Abstract

Background

Given persistent gaps in coordination of care for medically complex primary care patients, efficient strategies are needed to promote better care coordination.

Objective

The Coordination Toolkit and Coaching project compared two toolkit-based strategies of differing intensity to improve care coordination at VA primary care clinics.

Design

Multi-site, cluster-randomized QI initiative.

Participants

Twelve VA primary care clinics matched in 6 pairs.

Interventions

We used a computer-generated allocation sequence to randomize clinics within each pair to two implementation strategies. Active control clinics received an online toolkit with evidence-based tools and QI coaching manual. Intervention clinics received the online toolkit plus weekly assistance from a distance coach for 12 months.

Main Measures

We quantified patient experience of general care coordination using the Health Care System Hassles Scale (primary outcome) mailed at baseline and 12-month follow-up to serial cross-sectional patient samples. We measured the difference-in-difference (DiD) in clinic-level-predicted mean counts of hassles between coached and non-coached clinics, adjusting for clustering and patient characteristics using zero-inflated negative binomial regression and bootstrapping to obtain 95% confidence intervals. Other measures included care coordination QI projects attempted, tools adopted, and patient-reported exposure to projects.

Key Results

N = 2,484 (49%) patients completed baseline surveys and 2,481 (48%) completed follow-ups. Six coached clinics versus five non-coached clinics attempted QI projects. All coached clinics versus two non-coached clinics attempted more than one project or projects that were multifaceted (i.e., involving multiple components addressing a common goal). Five coached versus three non-coached clinics used 1–2 toolkit tools. Both the coached and non-coached clinics experienced pre-post reductions in hassle counts over the study period (− 0.42 (− 0.76, − 0.08) non-coached; − 0.40 (− 0.75, − 0.06) coached). However, the DiD (0.02 (− 0.47, 0.50)) was not statistically significant; coaching did not improve patient experience of care coordination relative to the toolkit alone.

Conclusion

Although coached clinics attempted more or more complex QI projects and used more tools than non-coached clinics, coaching provided no additional benefit versus the online toolkit alone in patient-reported outcomes.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03063294

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Inefficiencies in care coordination contribute to wasted healthcare services and frustration for patients,1,2 even within care models that include a coordination focus such as the patient-centered medical home (PCMH).3,4,5,6 As the largest US integrated healthcare system, the Veterans Health Administration (VA) faces unique challenges in coordinating care. In 2010, the VA began implementing a PCMH model called Patient-Aligned Care Teams (PACT), in which a primary care provider, registered nurse, licensed practical/vocational nurse, and clerk coordinate VA health services across a continuum of settings.7 While the majority of specialist consults from PACT (either virtual or in person) are to VA-affiliated specialists, VA also coordinates services delivered to its enrollees by non-VA providers (e.g., through Medicare, or VA-purchased care).8,9 Despite implementation of PACT and other strategies to support effective care delivery, optimal care coordination has remained elusive for the VA,10 similar to other healthcare organizations.

Improving care coordination is challenging because implementation strategies must address complex sets of activities that cannot be reduced to a particular evidence-based practice. Furthermore, published research on specific care coordination practices shows that while care coordination can be improved,11 coordination problems and outcomes can vary substantially depending on local context.10 Care coordination improvement initiatives that can adapt to local practice environments, while benefiting from evidence-based approaches, are needed.

Toolkits (collections of individual tools addressing a given problem) have been identified as a critical element for spreading evidence-based care into routine practice.12 Toolkits have proliferated over the past decade, especially since online deployment has provided a relatively inexpensive way to make quality improvement (QI) tools readily accessible. Evidence, however, is lacking on the benefits of toolkits in primary care. Furthermore, passive online approaches without additional support may be insufficient to promote tool uptake in QI initiatives.13,14 In addition, toolkit contents may vary in quality and applicability to specific settings.

