Abstract

In this paper we examine how foreign actors capitalize on their ethnic identity to gain skills and capabilities that enable them to operate in a new and strange environment. We explore the mechanisms by which Bulgarian entrepreneurs in London use their ethnic identity to develop competitive advantage and business contacts. We find that the entrepreneurs studied gain access to a diaspora network, which enables them to develop essential business capabilities and integrate knowledge from both home and host country environments. The diaspora community possesses a collective asset (transactive memory) that allows its members to remove competition from the interfirm level to the network level (i.e., diaspora networks vs. networks of native businesspeople). Additionally, the cultural identity and networks to which community members have access provide bridging capabilities that allow diaspora businesspeople to make links to host country business partners and thus embed themselves in the host country environment. Thus, this paper adds to the growing body of work showing how foreignness can serve as an asset in addition to its better-known role as a liability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

International business research shows that firms operating outside their home countries face additional costs of conducting business activities (resulting, for example, from a lack of local institutional and business knowledge), commonly described as liabilities of foreignness (LOF)—costs that native actors do not usually incur (Hymer 1976; Zaheer 1995; Petersen and Pedersen 2002; Baik et al. 2013). Recent research, however, also points to the benefits that may result from foreignness, inviting us to view foreignness not only as a liability but also potentially as an asset (Nachum 2010b; Denk et al. 2012; Joardar et al. 2014). While the discussion on the assets of foreignness has been growing, scholars have only begun to investigate the scenarios in which positive or negative outcomes will prevail as a result of foreignness (Joardar et al. 2014). Some work investigating when foreignness is an asset, like that of Nachum (2010b), focuses on multinational enterprises (MNEs), but work in this vein focusing on the entrepreneurial ventures of immigrant entrepreneurs is still limited.

With this gap in mind, we investigate the conditions in which foreignness emerges as a valuable asset for transnational entrepreneurs (TEs) of micro and small enterprises. TEs have been defined in the literature as a subset of immigrant, ethnic entrepreneurs who, according to Drori et al. (2009, p. 1001), “migrate from one country to another, concurrently maintaining business-related linkages with their former country of origin and currently adopted countries and communities”.

This study builds upon research showing that learning about the specificities of the market and the environment is crucial for starting companies, because this knowledge allows entrepreneurs to locate and exploit business opportunities, as well as to develop operational efficiency (Penrose 1959; Spender and Grant 1996; Yli-Renko et al. 2001). In accordance with this notion, various studies have suggested that interorganizational affiliations generate knowledge acquisition and operationalization prospects (Dyer and Singh 1998; Lane and Lubatkin 1998; Larsson et al. 1998; Chetty and Holm 2000). Even though inter-organizational learning in a group setting has been viewed as essential for the successful operations of foreign companies, there is still a dearth of empirical qualitative studies scrutinizing the dynamics of learning in international business (Keupp and Gassmann 2009; Fletcher et al. 2013). This gap is even deeper within the context of the assets of foreignness literature, which welcomes further insight on the dynamics of how firms operate within networks (Denk et al. 2012).

Furthermore, although researchers have utilized traditional sociological approaches to examine entrepreneurial assets of specific ethnic groups (Fairlie and Meyer 1996; Dimitratos et al. 2016), the effects of transnationalism and the interplay between social, human and financial capital from home and host countries within ethnic groups remains largely unexplored but of significant importance (Ilhan-Nas et al. 2011). Prior research has shown that entrepreneurs’ transnationalism has resulted in new forms of cosmopolitan identity, which is still foreign in nature when compared to host countries’ identities (Wong and Ng 2002). Thus, it is a worthwhile endeavor to empirically reexamine the older notions of foreignness in light of the contemporary transnationalism pressures (Kloosterman and Rath 2001). Given that “the forms of transnationalism can be expected to vary significantly according to the nationality of the immigrant and the context of reception in ways that are currently not well understood” (Ilhan-Nas et al. 2011, p. 624), this study examines how TEs capitalize on their foreignness within a specific context, that of diasporas.

TEs operating in the locus of ethnic diasporas (the context where links and ties between home and host counties are maintained) are an excellent subject for researching how individuals capitalize on their foreignness within a transnational network. Looking at young companies and their intangible resources within the diaspora context (that is relationships and knowledge), as well as the way those resources are utilized, makes it possible to highlight the role of individuals (entrepreneurs) in turning foreignness into an asset. For these entrepreneurs, the diaspora network in which they embed themselves is not merely context—it is crucial to how their foreignness becomes an asset. According to Safran (1991), diasporas are defined as ethnic spaces characterized by a memory or a vision about, and commitment to, the home country, combined with a continuing relationship with the host country. However, since not all diasporas share the same dual identity trait (Radhakrishnan 2003), the characteristics of the transnational communities that facilitate the transformation of foreignness into an asset also deserve attention.

We look at foreignness on the individual level, as this is essential to the better understanding of organizational foreignness, especially in small entrepreneurial ventures (Joardar et al. 2014). In addition, the individual level of analysis allows us to probe the established understanding that foreign nationals are often observed to be in an unfavorable position when compared to the locals of the host country, due to their socio-cultural differences, lack of network embeddedness, and access to information (Jun et al. 2001; Joardar and Wu 2011). We believe that the tendency to associate liabilities with such characteristics as foreignness or outsidership arises almost by definition, because these characteristics define actors in terms of what they are not (or what groups they do not belong to) rather than what they are or what they do belong to—a negative, rather than a positive, identity. We will present evidence that changing our lens and defining the Bulgarian entrepreneurs we studied in a more positive sense—in terms of their “Bulgarianness” rather than their foreignness—points us clearly in the direction of the assets associated with their national identity.

This paper is a qualitative study of Bulgarian TEs operating in the UK, focusing on how these actors capitalize on their ethnic identity to gain access to a diaspora network, the Bulgarian diaspora, that incubates skills and capabilities that enable them to operate in a new and strange environment, namely the host country (the UK). We observe three assets of foreignness within this context. The first is a transnational network nurturing knowledge utilization and development of essential capabilities, accessible to only a relatively narrow group of actors. The second are the abilities of these entrepreneurs to enter this network and to bridge the home (the Bulgarian) and host (the British) market while operating within the diaspora community (ethnic spaces in the host country). The third consists in a unique mentoring environment found within the diaspora network that helps newer TEs learn from incumbents in the community how to apply knowledge gained from old experiences to the new situations in which they find themselves. This leads us to identify what makes the diaspora network such a valuable asset for the entrepreneurs who are able to join it and gain the trust of its incumbent members: its transactive memory (Argote 2015).

This paper adds to the ongoing discussion on assets of foreignness and also serves as a response to the call by Drori et al. (2009, p. 1016–1017) for research into how “TEs dynamically engage in imposing, demanding, resisting, and altering forms and strategies of business creation and development, controlling and manipulating their respective environments”. The observed ability of these actors to control and manipulate the host country environment reveals an important deviation from the established understanding that foreign nationals are in an unfavorable position.

Our paper proceeds as follows. We discuss the literature on the liabilities of and assets of foreignness and outsidership. We then present our methods and findings. The final section contains a discussion of the findings and conclusions.

