Abstract

Background

Residency program directors will likely emphasize the United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) Step 2 clinical knowledge (CK) exam more during residency application given the recent USMLE Step 1 transition to pass/fail scoring. We examined how internal medicine clerkship characteristics and NBME subject exam scores affect USMLE Step 2 CK performance.

Design

The authors used univariable and multivariable generalized estimating equations to determine associations between Step 2 CK performance and internal medicine clerkship characteristics and NBME subject exams. The sample had 21,280 examinees’ first Step 2 CK scores for analysis.

Results

On multivariable analysis, Step 1 performance (standardized β = 0.45, p < .001) and NBME medicine subject exam performance (standardized β = 0.40, p < .001) accounted for approximately 60% of the variance in Step 2 CK performance. Students who completed the internal medicine clerkship last in the academic year scored lower on Step 2 CK (Mdiff = −3.17 p < .001). Students who had a criterion score for passing the NBME medicine subject exam scored higher on Step 2 CK (Mdiff = 1.10, p = .03). There was no association between Step 2 CK performance and other internal medicine clerkship characteristics (all p > 0.05) nor with the total NBME subject exams completed (β=0.05, p = .78).

Conclusion

Despite similarities between NBME subject exams and Step 2 CK, the authors did not identify improved Step 2 CK performance for students who had more NBME subject exams. The lack of association of Step 2 CK performance with many internal medicine clerkship characteristics and more NBME subject exams has implications for future clerkship structure and summative assessment. The improved Step 2 CK performance in students that completed their internal medicine clerkship earlier warrants further study given the anticipated increase in emphasis on Step 2 CK.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

On February 12, 2020, the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) and the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) announced that the United States Medical License Exam (USMLE) Step 1 (subsequently referred to as Step 1) will become a pass/fail exam.1 One likely consequence of this change is a greater emphasis on USMLE Step 2 Clinical Knowledge (subsequently referred to as Step 2 CK) performance by residency program directors in selecting applicants to interview and in subsequent ranking of applicants.2–6 As such, there may be increased interest among medical schools in identifying clerkship characteristics that can improve performance on Step 2 CK. While numerous studies have identified an association between Step 2 CK performance and Step 1 performance as well as NBME subject exam performance, few studies examine potential associations between Step 2 CK performance and specific clerkship characteristics (e.g., clerkship length, clerkship start month, presence of ambulatory clinical experience).7–12 While internal medicine clerkship characteristics differ across medical schools,13, 14 there are no multi-institutional studies examining the effects of these specific characteristics on Step 2 CK performance. Prior studies examining the association between clerkship characteristics and Step 2 CK have focused on significant global curricular changes across all clerkships.15–19 In addition, many medical schools in the USA have restructured their curriculum to shorten the length of the pre-clerkship phase, reducing it to 18 or even 12 months.20, 21 This change has led some students to begin their clerkships earlier than the traditional July start date. Given these changes, the timing of the Step 1 and Step 2 CK exams in relation to the core clinical clerkships (either before or after) has gained increasing importance. One recent study found no meaningful difference in Step 2 CK scores regardless of whether Step 1 was taken before or after clinical clerkships.22 Prior studies have focused exclusively on the association of a shortened preclinical time with Step 1 and Step 2 CK performance with little consideration of specific clerkship characteristics or timing of certain clerkships in the year.23 In addition, despite increased use of NBME subject exams in most clerkships,13 data on how exam utilization (particularly the number of NBME subject exams administered) affects Step 2 CK performance is limited.24 Given the paucity of data, our large multi-institutional study aims to answer the following questions1: What is the association between internal medicine clerkship characteristics and Step 2 CK performance after controlling for Step 1 and NBME medicine subject exam scores?2 What is the association between Step 2 CK scores and clerkship start dates?3 What is the association between Step 2 CK scores and the number of NBME subject exams administered in core clerkships? Given our previous work examining the association between IM clerkship characteristics and NBME medicine subject exam performance, we hypothesize the following1: There will be few, if any, internal medicine clerkship characteristics associated with Step 2 CK performance.2 There will be a positive association between Step 2 CK performance and earlier clerkship start dates.3 There may be a positive correlation between Step 2 CK performance and the number of NBME subject exams a student completed.

