Abstract

Background

Mobile mammographic services (MM) have been shown to increase breast cancer screening in medically underserved women. However, little is known about MM patients’ adherence to follow-up of abnormal mammograms and how this compares with patients from traditional, fixed clinics.

Objectives

To assess delays in follow-up of abnormal mammograms in women screened using MM versus fixed clinics.

Design

Electronic medical record review of abnormal screening mammograms.

Subjects

Women screened on a MM van or at a fixed clinic with an abnormal radiographic result in 2019 (N = 1,337).

Main Measures

Our outcome was delay in follow-up of an abnormal mammogram of 60 days or greater. Guided by Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization, we assessed the following: predisposing (age, ethnicity, marital status, preferred language), enabling (insurance, provider referral, clinic site), and need (personal breast cancer history, family history of breast/ovarian cancer) factors.

Key Results

Only 45% of MM patients had obtained recommended follow-up within 60 days of an abnormal screening compared to 72% of fixed-site patients (p < .001). After adjusting for predisposing, enabling, and need factors, MM patients were 2.1 times more likely to experience follow-up delays than fixed-site patients (CI: 1.5–3.1; p < .001). African American (OR: 1.5; CI: 1.0–2.1; p < .05) and self-referred (OR: 1.8; CI: 1.2–2.8; p < .01) women were significantly more likely to experience delays compared to Non-Hispanic White women or women with a provider referral, respectively. Women who were married (OR: 0.63; CI: 0.5–0.9; p < .01), had breast cancer previously (OR: 0.37; CI: 0.2–0.8; p < .05), or had a family history of breast/ovarian cancer (OR: 0.76; CI: 0.6–0.9; p < .05) were less likely to experience delayed care compared to unmarried women, women with no breast cancer history, or women without a family history of breast/ovarian cancer, respectively.

Conclusions

A substantial proportion of women screened using MM had follow-up delays. Women who are African American, self-referred, or unmarried are particularly at risk of experiencing delays in care for an abnormal mammogram.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death in women in the United States (US).1 Over 281,000 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer and 44,000 will die from this disease in 2021.1 Early detection using screening mammography is critical for maximizing treatment effectiveness and long-term survival.2,3,4 Although mammography screening is associated with a 20–35% decline in breast cancer mortality, mammography screening can only enhance survival if appropriate follow-up is received.5,6,7 Delaying follow-up of abnormal mammograms has been shown to lead to later stage at diagnosis, larger tumor size, and poorer prognosis.8,9

Unfortunately, women from racial/ethnic minority and low-income groups have experienced longer days to resolution of abnormal mammograms.10,11,12 Compared to Non-Hispanic White (NHW) women, African American women were nearly 3 times less likely to receive follow-up within 90 days of an abnormal screening.13,14 A national study revealed that the number of days for Hispanic women to reach diagnosis is double to triple that of NHW women.15 Furthermore, women with incomes < $10,000 were found to complete follow-up 1.5 times slower than women with incomes ≥ $50,000.16 Reasons for these disparities range from system-level (e.g., cost, transportation, health insurance) to provider-level (e.g., poor communication, disrespectful behavior) to personal barriers (e.g., mistrust, fear, lack of understanding).17,18.

To address gaps in care for medically underserved women, mobile mammography (MM) performed on vans has been employed to remove geographical, financial, and other access barriers to screening mammogram utilization.19 MM vans frequently travel to areas with no radiology clinics, large concentrations of racial/ethnic minorities, and high poverty. They typically offer screening mammograms at no/low cost. While MM vans have been widely successful in increasing breast cancer screening adherence, there is some indication that women attending MM vans experience greater delays in obtaining follow-up than women from fixed clinics.19,20,21,22,23,24,25 To better understand this problem, we undertook the current study to assess delays in follow-up between MM patients and those of a fixed clinic, and examine factors contributing to follow-up delays after an abnormal finding.

To guide our study design, we used Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization (Fig. 1), which posits that a person’s utilization of health care services is a function of her predisposing characteristics (e.g., demographics), enabling resources (e.g., health insurance), and need factors (e.g., perceived health status).26,27 We hypothesized that these access factors contributed to the likelihood of women receiving timely care for an abnormal mammogram and that each group of factors increasingly helps explain potential disparities in delayed follow-up detected.

