Abstract

It is often argued that words have complex internal structure in terms of their morphology, phonology, and semantics. On the surface, Armenian compounds present a bracketing paradox between their morphological and phonological structure. I argue that this bracketing paradox simultaneously references endocentricity, strata, and prosody. I use Armenian as a case study to argue for the use of cyclic approaches to bracketing paradoxes over the more common counter-cyclic approaches. I analyze the bracketing paradox using cyclic Head-Operations (Hoeksema 1985) and Prosodic Phonology (Nespor and Vogel 1986), specifically the Prosodic Stem (Downing 1999a). I argue that the interaction between the bracketing paradox and the rest of compound phonology requires the use of stratal levels and cyclicity. I argue that counter-cyclic approaches like Morphological Merger (Marantz 1988) or Morphological Rebracketing (Sproat 1985) are inadequate because they make incorrect predictions about Armenian phonology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

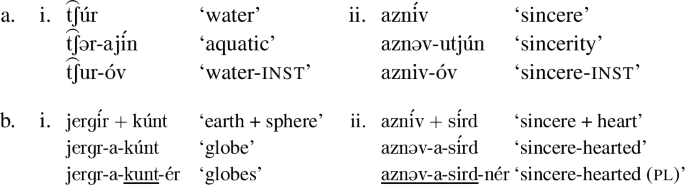

Data is collected from the various sources cited in the bibliography, Wiktionary, and my own native (Western) judgments. Glosses are taken from Armenian-English dictionaries if available, otherwise my own translation. Data is transcribed in IPA. For Western Armenian, aspiration is not contrastive and is not marked. I transcribe the tap as <r>, uvular fricatives

as <

as < >, and the lax mid-vowels

>, and the lax mid-vowels  are transcribed as <

are transcribed as < >. Armenian citations are Romanized based on the ISO 9985 transliteration system.

>. Armenian citations are Romanized based on the ISO 9985 transliteration system.Endocentric compounds are right-headed in Armenian; left-headed compounds are judged as ungrammatical (Karapetyan 2016, 36).

For space, I don’t discuss some solutions that developed in non-Chomskyan frameworks, e.g., Autolexical Theory (Chelliah 1995), CG (Chae 1990, 1993), CCG (Bozsahin 1999), HPSG (Crysmann 1999; Müller 2003), LFG (Kim 1991, 1992), Dependency Grammars (Gross 2011a,b), a.o. I also don’t discuss work that focuses on paradoxes between the morphological, syntactic, and semantic representations, such as in the phrases transformational grammarian and beautiful dancer (Williams 1981; Strauss 1982; Sadock 1985; Spencer 1988; Beard 1991; Becker 1993; Fukushima 1999, 2015, 2014; Ackema and Neeleman 2004; Belk 2019).

Most compounds consist of only two stems but there are compounds which have three or more stems:

‘small + light + picture’ →

‘small + light + picture’ →  ‘micro-photograph’. A linking vowel is used between each stem. These large compounds are rarely used and mostly restricted to higher registers. Data on their phonology is limited and I do not discuss them.

‘micro-photograph’. A linking vowel is used between each stem. These large compounds are rarely used and mostly restricted to higher registers. Data on their phonology is limited and I do not discuss them.In (5b-iii), the derivational suffix modifies the meaning of the entire compound, not just the second stem. In fact, there is no free-standing word *

.

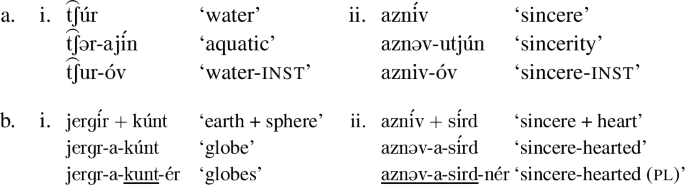

.In Eastern Armenian, V-initial inflection can cause the overapplication of destressed high vowel reduction:

‘waters’. I argue this is because of prosodic misalignment (Dolatian 2020a,b)). The same behavior extends to compounds, especially endocentric compounds:

‘waters’. I argue this is because of prosodic misalignment (Dolatian 2020a,b)). The same behavior extends to compounds, especially endocentric compounds:  ‘rain-waters’. The derivation above is just for Western Armenian. There are also fossilized rules of destressed e-to-i reduction and destressed ja-to-e reduction. These rules apply in some derivatives:

‘rain-waters’. The derivation above is just for Western Armenian. There are also fossilized rules of destressed e-to-i reduction and destressed ja-to-e reduction. These rules apply in some derivatives:  ‘love’ vs.

‘love’ vs.  ‘affectionate’,

‘affectionate’,  ‘apostle vs.

‘apostle vs.  ‘apostolic’. They do not apply in not inflection:

‘apostolic’. They do not apply in not inflection:  ‘love-inst’,

‘love-inst’,  ‘apostle-inst’. Both rules apply in compounding:

‘apostle-inst’. Both rules apply in compounding:  for

for  ‘love-letter’,

‘love-letter’,  ‘manner’ for

‘manner’ for  ‘apostle-like’.

‘apostle-like’.Before derivational suffixes, some rare repair rules are glide formation for i (i→,j), glide epenthesis for i and u, and vowel deletion for u. Before inflectional suffixes, Eastern Armenian allows vowel deletion for i and glide fortition for u. But these rules are much less common than glide epenthesis.

The allomorphy does not optimize phonological well-formedness. The only trace of optimization are CVCC bases which end in a rising-sonority cluster (Vaux 2003; Macak 2016). These clusters optionally take an excrescent or epenthetic schwa:

‘small’. Their plural can be bisyllabic with -er:

‘small’. Their plural can be bisyllabic with -er:  , or trisyllabic with -ner:

, or trisyllabic with -ner:  . The choice varies by dialect, speaker, and item. I put these cases aside. A few other morphemes also show suppletion based on syllable count, e.g. the indicative prefix (Vaux 1998) and possessive plurals (Arregi et al. 2013; Wolf 2013). None of these processes reference stress-assignment. Macak (2016) argues that they reference unstressed feet.

. The choice varies by dialect, speaker, and item. I put these cases aside. A few other morphemes also show suppletion based on syllable count, e.g. the indicative prefix (Vaux 1998) and possessive plurals (Arregi et al. 2013; Wolf 2013). None of these processes reference stress-assignment. Macak (2016) argues that they reference unstressed feet.I assume a simple morphological model for compounds (Selkirk 1982). In the morphological representation, I omit the linking vowel. I assume it is a semantically empty morph (Aronoff 1994; Ralli 2008) which is added during phonological spell-out in PF as a dissociated morpheme (Oltra-Massuet 1999; Tat 2013; Embick 2015). In the prosodic representation, I omit feet. In §6, I show that the two types of compounds have different prosodic constituencies below the PWord-level.

Free-standing verbs consist of a root followed a theme vowel -e,-i,-a and tense/agreement marking such as the infinitival -l:

‘to work’. Stem1 can be an infinitival verb or bound verbal root. In these compounds, Stem1 is verbal because the compound is interpreted as involving the activity of Stem1. These compounds can be translated with English gerunds.

‘to work’. Stem1 can be an infinitival verb or bound verbal root. In these compounds, Stem1 is verbal because the compound is interpreted as involving the activity of Stem1. These compounds can be translated with English gerunds.This figure is for deverbal compounds where Stem1 is a noun. This figure is larger if we include other categories for Stem1.