Methods

Participants

We recruited internal medicine clerkship directors to participate in our study at the 2014 National Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine (CDIM) meeting and by phone call over a 10-month period from September 2014 through June 2015. We chose to include data from the most recent academic years at the time of recruitment (2011–2015). Participating clerkship directors obtained institutional review board approval or exemption for our study from their respective institutions. They confirmed the data and provided the NBME with their internal medicine clerkship characteristics, and the NBME matched examinees’ medicine subject exam scores and Step 2 CK scores with their corresponding schools. Subsequently, the NBME provided the first author (MMF) with a completely de-identified dataset for analysis.

Study Design

The CDIM-NBME Study Group, a combination of internal medicine clerkship directors and NBME members, designed this study (all authors are members of this study group). We analyzed data from 21,280 examinees from 62 LCME-accredited medical schools spanning 3 academic years, 2011–2014, whose students had their first Step 2 CK score available for analysis and took the NBME medicine subject exam before taking Step 2 CK. The students’ Step 2 CK results were available from 2011 to 2015. We confirmed clerkship characteristics with in-person interviews, phone calls, and follow-up emails to the participating clerkship directors over a 12-month period from 2014 to 2015.

Clerkship Characteristics

Clerkship characteristics were defined using terminology from prior research related to NBME subject exam performance.13 We defined a longitudinal student as a medical student who participated in the care of a cohort of patients over time and continued following these patients to achieve clinical competence across multiple specialties in addition to internal medicine. Academic start month was the first month of any clinical clerkships at a particular school. Clerkship length was the duration of the internal medicine clerkship in weeks. Having an ambulatory clinical experience entailed participating in outpatient clinical care during the internal medicine clerkship; we further refined this variable to be either a structured block format distinct from the inpatient experience (ambulatory clinical experience = yes) or integrated into the inpatient experience (ambulatory clinical experience = mixed). A study day was the presence of one or more days after clinical responsibilities ended but before the subject exam. A combined clerkship included at least one other specialty (e.g., emergency medicine or neurology) in addition to internal medicine. A pass-cutoff designated a school’s use of any criterion score on the medicine subject exam to ensure a passing grade if a student completed the other clerkship requirements. An honors-cutoff designated a school’s use of any criterion score on the medicine subject exam required to receive an honors grade.

A pre-clerkship curriculum was described as traditional (i.e., discipline-specific basic science subjects), organ-based (i.e., centered around body systems such as pulmonary or cardiology with integrated anatomical, physiological, and pathological processes), or hybrid (i.e., a mix of the 2 preceding models); a curriculum not clearly described was other. Quarter indicated the timing of the medicine subject exam during the academic year. For students in a non-traditional academic year, the first quarter comprised medicine subject exam test dates from May through July; the second quarter from August through October; the third quarter from November through January; and the fourth quarter comprised test dates from February through April. Conversely, for students in a traditional academic year, the first quarter comprised medicine subject exam test dates from July through September; the second quarter from October through December; the third quarter from January through March; and the fourth quarter comprised test dates from April through June.

The number of didactic hours was the number of hours within the internal medicine clerkship dedicated to the delivery of the formal curriculum, including lectures and case discussions. Finally, the number of NBME clinical subject exams was the total number of summative NBME clinical science subject exams a student completed in the core clinical clerkships.

Statistical Analysis

We list the number of examinees for each nominal and ordinal clerkship characteristic as valid counts and proportions, and we describe continuous covariates using medians with interquartile range (IQR) for the number of NBME clinical subject exams used and mean with standard deviation (SD) for the number of didactic hours, Step 1 score, and medicine subject exam score.

We used univariable and multivariable generalized estimating equations (GEE models) to estimate the average Step 2 CK performance as a function of all clerkship characteristics noted above as well as the number of NBME subject exams used, number of didactic hours, Step 1 performance, and medicine subject exam performance. As noted in Fitz et al.,13 most examinees (> 80%) were in either an 8-week or a 12-week clerkship. Therefore, we treated clerkship length as a nominal (rather than quantitative) explanatory variable; sensitivity analyses treating clerkship length as quantitative (rather than nominal) did not affect study conclusions. In our regression models, we specified a normal distribution with identity link for Step 2 performance and used empirical (robust) standard errors to account for the correlation within medical schools.25 We used linear regression models to estimate the coefficient of determination and standardized beta coefficients for Step 1 and NBME medicine subject exam performance. Regarding model assumptions, we used residual plots and QQ plots to assess linearity and normality, respectively. Variance inflation factors and tolerance statistics were used to monitor collinearity among the covariates included in the multivariable model.

