Abstract

Forty-six mining-induced seismic events with moment magnitude between −1.2 and 2.1 that possibly caused damage were studied. The events occurred between 2008 and 2013 at mining level 850–1350 m in the Kiirunavaara Mine (Sweden). Hypocenter locations were refined using from 6 to 130 sensors at distances of up to 1400 m. The source parameters of the events were re-estimated using spectral analysis with a standard Brune model (slope −2). The radiated energy for the studied events varied from 4.7 × 10−1 to 3.8 × 107 J, the source radii from 4 to 110 m, the apparent stress from 6.2 × 102 to 1.1 × 106 Pa, energy ratio (E s/E p) from 1.2 to 126, and apparent volume from 1.8 × 103 to 1.1 × 107 m3. 90% of the events were located in the footwall, close to the ore contact. The events were classified as shear/fault slip (FS) or non-shear (NS) based on the E s/E p ratio (>10 or <10). Out of 46 events 15 events were classified as NS located almost in the whole range between 840 and 1360 m, including many events below the production. The rest 31 FS events were concentrated mostly around the production levels and slightly below them. The relationships between some source parameters and seismic moment/moment magnitude showed dependence on the type of the source mechanism. The energy and the apparent stress were found to be three times larger for FS events than for NS events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As the underground mining advances to greater depths, the stresses in the rock mass increase, and as a consequence the level of induced seismicity usually increases. Mine seismicity poses a hazard to the mine personnel and infrastructure and therefore it has become a major operational issue and a challenging planning factor for most underground mines worldwide, especially at depths greater than 900–1000 m. As a result the importance of a reliable estimation of the seismic source parameters and understanding of the nature of the seismic events increases.

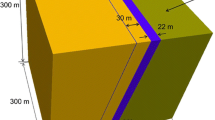

Kiirunavaara mine (LKAB) is an underground sublevel caving iron ore mine located in Norrbotten county, Lapland Province, Sweden, and known as one of the largest and most modern underground mines in the world (Fig. 1a). The mine has been seismically active since 2007 and the seismic activity increased as mining advanced deeper. More than 1000 seismic events per day have been recorded in the whole mine during recent years. One of the most seismically active and also rockburst/rockfall prone areas in the mine is the production area called Block 33/34 (Fig. 1b). Given the increased seismicity in the mine and the hazard it poses to production as well as the safety of the mine personnel, a need to study the source parameters of the damaging events in the block and the correlation between the source parameters and associated damages was identified.

a Geographical location of Kiirunavaara LKAB mine, b perspective view of the mine, showing the position of Block 33/34 (modified from https://www.lkab.com)

The whole study incorporates three components: firstly, seismic source (which focuses on a seismic event source evaluation), secondly, rock damage resulting from seismic loading (detailed study of the characteristics of the damage, and correlation with the local geological structures, rock mechanical parameters and local stresses), and thirdly, correlation between the source parameters and rock damage characteristics. This study describes the results from the first component which concentrated on detailed characterization of the sources of 46 seismic events that possibly caused damage underground in Block 33/34 between 2008 and 2013. The hypocenter location, magnitude, radiated energy, apparent stress, source dimensions, etc., were calculated by manual processing (experienced human picking of P- and S-wave arrivals). The seismic events were separated into two types of seismic source mechanisms (shear and non-shear events) depending on the E s/E p ratio and the relationships between the source parameters were studied for these two types. The spatial distribution of these events and the dependence of some source parameters on the mechanism were also investigated.

The results from this study are to be used also for further evaluation of the existing techniques for short-term seismic hazard assessment in the seismically active deep mines.

Data

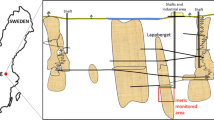

The seismic event that potentially caused damage in each one of the cases was determined by the mine personnel. In some cases the relationship between the seismic event and damage was not absolutely certain such as in the cases of seismic events followed by aftershock series. That is why the 46 events which are studied here include also nine aftershocks of two of the main events. The moment magnitudes of the aftershocks ranged between −1.3 and 1.1 and the moment magnitudes of the main events ranged between −1.2 and 2.1. By 2014 the seismic system at Kiirunavaara mine consisted of 215 geophones (88 triaxial and 127 uniaxial), most of which with cut-off frequency of 4.5 or 14 Hz, installed at levels between 341 and 1502 m along a distance of ~4100 m (Fig. 2).

Vertical projection looking east showing the seismic monitoring sensors (green pyramids—uniaxial sensors and yellow cylinders—triaxial sensors) in Kiirunavaara mine, the studied seismic damaging events (red spheres—fault slip FS and blue spheres—non-shear NS) and block 33/34 (black dashed lines). The plot shows only the sensors that recorded the studied seismic events. It is made in mXrap software (Harris and Wesseloo 2015)

The study area measures ~500 × 600 × 500 m, at levels between 850 and 1350 m. The seismic events were recorded by the seismic system at distances from 34 m up to 3200 m (Fig. 2). The number of the sensors that recorded the events varied between 6 and 130. The number of sensors varied in a large range due to the multiple stages of the seismic system upgrade over time. The first major upgrade started in August 2008–June 2009 (adding 112 sensors) followed by July 2012–September 2013 upgrade (adding 95 sensors) (Dineva and Boskovic 2017). The smallest number of sensors (6–8) is for the events that occurred before and during the first stage of the system upgrade. These events are also some of the smallest, with moment magnitudes from −0.5 down to −1.3. One of the events on November 17, 2008 was with magnitude 1.7 and initially recorded by 19 sensors but some of them were further than 1400 m (the maximum considered distance) and for some during the processing were found very large residuals and they were excluded.