2 Research Background

2.1 Ethnic and Transnational Entrepreneurship

The majority of research on international entrepreneurship examines three main types of businesses: “born global” companies, which internationalize at the moment of, or soon after, start-up (Madsen and Servais 1997; Knight and Cavusgil 2004; Lu and Beamish 2001); “born-again global” companies that internationalize after gaining competences and market share in the domestic market (Bell et al. 2003), and traditional large companies that internationalize gradually as a response to factors in the domestic and the global macro environment (Fernhaber et al. 2007). Although distinct streams have already emerged in international entrepreneurship research (Zucchella and Scabini 2007), some areas have largely escaped the attention of researchers despite their significance in the cross-national context. Transnational entrepreneurship is one of these.

As mentioned in the introduction, TEs constitute a subset of ethnic entrepreneurs. Broadly, ethnic entrepreneurs are immigrant entrepreneurs, generally treated as focusing on the domestic market; while they usually cater primarily to members of the same ethnic group (often occupying niche positions within ethnic enclaves), they may appeal to the broader community as well. They typically benefit from various forms of mutual support based on their membership in the local ethnic community (Auster and Aldrich 1984), and a number of authors have observed the existence of an “immigrant effect”, which refers both to the tendency of immigrants from at least certain ethnic groups to engage more frequently in entrepreneurship than the population at large, and to the role that immigrants play in facilitating FDI into their mother countries by the MNEs they work for (see Chung and Enderwick 2001). The role of ethnic ties in developing international trade has also been studied (see Rauch 2001).

What distinguishes TEs from other immigrant or ethnic entrepreneurs? Portes et al. (2002, p. 287) describe TEs as “depend[ing] for the success of their firms on their contacts and associates in another country, primarily their country of origin”; i.e., focusing on opportunities that span national borders (in a similar vein, see also Riddle et al. 2010). Drori et al. (2009, p. 1001) define TEs as “enact[ing] networks, ideas, information and practices for the purpose of seeking business opportunities or maintaining businesses within dual social fields”. Thus, while an ethnic entrepreneur focuses on the local market (whether the customer base consists of fellow immigrants, native-born locals, or both), the transnational entrepreneur bridges two markets, the local one and that of the home country.

In the literature on networking by ethnic entrepreneurs there is a focus on kinship ties (Basu 2004), and the role of these networks in transfer of knowledge about business practices from incumbents to newcomers has been noted (see Waldinger et al. 1990). The literature on diaspora networks has broadened the focus beyond kinship ties to include a much broader set of business ties based on ethnicity. In a review, Elo (2015) identifies diaspora networks as an under-researched area in international business—in particular with respect to resources and knowledge transfer—and cites Hernandez’s 2014 study of MNEs, which points to the literature on immigrant entrepreneurs as sources or brokers of knowledge transferred across borders but notes the lack of research on the mechanisms of such transfer. She also cites Muzychenko’s (2008) argument that cross-cultural entrepreneurial competences of the kind possessed by diaspora businessmen assist them in recognizing international business opportunities.

In two recent contributions, Moore (2016a, b) has explored how transnational identity, by being flexibly—even ambiguously—constructed, can serve as a tool for building bridges to other groups in both home and host countries, as well as diaspora communities in third countries. The use of national identity to bridge to multiple groups is a subject we will also deal with in this paper.

To sum up, a significant body of work has noted the role of ethnic and transnational entrepreneurs in facilitating trade and FDI, observing that this is largely due to the advantages that diasporas have in cross-border transfers of knowledge and the recognition of international business opportunities. This, however, begs the question of what it is that gives these groups of entrepreneurs an advantage in the sharing of such knowledge and what mechanisms are used to accomplish this, as well as to take advantage of the recognized opportunities. We will return to the questions about knowledge sharing below, in our discussion of networks and knowledge.

2.2 Liabilities and Assets of Foreignness

Liabilities of foreignness are defined as the extra tacit and social costs that foreign companies or individuals incur when operating abroad (Zaheer 1995; Eden and Miller 2004). The costs that constitute the LOF originate from foreign actors’ difficulty in the efficient management of the host country-specific knowledge sources and flows. Difficulties in communication and understanding are the principal causes of LOF (Schmidt and Sofka 2009). These liabilities translate into higher uncertainty, occurrence of business errors, risks, and lower productivity (Lord and Ranft 2000). It is necessary for foreign firms to overcome these burdens and secure coherence in inter-firm and intrafirm communication, a vital mechanism for the legitimization of business actors’ actions.

Prior research has identified that firms suffering from LOF possess fewer firm-specific and context-relevant advantages (Nachum 2003; Rangan and Drummond 2004) and experience difficulty in conducting internal knowledge transfers (Schmidt and Sofka 2009). Nevertheless, recent research has suggested that foreignness can be an asset as opposed to a liability (Nachum 2010b). Nachum finds that a cosmopolitan context like that of London is one in which liabilities of foreignness will be minimal or absent altogether. But what capabilities or resources of the firm itself could make its foreignness advantageous? Essentially, in Nachum’s treatment, these are the proprietary assets of a multinational company, or what in Dunning’s (1993) eclectic paradigm are referred to as “ownership advantages”, often enjoyed by foreign corporations in comparison with local (domestic) firms. These may consist of access to the globally deployable resources of such a corporate structure—resources unavailable to a young, entrepreneurial firm. But as for the latter, is it possible to identify and characterize scenarios in which such foreign actors are able to engage in the quick and efficient management of country-specific knowledge sources soon after internationalization, utilizing capabilities or resources that not only compensate any associated market uncertainty, but also lead to long-term competitive advantages?

The development of such a theoretical contribution, which is the goal of this study, is in line with research on assets of foreignness that “stresses the importance of knowledge transfer effectiveness to address the hazards of LOFs and their outcomes” (Denk et al. 2012, p. 328), and that seeks to “better understand the social processes underlying [TEs’] participation in socially integrated and complex inter-organizational relationships” (Denk et al. 2012, p. 331). Our study also shares the assumption that examining social processes in their institutional context is crucial for understanding the mechanisms through which foreign actors can leverage their foreignness (Orr and Scott 2008).

2.3 Networks, Knowledge, and Transactive Memory

Network research has shown the importance of social processes in entrepreneurial companies (Birley 1985; Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998). Networks serve as channels of knowledge and information, which can promote the effective alignment of knowledge or practices (Podolny 2001). The work of Schmidt and Sofka (2009) and Johanson and Vahlne (2009) implies that one of the main challenges TEs need to overcome is the inadequacy of their networks (cf. Ostgaard and Birley 1994). In addition, establishing inter-organizational relationships with partners of different nationality is likely to be challenging (Nachum 2010a), due to the complexities of bridging cultural differences between associates (Gulati 1995; White and Lui 2005). The costs of association with partners of the same kind (i.e., homophily) are significantly lower, while the probability of forming such a relationship is significantly higher (Ahuja et al. 2009; Nachum 2010a).

In this context, new TE actors might use the legitimacy they are granted by fellow ethnic diaspora members based on cultural and social commonalities to reduce the potential friction between the host and home countries’ cultures, which disrupts actors’ market integration capacity and undermines legitimacy (Zaheer 1995). As we have mentioned above, the role of ethnic networks in building the businesses of TEs has been stressed in the relevant literature (Drori et al. 2009), as has the possibility that the challenges that TEs need to overcome may be exceptionally difficult, as they face the institutional constraints of both the home and host countries, as well as to achieve embeddedness in both those environments (Yeung 2002; Drori et al. 2009). In this situation, TEs find themselves in need of knowledge about various areas, which Boissevain et al. (1990, p. 133–134) list as follows:

Before starting their enterprises, entrepreneurs need information about markets, the availability of premises, and laws. Once established, they need information about supplies, prices, warnings of market fluctuations, successful products, industrial needs, and so forth. They must also locate reliable specialists who can help them with fiscal problems and provide legal advice, capital, and labor.