Finally, sensitivity analyses assessed whether the academic start month moderated the association between clerkship length and Step 2 CK performance. Because this interaction term was not statistically significant in both our univariable and multivariable analyses, we removed it from the model. Like our prior publication,13 we provide stratified summary Step 2 CK performance statistics for each clerkship characteristic by examinees’ academic start month as supplemental digital content. We used SAS version 9.4 (Cary, North Carolina) for all analyses.26

Results

Clerkship Characteristics

As reported in Fitz et al.,13 there were 24,542 examinees included in the study. Among these individuals, 21,280 (87%) had their first Step 2 CK score available for the analysis and took the NBME medicine subject exam before taking Step 2 CK. Most of these examinees were in 8-week (9,057; 42.9%) or 12-week (8486; 39.9%) clerkships. About 5.6% (1,191) were enrolled in a 6-week clerkship, which was the shortest clerkship length in the study. Some examinees were enrolled in 9-week (370; 1.7%), 10-week (1,117; 5.3%), or 11-week (502; 2.4%) clerkships. Only 390 examinees (1.9%) were enrolled in a longitudinal clerkship. Most examinees began their clerkships in July (14,711; 69.1%) with the remainder starting in May (4,133; 19.4%), June (2,288; 10.8%), or January (148; 0.7%).

Approximately half of the examinees were from schools with no ambulatory clinical experience (10,262; 48.2%) during the internal medicine clerkship, while the remainder were from schools that used an ambulatory block format distinct from the inpatient experience (10,172; 47.8%); only 4.0% (846) had an integrated inpatient and ambulatory format. Approximately 13% (2,765) of examinees were in a combined clerkship (e.g., a clerkship that combined emergency medicine or neurology with internal medicine), and the majority (11,636; 54.7%) received a study day.

Nearly all (18,849; 88.8%) were enrolled in a school that required a minimum score on the medicine subject exam to pass the internal medicine clerkship. For most examinees (17,655; 83.0%), their school also required students achieve a certain score on the medicine subject exam to receive an honors grade in the internal medicine clerkship. Fewer than half of examinees (8,491; 39.9%) had a traditional pre-clerkship curriculum, while another 14.5% (3,079) had an organ-based curriculum; approximately 17.7% (3,755) had a hybrid curriculum, while the remaining 28.0% were in some other pre-clerkship curriculum. The median number of NBME clinical subject exams used was 6.00 (IQR: 5–7), and examinees received an average of 31.18 (SD = 16.42) didactic hours of education during the internal medicine clerkship. The average Step 1 score was 228.36 (SD = 20.31). The medicine subject exam score is a scaled score (μ = 70, SD = 8) and the mean was 78.60 (SD = 7.92). See Table 1 for the complete clerkship characteristics.

Analysis

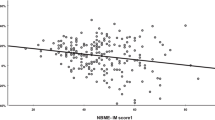

There was no association between Step 2 CK performance and clerkship length on univariable analysis (overall p = .27; Figure 1) or multivariable analysis (overall p = .21). A sensitivity analysis treating clerkship length as quantitative (rather than nominal) resulted in similar conclusions on univariable (p = .28) and multivariable analysis (p =.44). There was also no association between the count of NBME clinical subject exams and Step 2 CK performance on univariable (p = .25) or multivariable (p = .78) analysis (Table 2).

