Abstract

Background

In response to the opioid epidemic, many states have enacted policies limiting opioid prescriptions. There is a paucity of evidence of the impact of opioid prescribing interventions in primary care populations, including whether unintended consequences arise from limiting the availability of prescribed opioids.

Objective

Our aim was to compare changes in opioid overdose and related adverse effects rate among primary care patients following the implementation of state-level prescribing policies.

Design

A cohort of primary care patients within an interrupted time series model.

Participants

Electronic medical record data for 62,776 adult (18+ years) primary care patients from a major medical center in Vermont from January 1, 2016, to June 30, 2018.

Interventions

State-level opioid prescription policy changes limiting dose and duration.

Main Measures

Changes in (1) opioid overdose rate and (2) opioid-related adverse effects rate per 100,000 person-months following the July 1, 2017, prescription policy change.

Key Results

Among primary care patients, there was no change in opioid overdose rate following implementation of the prescribing policy (incidence rate ratio; IRR: 0.64, 95% confidence interval; CI: 0.22–1.88). There was a 78% decrease in the opioid-related adverse effects rate following the prescribing policy (IRR: 0.22, 95%CI: 0.09–0.51). This association was moderated by opioid prescription history, with decreases observed among opioid-naïve patients (IRR: 0.18, 95%CI: 0.06–0.59) and among patients receiving chronic opioid prescriptions (IRR: 0.17, 95%CI: 0.03–0.99), but not among those with intermittent opioid prescriptions (IRR: 0.51, 95%CI: 0.09–2.82).

Conclusions

Limiting prescription opioids did not change the opioid overdose rate among primary care patients, but it reduced the rate of opioid-related adverse effects in the year following the state-level policy change, particularly among patients with chronic opioid prescription history and opioid-naïve patients. Limiting the quantity and duration of opioid prescriptions may have beneficial effects among primary care patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of prescription opioid-related deaths increased 5- to 10-fold between 1999 and 2016, driven by a number of factors including physician opioid prescribing practices.1,2,3 In the 1990s, pain was proposed as “the fifth vital sign,” and inadequate pain relief was considered poor care.4,5,6,7 This widespread use of opioids to treat chronic non-malignant pain2 resulted in adult primary care clinicians prescribing nearly half of all dispensed opioids by 2012.8 Responses to the opioid epidemic, therefore, posit that reducing opioid prescriptions from primary care practitioners (PCP) might reduce overdoses and adverse effects.9

State-level policies have emerged to reduce opioid prescribing by practitioners.10 Vermont’s policy limited the dose and duration of new opioid prescriptions based on pain severity, requiring prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) checks.10 Following the implementation of this policy, opioid prescriptions decreased11,12,13 and primary care patients who had received prescribed opioids may have experienced abrupt discontinuation or reduced opioid availability.14 As a result, some patients may have accessed illicit opioids of unpredictable potency. Such a switch could introduce unintended consequences, overdoses, or other adverse effects requiring hospitalization.15 Such effects might differ by history of prescription opioids. Opioid-naïve patients may be less impacted by prescription limits since they likely require a short-term prescription for a new painful condition. Patients who receive opioids intermittently may have pain syndromes that are inadequately managed or may seek prescriptions from multiple sources,16,17 while patients with chronic opioid prescriptions may be at greatest risk for negative outcomes if they experience abrupt reduction or cessation.

Using medical record data of primary care patients, we investigated the impacts of statewide policies intended to limit access to prescription opioids in Vermont. Specifically, we sought to (1) assess changes in opioid overdose and related adverse effects rate before and after prescription policy implementation and (2) determine whether opioid overdose and related adverse effects rate differed by history of opioid prescription.

