Abstract

Background

To ensure a next generation of female leaders in academia, we need to understand challenges they face and factors that enable fellowship-prepared women to thrive. We surveyed woman graduates of the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program (CSP) from 1976 to 2011 regarding their experiences, insights, and advice to women entering the field.

Methods

We surveyed every CSP woman graduate through 2012 (n = 360) by email and post. The survey, 12 prompts requiring open text responses, explored current work situation, personal definitions of success, job negotiations, career regrets, feelings about work, and advice for others. Four independent reviewers read overlapping subsets of the de-identified data, iteratively created coding categories, and defined and refined emergent themes.

Results

Of the 360 cohort, 108 (30%) responded. The mean age of respondents was 45 (range 32 to 65), 85% are partnered, and 87% have children (average number of children 2.15, range 1 to 5). We identified 11 major code categories and conducted a thematic analysis. Factors common to very satisfied respondents include personally meaningful work, schedule flexibility, spousal support, and collaborative team research. Managing professional-personal balance depended on career stage, clinical specialty, and children’s age. Unique to women who completed the CSP prior to 1995 were descriptions of “atypical” paths with career transitions motivated by discord between work and personal ambitions and the emphasis on the importance of maintaining relevance and remaining open to opportunities in later life.

Conclusions

Women CSP graduates who stayed in academic medicine are proud to have pursued meaningful work despite challenges and uncertain futures. They thrived by remaining flexible and managing change while remaining true to their values. We likely captured the voices of long-term survivors in academic medicine. Although transferability of these findings is uncertain, these voices add to the national discussion about retaining clinical researchers and keeping women academics productive and engaged.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

“Sometimes you need to climb out a window, and scale the fire ladder, to get to the place you want to be.”-Reflection of a Woman RWJ CSP Graduate

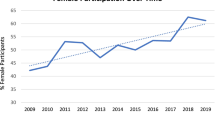

The USA needs physicians ready and willing to conduct critical health services research, inform healthcare policy, and lead healthcare reform.1 Women are critical to this workforce but are not proportionately represented in the leadership pipeline. In 2017, for the first time, the majority (50.7%) of new enrollees in medical schools were women and as of 2019 women represent a majority (50.5%) of enrolled medical school students.2, 3 However, only 25% of tenured full professors and 18% of academic department chairs are women.4 The appointment of women to senior leadership positions has not kept pace with that of men even when adjusting for the established criteria for academic success (i.e., number of publications, grant dollars awarded, hours worked, salary).5, 6 The cause of gender disparities is multifactorial and highly complex.7, 8 Institutional policies intended to address gender imbalance (e.g., flexible work hours, shared jobs, altered tenure clocks, onsite childcare) fail to keep qualified women in academic medicine.

There is a leaky academic medicine pipeline. Over 40% of first-time assistant professors of any gender, with full-time faculty appointments at academic medical schools, leave academia within 10 years.9 Fewer women enter MD/PhD programs and there are greater attrition rates among women than men.10, 11 Women who have completed advanced training face substantial challenges—including extraprofessional demands that are in direct conflict with career critical events such as academic promotion, and limited access to mentoring and opportunities—which perpetuate the underrepresentation of women in leadership positions.6, 12 And yet, some survive and thrive in academia. A nuanced understanding of the challenges and strategies that have enabled women to stay productive and satisfied in academic medicine would provide models for people of all genders seeking impactful careers.

The Robert Wood Johnson (RWJ) Foundation initiated the Clinical Scholars Program (CSP) in 1972 to train post-residency physicians as change agents in transformation of the quality of American healthcare by providing 2 years of training in health services research and healthcare policy.13, 14 Graduates of the RWJ CSP represent a highly motivated and exquisitely well-prepared group of physicians who have received rigorous research training and have had access to a rich network of mentors and influence leaders. The program has been successful. As of 2014, there had been approximately 1272 graduates (approximately 25% are women); 75% of graduates take academic jobs right out of the program. CSP graduates include department chairs, numerous state and city commissioners of health, university deans, Chief Executive Officers in industry, and influential health quality agency directors at all levels of government.15,16,17

