Abstract

Background

Implementation of evidence-based practices often requires tailoring implementation strategies to local contextual factors, including available resources, expertise, and cultural norms. Using an exemplar case, we describe how health systems engineering methods can be used to understand system-level variation that must be accounted for prior to broad implementation.

Methods

Within the context of a single-center quality improvement activity, a multi-disciplinary stakeholder team used health systems engineering methods to describe how pre-endoscopy antithrombotic management was executed, and implemented a redesigned process to improve clinical care. The research team then conducted multiple stakeholder focus groups at four different health-care systems to describe and compare current processes for pre-endoscopy antithrombotic medication management. Detailed work flow maps for each health-care system were developed, analyzed, and integrated to develop an overarching current work flow map, identify key process steps, and describe areas of process variation.

Results

Five key process steps were identified across the four health systems: (1) place an endoscopy order, (2) screen for antithrombotic use, (3) coordinate medication management, (4) instruct the patient, and (5) confirm appropriate medication management before procedure. Across health systems, we found a high degree of variation in each step (e.g., who performed, use of technology, systematic vs. ad hoc process). This variation was influenced by two key system-level contextual factors: (1) degree of health system integration and (2) role and training level of available staff. These key steps, areas of variation, and contextual factors were integrated into an assessment tool designed to facilitate tailoring of a future implementation and dissemination strategy.

Conclusions

Tools from health systems engineering can be used to identify key work flow process steps, variations in how those steps are executed, and influential contextual factors. This process and the associated assessment tool may facilitate broader implementation tailoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Implementing evidence-based practices can be quite challenging.1 Frequently, multiple complex and interacting implementation strategies are needed to successfully implement and sustain an evidence-based practice within a large health system.2 However, complex implementation efforts should be tailored to the local context.3, 4 Tailoring on an implementation strategy occurs in response to contextual variation while adaptation refers to necessary changes in evidence-based practice being implemented. A critical first step in tailoring implementation interventions is to thoroughly assess the current process and any contextual factors that influence those processes and outcomes. While there are no best practices in the implementation literature on how to accomplish this assessment, certain tools from Lean may help measure and define current processes and their contextual influences.

Lean is an approach commonly used for health-care quality improvement (QI). Lean QI generally focuses on process efficiencies (e.g., reducing wait times) or reducing clinical errors. At the same time, most Lean QI projects are conducted in a single health-care setting (or context).5 Typically, Lean QI projects do not attempt to generate one-size-fits-all models for broad use in many different settings. Rather, they focus on how a process is currently operating and what opportunities exist to improve the process in a single location or setting. To accomplish this goal, Lean QI projects frequently use work flow process maps as a tool to detail the specific delivery steps within the target system. Process mapping is also an increasingly used tool within implementation projects to detail how an innovation will be integrated. It is less often used to facilitate multi-site implementation, dissemination, and scale out.6 Experienced Lean QI practitioners know that gaining an in-depth understanding of a current work flow process (including key steps and reasons why care is delivered this way) is necessary before trying to implement work flow process change.

A similar process mapping approach could be used to describe the current process and contextual factors for a multi-site implementation project. This is particularly relevant for single-center QI projects that aspire to increase their impact through a broader “scale out” to new health systems.7 Process mapping may help address the inherent need to locally tailor interventions intended for multi-site implementation.

We used work flow process mapping to develop an implementation intervention within a single health-care system and to prepare it for multi-system dissemination. Specifically, we aimed to improve the management of antithrombotic medications before gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopic procedures. Our project focused on areas of contextual variation across key steps in the work process and the health system factors influencing that variation. We also developed a checklist that can be used to rapidly assess the drivers of work process variation for our specific implementation intervention. Our goal was to develop a model that other implementation interventions could follow as they prepare for multi-site implementation or dissemination.

