Abstract

Objective

To identify priorities for improving healthcare organization management of patient access to primary care based on prior evidence and a stakeholder panel.

Background

Studies on healthcare access show its importance for ensuring population health. Few studies show how healthcare organizations can improve access.

Methods

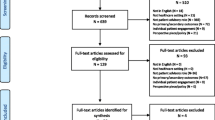

We conducted a modified Delphi stakeholder panel anchored by a systematic review. Panelists (N = 20) represented diverse stakeholder groups including patients, providers, policy makers, purchasers, and payers of healthcare services, predominantly from the Veterans Health Administration. A pre-panel survey addressed over 80 aspects of healthcare organization management of access, including defining access management. Panelists discussed survey-based ratings during a 2-day in-person meeting and re-voted afterward. A second panel process focused on each final priority and developed recommendations and suggestions for implementation.

Results

The panel achieved consensus on definitions of optimal access and access management on eight urgent and important priorities for guiding access management improvement, and on 1–3 recommendations per priority. Each recommendation is supported by referenced, panel-approved suggestions for implementation. Priorities address two organizational structure targets (interdisciplinary primary care site leadership; clearly identified group practice management structure); four process improvements (patient telephone access management; contingency staffing; nurse management of demand through care coordination; proactive demand management by optimizing provider visit schedules), and two outcomes (quality of patients’ experiences of access; provider and staff morale). Recommendations and suggestions for implementation, including literature references, are summarized in a panelist-approved, ready-to-use tool.

Conclusions

A stakeholder panel informed by a pre-panel systematic review identified eight action-oriented priorities for improving access and recommendations for implementing each priority. The resulting tool is suitable for guiding the VA and other integrated healthcare delivery organizations in assessing and initiating improvements in access management, and for supporting continued research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Providing access to healthcare is a fundamental primary care function and a necessary prerequisite for judging care quality.1 Yet, translation of the substantial research on the importance and determinants of access into sustainable access improvement in healthcare delivery organizations has lagged. Few research address the needs of organization leaders and managers for continuous, comprehensive and sustainable access management approaches. Expert panels can provide a basis for moving forward when existing research evidence is insufficient.2,3,4 We initiated a systematic review of research evidence on diverse access management interventions5 and a qualitative study of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) access manager initiative6 as part of a 2-year-long project capped by the modified Delphi panel process reported here. Our goal was to provide evidence-informed guidance on top priorities for improving management of patient access to primary care in integrated healthcare systems.

Access is a “wicked” problem.7, 8 Wicked problems require solutions that integrate across stakeholder perspectives and span relevant organizational programs and goals. No one solution to a wicked problem will succeed across organizational contexts or across time. All solutions require both trade-offs between alternative goals and ongoing monitoring. We therefore focused on access management as an ongoing organizational activity rather than on access as a once-and-done outcome. We aimed to identify the key organizational structures, processes, and outcomes9 that leaders and managers of healthcare delivery systems would need to consider for undertaking access management improvement.

Timely access to primary care is important to integrated healthcare systems, and has been the major focus of access-related performance measurement.5 Primary care provides first-line and preventive care, and is at the junction between patients and appropriate use of the wider set of available health services.10 The National Academy of Medicine identified timeliness as a fundamental aim for healthcare11—and as the least well studied and understood.12 However patient needs and preferences are at the foundation of optimal access, and from the patient’s point of view, improved access includes a broader range of considerations other than timeliness, such as availability, accommodation, affordability, and acceptability.13

Integration of patient considerations into management strategies is challenging. Patients have diverse perspectives on, for example, accessing primary care team members other than physicians, on group visits, and on non-face-to-face care such as telephone care or secure messaging. Patients may value being seen on a day of their choice, or by their continuity provider, more than they value being seen quickly—or vice versa.14 Finally, patients may weigh the effort required to achieve needed access, such as distance to clinic, waiting time, or ease of making appointments, in deciding whether and how to accomplish it.15, 16 It is thus not surprising that patient-reported access measures often do not align tightly with timeliness measures.17,18,19,20 Clearly, improving patient experiences related to access requires integration of patient and system perspectives.