A set of 2089 waveforms of 46 studied events were obtained together with a catalog of the routinely calculated seismic source parameters from the LKAB database. All the parameters of the seismic events in the LKAB database are calculated by IMS (Institute of Mine Seismology, www.imseismology.org). The waveforms were used for re-processing of the seismic events and refined estimation of the seismic source parameters (hypocenter location, local magnitude, seismic moment, moment magnitude, radiated seismic energy, seismic potency, corner frequencies, apparent volume, source length, apparent stress, static and dynamic stress drop). Examples of manually processed triaxial waveforms for a smaller event of magnitude 0.2 and larger event of magnitude 1.7 recorded at different distances on 23 August 2012 and 24 August 2012, respectively, are presented in Fig. 3

Examples of triaxial waveforms of X, Y, Z components of a smaller event of magnitude 0.2 recorded on 23rd August 2012 at distances of 118, 594 and 1441 m (left) and of a larger event of magnitude 1.7 recorded on 24th August 2012 at distances of 99, 539 and 1452 m (right). The horizontal (time) scale of all plots is the same. The vertical scale (velocity amplitude) of the seismograms is different and shown in the left upper corner

Source parameter determination

Models of seismic sources and methods for source parameters determination developed for natural earthquakes can be used also for determination of source parameters of mine tremors (Gibowicz and Kijko 1994). There are some additional source parameters specifically developed for mining events (e.g., E s/E p ratio, energy index, apparent volume). The IMS TRACE software was used for calculation of the hypocenter locations and all other source parameters. It uses the natural earthquake models to calculate the source parameters of the seismic events. As a rule, the parameters of the recent seismic events in Kiirunavaara mine are calculated routinely by IMS using data from 18 sensors for each event and the same software. The older seismic events, before the seismic system upgrade were recorded by smaller number of sensors and all of them were used. Our aim was to add data from more sensors and to refine the parameters using TRACE software.

Hypocenter locations

According to Mendecki et al. (2007), a reasonable accurate location for rock mechanical purposes is important for indication of the location of potential rockbursts, quantification of seismic sources, interpretation of seismic events and interpretation of seismicity (clustering, migration, spatio-temporal gradients of source parameters, etc.). In this study our aim was to improve the location accuracy as best as possible compared to the routine processing by more accurate picking of the arrival times, using data from more sensors with the best possible azimuthal coverage.

In 1993, Mendecki stated that about 60% of the automatically processed data are reliable and 40% are subjected to errors. With more advanced algorithms and much more computer power, the quality of the automatically processed events and their reliability improved to 75% of all data and the remaining 25% accounts for those events that are complex and the system is not able to identify (Prof. Cornel du Toit, IMS, personal communication, 2015). Specifically for Kiruna mine, Du Toit further states that the reliability reduced to 50% due to the complex rock mass ray paths. The rockmass in Kiruna is known to be highly fractured with inclusions of clay and void areas.

Therefore, for more accurate hypocenter locations it was necessary to verify first the P- and S-wave arrivals which were already routinely obtained (usually from ~18 sensors) and if possible add more arrivals. The arrival times were picked manually (experienced human picking). The algorithm of the implemented location method is found in the Appendix.

All seismograms recorded by the sensors within a distance of up to 1400 m were used in this study. Only very good (clear) P- and/or S- wave arrivals with good signal-to-noise ratio were enabled. Examples of the picks are shown in Fig. 3. The seismograms from the triaxial sensors were rotated into the local coordinate system P-SV-SH for more accurate S-wave arrival pick. All event locations were automatically calculated after manual picking of arrival times, with subsequent check and refinement of these times, until the location residual was reduced to less than 20 m and the average hypocentral distance (AHD) to less than 3%. AHD is the ratio of the mean distance between obtained hypocenter and all the sensor sites, which were used in the location procedure. The P- and S-wave arrival residuals larger than 20 m (difference between observed/picked arrival and expected arrival, multiplied by V P or V S, respectively) were disabled to reduce AHD up to 3%. The re-calculated hypocenters were used for further re-calculation of the source parameters. A flowchart on Fig. 4 shows the process of manual picking of arrival times and their subsequent refinement and location and source parameters re-calculation (refinement).

