Abstract

Background

Polypharmacy is associated with the increased use of potentially inappropriate medications, where the risks of medicine use outweigh its benefits. Stopping medicines (deprescribing) that are no longer needed can be beneficial to reduce the risk of adverse events. We summarized the willingness of patients and their caregivers towards deprescribing.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted in four databases from inception until April 30, 2021 as well as search of citation of included articles. Studies that reported patients’ and/or their caregivers’ attitude towards deprescribing quantitatively were included. All studies were independently screened, reviewed, and data extracted in duplicates. Patients and caregivers willingness to deprescribe their regular medication was pooled using random effects meta-analysis of proportions.

Results

Twenty-nine unique studies involving 11,049 participants were included. All studies focused on the attitude of the patients towards deprescribing, and 7 studies included caregivers’ perspective. Overall, 87.6% (95% CI: 83.3 to 91.4%) patients were willing to deprescribe their medication, based upon the doctors’ suggestions. This was lower among caregivers, with only 74.8% (49.8% to 93.8%) willing to deprescribe their care recipients’ medications. Patients’ or caregivers’ willingness to deprescribe were not influenced by study location, study population, or the number of medications they took.

Discussion

Most patients and their caregivers were willing to deprescribe their medications, whenever possible and thus should be offered a trial of deprescribing. Nevertheless, as these tools have a poor predictive ability, patients and their caregivers should be engaged during the deprescribing process to ensure that the values and opinions are heard, which would ultimately improve patient safety. In terms of limitation, as not all studies may published the methods and results of measurement they used, this may impact the methodological quality and thus our findings.

Open Science Framework registration

https://osf.io/fhg94

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Polypharmacy, or the use multiple medications (usually defined as five or more medicines), is common among older adults (aged 55 years and older) with multi-morbidities to manage their medical conditions. Between 20 and 65% of older adults takes 5 or more medicines daily, increasing the risk of falls, adverse drug events, hospitalization, and even death among this population.1,2,3 As such, stopping medications (deprescribing) that are no longer needed can be beneficial.4 Deprescribing, or the process of reducing unnecessary medications, aims to minimize the potential adverse effects to improve health outcomes in individuals.5, 6 Current evidence suggests that deprescribing can improve health outcomes such as falls and mortality rates.4 Health professionals face various challenges during the deprescribing process. These include knowledge and/or skill deficit of practitioners to balance benefit and risk, resource availability, and work practices.7 In addition, barriers such as the lack of interest and financial remuneration for deprescribing activities, as well as inconsistent and outdated policies, do not support deprescribing activities. Despite these challenges, deprescribing can be useful and safe if the medical ethics, risks, and benefits are well considered and balanced. The approach of deprescribing can consist of (1) medication review; (2) identification of the medications that can be withheld, replaced, or reduced; and (3) implementation of a discontinuation program and monitoring patient for improvement in outcomes or adverse events.6

The process of deprescribing should also involve patients, and they should be encouraged to take an active participation in health care decision pertaining to themselves.8 Studies have suggested that patient’s participation can result in enhanced quality of life, better drug adherence and cost-effectiveness, and ultimately improved health outcomes.9 To implement patient-centered care into deprescribing process, it is necessary to prioritize and personalize deprescribing regimen, taking into account the patients’ beliefs, opinions, and needs.10 As healthcare services are now taking a more patient-centered approach, understanding the opinions of patients and their caregivers towards polypharmacy will improve the healthcare service provided to older patients.11 Most studies conducted to date have explored the barriers and opportunities to achieve appropriate polypharmacy, including examining how participants’ extrinsic factors (e.g., demographics, cultural factor) can predict better deprescribing willingness.12,13,14 In addition, evidence from behavioral science suggest that intrinsic factors such as participant’s belief, attitude, and knowledge are also important in ensuring successful deprescribing.15 Therefore, identification of the attitudinal predictors on the desire to deprescribe is important to facilitate deprescribing.