Healthcare system leaders and managers as well as patients face trade-offs in approaching access improvement. The same open access actions that improve access in the short term can lead to increased demand that worsens access in the longer term.21 Maximizing timely access and continuity of care can be conflicting goals in the face of fixed primary care resources.8, 22,23,24 In turn, both the supply of services and the demand for them will be influenced by multiple and continuously changing local, regional, and national factors.

In the work presented here, we viewed achieving optimal access as a management challenge within a complex adaptive system framework. In complex adaptive systems, the results of management actions will always be subject to uncertainty8 and to unintended consequences;25, 26 step by step improvement instructions may therefore not produce the desired result. We aimed instead to use a rigorous evidence base and modified Delphi panel methods to promote the development of targeted access management improvement agendas27 by organization leaders and managers, and to promote future access management research. Our objectives were to (1) define access management; (2) identify access management priorities for action; (3) develop recommendations, suggestions for implementation, and references for each priority area; and (4) develop a panel-approved ready to use tool summarizing the results.

METHODS

Overview

The study was carried out between January 2016 and May 2018. The stakeholder panel process included data collection and analysis based on in-person panel voting and transcripts as well as five panelist surveys. Key study activities and a project timeline are provided in Table 1 and described below. Other results have been documented elsewhere.28,29,30

The study was assessed by the RAND Human Subjects Protection Committee, found to be of minimal risk, and determined to be exempt. The study was funded by the VHA.

Collection of Access Management Evidence

Prior to panel activities, we collected reports and manuals focused on how to improve access in VHA12, 31,32,33 or in other major health systems, including Canada’s and Great Britain’s.25, 26 We initiated a systematic review of access management by partnering with the Veterans Affairs (VA) Evidence-Based Synthesis Program (ESP).5 We also initiated qualitative data collection and analysis of 56 key informant interviews focused on assessing implementation of access-oriented group practice management in VHA (a congressionally mandated initiative).6

Recruitment of a Balanced Stakeholder Panel

Our stakeholder panel included 20 panelists. To identify the 20, we used the “7 P” framework (patients, providers, purchasers, payers, policy makers, product makers, and principal investigators)34 informed by an access flow chart and logic model.30 We augmented the framework to include representation of expertise in the needs of rural populations; nursing; national, regional, and front-line primary care leadership; large managed care organization policy and practice; a non-U.S. healthcare system (Canada); continuity of care; and access measurement.

Collection and Analysis of Pre-Panel Survey Data

We developed a literature-based framework of key access management domains (Table 2) and used the framework as the basis for 85 survey items to assess them. The survey asked panelists to rate the priority of addressing each goal as follows: 0 (cannot answer); 1 (very low priority); 2 (low priority); 3 (medium priority); 4 (high priority); or 5 (very high priority, must be addressed this year). We computed reviewer-adjusted (de-biased) means35 and the modal value for each item across all panelists. We identified items with substantial disagreement as requiring panel discussion, using a standard deviation (SD) cutoff of more than 0.85. The survey also asked for comments on a preliminary definition of access management.

In-Person Stakeholder Panel Meeting

Panelists attended a 2-day in-person meeting. Panel procedures adhered to consensus methods principles: anonymity (private ranking or voting to avoid dominance group processes); iteration (multiple rounds to allow panelists to change their opinions after discussions); controlled feedback (feedback of the group response); and statistical group response (central tendency and dispersion measures).36 We recorded, transcribed, and qualitatively analyzed the in-person panel discussions, including written comments.

We held five simultaneous subpanels37 of 6–7 participants in a 1.5-h breakout session during the panel meeting to consider definitions of access and refine definitions of access management.38 Subpanels included 14 guest experts in addition to panelists. Each subpanel presented their conclusions to the entire group.30

Collection of Post-Panel Survey Data

After the panel meeting, we used anonymous voting results and formal qualitative content analysis of panel transcriptions to develop revised definitions of access management. We also administered a post-panel survey to all panelists. The survey re-rated pre-panel survey high-priority items and considered new potential high-priority items based on the panel meeting. We included the 10 items from the pre-panel survey with an adjusted mean exceeding 3.75 and for which more than 50% of panelists rated the item as “very high priority.” We analyzed panel discussion transcripts, study team notes, and anonymous votes held during the meeting to identify potential item refinements and potential new panelist-suggested high-priority items. We divided the resulting 14 candidate items into structure, process, and outcome goals, following the Donabedian model,9 and asked panelists to rate whether improvement toward this goal was (a) important and urgent (i.e., should be undertaken this year); (b) important but not urgent; or (c) not important. We included all post-panel survey items rated by at least 50% of panelists as important and urgent in a final list of key priorities for action.

