Abstract

Background

A comprehensive picture of how the US population engages in specialty care use is lacking, even though redesign models focused on specialty care are becoming more popular.

Objective

To describe the type of provider, primary care or specialist, most often seen by individuals, to test associations between type of provider most often seen and insurance coverage, and to test associations between the number of generalist and specialist visits and insurance coverage.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of 2013–2016 Medicaid Expenditure Panel Survey. Logistic and negative binomial models were used in multivariate regression modeling.

Participants

Depending on the analysis, the study samples include between 71,402 and 79,518 US residents.

Main Measures

Individuals’ provider type most often seen, primary care visits, and specialist visits were reported.

Key Results

More than half of the sample (55%) predominantly visited primary care providers (or generalists), and 36% predominantly visited specialists. Among individuals primarily visiting generalists, 80% visited only one type of primary care provider, and 24% also visited one or more specialists. Among individuals primarily visiting specialists, 48% visited only one type of specialist, and 47% did not visit any generalists in the year. Among Medicare enrollees, 50% predominantly visited specialists, and 40% predominantly visited generalists. Medicare enrollment was associated with greater odds of predominantly visiting specialists (p < 0.05), and Medicare-Medicaid enrollment and having no insurance were associated with lower odds of predominantly visiting specialists (p < 0.05). Medicare enrollment was associated with 13% more generalist visits and 35% more specialist visits, and Medicare-Medicaid enrollment was associated with 38% more generalist visits and 15% more specialist visits (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Given the overall frequency of specialty care use and the reliance on multiple specialists in any given year, particularly among Medicare enrollees, public payers are uniquely positioned to promote specialty care redesign and champion improved coordination between specialists.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Many federal, state, and private sector payers are experimenting with innovative care delivery and payment models that require shared accountability and coordination between clinical and non-clinical providers to improve quality of care, alter patterns of health care utilization that may lower health care costs outright or at least slow the trajectory of cost growth, and improve patient and provider experience. Until recently, many of these models, such as the patient-centered medical home or the accountable care organization, have assigned the primary care provider (PCP) as the central player in delivery system redesign efforts. These models build on the notion that PCPs are, or at least should be, the first point of contact in the health care system and that they are often the most frequent point of contact with the health care system.1 Indeed, in a national survey of ambulatory medical care visits, 54% of visits were for primary care, 27% were for medical specialists, and 19% were for surgical specialists.2

Yet, not all patients routinely rely on a PCP for most of their care.1, 3, 4 Clinical need, personal preferences, availability of specialists, and ease in accessing specialty care influence patients’ decisions about when and from whom they receive their medical care. For example, analyses of Medicare claims data have shown that some Medicare enrollees will more frequently visit a specialist than a PCP in a given year,5, 6 and findings from analyses of a national survey of ambulatory visits indicate that some specialists self-identify as their patients’ PCP.4 Other research has shown that visits to specialists often focus on routine or preventive care, and some of this care could be managed in primary care but for many reasons are instead managed by specialists.7, 8

Insurance coverage, in particular, plays a key role in how individuals access care and who they access for a given health need. For example, greater morbidity among Medicare and Medicaid patients suggests greater need for specialists relative to younger, healthier privately insured populations, yet specialists are less likely to participate as a Medicaid provider.9

Historically, medical specialists have received less attention in payers’ efforts to introduce more provider accountability and transform care. This is beginning to shift as the public payers, like Medicare and state Medicaid programs, and private payers have introduced demonstration projects focused on specialty care coupled with payment reforms designed to improve quality, coordination, and costs of care.10 Examples include oncologists in the Oncology Care Model and nephrologists in the Comprehensive End-Stage Renal Disease Care Model.11,12,13

Revisiting how individuals use specialty versus primary care is particularly timely as payers shift towards multi-specialty approaches to accountable care. Previous research has relied on claims data within specific insured populations, like Medicare enrollees only, and surveys of ambulatory visits and providers to investigate how the US population relies on specialists either as part of a multidisciplinary care team or as the primary provider of an individual’s medical services. This study extends this body of literature by analyzing a nationally representative survey of individuals, the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, to describe the type of provider, primary care or specialist, most often seen by individuals, to test associations between type of provider most often seen and insurance coverage, and to test associations between the number of primary care (or generalist) and specialist visits and insurance coverage.

METHODS

Data and Study Population

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of the 2013–2016 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). Through in-person interviews, MEPS collects data on the type and frequency of health care use and related medical expenditures among a nationally representative sample of noninstitutionalized US civilian families and individuals. MEPS is administered by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and utilizes a 2-year panel design in conjunction with stratification, clustering, and oversampling of specific subpopulations.14 MEPS includes data on the number of office-based and outpatient medical provider visits made by surveyed individuals, provider specialty, sociodemographic characteristics, insurance coverage, and clinical characteristics such as primary diagnoses when receiving medical care. MEPS survey data were pooled across 4 years to increase the sample size available for analysis.

