ABSTRACT

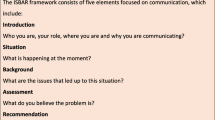

BACKGROUND

Although direct patient care is necessary for experiential learning during residency, inpatient perceptions of the roles of resident and attending physicians in their care may have changed with residency duty hours.

OBJECTIVE

We aimed to assess if patients’ perceptions of who is most involved in their care changed with residency duty hours.

DESIGN

This was a prospective observational study over 12 years at a single institution.

PARTICIPANTS

Participants were 22,408 inpatients admitted to the general medicine teaching service from 2001 to 2013, who completed a 1-month follow-up phone interview.

MAIN MEASURES

Percentage of inpatients who reported an attending, resident, or intern as most involved in their care by duty hour period (pre-2003, post-2003–pre-2011, post-2011).

KEY RESULTS

With successive duty hour limits, the percentage of patients who reported the attending as most involved in their care increased (pre-2003 20 %, post-2003–pre-2011 29 %, post-2011 37 %, p < 0.001). Simultaneously, fewer patients reported a housestaff physician (resident or intern) as most involved in their care (pre-2003 20 %, post-2003–pre-2011 17 %, post-2011 12 %, p < 0.001). In multinomial regression models controlling for patient age, race, gender and hospitalist as teaching attending, the relative risk ratio of naming the resident versus the attending was higher in the pre-2003 period (1.44, 95 % CI 1.28-1.62, p < 0.001) than the post-2003–pre-2011 (reference group). In contrast, the relative risk ratio for naming the resident versus the attending was lower in the post-2011 period (0.79, 95 % CI 0.68-0.93, p = 0.004) compared to the reference group.

CONCLUSIONS

After successive residency duty hours limits, hospitalized patients were more likely to report the attending physician and less likely to report the resident or intern as most involved in their hospital care. Given the importance of experiential learning to the formation of clinical judgment for independent practice, further study on the implications of these trends for resident education and patient safety is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Residency training was founded on the concept of experiential learning, whereby residents become proficient in clinical care through directly caring for patients. Traditionally, interns, or first-year residents, were most responsible for direct patient care, with appropriate supervision from senior residents and attending physicians.

Resident duty hour restrictions in 2003 and in 2011 have been controversial due to the negative impact on resident education and professional development.1 While studies have shown little to no changes in patient outcomes, concerns continue to be raised regarding the tradeoffs between improved resident fatigue and the effects of duty hours on clinical experience.2 Reduced resident work hours have led to increased handoffs, concerns over decreased professional responsibility towards patients, and less time in direct patient care.3,4 Supervising attendings also report a greater role in direct patient care, which could lead to attending burnout, fatigue, and less time for teaching.5,6

While the impact of duty hour restrictions on patient outcomes has been extensively examined, few studies examine patient perspectives.7,8 Given calls for a more patient-centered healthcare system, it is important to examine how inpatients perceive roles of medical trainees in their care with successive duty hour restrictions. This study aims to characterize whom hospitalized patients perceive as most involved in their care, and to determine how this perception has changed with successive resident duty hour limitations in 2003 and 2011.

METHODS

Design

From 1 July 2001 through 30 June 2013, all University of Chicago general medicine inpatients were approached to enroll in an ongoing research study that was initially created to assess the impact of hospitalists on patient outcomes, but now serves as core infrastructure to answer questions related to hospital care.9,10 Patients who consented were interviewed at admission to collect basic health information. During a 30-day follow-up phone interview, patients were asked, “During your inpatient hospital stay, who was most involved in your medical care?” Response options included, “Attending”, “Resident”, “Intern”, “Medical Student”, “Nurse”, “I don’t know”, “Other”. Patient charts were reviewed to obtain basic demographics (age, gender, race, and length of stay), and the identity of the ward attending, who was categorized as hospitalist or non-hospitalist. Patients admitted to non-teaching services were excluded.