Speaker judgments vary on how to pluralize these compounds. I speculate that morphological ambiguity may play a role. In many of these adjectival compounds, Stem2 could be parsed an adjective or a verbal root:

‘dense’ vs.

‘dense’ vs.  ‘\(\sqrt{dense}\)’ in

‘\(\sqrt{dense}\)’ in  ‘to be dense’. An adjectival reading would make the compound hyponymic and take a paradoxical plural:

‘to be dense’. An adjectival reading would make the compound hyponymic and take a paradoxical plural:  xid-er, while a verbal parse would make the compound be non-hyponymic and take a transparent plural: derev-a-xid-ner. Here, the verb would be interpreted as an intransitive inchoative. I suspect that the deverbal reading is generally dominant.

xid-er, while a verbal parse would make the compound be non-hyponymic and take a transparent plural: derev-a-xid-ner. Here, the verb would be interpreted as an intransitive inchoative. I suspect that the deverbal reading is generally dominant.These judgments are my own and those of other Armenian speakers consulted.

I could not find an exocentric compound where Stem2 is

‘man’.

‘man’.There is evidence that compounds in Classical Armenian likewise displayed head-marking inflection. Classical Armenian did not have phonologically-conditioned suppletion for the plural, but it had many declension classes. These classes used different case suffixes. Compounds tended to inherit the class of their head Stem2 when endocentric (Olsen 2011).

I have reformulated the realization rule (27b) so that it can encode the intuition behind a head-operation. Formally, in Categorial Morphology (Hoeksema 1985), an inflectional process F is a head-operation if when given a morphologically complex input W = XY where Y is the head of W, then the output of F(Z) is XF(Y).

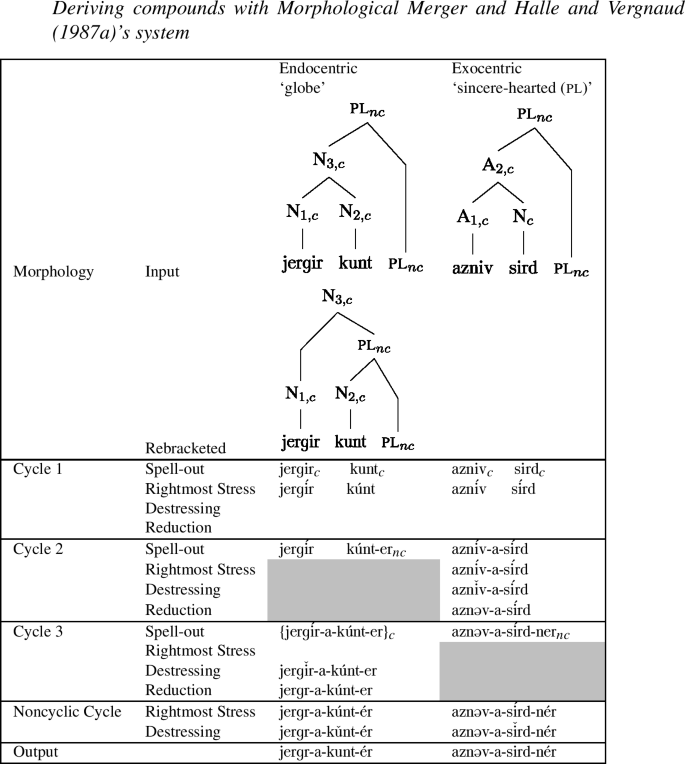

Using cyclically created autosegmental planes (Halle and Vergnaud 1987a) is also inadequate because it would not distinguish exocentric and endocentric compounds because both are cyclically formed and have identical stress planes (cf. a similar problem noted by Cohn 1989). Though in the Appendix, I show that counter-cyclically created planes don’t have this problem.

In this paper, I only discuss prosodically-conditioned variation. There is limited variation based on generation, dialect, semantic shift, semantic opacity, metaphoricity, animacy, loanwords, grammaticalization, lexicalization, and frequency (Sargsyan 1979, 1987; Marowt’yan 2003; Avetisyan 2007, 43). All relevant data and research are unfortunately only available in Armenian.

Although the linking vowel is generally absent before V-initial second-stems, there are some exceptions in recent borrowings and calques (Ēloyan 1972, 81). Another common exception is the superlative prefix

which usually takes the linking-vowel even before V-initial bases:

which usually takes the linking-vowel even before V-initial bases:  ‘just’ vs.

‘just’ vs.  ‘most just’ (Ēloyan 1972:80; Xačatryan 1988:68; among others).

‘most just’ (Ēloyan 1972:80; Xačatryan 1988:68; among others).An alternative is to let p stay unlabelled, i.e., the morphological structure is cyclically mapped to unlabelled prosodic constituents. Unlabelled prosodic constituents have been proposed before for the recursive mapping of phrasal cycles to gradient and relative prosodic structure (Wagner 2005, 2010). However, this alternative only recapitulates the problem of not having a label for p.

In compounds, there are conflicting impressionistic reports of secondary stress on the linking vowel (Margaryan 1997, 76):

‘air-ship-station (=airport)’, or the first syllable of Stem2 (T’oxmaxyan 1971, 63, 1983, 74). These reports are restricted to mostly tri-stem compounds, and are not acoustically supported (Toparlak 2019).

‘air-ship-station (=airport)’, or the first syllable of Stem2 (T’oxmaxyan 1971, 63, 1983, 74). These reports are restricted to mostly tri-stem compounds, and are not acoustically supported (Toparlak 2019).Besides the empirical problem of secondary stress, there is relatively little positive evidence for feet in Armenian. Primary stress in Armenian is final, cued by pitch (Athanasopoulou et al. 2017), non-iterative, and shows a hammock pattern with initial secondary stress. Because of these properties, Armenian has been argued to be footless (DeLisi 2015); its prosody has been modeled with just the metrical grid (Gordon 2002). French and Turkish have similar stress patterns, and they have also been argued to be footless (Özçelik 2017).

The above derivation is serial, however the prosodic mapping can be equivalently formalized with parallelist constraints, such as by adapting constraints from Match theory (Selkirk 2011) and Wrap theory (Truckenbrodt 1999) for stems. We would need a specialized constraint MatchEndo that requires that semantic heads are parsed to PStems. The output constraint *\((\sigma )_{s}( \sigma )_{s}\) bans a string of a monosyllabic PStems. Recursive structures would be blocked by a constraint NonRec. I do not flesh out these constraints; see Dolatian (2020b) for a partial illusrtation.

Morphological evidence for the separation of inflection from a root’s phase-cycle is that regular inflection does not trigger root suppletion. The closest case of suppletion is irregular inflection which also triggers reduction (Dolatian 2020a).

Halle and Vergnaud (1987a) assume a non-interactionist system whereby all morphological processes precede phonological processes. This means that they have problems in defining phonologically-conditioned allomorphy (Hargus 1993), e.g., the Armenian plural suffix. I set this problem aside for illustration.

It is possible that the SCC could be replaced with Shwayder (2015)’s ‘phonocyclic buffer’. The phonocyclic buffer is a diacritically determined linear span of morphemes for cyclic phonological processes. When combined with Morphological Merger, the plural suffix would get counter-cyclically spelled-out but it would not enter the buffer. The plural would latter undergo the post-cyclic rule of stress shift. In this way, the buffer lets us separate between the domain of cyclic processes and the domain of allomorphy (cf. §2.2). I leave exploring the use of this phonocyclic buffer to future work.