This knowledge can be found in diaspora networks. The embedding of the knowledge characteristic of groups makes diaspora networks similar to communities of practice (CoPs) (Becerra-Fernandez and Sabherwal 2008). As defined by Wenger et al. (2002, p. 4), communities of practice are “groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis”. The people who participate in CoPs are united by shared interest or experience and operate in an informal environment, which nurtures creativity in solving mutual concern. Wenger (1998) suggests that the main output of the operation of CoPs is intangible and it is often knowledge, which could lead to improving performance. Having thus entered the domain of organizational learning, we wish to turn our attention to organizational memory, by which transnational entrepreneurs relate their prior global experiences to future actions. Transactive memory is a form of distributed organizational memory, which, as we will demonstrate, characterizes the collective memory of the TE community. The concept refers to the mechanisms by which “networks, ideas, information and practices […] within dual social fields” are utilized to generate “a collective system for encoding, storing, and retrieving information”, in which knowledge distributed across a group of individuals becomes a collective resource (Argote 2015, p. 198; see also Lewis and Herndon 2011). This system enables the users of such a system to connect to the best source of a desired resource, a capability that considerably improves collective performance (Ren and Argote 2011).

The knowledge within a transactive memory system carries has both explicit and tacit characteristics; the latter make its articulation a challenging task (Nonaka and von Krogh 2009). The difficulty of knowledge articulation is compounded by the fact that the knowledge a transnational actor possesses may reside in other members’ experiences (Levitt and March 1988). Transferring such difficult to articulate tacit knowledge is most easily and effectively achieved within an established social network (Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995). Due to the relational links between members, social networks are a key element for building efficiencies and competitive advantage (Skyrme 2000).

Furthermore, prior research suggests that such networks yield better results in various tasks than networks without that organizational memory (Rulke et al. 2000; Lewis 2004; Austin 2003). The reason for transactive systems’ superiority is their members’ propensity to enrich the knowledge and the competences of other incumbents (Argote 2015). As we will demonstrate, diaspora networks have integrated knowledge from both the home and the host environment, which enables their bridging function. The knowledge system in diasporas gives members prospects not only for enhancing their learning and providing them with the knowhow they need to adapt to, and operate in, the foreign environment, but also for providing the latest knowledge in the fields in which members operate.

For that reason, this study examines a contemporary diaspora setting as a complex knowledge management network that supports TEs in their efforts to embed themselves securely in the host country environment. The exclusive access that TEs gain in the network, based on their ethnic belongingness, may serve as an evidence of the assets stemming from their foreignness.

3 Methodological Approach

3.1 Data Context and Collection

Twelve cases of Bulgarian transnational entrepreneurial companies comprise the data context for this exploratory study. The companies are located and operate in the UK’s hot-spot of immigrant entrepreneurs—London. The 2011 labor force report of the UK Office for National Statistics reveals that London is home to 46% of all self-employed foreign-born workers in the country. Furthermore, Bulgarian entrepreneurs working in the city number 4537, which is 51.5% of the total of 8798 Bulgarian entrepreneurs in the UK (Centre for Entrepreneurs and DueDil 2014). The focus on the Bulgarian entrepreneurial community in London is justified by an important socio-economic event: Bulgaria’s accession to the European Union in 2007, which led to an increase of the economic and migratory exchanges between the UK and Bulgaria and the emergence of a new wave of transnational entrepreneurial firms. The selected entrepreneurial companies were founded or became transnational during or following Bulgaria’s accession.

Subjects for the investigation were drawn by the use of non-probability, purposeful sampling, from a list of more than 130 companies operating in the UK. The list was obtained from the British-Bulgarian Chamber of Commerce after an initial contact with Embassy of the Republic of Bulgaria.

Following the identification of the active case companies, dataset collection began. The London-based companies founded by Bulgarians were contacted via email and phone. All entries were screened by a survey for splitting transnational entrepreneurs, the ones who bridge nations and cultures, from ethnic entrepreneurs (the ones only serving a specific ethnic community). The survey contained questions used to identify the nationality of the entrepreneurs and determine whether their businesses can be classified as transnational. For the latter purpose, responses were obtained to a number of cross-checked questions regarding the owners’ cultural orientation (e.g. ethnic, acculturated, bicultural, multicultural), traveling patterns to home and other host countries in the last 12 months, degree of business affiliation to the home country, participation in organizations with links to the home country, and customers’ nationality and location. Additionally, the survey contained other questions designed to provide us with a better understating of the context in which the companies operate.

The questionnaire was designed in the light of the major definitions of transnational entrepreneurs and transnational entrepreneurial companies, which take into consideration the actors’ cultural orientation (Sequeira et al. 2009), operations within dual social fields (Drori et al. 2009), and frequency of travel (Portes et al. 2002) and other cross-border activities (Chen and Tan 2009).

In addition, the selected cases had to satisfy additional criteria. The selection criteria were that a firm conforms to Drori et al. (2009) definition of TEs (stated above, in the introduction), be a small business (with under 50 employees), be situated in Greater London, and self-declare as a consulting services provider. The reason for the last criterion is our interest in companies with high knowledge intensity and attempt to keep out companies whose competitive advantage is based on tangible as opposed to intangible assets, as these would typically follow strategies for offsetting liabilities by developing a superior competitive advantage based on factors other than the culture of the home country (for example, access to low-cost labor).

The data consist of a total of 63 semi-structured interviews with managers, employees and external stakeholders. The interview structure was designed for a series of 60–90 min semi-structured interviews. In each of the 12 companies studied, interviews were conducted with the owners (all of whom were males); all interviews were transcribed, coded, and analyzed. All of the interviewed entrepreneurs shared the characteristics of a “transnational” entrepreneur, namely to have business affiliations with both the home country (Bulgaria) and the host country (UK), which gives their businesses a bridging character. Table 1 summarizes the background of the interviewed transnational entrepreneurs, the entities they own in the host country as well details regarding their previous international business experience and personal characteristics. During the data collection, it became evident that none of the company owners had previously owned an enterprise either in Bulgaria or the UK before establishing the company in the UK. For the majority of the entrepreneurs, this was their very first international business experience, though a minority of them had had some international business exposure through previous jobs or/and internships prior to arriving in the UK.

In regards to business links or continuing affiliation with the home country, during the interview entrepreneur A said that he remains affiliated with Bulgaria through direct business links with some of the largest Bulgarian food companies as well as by working closely with Bulgarian suppliers and transportation companies. On monthly basis, he visits business partners in Bulgaria or they meet on UK ground. Entrepreneur B indicated that he remains closely linked to the home market through a number of Bulgarian client companies, which use his company’s services. Entrepreneur C, who provides consulting services to UK SMEs regarding opportunities for investing in, and trading with, Bulgarian companies, stated that his business could not survive if he did not continue to expand his portfolio of Bulgarian business partners. At the time of the data collection, he had more than 35 Bulgarian business partners across different industries. Operating in the same industry, entrepreneurs D and F both partner with a number of Bulgarian companies. Both entrepreneurs emphasized that such business relationships allow them to gain up-to-date information about the political and business environment there, which is paramount for attracting clients in the UK.

