total, 607 (70.0%) of 867 treatment initiators achieved SVR, including 3 treatment non-completers. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of HCV treatment outcomes. In the mITT assessment, 607 of the 678 with available SVR data achieved SVR, yielding a cure rate of 89.5%.

The percentages achieving SVR by baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Preferred language other than English or Spanish was excluded from the analysis (n = 3). The unadjusted odds of achieving SVR were higher among individuals who were older, Black/African American, Spanish-speaking, and stably housed, as well as those reporting recent heavy alcohol use, those with a diagnosis of HIV or cirrhosis, and those who received a regimen longer than 8 weeks. Lower odds of SVR were observed among individuals who were younger, who were English-speaking, or who reported recent drug use, recent homelessness or unstable housing, or recent incarceration, or who were referred by the HIV Counseling and Testing team or from an external source.

In adjusted analysis, many of these variables remained significant predictors of SVR (Table 2). Individuals older than 45 years old had higher odds of achieving SVR (OR 1.53, 95% CI 1.04–2.26), as did those reporting recent heavy alcohol use (OR 2.27, 95% CI 1.40–4.00). Stable housing was associated with 3.83 higher odds of achieving SVR (95% CI 1.85–7.90) compared to those with recent homelessness or unstable housing. Lower likelihood of achieving SVR was observed among individuals reporting recent drug use (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.41–0.95) and those referred by the HIV Counseling and Testing Team (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.29–0.73) or an external source (OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.14–0.53). Although past-year incarceration was significantly associated with SVR in unadjusted analysis, it was not included in the multivariable model because of the high proportion of missing data.

Process Outcomes

Of the characteristics described in the adjusted SVR analysis, age, recent drug use, and housing status were significantly associated with retention at every stage of the treatment cascade (Table 3). Younger individuals, those reporting recent drug use, and those experiencing homelessness or unstable housing were less likely to complete treatment, present for SVR, or achieve SVR, relative to their respective comparator groups. Conversely, differences in outcomes by alcohol use status appeared to be related solely to a lower likelihood of presenting for SVR assessment and not to differences in treatment completion or SVR achievement among those who obtained SVR labs.

DISCUSSION

In this 6-year retrospective cohort study of homeless-experienced individuals treated for HCV in a real-world community health center setting, 91.8% completed treatment and 70.0% achieved SVR, but a substantial proportion (21.8%) were not assessed for cure. Analysis of process measures as well as intention-to-treat outcomes further contextualize our findings and identify opportunities for intervention and improvement. To our knowledge, this is the largest evaluation of HCV treatment outcomes in this population since the advent of DAA therapy.

Individuals ≥ 45 years old had 50% higher odds of achieving SVR than younger individuals, and older age was associated with retention at every step in the treatment cascade. This is consistent with other real-world studies of HCV care for PWID across homeless and non-homeless cohorts. Older age has been associated with increased treatment uptake, decreased likelihood of loss to follow-up, and improved SVR outcomes.9, 19–21 Qualitative studies exploring HCV care and treatment experiences of younger PWID, and specifically those who are also experiencing homelessness, have identified numerous opportunities for improvement. One study from San Francisco found that individuals’ perceived barriers to engaging in care included lack of material resources such as housing and transportation as well as community stigma associated with having HCV.22 Stigma, particularly by medical providers, as well as feeling undeserving of treatment, were identified by young PWID in Boston as a major factor affecting their experience and motivation for HCV treatment.23 They additionally discussed ambivalence around engaging in treatment at all.23. Improving the disparity in SVR outcomes for young PWID experiencing homelessness will require tailored approaches that address their tangible needs and counter the ambivalence they describe.

Individuals with documented heavy alcohol use appeared more than twice as likely to achieve SVR. This surprising finding solely reflects an increased likelihood of presenting for SVR among this group. It is possible that individuals who felt comfortable disclosing their alcohol use did so because of other factors, such as trusting care relationships, which also served to support their retention in HCV care. For example, one BHCHP primary care team that has long-established care relationships with a street-homeless cohort with a high burden of alcohol use proactively collaborated with the HCV team to prioritize and support HCV treatment for their patients. This type of collaboration, which entailed training and empowering those street-based providers to do the HCV evaluations with the HCV team providing clinical and systems-navigation support in the background, presents a highly effective way to engage and retain individuals who may otherwise be at high risk for loss to follow-up.

Recent drug use was associated with a lower likelihood of achieving SVR. This impacted retention through every step in the treatment cascade. Ultimately, 59.4% of homeless-experienced individuals reporting recent drug use achieved SVR. One possible explanation for our findings is that they are the reflection of the relatively high proportion of individuals who were not retained to SVR assessment. The BHCHP HCV treatment team receives a large number of referrals from residential treatment programs and syringe exchange programs serving people with current or recent histories of drug use, but BHCHP does not routinely operate clinical services in those programs. Individuals from those settings often have fewer connections to BHCHP services and less collateral support to prevent loss to follow-up.