References

Abeġyan, M. (1933). Hayoc’ lezvi taġačap’owt’yown metri [Metrics of the Armenian language]. Yerevan: Haykakan SSH Gitowt’yownneri Akademiayi Hratarakčowt’yown.

Ackema, P., & Neeleman, A. (2004). Beyond morphology: Interface conditions on word formation. Oxford Studies in Theoretical Linguistics: Vol. 6. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Allen, M. R. (1979). Morphological investigations. Ph.D. thesis, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT.

Andreou, M. (2014). Headedness in word formation and lexical semantics: Evidence from Italiot and Cypriot. Ph.D. thesis, University of Patras, Patras, Greece.

Aronoff, M. (1988). Head operations and strata in reduplication: A linear treatment. In G. Booij & J. van Marle (Eds.), Yearbook of morphology (Vol. 1, pp. 1–15). Dordrecht: Foris.

Aronoff, M. (1994). Morphology by itself: Stems and inflectional classes. Linguistic inquiry monographs: Vol. 22. London/Cambridge: MIT Press.

Aronoff, M., & Sridhar, S. N. (1983). Morphological levels in English and Kannada, or atarizing Reagan. In J. F. Richardson, M. Marks, & A. Chukerman (Eds.), Papers from the Parasession on the interplay of phonology, morphology, and syntax (pp. 3–16). Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Arregi, K., Myler, N., & Vaux, B. (2013). Number marking in Western Armenian: A non-argument for outwardly-sensitive phonologically conditioned allomorphy. In 87th Linguistic Society of America annual meeting, Boston. Available online at https://works.bepress.com/bert_vaux/4/. Accessed 1 July 2019.

Athanasopoulou, A., Vogel, I., & Dolatian, H. (2017). Acoustic properties of canonical and non-canonical stress in French, Turkish, Armenian and Brazilian Portuguese. In Proceedings of Interspeech 2017 (pp. 1398–1402).

Avetisyan, Y. S. (2007). Arewelahayereni ew arewmtahayereni zowgadrakan k’erakanowt’yown [Comparative grammar of Eastern and Western Armenian]. Yerevan: Yerevani petakan hamalsaran.

Beard, R. (1991). Decompositional composition: The semantics of scope ambiguities and ‘bracketing paradoxes’. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 9(2), 195–229.

Becker, T. (1993). Back-formation, cross-formation, and ‘bracketing paradoxes’ in paradigmatic morphology. In G. Booij & J. v. Marle (Eds.), Yearbook of morphology 1993 (pp. 1–25). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Belk, Z. (2019). LF bracketing paradoxes: A new account. Syntax, 22(1), 24–65.

Bennett, R. (2018). Recursive prosodic words in Kaqchikel (Mayan). Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics, 3(1).

Bermúdez-Otero, R. (2008). Lexical Phonology crippled by the legacy of SPE. http://www.bermudez-otero.com/lexphon.pdf.

Bonet, E., Cheng, Lai-Shen, L., Downing, L. J., & Mascaró, J. (2019). (In) direct Reference in the Phonology-Syntax Interface under Phase Theory: A Response to “Modular PIC” (D’Alessandro and Scheer 2015). Linguistic Inquiry, 50(4), 751–777.

Bobaljik, J., & Wurmbrand, S. (2013) Suspension across domains. See Matushansky and Marantz (2013), pp. 185–198.

Booij, G. E. (1996). Cliticization as prosodic integration: The case of Dutch. The Linguistic Review, 13, 219.

Booij, G., & Lieber, R. (1993). On the simultaneity of morphological and prosodic structure. See Hargus and Kaisse (1993), pp. 23–44.

Booij, G., & Rubach, J. (1984). Morphological and prosodic domains in lexical phonology. Phonology, 1, 1–27.

Bozsahin, C. (1999). Categorial morphosyntax: Transparency of the morphology-syntax-semantics interface.

Broad, R. (2015). Accent placement in Japanese blends. Master’s thesis, University of California, Los Angeles.

Broad, R., Prickett, B., Moreton, E., Pertsova, K., & Smith, J. L. (2016). Emergent faithfulness to proper nouns in novel English blends. In K. Kim (Ed.), Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Meeting of the West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL 33) (Vol. 33, pp. 77–87).

Chae, H.-R. (1990). Function argument structure, category raising, and bracketing paradoxes. In Y. No & M. Libucha (Eds.), Proceedings of the Seventh Eastern States Conference on Linguistics (ESCOL) (Vol. 90, pp. 28–39). ERIC.

Chae, H.-R. (1993). A categorial analysis of bracketing paradoxes in English. Language Research, 29(2), 163–187.

Chelliah, S. L. (1995). An autolexical account of voicing assimilation in Manipuri. In E. Schiller, E. Steinberg, & B. Need (Eds.), Trends in linguistics: Studies and monographs: Vol. 85. Autolexical theory: Ideas and Methods (pp. 11–30). Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter.

Cohn, A. C. (1989). Stress in Indonesian and bracketing paradoxes. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 7(2), 167–216.

Crysmann, B. (1999). Morphosyntactic paradoxa in Fox. In G. Bouma, E. W. Hinrichs, G.-J. M. Kruijff, & R. T. Oehrle (Eds.), Studies in constraint-based lexicalism: Vol. 3. Constraints and resources in natural language syntax and semantics (pp. 41–61). Stanford: CSLI.

Czaykowska-Higgins, E. (1993). Cyclicity and stress in Moses-Columbia Salish (Nxa’amxcin). Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 11(2), 197–278.

Czaykowska-Higgins, E. (1997). The morphological and phonological constituent structure of words in Moses-Columbia Salish (Nxa’amxcín). Trends in Linguistics Studies and Monographs, 107, 153–196.

d’Alessandro, R., & Scheer, T. (2015). Modular PIC. Linguistic Inquiry, 46(4), 593–624.

Deal, A. R. (2016). Plural exponence in the Nez Perce : A DM analysis. Morphology, 26(3–4), 313–339.

DeLisi, J. (2018). Armenian prosody in typology and diachrony. Language Dynamics and Change, 8(1), 108–133.

DeLisi, J. L. (2015). Epenthesis and prosodic structure in Armenian: A diachronic account. Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, CA.

Di Sciullo, A.-M., & Williams, E. (1987). On the definition of word. Linguistic inquiry monographs: Vol. 14. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dolatian, H. (2019a). Armenian prosody: A case for prosodic stems. In Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Chicago Linguistics Society, Chicago: Chicago Linguistics Socieity.

Dolatian, H. (2019b). Cyclicity and prosody in Armenian stress-assignment. In University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics, 25.

Dolatian, H. (2020a). Computational locality of cyclic phonology in Armenian. Ph.D. thesis, Stony Brook University.

Dolatian, H. (2020b, forthcoming). Cyclicity and prosodic misalignment in Armenian stems: Interaction of morphological and prosodic cophonologies. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-020-09487-7.

Don, J. (2004). Categories in the lexicon. Linguistics, 42, 931–956.

Don, J. (2005). On conversion, relisting and zero-derivation. SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics, 2(2), 2–16.

Donabédian, A. (2004). Arménien. In P. J. Arnaud (Ed.), Le nom composé: Données sur seize langues (pp. 3–20), Lyon: Presses Universitaires de Lyon.

Downing, L. J. (1998a). On the prosodic misalignment of onsetless syllables. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 16(1), 1–52.