METHODS

Study Setting

A 562-bed academic medical center with ambulatory care practices located within Vermont, providing surgical and medical care, including eleven primary care practice locations. This medical center and its affiliates deployed an integrated electronic medical record (EMR) across all its inpatient and outpatient sites, including the emergency department, in October 2010.18

Study Design

We used an interrupted time-series approach to estimate the effect of Vermont’s policy, comparing opioid overdose and adverse effects rate after vs. before the policy among the adult primary care population. Vermont’s policy, effective July 2017, limited new opioid prescriptions to <5 days for moderate/severe pain and <7 days for extreme pain, restricted long-acting opioids for acute pain, required patient signed informed consent, and mandated PDMP checks.10 Although Vermont’s PDMP was in operation since January 2009, this policy newly mandated that prescribers check the system on initiation and maintenance of opioids for any prescription >10 pills. The Vermont Department of Health publishes data analytics and surveillance of opioid prescriptions, with information from Vermont-licensed pharmacies. This allows the Commissioner of Health to examine prescriber trends statewide. Although individual prescribers and health systems may vary in adherence to checking the PDMP, this system provides additional prescribing transparency. We analyzed EMR data between January 1, 2014, and June 30, 2018. We defined three periods for our analyses: lead-in (January 1, 2014–December 31, 2015), pre-policy (January 1, 2016–June 30, 2017), and post-policy (July 1, 2017–June 30, 2018).

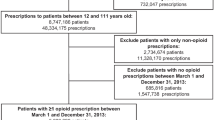

Study Population

Initial data extraction from the EMR included 99,222 patients >18 years listing a medical center physician at registration or most recent encounter as their PCP between October 1, 2010, and June 30, 2018 (Fig. 1). Excluded patients had no primary care office visit (Supplemental Table 1) during the original date range or no encounter between the start of the lead-in period and the end of the post-policy period. We also excluded patients that had no Vermont zip code, were <18 years, or were deceased at the start of the pre-policy period. These exclusions resulted in a cohort of 70,699 primary care patients between January 1, 2014, and June 30, 2018. We further limited our study sample to 62,776 patients having at least one encounter within the EMR during the 2-year lead-in period to ensure our sample had a history of care within the medical center prior to the start of the pre-period (to examine opioid prescription history); 46,635 of these patients had at least one visit post-policy. The University of Vermont Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Exposure

We used EMR documentation of prior medications and new prescriptions (Supplemental Table 1) to investigate the moderating effects of prior opioid prescription use. We classified patient’s opioid prescription history as chronic, intermittent, or none in the lead-in period using a standard definition of morphine equivalents19 and episodes to define chronicity.17,19,20 An episode started with the first opioid prescription without any additional prescriptions in the preceding six months and ended with the final prescription without any additional prescriptions in the following six months, plus the duration of the opioid supply provided by that final prescription. Chronic opioid prescription history was defined as ≥10 prescriptions that year or episodes ≥90 days with ≥120 days of opioid supply dispensed. “Intermittent” opioid prescription history was defined as ≥1 to <10 prescriptions that year or an episode <90 days with ≥1 to <120 days dispensed.17 We defined “none” as no prescriptions in the lead-in period.

Outcomes

Our outcomes were opioid overdose (i.e., poisoning) and opioid-related adverse effects, i.e., other symptoms such as sedation, respiratory depression,21,22 or opioid-induced bowel dysfunction, characterized by constipation, nausea, reflux, vomiting, bloating, or anorexia. Our measures were (1) opioid overdose rate (number of opioid overdoses per 100,000 person-months) and (2) opioid-related adverse effects rate (number of adverse effects per 100,000 person-months). Opioid overdose included ICD-10-CM codes for overdose from heroin, opium, methadone, synthetic and unspecified narcotics, and other opioids and narcotics. Opioid-related adverse effects included ICD-10-CM codes for adverse effects related to opium, methadone, synthetic and unspecified narcotics, and other opioids and narcotics (Supplemental Table 1).

To calculate the rate of each outcome, we created an event for each hospital encounter. We merged the events if the discharge date was within 1 day of the next event admission date. We calculated opioid overdose and adverse effects rate by counting the number of events per patient in each month. Based on conversations with emergency department physicians indicating common use of ICD-10-CM coding, we added “any unspecified drug overdose” (ICD-10-CM: T50.901-4) to our opioid overdose outcome, and “any unspecified drug adverse effect” (ICD-10-CM: T50.905) to our adverse effects outcome as part of sensitivity analyses detailed below.