Several tools have been developed to aid with ascertaining patients’ attitudes and willingness to stop their medication. The Patients’ Attitudes Towards Deprescribing (PATD) was a 15-item questionnaire developed in 2013 to explore patients’ attitudes towards deprescribing.16 While useful, the tool had a limited scope since it does not capture all the potential barriers and enablers to deprescribing. In addition, the tool can only be used among older adults without cognitive impairment and not their caregivers or family members who are often involved in their healthcare decisions. As such, the revised Patients’ Attitudes Towards Deprescribing (rPATD) questionnaire was developed in 2016. This improved tool contains 22 items and a scoring utility which can create four factor scores: belief in appropriateness of withdrawal, perceived burden of their medication, concerns about stopping and level of involvement in medication management. Each factor is assigned a score of between 1 and 5, with higher scores indicating higher belief in appropriateness of withdrawal, burden, concerns of stopping, and involvement in medication management

Another tool that developed was the Patient Perceptions of Deprescribing (PPoD) instrument, which contains 30 questions from 8 scales by Linsky and colleagues.17 The authors further refined the instrument in 2020 into an 11-item questionnaire, the Patient Perceptions of Deprescribing–Short Form which can be completed in 5 min.18

Previous reviews have examined the perceptions of older adults towards deprescribing, barriers, and enablers which have affected their decisions, with the aim of achieving deprescribing in practice.14, 19, 20 However, there is an urgent need to translate this knowledge into strategies that can lead to practical deprescribing efforts. One such way is to understand the attitudes towards deprescribing among the general population and their willingness towards deprescribing. This review aims to summarize the perception of patients and their caregivers towards the concept of deprescribing and their willingness to reduce their medications.

METHODS

Search Strategy

Studies were identified through searches on four electronic databases CINAHL, PsychINFO, PubMed, and EMBASE from database inception to April 30, 2021. Keywords and controlled vocabulary related to older adults, and deprescribing including older adults, geriatric, and stopping medicine, were developed in consultation with the medical librarian (eMethods). No limitations were applied on the language of publications. This was supplemented by a search of references from identified studies. The study was registered in Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/fhg94)

Study Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if adults (aged 18 years and above) and/or their caregivers reported their attitudes towards deprescribing using either the PATD, rPATD, or PPoD tool. These tools were chosen since they were the only validated tool to quantitatively capture patient’s view and belief towards deprescribing. Studies could be conducted in any setting including primary care, secondary care, community, or long-term facilities. Qualitative studies, conference abstracts, and letters were excluded.

Studies were selected in two stages. Firstly, all references were imported to Covidence (Melbourne, Australia) and duplicates removed. Next, two reviewers (Y. L. C. and Y. L. W.) independently screened the titles and abstracts for eligibility. Full text of articles were retrieved and screened independently against the eligibility criteria by three reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved through consensus or discussion with the third reviewer (S. W. H. L.).

Data Extraction and Critical Appraisal

Data on the characteristics of the included studies were independently extracted by pairs of reviewers (Y. L. C., Y. L. W., K. W. T., S. L. G.) using a pre-piloted data extraction form. Extracted data include study characteristics, population characteristics, and main findings from each study. Data were then checked for any errors by a third reviewer (S. W. H. L. or K. Y. N.).

The NIH quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies was used to grade the quality of each study.21 The checklist, which consists of 14 items, allows the assessment of strengths and limitations of the study design, conduct, and analysis, and thus the internal validity and risk of bias of the study. Two authors (K. W. T. and S. W. H. L.) independently rated the overall quality rating of each study as good, fair, or poor. In the case of any disagreements, consensus was reached between the reviewers through discussion or consulting a third reviewer (K. Y. N.).

Statistical Analysis

We summarized the results narratively. For the results from rPATD questionnaire, we calculated the average score for each of the four factors, namely the burden factor, appropriateness factor, concern factor, and involvement factor.10 In the event values which were reported as median with corresponding confidence intervals, we converted the values into mean based upon the formula by Hozo et al.22 A meta-analysis of proportion was performed using the “metaprop” command, using the DerSimonian-Laird random effects method after stabilizing the variance of proportion for each study with the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation.23,24,25 This was similarly performed for the global question asking about patients’ willingness to deprescribe from the PATD and rPATD questionnaire.