Recent research suggests that an external practice facilitator or “coach” can enhance the active use of toolkits by providing tailored assistance.15 Practice facilitation is a multifaceted strategy commonly used in primary care settings that involves engaging QI-trained individuals in supporting implementation of evidence-based care guidelines.16,17,18,19,20 Distance coaching, a form of practice facilitation, extends the model to virtual modalities, increasing scalability.21

In the Coordination Toolkit and Coaching (CTAC) project, we systematically identified and rated tools for supporting local care coordination QI by primary care sites. We then developed an online toolkit, made it available on the VA Intranet,22 and compared two implementation strategies of different intensity to support VA primary care clinics in improving care coordination quality. Six pairs of participating clinics were randomly assigned to either a lower-intensity strategy consisting of online toolkit dissemination with minimal support, or a higher-intensity strategy combining the online toolkit with distance coaching. We judged the relative effectiveness of the two strategies based on patient experience of general care coordination using a validated questionnaire administered at baseline and 12-month follow-up. Secondarily, we described the number and types of care coordination QI projects attempted and the tools used by the coached and non-coached clinics.

METHODS

Approach and Participating Clinics

CTAC, a multi-site, cluster-randomized controlled QI initiative, was determined to be non-research by the VA Office of Patient Care Services and the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System’s Institutional Review Board. We recruited and enrolled VA primary care clinics from October 2016 to June 2018 using a multi-pronged approach, including teleconference presentations and direct outreach to regional and national leadership. Pairs of VA primary care clinics within the same VA regional medical centers and with similar panel sizes, number of teams, and offered services were eligible.

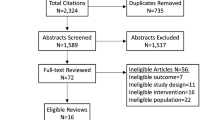

Six pairs of primary care clinics (n = 12) met inclusion criteria and agreed to participate (Fig. 1).23 All clinics were urban based on RUCA codes,24 and located in geographically diverse US Census Divisions.25 Clinics ranged in size from large (13–19 providers) to very small (1–2 providers). The clinics’ PACT Implementation Progress Index, an annual VA measure of PCMH implementation associated with better quality of care,26 indicated PCMH implementation in the middle range of effectiveness.27 The project statistician, blinded to clinic characteristics, used a computer-generated allocation sequence to randomize clinics within each pair to the two implementation strategies.

Interventions

Online CTAC Toolkit and Initial Project Engagement

To create an online care coordination toolkit, we systematically identified and rated available tools for inclusion.22 The final online toolkit comprised 18 care coordination tools in five categories: managing referrals to specialty care, medication management, patient after-visit summary, patient activation materials, and provider contact information for patients (Table 1).22 The toolkit provides details about the resources required and expected benefits of each tool, the CTAC QI coaching manual, and a webinar orienting users to the toolkit.22

After facility directors approved participation, we scheduled initial phone-based “priority-setting” meetings with leadership of all enrolled clinics to review the project scope and timeline. We described the implementation strategies, presented clinic staff survey and readiness interview results (not reported here), discussed local care coordination priorities, introduced the online toolkit, and brainstormed QI project ideas. We explicitly told clinics that projects were not required to utilize a tool from the toolkit.

Lower-Intensity Strategy for Non-Coached Clinics

Immediately after the priority-setting meetings, we sent emails to the non-coached clinics that included their randomization assignment, their baseline patient experience survey data, and the link to the CTAC toolkit’s webpage.28 The email also instructed the non-coached clinics to choose a project champion and a proposed QI project and then email this information back to the CTAC project coordinator. The non-coached sites received no further guidance or assistance from project staff during the 12-month intervention period.

Higher-Intensity, Distance Coaching Strategy

The email sent to the coached clinics also included randomization assignment, baseline patient experience survey data, and a link to the CTAC toolkit webpage. The message additionally asked clinics to schedule an in-person 4-h site visit and select a local project champion and team to participate.

The CTAC team included two trained QI coaches with prior clinical experience, each assigned to three of the six coached clinics. Coaching training included shadowing experienced facilitators, and the larger team supported the coaches with weekly calls to discuss coaching challenges and project roadblocks. During the 4-h site visit, the CTAC team introduced the clinic’s assigned distance coach, explained the plan for distance coaching (by phone and virtual screen-sharing platform), and facilitated discussion of possible QI project topics.

Over a 12-month period, the coaches helped clinic teams develop and implement care coordination QI projects, facilitating weekly hour-long coaching calls and communicating with team members as needed between scheduled sessions to maintain momentum and accountability. Within the first 3 months, the coaches helped each clinic develop action plans with relevant Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Time-bound (SMART) goals,29 and suggested relevant tools from the toolkit. The coaches provided technical support in QI techniques, project management, evaluation, and data collection; they also led monthly collaborative calls with coached clinics to encourage cross-site learning.