Data Analysis

For our primary analyses, we used mixed-effects Poisson regression models clustered at the patient level to account for correlation. We applied an interrupted time series framework to examine the changing rate over time for each outcome: (1) opioid overdose and (2) opioid-related adverse effects. We compared our outcomes in the pre-policy period to those of the post-policy period and assessed whether there were significant changes in slopes over time or changes to the level of the rate immediately following the policy change. Secondary analyses examined the moderating effect of opioid prescription history (chronic, intermittent, and none) using stratified analyses. As sensitivity analyses, we re-ran the above models including unspecified drug overdoses and unspecified adverse effects codes, to test the sensitivity of our models to a broader range of diagnosis codes to identify a possible opioid overdose or opioid-related adverse effects, with results presented in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3. Cleaning and data preparation used R version 3.5.123 and analyses used Stata version 15.24 Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Table 1 details demographics and prescription opioid history for the study sample of 62,776 adult primary care patients and for those with opioid events (overdose or adverse effects). The majority of the sample was female, commercially insured, >65 years, and had no prescription opioid history.

Opioid Overdose and Adverse Effects

We present the opioid overdose and adverse effects rate over time allowing for an interruption in the trend to occur July 1, 2017, the start of the new prescription policy (Fig. 2). Quarterly opioid overdose rate ranges between 3.3 and 8.5 overdoses per 100,000 person-months before the policy change and ranges between 0.5 and 4.3 overdoses per 100,000 person-months after the policy change. Quarterly opioid-related adverse effects rate data range between 7.5 and 15.0 adverse effects per 100,000 person-months before the policy change and between 1.6 and 6.5 adverse effects per 100,000 person-months after the policy change.

When assessing opioid overdoses, our results suggest no change in slope of opioid overdoses over time comparing pre to post-policy (time post- vs. pre-policy; P=0.38), as well as no difference in the level of the rate of opioid overdoses immediately following the policy change (policy indicator; P=0.42; Table 2). In the interrupted times series analysis for opioid-related adverse effects, our results suggest no change in slope of adverse effects over time comparing pre- to post-policy (P=0.53), but there is a statistically significant 78% decrease in the level of adverse effects rate immediately following the policy change (P<0.001; Table 2). Sensitivity analyses including unspecified drug codes with our opioid-related codes yield similar results and inferences: no effect of the policy on opioid overdoses and a significant decrease in the level of opioid-related adverse effects rate post-policy (Supplemental Table 2).

For models stratified by prescription history for chronic, intermittent, and none during the lead-in period, our results (Table 3) show that opioid-naïve patients had a positive adverse effect rate slope in the pre-period (P=.009); adverse effect rates were increasing leading up to the policy intervention. Immediately after the policy change, our results show a decrease in the level of the opioid-related adverse effects rate among those with chronic opioid prescription history (83% decrease, P=.049) and among those with no opioid prescription history (82% decrease, P=.004). Sensitivity analyses including unspecified drug codes with our opioid-related codes yielded similar results and inferences (Supplemental Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this study of patients receiving primary care within an academic medical center, implementation of a statewide opioid prescribing policy was associated with decreased opioid-related adverse effects rate and no change in overdose rate in the first year following the policy change. This study’s unique examination separating opioid overdose and opioid-related adverse effects revealed important differences for these two outcomes, not revealed in previous studies. Our results suggest that the prescribing policy did not significantly change opioid overdose rate in a primary care population. This finding may help assuage concerns among primary care practitioners that limiting prescription opioids will result in more illicit opioid use and overdoses.15 Our results showing decreased adverse effects rate following the policy change are consistent with other studies reporting decreased prescribing following similar policy changes in the Eastern USA.11,12,25,26 A novel finding from the current study is that opioid-naïve primary care patients and those with a history of chronic opioid prescriptions experienced the most dramatic reduction in the rate of opioid-related adverse effects after the policy.