Development of Preliminary Evidence-Based Recommendations for Achieving Key Priorities

To develop recommendations, the study team, supported by an evidence-based practice center, used snowball queries and online searches30 to collect additional literature, including gray literature, relevant to each key priority for action. We also electronically searched the transcripts of panel discussions and the studies in the prior access management systematic review5 using terms related to each key priority. Based on these results, the study team developed preliminary recommendations and suggestions for implementation for each key priority, with references indicating the basis for each.

Revision of Priorities Based on Panelist Input

A subset of 14 of the 20 original panelists agreed to participate in reviewing and revising recommendations and suggestions for implementation prior to and during each of 2 conference calls. The 14 panelists represented 6 of the original 7 Ps (patients, providers, purchasers, payers, policy makers, product makers). The 6 declining panelists indicated their willingness to review final materials but did not wish to commit to the additional 2 calls and associated review work.

After each call, the study team used detailed notes, results of anonymous voting, and written comments to revise the recommendations. The first pre-panel call survey asked the 14 panelists whether each proposed recommendation should be included or omitted. The second pre-panel survey asked the 14 to indicate, for each included recommendation, whether the recommendation as written was acceptable or not, and to add any comments. The study team incorporated the final set of priorities, recommendations, suggestions for implementation, and references along with the revised access management definitions in a summary sent to all 20 original panelists for review and comments.

Development of a Tool for Use by Healthcare Organizations

A project objective was to promote development of improvement agendas27 by executive, middle, and frontline managers. To achieve this objective, the project team developed two ready-to-use tools based on final panel results.

RESULTS

Stakeholder Panelist Participation

Panelists were primarily associated with VHA, but included one from Canada, one from Kaiser Permanente, and a senior adviser to the US Government Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services who is also affiliated with the VHA. Panelists represented all pre-identified target 7-P groups and areas of expertise, including two patients.

All panelists (N = 20) completed the pre-panel survey. The in-person panel was attended by 19 panelists. Responses from 17 panelists were available for the post-panel survey analysis (response rate 85%). All 14 panelists who agreed to work with the study team to develop recommendations and implementation suggestions, including the two patient representatives, completed participation in at least one of the 2 planned calls. All 20 panelists received final study products for review and comments.

Panel Consensus on definitions of Access Management

Analysis of access management definitions discussions showed recurrent themes across subpanels. These were timeliness, ease of access, actual versus perceived needs, and importance of the patient perception of access.28, 30 Panel members indicated that their final definitions, shown in Table 3, should be viewed as broad guides.

Panel Consensus on Priorities for Action

The post-panel survey established eight items as key priorities for action that were both important and urgent (Table 4). Among the eight priorities, panelists identified two key organizational structure targets, four process improvement targets, and two outcome targets.

The panel endorsement of the eight priorities ranged from 53% of panelists (optimizing provider visit schedules; provider and staff morale related to access mismatch) to 100% endorsement (patient telephone access management) (see Table 5). Many dropped items were identified as important but not urgent, such as wait times, use of a variety of non-face to face modalities other than telephone, and evaluation of patient “walk-in” visits. Panelists viewed these as contributing factors, rather than as fundamental priorities.

Panel Consensus on Recommendations and Implementation Suggestions

The project team identified 25 potential recommendations, or 2 to 9 per priority area, based on literature review and panel discussions. The total number of recommendations dropped to 14 as panelists came to consensus on those that were most important, and others that could be eliminated because they were duplicative or low impact.

Final User-Ready Tool for Developing an Access Management Improvement Agenda

For preparing a final tool, panelists directed the team to indicate at what level of an organization endorsement for initiating the recommendations would be required. They also endorsed listing key references for recommendations. Online Appendix 1 includes the final set of key priorities, recommendations for achieving them, and suggestions for implementation, as revised and reviewed by panelists. Online Appendix 2 includes additional introductory material on how to use the tool to develop an access improvement agenda in a “slidedoc”39 format (i.e., slides meant to be read, not presented). For example, health systems should consider which key priorities have already been achieved as part of agenda development. A PowerPoint© slidedoc version with additional embedded material is available from the authors.