The refined hypocenter locations for 46 events were calculated with location residuals between 2 and 10 m with the majority up to 9 m. For comparison, the location residual for the routinely calculated hypocenters ranged between 3 and 22 m with the majority between 5 and 10 m (Figs. 5, 6). The coordinates of the re-calculated hypocenters were compared with the routinely calculated ones. The distance between the new and old locations ranged between 2 and 61 m, with the majority of cases up to 20 m (Fig. 6). Large distance between the refined and routine locations (above 55 m) was observed in three cases where the routine hypocenter residual was larger (Fig. 6). The largest distance between the old and new hypocenters, 61 m was found for the event on November 17, 2008, with magnitude 1.7. This large distance between the hypocenter can be explained by the inclusion of arrival times with very large individual residuals (~90 m) during the initial routine calculations. After they were excluded the hypocenter residual dropped from 22 to 5 m and the hypocenter moved at large distance (event #1 on Fig. 5). The refined hypocenter residual has improved (decreased) the routine hypocenter error by 23% on average (Figs. 8, 9). The largest change in the source parameters after the refinement was in the seismic energy (39% increase), followed by the apparent stress (24% increase) and less change in the seismic moment and its derivative, the moment magnitude (7 and 5% decrease, respectively). The E s/E p ratio, which was used for classification of seismic event source mechanism type (shear/fault slip—FS or non-shear—NS) changed for 10 out of 46 events, for 5 events from NS to FS, and for another 5 in the opposite way. In overall the E s/E p ratio increased by 14%.

The coordinates of the re-calculated hypocenters were compared with the routinely calculated ones. The distance between the new and old locations ranged between 2 and 61 m, with the majority of cases up to 20 m (Fig. 7). Large distance between the refined and routine locations (above 55 m) was observed in three cases where the routine hypocenter residual was larger (Fig. 7). The largest distance between the old and new hypocenters, 61 m was found for the event on November 17, 2008, with magnitude 1.7. This large distance between the hypocenter can be explained by the inclusion of arrival times with very large individual residuals (~90 m) during the initial routine calculations. After they were excluded the hypocenter residual dropped from 22 to 5 m and the hypocenter moved at large distance (event #1 on Fig. 5).

It should be noted that the hypocenter residual is the one estimated by the software. The real residual could be larger. A comparison between the real locations of 14 specially designed mine blasts (validation blasts) and their estimated locations by the software was performed on the data obtained from the mine personnel, showed difference between 4.2 and 27.5 m with a software residual ranging mostly between 5.0 and 19.5 m.

While the routine locations were calculated with data from typically 18 sensors and a maximum 22 sensors, the refined hypocenters were calculated with more data from up to 130 sensors but mostly between 20 and 40 sensors (Fig. 8). For each type of location (routine or refined) the location error generally increased with the number of used sensors and P- and S-arrival times used for the location. This trend is clearer for the routinely calculated locations with residuals up to 21 m although for the typical 18 sensors there are a large variety of residuals from 4 to 21 m. For the refined locations the residuals initially increased with a number of sensors but stayed almost the same ~8.9 m for more than 40–50 (Fig. 6).

Source parameters

Dynamic source parameters of each seismic event have been calculated from P- and S-wave spectra using the IMS TRACE software, assuming a far-field point source model. The corner frequencies of P- and S-wave spectra for each event were estimated automatically by the software after stacking the spectra corrected for inelastic attenuation (separately for P- and S-waves). The Brune model (Brune 1970, 1971) with a slope of −2 (\(\omega^{ - 2}\)) was used to fit the spectra. The formulas for calculation of all dynamic parameters in this study with the corresponding references are given in Table 1. Most of the source parameters are the traditional parameters introduced for natural earthquakes. The additional parameters for mining-induced seismic events calculated here are the energy ratio (E s/E p) and the apparent volume.

The basic source parameters, as seismic moment, energy, and corner frequency are obtained for both P- and S-waves. The seismic moment presented here is the average of the seismic moments of P- and S-waves. The energy is the sum of the seismic energy of both waves. Only the S-wave corner frequency was used for calculation of the source radius and source volume, which depend on the corner frequency. It is obtained more reliably than the corner frequency of P-wave as the time window used to calculate the P-wave amplitude spectrum (time between P- and S-arrivals) in many cases is very short and the spectrum h small number of points. All dynamic source parameters are calculated from the vertical components because uniaxial sensors have only vertical component. In this way the data from different sensors is of the same type.

The source radius is inversely proportional to the corner frequency (f c) dependent on the source model. In this study the model of Brune et al. (1979) was used (K c = 0.33). This model gives a slightly smaller radius than the original model of Brune (1970, 1971) (K c = 0.37) but a larger radius than the Madariaga model (1976) (K c = 0.21).

The apparent stress is defined as the average shear stress loading the fault plane to cause slip multiplied by the seismic efficiency, defined as the energy radiated seismically and the total energy released by the earthquake (Wyss and Brune 1968). This parameter is not model dependent. It is defined also as the amount of radiated seismic energy per volume of coseismic inelastic deformation that radiated seismic waves. It is calculated as the ratio between the radiated energy divided by the seismic moment, multiplied by the rigidity at the seismic source. The formula for its calculation is shown in Table 1. Since mining-induced seismic events have not only a double-couple component but in many cases also isotropic and CLVD components this parameter is preferred instead of the stress drop which is defined for double-couple sources (Mendecki 1997). Shear modulus of 3 × 1010 Pa is used for calculation of the apparent stress.