Controlling for all other covariates, students who took the medicine subject exam in the later quarter scored lower on the Step 2 CK (overall p < .001; Figure 1). Conversely, students at schools requiring a criterion score for passing the medicine subject exam scored nominally higher on the Step 2 CK examination (Mdiff = 1.10, 95% CI: 0.11 to 2.09; p = .03). Every 10-point increase in Step 1 performance was associated with a 3.85 (95% CI: 3.71 to 3.99; p < .001) point increase in Step 2 CK performance, and every 5-point increase in the medicine subject exam score was associated with a 4.65 (95% CI: 4.48 to 4.82; p < .001) point increase in Step 2 CK performance. Figure 2 shows the unadjusted slopes for these comparisons. Together, these two variables accounted for approximately 60% of the variability in Step 2 CK performance. In fact, as standardized regression coefficients, each standard deviation increase in Step 1 performance was associated with a 0.45 standard deviation increase in Step 2 CK performance. Similarly, a standard deviation increase in medicine subject exam performance was associated with a 0.40 standard deviation increase in Step 2 CK performance.

Students’ scores on Step 2 CK was generally comparable for all clerkship lengths regardless of whether they began in May (overall p = .18), June (overall p = .54), or July (overall p = .37); everyone beginning their clerkship in January was enrolled in a 12–20-week clerkship.

Stratified summary statistics for each clerkship characteristic by academic start month are available as supplemental content. Figure 1 shows that for students in July (first month of the traditional curriculum) (supplemental Table 1), Step 2 CK performance was lowest for students in a 6-week clerkship (M = 235.28, SD = 19.35) and comparable for students in an 8–11-week (M = 240.38, SD = 17.78) or 12–20-week clerkship (M = 240.37, SD = 17.80). For students in May (first month of the non-traditional curriculum) (supplemental Table 2), Step 2 CK performance was comparable for students in a 6-week clerkship (M = 240.01, SD = 16.15) and 8–11-week clerkship (M = 240.40, SD = 18.00) and was highest for those in a 12–20-week clerkship (M = 246.55, SD = 16.94). For students in June (supplemental Table 3), no student was enrolled in a 6-week clerkship and Step 2 CK performance was comparable for students in an 8–11-week clerkship (M = 238.70, SD = 17.82) or 12–20-week clerkship (M = 237.98, SD = 19.60).

Discussion

Given the recent United States Medical License Exam (USMLE) Step 1 transition to pass/fail, internal medicine residency program directors will likely place greater emphasis on the USMLE Step 2 Clinical Knowledge (CK) exam during applicant evaluation. We sought to understand whether internal medicine clerkship characteristics, clerkship start dates, and NBME subject exams are associated with USMLE Step 2 CK performance. After controlling for Step 1 and NBME medicine subject exam scores, our 62 center multi-institutional study of over 20,000 students did not reveal differences in Step 2 CK exam performance across many internal medicine clerkship characteristics, clerkship start dates, and summative number of NBME clinical subject exams. Our findings confirm those of previous studies regarding the predictive value of Step 1 and NBME subject exam scores on Step 2 CK performance.(8, 22, 23)

One of the most surprising findings from our study is the lack of association between the number of NBME subject exams a student has taken and subsequent performance on Step 2 CK. This finding is surprising because the NBME subject exams are similar in content and structure as the Step 2 CK exams. One possible explanation is that students are using more supplemental self-assessment exams,27 third-party examination questions, or devoting more independent study time to prepare for Step 2 CK regardless of the number of NBME subject exams a school administers. This finding should be reassuring to clerkship directors and schools that do not administer summative NBME subject exams for all of their clerkships in that their students are not disadvantaged for having fewer NBME subject exams. Furthermore, our finding that students are not disadvantaged on Step 2 CK by taking fewer NBME subject exams encourages the creation of innovative assessments in schools and their clerkships, including competency-based assessments. For example, clinical reasoning assessment and long-term retention of medical knowledge are popular trends in medical education,13 and the medical education community can be reassured that creative approaches to assessment do not disadvantage students’ performance on Step 2 CK. Additionally, many clerkships are exploring assessments of other competencies beyond medical knowledge, and this finding gives schools even greater latitude and freedom to development these new assessments.