DISCUSSION

While access to healthcare has always been of paramount importance, responsibility for ensuring access has often been dispersed across many organizations, leaving none accountable overall. Integrated healthcare organizations such as the VHA and others, however, have both responsibility for enabling access to needed care of all types and population-based data for monitoring it. These circumstances make access challenges more visible and create opportunities for improvement. We initiated a formal systematic review of prior literature and a qualitative study of the experiences of VHA access managers to identify factors influencing access. We then engaged a broadly representative, evidence-informed stakeholder panel in a modified Delphi panel process to identify priorities for action based on their ratings of over 80 of these factors. The resulting eight priorities focus on structure, processes, and outcomes and address essential organizational access management targets. These priorities provide valid current guidance on access management improvement for healthcare organization managers and leaders.

Learning organizations aim to use evidence as the basis for improvement, yet decades of research on access provide limited assistance to healthcare organization leaders and managers as they confront ongoing access challenges.40 The inevitability of continuous local and organizational changes in supply and demand, and of the need to integrate patient, provider team, and organizational considerations and preferences, precludes a one-size-fits-all approach. We therefore sought to develop a basis for improvement rather than a set of mandates, and to focus on North American integrated healthcare systems as our context. We think aspects of our work, however, can serve as a foundation for similar initiatives within other organizational contexts, such as practice networks or community-based improvement efforts,

Our systematic review found no studies addressing access as a “wicked” management and policy problem that must be addressed across organizational programs and boundaries.7 Most access management improvement interventions in our review focused only on the open access approach.5 Open or advanced access focuses on how to manage primary care visit schedules so that a patient is offered a prompt appointment whatever the reason for the visit request.21 Existing studies show that system improvement based on single access elements (such as open access21) is not only insufficient, but can result in negative consequences. Panelists viewed open access principles as methods for achieving the more fundamental priorities of better group practice management, care coordination, proactive demand management, and patient and provider experience (see recommendations, suggestions, and references for priorities 2, 4, and 6 in Online Appendix 1 focusing on open access) rather than as priority goals in themselves. Within this more comprehensive context, health systems could enlist open access24, 41, 42 alongside other relevant approaches as part of an overall access management improvement agenda.

Developing an agreed-upon implementation agenda, spanning organizational boundaries and taking account of local resources, have been shown to be associated with quality improvement initiative success.27 The approach described here incorporates each of these features. Our access management tools (Online Appendices 1 and 2) provide concrete guidance on shaping agenda development and provide (Online Appendix 2) an approach for integrating research evidence, local data, and relevant stakeholder input. The priorities themselves span both professions (e.g., nurse, physician, administration) and organizational units (e.g., call centers, information technology, contracting).

In the last decade, many healthcare organizations have changed their access management policies;43 most of these changes, however, have not been rigorously evaluated.5, 17, 18 Modified Delphi expert panel methods that take account of existing knowledge, while supplementing it with consensus across diverse perspectives, can provide valuable guidance for bridging gaps in research-based knowledge.2, 3, 34 A future study testing the effectiveness of achieving adequate performance across all eight priorities identified here, however, would be valuable.

All eight top priorities resulting from the panel met our criterion of endorsement by more than half of the panelists as both important and urgent. The exact level of agreement, however, varied. Interestingly, the most agreed-upon priority (100% agreement) was one that receives scant mention in access literature—i.e., the need for “routine evaluation of the degree to which patient telephone calls are (a) answered promptly and (b) routed accurately and appropriately, as judged in terms of patients’ clinical needs and preferences.” The high level of panelist agreement in the absence of available research strongly suggests a need for additional investigation.

As structure improvement targets, the panel identified interdisciplinary leadership at the local practice site level, with shared governance across physician, nurse, and administrative lines, and achievement of a clear group practice management structure originating at an executive level as top priorities. These targets reflected approaches for achieving the level of boundary spanning communication and decision-making across disciplines and programs required for optimal access management.