We conducted a subgroup analysis of the global preference of deprescribing and their satisfaction according to study location (Asia, America, Australia, Europe, or Africa), study setting, and number of medications used. Publication bias was assessed using visual assessment of funnel plots and Egger’s test. Heterogeneity was assessed with the I2 statistics. Data were presented as percentages with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. All analyses were performed on Stata 16.0 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

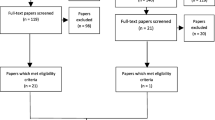

The search identified 1,567 potentially relevant articles, and 1,202 were screened after removal of duplicates. Forty-one articles were screened by title and abstract and 34 articles that were related to 29 unique studies were included in this review11, 17, 18, 26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55 (4 studies17, 31, 48, 51 reported outcomes from the same patient cohort; Fig. 1 and Appendix Table 1). Included studies had recruited a total of 11,049 participants comprising of 10,043 patients and 1,006 caregivers. The median age of participants was 74 years old (range 55 to 87 years), while caregivers was 68 years old (range 50 to 74 years). Twenty seven studies included both female and male participants. The study by Edelman and colleagues26 included only males and the study by Martinez et al41 included only females. These studies were conducted in Asia (n=8), Europe (n=7), Australia (n=6), America (n=4), Canada (n=2), and Africa (n=1). One study was a multinational study conducted in four countries.50 The studies were conducted in various setting including primary care clinics, community pharmacies, hospitals, aged care facilities, and outpatient clinics as well as the general population. The definition of polypharmacy varied in these studies, with one study defining it as taking three or more medication, nine defining it as taking five or more medications, and three defining it as taking six or more medications (Table 1). Based upon the NIH quality assessment tool, most studies were rated to have a low to moderate internal validity (Appendix Table 2). The main source of bias was due to the lack of sample size justification as well as lack of information on the participation rate.

Deprescribing Preference Questionnaires

Studies included in the review examined patients’ attitude towards deprescribing using the PATD (n=13), rPATD (n=14), rPATD for people with cognitive impairment (n=1), and the PPoD or short-form PPoD (n=1) tool. Another seven studies also reported the caregiver’s perspective.30, 31, 33, 44, 49, 50, 53

Willingness to Deprescribe and Medication Satisfaction

Twenty-five studies reported on the patients’ willingness to deprescribe or stop one or more of their regular medications. Pooled analysis of the PATD or rPATD global question asking their willingness to deprescribe found that most older adults were willing to have one or more of their regular medications deprescribed, if the doctor says it was possible (87.6%; 95% CI: 83.3 to 91.4%: Fig. 2). Another eleven studies reported on patient satisfaction with their current medication based upon the rPATD global question, and nearly nine in every ten participants reported satisfaction with their current medication (89.0%; 85.3 to 92.2%; Appendix Figure 1).

Five studies30, 31, 33, 49, 53 included caregivers’ opinion on deprescribing. Pooled analysis noted that 74.8% (49.8 to 93.8%; Appendix Figure 2) of caregivers were willing to reduce their care recipient’s medicines based upon their doctor’s suggestion. These studies also reported that nearly three in every four caregivers were satisfied with their care recipient’s current medicines (79.2%; 56.2 to 95.6%; Appendix Figure 3).

rPATD Factor Scores

Ten studies that reported the respondent scores for the four domains on the rPATD were included in the meta-analysis.26, 30, 31, 33, 37, 43, 49,50,51, 55, 56 Four studies also presented the caregiver participants’ score for each of the domain. The pooled score for each of these factors by participant are summarized in Table 2. In general, the factor scores were generally higher among the caregivers compared to patients, suggesting that most caregivers felt a greater perceived burden, concerns about stopping, and involvement in medication management as well as belief in appropriateness of medication. No summary scores were generated for the PATD or PPoD questionnaires as no scoring system was developed for these tools.

Subgroup Analysis

We attempted to examine if participant and study characteristics impacted patients’ willingness to deprescribe. We did not find any differences in deprescribing preference which were noted if patients were recruited from secondary/tertiary care (including hospital wards, teaching hospital and outpatient clinics), aged care facilities, or primary care (primary care clinics and community pharmacies). No differences were noted among those who took five or more medications compared to those who took six or more medications, by study region or if these studies only recruited older adults aged 60 years and above (Table 3). A similar trend was observed among patient’s satisfaction with their current medication. Visual inspection and Egger’s test did not indicate any evidence of publication bias.