Main Measures and Sources

QI Projects

To identify the number and type of QI projects that clinics attempted and tools that were used, the project manager created preliminary lists using action plans and final project reports for the coached clinics and the initial report emailed by the non-coached clinics. Coached clinic lists were verified by the coaches. We also conducted semi-structured interviews at 6-, 12-, and 18-month follow-up with the champions of both non-coached and coached clinics. Using transcripts from these interviews and the final reports from the coached clinics, an evaluator who was uninvolved in intervention activities (LP—medical anthropologist) adapted the project manager’s preliminary lists to include details about QI projects attempted by clinic teams, as well as any tools that were selected, adapted, or created for the projects.

Patient-Reported Measures

We collected our primary outcome and patient characteristics by surveys mailed to serial cross-sections of Veterans selected from participating clinics at baseline and 12-month follow-up. Because frequent users of primary care are more likely to have multimorbidity, require greater care coordination, and experience greater healthcare system hassles,30,31 our sample included only patients with four or more primary care visits to their assigned clinic during the preceding 12 months, based on data from the VA’s Corporate Data Warehouse.23 Patients were not offered an incentive to participate. Of the invited Veterans, 2,484 (49%) and 2,481 (48%) returned surveys at baseline and follow-up, respectively (see Supplementary Appendix for details about participating clinics, survey methodology, and sample, and Fig. 1 for response rates by study arm).

The primary outcome was improvement in patient-reported experience assessed with the 16-item Health Care System Hassles Scale.30 Recognized as a measure of care coordination,32 the Hassles questionnaire lists problems that patients may encounter with their general healthcare, as opposed to their care experience with one specific visit or provider.30 The questionnaire prompts patients to indicate how much situations such as “lack of information about why you’ve been referred to a specialist” have been a problem, using a 5-point scale ranging from 0 to 4. Ratings were dichotomized (0 = “Not a problem at all” vs. 1 = any level of problem indicated) and summed to yield a hassles count ranging from 0 to 16, with higher scores indicating more hassles.30

Because we allowed clinics to pursue projects of their own choosing that addressed salient care coordination problems, we were not able to identify a process measure a priori that would universally apply to all clinics. Therefore, we developed supplemental questions for the follow-up patient survey that were tailored to the initial project(s) undertaken by the coached clinic in each clinic pair.

Covariates assessed by the surveys included sociodemographic characteristics (sex, age group, race/ethnicity, education, and marital status) and ratings of overall physical and mental health status using single items adapted from the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 (MOS SF-36).33 Patients were also asked to report their source of healthcare in the past 12 months (e.g., VA healthcare providers only or both VA and non-VA providers).23

Quantitative Analysis

We computed descriptive statistics for patient-reported characteristics and compared the intervention arms at baseline using bivariate statistics. We calculated total Hassles counts after using hot deck multiple imputation for missing values only if individuals responded to at least 13 of the 16 items comprising the scale. Multivariate difference-in-difference (DiD) analysis was used to determine the difference between coached and non-coached clinics in the change in patient-reported hassles from baseline to 12-month follow-up. Because of the number of zero scores (i.e., no hassles) noted in the Hassles count data, we used zero-inflated negative binomial regression (ZINB)34,35 to calculate predicted mean hassles at baseline and follow-up for each clinic after controlling for factors that might confound the relationship between the exposure (coaching) and the outcome (hassles). ZINB analyses were conducted using Stata/SE15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).36 We calculated DiD point estimates and generated associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for coached and non-coached arms for each time point using a bootstrap procedure. We used two models for the DiD. The base model adjusted for clinic fixed effects and clustering of survey responses within clinics. The full model included the base model and adjusted for patient characteristics. We conducted post hoc analyses of the supplemental questions included in the follow-up surveys, using the chi-square test to compare the proportion of patients from coached versus non-coached clinics within each pair who reported being exposed to the coached clinic’s patient-facing QI project components.