As process improvement targets, the panel identified two little-studied influences on access (high-quality telephone access, contingency staffing) and two more commonly referenced in open access and other literature (care coordination and optimizing provider visit schedules).

All panelists, with strong endorsement from the two patient representatives, saw telephone access as fundamental for ensuring appropriate patient safety, scheduling, and coordination.33 While virtual or computer access is increasingly important (see priority 7, and suggestions related to priorities 3, 5, 7, and 8, Online Appendix 1), and can reduce patient and provider telephone burden, patient computer abilities and access vary, as do the abilities of provider teams to respond promptly to computer messages. For these and other reasons, computers cannot eliminate the need for high-quality telephone access. Yet healthcare literature provides sparse guidance on how primary care practices should structure or evaluate telephone services. Similarly, panelists identified contingency staffing as critical but often overlooked. They noted that without contingency staffing availability, delivery systems would either fail to deliver adequate access or would be continuously (and likely unsustainably) overstaffed.

In terms of outcomes, panelists viewed both patient and provider experiences of access as critical and intertwined. Because patient experiences of access can reflect all access modalities (e.g., telephone, online, and in-person), panelists judged improving patient experience to be the best overall outcome target for access improvement.

A theme among the panel priorities was the importance of nurse role development both as organizational leaders and as clinical care team leaders. Achievement of optimal nursing roles, as shown in panel recommendations (Online Appendix 1), will require training and role development.

We aimed to provide guidance to health systems, rather than individual primary care practices. However, we expect that, although the relative urgency and importance of the priorities may differ for smaller or unaffiliated practices, all eight priorities are potentially relevant even at the individual practice level. Smaller systems or practices could also consult the overall framework we provide (Table 2) or the survey based on it.30

Our study had limitations. While our stakeholders were diverse in professional backgrounds, they represented only large managed care systems in North America. More than half of the panelists had VHA backgrounds. During panel discussions, however, non-VHA panelists re-iterated the extent to which priorities were common across delivery systems, differing mostly in the extent to which a priority was currently problematic or had already been adequately achieved. Additionally, our panel was designed to include only 20 participants. This size is maximal for an in-person modified Delphi panel. A future online larger panel may be helpful for addressing other contexts.37 As another limitation, we did not achieve (and did not aim to achieve) full agreement among panelists; we followed strict procedures to identify rather than coerce consensus. However, disagreements on priorities were largely limited to whether a priority was both urgent and important, or simply important, and all participating panelists endorsed our final definitions, priorities, recommendations, and suggestions. We also did not assess the costs or methods for paying for enhanced access. Finally, our results are intended to be formative rather than definitive.

Our findings imply that the current healthcare organization focus on timeliness of access and on achieving open access goals is too narrow to succeed. Because it is often the factor upon which achievement of all others may depend, we recommend establishing cross-cutting access management (see structure-related priorities) as a starting point. We then recommend a formal process of assessing current accomplishments in each priority area and engaging stakeholders in addressing one or two (Online Appendix 2).

In summary, this study provides a valid foundation for action for achieving optimal access management within healthcare organizations, as well as providing a basis for future research. Our final eight key priorities are concise action points and are linked to relevant evidence and guidance on implementation in ready-to-use tools (Appendices 1 and 2). Our work as reported here can provide healthcare organization leaders and managers, particularly those in integrated healthcare organizations, with a foundation for undertaking access management improvement, while tailoring it to their own contexts.

References

Kirschner K, Braspenning J, Maassen I, Bonte A, Burgers J, Grol R. Improving access to primary care: the impact of a quality-improvement strategy. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19(3):248-251.

Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall M. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11(4):358-364.

Baker J, Lovell K, Harris N. How expert are the experts? An exploration of the concept of 'expert' within Delphi panel techniques. Nurs Res 2006;14(1):59-70.

Rubenstein LV, Fink A, Yano EM, Simon B, Chernof B, Robbins AS. Increasing the impact of quality improvement on health: an expert panel method for setting institutional priorities. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 1995;21(8):420-432.

Miake-Lye IM, Mak S, Shanman R, Beroes JM, Shekelle PG. Access Management Improvement: A Systematic Review. VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports. 2017.