A source parameter used in the past years specifically for the mining-induced seismic events is the E s/E p ratio (Table 1). The E s/E p ratio is introduced as a routine parameter in mining seismology as a proxy for the type of focal mechanism generating the seismic event. It was estimated that the initiation of events with ratios of E s/E p <10 involves tensile (non-shear) failure mechanism and/or volume change and events with a larger ratio of E s/E p, predominantly shear failure mechanism (e.g., Gibowicz et al. 1991; Gibowicz and Kijko 1994). Moreover, McGarr 1984 and Gibowicz and Kijko 1994 found that mine-induced seismic events with large moment magnitudes have a high E s/E p ratio. This ratio for natural shear events was found to be in the order of 20–30 (Boatwright and Fletcher 1984). Kwiatek and Ben-Zion 2013 analyzed the acoustic emission from 539 aftershocks (M L −5.23 to −2.41) of M W 1.9 mainshock and found lower bound of E s/E p for shear of 4.5. They found many events to have E s/E p <1, interpreted as pure tensile mechanism.

Another parameter, used specifically for mining-induced seismic events is the apparent volume, defined in a similar way as the seismic volume. Instead of the stress drop (Δσ), the apparent stress (σ a) is used in the formula for the seismic volume, since it is less model dependent, to obtain the apparent volume. The apparent volume is defined as the volume of coseismic inelastic deformation that radiated seismic waves. In general, Δσ ≥ 2σ a (Savage and Wood 1971). That is why the stress drop is replaced by the doubled apparent stress in the formula for the apparent volume (Mendecki 1993) (see Table 1 for the final formula).

The obtained refined source parameters vary in wide ranges as presented in Table 2. This result is not surprising as the moment magnitude of the studied event differs by more than three magnitude units.

On average the refined source parameters showed an increase in the radiated energy (39%), apparent stress (24%), and E s/E p ratio (14%). The parameters that showed a reduction were seismic moment (7%) and moment magnitude (5%) (Fig. 9). One of the events (event 4, 2009-02-04) showed a drastic change in the source parameters and affected the average results largely.

Non-shear and shear event classification

Depending on the E s/E p ratio the seismic events were separated into two different types of failure mechanism: non-shear events (NS, E s/E p <10, 15 events) and shear (fault slip) events (FS, E s/E p >10, 31 events). The non-shear events occurred pretty much at every level (Fig. 10) as compared to shear events where the majority occurred between levels 960–1080 m (Fig. 11).

Spatial distribution of the events with non-shear (NS, blue spheres) and fault slip (FS, red spheres) mechanism: size is proportional to local magnitude. The plot is made in mXrap software (Harris and Wesseloo 2015)

The E s/E p ratio for the shear events ranged mostly between 10 and 35 but some single values were larger, reaching up to 130. The sensitivity of E s/E p values to changes in the source locations was evaluated by comparing the results obtained independently by two of the authors after manual picking of P- and S-wave arrivals. No significant changes in E s/E p were observed. The type of the mechanism (FS or NS) changed only in two cases.

After refinements of the source parameters, the mechanism type changed for 10 events out of 46 events—5 changed from FS to NS, and 5 in the opposite way, from NS to FS (Table 3). For 27 events the mechanism remained FS and for 9 NS. Even though for 36 events the source mechanism type remained the same, some large changes in the E s/E p ratio were observed for 5 events (# 8, 9, 14, 25, 46) (Fig. 5).

The results show that the studied events, both NS and FS, occurred mostly in the footwall, close to the ore contact and their spatial distribution followed the orientation of the orebody curvature. The FS events are concentrated in the upper levels (around the production and slightly below) whilst NS events are distributed almost in the whole range of levels with many of them below the production (Fig. 11). During the period from 2008 until 2013 the production in Block 33/34 was between levels 935 and 1022 m.

As expected, in general the FS events had larger magnitudes than the NS events. This observation is in agreement with Ortlepp source mechanism classification (Ortlepp 1992) that is widely used. In this study FS mechanisms were obtained for comparatively larger moment magnitudes up to 2.1 while NS events were obtained for magnitudes up to 1.1. The E s/E p ratio for NS seismic events ranged between 1.2 and 8.9, and for FS events between 11.0 and 126.0, respectively (Fig. 12). For the NS events the E s/E p ratios did not show any trend with the moment magnitudes; however, for the FS seismic events a gradual increase in the upper bound of the E s/E p ratio with moment magnitude was observed (Figure).

Relationship between the seismic source parameters for different mechanism type (FS or NS)

The relationships between the source parameters were explored looking for differences between non-shear (NS) and shear events (FS): energy versus seismic moment, apparent stress versus moment magnitude, and source radius versus moment magnitude.

The energy showed a good correlation with the seismic moment for both types of seismic events. The energy of the FS events was found to be higher than the energy of NS events for the same seismic moment, on average three times larger (~0.5 log E difference) (Fig. 13).