DISCUSSION

To our best knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis that attempted to summarize quantitative studies reporting on attitudes of patients towards deprescribing. Findings from this review suggest that 88% of patients were willing to have their medications deprescribed, whenever possible and advised by their doctor. This is irrespective of participants’ characteristics, study setting, or even socioeconomic status of the country of study. We did note that the willingness to deprescribe was higher in higher income countries such as Japan,38 UK,49 Netherlands,26 and Italy,27 where approximately nine in ten patients were willing to have their medications deprescribed. We postulate that this could be due to the higher health literacy among these patients, who often have good understanding about medications and medical conditions.59, 60 We also noted that this proportion was higher among those who were hospitalized compared to the general population, albeit not reaching statistical significance.

We found the highest scores on the rPATD tool were related to the involvement and satisfaction domain, and lowest scores were related to concern domain. The high involvement score suggests that patients’ wished to be involved in the decision-making process and medication management. In addition, patients also believed in the need and effectiveness of their medication but wanted a trial of stopping their medications. This highlights the importance of taking a patient-centered approach during the deprescribing process as patients felt that they would like to be involved in the decision about their care. As such, prescribers should continuously engage and discuss with their patients on their medication whenever deprescribing is initiated. Some aspects include communicating the risks and benefits of medicine use on the patients, as well as their preferences.

This study noted a variation in the willingness of patients’ and caregivers in their medicine decision-making. Pooled proportion of caregivers’ willingness to deprescribe found that only 75% of the caregivers expressed their willingness to deprescribe compared to 88% among patients’ themselves. This is in agreement with existing studies that reported caregivers often express preference for a more passive role in medicine decision making.

Several systematic reviews to date have reported on the impact of deprescribing on older adults.4, 61 While deprescribing is a complex process requiring a multifaceted approach, these studies have concluded that deprescribing is feasible, with some clinical benefits including a reduction in risk of falls and mortality.4, 61, 62 However, these studies have also highlighted the complex interplay between patients, healthcare providers, and health systems which is often overlooked. Indeed, appropriate prescribing in older adults is challenging due to factors such as age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes, which increases the risk of medication related harms. Additionally, most of the current evidence are often based on single disease and does not take into account the complexities of individuals especially older adults who often suffer from multimorbidity and/or frailty. Thus, to ensure successful deprescribing, it should be approached as part of the prescribing process, where engagement and successful solutions can be developed together with the patients and their caregivers during this period, focusing on the patient’s need as well as safety.

Implications for Practice

This study identified several key findings that will have implications on the safe and appropriate medication deprescribing. One overarching theme identified was that most patients and their caregivers were willing to deprescribe their medications upon the suggestion of their doctor, and they welcomed opportunity to reduce their number of medications taken. These individuals would often be more proactive in involving themselves in the clinical decision-making process. As such, doctors play an important role in identifying this group of patients and actively engage them in the deprescribing process.63 This could involve the development of deprescribing clinics, where a multidisciplinary team of geriatricians, primary care providers, and pharmacists work collaboratively to implement medication deprescribing.

The ability to accurately profile and identify patients amenable to deprescribing can improve clinical efficacy. This has been the aims of the tools identified in the review, but its application in clinical setting was limited due to their poor predictive ability. We noted a high level of agreement for the questions which examined patients’ willingness to deprescribing and their overall satisfaction with the current medication. While patients who are unsatisfied with their medication are thought to be more amenable to deprescribing, this was not the case as patients were willing to have their medications deprescribed despite being satisfied with the current medication.

