Abstract

Background

Hospitals are increasingly screening patients for social risk factors to help improve patient and population health. Intelligence gained from such screening can be used to inform social need interventions, the development of hospital-community collaborations, and community investment decisions.

Objective

We evaluated the frequency of admitted patients’ social risk factors and examined whether these factors differed between hospitals within a health system. A central goal was to determine if community-level social need interventions can be similar across hospitals.

Design and Participants

We described the development, implementation, and results from Northwell Health’s social risk factor screening module. The statistical sample included patients admitted to 12 New York City/Long Island hospitals (except for maternity/pediatrics) who were clinically screened for social risk factors at admission from June 25, 2019, to January 24, 2020.

Main Measures

We calculated frequencies of patients’ social needs across all hospitals and for each hospital. We used chi-square and Friedman tests to evaluate whether the hospital-level frequency and rank order of social risk factors differed across hospitals.

Results

Patients who screened positive for any social need (n = 5196; 6.6% of unique patients) had, on average, 2.3 of 13 evaluated social risk factors. Among these patients, the most documented social risk factor was challenges paying bills (29.4%). The frequency of 12 of the 13 social risk factors statistically differed across hospitals. Furthermore, a statistically significant variance in rank orders between the hospitals was identified (Friedman test statistic 30.8 > 19.6: χ2 critical, p = 0.05). However, the hospitals’ social need rank orders within their respective New York City/Long Island regions were similar in two of the three regions.

Conclusions

Hospital patients’ social needs differed between hospitals within a metropolitan area. Patients at different hospitals have different needs. Local considerations are essential in formulating social need interventions and in developing hospital-community partnerships to address these needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

The environments in which people live, work, and play are major determinants of their life expectancy and overall health.1, 2 Indeed, 40–90% of health outcomes are related to economic, social, and behavioral elements,3 and social risk factors are associated with adverse health conditions,4 emergency department visits,5 hospitalizations,5 and hospital readmissions.6 Acknowledging the interaction between the environments in which people reside and their health, a number of professional medical associations recommend screening patients for social determinants of health.7,8,9,10 Through clinically screening patients for social risk factors, providers may gain valuable information when diagnosing, treating, and managing patient care.11,12,13 In addition, the information gained from clinically screening patients for social risk factors can be used to inform population health management interventions as well as community investment decisions.14, 15 Accordingly, many medical practices,16 community clinics,17 and hospitals16 are now clinically screening patients for social risk factors.

The majority of the literature regarding clinically screening patients for social risk factors has focused on the screening process.18 Challenges and barriers to social risk factor screening and treatment identified in this literature include limited resources for social risk factor interventions,16, 19 practitioner concerns regarding the time/resources required to address social risk factors,20 gaps in clinician/staff social risk factor knowledge,9, 12, 20 identifying partnerships/interventions to address social risk factors,14 and deciding which patients to screen.21 Each of these barriers merits consideration. However, health organizations need to know the social needs of their patients and communities and whether these needs are similar within geographic areas before formulating an intervention, developing clinical/staff education, identifying a treatment population, or determining how to allocate community investment dollars.

Beyond studies documenting social risk factors among patients clinically screened in community health centers,17, 22 little is known about which social risk factors are most frequently documented in hospital settings.17 Indeed, Fraze et al. found that just 42.7% of hospitals screened for any social risk factor beyond interpersonal violence.16 It is also unknown as to whether social risk factors differ across hospitals within the same metropolitan area. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the frequency with which patients clinically screen for social risk factors across 12 hospitals and to examine whether patients’ social risk factor needs differ across these hospitals.