The apparent stress showed a relative increase with moment magnitude for both FS and NS events. For 2 magnitude units (moment magnitude from −1 to 1) the apparent stress increased ~10 times for FS events and ~14 times for NS events (Fig. 14).

On average the apparent stress for the FS events is approximately three times larger than the apparent stress of the NS events for the same moment magnitude (~0.5 logσ a difference) (Fig. 14). Larger apparent stress for the FS can be expected as this parameter is proportional to the ratio of the seismic energy and the seismic moment (see Table 1) and the energy of the FS events is larger than the energy of the NS events (Fig. 13).

It has to be noted that the correlation between the apparent stress and magnitude is moderately strong (coefficient of determination 0.59 and 0.68 for FS and NS events, respectively) and some NS events have apparent stress close to that of the FS events.

The source radius and moment magnitude have shown a moderate correlation for FS and NS events. A general trend of increase in the source size with moment magnitude for all events is noticed, but without significant difference between FS and NS events (Fig. 15). Two outliers from NS and FS are observed in 2009 with unexpectedly low corner frequencies, which resulted in large source size.

The apparent volume also showed difference for both types of mechanisms (Fig. 16). It is approximately three times larger for NS events than for FS events for the same magnitude (~0.5 log V a difference).

Sketch showing the idea behind apparent velocity weighting in Eq. (7) \(v_{{{\text{P}}_{i} ,}} v_{{{\text{S}}_{i } }}\) for tested source location (Event) using calculated apparent velocities for calibration blasts (j) and site/sensor (i) (\(v_{{{\text{P}}_{i} ,}} v_{{{\text{S}}_{i } }}\)). The distances between calibration blasts and tested source location are d j (figure and corresponding text courtesy of Dmitriy Malovichko, IMS)

Discussion and conclusion

To ensure reliable seismic source parameters required for further seismic related problems and rock damage hazard, good quality hypocenter locations should be obtained. Good quality locations do not only affect consecutive phases of the seismicity analysis, but also change the source parameters and reduce their errors. Our task during this study was to improve the hypocenter locations for future analysis (short-term hazard back analysis and rock damage hazard) related to these seismic events. Therefore, obtaining good quality locations was the first very important task for the larger project.

Better refined hypocenter locations and source parameters were obtained by manual refinement of the available P- and S- wave arrivals and adding arrivals from more distant sensors. The routine analysis of the seismic records in the mine usually includes only the first 18-20 sensors and the hypocenter location is obtained without extensive refinement. The refined hypocenter locations were obtained with a much larger number of phases from more sensors and as a result with reduced estimated residual (max 10 m instead of 22 m). We have to stress that the same location method was used for both the routine and refined hypocenters. Only the number of P- and S-arrival times, and correspondingly the azimuthal coverage were different. The major improvement was the refined arrival times.

The comparison between the location residuals and the number of sensors for both data types—routine and refined data, showed that the location residuals increased with the number of sensors (Fig. 8). There is a clear trend in the refined hypocenter residuals, with some increase for the smaller number of sensors <40 and then almost the same residual ~9 m even for the maximum 130 sensors. On contrary, the routine hypocenter residuals increased sharply with the number of sensors, reaching 18–21 m for less than 30 sensors. The comparison showed that for the same number of sensors the residuals of the refined locations were much smaller (2–3 times in some cases) than the residuals of the routine hypocenters. The conclusion was made that probably the refinement of the arrival times is more important for a reduction of the hypocenter location residuals than adding more data.

The distance between the new and old locations ranged between 2 and 61 m, with the majority between 2 and 35 m (Fig. 5). The largest distance of 62 m was obtained for the event on November 17, 2008. This event (#1) was recorded initially by 19 sensors, at the time when the seismic system did not have a lot of sensors. Due to careful analysis a number of P- and S-waves arrivals were found to have very large errors, e.g., the sensors were wrongfully associated with the event. Some of the sensors were at very large distances (>1400 m) and were excluded. The result of the refinement was the large shift in the hypocenter location but also a drop of the hypocenter residual from 22 m (the maximum in our database) to 5 m.

The corner frequencies for the seismic sources varied between 9 and 240 Hz, increasing with decreasing of the magnitude, as expected. They were obtained automatically by stacking of P- and S-wave spectra, corrected for intrinsic attenuation with a standard slope of the high-frequency part of −2 (ω −2). It was noticed that in some cases the automatic fit between the model and the spectra is not very good and the slope could be larger than −2. Further manual refinement of the slope would change some of the corner frequencies to higher values, which subsequently would reduce the source size and the apparent volume (because of the increase in the stress drop) (see the formulas in Table 1). The poor corner frequencies can possibly explain the poor correlation between the moment magnitude and the source size (Fig. 15) and the lack of difference in the source radius for NS and FS events for the same magnitude. The relationship between the apparent stress and the magnitude (Fig. 16) would change too.