We offer several potential explanations for this discrepancy. Firstly, all the tools identified in the current study did not perform a predictive validity test to determine if their tool could successfully predict patients’ willingness to deprescribe. This limitation has been noted in a recent study by Turner and colleagues where the authors found that despite 86% of participants indicated willingness to deprescribe on the PATD tool, only 41% had their medications successfully deprescribed.46 This lack of predictive ability may be due to poor perceived benefits of deprescribing by the patients.64 Given these limitations, the global questions in the PATD and rPATD tool should not be viewed in isolation, but interpreted together with the other domains of the rPATD to provide a more complete picture of the patients’ perception.10 The tool should be used together with written information on the perceived risks and benefits of medications, as this have been shown to lead to a more constructive conversation about deprescribing. Studies have shown that when patients do not have a good understanding of the reasons why they were prescribed each of their medications, they were reluctant to reduce their medications.65 Given the expanding scope of practice of clinical pharmacists, they can play a key role in providing education and counseling to patients to improve their medication literacy.66, 67

Another consideration during deprescribing is the target medication and population. As the risk to benefit profile and rationale for prescribing or deprescribing can vary between medicine, it is important that these decisions are individualized taking into context the specific patient needs. For example, the use of statins for preventive treatment may not be appropriate among those with limited life expectancy or those in aged care facilities, and stopping statin therapy is potentially safe and associated with improved quality of life and cost.68 In contrast, stopping levodopa in people with Parkinson’s disease may be inappropriate, as it may lead to worsening of motor symptoms.

While the evidence of the harm of polypharmacy is well documented and researched, there is a lack of evidence on the benefits of, or safety of, deprescribing within a primary care setting. Most of the current evidence on deprescribing are often focused on those with limited life expectancy,69 the very elderly,61 and those in nursing homes.4 As such, further research is needed to determine whether there are any benefits of deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications, especially in the general population and those with multimorbidity. These trials should ideally include patient reported outcomes, such as health-related quality of life, and cost-effectiveness as well as health service use.

Strengths and Limitations

To our best knowledge, this is the first review that collates the growing body of research on deprescribing. We used NIH Checklist to assess the quality of reporting and risk of bias of included studies. This study examined the preference towards deprescribing using validated questionnaires, which has an acceptable validity and reliability. This study has several limitations. This study only included quantitative studies, and thus may lack contextual reasons on the barriers and enablers of deprescribing. Nevertheless, this topic has been well covered by other qualitative reviews to date.20, 57, 58 This review identified limited studies which sought to examine the caregivers’ attitudes towards deprescribing. Further research on caregivers’ opinions on their care recipients’ medication are required to mitigate the gap, as they play a crucial role in managing medications for older adults. Included studies had broad inclusion criteria, for instance participants with multimorbidity and/or frailty (see Table 1). The heterogeneity of information did not allow us to determine whether patients and/or caregivers were more willing to deprescribe any specific class of medicine or medications prescribed by their primary care physician versus a consultant. This can be an area for future deprescribing research, as the information would help clinicians further identify participants who are more amenable to deprescribing.

While the study had a broad inclusion criteria, we may have missed some studies as the area of deprescribing has often been poorly indexed. We did not identify any relevant randomized study that had examined if the caregiver’s attitude were changed after any deprescribing related intervention. This highlights the need for more studies to measure changes in deprescribing preference due to an intervention in the future. Finally, included studies did not include the response rates, and thus the representativeness and validity of responses cannot be ascertained.

CONCLUSION

Considering the preferences of patients and their caregivers during the clinical decision-making process is important to aid in simplifying the complex medical regimens. Our results suggest that patients and their caregivers should be offered an attempt to trial deprescribing, as most had indicated willingness to deprescribe their medication, whenever possible. Nevertheless, healthcare providers need to be mindful to communicate and engage patients and their caregivers during the deprescribing as these tools do not accurately predict the success of deprescribing.

Data availability

All relevant information has been included into the manuscript and in the supporting information. Further information can be requested from the corresponding author.

References

Liew NY, Chong YY, Yeow SH, Kua KP, San Saw P, Lee SWH. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications among geriatric residents in nursing care homes in Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41(4):895-902.

Lee SWH, Chong CS, Chong DWK. Identifying and addressing drug-related problems in nursing homes: an unmet need in Malaysia? Int J Clin Pract. 2016;70(6):512-.

Wastesson JW, Morin L, Tan EC, Johnell K. An update on the clinical consequences of polypharmacy in older adults: a narrative review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2018;17(12):1185-96.

Kua CH, Mak VSL, Huey Lee SW. Health outcomes of deprescribing interventions among older residents in nursing homes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(3):362-72.e11.