We view these findings in relation to other efforts ongoing in Vermont and other states to improve treatment for opioid use disorder. Starting in 2013, the “Hub and Spoke” model in which high-intensity treatment in “hubs” transitioning to maintenance treatment in “spokes” was being implemented in Vermont to expand medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD).27 January 2016 was the beginning of the decrease in the longstanding waitlist for treatment in hubs, down to near zero by July 2018.28 This translates to more people accessing MOUD during our study period, specifically buprenorphine, a partial agonist, which does not result in sedation and slow respiration (two common adverse effects) the way full agonists, like prescription opioids, do. Therefore, improving access to partial-agonists may have contributed to some of the decrease in hospital utilization for adverse effects over time; however, our effect was an immediate change in level after the prescription policy went into effect, so less access to prescription opioids was the likely driver lowering adverse effects rate. In addition, mandating the use of the PDMP as part of the policy likely helped decrease patient access to excess prescription opioids beyond those prescribed safely by their PCP. One final contextual factor to consider was that local harm reduction interventions were in effect prior to the policy, including naloxone distributed at the state’s largest mental health treatment center (2013), carried by police (January 2016), and available at pharmacies statewide (September 2016).29

Opioid-naïve patients and those with chronic opioid prescription history experienced the largest decreases in our adverse effects outcome, though we did not find that opioid prescription history modified the effect of the policy on our opioid overdose outcome. One other study looked specifically at opioid-naïve patients in Massachusetts, and they found no change in opioid overdoses over a 4-year period, but this was prior to their opioid prescribing policies.30 Our results of decreased adverse effects rate among opioid-naïve patients add to earlier studies showing that opioid-naïve patients were at the greatest risk of postoperative chronic opioid use31 and that larger dose and longer duration of prescriptions was associated with increased opioid misuse among opioid-naïve patients.32 Some of the opioid-naïve patients with opioid-related adverse effects in our study did not have a prescription in the EMR system during any time in the study period and therefore were likely receiving opioids from outside the medical center, not overseen by a PCP. Patients on prescription opioids overseen by their PCP may be better able to take the medicine as prescribed and to communicate about any effects they are experiencing before those effects require additional medical attention.33 Patients with chronic opioid prescription history also experienced a decreased adverse effects rate following the policy change. The magnitude of the decrease was like that seen among opioid-naïve patients, and significant, despite the smaller sample size. For acute pain, Vermont’s policy restricts dosing to <7 days. While there were no dosing restrictions for chronic pain, there were requirements for extensive documentation, in-person meeting, re-evaluation after 90 days, and naloxone co-prescription for higher dosing. These new requirements may have helped PCPs better manage their patients requiring chronic opioid prescriptions, thus decreasing adverse effects from overprescribing. In 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published “CDC Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain”.33 More recently, the Health Resources and Services Administration invested in primary care’s integration of behavioral health services and enhanced access to primary care-based substance use disorder services such as MOUD.34 These added resources may have helped PCPs transition patients with chronic opioid prescriptions with risky behaviors to treatment for opioid use disorder and reduced adverse effects and overdose by shifting prescribing to more supervised settings.

The lack of change in overdose rate in this study is reassuring. It may reflect a balance between patients seeking illicit opioids and overdosing and patients avoiding an overdose from large doses received by prescription. In a separate study by our research team testing these models on population-level all-payer claims data,35 we observed a concerning and immediate increase in opioid overdose rate following the prescribing policy. One consideration for why we did not observe a similar immediate increase in our primary care patients is that our medical center primary care network is well connected to the hub and spoke model in the state, and these connections may have also helped our primary care patients mitigate this risk for overdose. A Canadian study also showed no change in opioid-related hospitalizations after reduced prescribing and speculated it may have been due to patients with chronic opioid prescriptions receiving increasing doses over the same time period.36 The very small number of patients with chronic opioid prescriptions overdosing during the study period limits our ability to investigate the impact the policy may have had on them and may indicate that PCPs are managing patients with chronic opioid prescriptions well. A recent study of six health care systems indicated that treatment for opioid use disorder within primary care is still limited,37 and integrating this care will improve the management of opioid use disorder.

These analyses have limitations. First, nearly 25% of our sample were >65 years (which is consistent with adult, rural, primary care populations), and this may have limited our ability to assess opioid overdoses, occurring primarily among those 25–34 years (15% of the sample). Second, ED diagnoses often used “unspecified narcotic” codes to indicate opioids because of lack of laboratory verification, thus limiting our ability to investigate the type of opioid. Third, while our data included all opioid-related deaths occurring in and out of the hospital, it did not include opioid-related community events where the patient survived. Fourth, we did not analyze the prescriptions of patients pre- and post-policy, and future studies could look at the impact of new prescriptions among the opioid-naïve population specifically. Finally, data were from a single medical center in a small, rural, northeastern state, though it represents the largest medical center in the state with eleven primary care practice locations.

