Abstract

Introduction

The impact of neoadjuvant therapy on postpancreatectomy complications is inadequately described.

Methods

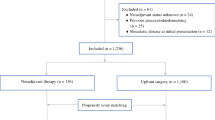

Data from the NSQIP Pancreatectomy Demonstration Project (11/2011 to 12/2012) was used to identify patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma who did and did not receive neoadjuvant therapy. Neoadjuvant therapy was classified as chemotherapy alone or radiation ± chemotherapy. Outcomes in the neoadjuvant vs. surgery first groups were compared.

Results

Of 1,562 patients identified at 43 hospitals, 199 (12.7 %) received neoadjuvant therapy (99 chemotherapy alone and 100 radiation ± chemotherapy). Preoperative biliary stenting (57.9 vs. 44.7 %, p = 0.0005), vascular resection (41.5 vs. 17.3 %, p < 0.0001), and open resections (94.0 vs. 91.4 %, p = 0.008) were more common in the neoadjuvant group. Thirty-day mortality (2.0 vs. 1.5 %, p = 0.56) and postoperative morbidity rates (56.3 vs. 52.8 %, p = 0.35) were similar between groups. Neoadjuvant therapy patients had fewer organ space infections (3.0 vs. 10.3 %, p = 0.001), and neoadjuvant radiation patients had fewer pancreatic fistulas (7.3 vs. 15.4 %, p = 0.03).

Conclusions

Despite evidence for more extensive disease, patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy did not experience more complications. Neoadjuvant radiation was associated with lower pancreatic fistula rates. These data provide evidence against higher postoperative complication rates in patients with pancreatic cancer who are treated with neoadjuvant therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Tempero, MA, Arnoletti, JP, Behrman, SW, et al. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, version 2.2012: featured updates to the NCCN Guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10: 703-713.

Parmar AD, VG, Tamirisa NP, Sheffield KM, Riall TS. Trajectory of Care and Use of Multimodality Therapy in Locoregional Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Surgery.2014;156:280-9.

Weese, JL, Nussbaum, ML, Paul, AR, et al. Increased resectability of locally advanced pancreatic and periampullary carcinoma with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Int J Pancreatol. 1990;7: 177-185.

Jessup, JM, Steele, G, Jr., Mayer, RJ, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy for unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Arch Surg. 1993;128: 559-564.

Yeung, RS, Weese, JL, Hoffman, JP, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation in pancreatic and duodenal carcinoma. A Phase II Study. Cancer. 1993;72: 2124-2133.

Evans, DB, Varadhachary, GR, Crane, CH, et al. Preoperative gemcitabine-based chemoradiation for patients with resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26: 3496-3502.

Varadhachary, GR, Wolff, RA, Crane, CH, et al. Preoperative gemcitabine and cisplatin followed by gemcitabine-based chemoradiation for resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26: 3487-3495.

Cetin, V, Piperdi, B, Bathini, V, et al. A Phase II Trial of Cetuximab, Gemcitabine, 5-Fluorouracil, and Radiation Therapy in Locally Advanced Nonmetastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2013;6: S2-9.

Lee, JL, Kim, SC, Kim, JH, et al. Prospective efficacy and safety study of neoadjuvant gemcitabine with capecitabine combination chemotherapy for borderline-resectable or unresectable locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Surgery. 2012;152: 851-862.

Landry, J, Catalano, PJ, Staley, C, et al. Randomized phase II study of gemcitabine plus radiotherapy versus gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil, and cisplatin followed by radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil for patients with locally advanced, potentially resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101: 587-592.

Pitt, HA, Kilbane, M, Strasberg, SM, et al. ACS-NSQIP has the potential to create an HPB-NSQIP option. HPB (Oxford). 2009;11: 405-413.

Parikh, P, Shiloach, M, Cohen, ME, et al. Pancreatectomy risk calculator: an ACS-NSQIP resource. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12: 488-497.

Parmar, AD, Sheffield, KM, Vargas, GM, et al. Factors associated with delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford). 2013;15: 763-772.

User Guide for the 2010 Participant Use Data File. [American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program]. Available from URL: http://site.acsnsqip.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/ACS-NSQIP-Participant-User-Data-File-User-Guide_06.pdf. [accessed January, 2013.

Fang, Y, Gurusamy, KS, Wang, Q, et al. Pre-operative biliary drainage for obstructive jaundice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9: CD005444.

Sewnath, ME, Karsten, TM, Prins, MH, et al. A meta-analysis on the efficacy of preoperative biliary drainage for tumors causing obstructive jaundice. Ann Surg. 2002;236: 17-27.

van der Gaag, NA, Rauws, EA, van Eijck, CH, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage for cancer of the head of the pancreas. N Engl J Med. 2010;362: 129-137.

Araujo, RL, Gaujoux, S, Huguet, F, et al. Does pre-operative chemoradiation for initially unresectable or borderline resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma increase post-operative morbidity? A case-matched analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2013;15: 574-580.

Pecorelli, N, Braga, M, Doglioni, C, et al. Preoperative chemotherapy does not adversely affect pancreatic structure and short-term outcome after pancreatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17: 488-493.