Results from this study will provide insights into the social needs of admitted hospital patients, which may differ from those of the general community.23, 24 Furthermore, by evaluating whether patient social risk factors differ across hospitals within the same area, results from this study will provide stakeholders with intelligence to use in structuring social need interventions and allocating community investment resources. For example, the results will provide insight into whether the same interventions can be used at all hospitals within a community (no difference in social risk factors) or whether interventions within a community should be tailored to the unique needs of each hospital’s population (social risk factors differ between hospitals). Additionally, reporting the social needs of hospital patients also provides a point of comparison for other hospitals to use when evaluating their own social risk factor screening programs and can be beneficial to stakeholders as they consider developing payment mechanisms for addressing social risk factors within a clinical setting.25

METHODS

The study occurred at 12 Northwell Health hospitals in the New York City/Long Island (NYC-LI) metropolitan area. Northwell Health (Northwell), a health care system consisting of 23 hospitals and other health services organizations, serves 2 million patients in the New York City, Long Island, and Westchester areas. Northwell’s Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Screening Tool Development

An interdisciplinary committee consisting of physicians, nurses, dietitians, social services, case management, administration, and members of academic affairs and hospital/system administration developed Northwell’s social risk factor screening module. The committee considered best practices,26 validated survey questions,27,28,29 and the communities in which Northwell serves29 while developing questions (Table 1, online Appendix Tables 1 and 2) for the screening module. The system’s nursing admission documentation already included contextual patient information that might influence patients’ clinical care. Thus, to avoid redundancy,18 the committee did not create new questions for the screening module if questions, relating to module’s social risk factors, already existed in the system’s nursing admission documentation. The screening module’s delivery mechanism was based upon formative research and entailed incorporating the screen into Northwell’s existing electronic medical record (EMR). Nurses are expected to administer the 13-subject multiple question screen (online Appendix Tables 1 and 2) to all adult patients (except maternity patients) during admission or within 24 h of admission. Across all initial questions, the expected response is yes/no. Patients who answer yes to a question are considered to have the evaluated social risk factor and are asked follow-up free text questions. Patients who screen positive for a social risk factor, except for health literacy, receive an automatic social work consult. Patients who screen positive for a health literacy need receive an automatic case management consult. Patients can thus receive two social need-based consults during their stays (i.e., social work and case management). The verbal responses that patients or their family members provide to the questions are documented directly into the EMR. Nurses use translation services for patients where such is needed.

The social risk factor screening module and delivery mechanism addressed many challenges identified in the literature.20, 30 For instance, physicians were involved throughout the development of the social risk factor screen and delivery mechanism, accounting for the need to involve clinicians in the process.30 To standardize the screening process, and to address physicians’ time constraint concerns, the screen was incorporated into Northwell’s existing EMR system and is administered at admission.20 Physicians’ time constraint concerns were also addressed by developing a clinical team-based care approach where case management and social work have an active role in attending to patients’ social needs.

Process improvement tools such as rapid prototyping and Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles are used to evaluate and adjust the screening, intervention, and referral process. For instance, the screening module and delivery mechanism were test piloted at one hospital. Residents and members of Graduate Medical Education managed the 20-week test pilot which consisted of screening 129 admitted patients. The test pilot resulted in several process adjustments. For instance, screening patients within 24 h of admission as the optimal screening time, incorporating the screen into the nursing admission profile, and the creation of an automated referral mechanism for positive screens to social work/case management were some of the recommendations that were generated through the pilot. The committee approved the adjusted, finalized social risk factor questions and screening mechanism. The committee subsequently developed in-service and education sessions on social determinants of health, the screening module, and the process for addressing patients’ identified social risk factors; all providers and administrative staff with patient interaction on social risk factors are expected to complete these educational sessions. The interactive provider led training modules lasted 1 h or 1.5 h (case management and social work only).

After completing the pilot, Northwell implemented the screening module into the EMR-based nursing admission document at 11 other hospitals that have the same electronic medical record system.

Data and Study Population

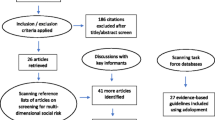

The study population consisted of all patients admitted to one of the 12 hospitals who had at least one social risk factor documented, from June 25, 2019, to January 24, 2020, except for patients admitted to maternity/pediatrics. Patients in the emergency department or under observation are not considered admitted (would not have inpatient admission documents) and thus were excluded from the study population. Figure 1 illustrates how the study sample of 5196 patients with social risk factor needs was generated from the sample population. Out of patients with social risk factor screens (n = 79,003), 5196 (6.6%) had at least one social risk factor documented. Patients’ clinical, demographic, and social risk factor information, as well as the name of the hospital where they were treated, were extracted from their EMRs. Binary variables were created to denote whether patients indicated having or not having each social risk factor (Table 1). In addition, a variable indicating patients’ total number of social risk factors was calculated.