METHODS

Data Source and Procedures

We conducted an analysis of electronic medical records from a MM van and fixed radiology clinic serving the New York City (NYC) area. Records were included from patients who self-identified as women and completed a screening mammogram between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2019, that resulted in a finding of BI-RADS 0 (prompting further evaluation) including technical recalls. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

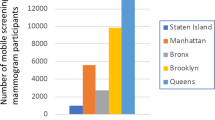

Mount Sinai Mobile Mammography Van

The van travels to all boroughs of NYC and primarily serves patients who are low-income, racial/ethnic minorities, and uninsured. It collaborates with the NY State Cancer Services Program to cover the costs of screening mammograms (and subsequent treatment) for uninsured women.

Fixed Clinic

The fixed clinic is located in East Harlem, where the poverty rate is twice that of NYC (34% vs. 16%) and residents are predominantly Hispanic (43%) and African American (36%).28 The clinic primarily serves patients with public health insurance.

Measures

Outcome Measure

“Delayed follow-up” was determined as having received/not received a diagnostic exam (e.g., ultrasound, MRI, biopsy) or evaluation of prior images > 60 days from receipt of screening mammogram. Women who never received follow-up were considered to be delayed. This definition is in line with guidelines set forth by the Centers for Disease Control’s National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program.29.

Predisposing Characteristics

We measured predisposing factors using patient’s age, ethnicity, marital status, and preferred language. Age was assessed as follows: 40–49 years, 50–74 years, and 75 + years in correspondence with the United States Preventive Services Task Force screening guidelines. We measured ethnicity through patient self-identification as follows: NHW, African American, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, or Other. Marital status was categorized as “unmarried/married.” Women in a domestic partnership were considered “married.” Women who were separated were considered “unmarried.” The preferred language was classified as English/non-English.

Enabling Resources

We included health insurance, clinic site location, and primary care provider (PCP) referral as enabling factors. Health insurance was categorized as “private,” “public,” or “uninsured.” Women were classified as MM patients or fixed-clinic patients depending on where they received their screening (index) mammogram. Women who were referred from their PCP were considered to have a PCP referral; otherwise, they were considered as self-referred.

Need Factors

We assessed need factors through patient records of personal breast cancer history (yes/no) and report of any family history of breast/ovarian cancer (yes/no).

Statistical Analyses

To provide a profile of the study sample, we calculated count and proportion of patient characteristics by clinic site (Table 1). Examination of any significant differences between groups was assessed using chi-square tests (p < 0.05). The relationship between predictor variables and delayed follow-up was examined using logistic regression analysis. Simple logistic regression was conducted to examine potential associations between individual predictor variables and delayed follow-up. Multiple logistic regression analyses were then performed to determine the odds of delayed follow-up after controlling for all predictors in the model. To assess model fit, factors were entered sequentially in blocks according to Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization. Goodness-of-fit was assessed through examination of changes in the likelihood ratio test statistic. A p value < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4.

RESULTS

Descriptive Analysis

Characteristics of the study population by clinic site are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients were between ages 50–74 years; there were no age differences by site. Overall, more MM than fixed-site patients were racial/ethnic minorities (90% vs. 79%), unmarried (86% vs. 72%), preferred a non-English language (27% vs. 13%), and uninsured (27% vs. 3%). No site differences were observed regarding personal breast cancer history. More fixed-site patients reported having a family history of breast/ovarian cancer than MM patients (29% vs. 20%).

Bivariate Analysis

We found that 37% of the study sample were delayed in receiving follow-up (Table 2). In assessing differences in delays by site, chi-square tests revealed that 55% of MM patients had delayed follow-up ≥ 60 days compared to 28% of fixed-site patients (p < 0.001).

Simple logistic regression analysis (not shown) revealed MM patients were 3.1 times more likely to have delayed follow-up than fixed-site patients (p < 0.001). Women who were African American (OR:1.8; p < 0.01), Hispanic (OR:1.4; p < 0.05), Asian/Pacific Islander (OR:1.9; p < 0.01), or other racial/ethnic identity (OR:2.8; p < 0.05) were more likely to experience delays in care compared to NHW women; individuals with no insurance were more likely to have delayed care than those with private insurance (OR:2.0; p < 0.001); and patients without a PCP referral were 3.2 times more likely to experience delays in follow-up than those with a referral (p < 0.001). Being married (versus unmarried [OR: 0.5; p < 0.001]), having a personal breast cancer history (versus no history [OR: 0.3; p < 0.01]), or having family history of breast or ovarian cancer (versus no history [OR: 0.7; p < 0.01]) were associated with lower likelihoods of having delayed follow-up after an abnormal mammogram.