Conclusion

Vermont’s policy limiting prescription opioids reduced the rate of opioid-related adverse effects and did not change opioid overdose rate among primary care patients. Adverse effects rate reductions were most pronounced in opioid-naïve patients and those with chronic opioid prescriptions. Limiting the quantity and duration of opioid prescriptions had positive results for primary care patients. We recommend continued monitoring of outcomes across states to determine whether these findings are consistent in other settings and populations, and over time. Additionally, prescribing policy changes are expected to have benefits on reducing new opioid use in the population.

References

Seth P, Rudd RA, Noonan RK, Haegerich TM. Quantifying the Epidemic of Prescription Opioid Overdose Deaths. Am J Public Health 2018;108(4):500-2. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304265

Rosenblum A, Marsch LA, Joseph H, Portenoy RK. Opioids and the treatment of chronic pain: controversies, current status, and future directions. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2008;16(5):405-16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013628

Compton WM, Volkow ND. Major increases in opioid analgesic abuse in the United States: concerns and strategies. Drug Alcohol Depend 2006;81(2):103-7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.009

Institute of Medicine Committee on Advancing Pain Research Care and Education. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/13172/relieving-pain-in-america-a-blueprint-for-transforming-prevention-care.

Mularski RA, White-Chu F, Overbay D, Miller L, Asch SM, Ganzini L. Measuring pain as the 5th vital sign does not improve quality of pain management. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21(6):607-12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00415.x

Tompkins DA, Hobelmann JG, Compton P. Providing chronic pain management in the "Fifth Vital Sign" Era: Historical and treatment perspectives on a modern-day medical dilemma. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;173:11-21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.12.002

Merboth MK, Barnason S. Managing pain: the fifth vital sign. Nursing Clinics of North America Journal 2000;35(2):375-83.

Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in Opioid Analgesic–Prescribing Rates by Specialty, U.S., 2007–2012. Am J Prev Med 2015;49(3):409-13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.020

Pitt AL, Humphreys K, Brandeau ML. Modeling Health Benefits and Harms of Public Policy Responses to the US Opioid Epidemic. Am J Public Health 2018;108(10):1394-400. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304590

Vermont Department of Health. Rule Governing the Prescribing of Opioids for Pain. In: Vermont Department of Health. 2017. Available from: https://www.healthvermont.gov/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/REG_opioids-prescribing-for-pain.pdf.

MacLean CD, Fujii M, Ahern TP, et al. Impact of Policy Interventions on Postoperative Opioid Prescribing. Pain Med 2019;20(6):1212-8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pny215

Dave CV, Patorno E, Franklin JM, et al. Impact of State Laws Restricting Opioid Duration on Characteristics of New Opioid Prescriptions. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34(11):2339-41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05150-z

Fujii MH, Malhotra AK, Jones E, Ahern TP, Fabricant LJ, Colovos C. Postoperative Opioid Prescription and Usage Patterns: Impact of Public Awareness and State Mandated-Prescription Policy Implementation. J Am Coll Surg 2019;229(4, Supplement 1):S109. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.08.245

Rubin R. Limits on Opioid Prescribing Leave Patients With Chronic Pain Vulnerable. JAMA. 2019;321(21):2059-62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.5188

O’Donnell JK, Halpin J, Mattson CL, Goldberger BA, Gladden RM. Deaths Involving Fentanyl, Fentanyl Analogs, and U-47700 - 10 States, July-December 2016. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66(43):1197-202. doi:https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6643e1

Hooten WM, St Sauver JL, McGree ME, Jacobson DJ, Warner DO. Incidence and Risk Factors for Progression From Short-term to Episodic or Long-term Opioid Prescribing: A Population-Based Study. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90(7):850-6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.04.012

Raebel MA, Newcomer SR, Reifler LM, et al. Chronic Use of Opioid Medications Before and After Bariatric Surgery. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1369-76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.278344

Epic Systems Corporation. EpicCare. Verona, WI 2020. Available from: https://www.epic.com/.