Previously, in 2006, we reported on the sources of career satisfaction among a 1984–1989 cohort of women CSP graduates. For that group of 16 (74% response rate) fellowship-prepared, mid-career academic women physicians, job satisfaction was defined by achieving a personally rewarding professional and personal life balance.18 In this study, we expand on our prior work to include women who entered professional life across a span of 35 years borrowing methods from interpretive phenomenology to understand the complexity and challenges of creating personal/professional satisfaction in academic medicine for fellowship trained women by analyzing written text responses to a structured survey.19

METHODS

Researcher Reflexivity

The interpretive phenomenology framework explicitly acknowledges that researchers’ backgrounds and perspectives affect what they choose to study, the methods they use, the findings considered important, and how they interpret those findings and frame their conclusions.19, 20 To be transparent about our perspectives and pre-conceived ideas, we documented, in our Institutional Review Board application, predictions for our findings based on prior work and personal experiences as women physicians in academic medicine (AK, NB, KF are RWJ CSP graduates; JR, RD, PL, KS are not), two social science graduate students (KS, PL) and an undergraduate student (RD) (see Appendix 2).

Subjects

Using the RWJ Clinical Scholars directory maintained by the RWJ Foundation, we identified 360 women who graduated from the program from its inception in 1974 up through and including the graduating class of 2011. Using a variety of methods, we obtained last known email and home mailing address. Gender was categorized based on first name and when unclear, by checking with program administrative staff. Gender identity was not confirmed with the respondents.

Data Collection Instrument

The survey instrument, modified from the one used in the 2006 study, included 12 prompts (see Appendix 1) requiring open text responses to questions designed to explore current work situation, personal definitions of success and accomplishments, job negotiations, career regrets or disappointments, predominant feelings about work, and advice for others. To minimize respondent burden, we limited the demographic data we collected to age, CSP graduation year, marital status, and number of children. We sent the survey as a URL for a Qualtrics™ form by email and a hard copy post with a detailed cover letter along with a copy of the previously published paper.18 Our instrument was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Responses received in hard copy were entered into a Qualtrics data set by a research assistant (KS) who de-identified the text. In two cases, at the explicit request of the respondent, the research assistant conducted a phone interview using the same 12 prompts, recording and transcribing the answers.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Four independent readers (AK, NB, KF, JR) conducted a content analysis of overlapping subsets of the data, each summarizing findings in a separate document. Iteratively, through discussion and sharing of documents, we created a descriptive coding scheme to fit the data. All coders took extensive notes as they read the transcripts to provide a transparent record of justifications for choices, perspectives, and biases as we refined the definitions of each code category. We intentionally avoided applying the coding categories previously developed in the 2006 study (AK, NB, KF were involved in the 2006 study; JR, KS, RD, PL were not). We continued this process until no new codes were needed to describe the data. Coding of text was not mutually exclusive; any chunk of text could be coded into a number of categories. Two readers (AK, KS) applied these codes to the entire data set using Dedoose™ qualitative analysis software (kappa − .04 to .70, pooled kappa .35). A final coding framework was refined through intermittent checks of rater agreement and discussion of disagreements between the coders and among the whole group. We defined 35 unique codes and had 1132 code applications made to 643 excerpts of the text.

Because we were interested in exploring the complexity and challenges of creating personal/professional satisfaction in academic medicine for fellowship trained women, we conducted rounds of “axial” coding aimed at relating codes (categories and concepts) to each other in thematic groups. This process continued until no new themes emerged.

RESULTS

After 6 reminders, 108/360 (30%) of the cohort responded. Of the non-survey respondents, one explained that this was due to the demands of a new high-profile job; otherwise, there were no returned mail or emails. The mean age of respondents was 45 (range 29 to 65); 6% were single, 85% partnered, 8% divorced/separated, and 87% had children (average number 2.13, range 1 to 5). Table 1 presents themes, subthemes, and exemplar quotes. While most findings applied across the entire group of 108 without a discernable pattern, we did notice that a small number of codes and themes were only found among the 20 respondents who completed the CSP prior to 1995—approximately the mid-point of graduation for the cohort—and we note when this is so. Below we define and illustrate the themes.