The refined source parameters of the seismic events studied here varied in large ranges (Table 2), which was not a surprise taking into account that the magnitude range of all studied events was 2.4 magnitude units, from −1.3 to 2.1. The important result is that the change in the hypocenter locations and adding more data with better azimuthal coverage resulted in seismic source parameters change. This can be explained by two factors. First, the hypocentral distance is used for correction of the spectra for the attenuation. The correction affects the spectral model parameters—more the corner frequency and less the low-frequency asymptote of the spectra. Second, the distance is included also in the formula for the seismic moment (~distance) and the energy (~distance2) (Table 1). Third, the larger number of sensors, respectively, larger number of accepted P- and S-arrivals, increased the number of spectra for the stacking and made the source parameters more stable. The result of this study showed the largest change in the source parameters after the refinement in the seismic energy (39% increase), followed by the apparent stress (24% increase) and less change in the seismic moment and its derivative, the moment magnitude (7 and 5% decrease, respectively). The E s/E p ratio, which was used for classification of seismic event source mechanism type (shear/fault slip—FS or non-shear—NS) changed for 10 out of 46 events, for 5 events from NS to FS, and for another 5 in the opposite way. In overall the E s/E p ratio increased by 14%.

The obtained values for the seismic moment and the apparent stress for Kiruna mine are in the same order as the values for the seismic events in deep gold mines in South Africa (Richardson and Jordan 2002; Sellers at al. 2003). For the events with similar seismic moment the apparent stress is similar also to the range of this parameter in Strathcona mine, Ontario, Canada (Trifu et al. 1995).

More than 90% of the studied events were located in the footwall with a cluster formed along the orebody and footwall contact, following the curvature orientation (Fig. 11). Interestingly, the orebody is thinner in the area where the event cluster was concentrated. The shape and location of the event cluster could be due to a number of factors, such as high stress concentration, presence of weak or clay zones or geological structures. However, no solid conclusion could be derived during this study. At this moment we cannot explain either the concentration of the FS events mostly around the production levels or slightly below (from 850 m down to 1160 m) and the random distribution of the NS events in the whole range from 930 down to 1350 m (Fig. 10). For comparison the production in Block 33/34 from 2008 until 2013 was between levels 935 and 1022 m.

Comparison of the relationships between some selected source parameters and moment magnitude was also explored to obtain a difference in the general trend of these parameters for NS and FS seismic events separately. The relationships for the seismic energy, energy ratio E s/E p, apparent stress, source radius, and apparent volume were considered as these source parameters will be correlated later with damage characteristics (severity of the damage, damage mechanism and location). A few important observations were made as a result of the comparison of the source parameters of NS and FS events. First, the number of the FS events was twice larger than the number of NS events and there were larger magnitude FS events (Fig. 12). This observation is important as it shows that it is more probable that FS events can cause larger damage than NS events. Second, the energy and the apparent stress (calculated from the energy and the seismic moment, Table 1), are ~3 times larger for FS events than for NS events for the same moment magnitude (Figs. 13, 14). Taking into account the importance of the seismic energy for the ground shaking (Bormann and Di Giacomo 2011) we can also conclude that the FS events should be more damaging than NS events for the same magnitude. The results from the previous studies from South Africa are consistent with our results even though most of our events have smaller seismic moments. Data for 16 mining-induced events with seismic moment in the range roughly from 1011 to 1014 N m in South Africa showed higher apparent stress and seismic energy, for double-couple (fault slip) events than for double-couple events with implosive component (non-shear) (McGarr 1992a, b, 1999).

The results from this study can be used also for verification of the scaling of the seismic events in the Kiirunavaara mine. The obtained relationship between the apparent stress and seismic moment showed that the apparent stress is ~\(M_{0}^{0.36}\) to \(M_{0}^{0.40}\) for the NS and FS events, with respective coefficients of determination 0.60 and 0.74. The scaling of the apparent stress with the seismic moment is consistent with the results obtained by Richardson and Jordan (2002) in South African deep gold mines for seismic events with similar seismic moment and apparent stress.

As a result of this study a few main conclusions were made. First, refined hypocenter locations and source parameters are required for special studies on the seismic hazard and correlation between the seismic source parameters and parameters of the rock damage in underground mines. The refinement using careful manual re-processing can improve the location and its residual (error) but also the seismic source parameters. Second, the mechanism of the seismic source has to be taken into account when various relationships between the source parameters and the size of the event (e.g., moment magnitude or seismic moment) are considered. On average the fault slip (FS) events could release more seismic energy than the non-shear events (NS) for the same magnitude, and as a result to be more damaging. Third, the corner frequency and the seismic source parameters that depend on it (source radius, stress drop, and apparent volume) need further improvement as the slope of the model spectra in most cases is larger than −2 (close to −3 and even larger).