Multivariate Analysis

As shown in the final model (Table 3), multiple logistic regression revealed that MM patients had 2.1 greater odds of having delayed follow-up compared to fixed-clinic patients, after controlling for all other variables in the model (p < 0.001). Women who identified as African American were 1.5 times more likely to experience follow-up delays than NHW women, after controlling for all other factors (p < 0.05). Women who identified their race/ethnicity as “Other” also were more likely to be delayed compared to NHW women (OR: 3.1; p < 0.01). Furthermore, women who were self-referred were 1.8 times more likely to be delayed (p < 0.01) than women with a PCP referral. Being married (versus not married [OR: 0.6; p < 0.01]), having a personal breast cancer history (versus no history [OR: 0.4; p < 0.05]), having or a family history of breast or ovarian cancer (versus no family history [OR: 0.8; p < 0.05]) were associated with a lower likelihood of delays in the final model. No other factors significantly predicted delays in follow-up after accounting for all other variables.

Model Fit

The likelihood ratio test (LRT) showed that the addition to the model of each set of predisposing characteristics (LRT: 36.38; p < 0.001), enabling resources (LRT: 120.07; p < 0.001), and need factors (LRT: 131.32; p < 0.001) improved the model’s accuracy in predicting delayed follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Findings from the current study indicate disparities exist in timely follow-up of abnormal mammograms among women utilizing MM. Only 45% of MM patients in our study received recommended follow-up care within 60 days compared to 72% of patients who attended a fixed clinic. After controlling for predisposing characteristics, enabling resources, and need factors, we found that MM women were 2.1 times significantly more likely to delay follow-up care than those from the fixed clinic. Although our results are discouraging, they are not out of line with previous findings. Other researchers have found 40–57% of MM women fail to receive follow-up care within 60 days of an abnormal screening; 17% never complete follow-up.21,24,25 Given that MM was designed to address transportation, financial, and other logistical barriers to breast cancer screening, we suspect that access factors are important systemic determinants of receiving timely follow-up care in this patient population. MM patients in our study who received an abnormal finding would have had to travel to a fixed clinic to obtain diagnostic care. Therefore, providing diagnostic care on a mobile clinic unit may improve access to follow-up, while promoting routine screening.

Our observed low follow-up in MM patients could also be due to patients’ difficulty understanding mammogram reports or the importance of timely follow-up. Several researchers have found that despite having received mammogram letters and/or reports, many women do not fully comprehend their results.30,31,32 One study reported that 55% of MM patients who had poor follow-up were not even aware that their mammogram was abnormal.24 Given that women who use MM are frequently from groups with low education and limited health literacy,19,33,34,35 difficulty understanding lay letters and mammogram reports can be a serious barrier to timely follow-up. While adding phone communication has improved follow-up adherence,36,37 our own experience suggests it may be necessary to explore alternative strategies for clearly communicating the importance of follow-up. As standard protocol, all patients in our study received phone calls regarding their abnormal results and the need for follow-up care (in addition to letters in the patient’s preferred language). Women who could not be reached by phone received at minimum 3 phone calls and 3 letters (with the last letter being certified). Despite these measures, our study still found that MM patients were more likely to have follow-up delays. A low perceived need for follow-up care could help explain this problem, as one study reported 20% of MM patients who delayed follow-up did not perceive it to be a high priority, particularly in the absence of symptoms.24 In addition, women who attend MM may have multiple competing demands for their time (e.g., caregiving, multimorbidity, difficulty meeting basic needs) that are prioritized over their own health.15,24 Thus, efforts to promote timely follow-up may benefit not only from improving the readability of mammogram letters, but also from addressing structural barriers to follow-up care, developing public health policies that prioritize early breast cancer detection, and increasing breast health education.19 Future research should explore systemic reasons for why some women do not adhere to follow-up recommendations, despite receiving communication regarding abnormal results.