RESULTS

QI Projects and Tools

Table 2 describes QI projects attempted and tools used by the coached and non-coached clinics. All six coached clinics versus two non-coached clinics attempted more than one project or projects that were multifaceted. However, both coached and non-coached clinics primarily pursued projects that teams could implement by themselves without additional support or policy changes. All six coached clinics and five of the non-coached clinics attempted QI projects on the following topics: walk-ins (project n = 5), medications (n = 2), prediabetes (n = 1), diabetes (n = 1), extended clinic hours (n = 1), specialty consult discontinuation (n = 1), patient self-management (n = 1), and no-shows (n = 1). The sixth non-coached clinic chose a champion and selected a project topic on access, but never initiated a project. Of the eleven clinics that attempted projects, eight (five coached versus three non-coached) used one or more of the following three tools from the toolkit (Table 2): Clinic Information Brochure, Save a Trip to Primary Care, and Medication Tracker. The three other clinics (one coached versus two non-coached) either adapted other tools and/or created their own tool.

Chi-square analysis of the supplemental process questions tailored to coached clinics’ QI projects indicates that two of six coached clinics had significantly higher proportions of patients who reported receiving patient brochures than their counterparts in paired non-coached clinics (Table 3), indicating greater awareness of the patient-facing aspects of the coached QI projects.

Patient-Reported Hassles

The number of hassles patients reported at baseline ranged from 0 to 16. Seventy-nine percent of Veterans reported experiencing one or more hassles (median 4; interquartile range 1–8). The top five hassles were having to wait a long time for an appointment with specialty providers or clinics (56%), poor communication between different healthcare providers (44%), lack of information about treatment options (41%), lack of information about medical conditions (40%), and difficulty getting questions answered or getting medical advice between scheduled appointments (40%).23 Non-coached clinics had significantly more patient-reported hassles than coached clinics at baseline (mean 5.25 (SD 4.85) vs. mean 4.62 (SD 4.51), respectively; p < 0.001).

Multivariate Analysis

Table 4 presents the unadjusted and adjusted means at baseline and follow-up, mean differences, and DiD in Hassles scores and their corresponding 95% CIs for the non-coached and coached clinics. Both the coached and non-coached clinics experienced pre-post reductions in hassle counts over the course of the study period (− 0.42 (− 0.76, − 0.08) for non-coached and − 0.40 (− 0.75, − 0.06) for coached). However, the DiD (0.02 (− 0.47, 0.50)) was not statistically significant; i.e., there was insufficient evidence that coaching could improve patient experience of care coordination. Because 260 participants had longitudinal data (i.e., at both baseline and at follow-up), we conducted two sensitivity analyses: one that excluded these participants and another that only used these participants. Both yielded results similar to those found with the entire sample (see Supplementary Appendix).

DISCUSSION

In our analysis comparing a lower-intensity care coordination intervention using an online toolkit with a higher-intensity intervention involving both the online toolkit and distance coaching, we found that the frequency of patient-reported hassles improved in both groups to a similar extent. This general improvement could reflect the implementation strategies employed by CTAC at both coached and non-coached clinics (e.g., leadership engagement, requiring the nomination of a champion, feedback of baseline patient experience survey results, and provision of the toolkit with coaching manual). Since our study did not include a “usual care” control group, we do not know whether the observed improvements were the result of the intervention versus secular trends unrelated to the interventions.

During CTAC, all six coached and five of the six non-coached clinics attempted one or more QI projects. Although coached clinics attempted more complex QI activities and incorporated more tools from the toolkit than non-coached clinics, this did not translate to a differential improvement in patient experience for coached clinics. Clinics were explicitly told that they were not required to use a tool from the toolkit. Accordingly, one coached clinic and two non-coached clinics either created their own tool or adapted other tools for their QI projects. Three tools in the CTAC toolkit were used regularly, within two domains: Provider Contact Information for Patients and Medication Management. Five clinics incorporated tools from the first domain into care coordination QI projects designed to reduce unnecessary walk-ins. These were relevant to one of the most frequent patient-reported baseline hassles (i.e., difficulty getting questions answered or getting medical advice between scheduled appointments). QI projects using these tools were feasible to implement without additional personnel, resources, or policy changes. More challenging problems for which the toolkit provided tools, such as coordination of referrals across primary care and specialty settings, were not pursued by either coached or non-coached clinics.

Our analysis has several limitations. First, our analytic approach assumed similar time-dependent secular trends in patient experience between the study groups.37 Because patient experience measurements used different cohorts at the two time points, we cannot verify the validity of this assumption. Second, patient experience measures were imbalanced at baseline, with non-coached clinics reporting more hassles. This could lead to increased opportunity for hassles to improve over time in non-coached clinics, biasing results in favor of non-coached clinics. Third, because participation in CTAC was not mandated, participating clinics might have been more highly engaged than average, such that findings may not generalize to VA primary care nationwide. Finally, the total hassles count reflecting overall patient experience may not have been sensitive to changes resulting from specific QI projects.