References

Boatwright J, Fletcher B (1984) The partitioning of radiated energy between P and S. Bull Seism Soc Am 74:361–376

Bormann P, Di Giacomo D (2011) The moment magnitude M w and the energy magnitude M e: common roots and differences. J Seismol 15:411–427

Brune JN (1970) Tectonic stress and the spectra of seismic shear waves from earthquake. J Geophys Res 75:4997–5009

Brune JN (1971) Correction. J Geophys Res 76:5002

Brune JN, Archuleta RJ, Hartzell S (1979) Far-field S-wave spectra, corner frequencies, and pulse shapes. J Geophys Res 84(B5):2262–2272. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB084iB05p02262

Dineva S, Boskovic M (2017) Evolution of seismicity in Kiruna Mine. In: Wesseloo (ed) 8th International Conference on Deep and High Stress Mining, Deep Mining 2017. Perth, Australia, p 18

du Toit C (2015) New location-dependent apparent velocity model at kiruna mine, IMS internal report, KIR-REP-VEL-201504-CDTv1

Gibowicz SJ, Kijko A (1994) An introduction to mining seismology. Academic Press, New York, p 396

Gibowicz SJ, Young RP, Talebi S, Rawlence DJ (1991) Source parameters of seismic events at the underground research laboratory in Manitoba, Canada: scaling relations for events with moment magnitude smaller than 2. Bull Seism Soc Am 81:1157–1182

Hanks TC, Kanamori H (1979) A moment magnitude scale. J Geophys Res 84:2348–2350

Harris PC, Wesseloo J (2015) mXrap software, version 5, Australian Centre for Geomechanics, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia. http://www.mXrap.com

Kanamori H, Anderson DL (1975) Theoretical basis of some empirical relations in seismology. Bull Seism Soc Am 65:1073–1095

Keilis-Borok V (1959) On the estimation of the displacement in an earthquake source and of source dimensions. Ann Geophys 12:205–214

Kwiatek G, Ben-Zion Y (2013) Assessment of P-and S-wave energy for small shear-tensile seismic events in deep SA mine. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 118:3630–3641

Madariaga R (1976) Dynamics of an expanding circular fault. Bull Seism Soc Am 66:639–666

McGarr A (1984) Some applications of seismic source mechanism studies to assessing underground hazard, In: Gay NC, Wainwright EH (eds) Rockburst and seismicity in mines, Symp. Ser. 6 (South Africa Inst. Min. Metal), pp 199–208

McGarr A (1992a) An implosive component in the seismic moment tensor of a mining-induced tremor. Geophys Res Lett 19:1579–1582

McGarr A (1992b) Moment tensors of ten Witwatersrand mine tremors. Pure Appl Geophys 139:781–800

McGarr A (1999) On relating apparent stress to the stress causing earthquake fault slip. J Geophys Res 104(B2):3003–3011. https://doi.org/10.1029/1998JB900083

Mendecki AJ (1993) Real time quantitative seismology in mines: keynote address. In: Young RP (ed) Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Rockbursts and Seismicity in Mines, Kingston, Ontario, Canada, Balkema, Rotterdam, pp 287–295

Mendecki AJ (1997) Quantitative seismology and rock mass stability. In: Mendecki AJ (ed) Seismic monitoring in mines, Chapman and Hall, London, Ch. 10, pp 178–219

Mendecki AJ, Lynch RA, ISS International Ltd, Malovichko AD (2007) Routine seismic monitoring in mines, VNIMI Seminar on Seismic Monitoring in Mines, pp 1–31

Nelder JA, Mead R (1965) A Simplex method for function minimization. Comput J 7:308–313

Olsson DM, Nelson LS (1975) The Nelder-Mead Simplex procedure for function minimization. Techtonometrics 17:45–51

Richardson E, Jordan TH (2002) Seismicity in deep gold mines of South Africa: implications for tectonic earthquakes. Bull Seism Soc Am 92:1766–1782. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120000226

Savage JC, Wood MD (1971) The relation between apparent stress and stress drop. Bull Seism Soc Am 61:1381–1388

Storn R, Price K (1995) Differential evolution—a simple and efficient adaptive scheme for global optimization over continuous spaces, Technical Report TR-95-012, International Computer Science Institute, Berkeley, CA, USA. http://www.icsi.berkeley.edu/techreports/1995.abstracts/tr-95-012.html

Wyss M, Brune J (1968) Seismic moment, stress, source Dimensions for earthquakes in the California-Nevada Region. J Geophys Res 73:4681–4694

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Hjalmar Lundbohm Research Center (HLRC) for funding this study. Ruth and Sten Brands foundation granted a scholarship to Emilia Nordström to visit the South African mines and other mining institutions, and explore their seismic monitoring systems and methods for seismic hazards and partially funded the research of Savka Dineva. We are grateful to the LKAB team: Christina Dahnér-Lindkvist and Mirjana Boskovic for a number of consultations and sharing their knowledge about the mine production and seismicity, rock damage and geological setting and for providing the data. Special thanks to the IMS team: Ernest C. Lötter and others for supporting our work with Trace and Vantage software. The text explaining the hypocenter location method (the Appendix, including Fig. 17) were prepared with highly appreciated help from Prof. Cornel du Tout and Dmitriy Malovichko from IMS. Paul Harris and Johan Wesseloo at Australian Centre of Geomechanics were very helpful with the mXrap software with their continual efforts for upgrading the quality of Fig. 11. Finally, we would like to thank Dmitriy Malovichko and an anonymous reviewer for their comments and very constructive suggestions, which helped to improve the quality of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Hypocenter location algorithm