Defining Success Is Complex

We explicitly asked our respondents about their definitions of success. The majority of all respondents reported feeling successful, satisfied, and appreciative of the “freedom of academics.” However, there were many caveats. One woman noted she was “Very satisfied but would prefer if what I have chosen as my life’s work was better recognized by university system and tenure and promotion system.” Another woman expressed uncertainty that the effort to pursue a career in academic medicine would be worthwhile: “… there’s so much uncertainty right now in clinical research. A track record of productivity is not worth much without research funding, yet funding is so scarce now that the time investment needed … to secure it may be too exorbitant.”

Many respondents, proud of their ability to survive and thrive as researchers, talked of “learning to play the game without taking it personally,” becoming savvy about recognizing threats to career viability, and the challenges of obtaining funding and of writing.

Creating Balance

Most respondents characterized personal/professional balance as becoming highly efficient at work, setting limits at home and work, and being deliberate about when to become a parent or choosing to remain childless. In contrast to our pre-study prediction (see Appendix 2), the majority of respondents assumed it was their responsibility to maintain this balance and that they would need to do so without any institutional support.

Respondents described a range of family task sharing models (e.g. “50:50” between partners, “I am the captain of the ship,” “I am the General Contractor,” “I do it all,” “I contract it all out”). As expected, strategies implemented to manage personal/professional balance were specific to stage of career and age of children. Nine respondents reported that their partner is or was the primary parent.

Many types of flexibility were seen as crucial to thriving in academic medicine. Interestingly, a number of women commented that “You can always be a doctor,” seeing clinical work as the safety net if research was unsustainable. A number of the women remarked on the importance of research as the source of critical flexibility that sustains an academic career as described by this respondent:

“I believe that the flexibility of being a researcher contributes to my ability to care for my family and take care of life at home... I can make it to… school events..., appointments, etc.”

Managing Change and Tolerating Chaos

Respondents told detailed stories about managing unpredictable life events such as death or disability of a spouse, child, or parent and divorce (“be careful whom you marry”), and shared coping strategies. Women emphasized the need to diversify research funding and create strong collaborations. In a small number of cases, personal challenges forced a significant career change as for a woman who left academia when she had children because “the University I was employed by made unreasonable demands on women with young children.”

Career as an Ongoing Negotiation

As prompted, each respondent gave advice on how to negotiate or renegotiate a job. Most women emphasized that negotiation was a professional skill used daily, not an isolated event. The messages include, “if you don’t ask you won’t get what you want,” and acknowledgment that there are barriers to both knowing what you will need and being empowered to advocate for yourself as reflected in this quote:

“Wish I were more aggressive about asking for what I want and need for my career advancement. Even though I have accomplished more than most of my male colleagues, I haven’t been as successful at parlaying that into more promotion(s) and resources.”

Collaboration as a Key Component of Success

Respondents emphasized a variety of models for effective collaboration and acknowledged that political savvy is required. One woman wrote:

“I’ve built a very high- functioning team (and we have some fun too). Everyone takes ownership in their work and is committed to the project. It has definitely been a struggle at times, and I’ve made it through.” Respondents acknowledged there are costs “of doing it for the team.” For example, one woman said, “I accepted that the usual administrative responsibilities at the University didn’t leave enough time for research.”

Most women emphasized the need to invest in relationships. Women talked about exerting significant effort to create “family at work,” acknowledging that who they worked with on a day-to-day basis was critical to success. Receiving adequate and supportive mentoring, having access to productive collaborations, and having a “good, supportive boss” were noted as essential elements of success.

Mentoring Matters

Almost all respondents discussed mentoring or being mentored. In general, they endorsed that mentoring is highly impactful and related to a sense of success and satisfaction with one’s work. Women who felt they did not find appropriate mentors, especially immediately following their CSP graduation, reported a sense of deprivation even though they eventually became highly successful, as in this quote:

“I regret my choice of research mentor - and wish I had found someone who not only ‘cheered me on’ but (more importantly) facilitated contacts with others in our field, included me in on her research, wrote me into grants, and bothered to read and give meaningful feedback on my own work.”