Downing, L. J. (1998b). Prosodic misalignment and reduplication. In G. Booij & J. van Marle (Eds.), Yearbook of morphology 1997 (pp. 83–120). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Downing, L. J. (1999a). Prosodic stem ≠ prosodic word in Bantu. In T. A. Hall & U. Kleinhenz (Eds.), Studies on the phonological word (Vol. 174, pp. 73–98). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins Publishing.

Downing, L. J. (1999b). Verbal reduplication in three Bantu languages. In R. Kager, H. van der Hulst, & W. Zonneveld (Eds.), The prosody-morphology interface (pp. 62–89). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Downing, L. J. (2005). Morphological complexity and prosodic minimality. Catalan Journal of Linguistics, 4, 83–106.

Downing, L. J. (2006). Canonical forms in prosodic morphology. Oxford studies in theoretical linguistics: Vol. 12. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Downing, L. J. (2016). The prosodic hierarchy in Chichewa: How many levels? Studies in Prosodic Grammar, 1, 5–33.

Downing, L. J., & Kadenge, M. (2020, in press). Re-placing PStem in the prosodic hierarchy. The Linguistic Review. https://doi.org/10.1515/tlr-2020-2050.

Dum-Tragut, J. (2009). Armenian: Modern Eastern Armenian. London Oriental and African Language Library: Vol. 14. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins Publishing Company.

Elfner, E. (2015). Recursion in prosodic phrasing: Evidence from Connemara Irish. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 33(4), 1169–1208.

Ēloyan, S. A. (1972). Hodakapov ew anhodakap bardowt’yownnerë žamanakakic’ hayerenowm [The compound words with and without copulative particles in modern Armenian]. Lraber Hasarakakan Gitowt’yownneri, 7, 77–85.

Embick, D. (2010). Localism versus globalism in morphology and phonology. Linguistic Inquiry Monographs: Vol. 60. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Embick, D. (2014). Phase cycles, φ-cycles, and phonological (in) activity. In S. Bendjaballah, N. Faust, M. Lahrouchi, & N. Lampitelli (Eds.), The form of structure, the structure of forms: Essays in honor of Jean Lowenstamm (pp. 271–286). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins Publishing Company.

Embick, D. (2015). The morpheme: A theoretical introduction (Vol. 31). Boston and Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Embick, D., & Noyer, R. (2001). Movement operations after syntax. Linguistic Inquiry, 32(4), 555–595.

Ezekyan, L. K. (2007). Hayoc’ lezow [Armenian language]. Yerevan: Yerevani Petakan Hamalsarani Hratarakčowt’yown.

Falk, Y. N. (1991). Bracketing paradoxes without brackets. Lingua, 84(1), 25–42.

Fitzpatrick-Cole, J. (1994). The prosodic domain hierarchy in reduplication. Ph.D. thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, CA.

Frota, S., & Vigário, M. (2013). Review of prosody matters: Essays in honor of Elisabeth Selkirk by Borowsky et al. (2012). Phonology, 30(1), 165–172. 2012.

Fukushima, K. (1999). Bound morphemes, coordination and bracketing paradox. Journal of Linguistics, 35(2), 297–320.

Fukushima, K. (2014). Morpho-semantic bracketing paradox and compositionality: The implications of the sized inalienable possession construction in Japanese. Journal of Linguistics, 50(1), 91–141.

Fukushima, K. (2015). Compositionality, lexical integrity, and agglutinative morphology. Language Sciences, 51, 67–85.

Ġaragyowlyan, T. A. (1974). Žamanakakic’ hayereni owġġaxosowt’yownë [Moderrn Armenian orthoepy]. Yerevan: Haykakan SSH Gitowt’yownneri Akademiayi Hratarakčowt’yown.

Gordon, M. (2002). A factorial typology of quantity-insensitive stress. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 20(3), 491–552.

Gouskova, M. (2010). The phonology of boundaries and secondary stress in Russian compounds. The Linguistic Review, 27(4), 387–448.

Gouskova, M., & Roon, K. (2008). Interface constraints and frequency in Russian compound stress. In Proceedings of FASL (Vol. 17, pp. 49–63).

Grijzenhout, J., & Kabak, B. (Eds.) (2009). Phonological domains: Universals and deviations. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Number 16 in Interface explorations.

Gross, T. (2011a). Bracketing paradoxes in dependency morphology. In Language and Culture (Vol. 24, pp. 1–28).

Gross, T. (2011b). Transformational grammarians and other paradoxes. In 5th International conference on meaning-text theory (pp. 88–97).

Guzzo, N. B. (2018). The prosodic representation of composite structures in Brazilian Portuguese. Journal of Linguistics, 54(4), 683–720.

Halle, M., & Kenstowicz, M. (1991). The free element condition and cyclic versus noncyclic stress. Linguistic Inquiry, 22(3), 457–501.

Halle, M., & Nevins, A. (2009). Rule application in phonology. In E. Raimy & C. E. Cairns (Eds.), Contemporary views on architecture and representations in phonology. Current studies in linguistics: Vol. 48 (pp. 355–383). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Halle, M., & Vergnaud, J.-R. (1987a). An essay on stress. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Halle, M., & Vergnaud, J.-R. (1987b). Stress and the cycle. Linguistic Inquiry, 18(1), 45–84.

Han, E. (1995). Prosodic structure in compounds. Ph.D. thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, CA.

Harðarson, G. R. (2016). Peeling away the layers of the onion: On layers, inflection and domains in icelandic compounds. The Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics, 19(1), 1–47.

Harðarson, G. R. (2017). Cycling through grammar: On compounds, noun phrases and domains. Ph.D. thesis, University of Connecticut.

Harðarson, G. R. (2018). Forming a compound and spelling it out. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics, 24, 11.

Hargus, S. (1993). Modeling the phonology–morphology interface. See Hargus and Kaisse (1993), pp. 45–74.

Hargus, S., & Kaisse, E. M. (Eds.) (1993). Studies in lexical phonology. Phonetics and phonology: Vol. 4. San Diego: Academic Press.

Harley, H. (2009). Compounding in distributed morphology. In R. Lieber & P. Štekauer (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of compounding (pp. 129–143). Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

Haugen, J. D., & Harley, H. (2013). Head-marking inflection and the architecture of grammatical theory. In S. T. Bischoff, D. Cole, A. V. Fountain, & M. Miyashita (Eds.), The persistence of language: Constructing and confronting the past and present in the voices of Jane H. Hill (Vol. 8, p. 133). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins Publishing.

Hoeksema, J. (1985). Categorial morphology. Groningen: van Denderen.

Hoeksema, J. (1987). Relating word structure and logical form. Linguistic Inquiry, 18(1), 119–126.

Hoeksema, J. (1988). Head-types in morpho-syntax. Yearbook of Morphology, 1, 123–137.

Hoeksema, J. (1992). The head parameter in morphology and syntax. Language and Cognition, 2, 119–132.

Hoeksema, J., & Janda, R. D. (1988). Implications of process-morphology for categorial grammar. In R. T. Oehrle, E. Bach, & D. Wheeler (Eds.), Categorial grammars and natural language structures (pp. 199–247). Berlin: Springer.

Hyman, L. M. (2008). Directional asymmetries in the morphology and phonology of words, with special reference to Bantu. Linguistics, 46(2), 309–350.

Inkelas, S. (1989). Prosodic constituency in the lexicon. Ph.D. thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, California.

Inkelas, S. (1993). Deriving cyclicity. See Hargus and Kaisse (1993), pp. 75–100.