To be eligible for the study, individuals had to be enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, Medicare and Medicaid, private insurance, or be uninsured for 9 or more months out of a calendar year. Individuals dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid were included as a subgroup of interest because policy makers may be particularly interested in this group’s experience accessing primary and specialty care given their unique health needs and additional vulnerabilities like having lower income. Individuals with another type of insurance not included in the list above (e.g., TRICARE) were excluded from the study sample because of their small numbers.

The study sample size varied by analysis. To describe which type of provider was most often seen, 77,292 individuals who incurred outpatient or office-based medical visits were included. Some individuals had a tie between the number of generalist and specialist visits, and while they were included in descriptive statistics, they were excluded from regression analyses that test the association between insurance type and the likelihood of seeing specialists most often. Therefore, the final sample size for that regression analysis was 71,402.

To examine the association between insurance type and counts of generalist and specialist visits, individuals who did not experience any generalist or specialty care visits and those individuals who had a tie between the number of generalist and specialist visits were included in order to accurately reflect the distribution of visits, including zero visits, in the study sample. The final sample size for that regression analysis was 79,518. The datasets analyzed for this current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Independent Variable: Type of Insurance Coverage

Type of insurance coverage—Medicare, Medicaid, Medicare-Medicaid, private insurance, or uninsured—was the primary variable of interest. An individual had to be covered by a particular insurance coverage for at least 9 months in the calendar year to be categorized as having that coverage.

Dependent Variables: Predominant Provider Type, Generalist Visits, and Specialty Care Visits

The predominant provider type was defined as the provider type (generalist or specialist) who the beneficiary saw most frequently for outpatient and office-based medical visits in the calendar year. Table 1 summarizes the provider specialties assigned as generalist and specialist. Visits to surgeons, including surgical specialists, radiologists, pathologists, hospitalists, physical medicine/rehabilitation specialists, or anesthesiologists were not considered in this analysis because a person’s need for these specialties is often time-limited. Visits to specialists labeled as “other” in the MEPS visit data were also not considered; without knowing the specialty, a determination could not be made as to whether an individual could be expected to have an extended relationship or a more limited interaction with a specialist.

The annual number of outpatient and office-based medical provider generalist and specialist visits were calculated for each individual in each calendar year. Visits were reported by the survey respondent and recorded in the MEPS outpatient visits and office-based medical provider visits files, and we categorized them as generalist or specialist based on the specialty types described in Table 1.

Statistical Analysis

Frequencies were used to describe the provider type most often seen by individuals. Multivariate, logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between insurance coverage type and the odds of seeing specialists most often. Multivariate, negative binomial regression was used to assess the relationship between insurance coverage type and counts of generalist and specialist visits. Both analyses controlled for the following sociodemographic characteristics: sex, age, education, whether or not the individual was a child or adult, race, ethnicity, geographic region of residence, self-reported income, employment status, presence of a usual source of care, self-reported physical and mental health status, presence of a functional limitation, and the number of chronic condition (up to 10 conditions). To better understand how sociodemographic characteristics were associated with predominant provider type within a particular insurance coverage group, regression models were stratified by type of insurance coverage.

Stata 11.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) survey routines were used to adjust standard errors to account for MEPS’ use of a panel design, stratification, and clustering and to apply population sample weights that were adjusted to reflect the use of multiple survey years in a pooled sample.15

RESULTS

Table 2 describes the sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample, by type of provider most often seen. Relative to individuals who most frequently saw specialists or who saw specialists and generalists the same number of times, individuals who most frequently saw generalists were younger, non-white or reported Hispanic ethnicity, self-reported less income, and self-reported excellent physical and mental health. Individuals who most frequently saw specialists or who tied in their specialist and generalist visits were more likely to report more functional limitations, have more chronic conditions, and be covered by Medicare; these differences are unsurprising given that this group is older than the group who primarily saw a generalist.

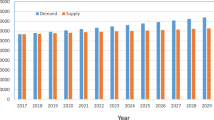

As described in Table 3, among the entire study sample, 55% of individuals predominantly visited generalists, 36% predominantly visited specialists, and 8% tied, by having the same number of generalist and specialist visits. Among individuals who primarily visited generalists, most of their primary care visits were to PCPs practicing general medicine (Fig. 1), and 80% of individuals visited only one particular type of primary care provider (e.g., a general medicine practitioner). Furthermore, 24% of individuals who primarily visited generalists also visited one or more specialists. Among individuals who primarily visited specialists, most specialty visits were to obstetricians/gynecologists, followed by ophthalmologists, psychiatrists, and orthopedists (Fig. 1). Almost half of these individuals (48%) visited only one type of specialist, 26% visited two different types of specialists (e.g., psychiatrist and dermatologist), 13% visited three types of specialists, and 13% visited four or more types of specialists. An estimated 47% of individuals who primarily visited specialists did not visit any generalists in the year.