METHODS

Quality Improvement Project Description

Oral antithrombotic medications, including anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin, apixaban) and antiplatelet medications (e.g., clopidogrel), are commonly used medications that can cause life-threatening bleeding or thromboembolic complications (e.g., stroke) if not managed properly. With the introduction of many newer antithrombotic medications over the past 5–10 years, each with their own pharmacokinetic properties, properly managing these medications has become increasingly complex. This is particularly true for the management of antithrombotic medications before invasive medical and surgical procedures, when a determination of if and when to stop the medication prior to surgery requires consideration of a patient’s thromboembolic and stroke risk, the procedural bleeding risk, and the individual medication’s pharmacologic properties. A recent survey of primary care and procedural providers on periprocedural medication management found that a third of these providers expressed discomfort with management decision-making and more than 80% of primary care providers wanted more support from their institution.8

Within the context of a quality improvement initiative, we assembled a team of stakeholders at one US academic medical center in the Spring of 2017. The team was charged with understanding the current process of antithrombotic medication management before and after outpatient, non-emergent (elective) GI endoscopy procedures. This procedure was selected as the focus of quality improvement because it is commonly performed in the outpatient setting, especially among patients who take antithrombotic medications (e.g., for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation or to treat coronary artery disease). Additionally, this procedure can be ordered by both GI specialists and primary care providers. The antithrombotic medications considered by the group were oral anticoagulants (warfarin, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban) along with oral antiplatelet medications (clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor). Institutional guidelines were reviewed and updated to address patient- and procedural-risk assessment elements that influence care protocols (the evidence-based practice being implemented). These guidelines were assembled by a multi-specialty group using national guidelines, published literature, and local practice norms. The team consisted of two physicians (one GI specialist and one cardiovascular specialist), an anticoagulation pharmacist, two GI nurses (one who works in the GI clinic and one who works in the endoscopy unit), a staff lead from the endoscopy scheduling office, two information technology specialists, two patient advocates, a performance improvement coach (with expertise in systems engineering methods), and a research associate. Team members were selected to represent all relevant stakeholders of the evidence-based practice (pre-endoscopy anticoagulation management). Full details of the implementation effort and evaluation metrics are reported separately.9 The main improvement goal of the project was to reduce the frequency of canceled endoscopic procedures.

Work Flow Process Map Development at the Primary Site

Over 5 months, the team met every other week and used a Lean health system engineering approach to develop a detailed work flow process map of the current process for antithrombotic medication management before and after GI endoscopy (Fig. 1). This map was developed from team discussions and direct observations (“going to gemba” in the Lean vernacular) in an iterative manner.

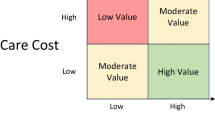

Work flow process map for antithrombotic medication management before GI endoscopy. This figure outlines the five key steps in the work flow process for managing antithrombotic medications before GI endoscopy procedures. Areas of variation between health systems and their associated contextual factors are identified. GI gastrointestinal, EMR electronic medical record, PCP primary care provider, AMS anticoagulation management service.

Secondary Site Focus Groups

Two team members (one physician and one research associate) then conducted focus groups at three other health systems in Michigan, USA. Each of these health systems participates in a quality collaborative focused on anticoagulation care. Similar stakeholders (physicians, nurses, pharmacists, scheduling leads) were invited to participate at each site. These focus groups had two goals: (1) to construct work flow process maps at each of these health systems and (2) to identify contextual factors that may be associated with how the work flow process varied. These focus groups consisted of at least two physicians (one cardiologist or anticoagulation specialist and one gastroenterologist), at least one GI nurse, at least one anticoagulation clinic provider (nurse or pharmacist), and at least one staff member familiar with the scheduling process. Each focus group participant was offered a $30 gift card for their participation. Focus groups lasted approximately 1 h and 30 min. During the focus group, participants were asked to describe their institution’s current process for ordering elective GI endoscopy, identifying which patients are taking antithrombotic medications, and identifying coordination of the management of antithrombotic medications before the endoscopy procedure. Each participant was asked to describe the process related to their role and offer any divergent views about current process steps. We then presented the work flow process map from our index health system and asked the focus group participants to provide any additional clarifications on the work flow process at their institution. Participants were asked to describe what parts of the work flow process work or do not work well at their institution and to comment on potential barriers and facilitators to ideal pre-procedure antithrombotic management. The focus group moderators encouraged broad and diverse sharing of opinions from the focus group participants.