Study Variables

Patients’ clinical characteristics consisted of their treatment episode LACE index and clinical diagnoses. LACE is a prediction measure for post-discharge early deaths and unplanned readmissions.31 Patients’ clinical diagnoses were based upon their principal, admission, final, and secondary diagnosis, as well as their past medical histories, at the admission where the social risk factor screen was administered. The diagnoses were classified into 19 International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition collapsed categories.32 Patients’ demographic information included gender (female, male), age (years), race (African American/Black, Asian, other race, and White), preferred language as captured by nursing at the time of admission (English, Spanish, and other), religion (Baptist, Catholic, Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and other), ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic, and other), and health insurance status (Medicaid, Medicare, and other/commercial). Twelve binary variables were created to indicate patients’ treatment hospitals. Hospitals were placed into one of three NYC-LI regions for regional comparisons (Table 2). Placement within regions were based upon whether the hospitals operated within New York City or one of two Long Island counties. Due to the population density of the NYC-LI area, hospitals may operate within close proximity of one another.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for patients’ social risk factors and other variables were estimated at the patient and hospital levels. Whether the hospital-level frequency of each social risk factor statistically differed across the hospitals was examined with chi-square tests. We ranked the frequency of patient social risk factors, at the hospital level, in the order of highest to lowest. Variance in ranks across the hospitals (e.g., did the ranks differ) was evaluated with the Friedman test33 at three levels: variance between the 12 hospitals, variance between the three NYC-LI regions (A, B, C), and variance between the hospitals within their respective NYC-LI regions. Stata 16 was the primary statistical software used to complete the analyses.34

RESULTS

Patient demographic and clinical information at the hospital level (Table 3) illustrates the diverse patient populations seen across the study hospitals, which also varied greatly (Table 4). For instance, as illustrated in Table 3, the percentage of patients who identified as a race other than White had a range of 60.6% (22.4%, 83.0%) and a median of 57.1% across the hospitals. For the percentage of patients with Medicaid, the range was 27.1% (16.3%, 43.3%) with a median of 33.1%.

Patients with social needs had, on average, 2.1 different social risk factors; among these patients, challenges paying bills was the most documented social risk factor (29.4%), followed by needed assistance with dental/health insurance (24.5%) as well as needed assistance with other public benefits (24.4%). The dominant individual level social risk factors (Table 1) were also the primary social risk factors at the hospital level (Table 4). However, with the exception of challenges paying bills, the frequency of social risk factors, among hospital patients with social needs, statistically differed across the hospitals for all social risk factors (Table 4). For example, the percentage of hospital patients, with social needs, who needed assistance with dental/health insurance statistically differed (p = 0.002) across the hospitals with a minimum of 12.7% of hospital patients and a maximum of 31.8% of hospital patients.

Even though the frequency of all but one of the social risk factors differed across the hospitals, the rank order of the social risk factors could still be the same across the hospitals. For example, the percentage of a social risk factor could be 19% in one hospital and 51% in another hospital and, despite the difference in these numbers, still be the top-ranked social risk factor in each hospital. Thus, the frequency of each social risk factor, among a hospital’s patients with social needs, was ranked from most to least frequent in Table 5. Friedman test results indicated a statistically significant variance in ranks between the 12 hospitals (Friedman test statistic (FTS) 30.8 > 19.7: χ2 critical (χ2), p = 0.05). A statistically significant variance in ranks (FTS 7.5 > 6.0: χ2, p = 0.05) was also present across the three NYC-LI regions (i.e., after collapsing hospital data into regional frequencies, the ranks of the three regions differed). However, within each NYC-LI region, the ranks only significantly varied among hospitals within region B (FTS 11.5 > 9.5: χ2, p = 0.05). In regions A and C, the FTS values (5.8; 0.7) were less than the 5% χ2 critical values (5.8; 3.8).