Looking Back: Growing and Maturing

Many respondents hold or have held high-profile, influential leadership positions. When asked how their goals had changed over time, our subjects commonly remarked they had become both more pragmatic and courageous. Some women discussed advantages and disadvantages of seeking titled administrative leadership roles. They noted that official positions provided the influence to set a workplace tone that enabled flexibility for others that is essential to career success in academics. On the other hand, some women acknowledged that taking on leadership roles comes at the risk of losing the hard-earned autonomy and flexibility needed to conduct research.

As members of the first generation of women to break into academic medicine in significant numbers, many of the respondents who graduated prior to 1995 discussed having to navigate their entire careers with precious few women role models. These women took great pride in having learned “how the system really works” and continue to experience themselves as “on their own” as reflected in the following quote: “After achieving all that I envisioned as a RWJCS -- we now wonder, ‘what is next?’ We don’t seem to have the role models for this next stage of our career.”

DISCUSSION

Lessons Learned

These 108 women’s voices, representing graduates from the RWJ CSP over a 35-year period, reveal critical lessons for retaining and advancing the physician-scientist workforce. Much of how women define success and navigate work and life remains unchanged from our earlier and much smaller study and aligns with the findings of others.18 Now, as then, women create paths to make life work for them while remaining true to their own definitions of success. Very satisfied respondents are likely to describe work as deeply meaningful and have egalitarian spousal relationships. They have mentors who provide support and critical networking, and create collaborative work and family environments. They devise strategies to attain and maintain time flexibility. However, despite an increasingly challenging funding environment and a change in generational expectations, implementing these strategies is still viewed as the sole responsibility of the individual woman rather than one shared with institutions. Help, in the form of institutional policies and programs, is needed to keep these well-trained women physician-scientists productive and engaged or we are at risk of losing their contributions.1

Themes prominent for the relatively few women who graduated prior to 1995, an admittedly small but highly experienced group, included remaining open to new opportunities, building teams to do multidisciplinary collaborative research work, valuing a wide range of relationships, and seeking ongoing meaningful work in later life. In this sample, women appointed to senior leadership positions have needed to be particularly independent and enterprising in the face of significant barriers (e.g., interpersonal sexism, gender-based structural discrimination, fewer opportunities, and gender discordant mentoring). In retrospect, these women wished they had negotiated their jobs more effectively, having experienced the consequences of the fact that women physician-scientists earn less money than men and are less likely to attain administrative leadership positions—a disparity that has been shown to be especially true at top-ranked, research-intensive institutions.21 There is evidence that women do not take full advantage of institutional efforts to address gender inequity because of concerns about stigma.22 Women in this study appreciate the complex interplay among personal skills, institutional discrimination, and societal sexism and wish they “were more assertive, negotiated better, had ... A ‘wife.’” This sentiment continues to hold power among rising women physician leaders.23 Finally, while the need for promotion and support of senior women into traditional leadership positions has been discussed, there is a paucity of literature about creating satisfying alternative career paths for senior women (e.g., paid mentor roles, meaningful part-time faculty positions).

Women CSP graduates, as expected, are very concerned about the increasing competition for external research funding. While women who graduated from the CSP since 1995 may have benefited from a clearer path to research success (e.g., formal mentoring, “K to R” programs and federal Clinical Translational Science resources), the younger generation has been characterized as having higher expectations of equity in relationships and at work, prioritizing work life balance, and as more likely to have life partners involved with child rearing and home maintenance than their senior colleagues.24, 25 At the same time, the younger generation faces dwindling research support and increased pressure on physicians to generate revenue for their salary through patient care, a less flexible commitment. A few programs aimed at addressing issues facing women in academic medicine have emerged, including the Doris Duke Fund to Retain Clinical Scientists (DDFRCS), which has funded 10 US medical schools to implement a 5-year program focusing on preventing the attrition of early-career physician-scientists from research by providing supplemental, flexible funds to promising early-career physician-scientists with extraordinary extraprofessional caregiving demands.26 Early evidence suggests that this program is having a positive impact on the small group that has access and qualify.25