Following each focus group, the team members constructed a work flow map for that site and described the five key process steps for each site. These were constructed through a review of detailed field notes taken by both team members during the focus groups as well as a review of the focus group recordings. The recordings were not transcribed, but instead, the team members conducted analytic memoing. The constructed work flow process maps were then shared individually with the members of the focus group, and their feedback was used to update and correct the work flow process maps for each health system (member checking).10

Identifying Key Work Flow Process Steps and Contextual Variation

After work flow process maps were generated for each of the four health systems, the research team qualitatively compared the maps to identify common themes, which we defined as key work flow process steps. We then iteratively reviewed the individual health system current work flow maps, field notes, and focus group recordings to identify differences in how each health system executed each of the key process steps previously identified. Through a review of known health system characteristics (e.g., size and teaching status) and factors described by the focus group participants (e.g., employee role vs. clinical privileges between physicians and/or physician groups and the health system, number of health systems a physician or physician group works with, EMR availability), we identified contextual factors that influenced the variation in how each health system executed the key process steps.

Using the key steps and contextual variation identified across the four health systems, we developed a self-assessment tool in the form of a checklist. This tool outlined each of the key steps and the potential variation in how each step could be executed (e.g., who performed, use of technology, systematic vs. ad hoc). We also included system-level contextual factors that are associated with the variation seen within each key step during the qualitative data collection and analysis phase detailed above.

This project was approved by the University of Michigan medical institutional review board (HUM00138586).

RESULTS

Across four health-care systems, we interviewed 35 providers and staff members (Table 1, Appendix 1). We generated four distinct work flow process maps, one for each health system. We were able to identify five key work flow process steps that were present in all of the health system processes: (1) placing an order for GI endoscopy, (2) identifying antithrombotic medication use (usually after a GI endoscopy order was placed), (3) coordinating and deciding on management of antithrombotic medication, (4) giving antithrombotic medication management instructions to the patient, and (5) verifying antithrombotic medication management prior to endoscopy procedure (Fig. 1).

Key Work Flow Process Steps

Areas of variation existed within each of the five key work flow process steps (Table 2). For the first step (placing order), some health systems allowed orders to be placed only by GI providers while others allowed non-GI providers (e.g., primary care providers) to place a GI endoscopy order. Similarly, some centers restricted GI endoscopy ordering to providers within their health system, while others allowed non-affiliated providers to order a GI endoscopy procedure.

For the second step (identifying antithrombotic medication use), some health systems relied on clinical staff (e.g., ordering physician, preoperative nurse, GI clinic nurse) while others relied on a non-clinical staff (e.g., scheduler). Some health systems had a systematic process to evaluate all patients for antithrombotic medication use while others did not. Some centers screened for antithrombotic medication use at the time of GI endoscopy order placement through EMR-based tools while others screened at the time of scheduling or during a pre-procedure visit.

For the third step (coordinating and making management decision), some health systems took responsibility for coordinating the management decision-making by assigning it to a nurse or other staff member. Other health systems relied on the patient to contact an appropriate provider for pre-procedure management instructions. Most health systems noted that different providers would make the ultimate decisions about antithrombotic management based on the clinical indication (e.g., cardiologist for patients with a history of coronary stent, vascular surgeon for patients with lower extremity bypass grafts). Some, but not all, health systems relied on the anticoagulation management services to assist with warfarin-treated patients.

For the fourth step (instructing the patient), some health systems relied on whichever provider made the management decision while others communicated via a dedicated staff member (e.g., pre-procedure clinic nurse or anticoagulation management service nurse/pharmacist). Some health systems provided patient instructions face-to-face during a clinic visit, while others routinely relied on phone-based instructions. Some health systems routinely documented the management instructions, while other centers had no standard practice for documentation of pre-procedure medication management instructions.