DISCUSSION

The move towards value-based payment and the renewed interest in the relationship between social determinants of health and health outcomes2, 35 has resulted in many health care organizations clinically screening patients for social risk factors. Despite the number of hospitals screening for social risk factors,16 little is known about patients’ social risk factor needs within hospitals and whether these needs differ across hospitals; information that is needed to develop interventions to address patients’ social needs. The results here provide novel information regarding the social needs of hospital patients. The study also illustrates that, overall, patients’ social risk factors statistically differed across the 12 examined hospitals, located within the same metropolitan area, in terms of both frequency and rank order.

The novelty of reporting the distribution of social risk factors across multiple hospitals where the data was generated through EMR-based clinical screening prevents direct comparisons with other studies. However, the results here are similar to findings from a study examining patients clinically screened in community health centers17, 22 as well as a population of managed care patients surveyed about their social risk factors.6 Challenges in paying bills and transportation were both high ranking social risk factors among the managed care patients who were surveyed after at least one acute care admission.6 While among the community health center patients, financial resource strain was a frequently identified social risk factor.17, 22

The information gained from clinically screening patients for social risk factors can be used to address patient needs. For instance, 11.7% of patients who screened positive for social risk factors indicated skipping medication as a social risk factor; a challenge that could exacerbate patients’ disease states, especially older adults with chronic conditions.36 With the real-time knowledge, gained from the screen, that a patient is not able to afford medication, providers could adjust treatment plans or engage hospital staff to address the medication challenges in real-time.13, 37 It is this real-time, actionable intelligence that distinguishes EMR-based social screening information from that gained from the US Census or other sources. Despite the possible benefits of incorporating social risk factors into real-time patient care, the complexity of doing such remains challenging. For instance, Friedman et al. found that the efficacy of screening and addressing social risk factors to be highly dependent upon the availability of patient navigation, effective workflows, and available resources to address patients’ social needs.38 Additionally, a monitoring system is needed to continuously evaluate whether the screening process results in added-value. Finally, future work should evaluate workflows/processes to help ensure that systems are in place to connect patients with needed resources.

When standardized and aggregated, patient social risk factor data obtained through EMR-based clinical screening can also be used to formulate community interventions, community investment decisions,39, 40and to develop community partners to help address patients’ social needs. For example, challenges paying bills was a frequently noted social risk factor among patients in many of the 12 hospitals. From this finding, hospital systems could identify community partners and then collectively develop a standard financial counseling intervention to use across the community.13, 41 However, results from this study illustrate that standard community-level social risk factor interventions should be flexible so that local hospital-level stakeholders can further adjust the interventions to account for even more local considerations. Indeed, the hospitals in this study are all located within the same metropolitan area. Nevertheless, each hospital has a patient population with its own distinct social risk factor needs. These differences between hospitals suggest that developing community-level interventions and partnerships will likely be most effective if constructed, implemented, and managed on a local level.

Limitations

Understanding why hospitals may differ on social risk factors and the effectiveness of social risk factor interventions are related areas of research that merit study. However, first, whether differences in social risk factors between hospitals existed needed to be examined, such differences were estimated to be present in this study. These differences could merely be numerically and not clinically significant. However, the numerical differences in social risk factor needs between hospitals remain important as this data provides information for stakeholders to use when determining how to allocate hospitals’ community investment resources. Additionally, it should be noted that the frequencies reported here are not prevalence rates among all hospital patients, but the prevalence of social risk factors among admitted patients with social risk factors. In this manner, the prevalence of these factors across all patients is lower than that reported here. How the results found here compare with social risk factor frequencies in other hospitals and health systems should be examined.

Education and in-service training was provided to nursing staff across all hospitals on administering the EHR-based social risk factor screen. However, variation in the collection process may have differed within and across hospitals which could influence the results and is a study limitation. Evaluating possible differences in the screening process including the time taken to administer the screen is an area for future process improvement projects.