Structure of General Medicine Teaching Teams

Teams included one teaching attending (academic hospitalist, generalist, or subspecialist) who supervised a second or third year medicine resident, two medicine interns (categorical or preliminary), and one to two medical students. Attendings worked in 1-month or 2-week blocks without a day off. Housestaff had one day off weekly, averaged over their month-long rotation. Pre-2003, there was no restriction on residency duty hours and resident teams took overnight calls every fourth night, admitting patients and cross-covering for other teams. During 2003 to 2011, teams were expected to be compliant with the 2003 duty hour rules, including an 80-hour work-week maximum and no more than 30 hours of consecutive duty. Because of high rates of noncompliance between 2003 and 2005, in 2006, a “day float” resident was added to care for the post-call team’s patients so they could sign out after 30 hours of duty.11 In 2011, to comply with the 16-hour maximum duty period for interns, supervising residents worked 28 hours consecutively and supervised two interns who worked every fourth on-call day in two shifts: (1) ‘day intern’ admitted from 7 am to 9 pm; and (2) ‘night intern’ admitted at 8 pm and attended morning attending rounds until 11 am post-call. The resident day float now provided support to the team on on-call and post-call days.

During the study, white boards in patient rooms were routinely updated with nurses’ names. Between the academic years ending in 2007–2009, physicians on teaching teams were coached to use picture cards to identify themselves to patients.12 While this initiative improved patient ability to name their doctors, fewer patients understood team member roles.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data. Data was grouped into three time periods based on resident duty hours by academic year from July to June (pre-2003, post-2003–pre-2011, and post-2011). Patient responders to the follow-up survey were compared to non-responders (age, race, gender).

Chi squared tests were used to determine the association between duty hour period and whom patients identified as most involved in their care. In addition, multinomial logistic regression, controlling for patient factors, and whether the teaching attending was a hospitalist, was used to determine relative risk ratio of naming a specific category versus the attending during the time periods. We also examined how patients’ responses changed by year to ascertain secular trends.

RESULTS

From 1 July 2001 through 30 June 2013, 39,469 patients were admitted to the University of Chicago general medicine teaching service. Of these patients, 22,750 (58 %) completed the follow-up interview. Most (63 %) were female and African-American (78 %), reflecting our patient population. While responders were less likely to be African-American, female, or younger in age compared to non-responders, these differences were small (African-American responder 79 % vs. 81 % non-responder, p < 0.001; female responder 63 % vs. female non-responder 59 %, p < 0.001, age difference responders −0.49 years (95 % CI -0.90 to -0.09, p = 0.02). (Table 1).

The most common response to who was most involved in patients’ care was “I don’t know” (29 %), followed by the “attending” (28 %) as a close second and “other” (26 %) as third. Seventeen percent of patients reported that a housestaff member was most involved in their care (11 % “resident”, 6 % “intern”). The percentage of patients reporting their attending as most involved in their care rose with successive duty hour restrictions, from 20 % pre-2003 to 29 % 2003–2011, to 37 % post-2011 [Pearson chi2(2) = 275.5, p < 0.001]. Simultaneously, fewer patients listed any housestaff (intern or resident) in each period, with 20 % pre-2003, 17 % 2003–2011, and 13 % post-2011 [Pearson chi2(2) = 34.5, p < 0.001] (Fig. 1). Also, fewer patients reported the intern as most involved in their care with duty hour restrictions (9 % pre-2003, 6 % 2003–2011, 3 % post-2011 [Pearson chi2(2) = 101.8, p < 0.001]. Lastly, fewer patients responded “I don’t know” after the 2011 duty hours period (32 % pre-2001, 30 % 2001–2011, and 22 % post-2011 [Pearson chi2(2) = 80.9, p < 0.001].

These patterns remained significant in a multinomial regression model controlling for patient demographics and whether the attending was a hospitalist. Compared to the post-2003–pre-2011 period, patients admitted pre-2003 were more likely to name the resident versus the attending (RRR 1.44, 95 % CI 1.28-1.62, p < 0.001). In contrast, the relative risk ratio for naming the resident versus the attending after 2011 was lower than the post-2003–pre-2011 period (RRR 0.79, 95 % CI 0.68–0.93, p = 0.004). This relationship was also demonstrated for naming “intern” vs. attending, with even greater effect sizes.