Appendix: Hypocenter location algorithm

The algorithm of the implemented location method is based on the minimization of the travel time residuals (cost function), defined as follows:

This is a sum of the absolute differences between the picked P- and S-arrival times (\(t_{{{\text{P}}_{i} }}\)) and \(t_{{{\text{S}}_{i} }}\), respectively) and the theoretical arrival times \(\left( {t_{0} - \frac{{d_{i} }}{{v_{{{\text{P}}_{i} }} }}} \right)\) and \(\left( {t_{0} - \frac{{d_{i} }}{{v_{{{\text{S}}_{i} }} }}} \right)\) for these waves for a sensor i, that recorded the event at distance d i . Theoretical times are calculated with P- and S-wave velocities that depend on the sensor (apparent velocities), and can also vary from event to event. Propagation of the seismic waves along straight lines is assumed. Usually not all P- and S-wave arrivals are available (picked accurately) and that is why the actual cost function applies only to available (enabled) arrivals:

As the minimization of this cost function is unstable (can trap in local minimum) with the common optimization methods (e.g., Nelder and Mead 1965; Olsson and Nelson 1975) or differential evolution (e.g., Storn and Price 1995), the origin time t0 is ‘removed’ from the optimization following Mendecki (1997).

The t 0 parameter is defined as

for P- and S-wave. If the enabled number of P- and S-arrivals is \(n_{\text{P}}\) and \(n_{\text{S}}\), respectively (\(n\; = \;n_{\text{P}} + n_{\text{S}}\)), then the origin time can be estimated as:

which is simply the average origin time estimated for all available arrival times (\(\hat{t}_{0} = \bar{t} - \bar{\tau }\)), the average difference between the picked arrival times and estimated travel times. The more stable cost function to obtain only the hypocenter is defined as

In a simple case scenario the velocities are constant for the whole volume (homogeneous velocity model) but they can also be sensor-specific. In this case data from calibration blasts with known locations are needed. We assume that data from m calibration blasts with known locations but with unknown origin time are available. To obtain the apparent velocity for a calibration event the origin time and homogenous seismic velocities are inverted using the cost function

where\(R_{i}\) is the distance from the known (fixed) hypocenter of the event to sensor i, \(t_{{P_{i} }}\) and\(t_{{S_{i} }}\) are the picked (observed) arrival times for P- and S-waves, respectively, and v P and \(v_{S}\) are the unknown P- and S-wave velocities. \(w_{i}^{\text{P}}\) and \(w_{i}^{\text{S}}\) are the optimal P- and S-wave weights for site i. The default option is to use weights inversely proportional to the hypocentral distance to increase the relative importance of the nearby sensors and reduce the importance of the sensors that are far away. After the origin time \(\hat{t}_{0}\) and the homogeneous velocities are inverted the apparent velocities for site i are calculated as \(\frac{{R_{i} }}{{t_{{{\text{P}}_{i} }} - \hat{t}_{0} }}\) and \(\frac{{R_{i} }}{{t_{{{\text{S}}_{i} }} - \hat{t}_{0} }}\), respectively. These velocities are used further for calculation of the unknown hypocenters of the seismic events.

In case of inversion for unknown hypocenter the apparent velocity between site i and an arbitrary point \(x_{\text{a}} = \left( {x,y,z} \right)\) is estimated by

where \(v_{{{\text{P}}_{ij} }}\) is the inverted P-wave apparent velocity of site i for calibration blast j, and \(d_{j}\) is the distance between calibration blast j and point \(x_{\text{a}}\). A similar equation is used for apparent velocities of S-waves. Sketch in Fig. 4 illustrates the notations.

The final cost function that is used is

A set of 112 calibration blasts was used at Kiirunavaara mine including sources mostly distributed in production areas. The method for hypocenter location that was described here resulted in a significant reduction in the travel time residuals of the seismic events in the highly heterogeneous medium. The average location error, defined as the difference between the actual calibration blast location and estimated location, is 23.0 m using Eq. 8 compared to 41.1 m using Eq. 5 (du Toit 2015).

Figure 17 sketch shows the idea behind apparent velocity weighting in Eq. (7) (\(v_{{{\text{P}}_{i} ,}} v_{{{\text{S}}_{i } }}\)) for tested source location (Event) using calculated apparent velocities for calibration blasts (j) and site/sensor (i) (\(v_{{{\text{P}}_{ij} ,}} v_{{{\text{S}}_{ij } }}\)) The distances between calibration blasts and tested source location are d j (figure and corresponding text courtesy of Dmitriy Malovichko, IMS).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nordström, E., Dineva, S. & Nordlund, E. Source parameters of seismic events potentially associated with damage in block 33/34 of the Kiirunavaara mine (Sweden). Acta Geophys. 65, 1229–1242 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11600-017-0066-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11600-017-0066-1