Entrepreneurs E and J have companies that provide legal services. Entrepreneur E, who specializes in tax and commercial law, is closely affiliated with the home country through his business contacts in the Bulgarian regulatory sector and through his growing portfolio of Bulgarian SMEs and consulting businesses interested in internationalizing in the UK. Similarly, entrepreneur J stated that approximately ten percent of his business clients are small companies in Bulgaria willing to expand as well as Bulgarian business investors searching for new opportunities abroad. The business success of entrepreneur G, who specializes in real estate and tourism, depends on his business partnerships in the hotel and tourist agency industries in Bulgaria. Like entrepreneur A, entrepreneur H, who owns a Bulgarian wine import company, has business links with Bulgarian wine producers and suppliers.

For Entrepreneur I’s business development company in the consulting sector, a full 50% of his clients come from Bulgaria. Entrepreneur K remains related to the home country by partnering with Bulgarian consulting agencies on a number of large business projects. Finally, entrepreneur L said that although his business is registered in London; he remains linked with the homeland through business offices in Bulgaria and his participation in a number of business clubs and associations there, which are a good source of new business clients and partners.

The participants and the first author speak the same language, which allowed the interviews to be conducted in Bulgarian. We believe that the shared lingual and cultural background facilitated access and improved interviewees’ engagement and responsiveness. Further interviews with at least three employees of each company were conducted (for a total of 40 interviews with employees) to garner additional insights into the strategies engaged in by the various firms. The owners suggested the employees interviewed for this purpose. They held various positions but were all referred to by the owners as experienced professionals who are in the core of the companies’ operations and active participants in the companies’ development. The interviewer was intentionally trying to test for differences in the perceptions of employees and managers. These conversations tended to be rather informal and of varying length, and were always conducted following the interview with the owner, and in his absence. Nevertheless, not surprisingly, the closeness of the relationship between the managers and the selected employees ensured that both side share similar understanding and vision for the business and the role of the diaspora in the companies’ journey. Given the absence of the owner during the interviewers, the interviewer had no reasons to believe that the employees’ statements did not reflect their true perceptions and attitudes.

We also conducted interviews with 11 independent informants, including a consultant specializing in European subsidies and the consul of the Bulgarian Embassy in London, as well as business owners and other professionals approached during social events organized by the Bulgarian City Club in London and the Bulgarian Embassy in London.

Observations were carried out by the first author during social events organized by the British-Bulgarian Chamber of Commerce, the Embassy of the Republic of Bulgaria, and individual actors’ business meetings, making it possible to gain direct insight into the entrepreneurs’ social representation strategies by observing how the entrepreneurs position themselves and initiate conversations, which was an important indicator regarding their strategies for embeddedness. Attending social events also led to 11 interviews, which were impromptu in nature, with actors from the entrepreneurs’ environment, including officials from the Bulgarian Embassy, the director of the British-Bulgarian Chamber of Commerce, Bulgarian business professionals working for British and international corporations, consultants based in Bulgaria, and other members of the Bulgarian diaspora in London. The events attended took place in August and September of 2011 and included two monthly meetings of the Bulgarian City Club. This club has long-standing relationships with the Bulgarian Embassy and the Chamber of Commerce but is also open to business professionals working in British or multinational companies.

3.2 Company Identification and Profiles

As shown in Table 2, the study is based on twelve TE companies, which operate in the service sector. Of the selected firms, all but two deliver high value-added services including business consulting, procurement, business law consulting, outsourcing, and local search engine optimization. The two are retailers of food and beverages but were included in the study because, along with retailing, they engage in logistics consulting (e.g. consulting on distribution in order to improve customer service or securing suppliers). The age of the selected companies is between 2 and 10 years, and the number of employees between 5 and 27. In regards to their client base, all of the company cases, without exception, have British and Bulgarian clients in the UK as well as UK-based clients from other nationalities. In addition, all of them except two companies stated that under 10% of their total clientele is located in the home country (Bulgaria).

The order of the cases has no other purpose than simplifying the analysis and maintaining the anonymity of the subjects. For the purpose of preserving anonymity and complying with the confidentiality and ethics agreements, financial data, the year of foundation and specific number of employees are not provided. This is not a restraint that could affect the quality of the research, as it is not the intention of the study to provide a basis for comparison in these particular aspects.

The degree of business affiliation to the home country is strong in all the cases despite the rather small number of customers coming from there. Thus, the business affiliation with the home country is represented by alternative factors (social capital, knowledge, suppliers etc.). All studied entrepreneurs stated that they are “affiliated” or “very affiliated” to their home country.

The observed overall knowledge intensity of the companies is predominantly high, a characteristic that coincides with the fact that all of the involved companies have declared in their company profiles that they engage in consulting operations.

3.3 Research Approach

According to Schutz (1962), it is the participants’ narratives that best represent the social reality explored by researchers. Therefore, this study scrutinizes the narratives produced by transnational entrepreneurs in order to build full understanding of the employed learning model that is believed to occur in the environment under consideration.

Following Rogoff’s (1995) recommendation to researchers studying learning environments, three layers have been located in the discourse and examined—personal (micro: the entrepreneur’s experience), interpersonal (meso: one-on-one communication and exchange) and community (macro: the diaspora interactions), for the purpose of getting a full grasp on the occurring dependencies. The study is based the ontological premise that realities are of a socially constructed nature. Consequently, the employed philosophical assumptions are of a constructionist nature. The constructionist epistemological stance asserts that human beings construct meaning based on their engagement with the realities in the social and physical environments (Crotty 1998).

3.4 Data Reduction and Analytical Approach

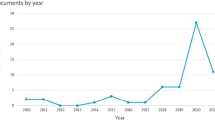

All interviews and field notes were transcribed and analyzed through narrative analysis. Following Corley and Gioia’s (2004) approach to data structure, the analysis was divided into three coding stages: delineating first-order concepts, second-order themes and aggregate dimensions (see Fig. 1).

In the first stage, open coding, we created first-order categories on the basis of raw data (quotes) from the interview material. Statements by the interviewees which described various events, actions, and perceptions in the evolution of their businesses were identified and commonalities in the narratives identified. These categories were initially coded by the first author, who had conducted the interviews. The other authors subsequently revisited these categories, verifying the fit between the quotes and the interpretations contained in the categories.

In the second stage—axial coding—we integrated the first-order categories into second-order themes, identifying patterns in the data which allowed us to isolate the processes made up by the various events and actions occurring in the development of the TEs’ businesses. In the final stage, we applied selective coding in order to aggregate the theoretical dimensions that emerged as fundamental for this study.

These coding stages facilitate constant data comparison, which reflects the abductive research process that this study employs. The abductive approach requires data and theoretical ideas to be intertwined, with the researchers moving back and forth between data and relevant strands of theory, continuously reinterpreting the data in the light of theory. This approach is particularly relevant here as it creates scientific accounts out of the social accounts of the entrepreneurs’ engagement in the environment (Blaikie 2000). This approach helped us to identify the relevance of the transactive memory and organizational learning constructs, which were not initially adopted at the outset of the field work.

4 Findings

In this section, we describe the entrepreneurs’ experiences in building their businesses in London, showing how the diaspora community facilitates this by helping the entrepreneurs recognize how valuable their specific knowledge about unique opportunities or resources in Bulgaria is to their customer, as well as to other members of the diaspora network. Additional representative quotes supporting the findings’ interpretation can be found in Table 3.

Moreover, supplementary representative quotes illustrating the assets stemming from the cases’ “Bulgarianness” and membership in a diaspora network are provided in Table 3. The table consists of quotes from each entrepreneur, which not only demonstrate the adopted cross-case analytical approach, but also provide insight on the nature of the accumulated case knowledge. Both Tables 3 and 4 support the arguments that follow in this section.