For the fifth step (pre-procedure management check), some health systems performed a routine check that the antithrombotic medications were managed according to the plan, while other systems did not have a routine pre-procedure check. Of those that did routinely check, some used the GI clinic or endoscopy staff while others used the pre-procedure clinic staff.

Health System Contextual Factors

One key contextual factor that influenced how many of the five process steps were executed was the degree of health system integration, or a health system’s ability to achieve unity of effort across different areas.11 Specifically, health systems with a single or predominant physician group allowed a broader range of providers to place an electronic medical record (EMR) order for the GI endoscopy procedure (first key step). For example, the less integrated health systems in this project did not have mechanisms for non-GI physicians to place a GI endoscopy order. In contrast, the more integrated systems provided an easy mechanism for primary care providers (both within and outside of the health system) to order an endoscopy without the patient ever meeting the GI endoscopy provider in clinic (commonly referred to as “open access”). The more integrated health systems were more likely to have a shared EMR that facilitated identifying antithrombotic medication use (second key step). However, not all of the integrated health systems leveraged that tool to systematically review for antithrombotic medications at the time an endoscopy was ordered. The more integrated health systems were also better able to rely on their shared EMR to communicate between providers when determining how best to manage pre-procedural medications (third key step). However, the less integrated health systems more often relied on a stand-alone clinic (e.g., the preoperative clinic) to manually coordinate medication decision-making and provide patient education about medication management (fourth key step).

At a broader level, each of the integrated health systems employs or contracts with a single group of gastroenterologists who care for patients and perform procedures at that hospital. This eliminates competition between multiple GI provider groups and allows the health system and the GI providers to align their care and business goals.

A second key contextual factor that influenced the second and third key process steps was which staff member or clinician (role) assessed for antithrombotic medication use and how systematic that assessment was. With regard to identifying medication use (second key step), two centers used a non-medical staff person (e.g., GI scheduler) and a verbal checklist to identify patients taking antithrombotic medications. One center incorporated a checklist into the EMR order that providers must fill out at the time a GI endoscopy procedure is ordered. The fourth center had a nurse in the pre-procedure clinic assess for any antithrombotic medications. This staff member’s training also impacted how they were able to coordinate medication management (third key step). At two centers, the non-medical staff member did not routinely take responsibility for contacting a patient’s various providers for care coordination and decision-making. At one center where a pre-procedure clinic nurse screened for antithrombotic medication use, that same nurse was also able to communicate with the patient’s various providers and coordinate decision-making for pre-procedural medication management. None of the centers used an automated EMR alert, rather they each relied on staff (with variable medical training) to assess current medication use.

We integrated the five key process steps and the two elements of contextual variation to create a self-assessment tool (Table 3). For each key process step, we created a list of ways that specific step could be executed, based on the variation described in the focus groups. We also included elements of contextual variation that influence how care currently proceeds. This tool can be used to assess current work flow processes as well as consider how work flow may be redesigned to optimize pre-procedural care given existing contextual factors.

DISCUSSION

We generated work flow process maps of antithrombotic medication management prior to elective GI endoscopy for each of four health systems. Through review and comparison of those process maps, we identified key process steps, areas of variation within those steps, and health system contextual factors that influence how care is provided. We then developed a self-assessment checklist (Table 2) which can be used by any health system to assess how their contextual factors may influence current pre-procedural medication management. This tool may also be used to tailor a future multi-site implementation and/or dissemination plan aimed at improving antithrombotic medication management before elective GI endoscopy procedures.

Clinical leaders and researchers often aim to implement an evidence-based practice across a range of clinical settings (e.g., different health systems, different clinics or wards within a health system). When multi-site implementation is the intent, or when attempting to scale out a project that was successfully implemented in a more limited capacity, our work suggests that detailing the process can be beneficial during the intervention planning and design phase.12, 13 This approach is particularly useful to guide how an implementation strategy may be tailored to local factors.3 For example, addressing blood pressure management across a range of primary care clinics may help to identify key contextual factors (e.g., location where blood pressure is measured, use of manual vs. automated cuff, time that a patient sits before having blood pressure measured) that will influence how an implementation strategy must be tailored. As suggested by the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project, clinics with similar contextual factors (e.g., all those using manual vs. automated cuffs) may be able to share best practices, identify early adopters and share initial experiences, promote network weaving, etc.14 While the process mapping activity does, in part, address the core function or mechanism of change, it also critically helps to understand form and how change may need local tailoring.15 And variation in care delivery is not bad, as long as the end product is delivery of the evidence-based practice.