Boudreau D, Von Korff M, Rutter CM, et al. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009;18(12):1166-75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.1833

Von Korff M, Saunders K, Ray GT, et al. Defacto long-term opioid therapy for non-cancer pain. Clin J Pain 2008;24(6):521.

Imam MZ, Kuo A, Ghassabian S, Smith MT. Progress in understanding mechanisms of opioid-induced gastrointestinal adverse effects and respiratory depression. Neuropharmacology. 2018;131:238-55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.12.032

Kiyatkin EA. Respiratory depression and brain hypoxia induced by opioid drugs: Morphine, oxycodone, heroin, and fentanyl. Neuropharmacology. 2019;151:219-26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.02.008

R Foundation for Statistical Computing. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Version 3.5.1 ed. Vienna, Austria 2014. Software. Available from: http://www.R-project.org.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software. Release 15 ed. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2017. Software.

Lowenstein M, Hossain E, Yang W, et al. Impact of a State Opioid Prescribing Limit and Electronic Medical Record Alert on Opioid Prescriptions: a Difference-in-Differences Analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35(3):662-71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05302-1

Krebs EE. Evaluating Consequences of Opioid Prescribing Policies. J Gen Intern Med 2020:1-2. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05600-8

Brooklyn J, Sigmon S. Vermont Hub-and-Spoke Model of Care for Opioid Use Disorder: Development, Implementation, and Impact. J Addict Med 2017;11(4):286-92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000310

Vermont Department of Health. Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) Treatment Census and Waitlist as of November 2019. January 2020. Available from: https://www.healthvermont.gov/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/ADAP_OpioidUseDisorderTreatmentCensusandWaitList.pdf.

O’Neill K. Evolution of an Epidemic: A Timeline of the Vermont Opioid Crisis. Saven Days VT. 2019. Available from: https://www.sevendaysvt.com/vermont/evolution-of-an-epidemic-a-timeline-of-the-vermont-opioid-crisis/Content?oid=25605835.

Burke LG, Zhou X, Boyle KL, et al. Trends in opioid use disorder and overdose among opioid-naive individuals receiving an opioid prescription in Massachusetts from 2011 to 2014. Addiction. 2020;115(3):493-504. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14867

Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Chronic Opioid Use Among Opioid-Naive Patients in the Postoperative Period. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176(9):1286-93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3298

Brat GA, Agniel D, Beam A, et al. Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naive patients and association with overdose and misuse: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018;360:j5790. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j5790

Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-45.

Steinberg J. Special Edition: The Opioid Epidemic. In: Primary Health Care Digest. Health Resources and Services Administration,. 2018. https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USHHSHRSA/bulletins/1e8d493.

Harder VS, Varni SE, Murray KA, et al. Prescription Opioid Policies and Associations with Opioid Overdose and Related Adverse Effects. International Journal of Drug Policy. Under Revised Review 2021.

Spooner L, Fernandes K, Martins D, et al. High-Dose Opioid Prescribing and Opioid-Related Hospitalization: A Population-Based Study. PLoS One 2016;11(12):e0167479. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167479

Lapham G, Boudreau DM, Johnson EA, et al. Prevalence and treatment of opioid use disorders among primary care patients in six health systems. Drug Alcohol Depend 2020;207:107732. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107732

Funding

This study is financially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences for the Northern New England Clinical and Translational Research network as a supplement (grant number U54 GM115516-S1). VSH and ACV were also supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) center of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS; grant number UD9 RH33633) from the US Department of Health and Human Services. ACV was also supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant number P20 GM103644).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Brooklyn receives personal fees from his work as Medical Director of OpiSafe. There are no other conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, HRSA, HHS, or the US Government.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations: We presented preliminary results at the Society for General Internal Medicine, May 2019, and at the American Psychopathological Association, March 2020.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 19 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harder, V.S., Plante, T.B., Koh, I. et al. Influence of Opioid Prescription Policy on Overdoses and Related Adverse Effects in a Primary Care Population. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 2013–2020 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06831-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06831-4