Rubenstein LV, Sayre G, LeRouge C. Clinical Practice Management Model Evaluation-Qualitative Evaluation: Final Report. November 8, 2016.

Rittel HWJ, Webber MM. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Plannng. Policy Sci 1973;4:155-169.

Braithwaite J, Churruca K, Ellis LA, et al. Complexity Science in Healthcare – Aspirations, Approaches, Applications and Accomplishments: A White Paper. Sydney, Australia: Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Macquarie University;2017.

Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743-1748.

Bhat VN. Institutional arrangements and efficiency of health care delivery systems. Eur J Health Econ 2005;6(3):215-222.

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC)2001. 0309072808.

Institute of Medicine. Transforming Health Care Scheduling and Access: Getting to Now. Washington (DC)2015.

Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care 1981;19(2):127-140.

Salisbury C, Goodall S, Montgomery AA, et al. Does Advanced Access improve access to primary health care? Questionnaire survey of patients. Brit J Gen Pract 2007;57(541):615-621.

Parchman ML, Noel PH, Lee S. Primary care attributes, health care system hassles, and chronic illness. Med Care 2005;43(11):1123-1129.

Shippee ND, Shah ND, May CR, Mair FS, Montori VM. Cumulative complexity: a functional, patient-centered model of patient complexity can improve research and practice. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65(10):1041-1051.

Rose K, Ross JS, Horwitz LI. Advanced access scheduling outcomes: A systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2011;171(13):1150-1159.

VanDeusen Lukas C, Meterko M, Mohr D, Nealon Seibert M. The Implementation and Effectiveness of Advanced Clinic Access. Washington, DC: HSR&D Management Decision and Research Center; Office of Research and Development; Department of Veterans Affairs; June 2004.

Hargraves JL. Survey of Health Care Experiences of Patients (SHEP) Methods Overview and Technical Summary. In: OoQaP DoVA, ed2009:1-22.

Hargraves JL, Hays RD, Cleary PD. Psychometric properties of the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (CAHPS) 2.0 adult core survey. Health Services Research & Development Service;2003.

Mehrotra A, Keehl-Markowitz L, Ayanian JZ. Implementation of Open Access Scheduling in Primary Care: A Cautionary Tale. Ann Intern Med 2008;148(12):915-922.

Phan K, Brown SR. Decreased continuity in a residency clinic: a consequence of open access scheduling. Fam Med 2009;41(1):46-50.

Salisbury C, Montgomery AA, Simons L, et al. Impact of Advanced Access on access, workload, and continuity: controlled before-and-after and simulated-patient study. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57(541):608-614.

Bodenheimer T. Improving Access to Primary Care. Med Care 2018;56(10):815-817.

Kiran T, O'Brien P. Challenge of same-day access in primary care. Can Fam Physician 2015;61(5):399-400, 407-399.

Rosen R. Meeting need or fuelling demand? Improved access to primary care and supply-induced demand. United Kingdom: Nuffield Trust; June 2014.

Clack L, Zingg W, Saint S, et al. Implementing infection prevention practices across European hospitals: an in-depth qualitative assessment. BMJ Qual Saf 2018;27(10):771-780.

Hempel S, Hilton L, Stockdale S, et al. Defining Access Management in Healthcare Delivery Organizations. Under review. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.16934/v1.

Kaboli PJ, Miake-Lye IM, Ruser C, et al. Sequelae of an Evidence-based Approach to Management for Access to Care in the Veterans Health Administration. Med Care. 2019;57 Suppl 10 Suppl 3:S213-S220.

Hempel S, Stockdale S, Danz M, et al. Access Management in Primary Care: Perspectives from an Expert Panel. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Coporation; 2018.

Hussey PS, Ringel JS, Ahluwalia S, et al. Resources and Capabilities of the Department of Veterans Affairs to Provide Timely and Accessible Care to Veterans. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation;2015.

Farmer CM, Hosek SD, Adamson DM. Balancing Demand and Supply for Veterans' Health Care: A Summary of Three RAND Assessments Conducted Under the Veterans Choice Act. Rand Health Quart 2016;6(1):12.

Buell RW, Huckman RS, Travers S. Improving Access at VA. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School; November 2016.