As noted above, the distinction between adaptation of an evidence-based practice and tailoring of an implementation strategy has not always been well delineated within the dissemination and implementation literature. In our case, the clinical guidelines on how to manage antithrombotic medications before endoscopy procedures (the evidence-based practice) should be fairly consistent between sites as it draws on the published literature. Only minimal adaptation of the guidelines should be needed for guidance with lower quality evidence. However, the methods by which these patients are identified and the clinical decision-making/communication process (the implementation strategies) may need wider variation in how they are executed based on local context. This need to tailor the implementation intervention process can be facilitated through the explicit use of work flow process mapping at multiple sites, identifying key steps in the care process, and identifying how local context influences the care process. Planning the tailoring process up front may facilitate successful implementation and help to avoid potential pitfalls during multi-site implementation or dissemination.

Encouraging pre-specified implementation intervention tailoring is likely to improve the implementation success.16, 17 As we have done with this project, a select group of pilot sites could be approached for large multi-site implementation efforts. A logical next step would be to administer a survey in which each participating site can identify how they currently provide care based on the five key steps identified in the initial single-site quality improvement effort and pilot site focus groups. This information would allow the investigator to help sites with similar processes or characteristics work together to develop tailored implementation strategies that are similar and increase the likelihood of success. Based on our focus group work, the degree of variation was not wide, increasing the likelihood that multiple sites will share characteristics and similar implementation plans.

This process can also inform pre-intervention modeling, another ERIC-recommended implementation strategy.14, 18 Based on the five key work flow process steps identified, each site can model how a change from their current process to a proposed future process might impact care delivery (e.g., frequency of last minute procedure cancelations) or staff needs. Using our endoscopy project as an example, a site that is currently using a pre-procedure clinic to screen for medication use can estimate the accuracy and reduction in staff resource needs if an EMR alert was designed to identify these important medications at the time an endoscopy procedure is ordered. Similarly, by applying data from other sites, a site that requires a patient to coordinate their own pre-procedure medication instructions can model how many resources would be needed to employ a GI clinic nurse or anticoagulation clinic staff member to own that process based on their current clinical volume.

Finally, this process creates a framework for taking a quality improvement intervention developed at a single site and expanding it into a multi-site, complex implementation intervention. In the case presented here, the key intervention includes an improved process to identify patients taking antithrombotic medications before GI endoscopy procedures, a robust process for contacting appropriate providers and obtaining evidence-based instructions for pre-procedure medication management, and a reliable system for communication with the patient and other health-care providers. Through this implementation intervention development process, a research team can ensure tailoring of the implementation strategy to site-specific contextual factors.

We recognize some limitations in our study. First, this process was developed from a single quality improvement project and has not been thoroughly investigated in other projects to ensure external generalizability. Second, while we spent several months detailing the current state at our index facility, we were unable to perform a similarly detailed investigation of their current state processes. However, we were able to identify the details of each key step during a 90–120-min focus group including all of the key stakeholders. In many ways, this process could be replicated for other projects where sufficient resources for in-depth process mapping at multiple sites are not available. Finally, we conducted this process in only four total health-care facilities, each of whom was participating on an anticoagulation quality improvement collaborative. It is possible that other variants of antithrombotic medication management before GI endoscopy exist. However, even with the limitation of four sites, we were able to demonstrate the feasibility of the process.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we demonstrated that the health systems engineering tools used to detail key care process steps can be used to develop a complex implementation intervention with special attention to contextual tailoring. This process also facilitates the collection of key data necessary for implementation modeling. This tool may help larger organizations implement evidence-based practices across diverse clinics or settings with a goal of improving clinical care while anticipating contextual barriers to implementation.