CONCLUSION

The clinically identified social needs of hospital patients are not well known. The clinical screening process and data illustrated here demonstrate the feasibility of identifying, collecting, and aggregating patient social needs at the hospital level to use in treatment plans and intervention development. However, it was also found that social needs differed across hospitals within the same metropolitan area. This result suggests that the same intervention might not work across all hospitals. Accordingly, interventions and community partnerships may be best developed on a local level or, at least, should account for local considerations.

The hospital-based, social risk factor screening module and delivery mechanism evaluated here was one health system’s initial step in addressing the social needs of its patients and communities. How the screening module, delivery mechanism, and results illustrated in this study compare to other geographies and health care systems merits evaluation.

References

Wilkinson R, Weltgesundheits organisation, eds. The Solid Facts: Social Determinants of Health. 2nd ed. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2003. .

Healthy People 2020 |. https://www.healthypeople.gov/. Accessed March 24, 2020.

Fraze T, Lewis VA, Rodriguez HP, Fisher ES. Housing, Transportation, And Food: How ACOs Seek To Improve Population Health By Addressing Nonmedical Needs Of Patients. Health Aff. 2016; 35(11):2109-2115. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0727

Pantell MS, Prather AA, Downing JM, Gordon NP, Adler NE. Association of Social and Behavioral Risk Factors With Earlier Onset of Adult Hypertension and Diabetes. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e193933-e193933. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3933

Mosen DM, Banegas MP, Benuzillo JG, Hu WR, Brooks NB, Ertz-Berger BL. Association Between Social and Economic Needs With Future Healthcare Utilization. Am J Prev Med. 2019.

Emechebe N, Lyons PT, Amoda O, Pruitt Z. Passive social health surveillance and inpatient readmissions. Am J Manag Care. 2019; 25(8):388-95.

Social Determinants of Health Policy. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/social-determinants.html. Accessed March 7, 2020.

Addressing Social Determinants to Improve Care and Promote Health Equity | Ann Intern Med | American College of Physicians. https://annals.org/aim/article-abstract/2678505. Accessed March 7, 2020.

Chan WV, Pearson TA, Bennett GC, et al. ACC/AHA Special Report: Clinical Practice Guideline Implementation Strategies: A Summary of Systematic Reviews by the NHLBI Implementation Science Work Group: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(8):1076-1092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.004

Professional Medical Association Policy Statements on Social Health Assessments and Interventions. Perm J. 2018. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/18-092

Behforouz HL, Drain PK, Rhatigan JJ. Rethinking the social history. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(14):1277-9.

Adler NE, Stead WW. Patients in Context — EHR Capture of Social and Behavioral Determinants of Health. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):698-701. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1413945

Bibbins-Domingo K. Integrating social care into the delivery of health care. Jama. 2019;322(18):1763-4.

Gottlieb L, Fichtenberg C, Alderwick H, Adler N. Social Determinants of Health: What’s a Healthcare System to Do? J Healthc Manag. 2019;64(4):243–257. https://doi.org/10.1097/JHM-D-18-00160

Gottlieb LM, Quiñones-Rivera A, Manchanda R, Wing H, Ackerman S. States’ influences on Medicaid investments to address patients’ social needs. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(1), 31-37.

Fraze TK, Brewster AL, Lewis VA, Beidler LB, Murray GF, Colla CH. Prevalence of screening for food insecurity, housing instability, utility needs, transportation needs, and interpersonal violence by US physician practices and hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e1911514

Cottrell EK, Dambrun K, Cowburn S, Mossman N, Bunce AE, Marino M, Krancari M, Gold R. Variation in electronic health record documentation of social determinants of health across a national network of community health centers. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6):S65-73.

LaForge K, Gold R, Cottrell E, Bunce AE, Proser M, Hollombe C, Dambrun K, Cohen DJ, Clark KD. How 6 organizations developed tools and processes for social determinants of health screening in primary care: an overview. J Ambul Care Manage. 2018;41(1):2.

Alderwick H, Hood-Ronick CM, Gottlieb LM. Medicaid investments to address social needs in Oregon and California. Health Aff. 2019;38(5):774-81.

Schickedanz A, Hamity C, Rogers A, Sharp A, Jackson A. Clinician experiences and attitudes regarding screening for social determinants of health in a large integrated health system. Med Care. 2019;57(suppl 6 2):S197–S201.