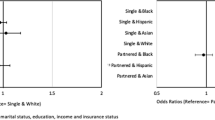

Individuals enrolled in Medicaid, Medicare-Medicaid, private insurance, and the uninsured showed a similar pattern of visiting generalists more often than specialists. In contrast, 50% of Medicare enrollees predominantly saw specialists, and 40% predominantly saw generalists. In covariate-adjusted regression models, Medicare enrollees had greater odds of visiting specialists more often than those with private insurance (OR = 1.31, 95% CI 1.18–1.44). Medicare-Medicaid enrollees and the uninsured had lower odds of visiting specialists more often than the privately insured (Medicare-Medicaid OR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.65–0.86 and uninsured OR = 0.66; 95% CI 0.59–0.74). In addition to insurance coverage being associated with having specialists as the predominant type of provider, being female and having a functional limitation were the two sociodemographic characteristics associated with higher odds of having a specialist as the predominant provider; being less than 18 years of age, in poverty, being of minority race/ethnicity, and having a usual source of care were characteristics associated with lower odds of having specialists as the predominant provider (Fig. 2).]-->

Given the greater morbidity of the Medicare population, we find, unsurprisingly, that Medicare enrollees and Medicare-Medicaid enrollees had the largest number of annual visits, 8.6 visits and 9.4 visits, respectively, whereas the uninsured reported the lowest number of visits at 3.4 (Table 3). Compared to individuals with private insurance, Medicare enrollees had 13% (95% CI 8–18%) more generalist visits and 35% (95% CI 29–48%) more specialist visits, and Medicare-Medicaid enrollees had 38% (95% CI 29–48%) more generalist visits and 15% (2–30%) more specialist visits. Medicaid enrollees had 21% more specialist visits than those who were privately insured (95% CI 12–32%), but Medicaid enrollees did not have more generalist visits than those who were privately insured (IRR = 1.04; 95% CI 1.00–1.09). Figures 1 and 2 in the Appendix depict the association between sociodemographic characteristics and the number of generalist and specialist visits.

Because children and adults do have different morbidity profiles, we examined results by children and adults separately. Adults showed patterns similar to the overall study population (Table 1 in the Appendix). Having Medicare or Medicaid was associated with greater odds of having specialists as the predominant provider, whereas having no insurance was associated with lower odds of a specialist predominant provider. Among children, having Medicaid or having no insurance was associated with lower odds of having specialists as the predominant provider relative to having private insurance (Table 2 in the Appendix).

DISCUSSION

This analysis provides a picture of primary care and specialty care use among the US general population and within different insurance coverage types. In summary, this MEPS analysis showed that individuals visit generalists more often than they do specialists, a finding similar to results from a national survey2 and several payer-specific claims-based analyses.5, 6 The distribution of visits across provider types revealed some interesting patterns. For example, almost one-quarter of individuals who mainly visit generalists also visit one or more specialists. In contrast, almost half of individuals who most often visit specialists do not have a primary care visit in the year. For these individuals, the singular reliance on specialists may be entirely clinically appropriate given a particular chronic condition, and these individuals’ specialists may be well-positioned to engage in the care planning and coordination that may be incumbent on them as the primary point of contact in a specialty care focused alternative payment or redesign effort.

This analysis also showed that combining all insurance types together masks several interesting findings. For example, Medicare enrollees were the only insured group who were more likely to have a specialist as the predominant provider. Enrollment in Medicare, Medicaid, or Medicare and Medicaid insurance was also associated with higher incidence of specialist visits. Given that these populations have certain sociodemographic characteristics such as lower income and greater morbidity that are directly correlated with clinical and social need, our finding that Medicare and/or Medicaid enrollment is associated with more specialist use is not unexpected. Medicare, in particular, and more recently some state Medicaid programs have been advancing several mandatory and optional payment model reforms for select specialists and their patients,16 and our findings suggest that this effort is well-placed.

There are important considerations when interpreting these results. Individuals surveyed by MEPS report on visits to providers; there may have been over or underreporting of visits, which could bias results. For this study, we were also unable to report on the specialty of the specific provider most frequently visited by an individual because MEPS does not record unique provider identifiers in publicly available data. As a result, we can only conclude that certain specialties were more frequently or less frequently seen, but we cannot identify an individual’s specific provider most frequently seen and the specialty of that specific provider. Finally, this was a cross-sectional, descriptive study, and unmeasured confounding may bias results describing the association between insurance type and type of provider most frequently seen. For example, need for specialty care cannot be controlled for in this descriptive analysis. For Medicaid enrollees, in particular, there are known barriers to accessing specialty care, including difficulty finding a specialist willing to take Medicaid, and if an individual can find a specialist, long wait times for an appointment and missed appointments.9, 17,18,19,20 Given these barriers, self-reported use of specialty care for Medicaid enrollees may not align with actual need for specialty care.