Inkelas, S., & Zoll, C. (2005). Reduplication: Doubling in Morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ito, J., & Mester, A. (2009) The extended prosodic word. See Grijzenhout and Kabak (2009), pp. 135–194.

Ito, J., & Mester, A. (2012). Recursive prosodic phrasing in Japanese. In T. Borowsky, S. Kawahara, S. Takahito, & M. Sugahara (Eds.), Prosody matters: Essays in honor of Elisabeth Selkirk (pp. 280–303). London: Equinox Publishing.

Ito, J., & Mester, A. (2013). Prosodic subcategories in Japanese. Lingua, 124, 20–40.

Kabak, B., & Revithiadou, A. (2009). An interface approach to prosodic word recursion. See Grijzenhout and Kabak (2009), pp. 105–133.

Kang, B-m. (1993). Unhappier is really a “bracketing paradox”. Linguistic Inquiry, 24(4), 788–794.

Karapetyan, S. H. (2016). Goyakanakan himk’erov baġadrowt’yownnerë hayereni ew anglereni baṙakazmakan hamakargowm [Noun-based structural patterns in the Armenian and English word-formation systems]. Ph.D. thesis, HH GAA Hračya Ač̣aṙyani anvan lezvi institowt.

Khanjian, H. (2009). Stress dependent vowel reduction. In I. Kwon, H. Pritchett, & J. Spence (Eds.), Proceedings of the 35th annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (pp. 178–189). Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Linguistics Society.

Kilborne-Ceron, O., Newell, H., Noonan, M., & Travis, L. (2016). Phase domains at pf: Root suppletion and its implications. See Siddiqi and Harley (2016), pp. 121–161.

Kim, J. J.-R. (1991). Bracketing paradoxes in natural language processing. Language Research, 27(1), 99–117.

Kim, J. J.-R. (1992). Bracketing paradoxes in Korean. Korean Linguistics, 7, 53–71.

Kiparsky, P. (1983). Word-formation and the lexicon. In F. Ingemann (Ed.), Proceedings of the 1982 Mid-America Linguistics Conference, Lawrence (pp. 3–29). Mid-America Linguistics Conference: University of Kansas.

Kiparsky, P. (1993). Blocking in non-derived environments. See Hargus and Kaisse (1993), 277–313.

Kitagawa, Y. (1986). More on bracketing paradoxes. Linguistic Inquiry, 17(1), 177–183.

Ladd, D. R. (1986). Intonational phrasing: The case for recursive prosodic structure. Phonology, 3, 311–340.

Lieber, R. (1989). On percolation. Yearbook of Morphology, 2, 95–138.

Lieber, R. (2004). Morphology and lexical semantics (Vol. 104). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Light, M. (1991). Taking the paradoxes out of bracketing in morphology. In Proceedings of the second formal Linguistics Society of Mid-America conference. University of Michigan.

Lochbihler, B. (2017). Syntactic domain types and PF effects. See Newell et al. (2017), pp. 74–99.

Macak, M. J. (2016). Studies in classical and modern Armenian phonology. Ph.D. thesis, University of Georgia.

Marantz, A. (1988). Clitics, morphological merger, and the mapping to phonological structure. In Theoretical morphology (pp. 253–270). San Diego: Academic Press.

Margaryan, A. S. (1997). Z̈amanakakic’ hayoc’ lezow: Hnčyownabanowt’yown [Contemporary Armenian language: Phonology]. Yerevan: Yerevani Petakan Hamalsarani Hratarakčowt’yown.

Marowt’yan, A. A. (2003). Miavank baġadričov bard goyakanneri hognakii kazmowt’yownë žamanakakic’ hayerenowm [Plural formation of monosyllabic-final compounds in contemporary Armenian]. Lraber Hasarakakan Gitowt’yownneri, 2, 52–62.

Marvin, T. (2002). Topics in the stress and syntax of words. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Mascaró, J. (1976). Catalan phonology and the phonological cycle. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Matushansky, O., & Marantz, A. (Eds.) (2013). Distributed morphology today. Cambridge: MIT Press.

McPherson, L., & Hayes, B. (2016). Relating application frequency to morphological structure: The case of Tommo So vowel harmony. Phonology, 33(1), 125–167.

Miller, T. L. (2018). The phonology-syntax interface and polysynthesis: A study of Kiowa and Saulteaux Ojibwe. Ph.D. thesis, University of Delaware.

Miller, T. L. (2020). Navigating the phonology-syntax interface and Tri-P mapping. In Proceedings of the annual meetings on phonology (Vol. 8).

Mkrtčyan, R. (1972). Bard baṙeri dasakargowmë hayerenowm [The classification of Armenian compounds. Lraber Hasarakakan Gitowt’yownneri, 3, 100–106.

Mkrtčyan, R. (1973). Orošič-orošyali haraberowt’yamb baġadričnerov bardowt’yownnern ardi hayerenowm [Compound words of the type definer-defined in the modern Armenian language]. Lraber Hasarakakan Gitowt’yownneri, 4, 45–50.

Mkrtčyan, R. (1977). Bard baṙeri dasakargowmë ew nranc’ baġadričneri imastayin p’oxharaberowt’yownë žamanakakic’ hayerenowm [The classification of complex words and the meaning of their components in contemporary Armenian]. Lezvi ew oč̣i harc’er, 4, 77–158.

Mkrtčyan, R. (1980). Bard baṙeri baġadričneri hamadreliowt’yan sahmanap’akič hangamank’nerë [Factors limiting the compatibility of components in compound words]. Lraber Hasarakakan Gitowt’yownneri, 1, 34–40.

Moreton, E., Smith, J. L., Pertsova, K., Broad, R., & Prickett, B. (2017). Emergent positional privilege in novel english blends. Language, 93(2), 347–380.

Moskal, B., & Smith, P. W. (2019). The status of heads in morphology. In Oxford research encyclopedia of linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Müller, S. (2003). Solving the bracketing paradox: An analysis of the morphology of German particle verbs. Journal of Linguistics, 39(2), 275–325.

Nespor, M. (1999). Stress domains. In H. van der Hulst (Ed.), Word prosodic systems in the languages of Europe (pp. 117–159). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Nespor, M., & Ralli, A. (1996). Morphology-phonology interface: Phonological domains in Greek compounds. The Linguistic Review, 13(3–4), 357–382.

Nespor, M., & Vogel, I. (1986). Prosodic phonology. Dordrecht: Foris.

Newell, H. (2005). Bracketing paradoxes and particle verbs: A late adjunction analysis. In Proceedings of ConSOLE XIII, (pp. 249–272). Leiden: University of Leiden.

Newell, H. (2008). Aspects of the morphology and phonology of phases. Ph.D. thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC.

Newell, H. (2017). Nested phase interpretation and the PIC. See Newell et al. (2017), pp. 20–40.

Newell, H. (2019). Bracketing paradoxes in morphology. In Oxford research encyclopedia of linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Newell, H., Noonan, M., & Piggott, G. (Eds.) (2017). The structure of words at the interfaces (Vol. 68). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Newell, H., & Piggott, G. (2014). Interactions at the syntax-phonology interface: Evidence from ojibwe. Lingua, 150, 332–362.

Nikolou, K. (2009). The role of recursivity in the phonological word. In A. Karasimous, C. Vlachos, E. Dimela, M. Giakoumelou, M. Pavlakou, N. Koutsoukos, & D. Bougonikolou (Eds.), Proceedings of the First Patras International Conference of Graduate students in Linguistics (PICGL1) (pp. 41–52). University of Patras.