Another unexpected finding was a small but statistically significant decrease in Step 2 CK scores among students who completed their internal medicine clerkship later in the academic year (quarters 3 and 4 versus quarters 1 and 2). The average score difference for students completing their internal medicine clerkship later in the academic year was 2–3 points lower, which is not meaningful for the vast majority of students given that this represents only ~0.10–0.16 SD, a small effect size. However, one could argue that it is relevant for those students who may be close to passing the Step 2 CK exam, as failing can have a profound impact on residency interviews and the subsequent National Resident Matching Program match.2

Given limitations of observational studies, we cannot explicitly determine why Step 2 CK scores are lower for students who completed their internal medicine clerkship later in the academic year. It is possible that early completion of the internal medicine clerkship provides a broader foundation, enabling students to further build on their existing knowledge with subsequent specialty experiences in a way that would not be possible when completing the internal medicine clerkship later in the year. Similarly, given that 50–60% of the Step 2 CK content is internal medicine,28 it is possible that students that complete their internal medicine clerkship (and thus the NBME medicine subject exam) early in the year would subsequently revisit this content for a second time to study for Step 2 CK. Conversely, students that complete their internal medicine clerkship later in the academic year may consolidate their NBME review with Step 2 CK preparation over a shorter period of time resulting in reduced familiarity with the material.

While we hypothesized that an earlier start date may be associated with increased clinical experience and increased consolidation of clinical knowledge being tested on Step 2 CK, we found that students who started their core clerkships in May or June did not have any difference in Step 2 CK performance compared to students with a traditional start date (i.e., July). This is important as several schools have subsequently transitioned to a pre-clerkship curriculum that spans 12 to 18 months.13, 14 Our study did not capture data from these curricular changes, but it is possible that the effects of internal medicine clerkship length are masked in our study because of the very large sample of examinees from schools with the traditional 2-year pre-clinical curriculum. As more schools transition to a shortened pre-clerkship curriculum, it will be important to monitor and study the effects of these changes on future medicine subject exams and Step 2 performance.

Despite the suggested benefits of increased integration of clinical frameworks into the pre-clerkship curriculum,29 students at schools with an organ-based or hybrid pre-clerkship curriculum performed similarly on Step 2 CK compared to their peers at schools with a traditional pre-clerkship curriculum format. We acknowledge that classifying the pre-clerkship curriculum at every school was challenging, and more than a quarter of the schools we studied did not fit into our category scheme. It is possible that this lack of difference may reflect a mismatch between curricula and assessment; the examination also may not capture the incremental benefits of an integrated pre-clerkship curricula or that differences in curricula may have relatively little impact on Step 2 CK performance.

Our study has multiple limitations. First, while Step 2 CK includes content derived from multiple clerkships, our Internal Medicine Clerkship Director study group only evaluated the association between Step 2 CK performance and internal medicine clerkship characteristics. Upon review of the Step 2 CK content, the outline identifies that medicine accounts for 50–60% of the exam28; thus, we felt justified only examining internal medicine clerkship characteristics. It is plausible that variables within other clerkships outside of internal medicine may have an effect on Step 2 CK performance. Future directions will include examining characteristics of all core clinical clerkships. Second, all the included schools were U.S. LCME-accredited medical schools, so our findings may not be applicable to osteopathic or international medical schools. Third, our data were from the 2011–2014 academic years. While the Step 2 CK framework and content have been consistent, internal medicine clerkship characteristics may have changed, and other clerkship characteristics may affect the interactions among the curricula, training environment, and students’ Step 2 CK performance. However, our large study had a similar representative distribution of internal medicine clerkship variables across the included schools as did other studies of survey data from the Association of American Medical Colleges, CDIM, and NBME during our study period.

In conclusion, our multi-institutional study did not reveal differences in Step 2 CK exam performance across many internal medicine clerkship characteristics, clerkship start dates, and summative number of NBME subject exams, after controlling for Step 1 and NBME medicine subject exam scores. The lack of association of Step 2 CK performance with many internal medicine clerkship characteristics and more NBME subject exams has implications for future internal medicine clerkship structure and summative assessment.