4.1 Embedding and Bridging

We view identity (and the way it is operationalized for the development of competitive advantage and business contacts) as a fluid but not directionless process (Watson and Harris 1999). For that reason, while the TEs studied here all form their identities in the context of ethnicity and the diaspora social system, they have different degrees of embeddedness and are thus at different stages of building their competitive advantage. Narrative analysis shed light on the TEs’ path to realizing identity-driven competitive advantage.

The processes in which TEs engage to leverage their assets of foreignness are made up of components corresponding to the second-order themes in Fig. 1. The initial activities (“trust building” and “integration with diaspora incumbents”) activate the later processes of knowledge acquisition and transfer (“distributed knowledge” and “knowledge transfer”) through which TEs build a portfolio of competencies and resources. As suggested by the label “distributed knowledge”, this process refers not only to obtaining new resources, but also realizing that resources and competencies could be extracted from the entrepreneur’s own transnational experiences and familiarity with the dual social field. The next stage not only highlights the importance of the dual social/business identity of TEs, but also shows how the actors have operationalised this dual identity as part of their business activities in terms of “signalling bridging opportunities” and “bridge building”.

After discussing their perspectives on the formation of a community of immigrants within the UK, the interviewed TEs were asked about the initiatives they realize within that community structure, and whether and how those initiatives influence their business operations.

“I am affiliated [to national roots/national identity] and I will always be. I am not trying to run away from my identity because this is who I really am. Furthermore, it is my home country and people from my country that basically developed my business. I would probably still work for somebody else if it were not my idea to make some profit on my compatriots’ needs and my familiarity with Bulgarian food and culture. Of course, it is easy for me to disregard all that as I now count on not only Bulgarian products and consumers, but it would be wrong. I could also say that it was only my own efforts that created the company; however, that would also be wrong. I have benefited a lot and I will always be very thankful” (Entrepreneur A).

This quote implies the value that personal identity and relatedness to the home country have at the early stages of a company’s emergence and development. The entrepreneur clearly emphasizes the importance of capitalizing on his closeness to the people, culture, and products of his home country. This is also evident in the discourse of other entrepreneurs who put even more emphasis on why community formation among immigrants within the UK is important for the ongoing development of their activities.

“I cannot detach from my home country. Not only in a personal way, but also in a professional way. If I detach then I will lose my positions, my contacts, and I will not be able to continue my business” (Entrepreneur C).

The recurrence in all of the cases of the relationship between ethnic and occupational affiliation points to the existence of factors that benefit entrepreneurs by preserving their social and cultural identity.

This social and cultural dimension forms the basis for connections that yield business benefits as well. Recurring testimony by the entrepreneurs suggests that being active in the diaspora community has strong business implications. Entrepreneur J sheds light on this by highlighting the knowledge integration benefits stemming from collaboration.

“We work closely with some Bulgarian business organizations that we have met here. […] That collaboration also allows us to benefit from each other’s knowledge without having the need to hire more personnel. Hiring people is good when productivity increases, but increasing the productivity without hiring extra people is even better as it increases our success rate” (Entrepreneur J).

The quote highlights how participation in diaspora organizations builds social ties, which can assist the TEs in the process of business formation and growth and product/service realization. The particular forms of assistance that have been observed include provision of information regarding prospects for sponsorship, a wide range of institutional and legal support functions in the host country (e.g., with import/export procedures), as well as other forms of knowledge transfer and, perhaps most importantly, introductions to new customers (see quotation 8.1 in Table 3). The symbiosis that occurs through the exchange of market-favored competencies evolves into a resource interdependency in which two or more companies share knowledge, technology or a service pool that allows for greater specialization of the individual companies and the achievement of long-term benefits. A long-term orientation seems prevalent and may be necessary for cooperation to take place. Particular phrases that suggest the reliance on relatedness include variations of cooperation, frequently (indicated repeated incidence of cooperation), and future, which indicate the entrepreneurs’ desire for continuation of the observed interdependence.

“The communication that we have in the community is the reason to cooperate frequently. In the long term, this brings positives for both sides” (Entrepreneur C).

The collected data suggest that the development of network relations embracing a wide range of business partners—both similar and diverse ones—is possible when founded on shared cultural belongingness, embodied in the diaspora organizations in whose orbit the TEs find themselves. This strong network-centered orientation accelerates the externalization of internal competencies and capabilities and their transfer to related parties.

“Most of them [diaspora members] are experts in doing business and they can help with direct advice and share stories [about] what has happened [to] a company engaged in a particular strategy. Moreover, they have many business contacts with people from various spheres, which can also benefit us as information does not flow directly. Discussing with members enhances referrals and linking to other parties, which creates a significant mechanism for transferring business ideas and facilitating problem solving” (Entrepreneur L).

This quote focuses on the factors expertise and bridging capabilities. The first factor is evident from multiple pointer phrases such as extremely experienced, achieved significant success, showed strengths and capabilities that the market has accepted, and experts. The second factor, bridging, is indicated by the phrases: share stories, provide direct advice, benefit us, discussing, enhances referrals, and linking to other parties. Both factors seem to be fundamental drivers of the close relationship between social ties and their utilization for business development purposes. Entrepreneur L implies that actors who have many business contacts in various spheres are regarded as important gatekeepers who bridge expertise through referrals.

Thus, participation in diaspora organizations builds social ties that can be employed in the process of business formation and growth and product/service realization. The link between social ties and their utilization for business development, revealed in the interviewees’ references to factors such as expertise and bridging capabilities, allows for the emergence of a novel competitive orientation, embraced by various transnational entrepreneurs, removing competition from the firm-to-firm level to the network level (i.e., communities of entrepreneurs, rather than individual firms, compete with each other), which gives the network a sort of incubator function.

Crucially, the Bulgarian entrepreneurs are able to leverage their distinctive cultural identity not only with the diaspora community incumbents, but also with British locals.

“I have brought locals to some culture-related events and performances organized by the Bulgarian embassy, this is a way of showing them who I really am. In a way, if you are trying to hide your background, that does not create any trust, and this will probably lead to being rejected by both your people and the new society. The integration in the foreign environment certainly goes though being upfront about your own culture and belongingness” (Entrepreneur G).

This quote shows the conviction of the entrepreneur that ethnic communities are useful for the integration of immigrants in the new environment. Rather than creating a ghetto for ethnic nationals for the purpose of preserving and isolating the national culture from the foreign one, diaspora communities can facilitate integration into the new environment, while upholding identity. As Table 2 shows, the customer base for all the companies includes both Bulgarian and UK nationals. It also shows that for all but one of the companies, the latter are the more numerous group of customers, demonstrating the importance of building bridges to that group of potential clients for development of the TEs’ businesses.

The example that best exemplifies this is that of a Bulgarian wine import company that works closely with Bulgarian competitors who share the common goal of improving the product’s acceptance in the host country environment.

“We are now trying to gain sufficient customer acceptance and that is the reason we work closely with other associations that aim at improving the acceptance of Bulgarian wine. This goal motivates us to cooperate with our major competitors, as we all feel that inserting the product in the foreign market is a key step before we unfold our sales potential” (Entrepreneur H).

The desired outcome of the emergent network collaboration is the greater acceptance of Bulgarian wine, which will result in reciprocated benefits that cannot be achieved through isolated activities. Pushing competition up to the network level builds reputation and establishes various contacts to different business spheres and social circles, which facilitates unfolding sales potential.