Our study also found that African American women were 1.5 times more likely to have delays in follow-up compared to NHW women. This finding echoes those of the extant literature, which report African American women experience significantly longer days to diagnosis, are 1.5–3.5 times more likely to experience delays ≥ 60 days, and are 12% more likely to never receive follow-up care than NHW women, even after adjusting for income, insurance type, and other health access factors.38,39,40,41,42,43 The inequity between timely follow-up in African American women screened on MM when compared to NHW women screened on MM can fundamentally be explained by structural racism.44,45,46 Medical mistrust, discrimination, stigma, fear of a cancer diagnosis, and a lack of knowledge of breast cancer and screening resources have been identified as factors contributing to inequities in follow-up and treatment in African American women.47,48,49,50,51 Community-based, breast health education programs have been shown to alleviate many of these concerns and to improve African American women’s breast cancer knowledge and screening.52,53 Patient navigation programs have also been found to improve access to breast cancer screening and increase screening mammography completion in underserved women.54,55 Thus, community-based, breast health education and patient navigation programs may be key for promoting timely follow-up of abnormal mammograms in African American women.

Women who identified as being from an “other racial/ethnic minority” group were also found to have greater odds of delaying follow-up than NHW women. Although the sample size for the “other racial/ethnic minority” group was quite small, our finding could indicate that women from less-recognized minority groups face increased and/or unique, unaddressed barriers to follow-up care. More research with a larger sample size is needed to better identify the ethnic background of these women and to understand the unique barriers that women from less-recognized racial/ethnic groups face in obtaining follow-up care.

Our study also suggests being married is protective against experiencing a delayed follow-up for an abnormal mammogram. This finding is in line with the literature, which associates being married with higher adherence to breast cancer screening and treatment guidelines.56,57,58,59 It is possible that a marital partner serves as a critical source of social support to women undergoing a potential cancer diagnosis. Having a marital partner might also provide greater resources for obtaining needed health care, such as increased household income or childcare coverage to attend exams. Thus, it is important to recognize non-married women as a potentially high-risk group for delayed follow-up. Future research should explore the potential pathways leading to poor follow-up in non-married women in order to improve diagnostic rates in this group.

Furthermore, we found that self-referred women were 1.8 times more likely to experience delays than women who had a PCP referral. This is not surprising, given the vast literature documenting the important role PCPs play in motivating women to adhere to follow-up recommendations.13,48,60,61,62 Self-referred women may lack appropriate resources for maintaining breast health and continuity of care; thus, they may experience more barriers to receiving timely follow-up. Although self-referral programs have improved access to screening mammography, increased efforts may be needed to ensure self-referred women are obtaining recommended diagnostic care in a timely fashion.63,64 Future research should explore reasons for delays in follow-up and identify effective strategies for promoting timely diagnostic care in self-referred patients.

In addition, our findings confirm those of earlier studies and report that women with a personal breast cancer history or family history of breast or ovarian cancer were less likely to delay follow-up than women with no history.65,66,67,68 A personal breast cancer history or family history of breast or ovarian cancer is a well-established risk factor for developing breast cancer.69,70 It is possible that women with a personal or family history are aware of their heightened susceptibility to the disease and are more vigilant about obtaining early detection for breast cancer. Likewise, it is possible that women without a personal or family history of breast cancer underestimate their risk of developing breast cancer. Therefore, greater effort should be made to educate women about their risk of developing breast cancer in the absence of a genetic predisposition for the disease.

Our study is not without limitations. We drew our data from a single MM van and one fixed-clinic site. Thus, our findings have limited generalizability to women outside of these two clinics. Studies that include greater and more diverse MM and fixed clinics may strengthen our findings and support broader generalization. We also used electronic medical records to conduct our study, which restricted the variables that we were able to examine. For instance, we were unable to capture income, education level, health literacy, or other patient characteristics, which could be important predictors of women’s access to diagnostic testing. In addition, because we only included records from women who had received a screening mammogram, we were unable to examine delays in abnormal mammograms from men (who typically do not receive screening mammograms) and other persons who do not identify as women. Furthermore, while our records included documentation of follow-up done outside of our institution (as federally mandated), not all diagnostic care completed outside of our health care system could be confirmed. Moreover, our analysis consisted of some small cell sizes (e.g., “other race/ethnicity,” uninsured, personal breast cancer history) that limited reliability and interpretability of our findings. Research with a larger sample size is recommended to improve our understanding of how these factors may influence follow-up care.

Implications for Mobile Mammography Clinics

Despite these limitations, our study sheds important light on the relationship between MM use and delayed follow-up. Extending MM services to include diagnostic care (preferably same-day) on MM vans may help address access barriers; thus future efforts should explore economically feasible ways in which diagnostic MM can be performed.71 Studies have also shown that providing emotional support and breast health education to women with abnormal findings can promote follow-up adherence.72,73 Thus, providing patient navigation and health education on MM vans may be key for improving timely follow-up. Future research should examine system-level factors that drive delays and inequities in follow-up among MM patients and develop strategies for addressing and overcoming these barriers.