When examining percentage of patients reporting the attending as most involved in their care by year, the post-2003–pre-2011 period includes a sharp increase in the academic year ending 2006, which roughly corresponded to the new day float system to achieve better compliance with the 2003 duty hours. Additionally, in the year preceding the 2011 duty hours, the percentage of patients reporting the attending as most involved increased. This corresponds to piloting service changes in anticipation of the 2011 duty hour rules (Fig. 2).

Percentage of patients who identified attending as most involved with their care by year (n = 22,750). The figure shows that the fraction of patients who answered the attending was most involved in their hospital care. In the 2 years after implementation of 2003 duty hours in the academic year ending in 2006, noncompliance with duty hours was higher until services were restructured in the academic year ending in 2006 to include a day float resident. In the academic year ending in 2011 that preceded implementation of July 2011 duty hours, service structures were phased in early in anticipation of the 2011 duty hours.

DISCUSSION

In this study, successive resident duty hour restrictions were associated with a doubling of the percentage of patients reporting the attending physician as most involved in their care. Simultaneously, the percentage of patients identifying a housestaff as most involved in their care decreased. Lastly, roughly one-third of patients did not know who was most involved in their care, underscoring the need for interventions to improve patient understanding of their medical care teams.

It is not surprising that more patients reported the attending physician as most involved in their care with duty hour limitations. While attending physicians report increased workloads from reduced availability of residents with duty hours,13 other reasons could explain this trend. Attendings work 14 consecutive days, while residents have 1 day off weekly. Patients may perceive the doctor they see daily as most involved.

Moreover, an increased focus on direct supervision by the ACGME could result in attendings proactively introducing themselves to patients and taking a larger role in direct care.14 Simultaneously, demands of documentation and care coordination have increased, pulling residents, especially interns, away from the bedside. Electronic health records and the resulting “iPatient” phenomenon have heralded an era where residents spend more time with computers than with patients.15 Our institution implemented electronic order entry in 2009, electronic physician documentation in 2010, and distributed Apple (Cupertino, CA) iPads to medicine residents in 2012, all of which could decrease housestaff time with patients.16 Future education for trainees on how to use technology, such as the electronic health record, in a patient-centered way is warranted.

Regardless of the reason, these findings have implications for residency training. If residents and interns are truly less involved in patient care, duty hours may prevent clinical experiences necessary to attain competence. The move to the Next Accreditation System, with a focus on direct observation to document achievement of milestones, is one step towards ensuring competence despite shorter hours. Lengthening residency training is another alternative, albeit less popular. Even if actual clinical experiences of residents changed minimally after duty hours, changes in patient perceptions of who is involved in their care have ramifications. If housestaff feel they are not most directly responsible for the care of the patient, housetaff and patients may defer to the attending, threatening critical clinical decision-making skills and autonomy required for independent practice.17

This study has several limitations. It was performed at a single site, limiting generalizability. Phone interviews were conducted in English, limiting our applicability to patients of limited English proficiency. We cannot infer causality due to the observational design. Other secular trends may explain these results. The landmark Institute of Medicine Reports that launched the patient safety movement could have made attending physicians more proactive, or empowered patients to ask questions about their team members’ roles.18,19 While our study focuses on patient perceptions of their care, patients may not know the roles of their physician team members or recall who was most involved in their care 1 month after discharge. In 2006, an item on the patient survey explored the understanding of roles of physician team members. Although not present during the entire study, over 80 % of patients reported at least a “Good” understanding of the roles of physician team members. Nevertheless, we did not ascertain if these perceptions translated into an actual understanding of the roles and inpatients do face difficulty identifying their treating physician’s name and role.20

CONCLUSION

With successive implementation of resident duty hour restrictions, hospitalized patients are more likely to report the attending and less likely to report the resident or intern as most involved in their care. These changes could be due to reduced resident hours, greater attending involvement in patient care, or less resident time with patients because of electronic health records. Given the importance of experiential learning to residents’ progression to clinical independence, it is critical to examine the implications of these findings on resident education.