In conclusion, both coached and non-coached CTAC clinics achieved similar improvements in patient-reported hassles in the context of ongoing national VA efforts to improve primary care quality. These results are consistent with systematic reviews showing that both toolkits and practice facilitation can be effective in implementing guideline-concordant care processes.14,18,20 This may be especially true for complex challenges associated with care coordination, which cannot be reduced to a specific set of care processes. While the addition of higher-intensity coaching did not improve patient experience more than lower-intensity toolkit dissemination alone, recent work has shown other benefits of distance coaching, such as sustainment of complex interventions and skill mastery.21,38 Ongoing CTAC analyses are examining whether distance coaching enhanced team functioning or completion and spread of QI projects, while future work should explore the optimal bundle of implementation strategies and tools to improve patient experience of care coordination. Our current findings suggest that most clinics making a commitment to do so will engage in care coordination QI activities when given access to an online toolkit supported by lower-intensity implementation strategies. Although higher-intensity coaching may not be needed in all circumstances, it may encourage the pursuit of more complex QI projects.

References

Smith ML, Bergeron CD, Adler CH, et al. Factors associated with healthcare-related frustrations among adults with chronic conditions. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(6):1185-1193.

Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US Health Care System: Estimated Costs and Potential for Savings. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-1509.

Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL, et al. Primary care practice transformation is hard work. Med Care. 2011;49 Suppl: S28-S35.

Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, et al. The patient-centered medical home: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):169-178.

Friedberg MW, Schneider EC, Rosenthal MB, et al. Association between participation in a multipayer medical home intervention and changes in quality, utilization, and costs of care. JAMA. 2014;311(18):815-825.

Tung EL, Gao Y, Peek ME, et al. Patient experience of chronic illness care and medical home improvement in safety net clinics. Health Ser Res. 2018;53(1):469-488.

Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013 Jul 1;19(7):e263–272.

Gellad WF. The Veterans Choice Act and dual health system use. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(2):153-154.

Congressional Research Service. H.R. 5674 (115th): VA MISSION Act of 2018. Available at https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/115/hr5674/summary. Accessed April 18, 2021.

Kilbourne AM, Hynes D, O'Toole T, et al. A research agenda for care coordination for chronic conditions: aligning implementation, technology, and policy strategies. Transl Behav Med. May 2018;8(3):515-521. https://academic.oup.com/tbm/article/8/3/515/5001942.

Powell Davies G, Williams AM, Larsen K, Perkins D, Roland M, Harris MF. Coordinating primary health care: an analysis of the outcomes of a systematic review. Med J Aust. 2008;188(8 Suppl):S65–8.

Hempel S, O’Hanlon C, Lim YW, Danz M, Larkin J, Rubenstein L. Spread tools: a systematic review of components, uptake, and effectiveness of quality improvement tools. Implement Sci. 2019;14:83. https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-019-0929-8.

Yamada J, Shorkey A, Barwick M, Widger K, Stevens BJ. The effectiveness of toolkits as knowledge translation strategies for integrating evidence into clinical care: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e006808. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/5/4/e006808.

Gold R, Bunce A, Cowburn S, et al. Does increased support improve community clinics’ guideline concordant care? Results of a mixed methods, pragmatic comparative effectiveness trial. Implement Sci. 2019;14.100. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13012-019-0948-5.

Mabachi NM, Cifuentes M, Barnard J, et al. Demonstration of the Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit: Lessons for quality improvement. J Ambul Care Manage. 2016;39(3):199-208.

Lemelin J, Hogg W, Baskerville NB. Evidence to action: a tailored multifaceted approach to changing family physician practice patterns and improving preventive care. CMAJ. 2001;164(6):757-63.

Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Aspy CB. Practice facilitators: a review of the literature. Fam Med. 2005;37(8):581-588.

Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg W. Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:63-74.

Cranley LA, Cummings GG, Profetto-McGrath J, Toth F, Estabrooks CA. Facilitation roles and characteristics associated with research use by healthcare professionals: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e014384. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/7/8/e014384.long.