REFERENCES

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2021;71(1):7–33.

Brown ML, Houn F, Sickles EA, Kessler LG. Screening mammography in community practice: positive predictive value of abnormal findings and yield of follow-up diagnostic procedures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:1373-1377.

Elmore JG, Armstrong K, Lehman CD, Fletcher SW. Screening for breast cancer. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1245–1256. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.10.1245

Zuckerman HC. The role of mammography in the diagnosis of breast cancer. In: Ariel IM, Clearly JB, eds. Breast Cancer—Diagnosis and Treatment. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1987:152–172.

Kerlikowske K, Grady D, Rubin SM, Sandrock C, Ernster VL. Efficacy of screening mammography: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1995;273(2):149–154.

Fletcher SW, Elmore JG. Mammographic screening for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1672-1680.

Berry DA, Cronin KA, Plevritis SK, et al. Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1784-1792.

Olivotto IA, Gomi A, Bancej C, et al. Influence of delay to diagnosis on prognostic indicators of screen-detected breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:2143‐2150.

Richards MA, Westcombe AM, Love SB, Littlejohns P, Ramirez AJ. Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet. 1999;353:1119‐1126.

Press R, Carrasquillo O, Sciacca RR, Giardina EV. Racial/ethnic disparities in time to follow-up after an abnormal mammogram. J Womens Health. 2008;17:6.

Nguyen KH, Pasick RJ, Stewart SL, Kerlikowske K, Karliner LS. Disparities in abnormal mammogram follow-up time for Asian women compared with non-Hispanic white women and between Asian ethnic groups. Cancer. 2017;123: 3468-3475. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30756

Selove R, Kilbourne B, Fadden MK, et al. Time from screening mammography to biopsy and from biopsy to breast cancer treatment among black and white, women Medicare beneficiaries not participating in a health maintenance organization. Womens Health Issues. 2016;26(6):642-647.

Jones BA, Dailey A, Calvocoressi L, et al. Inadequate follow-up of abnormal screening mammograms: Findings from the race differences in screening mammography process study. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:809–821.

McCarthy AM, Kim JJ, Beaber EF, et al. Follow-up of abnormal breast and colorectal cancer screening by race/ethnicity. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(4):507-512.

Ramirez AG, Pérez-Stable EJ, Talavera GA, et al. Time to definitive diagnosis of breast cancer in Latina and non-Hispanic white women: the six cities study. SpringerPlus. 2013;2:84.

Krok-Schoen JL, Kurta ML, Weier RC, et al. Clinic type and patient characteristics affecting time to resolution after an abnormal cancer-screening exam. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(1):162-168.

Wujcik D, Fair AM. Barriers to diagnostic resolution after abnormal mammography. Cancer Nursing. 2008;31(5):E16-E30.

Reece JC, Neal EFG, Nguyen P, McIntosh JG, Emery JD. Delayed or failure to follow-up abnormal breast cancer screening mammograms in primary care: a systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:373.

Vang S, Margolies LR, Jandorf L. Mobile mammography participation among medically underserved women: A systematic review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:E140.

Guillaume E, Launay L, Dejardin O, et al. Could mobile mammography reduce social and geographic inequalities in breast cancer screening participation? Prev Med. 2017;100:84-88.

Stanley E, Lewis MC, Irshad A, et al. Effectiveness of a mobile mammography program. Am J Roentgenol. 2017;209(6):1426-1429.

Brooks SE, Hembree TM, Shelton BJ, et al. Mobile mammography in underserved populations: analysis of outcomes of 3,923 women. J Community Health. 2013;38:900–906.

Fontenoy AM, Langlois A, Chang SL, et al. Contribution and performance of mobile units in an organized mammography screening program. Can J Public Health. 2013;104:e193-e199.

Peek ME, Han JH. Compliance and self-reported barriers to follow-up of abnormal screening mammograms among women utilizing a county mobile mammography van. Health Care for Women Int. 2009;30(10):857-870.

Pisano ED, Yankaskas BC, Ghate SV, Plankey MW, Morgan JT. Patient compliance in mobile screening mammography. Acad Radiol. 1995;2(12):1067-1072.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1-10.