Additional Authors

Individuals meeting the criteria for authorship who are not listed individually in the byline but included in the CDIM-NBME Express Study Group include the following: Amanda Raff, MD, Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Bruce Houghton, MD, Creighton University. Jennifer Foster, MD, Florida Atlantic University. Janet Fitzpatrick, MD, Drexel University College of Medicine. Ryan Nall, MD, University of Florida. Jonathan Appelbaum, MD, Florida State University College of Medicine. Amber Pincavage, University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine. Cindy J Lai, MD, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco. Cyril Grum, MD, University of Michigan Medical School. Anna Donovan, MD, University of Pittsburgh. Viju John, MD, MS Rush University School of Medicine. Laura Zakowski, MD, University of Wisconsin School of Public Health. Stuart Kiken, MD, Rosalind Franklin College of Medicine. Chayan Chakraborti, MD, Tulane University School of Medicine. Doug Paauw, MD, University of Washington. Reeni Abraham, MD, and Blake Barker, MD, University of Texas Southwestern Medical School. Horatio Holzer, MD, Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai. Marti Hlafka, MD, Southern Illinois School of Medicine. Nina Mingioni, MD, Thomas Jefferson University Sidney Kimmel Medical College. Cynthia Burns, MD, Wake Forest School of Medicine. Winter Williams, MD, UAB Heersink School of Medicine. Chad Miller, MD, St. Louis University School of Medicine. Gauri Agarwal, MD, Miami Miller School of Medicine. Katie Lappé, MD, University of Utah School of Medicine. Deepti Rao, MD, University of New Mexico School of Medicine. William Kelly, MD, Uniformed Services University.

References

United States Medical Licensing Examination. InCUS—Invitational Conference on USMLE Scoring. Change to pass/fail score reporting for Step 1https://www.usmle.org/incus/#decision. Published February 12, 2020. Last Accessed February 18, 2021

National Residency Matching Program. Results of the 2020 NRMP Program Director Survey. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/2020-PD-Survey.pdf. Published June 2020. Last Accessed February 19, 2021.

National Residency Matching Program. Results of the 2018 NRMP Program Director Survey. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-2018-Program-Director-Survey-for-WWW.pdf. Published June 2018. Accessed February 19, 2021.

National Residency Matching Program. Results of the 2012 NRMP Program Director Survey.http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/programresultsbyspecialty2012.pdf. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/programresultsbyspecialty2012.pdf Published August 2012. Last Accessed February 19, 2021.

Willett, L. The Impact of a Pass/Fail Step 1 – A Residency Program Director’s View. Perspective. New England J Med, 2020

McDade W, Vela MB, Sánchez, JP. Anticipating the Impact of the USMLE Step 1 Pass/Fail Scoring Decision on Underrepresented-in-Medicine Students. Acad Med: 2020;95(9):1318-1321. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003490.

Rubright JD, Jodoin M, Barone MA. Examining Demographics, Prior Academic Performance, and United States Medical Licensing Examination Scores. Acad Med: 2019;94(3):364-370. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002366

Zahn CM, Saguil A, Artino AR Jr, et al. Correlation of National Board of Medical Examiners scores with United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 And Step 2 scores. Acad Med. 2012;87(10):1348-1354. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826a13bd

Hampton HL, Collins BJ, Perry KG, Meydrech EF, Wiser WL, Morrison JC. Order of rotation in third-year clerkships: Influence on academic performance. J Reprod Med. 1996;41;337-340.

Baciewicz FA, Arent L, Weaver M, Yeastings R, Thomford NR. Influence of clerkship structure and timing on individual student performance. Amer J Surg. 1990;159:265-268. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80277-6

Ripkey DR, Case SM, Swanson DB. Predicting performances on the NBME Surgery Subject Test and Step 2 CK: The effects of surgery clerkship timing and length. Acad Med. 1997;72:S31-S33. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199710001-00011.

Dong T, Copeland A, Gangidine M, Schreiber-Gregory D, Ritter EM, Durning SJ Factors Associated With Surgery Clerkship Performance and Subsequent Step Scores. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(5):1200-1205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.02.017

Fitz MM, Adams W, Haist SA, et al. Which Internal Medicine Clerkship Characteristics Are Associated With Students’ Performance on the NBME Medicine Subject Exam? A Multi-Institutional Analysis Acad Med. 2020;95(9):1404-1410. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003322

Pincavage AT, Fagan MJ, Osman NY, et al. A National Survey of Undergraduate Clinical Education in Internal Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(5):699-704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04892-0

Daniel M, Fleming A, Grochowski CO, et al. Why Not Wait? Eight Institutions Share Their Experiences Moving United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 After Core Clinical Clerkships. Acad Med. 2017;92(11):1515-1524. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001714

Ogur B, Hirsh D, Krupat E, Bor D. The Harvard Medical School-Cambridge Integrated Clerkship: An innovative model of clinical education. Acad Med. 2007;82:397-404. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803338f0.