Concannon TW, Meissner P, Grunbaum JA, et al. A new taxonomy for stakeholder engagement in patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27(8):985-991.

Rubenstein LV, Kahn KL, Reinisch EJ, et al. Changes in quality of care for five diseases measured by implicit review, 1981 to 1986. JAMA. 1990;264(15):1974-1979.

Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311(7001):376-380.

Khodyakov D, Hempel S, Rubenstein L, et al. Conducting online expert panels: a feasibility and experimental replicability study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:174.

Fortney JC, Burgess JF, Jr., Bosworth HB, Booth BM, Kaboli PJ. A re-conceptualization of access for 21st century healthcare. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26 Suppl 2:639-647.

Fisher CD. Slidedocs: Spread Ideas With Effective Visual Documents, by Nancy Duarte. Acad Manag Learn Educ. 2017;16((2)):339-342.

Knight AW, Caesar C, Ford D, Coughlin A, Frick C. Improving primary care in Australia through the Australian Primary Care Collaboratives Program: a quality improvement report. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21(11):948-955.

Murray M, Berwick DM. Advanced access: reducing waiting and delays in primary care. JAMA. 2003;289(8):1035-1040.

Cameron S, Sadler L, Lawson B. Adoption of open-access scheduling in an academic family practice. Can Fam Physician 2010;56:906-911.

Committee on Optimizing Scheduling in Health Care. Transforming Health Care Scheduling and Access - Getting to Now. Washington, D. C.: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies;2015.

Acknowledgments

We thank our distinguished panel of experts: David Aron, MD; Paul Brynen; M. Scott Ballard; Carolyn Clancy, MD; Joan Clifford, DNP, RN; Angela Denietolis, MD; Steve Fihn, MD; Clinton (Leo) Greenstone, MD; Karey Johnson, DNP, RN; Peter Kaboli, MD; Tara Kiran, MD; Thomas Klobucar, PhD; Jia Li; Storm Morgan MSN, RN, MBA; Michael Eugene Morris, MD; Greg Orshansky, MD; Ashok Reddy, MD; Bob Rubin; Christopher Ruser, MD; Ali Sonel, MD.

In addition, we thank our guests at the expert panel meeting: Lisa Altman MD, Tim Dresselhaus MD, David Ganz MD PhD, Desiree Hill, Isomi Miake-Lye PhD, Brian Mittman PhD, Karin Nelson MD MSHS, John Ovretveit PhD, George Sayre MD PhD, Paul Shekelle MD MPH PhD, Kathrine Williams, Elisabeth Yano PhD MSPH, and Jean Yoon PhD, for critical contributions.

We thank Yee-Wei Lim PhD for content expertise; Thomas Concannon PhD, David Grembowski PhD, Rebecca Anhang Price, and Paul Koegel PhD for content review; Marika Booth for statistical analyses; Lara Hilton PhD MPH for qualitative analyses; Emily Ashmore for tool preparation; Alaina Mori and Aneesa Motala for project assistance; Patty Smith for administrative assistance; and Claudia Rodriguez for assistance preparing report material.

Funding

The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and the findings and conclusions do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

The study was assessed by the RAND Human Subjects Protection Committee, found to be of minimal risk, and determined to be exempt on October 5, 2016, ID2016-0610; reassessed November 16, 2017, ID2017-0911).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations:

1. Kirsh S. April 13, 2018. Access Management Priorities in Primary Care. Poster presentation at the American College of Medical Quality Annual Meeting, April 13, 2018.

2. Hempel S, Miake-Lye IM, Kirsh S, Morris M, Rubenstein LV. Managing Primary Care Access in Healthcare Systems: A Complex Challenge. Panel Presentation at the AcademyHealth 2018 Annual Research Meeting.

3. Kirsh S, Miake-Lye IM, Morris M, Rubenstein LV. Managing Primary Care Access in Healthcare Systems: A Complex Challenge. VA Health Services Research and Development Cyberseminar. Oct 18, 2018.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rubenstein, L., Hempel, S., Danz, M. et al. Eight Priorities for Improving Primary Care Access Management in Healthcare Organizations: Results of a Modified Delphi Stakeholder Panel. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 523–530 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05541-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05541-2