Reeve E, Gnjidic D, Long J, Hilmer S. A systematic review of the emerging definition of 'deprescribing' with network analysis: implications for future research and clinical practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(6):1254-68.

Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, Potter K, Le Couteur D, Rigby D, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-34.

Anderson K, Stowasser D, Freeman C, Scott I. Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ open. 2014;4(12):e006544.

De Vries T, Henning RH, Hogerzeil HV, Fresle D, Policy M, Organization WH. Guide to good prescribing: a practical manual: World Health Organization1994.

Hughes TM, Merath K, Chen Q, Sun S, Palmer E, Idrees JJ, et al. Association of shared decision-making on patient-reported health outcomes and healthcare utilization. Am J Surg. 2018;216(1):7-12.

Reeve E, Low LF, Shakib S, Hilmer SN. Development and validation of the revised Patients' Attitudes Towards Deprescribing (rPATD) questionnaire: Versions for older adults and caregivers. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(12):913-28.

Lim JH, Omar MS, Tohit N. Polypharmacy and willingness to deprescribe among elderly with chronic diseases. Int J Geront. 2018;12(4):340-3.

Potter K, Flicker L, Page A, Etherton-Beer C. Deprescribing in frail older people: A randomised controlled trial. PloS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0149984.

Kua C-H, Yeo CYY, Tan PC, Char CWT, Tan CWY, Mak V, et al. Association of deprescribing with reduction in mortality and hospitalization: A pragmatic stepped-wedge cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(1):82-9e3.

Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: A systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(10):793-807.

Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. BMJ Qual Saf. 2005;14(1):26-33.

Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Development and validation of the patients' attitudes towards deprescribing (PATD) questionnaire. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(1):51-6.

Linsky A, Simon SR, Stolzmann K, Meterko M. Patient perceptions of deprescribing: Survey development and psychometric assessment. Med Care. 2017;55(3):306-13.

Linsky AM, Stolzmann K, Meterko M. The patient perceptions of deprescribing (PPoD) survey: Short-form development. Drugs Aging. 2020;37(12):909-16.

Paque K, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M, Pardon K, Dilles T, Deliens L, et al. Barriers and enablers to deprescribing in people with a life-limiting disease: A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2018;33(1):37-48.

Doherty AJ, Boland P, Reed J, Clegg AJ, Stephani A-M, Williams NH, et al. Barriers and facilitators to deprescribing in primary care: a systematic review. BJGP Open. 2020;4(3):bjgpopen20X101096.

National Institutes of Health. Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. 2014. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/cohort Accessed 15th February 2021.

Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5(1):13.

Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(11):974-8.

Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Stat. 1950:607-11.

Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):39.

Edelman M, Jellema P, Hak E, Denig P, Blanker MH. Patients' attitudes towards deprescribing alpha-blockers and their willingness to participate in a discontinuation trial. Drugs Aging. 2019;36(12):1133-9.

Galazzi A, Lusignani M, Chiarelli M, Mannucci P, Franchi C, Tettamanti M, et al. Attitudes towards polypharmacy and medication withdrawal among older inpatients in Italy. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(2):454-61.

Ikeji CA, Brandt N, Hennawi G, Williams A. Patient and prescriber perspectives on proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use and deprescribingin older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(Supplement 1):S287.

Kalogianis MJ, Wimmer BC, Turner JP, Tan ECK, Emery T, Robson L, et al. Are residents of aged care facilities willing to have their medications deprescribed? Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2016;12(5):784-8.

Kua CH, Reeve E, Ratnasingam V, Mak VSL, Lee SWH. Patients' and caregivers' attitudes towards deprescribing in Singapore. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020.

Kua KP, Saw PS, Lee SWH. Attitudes towards deprescribing among multi-ethnic community-dwelling older patients and caregivers in Malaysia: a cross-sectional questionnaire study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41(3):793-803.

Qi K, Reeve E, Hilmer S, Pearson S-A, Matthews S, Gnjidic D, et al. Older peoples' attitudes regarding polypharmacy, statin use and willingness to have statins deprescribed in Australia. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(5):949-57.