The overlapping and synergistic stressors associated with homelessness and drug use understandably present challenges to HCV treatment. We feel strongly, however, that this complexity should not preclude access to treatment. Rather, we suspect that improved outcomes for people with recent drug use could be achieved through further decentralization of HCV treatment services and integration into care systems with which PWID are most likely to remain engaged, leveraging established relationships with trusted providers and staff to promote treatment success and prevention of reinfection.

Stable housing was associated with an almost fourfold higher likelihood of achieving SVR compared to those experiencing homelessness or unstable housing. Stable housing impacted retention throughout the treatment cascade, but most notably at the point of SVR assessment. Efforts to improve this disparity could include bringing care closer to where people live and sleep, such as in shelters, drop-in centers, and on the street, or more closely integrated with existing care relationships like methadone maintenance programs or syringe service sites. Interventions targeting the social determinants of health, including transportation assistance and other tangible incentives for returning for SVR, should be employed to improve retention and treatment outcomes in the near term.

Recent innovations in the HCV field could further support retention and treatment success for people experiencing homelessness or unstable housing. Shifting from SVR assessment 12 weeks post-treatment completion to four would likely improve retention. Concordance between SVR4 and SVR12 has been increasingly well-established in the literature, and it may now be appropriate to reevaluate the role for shorter-interval SVR confirmation.24–26 Although not yet available in North America, point-of-care RNA testing could also be a useful tool in non-traditional outreach settings where access to conventional lab testing is limited.

It is likely, however, that homelessness and unstable housing will remain a substantial barrier to successful treatment at the individual level and to HCV elimination at the population level. Efforts targeting housing and other social determinants of health should be considered as critical to HCV elimination goals. Hepatology, infectious disease, and community HCV-treating providers have previously demonstrated a willingness to consider the broader health needs and policy issues affecting people living with, or at risk for, HCV including leveraging their influence to specifically advocate for HCV treatment access for PWID, and harm reduction services to reduce HCV transmission.7, 17 Willingness to engage in similar housing-oriented advocacy may be essential to achieving elimination in this highly marginalized population.

Limitations

Our findings are subject to limitations. Data were collected from an EHR and are subject to the shortcomings inherent in clinically captured data, including variability in documentation practices and other factors that may lead to incomplete or inaccurate information. Supervision from a clinical expert and review by study staff of a random sample of charts helped to ensure the accuracy of the abstracted data. Additionally, self-reported data is always subject to bias. It is possible that individuals may not have felt comfortable disclosing certain information around stigmatized topics, such as drug, alcohol use, and incarceration history. This may have contributed to underreporting or overestimation of certain characteristics.

These findings reflect clinical work that occurred from 2014 to 2020. Many real-world factors, including HCV treatment recommendations and guidelines, processes and restrictions around treatment access, and our program’s own growth evolved substantially during that time. Analysis of any potential era effect on the study outcomes was beyond the scope of this evaluation. Additionally, the observational nature of the study limits causal inference around the predictors of SVR due to the possibility of residual confounding by unknown or unmeasured variables. Finally, this study took place at a large, urban homeless health care program in a state with universal health insurance and no requirements for abstinence before treatment. Because of this, our results may not be generalizable to other settings with different health policy environments.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that an HCV treatment program integrated within a homeless health center can successfully engage, retain, and achieve SVR in a large proportion of homeless-experienced individuals. While enhanced outreach and support for this marginalized group should be implemented in the near term, longer-term efforts to achieve HCV elimination should aim to address the fundamental harm of homelessness itself.

Data Sharing

Owing to the marginalized status of the study population, the dataset created and used for this analysis is not available for sharing.

References

Noska AJ, Belperio PS, Loomis TP, O'Toole TP, Backus LI. Engagement in the hepatitis C care cascade among homeless veterans, 2015. Public Health Rep. 2017;132(2):136-139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354916689610.

Gelberg L, Robertson MJ, Arangua L, et al. Prevalence, distribution, and correlates of hepatitis C virus infection among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Public Health Rep. 2012;127(4):407-21.

Strehlow AJ, Robertson MJ, Zerger S, et al. Hepatitis C among clients of health care for the homeless primary care clinics. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(2):811-33. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2012.0047.

Hofmeister MG, Rosenthal EM, Barker LK, et al. Estimating prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 2013-2016. Hepatology. 2019;69(3):1020-1031. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.30297.

World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report 2017. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/255016.

World Health Organization. Guidelines for the care and treatment of persons diagnosed with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550345; July 2018.