CONCLUSION

These results suggest that use of specialty care and use of different specialists at the same time is quite common, so efforts to bring more types of specialists into the delivery system and payment reform should continue. However, caution is warranted to not silo specialists from primary care and from one another. Much like primary care medical homes have been tasked with improving knowledge transfer and referral management between primary care and specialists, delivery system redesign for some specialties may need to encompass outreach to and coordination with other specialists when coordination is clinically indicated. The National Committee for Quality Assurance’s patient-centered specialty practices program has championed improved coordination among specialists, but uptake of the program has been fairly slow.21, 22 Emerging efforts to focus on patients’ total costs of care may hold promise for energizing coordination. If primary care providers, specialty care providers, and institutional providers (hospitals and long-term care providers) are tasked with transforming together in a coordinated, patient-centered way, effecting change in total spending may be more feasible than placing sole responsibility for cost containment on one group of providers.

References

Starfeld B. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2016 national summary tables. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. n.d. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2016_namcs_web_tables.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2019.

Forrest CB. A typology of specialists' clinical roles. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(11):1062–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.114.

Edwards ST, Mafi JN, Landon BE. Trends and quality of care in outpatient visits to generalist and specialist physicians delivering primary care in the United States, 1997-2010. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):947–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2808-y.

Pham HH, Schrag D, O'Malley AS, Wu B, Bach PB. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(11):1130–9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa063979.

Romaire MA, Haber SG, Wensky SG, McCall N. Primary care and specialty providers: an assessment of continuity of care, utilization, and expenditures. Med Care. 2014;52(12):1042–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000246.

Valderas JM, Starfield B, Forrest CB, Sibbald B, Roland M. Ambulatory care provided by office-based specialists in the United States. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(2):104–11. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.949.

Clough JD, Patel K, Shrank WH. Variation in Specialty Outpatient Care Patterns in the Medicare Population. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(11):1278–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3745-8.

MACPAC. Medicaid Access in Brief: Adults’ Experiences in Obtaining Medical Care. Washington, DC: MACPAC. 2016. Available at: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Adults-Experiences-in-Obtaining-Medical-Care.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2019.

McClellan M, Muhlestein D, Saunders R, Richards R. Recent progress in the value journey: growth of ACOs and value-based payment models in 2018. Health Affairs Blog. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1377/hblog20180810.481968.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Oncology care model. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2019. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/oncology-care/. Accessed August 22, 2019.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative: general information. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2019. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/. Accessed August 22, 2019.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Comprehensive ESRD care model. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2019. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/comprehensive-esrd-care/. Accessed August 22, 2019.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey—MEPS HC-192: 2016 full year consolidated data file. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2018. Available at: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h192/h192doc.shtml. Accessed August 22, 2019.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey—MEPS HC-036: 1996–2016 pooled linkage variance estimation file. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2018. Available at: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h36/h36u16doc.shtml. Accessed August 22, 2019.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: innovation center new direction. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2019. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/direction/. Accessed August 22, 2019.

Felland LE, Lechner AE, Sommers A. Improving access to specialty care for Medicaid patients: policy issues and options. Washington, DC: The Commonwealth Fund. 2013. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2013_jun_1691_felland_improving_access_specialty_care_medicaid_v2.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2019.

Cunningham PJ, O'Malley AS. Do reimbursement delays discourage Medicaid participation by physicians? Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(1):w17–28. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.w17.

Holgash K, Heberlein M. Physician acceptance of new Medicaid patients: what matters and what doesn’t. Health Affairs Blog. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1377/hblog20190401.678690.

Zuckerman S, Skopec L, Epstein M. Medicaid Physician Fees after the ACA Primary Care Fee Bump. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2017.

National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). Practices. Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). 2018. [cited August 6, 2019]. Available from: https://reportcards.ncqa.org/#/practices/list?recognition=Patient-Centered%20Specialty%20Practice. Accessed 22 Aug 2019.

National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). NCQA Patient-Centered Specialty Practice (PCSP) Standards and Guidelines. 1 ed. Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA); 2019.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Jean Hastie for her programming assistance.

Funding

This study was funded by RTI International.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that she does not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 142 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Romaire, M.A. Use of Primary Care and Specialty Providers: Findings from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 2003–2009 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05773-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05773-7