Reeve E, Low LF, Hilmer SN. Attitudes of older adults and caregivers in Australia toward deprescribing. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(6):1204-10.

Reeve E, Wiese MD, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Shakib S. People's attitudes, beliefs, and experiences regarding polypharmacy and willingness to deprescribe. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(9):1508-14.

Reeve E, Wolff JL, Skehan M, Bayliss EA, Hilmer SN, Boyd CM. Assessment of attitudes toward deprescribing in older Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1673-80.

Schiotz ML, Frolich A, Jensen AK, Reuther L, Perrild H, Petersen TS, et al. Polypharmacy and medication deprescribing: A survey among multimorbid older adults in Denmark. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2018;6(6):e00431.

Tegegn HG, Tefera YG, Erku DA, Haile KT, Abebe TB, Chekol F, et al. Older patients' perception of deprescribing in resource-limited settings: a cross-sectional study in an Ethiopia university hospital. BMJ open. 2018;8(4):e020590.

Aoki T, Yamamoto Y, Ikenoue T, Fukuhara S. Factors associated with patient preferences towards deprescribing: a survey of adult patients on prescribed medications. Int J Clin Pract. 2019;41(2):531-7.

Gillespie R, Mullan J, Harrison L. Attitudes towards deprescribing and the influence of health literacy among older Australians. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2019;20.

Omar MS, Ariandi AH, Tohit NM. Practical problems of medication use in the elderly Malaysians and their beliefs and attitudes toward deprescribing of medications. J Pharm Pract Res. 2019;8(3):105-11.

Martinez AI, Spencer J, Moloney M, Badour C, Reeve E, Moga DC. Attitudes toward deprescribing in a middle-aged health disparities population. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2020;16(10):1502-7.

Ng WL, Tan MZW, Koh EYL, Tan NC. Deprescribing: What are the views and factors influencing this concept among patients with chronic diseases in a developed Asian community? Proc Singapore Healthc. 2017;26(3):172-9.

Nusair MB, Arabyat R, Al-Azzam S, El-Hajji FD, Nusir AT, Al-Batineh M. Translation and psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the revised Patients' Attitudes Towards Deprescribing questionnaire. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2020;11(2):173-81.

Reeve E, Anthony AC, Kouladjian O'Donnell L, Low LF, Ogle SJ, Glendenning JE, et al. Development and pilot testing of the revised Patients' Attitudes Towards Deprescribing questionnaire for people with cognitive impairment. Australas J Ageing. 2018;37(4):E150-E4.

Sirois C, Ouellet N, Reeve E. Community-dwelling older people's attitudes towards deprescribing in Canada. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2017;13(4):864-70.

Turner JP, Martin P, Zhang YZ, Tannenbaum C. Patients beliefs and attitudes towards deprescribing: Can deprescribing success be predicted? Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2020;16(4):599-604.

Zhang S, Meng L, Yang J, Luo L, Qiu F. Study on attitudes towards deprescribing among elderly patients with chronic diseases in several communities of Chongqing. China Pharmacy. 2018;29(10):1408-11.

Achterhof AB, Rozsnyai Z, Reeve E, Jungo KT, Floriani C, Poortvliet RKE, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication and attitudes of older adults towards deprescribing. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0240463.

Scott S, Clark A, Farrow C, May H, Patel M, Twigg MJ, et al. Attitudinal predictors of older peoples' and caregivers' desire to deprescribe in hospital. BMC Geriatrics. 2019;19(1):108.

Roux B, Sirois C, Niquille A, Spinewine A, Ouellet N, Pétein C, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric validation of the revised patients’ attitudes towards deprescribing (rPATD) questionnaire in French. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2020:In press.

Lundby C, Simonsen T, Ryg J, Søndergaard J, Pottegård A, Lauridsen HH. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation of Danish version of the revised patients’ attitudes towards deprescribing (rPATD) questionnaire: Version for older people with limited life expectancy. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2020:In press.

Linsky A, Simon SR, Stolzmann K, Meterko M. Patient attitudes and experiences that predict medication discontinuation in the Veterans Health Administration. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. 2018;58(1):13-20.