The next quote refers both to what one might call the liabilities of domesticity and the assets of foreignness, showing how the latter—again resulting from bridging opportunities available to TEs but not to native Londoners—can be used to leverage the inclusion of native British citizens in the team and thus facilitate building bridges into the host country environment, as well as between the host and home country environments.

“Many [British competitors] fail because they do not expect that a client company would prefer a much smaller marketing partner solely due to its complete familiarity with the two countries. We, as a team of educated professionals that consists of Brits and Bulgarians, are better positioned as intermediaries. This gives us the advantage to attract both British companies going to Bulgaria and Bulgarian companies coming to Britain. This has helped us to survive and gain momentum in our development” (Entrepreneur B).

This suggests that the TEs’ “advantage of Bulgarianness” is characterized by their ability to attract both British companies going to Bulgaria and Bulgarian companies coming to Britain. The observation that both British and Bulgarian players have both advantages and liabilities resulting from their country of origin, and that TEs can balance these in such a way as to maximize the strengths of both sides, is pervasive in the data and particularly highlighted in the following example:

“Native [English] consultancies have a better and stronger link to the British companies. On the other hand, the consultancies located in Bulgaria but operating here tend to have a better link to Bulgarian companies. Both sides are strong in some aspects and weak in another aspect. What I believe we do better than both, however, is relating both sides so that they can work together” (Entrepreneur C).

We would like to conclude our examination of the process of embedding by a brief remark about the temporal dimension of the process. The reader will note that in describing the process, we have referred a number of times to stages. The question may therefore arise whether there is a link between the progress achieved in the embedding process and the length of time a firm has been operating in the UK. Based on our analysis of the interview data, it is clear that while some entrepreneurs were able to benefit from the assets of their nationality earlier than others, this was not directly dependent on the age of the company but rather on their proactiveness within the network in realizing the first-order categories (Fig. 1), and in particular, “understanding benefits of knowledge sharing”. Different firms did this at different speeds, so there was no simple, linear relationship between the passage of time and the achievement of certain milestones in the embedding process.

4.2 The Diaspora Community’s Distributed Knowledge Base

The diaspora functions as a community of practice that connects entrepreneurial opportunity seekers to the object of their interest. Communities of practice serve as an apparatus that, when empowered by TEs’ bridging capability (i.e. the ability to connect different parties), facilitates members’ attempts to develop or improve capabilities for the purpose of achieving greater competitiveness in the market. Communities of practice within the diaspora not only engender reciprocity, but also cultivate links to a wide range of producers, suppliers, business professionals and potential customers. Transnational entrepreneurs in the diaspora community are able to capitalize on their transactive memory—i.e., the apparatus through which prior global experiences influence present and future actions—thus linking foreignness to an enriched exploration of opportunities. And it is the collective resource of transactive memory that makes a community of practice a community.

Some of the quotes in Table 3 provide a sort of window through which we can catch some glimpses of the processes in which the collective knowledge resource of the TEs’ transactive memory manifests itself. Entrepreneur F, for example, refers to brainstorming and idea generation. Entrepreneur D refers to discussions in which ideas and suggestions are sought. Entrepreneur A refers to the role of mentors in this process. The picture that emerges is one of goal-oriented discussions about problems the TEs are currently facing, in which they engage in give and take that includes more senior members of the community, playing a guiding role.

This also provides insight into how network interactions within the diaspora yield novel applicable ideas (see quote 18.1 in Table 3) representing not only a transfer of capabilities among network actors, but also the recombination and creation of new ones. This involves a pooling of resources, as shown in the following example.

“We cannot afford to keep a person who we need only twice a year. Moreover, the people we are looking for are experts in their fields and they are expensive. Expertise has always been highly valued so we purchase only part of the time of that specialist and build up the rest of the project based on the ideas and information we have acquired or that we possess in-house. Such free agent consultants often work for four or even five companies, advising them. It is inefficient, too expensive for a single company to afford such high ranked specialists, but we still benefit from the innovative thinking of such acknowledged experts rather than competing with them. In that way we can provide our clients with solutions for their business, solutions that would have cost them a fortune if they were to hire all the narrow experts that we communicate with” (Entrepreneur I).

The entrepreneur reveals how the sharing of contacts (e.g., consultants) and their competencies by diaspora companies supports their businesses. The diffusion and the efficient management of contacts among diaspora members leads not only to the exchange of market-favored competencies, but also to the development of new ones when linked to in-house resources.

Another excerpt further exemplifies the benefits that stem from the communication, diffusion, integration, and systemization of knowledge within the diaspora network.

“The collaboration within the diaspora and the interaction with other members help me not only to acquire high quality new knowledge at a fraction of its value, but also to achieve better use of the available knowledge. New use of already existing information is as valuable as new information, with the only difference that I am less dependent on others, as I carry it with me when crossing borders. […] For that reason, it is important to link with others that have a different point of view and might enrich the idea generation process by either spotting a new application of my knowledge or helping me to build on what I have picked up” (Entrepreneur D).

This quote suggests that the systematization of knowledge may lead to knowledge innovation with the shared resources at hand. Foreign entrepreneurs must be able to combine the unique “foreign” assets that they bring to the host country (i.e., bridging capabilities and as the group’s transactive memory) with the benefits of the social network. The creative recombination of resources enables entrepreneurs to find new applications of their resources and to ultimately better relate to the host-country market.

5 Discussion and Conclusions

We have seen that diaspora networks provide transnational entrepreneurs with a unique organizational infrastructure that supports, and helps shape, the way they develop strategies for the management, combination and utilization of resources (cf. Stoyanov et al. 2017, on transnational entrepreneurs’ resource orchestration). The diaspora community serves as a learning context that turns foreignness into an asset by providing TEs with access to a collective resource we refer to (following Argote 2013) as transactive memory.

Transactive memory as a distributed body of collective knowledge is indicated in the quotes by entrepreneurs J and C about the knowledge they gain from other Bulgarian entrepreneurs, referring to “collaboration” in which they “benefit from each other’s knowledge” (Entrepreneur J), as well as to “communication” within a “community” and cooperation that occurs “frequently” (Entrepreneur C). Like the TEs discussed by Boissevain et al. (1990), those we studied sought each other out in order to gain knowledge about legal and market conditions in the London setting, as well as information about, and contacts with, customers. In addition to such information, however, we saw them sharing managerial knowledge that could enhance their capabilities (see Entrepreneur L’s remarks about “transferring business ideas and facilitating problem solving”). It is clear that the distributed knowledge in this system goes well beyond various forms of explicit information that can be easily communicated, about markets and regulations, etc., to include tacit, experiential knowledge, sometimes shared in brainstorming sessions (Entrepreneur A even refers to “mentors”). In fact, it is this latter form of knowledge that probably constitutes the most valuable form of knowledge in the system (consistently with Kogut and Zander 1992). One of the benefits accruing to the TEs from this is the way they can utilize the network-related assets associated with their national identity—i.e., their “Bulgarianness”—to draw valid inferences from old experiences and improve their interaction with the host-country business environment. Their shared “Bulgarianness” allows for social interaction and the development of personal relations among members, stimulating the shift of knowledge from individuals to the group that constitutes transactive memory. The strong network orientation accelerates the externalization of internal competencies, capabilities and ideas for market opportunities. Once exchanged, the knowledge and skills open opportunities for the development of new businesses or the development of new practices that lead to economic gains. It is difficult for competitors to attain or imitate these specific organizational benefits due to the complex social attributes on which embeddedness is built, and this means that organizational advantages become rooted in businesses and are difficult for others to imitate due to their social attributes (Nelson and Winter 1982; Grant 1996; Spender 1996). The low levels of imitability make these resources a source of effective and long-term competitive advantage, which motivates entrepreneurs to seek external knowledge and use it for increasing their ventures’ capabilities.