Institutions should provide time, task, and project management coaching and strive to ensure clinicians have predictable schedules because these strategies support academic women in managing the demands of a research career.27 Some of our respondents, who were hospital-based physicians, mentioned that regulations on resident work hours and other limitations in clinical resources have resulted in a greater clinical burden on them as physician-scientists. This instability stresses researchers who do not have the personal resources to continue in academic work. These women desire mentoring that is not only personally supportive but provides access to resources, opportunities, and a network of relationships at work that provide a safety net. Others have identified that this sponsorship or active and pragmatic advocacy is probably even more important that traditional mentorship in the advancement of women in academic medicine.8 Promising multipronged institutional programs with ambitious goals for gender equity are emerging.

Limitations

Our data represents only the experience of long-term survivors in academic medicine who had the time and interest to respond. For pragmatic reasons, we chose to collect data using a semi-structured survey rather than in-depth interviews, trading depth for breadth. Therefore, transferability of these findings to other groups is uncertain. On the other hand, we used purposive sampling of the women physicians with the shared experience of having had been selected into and completed the RWJ CSP, and a rigorous text analysis approach focused on the respondents’ perspectives on the challenges and facilitators of career satisfaction. We took great care to understand and describe the text responses, through multiple rounds of coding and consensus building across 5 readers from a range of institutions and continued the interpretive process iteratively through the process of writing of this manuscript. Another serious limitation of this work is that we did not confirm gender identity with study participants. In a next phase of this study, we plan to elicit responses of graduates of the RWJ CSP to our findings by sharing this manuscript and assessing career paths and outcomes in more detail.

CONCLUSION

The experiences and views of this cohort of well-trained women clinician scientists offer important lessons to those interested in repairing the leaky pipeline of clinical researchers. In addition to actively ensuring salary parity, young researchers need the kind of excellent mentorship and sponsorship that can be bolstered through formal mentor training; access to more research funding in general as well as more flexible bridge funding or “helping hands” funding when life events or responsibilities inevitably arise; and will likely benefit from explicit efforts to address gender discriminating environments through active recruitment of diverse candidates and retention of experienced mentors. It should be noted that the challenges and inequities faced by the women represented here may be experienced in different or greater ways by women of color and transgender and non-binary individuals, and further research is needed to understand these experiences. Institutional culture or structural solutions which force us to redefine the “ideal worker” and academic success would help people of all identities across the career span.28

References

Salata RA, Geraci MW, Rockey DC, Blanchard M, Brown NJ, Cardinal LJ, et al. U.S. Physician-Scientist Workforce in the 21st Century: Recommendations to Attract and Sustain the Pipeline. Acad Med. 2018;93(4):565–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001950

AAMC. More Women Than Men Enrolled in U.S. Medical Schools in 2017. AAMC News: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2017.

Boyle P. More women than men are enrolled in medical school. AAMC News: Association of American Medical Colleges. 2019. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/more-women-men-are-enrolled-medical-school.

Paturel A. Where are all the women deans? AAMC News: Association of American Medical Colleges. 2019. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/where-are-all-women-deans

Jagsi R, Guancial EA, Worobey CC, Henault LE, Chang Y, Starr R, et al. The “gender gap” in authorship of academic medical literature--a 35-year perspective. N Engl J Med 2006;355(3):281–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa053910

Jagsi R, DeCastro R, Griffith KA, Rangarajan S, Churchill C, Stewart A, et al. Similarities and differences in the career trajectories of male and female career development award recipients. Acad Med 2011;86(11):1415–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182305aa6

Morahan PS, Rosen SE, Richman RC, Gleason KA. The leadership continuum: a framework for organizational and individual assessment relative to the advancement of women physicians and scientists. J Women's Health (Larchmt) 2011;20(3):387–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2010.2055

Bates C, Gordon L, Travis E, Chatterjee A, Chaudron L, Fivush B, et al. Striving for Gender Equity in Academic Medicine Careers: A Call to Action. Acad Med 2016;91(8):1050–2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001283

Faculty Roster: 10-Year Attrition Rates and 10-Year Promotion Rates: AAMC2019.