Andersen RM. A Behavioral Model of Families’ Use of Health Services. Chicago, IL: Center for Health Administration Studies; 1968.

NYU Furman Center. Neighborhood profiles: East Harlem Manhattan 11. https://furmancenter.org/neighborhoods/view/east-harlem. Accessed Aug. 25, 2021.

DeGroff A, Royalty JE, Howe W, et al. When performance management works: A study of the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program. Cancer. 2014;120: 2566-2574.

Karliner LS, Kaplan CP, Juarbe T, Pasick R, Perez-Stable EJ. Poor patient comprehension of abnormal mammography results. J Gen Int Med. 2005;20:432-437.

Marcus EN, Sanders LM, Pereyra M, et al. Mammography result notification letters: Are they easy to read and understand? J Womens Health. 2011;20(4):541-555.

Nguyen DL, Harvey SC, Oluyemi ET, Myers KS, Mullen LA, Ambinder EB. Impact of improved screening mammography recall lay letter readability on patient follow-up. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(11):1429-1436.

Faguy K. Challenges of the underserved and underscreened in mammography. Radiologic Technology. 2020;91(3):267M-281M.

Vyas A, Madhavan S, Kelly K, Metzger A, Schreiman J, Remick S. Do Appalachian women attending a mobile mammography program differ from those visiting a stationary mammography facility? J Comm Health. 2013;38:698-706.

Chiweshe J. An analysis of the role of Medicaid expansion on mobile mammography units and breast cancer screening in the Commonwealth of Kentucky. [Dissertation]. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky; 2016.

Nguyen DL, Oluyemi E, Myers KS, Harvey SC, Mullen LA, Ambinder EB. Impact of telephone communication on patient adherence with follow-up recommendations after an abnormal screening mammogram. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(9):1139-1148.

Schapira MM, Barlow WE, Conant EF, et al. Communication practices of mammography facilities and timely follow-up of a screening mammogram with a BI-RADS 0 assessment. Acad Radiol. 2018;25(9):1118-1127.

Maly RC, Leake B, Mojica CM, Liu Y, Diamant AL, Thind A. What influences diagnostic delay in low-income women with breast cancer? J Womens Health. 2011;20(7):1017-1023.

Adams SA, Smith ER, Hardin J, Prabhu-Das I, Fulton J, Hebert JR. Racial differences in follow-up of abnormal mammography findings among economically disadvantaged women. Cancer. 2009;115(24):5788-5797.

Warner ET, Tamimi RM, Hughes ME, et al. Time to diagnosis and breast cancer stage by race/ethnicity. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136:813–821. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-012-2304-1

Hoffman HJ, LaVerda NL, Levine PH, et al. Having health insurance does not eliminate race/ethnicity‐associated delays in breast cancer diagnosis in the District of Columbia. Cancer. 2011;117:3824-3832.

Perez-Stable EJ, Afable-Munsuz A, Kaplan CP, et al. Factors influencing time to diagnosis after abnormal mammography in diverse women. J Womens Health. 2013;22(3).

George P, Chandwani S, Gabel M, et al. Diagnosis and surgical delays in African American and White women with early-stage breast cancer. J Womens Health. 2015;24(3):209-217.

Pallok K, De Maio F, Ansell DA. Structural racism—a 60-year-old black woman with breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;380(16):1489-1493.

Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. The Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463.

Beyer KMM, Young S, Bemanian A. Persistent racial disparities in breast cancer mortality between black and white women: What is the role for structural racism? In: Berrigan D, Berger NA, eds. Geospatial Approaches to Energy Balance and Breast Cancer. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2019:361-378.

Kim SK, Glassgow AE, Watson KS, Molina Y, Calhoun EA. Gendered and racialized social expectations, barriers, and delayed breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer. 2018;124(22): 4350-4357.

Nonzee NJ, Ragas DM, Luu TH, et al. Delays in cancer care among low-income minorities despite access. J Womens Health. 2015;24(6):506-514.

Passmore SR, Williams-Parry KF, Casper E. Message received: African American women and breast cancer screening. Health Promotion Practice. 2017; 18(5):726-733.

Ferrera MJ, Feinstein FT, Walker WJ, Gehlert SJ. Embedded mistrust then and now: findings of a focus group study on African American perspectives on breast cancer and its treatment. Crit Public Health. 2016;26(4):455-465.