Alderwick H, Gottlieb LM. Meanings and misunderstandings: a social determinants of health lexicon for health care systems. The Milbank Quarterly. 2019;97(2).

Gold R, Bunce A, Cowburn S, et al. Adoption of social determinants of health EHR tools by community health centers. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(5):399-407. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2275.

Coffield E, Kausar K, Markowitz W, Dlugacz Y. Predictors of Food Insecurity for Hospitals’ Patients and Communities: Implications for Establishing Effective Population Health Initiatives. Popul Health Manag. 2019:pop.2019.0129. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2019.0129

Gottlieb LM, Francis DE, Beck AF. Uses and misuses of patient- and neighborhood-level social determinants of health data. Perm J. 2018;22:18-078. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/18-078

Gottlieb LM, DeSalvo K, Adler NE. Healthcare Sector Activities to Identify and Intervene on Social Risk: An Introduction to the American Journal of Preventive Medicine Supplement. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6):S1.

Uwemedimo OT, May H. Disparities in utilization of social determinants of health referrals among children in immigrant families. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:207.

National Association of Community Health Centers Inc., Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations, Oregon Primary Care Association. PRAPARE: Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patient Assets, Risks, and Experiences. 2016. www.nachc.org/researchand-data/prapare

Health Leads. Social Needs Screening Toolkit. 2016. https://healthleadsusa.org/resources/the-health-leads-screeningtoolkit

Gundersen C, Engelhard EE, Crumbaugh AS, et al. Brief assessment of food insecurity accurately identifies high-risk U.S. adults. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(8):1367-1371

Davidson KW, McGinn T. Screening for social determinants of health: the known and unknown. Jama. 2019;322(11):1037-8.

van Walraven C, Dhalla IA, Bell C, Etchells E, Stiell IG, Zarnke K, et al. Derivation and validation of an index to predict early death or unplanned readmission after discharge from hospital to the community. CMAJ. 2010;182(6):551–7.

ICD-10 : international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: tenth revision, 2nd ed. World Health Organ. 2010; https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/ICD10Volume2_en_2010.pdf

Freund RJ, Wilson WJ. Statistical Methods [Internet]. Vol. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Academic Press; 2003 [cited 2020 Mar 12]. Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=cookie,ip,url&db=nlebk&AN=195510&site=eds-live

StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2019.

Houlihan J, Leffler S. Assessing and Addressing Social Determinants of Health: A Key Competency for Succeeding in Value-Based Care. Prim Care. 2019;46(4):561-574.

Lee S, Jiang L, Dowdy D, Hong YA, Ory MG. Attitudes, Beliefs, and Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence Among Adults Aged 65 or Older With Chronic Diseases. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:E148. Published 2018 Dec 6. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.180190

Lash DB, Mack A, Jolliff J, Plunkett J, Joson JL. Meds-to-Beds: The impact of a bedside medication delivery program on 30-day readmissions. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2019;2(6):674-680.

Friedman NL, Banegas MP. Toward Addressing Social Determinants of Health: A Health Care System Strategy. Perm J. 2018;22:18-095. Published 2018 Oct 22. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/18-095

Nichols LM, Taylor LA. Social determinants as public goods: a new approach to financing key investments in healthy communities. Health Aff. 2018;37(8):1223-30.

Fichtenberg CM, Alley DE, Mistry KB. Improving social needs intervention research: key questions for advancing the field. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6):S47-54.

Weir RC, Proser M, Jester M, Li V, Hood-Ronick CM, Gurewich D. Collecting Social Determinants of Health Data in the Clinical Setting: Findings from National PRAPARE Implementation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020;31(2):1018-35.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Abraham Saraya, MD, MS, for his expertise in Northwell Health’s clinical information systems and his help in extracting the data used in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 13 kb).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kausar, K., Coffield, E., Zak, S. et al. Clinically Screening Hospital Patients for Social Risk Factors Across Multiple Hospitals: Results and Implications for Intervention Development. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 1359–1366 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06396-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06396-8