REFERENCES

Weinstein DF, Arora V, Drolet B, et al. Residency training—a decade of duty-hours regulations. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(24):e32.

Shea JA, Willett LL, Borman KR, et al. Anticipated consequences of the 2011 duty hours standards: views of internal medicine and surgery program directors. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):895–903.

Arora VM, Farnan JM, Humphrey HJ. Professionalism in the era of duty hours: time for a shift change? JAMA. 2012;308(21):2195–2196.

Block L, Habicht R, Wu AW, et al. In the wake of the 2003 and 2011 duty hours regulations, how do internal medicine interns spend their time? J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(8):1042–1047.

Reed DA, Levine RB, Miller RG, et al. Effect of residency duty-hour limits: views of key clinical faculty. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(14):1487–1492.

Roshetsky LM, Coltri A, Flores A, Vekhter B, Humphrey HJ, Meltzer DO, Arora VM. No time for teaching? Inpatient attending physicians’ workload and teaching before and after the implementation of the 2003 duty hours regulations. Acad Med. 2013;88(9):1293–1298.

Fletcher KE, Wiest FC, Halasyamani L, et al. How do hospitalized patients feel about resident work hours, fatigue, and discontinuity of care? J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):623–628.

Blum AB, Raiszadeh F, Shea S, et al. US public opinion regarding proposed limits on resident physician work hours. BMC Med. 2010;8:33.

Meltzer D, Manning WG, Morrison J, et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866–874.

Arora VM, Fish M, Basu A, Olson J, Plein C, Suresh K, Sachs G, Meltzer DO. Relationship between quality of care of hospitalized vulnerable elders and postdischarge mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(9):1642–1648.

Arora VM, Georgitis E, Siddique J, et al. Association of workload of on-call medical interns with on-call sleep duration, shift duration, and participation in educational activities. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1146–1153.

Arora VM, Schaninger C, D’Arcy M, Johnson JK, Humphrey HJ, Woodruff JN, Meltzer DO. Improving inpatients’ identification of their doctors: use of FACE cards. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35(12):613–619.

Arora V, Meltzer D. Effect of ACGME duty hours on attending physician teaching and satisfaction. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(11):1226–1228.

Nasca TJ, Day SH, Amis ES Jr. ACGME Duty Hour Task Force. The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME Task Force. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(2):e3.

Verghese A. Culture shock—patient as icon, icon as patient. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(26):2748–2751.

Patel BK, Chapman CG, Luo N, et al. Impact of mobile tablet computers on internal medicine resident efficiency. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):436–438.

Farnan JM, Johnson JK, Meltzer DO, Humphrey HJ, Arora VM. On-call supervision and resident autonomy: from micromanager to absentee attending. Am J Med. 2009;122(8):784–788.

Leape LL, Berwick DM. Five years after To Err Is Human: what have we learned? JAMA. 2005;293(19):2384–2390.

Berwick DM. A user’s manual for the IOM’s ‘Quality Chasm’ report. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(3):80–90.

Arora V, Gangireddy S, Mehrotra A, et al. Ability of hospitalized patients to identify their in-hospital physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(2):199–201.

Acknowledgements

Contributors

Arora: conception and design, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, obtaining funding, administrative, technical, or material support, supervision.

Prochaska: acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, administrative, technical, or material support.

Farnan: conception and design, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Meltzer: conception and design, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual, obtaining funding, administrative, technical, or material support, supervision.

Funders

This study has been funded by AHRQ R01-HS10597 Multicenter Trial Hospitalists, NIGMS R01 GM075292 TEACH Research, and AHRQ U18 HS016967 CERT Hospital Med & Economics. Funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Dr. Arora had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Prior Presentations

Previous presentations include a plenary presentation at the annual Society of General Internal Medicine Meeting in San Diego in April 2014, and a poster presentation at the Society of Hospital Medicine in Las Vegas in March 2014.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00204048 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00204048

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arora, V.M., Prochaska, M.T., Farnan, J.M. et al. Patient Perceptions of Whom is Most Involved in Their Care with Successive Duty Hour Limits. J GEN INTERN MED 30, 1275–1278 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3239-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3239-0