Jones CE, Maben J, Jack RH, et al. A systematic review of barriers to early presentation and diagnosis with breast cancer among black women. BMJ Open. 2013; 014;4:e004076.

Hempstead B, Green C, Briant KJ, Thompson B, Molina Y. Community empowerment partners: Health education program for African-American women. J Comm Health. 2018;43:833-841.

Sadler GR, Ko CM, Cohn JA, White M, Weldon R, Wu P. Breast cancer knowledge, attitudes, and screening behaviors among African American women: the Black cosmetologists promoting health program. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:57.

Hunt BR, Allgood KL, Kanoon JM, Benjamins MR. Keys to the successful implementation of community-based outreach and navigation: Lessons from a breast health navigation program. J Canc Educ. 2017;32:175-182.

Mason TA, Thompson WW, Allen D, Rogers D, Gabram-Mendola S, Jacob Arriola KR. Evaluation of the Avon Foundation community education and outreach initiative community patient navigation program. Health Promotion Practice. 2013;14(1):105-112.

Patel K, Kanu M, Liu J, et al. Factors influencing breast cancer screening in low-income African Americans in Tennessee. J Comm Health. 2014;39(5):943–50.

Camacho FT, Tan X, Alcala HE, Shah S, Anderson RT, Balkrishnan R. Impact of patient race and geographical factors on initiation and adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in Medicare breast cancer survivors. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(24):e7147.

Hanske J, Meyer CP, Sammon JD, et al. The influence of marital status on the use of breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening. Prev Med. 2016;89:140-145.

Martinez ME, Unkart JT, Tao L, et al. Prognostic significance of marital status in breast cancer survival: A population-based study. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0175515.

Bastani R, Yabroff KR, Myers RE, Glenn B. Interventions to improve follow-up of abnormal findings in cancer screening. Cancer. 2004;101(S5):1188-1200.

Zapka J, Taplin SH, Price RA, Cranos C, Yabroff R. Factors in quality care—the case of follow-up to abnormal cancer screening tests—problems in the steps and interfaces of care. JNCI Monographs. 2010;40:58–71.

Roetzheim RG, Ferrante JM, Lee J, et al. Influence of primary care on breast cancer outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(5):401-411.

Moiel D, Thompson J. Early detection of breast cancer using a self-referral mammography process: The Kaiser Permanente Northwest 20-year history. Perm J. 2014;18(1): 43–48.

Peek ME, Han J. Mobile mammography: assessment of self-referral in reaching medically underserved women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(4):398-403.

Ambinder EB, Myers K, Panigrahi B, et al. Breast MRI BI-RADS 3: Impact of patient-level factors on compliance with short-term follow-up. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(3):377-383.

Petrisek A, Campbell S, Laliberte L. Family history of breast cancer: Impact on the disease experience. Cancer Practice. 2000; 8(3):135-142.

George M. Experiences of older African American women with breast cancer screening and abnormal mammogram results. [Dissertation]. Minneapolis, MN: Walden University; 2011.

Wernli KJ, Aiello Bowles EJ, Haneuse S, Elmore JG, Buist DSM. Timing of follow-up after abnormal screening and diagnostic mammograms. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(2):162-167.

Colditz GA, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, et al. Family history, age, and risk of breast cancer: Prospective data from the Nurses’ Health Study. JAMA. 1993;270(3):338–343. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1993.03510030062035

Pharoah PD, Day NE, Duffy S, Easton DF, Ponder BA. Family history and the risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 1997;71(5):800-9.

Committee on Improving Mammography Quality Standards. Improving interpretive performance in mammography. In Nass S, Ball J, eds. Improving Breast Imaging Quality Standards. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2005:24-81.

Oboite JC. The impact of patient navigation and education on improving compliance follow-up after an abnormal mammogram. [Dissertation]. Irvine, CA: Brandman University; 2021.

Tsapatsaris A, Reichman M. Project ScanVan: Mobile mammography services to decrease socioeconomic barriers and racial disparities among medically underserved women in NYC. Clinical Imaging. 2021;78:60-63.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32CA225617. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations

Preliminary results from an earlier version of this manuscript were presented at the Society of Behavioral Medicine Annual Meeting, April 12–16, 2021.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vang, S.S., Dunn, A., Margolies, L.R. et al. Delays in Follow-up Care for Abnormal Mammograms in Mobile Mammography Versus Fixed-Clinic Patients. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 1619–1625 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07189-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07189-3