Data Availability

The datasets can be requested through correspondence with the corresponding author and are available upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- EMR:

-

electronic medical record

- ERIC:

-

Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change

- GI:

-

gastrointestinal

- IT:

-

information technology

- PCP:

-

primary care provider

References

Rubenstein LV. Finding Joy in the Practice of Implementation Science: What Can We Learn from a Negative Study? J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(1):9-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4715-0

Skolarus TA, Sales AE. Implementation issues: towards a systematic and stepwise approach. In: Richards DA, Hallberg I, editors. Complex interventions in health: an overview of methods. Abingdon; New York: Routledge; 2015. p. 265-72.

Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, Aarons GA, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, et al. Methods to Improve the Selection and Tailoring of Implementation Strategies. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2017;44(2):177-94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-015-9475-6

Kovacs E, Strobl R, Phillips A, Stephan AJ, Muller M, Gensichen J, et al. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Effectiveness of Implementation Strategies for Non-communicable Disease Guidelines in Primary Health Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(7):1142-54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4435-5

Graban M. Lean hospitals: improving quality, patient safety, and employee engagement. 2nd ed. New York: Productivity Press/Taylor & Francis; 2012.

Standiford T, Conte ML, Billi JE, Sales A, Barnes GD. Integrating Lean Thinking and Implementation Science Determinants Checklists for Quality Improvement: A Scoping Review. Am J Med Qual. 2019:1062860619879746. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860619879746

Aarons GA, Sklar M, Mustanski B, Benbow N, Brown CH. “Scaling-out” evidence-based interventions to new populations or new health care delivery systems. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0640-6

Barnes GD, Kurlander J, Haymart B, Kaatz S, Saini S, Froehlich JB. Bridging Anticoagulation Before Colonoscopy: Results of a Multispecialty Clinician Survey. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(9):1076-7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2016.2409

Barnes GD, Spranger E, Sippola E, Renner E, Ruff A, Sales AE, et al. Assessment of a Best Practice Alert and Referral Process for Preprocedure Antithrombotic Medication Management for Patients Undergoing Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Procedures. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920548. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20548

Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, Campbell C, Walter F. Member Checking: A Tool to Enhance Trustworthiness or Merely a Nod to Validation? Qual Health Res. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316654870

Bazzoli GJ, Shortell SM, Dubbs N, Chan C, Kralovec P. A taxonomy of health networks and systems: bringing order out of chaos. Health Serv Res. 1999;33(6):1683-717.

Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK. Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Ben Charif A, Zomahoun HTV, LeBlanc A, Langlois L, Wolfenden L, Yoong SL, et al. Effective strategies for scaling up evidence-based practices in primary care: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0672-y

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

Kirk MA, Haines ER, Rokoske FS, Powell BJ, Weinberger M, Hanson LC, et al. A case study of a theory-based method for identifying and reporting core functions and forms of evidence-based interventions. Transl Behav Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibz178

Bopp M, Saunders RP, Lattimore D. The tug-of-war: fidelity versus adaptation throughout the health promotion program life cycle. J Prim Prev. 2013;34(3):193-207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-013-0299-y

Chambers DA, Norton WE. The Adaptome: Advancing the Science of Intervention Adaptation. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(4 Suppl 2):S124-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.05.011

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Michelle Moniz, MD, MSc, and Marisa Wetmore for their thoughtful review and comments of an earlier manuscript version.

Funding

This work was funded by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to GDB (K01HL135392). All authors have no other disclosures relevant to this work. The opinions expressed herein are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of NHLBI or any other part of the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Barnes reports grants from NHLBI during the conduct of the study, personal fees from Janssen, grants and personal fees from Pfizer/Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees from Portola, and personal fees from AMAG Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. Other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barnes, G.D., Acosta, J., Kurlander, J.E. et al. Using Health Systems Engineering Approaches to Prepare for Tailoring of Implementation Interventions. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 178–185 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06121-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06121-5