Odden, D., & Odden, M. (1985). Ordered reduplication in Kihehe. Linguistic Inquiry, 16(3), 497–503.

Olsen, B. A. (2011). The noun in Biblical Armenian: Origin and word-formation-with special emphasis on the Indo-European heritage (Vol. 119). Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter.

Oltra-Massuet, M. I. (1999). On the notion of theme vowel: A new approach to Catalan verbal morphology. Master’s thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Özçelik, Ö. (2017). The foot is not an obligatory constituent of the prosodic hierarchy: “stress” in Turkish, French and child English. The Linguistic Review, 34(1), 157–213.

Peperkamp, S. A. (1997). Prosodic words. The Hague: Holland Academic Press.

Pesetsky, D. (1979). Russian morphology and lexical theory. Unpublished manuscript.

Pesetsky, D. (1985). Morphology and logical form. Linguistic Inquiry, 16(2), 193–246.

Raffelsiefen, R. (2005). Paradigm uniformity effects versus boundary effects. In L. J. Downing, T. A. Hall, & R. Raffelsiefen (Eds.), Paradigms in phonological theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rainer, F. (1993). Head-operations in Spanish morphology. In G. Booij & J. van Marle (Eds.), Yearbook of morphology 1992 (pp. 113–128). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Ralli, A. (2008). Compound markers and parametric variation. STUF-Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung, 61(1), 19–38.

Ralli, A. (2012). Compounding in modern Greek (Vol. 2). Berlin: Springer.

Revithiadou, A. (1999). Headmost accent wins: Head dominance and ideal prosodic form in lexical accent systems. Ph.D. thesis, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ.

Roon, K. (2005). Stress in Russian compound nouns: Head dominance or root control. In Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics (FASL-14) (pp. 319–330). The Princeton Meeting.

Sadock, J. M. (1985). Autolexical syntax: A proposal for the treatment of noun incorporation and similar phenomena. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 3(4), 379–439.

Samuels, B. D. (2011). Phonological architecture: A biolinguistic perspective. Oxford studies in biolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Samuels, B. (2012). Consequences of phases for morpho-phonology. In A. J. Gallego (Ed.), Phases: Developing the framework (pp. 251–282). Berlin/Boston: Mouton De Gruyter.

Sande, H., Jenks, P., & Inkelas, S. (2020). Cophonologies by ph(r)ase. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 1–51.

Sargsyan, A. (1979). Verǰin miavank baġadričov bard baṙeri hognaki t’vi zowgajewerë žamanakakic’ hayerenowm [Doublets in the plural of monosyllabic-final compounds in contemporary Armenian]. Lraber Hasarakakan Gitowt’yownneri, 4, 35–44.

Sargsyan, A. (1984). Goyakani holovman tiperi vičakagrakan bnowt’agirë ardi hayerenowm [statistical characterization of nominal declension types in modern Armenian]. Lraber Hasarakakan Gitowt’yownneri, 5, 23–30.

Sargsyan, A. (1987). Goyakanakan zowgajewowt’yownnerë žamanakakic’ hayerenowm [Noun doublets in contemporary Armenian]. Lezvi ew oč̣i harc’er, 10, 123–230.

Scalise, S., & Fábregas, A. (2010). The head in compounding. In S. Scales & I. Vogel (Eds.), Cross-disciplinary issues in compounding (pp. 109–125). Amsterdam and Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Scalise, S., Fábregas, A., & Forza, F. (2009). Exocentricity in compounding. Gengo kenky. Journal of the Linguistic Society of Japan, 135, 49–84.

Scheer, T. (2011). A guide to morphosyntax-phonology interface theories: How extra-phonological information is treated in phonology since Trubetzkoy’s Grenzsignale. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Scheer, T. (2012). Chunk definition in phonology: Prosodic constituency vs. phase structure. In M. Bloch-Trojnar & A. Bloch-Rozmej (Eds.), Modules and interfaces (pp. 221–253). Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL.

Selkirk, E. (1996). The prosodic structure of function words. In J. L. Morgan & K. Demuth (Eds.), Signal to syntax: Bootstrapping from speech to grammar in early acquisition (Vol. 187, p. 214). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Selkirk, E. (2011). The syntax-phonology interface. In J. Goldsmith, J. Riggle, & A. C. L. Yu (Eds.), The handbook of phonological theory (2nd ed., pp. 435–483). Oxford: Blackwell.

Selkirk, E. O. (1982). The syntax of words. Linguistic inquiry monographs: Vol. 7. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sevak, G. (2009). Jhamanakakic hayoc lezvi dasy’nt’ac [Course in Modern Armenian]. Yerevan: YSU Publishing House.

Shaw, P. A. (2005). Non-adjacency in reduplication. In B. Hurch (Ed.), Studies on reduplication. Empirical approaches to language typology (Vol. 28, pp. 161–210). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Shaw, K. E. (2013). Head faithfulness in lexical blends: A positional approach to blend formation. Master’s thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Shaw, K. E., White, A. M., Moreton, E., & Monrose, F. (2014). Emergent faithfulness to morphological and semantic heads in lexical blends. In J. Kingston, C. Moore-Cantwell, J. Pater, & R. Staubs (Eds.), Proceedings of the annual meetings on phonology (Vol. 1).

Shwayder, K. (2015). Words and subwords: Phonology in a piece-based syntactic morphology. Ph.D. thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Siddiqi, D., & Harley, H. (Eds.) (2016). Morphological metatheory. Linguistik aktuell/Linguistics today: Vol. 229.

Sowk’iasyan, A. M. (2004). Z̈amanakakic’ hayoc’ lezow (Hnčyownabanowt’yown, baṙagitowt’yown, baṙakazmowt’yown) [Modern Armenian phonology, lexicology, and word-formation]. Yerevan: Yerevani Petakan Hamalsarani Hratarakčowt’yown.

Spencer, A. (1988). Bracketing paradoxes and the English lexicon. Language, 64(4), 663–682.

Sproat, R. W. (1985). On deriving the lexicon. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Sproat, R. (1988). Bracketing paradoxes, cliticization and other topics: The mapping between syntactic and phonological structure. In M. Everaert, A. Evers, R. HuyBregts, & M. Trommelen (Eds.), Morphology and modularity (pp. 339–360). Dordrecht: Foris.

Sproat, R. (1992). Unhappier is not a “bracketing paradox”. Linguistic Inquiry, 23(2), 347–352.

Steddy, S. (2019). Compounds, composability, and morphological idiosyncrasy. The Linguistic Review, 36(3), 453–483.

Strauss, S. L. (1982). On “relatedness paradoxes” and related paradoxes. Linguistic Inquiry, 13(4), 694–700.

Stump, G. T. (1995a). Two types of mismatch between morphology and semantics. In E. Schiller, E. Steinberg, & B. Need (Eds.), Trends in linguistics: Studies and monographs: Vol. 85. Autolexical theory: Ideas and methods (pp. 291–318). Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter.

Stump, G. T. (1995b). The uniformity of head marking in inflectional morphology. In Yearbook of morphology 1994 (pp. 245–296). Berlin: Springer.

Stump, G. T. (2001). Inflectional morphology: A theory of paradigm structure. Cambridge Studies in Linguistics: Vol. 93. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Szpyra, J. (1989). The phonology-morphology interface: Cycles, levels and words. London: Routledge.

Tat, D. (2013). Word syntax of nominal compounds: Internal and aphasiological evidence from Turkish. Ph.D. thesis, The University of Arizona.