Zink T, Power D, Finstad D, Brooks K. Is there equivalency between students in a longitudinal, rural clerkship and a traditional urban-based program? Fam Med. 2010;42:702-706.

Hirsh D, Gaufberg E, Ogur B, et al. Educational outcomes of the Harvard Medical School-Cambridge Integrated Clerkship: A way forward for medical education. Acad Med. 2012;87:643-650. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31824d9821.

Latessa R, Beaty N, Royal K, Colvin G, Pathman DE, Heck J. Academic outcomes of a community-based longitudinal integrated clerkships program. Med Teach. 2015; 37:862-867. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2015.1009020.

Association of American Medical Colleges. Academic Level Length Distribution in US and Canadian Medical Schools: 2012-2013 and 2016-2017 and 2018-2019. Curriculum Inventory. https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/cir/451832/ci05.html. Accessed February 18, 2021.

Association of American Medical Colleges. Curriculum Change in US Medical Schools 2017-2018. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/curriculum-reports/interactive-data/curriculum-change-us-medical-schools. Curriculum Inventory. Accessed February 18, 2021

Jurich D, Santen SA, Paniagua M, et al. Effects of Moving the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 After Core Clerkships on Step 2 CK Clinical Knowledge Performance. Acad Med. 2020;95(1):111-121. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002921.

Jurich D, Daniel M, Paniagua M, et al. Moving the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 after core clerkships: An outcomes analysis. Acad Med. 2019;94:371-377. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002458.

Rockney RM, Allister RG. Dropping the shelf examination: does it affect student performance on the United States Medical Licensure Examination Step 2?. Ambul Pediatr. 2005;5(4):240-243. https://doi.org/10.1367/A04-138R.1.

Fitzmaurice, G.M., Laird, N.M., & Ware, J.H. (2011). Marginal Models: Generalized estimating equations (GEE). In D.J. Balding et al. (Eds.). Applied longitudinal analysis 2nd edition (pp. 353-394). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

SAS Institute Inc 2013. SAS/ACCESS® 9.4 Interface to ADABAS: Reference. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

NBME Annual Report, 2020. https://www.nbme.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/2017Annual-Report.pdf. Last Accessed May 26, 2021

USMLE, Content Outline and Specifications. https://usmle.org/step-2-ck/#contentoutlines. Last Accessed February 11, 2021.

Haist SA, Butler AP, Paniagua MA. Testing and evaluation: The present and future of the assessment of medical professionals. Adv Physiol Educ. 2017;41:149-153. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00001.2017.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the following who contributed logistical support, emotional energy, and data to this paper: Adam Cifu, Kirk Bronander, Sean Whelton, Martin Muntz, Michael Battistone, Shobhina Chheda, Cynthia Ledford, Doug Walden, Monalisa Taylor, Karen Hauer, Alisa Peet, Amy Shaheen, Deborah Deeway, Janet Jokela, John Dorsey, Andrew Hoellein, Michael Battistone, John Kugler, Renee Dversal, Nicholas Van Wagoner, John Pittman, Gary Stallings, Jeffery Becker, Oliver Cequeria, Briar Duffy, Patrick McMillan, Pat Foy, Saurabh Bansal, Maureen Lowery, Michael Elnicki, and Krisi Kosub. We also wish to thank Linette Ross, senior psychometrician for the NBME, who helped with data referencing and analysis through the NBME. We also wish to thank Gail Hendler for her help with numerous literature searches during the investigation.

The following authors of this manuscript had access to the data, fully contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript, and, ultimately, fully met the criteria for authorship:

Matthew Fitz, MD, MS, was the Clerkship Director of Internal Medicine at Loyola University Stritch School of Medicine and is now the Vice Chair for faculty development in the Department of Medicine at Loyola University Stritch School of Medicine.