Feld JJ, Ward JW. Key Elements on the pathway to HCV elimination: lessons learned from the AASLD HCV Special Interest Group 2020. Hepatol Commun. 2021;5(6):911-922. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.1731.

Hashim A, Macken L, Jones A, McGeer M, Aithal G, Verma S. Community-based assessment and treatment of hepatitis C virus-related liver disease, injecting drug and alcohol use amongst people who are homeless: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;96:103342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103342.

Corcorran MA, Tsui JI, Scott JD, Dombrowski JC, Glick SN. Age and gender-specific hepatitis C continuum of care and predictors of direct acting antiviral treatment among persons who inject drugs in Seattle, Washington. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;220:108525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108525.

Falade-Nwulia O, Sacamano P, McCormick SD, et al. Individual and network factors associated with HCV treatment uptake among people who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;78:102714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102714.

Valerio H, Alavi M, Silk D, et al. Progress towards elimination of hepatitis C infection among people who inject drugs in Australia: The ETHOS Engage Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa571.

Ziff J, Vu T, Dvir D, et al. Predictors of hepatitis C treatment outcomes in a harm reduction-focused primary care program in New York City. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18(1):38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-021-00486-4.

Hodges J, Reyes J, Campbell J, Klein W, Wurcel A. Successful implementation of a shared medical appointment model for hepatitis C treatment at a community health center. J Community Health. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-018-0568-z.

Beiser ME, Smith K, Ingemi M, Mulligan E, Baggett TP. Hepatitis C treatment outcomes among homeless-experienced individuals at a community health centre in Boston. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;72:129-137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.03.017.

Read P, Gilliver R, Kearley J, et al. Treatment adherence and support for people who inject drugs taking direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C infection. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26(11):1301-1310. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.13175.

Harney BL, Whitton B, Lim C, et al. Quantitative evaluation of an integrated nurse model of care providing hepatitis C treatment to people attending homeless services in Melbourne, Australia. Int J Drug Policy. 2019.

AASLD-IDSA. HCV testing and linkage to care. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. http://www.hcvguidelines.org.

Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Nalpas B, et al. FIB-4: an inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV infection. Comparison with liver biopsy and fibrotest. Hepatology. 2007;46(1):32-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.21669.

Darvishian M, Wong S, Binka M, et al. Loss to follow-up: a significant barrier in the treatment cascade with direct-acting therapies. J Viral Hepat. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.13228.

Hajarizadeh B, Cunningham EB, Reid H, Law M, Dore GJ, Grebely J. Direct-acting antiviral treatment for hepatitis C among people who use or inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(11):754-767. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30304-2.

Litwin AH, Lum PJ, Taylor LE, et al. A multisite randomized pragmatic trial of patient-centered models of hepatitis C treatment for people who inject drugs: the HERO Study - Hepatitis C Real Options 2020.

Morris MD, Mirzazadeh A, Evans JL, et al. Treatment cascade for hepatitis C virus in young adult people who inject drugs in San Francisco: low number treated. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;198:133-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.02.008.

Skeer MR, Ladin K, Wilkins LE, Landy DM, Stopka TJ. ‘Hep C’s like the common cold’: understanding barriers along the HCV care continuum among young people who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;190:246-254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.013.

Burgess SV, Hussaini T, Yoshida EM. Concordance of sustained virologic response at weeks 4, 12 and 24 post-treatment of hepatitis c in the era of new oral direct-acting antivirals: a concise review. Ann Hepatol. 2016;15(2):154-9. https://doi.org/10.5604/16652681.1193693.

Yoshida EM, Sulkowski MS, Gane EJ, et al. Concordance of sustained virological response 4, 12, and 24 weeks post-treatment with sofosbuvir-containing regimens for hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2015;61(1):41-5. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27366.

Sulkowski M, Feld J, Reau N, et al. Concordance between SVR4, SVR12, and SVR24 in HCV-infected. Patients who received fixed-dose combination sofosbuvir/velpatasvir in phase 3 clinical trials. Poster presented at: International Liver Congress; June 23-26, 2021 2021; virtual. Accessed 6/29/22.

Acknowledgements

Contributors: We thank Elizabeth Lewis, MBA, for her input on the statistical analysis.

Funding

Dr. Baggett is supported by the Massachusetts General Hospital Research Scholars Program. Dr. Baggett receives royalty payments from UpToDate for authorship of a topic review on the health care of homeless people in the USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations: Preliminary findings were shared at the International Network on Health and Hepatitis in Substance Users Conference 2021, virtual.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Beiser, M.E., Shaw, L.C., Wilson, G.A. et al. Factors Associated with Sustained Virologic Response to Hepatitis C Treatment in a Homeless-Experienced Cohort in Boston, 2014–2020. J GEN INTERN MED 38, 865–872 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07778-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07778-w