Another benefit of “Bulgarianness”, when leveraged effectively, is—almost paradoxically—the ability it gives the TEs to forge links with potential partners from the host country. As noted above, Moore (2016a, b) has described how the ambiguities that characterize the identity of an individual TE may enable that entrepreneur to establish connections with members of various communities. Our findings additionally demonstrate the collective nature of the resources that underlie the TEs’ ethnic identity, by showing how Bulgarian entrepreneurs in London could make or deepen connections with British business partners by introducing them to Bulgarian culture at events sponsored by diaspora organizations. The quoted entrepreneur explicitly refers to the building of trust by familiarizing British partners with his cultural identity, thus “showing them who I really am”. His foreignness itself, when construed as “Bulgarianness”, is used to overcome the liability with which it is associated—that of being excluded from host country networks (Johanson and Vahlne 2009). This indication of the importance of culture for the development of embeddedness, in turn, points to the importance of the assets of foreignness for the transfer of tacit knowledge which gives rise to trust and enables the TEs to gain legitimacy in the host country environment.

As a result, we argue for a different approach to the foreignness concept altogether, by defining actors in terms of what groups they belong to, as opposed to what they do not belong to. And so the home country, rather than foreignness in the host country, becomes crucial for the entrepreneurs studied here; rather than departing from the socio-cultural norms of the home country (Witt and Lewin 2007), they use them as a stepping stone to accessing non-local institutional knowledge. Ostgaard and Birley (1994) argue that the personal network of an entrepreneur is the most crucial resource for a young company’s survival because it gives the entrepreneur the opportunity to draw upon it in the early stages.

By connecting different parties, communities of practice facilitate TEs’ attempts to develop or improve capabilities for the purpose of achieving higher competitiveness in the market. The recombination among network actors not only disseminates capabilities, but also results in the creation of new ones. In this way, the entrepreneurs manage to form autonomous specialization competencies. Thus, by combining the benefits extracted from their social networks with their unique foreign’ assets that they bring to the host country (i.e., transactive memory and bridging capabilities), TEs can unfold their business potential in host countries.

6 Contributions

This study presents evidence regarding the assets stemming from foreignness. Our findings are in line with those of studies showing that social capital—companies’ possession of the organizational competences to achieve interdependence with other parties—is directly related to the formation and acquisition of knowledge (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998; Tsai and Ghoshal 1998; Lorenzoni and Lipparini 1999; Yli-Renko et al. 2001), and that ethnic identities and networks can serve as sources of advantage for ethnic/diaspora entrepreneurs (Auster and Aldrich 1984; Waldinger et al. 1990; Elo 2015). The new insight added by our analysis concerns the question of how access to a diaspora network enables a special class of foreign actors—transnationals—to develop organizational capabilities that would have otherwise remained unrecognized or underdeveloped.

The first contribution that this paper makes is to point out that by shifting the focus from the negative quality of “foreignness” (“not one of us”) to the positive quality of “Bulgarianness” (an “us” out there somewhere that this group of people can identify with), we can explain how what is often considered a liability can also be transformed into asset when the foreigner in question embeds her-/himself in a community (in this case, a diaspora network). The assets we observed included access to the collective resources of the network and capabilities for bridging two markets (home and host), which give a niche quality to the TEs’ business activities. By doing so, we present evidence that challenges the tendency to characterize actors in terms of what they are not (or what groups they do not belong to) as opposed to what they are or what they do belong to.

The second contribution that this paper makes is showing that the links between learning and knowledge utilization are contingent on the network context. The diaspora network is the locus of one of the most important assets of foreignness available to the TEs—that of the members’ transactive memory, their collective knowledge base. By nurturing social as opposed to solitary learning, the diaspora network allows entrepreneurs to enter unpredictable and unintended situations in an authentic social context, which supports the actors’ improvisation upon best diaspora entrepreneurial practices for the sake of new knowledge creation.

7 Limitations and Future Research

Later studies might explore different transnational settings, including diasporic and non-diasporic business circles, to test the conclusions of the current paper and cross-validate the identified assets of foreignness. This should shed additional light on the circumstances under which foreignness is an asset rather a liability. Currently, replicability is constrained by the limited sample and the nature of the employed qualitative methodology. The natural setting in which fieldwork occurs impedes control over external factors, which may further hinder replication. Future research may address this limitation by testing the theories proposed here in different geographic and social settings, using larger, more representative samples and quantitative methods.

In addition, future research may consider the likelihood that a diaspora’s ability to facilitate the conversion of liabilities of foreignness into assets may vary depending on the specific sociocultural characteristics of the observed communities within the transnational space. Differences in attitudes, ethnic identities and values, kinship structures, rituals and reputation may lead to variances across communities in terms of their members’ abilities to develop capabilities and integrate knowledge from both home and host country environments, making the mapping cross-cultural differences and investigating how they influence the conversion of liabilities within a transnational network an interesting area for future work.

References

Ahuja, G., Polidoro, F., & Mitchell, W. (2009). Structural homophily or social asymmetry? The formation of alliances by poorly embedded firms. Strategic Management Journal, 30(9), 941–958.

Argote, L. (2013). Organizational learning: Creating, retaining, and transferring knowledge (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

Argote, L. (2015). An opportunity for mutual learning between organizational learning and global strategy researchers: transactive memory systems. Global Strategy Journal, 5(2), 198–203.

Auster, E., & Aldrich, H. (1984). Small business vulnerability, ethnic enclaves and ethnic enterprise. In R. Ward & R. Jenkins (Eds.), Ethnic communities in business: Strategies for economic survival (pp. 39–54). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Austin, J. (2003). Transactive memory in organizational groups: The effects of content, consensus, specialization, and accuracy in group performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 866–878.

Baik, B., Kang, J., Kim, J., & Lee, J. (2013). The liability of foreignness in international equity investments: Evidence from the US stock market. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(4), 391–411.

Basu, A. (2004). Entrepreneurial aspirations among family business owners: An analysis of ethnic business owners in the UK. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 10(1/2), 12–33.

Becerra-Fernandez, I., & Sabherwal, R. (2008). Individual, group, and organizational learning: A knowledge management perspective. In I. Becerra-Fernandez & D. Leidner (Eds.), Knowledge management: An evolutionary view. Advances in Management Information systems (Vol. 12, pp. 21–33). New York: M.E. Sharpe.

Bell, J., McNaughton, R., Young, S., & Crick, D. (2003). Towards an integrative model of small firm internationalisation. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 1(4), 339–362.

Birley, S. (1985). The role of networks in the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 1(1), 107–117.

Blaikie, N. (2000). Designing social research. The logic of anticipation. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Boissevain, J., Blaschke, J., Grotenbreg, H., Joseph, I., Light, I., Sway, M., et al. (1990). Ethnic Entrepreneurs and Ethnic Strategies. In R. Waldinger, H. Aldrich, R. Ward, et al. (Eds.), Ethnic entrepreneurs: Immigrant business in industrial societies (pp. 131–156). London: Sage.

Centre for Entrepreneurs and DueDil. (2014). Migrant Entrepreneurs: Building Our Businesses, Creating Our Jobs. London. http://www.creatingourjobs.org/data/MigrantEntrepreneursWEB.pdf. Accessed 18 Nov 2015.