William Adams, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Medicine, Medical Education, and Public Health Sciences at Loyola University Stritch School of Medicine.

Marc Heincelman, MD, MPH, is the Clerkship Director at Medical University of South Carolina.

Steve Haist, MD, was the Vice President for Test Development for the National Board of Medical Examiners and is now the Associate Dean for the University of Kentucky College of Medicine-Northern Kentucky Campus.

Karina Whelan, MD, is the Clerkship Co-Director at University of North Carolina School of Medicine.

LeeAnn Cox, MD, is the Clerkship Director at Indiana University School of Medicine.

Uyen-Thi Cao, MD, is the Clerkship Director at Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine.

Susan Hingle, MD, is an Associate Dean for Human and Organizational Potential at Southern Illinois School of Medicine.

Amanda Raff, MD, is the Clerkship Director at Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Bruce Houghton, MD, is the Clerkship Director at Creighton University School of Medicine.

Janet Fitzpatrick, MD, is the Clerkship Director at Drexel University College of Medicine.

Ryan Nall, MD, is the Clerkship Director at the University of Florida College of Medicine.

Jennifer Foster, MD, is the Clerkship Director at Florida Atlantic University Charles E Schmidt College of Medicine.

Jonathan Appelbaum, MD, is the Education Director for Internal Medicine at Florida State University College of Medicine.

Cyril Grum, MD, is the Clerkship Director at the University of Michigan Medical School.

Anna Donovan, MD, MS, was a Clerkship Director at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and is now an Associate Program Director.

Stuart Kiken, MD, is the Clerkship Director at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science.

Reeni Abraham, MD, is the Clerkship Director at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School

Marti Hlafka, MD, is the Clerkship Director at Southern Illinois School of Medicine.

Chad Miller, MD, is the Clerkship Director at Tulane University Medical School.

Saurabh Bansal, MD, is the Clerkship Director at the University of Illinois College of Medicine, Peoria.

Douglas Paauw, MD, is the Clerkship Director at University of Washington School of Medicine.

Cindy J Lai, MD, is the Clerkship Director at the University of California, San Francisco.

Amber Pincavage, MD, is the Clerkship Director at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine.

Gauri Agarwal, MD, is the Clerkship Director at University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

Cynthia Burns, MD, was the Clerkship Director at Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Horatio Holzer, MD, is the Clerkship Director at Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai.

Katie Lappé, MD, is the Clerkship Director at the University of Utah School of Medicine.

Viju John, MD, MS is the Clerkship Director at Rush Medical College.

Blake Barker, MD, is the Clerkship Director at University of Texas Southwestern Medical School.

Nina Mingioni, MD, is the Clerkship Director at Thomas Jefferson University Sidney Kimmel Medical College.

Deepti Rao, MD, is the Clerkship Director at University of New Mexico School of Medicine.

Laura Zakowski, MD, is the Clerkship Director at University of Wisconsin School of Public Health.

Chayan Chakraborti, MD, is the Clerkship Director at Tulane University School of Medicine.

Winter Williams, MD, is the Clerkship Director at the UAB Heersink School of Medicine.

William Kelly, MD, is the Clerkship Director at the Uniformed Services University

Data

The National Board of Medical Examiners provided the de-identified data used in this analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

During the recruitment period, the participating clerkship directors obtained institutional review board (IRB) approval or exemption from their respective institutions. The co-investigators from the National Board of Medical Examiners received IRB exemption from the American Institutes for Research.

Disclaimers

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of the Uniformed Services University or the Department of Defense.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A group of Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine and co-investigators partnered to form the CDIM-NBME EXPRESS study group and have authored this manuscript. Their titles are included from the time of the study.

Previous presentations

Matthew M. Fitz presented the data in this article during grand rounds at Loyola University Stritch School of Medicine (Chicago, Illinois) in the Spring of 2018, at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine (Orlando, Florida) in the Spring of 2018, and at the Medical University of South Carolina (virtual) in the Spring of 2020.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fitz, M., Adams, W., Heincelman, M. et al. The Impact of Internal Medicine Clerkship Characteristics and NBME Subject Exams on USMLE Step 2 Clinical Knowledge Exam Performance. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 2208–2216 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07520-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07520-6