Toparlak, T. (2019). Etudes phonétiques en arménien. Master’s thesis, Université Paris. 3 - Sorbonne Nouvelle.

T’oxmaxyan, R. M. (1971). Z̈amanakakic’ hayereni baṙayin šeštë [Modern Armenian word stress]. Lraber Hasarakakan Gitowt’yownneri, 2, 60–64.

T’oxmaxyan, R. M. (1975). Žamanakakic’ hayereni baṙayin šešti bnowyt’ë [The essence of the word stress of contemporary Armenian]. Lezvi ew oč̣i harc’er, 3, 123–207.

T’oxmaxyan, R. M. (1983). Z̈amanakakic’ hayereni šeštabanowt’yownë [The accentology of contemporary Armenian]. Yerevan: Haykakan SSH Gitowt’yownneri Akademiayi Hratarakčowt’yown.

Truckenbrodt, H. (1999). On the relation between syntactic phrases and phonological phrases. Linguistic Inquiry, 30(2), 219–255.

Tyler, M. (2019). Simplifying match word: Evidence from English functional categories. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics, 4(1).

Vaux, B. (1998). The phonology of Armenian. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Vaux, B. (2003). Syllabification in Armenian, Universal Grammar, and the lexicon. Linguistic Inquiry, 34(1), 91–125.

Vigário, M. (2010). Prosodic structure between the prosodic word and the phonological phrase: Recursive nodes or an independent domain? The Linguistic Review, 27(4), 485–530.

Vogel, I. (2009). The status of the clitic group. See Grijzenhout and Kabak (2009), pp. 15–46)

Vogel, I. (2010). The phonology of compounds. In S. Scales & I. Vogel (Eds.), Cross-disciplinary issues in compounding (pp. 145–167). Amsterdam and Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Vogel, I. (2012). Recursion in phonology? In B. Botma & R. Noske (Eds.), Phonological explorations: Empirical, theoretical and diachronic issues (pp. 41–62). Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter.

Vogel, I. (2016). Life after the strict layer hypothesis: Prosodic structure geometry. In Y. Zhang & H. Qian (Eds.), Prosodic studies: Challenges and prospects. London: Routledge.

Wagner, M. (2005). Prosody and recursion. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Wagner, M. (2010). Prosody and recursion in coordinate structures and beyond. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 28(1), 183–237.

Williams, E. (1981). On the notions “lexically related” and “head of a word”. Linguistic Inquiry, 12(2), 245–274.

Wolf, M. (2013). Candidate chains, unfaithful spell-out, and outwards-looking phonologically-conditioned allomorphy. Morphology, 23(2), 145–178.

Xačatryan, A. (1988). Z̈amanakakic’ hayereni hnčyownabanowt’yown [Phonology of Contemporary Armenian]. Yerevan: Haykakan SSH Gitowt’yownneri Akademiayi Hratarakčowt’yown.

Xačatryan, A. (2009a). Bayakan baġadričov kazmvaç bown kam iskakan bardowt’yownneri šarahyowsakan haraberowt’yownnerë [Syntactic relations of compounds made from verbs]. Kant’eġ. Gitakan hodvaçneri žoġovaçow, 2, 86–91.

Xačatryan, A. (2009b). Bayakan himk’erov kazmvaç bown kam iskakan bardowt’yownneri jewabanakan kaġaparnerë [Morphological models of real or essential compounds formed with verbal stems]. Lraber Hasarakakan Gitowt’yownneri, 3, 217–224.

Zec, D. (2005). Prosodic differences among function words. Phonology, 22(1), 77–112.

Zwicky, A. M. (1985). Heads. Journal of Linguistics, 21(1), 1–29.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Counter-cyclicity with alternatives to stratal phonology

Appendix: Counter-cyclicity with alternatives to stratal phonology

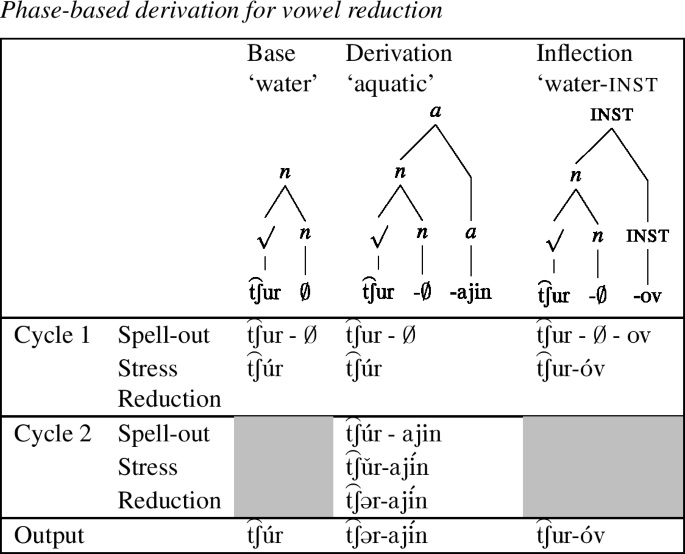

Setting aside prosodic variation, I showed that counter-cyclic approaches like Morphological Merger are partially adequate for modeling the bracketing paradox but they contradict the stratal phonology of Armenian. I instead argued that the bracketing paradox required a cyclic approach like Head-Operations which did not contradict the stratal phonology. In this appendix, I sketch out two alternative analyses that combine counter-cyclic approaches with two alternative to stratal phonology: phase-based phonology and Halle and Vergnaud (1987a)’s free interleaving of cyclic and non-cyclic phonology. I argue that these alternatives have problems in modelling the entirety of compound phonology and morphology.

1.1 A.1 Empirical problems with phase-based phonology

Phonological Derivation by Phase (PDb) is a conceptual offshoot of lexical phonology (Marvin 2002; Newell 2008; Samuels 2011, 2012). While several theoretical assumptions of PDbP are still being debated (Matushansky and Marantz 2013; Siddiqi and Harley 2016; Newell et al. 2017), the following discussion refers to the more commonly held assumptions. I argue that when combined with Morphological Merger, PDbP can model the bracketing paradox and the application of stem-level rules in endocentric compounds. But it has problems in the application of stem-level rules in exocentric compounds.

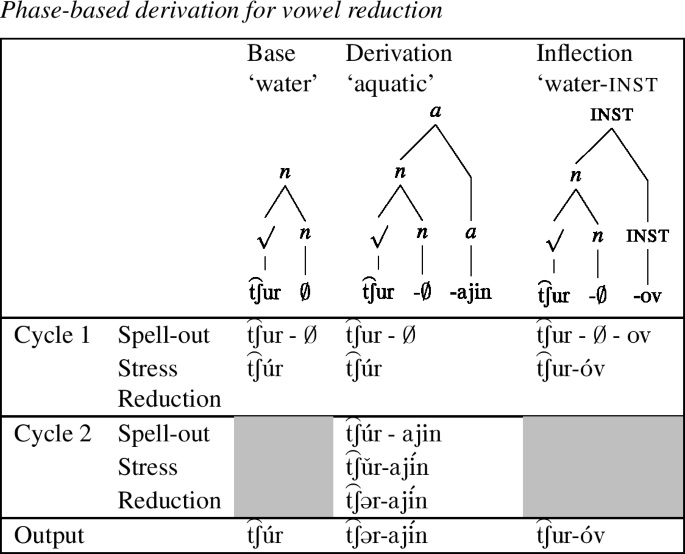

PDbP assumes that words are cyclically derived where cycles are defined in terms of phase head n, v, a (= derivational suffixes). Non-phase heads (= inflectional suffixes) cannot trigger spell-out and thus do not trigger any cycles. They are not just post-cyclic, but they are part of the same cycle as derivation (Embick 2010). PDbP generally assumes that there is only one cophonology (= no stem vs. word strata) and that there are no prosodic constituents (Scheer 2011, 2012). Cyclic derivations generally respect the phonological structure created on previous cycles, whether by the Phase Impenetrability Condition (Marvin 2002), Phonological Persistence (Newell and Piggott 2014), phase-based faithfulness (McPherson and Hayes 2016), or the use of cophonologies (Sande et al. 2020).