Laurence, JM, Tran, PD, Morarji, K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of survival and surgical outcomes following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15: 2059-2069.

Takahashi, H, Ogawa, H, Ohigashi, H, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation reduces the risk of pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Surgery. 2011;150: 547-556.

Birkmeyer, JD, Dimick, JB. Potential benefits of the new Leapfrog standards: effect of process and outcomes measures. Surgery. 2004;135: 569-575.

Allareddy, V, Ward, MM, Allareddy, V, Konety, BR. Effect of meeting Leapfrog volume thresholds on complication rates following complex surgical procedures. Ann Surg. 2010;251: 377-383.

Roberts, KJ, Storey, R, Hodson, J, et al. Pre-operative prediction of pancreatic fistula: is it possible? Pancreatology. 2013;13: 423-428.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Surgical Clinical Reviewers, Surgeon Champions, and pancreatic surgeons who participated in the Pancreatectomy Demonstration Project at the institutions listed below. We also wish to thank the leadership of the American College of Surgeons and of ACS-NSQIP for the opportunity to conduct the demonstration project.

• Albany Medical Center

• Baptist Memphis

• Baylor University

• Baystate Medical Center

• Beth Israel Deaconess

• Boston Medical Center

• Brigham & Women’s Hospital

• California Pacific Medical Center

• Cleveland Clinic

• Emory University

• Hospital University Pennsylvania

• Intermountain

• Indiana University University

• Indiana University Methodist

• Johns Hopkins Hospital

• Kaiser Permanente SF

• Kaiser Walnut

• Lehigh Valley

• Massachusetts General Hospital

• Mayo- Methodist

• Mayo-St Mary’s

• Northwestern University

• Ohio State University

• Oregon Health Sciences Center

• Penn State University

• Providence Portland

• Sacred Heart

• Stanford University

• Tampa General Hospital

• Thomas Jefferson University

• University Alabama

• University of California Irvine

• University of California San Diego

• University Iowa

• University Kentucky

• University Minnesota

• University Texas Medical Branch

• University Virginia

• University Wisconsin

• Vanderbilt University

• Wake Forest University

• Washington University St. Louis

• Winthrop University

Conflict of Interest

Grant support was from the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas Grant no. RP101207-P03, UTMB Clinical and Translational Science Award #UL1TR000071, NIH T-32 Grant no. T32DK007639, and AHRQ Grant no. 1R24HS022134. The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the hospitals participating in the ACS NSQIP are the source of the data used herein; they have not verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived by the authors. BLH is an Associate Director of the ACS NSQIP for the American College of Surgeons and receives a consultant fee from ACS for this role.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Discussant

Dr. Mark P. Callery (Boston, MA): “Dr. Cooper, by using a large NSQIP database, you have shown that neoadjuvant therapy prior to pancreatic cancer resection is safe. It does not increase a patient’s risk of death and overall morbidity. Let us hope your data can help dispel the myth that neoadjuvant therapy is dangerous. The low rate (12.7 %) of such therapy identified in your dataset is not surprising. That said, your work is important as it can now inform the reluctant that neoadjuvant therapy is a safe sensible approach in select patients, especially those with borderline resectable disease. Why do you think the mortality rates in this study are lower than most published postoperative mortality rates? Why do you think the rates of organ space infection are lower in the patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy? Finally, do you believe the participating institutions in this demonstration project somehow confound the findings and their interpretation? Thank you and congratulations to you and your coauthors.”

Closing Discussant

Dr. Cooper (Houston, TX): “Dr. Callery, thank you for your kind comments and insightful questions. I think the mortality rates in this study are likely lower than those in most published studies because a significant majority of the institutions that participated in the Pancreatectomy Demonstration Project meet the Leapfrog criteria for high-volume institutions for pancreatectomy.

I initially struggled a bit myself to understand why the rates of organ space infections are lower in the patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy; however, I was able to come up with two possible explanations. First, the rates of pancreatic fistula for the entire neoadjuvant therapy group were lower than those for the initial surgery group. Even though this difference only reached significance for the subset of patients treated with radiation, this may have been a key contributing factor as pancreatic fistulae are the most common cause of organ space infection in patients undergoing pancreatectomy. A second potential contributing factor may be that the patients in the neoadjuvant therapy group may have benefitted from some “prehabilitation” effect during the neoadjuvant therapy period that is not adequately measured by albumin, ASA class, and the other preoperative variables captured within NSQIP and that provided some protection against organ space infections.

I think the characteristics of the institutions participating in the Pancreatectomy Demonstration Project should certainly be kept in mind when interpreting the results of this study. As previously mentioned, many of these were high-volume institutions; however, it should also be noted that the institutions which are most well-known for and have the longest standing experience with the use of neoadjuvant therapy for treatment of pancreatic cancer were not participants in the Demonstration Project. In addition, 31 of the 43 participating hospitals contributed at least one patient to the neoadjuvant therapy group, so these patients were treated at a variety of different hospitals, which suggests that these results may be more generalizable than they might initially seem.”

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cooper, A.B., Parmar, A.D., Riall, T.S. et al. Does the Use of Neoadjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Increase Postoperative Morbidity and Mortality Rates?. J Gastrointest Surg 19, 80–87 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-014-2620-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-014-2620-3