Andriole DA, Whelan AJ, Jeffe DB. Characteristics and career intentions of the emerging MD/PhD workforce. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1165–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.10.1165

Andrews NC. The other physician-scientist problem: where have all the young girls gone? Nat Med 2002;8(5):439–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nm0502-439

Soklaridis S, Zahn C, Kuper A, Gillis D, Taylor VH, Whitehead C. Men’s Fear of Mentoring in the #MeToo Era - What’s at Stake for Academic Medicine? N Engl J Med 2018;379(23):2270–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMms1805743

Kumar B. The Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program: Four decades of training physicians as agents of change. Virtual Mentor 2014;16(9):713–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/virtualmentor.2014.16.09.medu1-1409

Bromley E, Jones L, Rosenthal MS, Heisler M, Sochalski JA, Koniak-Griffin D, et al. The National Clinician Scholars Program: Teaching Transformational Leadership and Promoting Health Justice Through Community-Engaged Research Ethics. AMA J Ethics 2015;17(12):1127–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2015.17.12.medu1-1512

Voelker R. Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Mark 35 years of health services research. JAMA. 2007;297(23):2571–3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.23.2571

Kleinman LC, Runyan DK. Moving the discourse on quality in pediatrics: recent contributions of Robert Wood Johnson Foundation clinical scholars. Pediatrics. 2013;131 Suppl 1:S1–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1427b

Gee RE. Disruptive innovation in obstetrics and gynecology: the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program (1972-2017). Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2014;26(6):493–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/GCO.0000000000000128

Kalet AL, Fletcher KE, Ferdman DJ, Bickell NA. Defining, navigating, and negotiating success: the experiences of mid-career Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar women. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21(9):920–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00524.x

Moustakas C. Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994.

Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6

Jena AB, Khullar D, Ho O, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex Differences in Academic Rank in US Medical Schools in 2014. JAMA. 2015;314(11):1149–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.10680

Shauman K, Howell LP, Paterniti DA, Beckett LA, Villablanca AC. Barriers to Career Flexibility in Academic Medicine: A Qualitative Analysis of Reasons for the Underutilization of Family-Friendly Policies, and Implications for Institutional Change and Department Chair Leadership. Acad Med 2018;93(2):246–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001877

Winkel AF. Every doctor needs a wife: An old adage worth reexamining. Perspect Med Educ 2019;8(2):101–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-019-0502-9

Mercer C. How millennials are disrupting medicine. CMAJ. 2018;190(22):E696-E7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.109-5605

Jagsi R, Jones RD, Griffith KA, Brady KT, Brown AJ, Davis RD, et al. An Innovative Program to Support Gender Equity and Success in Academic Medicine: Early Experiences From the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation’s Fund to Retain Clinical Scientists. Ann Intern Med 2018;169(2):128–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-2676

Laver KE, Prichard IJ, Cations M, Osenk I, Govin K, Coveney JD. A systematic review of interventions to support the careers of women in academic medicine and other disciplines. BMJ Open 2018;8(3):e020380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020380

Robinson GF, Schwartz LS, DiMeglio LA, Ahluwalia JS, Gabrilove JL. Understanding Career Success and Its Contributing Factors for Clinical and Translational Investigators. Acad Med 2016;91(4):570–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000979

Howell LP, Beckett LA, Villablanca AC. Ideal Worker and Academic Professional Identity: Perspectives from a Career Flexibility Educational Intervention. Am J Med 2017;130(9):1117–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.06.002

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the women RWJ Clinical Scholars who took the time to share their thoughts with us as well as all those who were unable to respond but have supported us in this work in other ways. We appreciate the financial support provided to this project by the RWJ Foundation and the guidance provided by then CSP Program director Desmond Runyan, MD, DrPH.

Funding

We were funded, in part, with unrestricted funds from Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Our study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Presented as a poster entitled "Sometimes you need to climb out a window, and scale the fire ladder, to get to the place you want to be", at the 2014 SGIM annual meeting.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kalet, A., Lusk, P., Rockfeld, J. et al. The Challenges, Joys, and Career Satisfaction of Women Graduates of the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program 1973–2011. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 2258–2265 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05715-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05715-3