Chen, W., & Tan, J. (2009). understanding transnational entrepreneurship through a network lens: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(5), 1079–1091.

Chetty, S., & Holm, D. B. (2000). Internationalisation of small to medium-sized manufacturing firms: A network approach. International Business Review, 9(1), 77–93.

Chung, H. F. L., & Enderwick, P. (2001). An investigation of market entry strategy selection: Exporting vs foreign direct investment modes—a home-host country scenario. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 18(4), 443–460.

Corley, K., & Gioia, D. (2004). Identity ambiguity and change in the wake of a corporate spin-off. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49(2), 173–208.

Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. London: Sage.

Denk, N., Kaufmann, L., & Roesch, J. (2012). Liabilities of foreignness revisited: A review of contemporary studies and recommendations for future research. Journal of International Management, 18(4), 322–334.

Dimitratos, P., Buck, T., Fletcher, M., & Li, N. (2016). The motivation of international entrepreneurship: The case of Chinese transnational entrepreneurs. International Business Review, 25(5), 1103–1113.

Drori, I., Honig, B., & Wright, M. (2009). Transnational entrepreneurship: An emergent field of study. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 33(5), 1001–1022.

Dunning, J. H. (1993). Multinational enterprises and the global economy. Wokingham, Berkshire: Addison Wesley.

Dyer, J., & Singh, H. (1998). The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 660–679.

Eden, L., & Miller, S. (2004). Distance matters: Liability of foreignness, institutional distance and ownership strategy. Advances in International Management, 16, 187–221.

Elo, M. (2015). Diaspora networks in international business: A review on an emerging stream of research. In J. Larimo, N. Nummela, & T. Mainela (Eds.), Handbook on international alliance and network research (pp. 13–41). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Fairlie, R. W., & Meyer, B. D. (1996). Ethnic and racial self-employment differences and possible explanations. Journal of Human Resources, 31(4), 757–793.

Fernhaber, S.A., McDougall, P.P., & Oviatt, B.M. (2007). Exploring the role of industry structure in new venture internationalization. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(4), 517–542.

Fletcher, M., Harris, S., & Richey, R. (2013). Internationalization knowledge: What, why, where, and when. Journal of International Marketing, 21(3), 47–71.

Grant, R. M. (1996). Prospering in dynamically-competitive environments: Organizational capability as knowledge integration. Organization Science, 7(4), 375–387.

Gulati, R. (1995). Does familiarity breed trust? The implications of repeated ties for contractual choice in alliances. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 85–112.

Hymer, S. (1976). International operations of national firms: A study of foreign direct investment. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Ilhan-Nas, T., Sahin, K., & Cilingir, Z. (2011). International ethnic entrepreneurship: Antecedents, outcomes and environmental context. International Business Review, 20(6), 614–626.

Joardar, A., Kostova, T., & Wu, S. (2014). Expanding international business research on foreignness. Management Research Review, 37(12), 1018–1025.

Joardar, A., & Wu, S. (2011). Examining the dual forces of individual entrepreneurial orientation and liability of foreignness on international entrepreneurs. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 28(3), 328–340.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. (2009). The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(9), 1411–1431.

Jun, S., Gentry, J. W., & Hyun, Y. J. (2001). Cultural adaptation of business expatriates in the host market. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(2), 369–377.

Keupp, M., & Gassmann, O. (2009). The past and the future of international entrepreneurship: A review and suggestions for developing the field. Journal of Management, 35(3), 600–633.

Kloosterman, R., & Rath, J. (2001). Immigrant entrepreneurs in advanced economies: mixed embeddedness further explored. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 27(2), 189–201.

Knight, G.A., & Cavusgil, S.T. (2004). Innovation, organizational capabilities, and the born-global firm. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2), 124–141.

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science, 3(3), 383–397.

Lane, P., & Lubatkin, M. (1998). Relative absorptive capacity and interorganizational learning. Strategic Management Journal, 19(5), 461–477.

Larsson, R., Bengtsson, L., Henriksson, K., et al. (1998). The interorganizational learning dilemma: Collective knowledge development in strategic alliances. Organization Science, 9(3), 285–305.

Levitt, B., & March, J. G. (1988). Organizational learning. Annual Review of Sociology, 14, 319–340.

Lewis, K. (2004). Knowledge and performance in knowledge worker teams: A longitudinal study of transactive memory systems. Management Science, 50(11), 1519–1533.

Lewis, K., & Herndon, B. (2011). Transactive memory systems: Current issues and future research directions. Organization Science, 22(5), 1254–1265.

Lord, M., & Ranft, A. (2000). Organizational learning about new international markets: Exploring the internal transfer of local market knowledge. Journal of International Business Studies, 31(4), 573–589.

Lorenzoni, G., & Lipparini, A. (1999). The leveraging of interfirm relationships as a distinctive organizational capability: A longitudinal study. Strategic Management Journal, 20(4), 317–338.

Lu, J.W., & Beamish, P.W. (2001). The internationalization and performance of SMEs. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6–7), 565–586.

Madsen, T.K., & Servais, P. (1997). The internationalization of born globals: an evolutionary process? International Business Review, 6(6), 561–583.

Moore, F. (2016a). City of Sojourners versus City of Settlers: Transnationalism, location and identity among Taiwanese professionals in London and Toronto. Global Networks, 16(3), 372–390.

Moore, F. (2016b). Flexible identities and cross-border knowledge networking. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 12(4), 318–330.

Muzychenko, O. (2008). Cross-cultural entrepreneurial competence in identifying international business opportunities. European Management Journal, 26(6), 366–377.

Nachum, L. (2003). Liability of foreignness in global competition? Financial service affiliates in the City of London. Strategic Management Journal, 24(12), 1187–1208.

Nachum, L. (2010a). Foreignness, multinationality and inter-organizational relationships. Strategic Organization, 8(3), 230–254.

Nachum, L. (2010b). When is foreignness an asset or a liability? Explaining the performance differential between foreign and local firms. Journal of Management, 36(3), 714–739.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–266.

Nelson, R., & Winter, S. (1982). An evolutionary theory of economic change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nonaka, I., & von Krogh, G. (2009). Tacit knowledge and knowledge conversion: Controversy and advancement in organizational knowledge creation theory. Organization Science, 20(3), 635–652.

Orr, R., & Scott, W. (2008). Institutional exceptions on global projects: A process model. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(4), 562–588.

Ostgaard, T., & Birley, S. (1994). Personal networks and firm competitive strategy: A strategic or coincidental match. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(4), 281–305.

Penrose, E. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Petersen, B., & Pedersen, T. (2002). Coping with liability of foreignness: Different learning engagements of entrant firms. Journal of International Management, 8(3), 339–350.

Podolny, J. (2001). Networks as pipes and prisms of the market. American Journal of Sociology, 107(1), 33–60.

Portes, A., Haller, W., & Guarnizo, L. (2002). Transnational entrepreneurs: An alternative form of immigrant economic adaptation. American Sociological Review, 67(2), 278–298.

Radhakrishnan, R. (2003). Ethnicity in an age of diaspora. In J. E. Braziel & A. Mannur (Eds.), Theorizing diaspora (pp. 119–131). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Rangan, S., & Drummond, A. (2004). Explaining outcomes in competition among foreign multinationals in a focal host market. Strategic Management Journal, 25(3), 285–293.

Rauch, J. E. (2001). Business and social networks in international trade. Journal of Economic Literature, XXXIX, 1177–1203.