Serrano Giménez R, Gallardo Anciano J, Robustillo Cortés MA, Blanco Ramos JR, Gutiérrez Pizarraya A, Morillo Verdugo R. Beliefs and attitudes about deprescription in older HIV-infected patients: ICARD Project. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2021;34(1):18-27.

Rozsnyai Z, Jungo KT, Reeve E, Poortvliet RKE, Rodondi N, Gussekloo J, et al. What do older adults with multimorbidity and polypharmacy think about deprescribing? The LESS study - a primary care-based survey. BMC Geriatrics. 2020;20(1):435.

Lundby C, Glans P, Simonsen T, Søndergaard J, Ryg J, Lauridsen HH, et al. Attitudes towards deprescribing: The perspectives of geriatric patients and nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2021:1-11.

Ikeji C, Williams A, Hennawi G, Brandt NJ. Patient and provider perspectives on deprescribing proton pump inhibitors. J Gerontol Nurs. 2019;45(10):9-17.

Paque K, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M, Pardon K, Dilles T, Deliens L, et al. Barriers and enablers to deprescribing in people with a life-limiting disease: a systematic review. Palliative medicine. 2019;33(1):37-48.

Lundby C, Graabaek T, Ryg J, Sondergaard J, Pottegard A, Nielsen DS. Health care professionals' attitudes towards deprescribing in older patients with limited life expectancy: A systematic review. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 2019;85(5):868-92.

Howard DH, Sentell T, Gazmararian JA. Impact of health literacy on socioeconomic and racial differences in health in an elderly population. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):857-61.

Tang C, Wu X, Chen X, Pan B, Yang X. Examining income-related inequality in health literacy and health-information seeking among urban population in China. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):221.

Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K, Schwartz D, Etherton-Beer CD. The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(3):583-623.

Thio SL, Nam J, Van Driel ML, Dirven T, Blom JW. Effects of discontinuation of chronic medication in primary care: A systematic review of deprescribing trials. BJGP. 2018;68(675):e663-e72.

Reeve E, Thompson W, Farrell B. Deprescribing: A narrative review of the evidence and practical recommendations for recognizing opportunities and taking action. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;38:3-11.

Reeve E, Low LF, Hilmer SN. Beliefs and attitudes of older adults and carers about deprescribing of medications: A qualitative focus group study. British Journal of General Practice. 2016;66(649):e552-e60.

Pouliot A, Vaillancourt R. Medication literacy: Why pharmacists should pay attention. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2016;69(4):335-6.

Chen L, Farrell B, Ward N, Russell G, Eisener-Parsche P, Dore N. Discontinuing benzodiazepine therapy: An interdisciplinary approach at a geriatric day hospital. Can Pharm J. 2010;143(6):286-95.e3.

Linsky A, Meterko M, Bokhour BG, Stolzmann K, Simon SR. Deprescribing in the context of multiple providers: Understanding patient preferences. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(4):192-8.

Kutner JS, Blatchford PJ, Taylor DH, Jr., Ritchie CS, Bull JH, Fairclough DL, et al. Safety and benefit of discontinuing statin therapy in the setting of advanced, life-limiting illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):691-700.

Narayan S, Nishtala P. Discontinuation of preventive medicines in older people with limited life expectancy: A systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2017;34(10):767-76.

Kua KP, Saw PS, Lee SWH. Attitudes towards deprescribing among multi-ethnic community-dwelling older patients and caregivers in Malaysia: a cross-sectional questionnaire study. A Comment. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41(5):1131-2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: S. W. H. L.

Data curation: Y. L. C., Y. L. W., S. L. G., K. W. T., S. W. H. L.

Formal analysis: S. W. H. L.

Methodology: Y. L. C., Y. L. W., S. L. G., K. Y. N., S. W. H. L.

Supervision: S. W. H. L.

Writing—original draft: Y. L. C., Y. L. W., S. L. G., S. W. H. L.

Writing—review and editing: Y. L. C., Y. L. W., S. L. G., K. W. T., K. Y. N., S. W. H. L.

S. W. H. L. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 871 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chock, Y.L., Wee, Y.L., Gan, S.L. et al. How Willing Are Patients or Their Caregivers to Deprescribe: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 3830–3840 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06965-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06965-5