Wang A, Pollack T, Kadziel LA, et al. Impact of practice facilitation in primary care on chronic disease care processes and outcomes: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(11):1968-77.

Bhat A., Bennett IM, Bauer AM, et al. Longitudinal Remote Coaching for Implementation of Perinatal Collaborative Care: A Mixed-Methods Analysis. Psychiatric Ser. 2020; 71:518–521. https://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.11176/appi.ps.201900341.

Ganz DA, Barnard JM, Smith NZY, et al. Development of a web-based toolkit to support improvement of care coordination in primary care. Transl Behav Med. 2018;8(3):492-502. https://academic.oup.com/tbm/article/8/3/492/5001928.

Noël PH, Barnard JM, Barry FM, et al. Patient experience of healthcare system hassles: Dual-system vs single-system users. Health Ser Res. 2020;55(4):548-555.

United States Department of Agriculture. Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. Available from https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes.aspx. Accessed September 28, 2020.

United States Census Bureau. Regions and Divisions with State FIPS Codes. Available from https://www2.census.gov/geo/docs/maps-data/maps/reg_div.txt. Accessed September 5, 2020.

Nelson KM, Helfrich C, Sun H, et al. Implementation of the patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration: associations with patient satisfaction, quality of care, staff burnout, and hospital and emergency department use. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1350-8.

Olmos Ochoa TT, Bharath P, Ganz DA, et al. Pact a de-facto “Hub” for Care Coordination in VA: Staff perspectives from the Coordination Toolkit and Coaching (CTAC) Project. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(Suppl):82-9.

The Coordination and Coaching Toolkit. Available at https://vaww.visn10.portal.va.gov/sites/Toolkits/toolkit/Pages/Tool-List.aspx. Accessed September 27, 2020.

Doran GT. There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives. Manage Rev. 1981;70(11):35–6.

Parchman ML, Noël PH, Lee S. Primary care attributes, health care system hassles, and chronic illness. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1123–9.

Zulman DM, Pal Chee C, Wagner TH, et al. Multimorbidity and healthcare utilization among high-cost patients in the US Veterans Affairs Health Care System. BMJ Open. 2015;5: e007771. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content5/4/e007771.long.

McDonald KM, Schultz E, Albin L, et al. Care Coordination Atlas, Version 4. AHRQ Publication No. 14-0037- EF. June 2014. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. June 2014. Available at https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/ccm_atlas.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2020.

Ware JE Jr. Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473-483.

McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized Linear Models. 2nd ed. London: Chapman and Hall; 1989.

Neelon B, O'Malley AJ, Smith V. Modeling zero-count and semicontinuous data in health services research Part 1: background and overview. Stat Med. 2016;35(27):5070-5093.

Stata 13 Base Reference Manual. College Station, Tx: Stata Press; 2013.

Ryan AM, Kontopantelis E, Linden A, Burgess JF Jr. Now trending: Coping with non-parallel trends in difference-in-differences analysis. Stat Methods Med Res. 2019 Dec;28(12):3697-3711. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280218814570. Epub 2018 Nov 25.

McDonnell MM, Elder NC, Stock R, Wolf M, Steeves-Reece A, Graham T. Project ECHO integrated within the Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network (ORPRN). J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:789-795.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge technical assistance from Nicholas Jackson, PhD, and Frances Barry, MA.

Funding

This material is based on work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative through a grant to the Care Coordination QUERI Program (QUE 15-276). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. Additional support was provided by NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) UCLA CTSI Grant Number UL1TR001881.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors report support from one or more of the following during the conduct of the study: VA QUERI, VA HSR&D, National Institutes of Health, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, VA Office of Primary Care, Enhancing Tools and Resources to Improve Coordination of VA Primary Care: A Research to Impact for Veterans (RIVR) Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Department of Defense, Administration on Community Living, and WellMed Charitable Foundation.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations

Ganz D, Penney L, Noël PH, Olmos-Ochoa T, Chawla N. The influence of facilitation on care coordination in VA primary care: Evaluation of the CTAC quality improvement project. VA Health Services Research & Development Cyberseminar. 4/15/2020. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=3792.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 64 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Noël, P.H., Barnard, J.M., Leng, M. et al. The Coordination Toolkit and Coaching Project: Cluster-Randomized Quality Improvement Initiative to Improve Patient Experience of Care Coordination. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 95–103 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06926-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06926-y