Recall that destressed high vowel reduction (DHR) applies in derivation, but not inflection. It applies in both endocentric and exocentric compounds.

-

(54)

First, without strata, PDbP cannot directly capture the fact that inflection can trigger some but not all stem-level processes. The null hypothesis is that inflection cannot trigger its own cycle because inflection is a non-phase head. Instead, inflection is incorporated into the same phase-cycle as the previous (covert or overt) derivational suffix (Embick 2010). For simplex stems, this would allow inflection to trigger stress shift but not DHR.

-

(55)

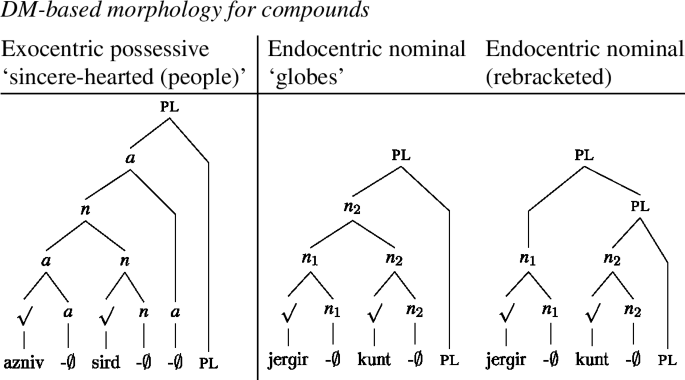

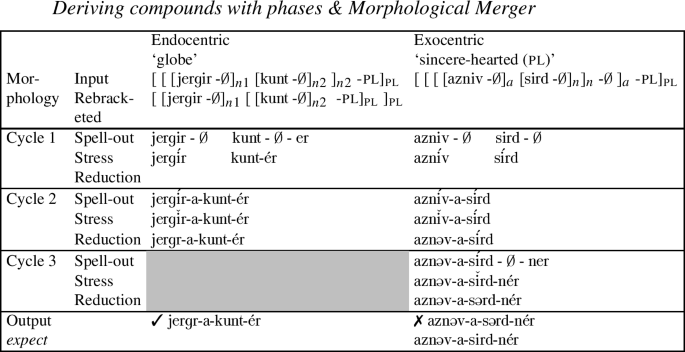

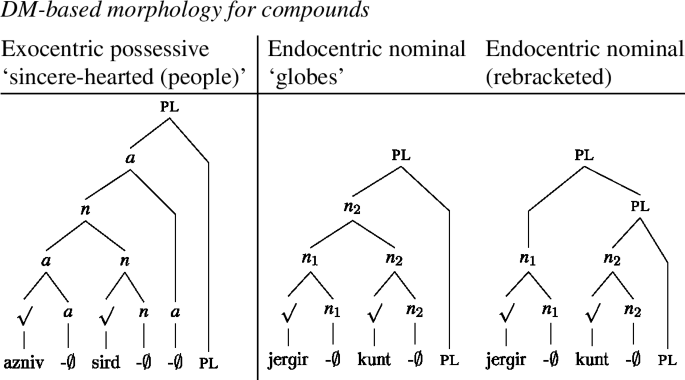

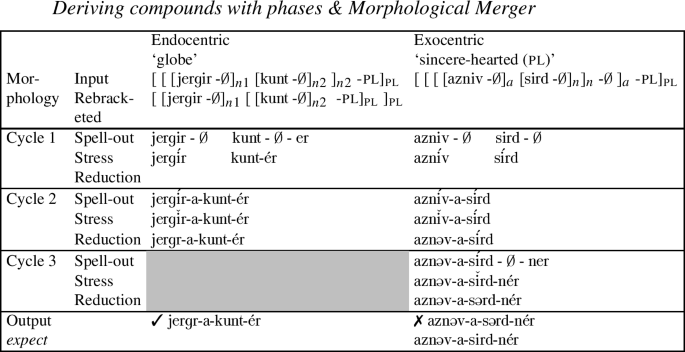

When combined with Morphological Merger, PDbP can model the bracketing paradox. Reduction correctly applies in endocentric compounds; howeveer, reduction incorrectly applies in exocentric compounds. I assume the following morphological structure for endocentric and exocentric compounds. These structures are adapted from conventions in Distributed Morphology (Harley 2009; Harðarson 2016, 2017, 2018). Each stem is made up of a root and covert category affix. In the endocentric compound, Stem1 is adjoined to Stem2, as indicated by the different indexes for n. In exocentric compounds, Stem1 is also adjoined to Stem2. The entire compound takes a covert adjectivizer a (Steddy 2019). As before, I assume that linking vowels are generated in phonological spell-out in the PF component as dissociated morphemes (Embick 2015).

-

(56)

I go through a derivation below. Following morphological rebracketing, the pl forms a constituent with Stem2 in endocentric compounds. The pl is spelled-out as -er in the first cycle with Stem2. The two stems are concatenated in Cycle 2 and reduction correction applies.

-

(57)

But, reduction is incorrectly predicted to apply to Stem2 in exocentric compounds. In the first two cycles, each stem is spelled-out and then concatenated. By the second cycle, the compound has undergone stress shift to Stem2 and reduction on Stem1:  . At this stage, the singular compound is an endocentric noun, but it must be reinterpreted as an exocentric possessive by taking a covert adjectivizer a (Steddy 2019). But this causes a problem for the phonology. In Cycle 3, the a category-node for the compound is spelled-out alongside the pl. Although the correct plural is generated, the monostratal phase-based phonology must apply stress shift to pl and reduction on Stem2: *

. At this stage, the singular compound is an endocentric noun, but it must be reinterpreted as an exocentric possessive by taking a covert adjectivizer a (Steddy 2019). But this causes a problem for the phonology. In Cycle 3, the a category-node for the compound is spelled-out alongside the pl. Although the correct plural is generated, the monostratal phase-based phonology must apply stress shift to pl and reduction on Stem2: * .

.

An additional conceptual problem is that the above PDbP system contradicts Phonological Persistence. Phonological Persistence (Newell and Piggott 2014) predicts that structure-changing processes (reduction) should be possible within the same phase. By being in the same phase-cycle as the root, inflection would not be blocked from changing any structure: reduction would be incorrectly predicted to be preferred. In contrast, derivation would be incorrectly predicted to only trigger structure-building processes (no reduction) because it is in a separate phase.

In order to get the right reduction patterns, the simplest solution is to allow inflection to trigger its own cycles (Bobaljik and Wurmbrand 2013).Footnote 27 Phonological Persistence would then block inflection from triggering DHR. However, this implies an informal stratification of phonological processes. Furthermore, we still need a separate mechanism that allows derivation to trigger structure-changing processes like reduction.

To handle Armenian, PDbP can be tweaked to include strata via final vs. non-final phases (Lochbihler 2017), separation of phonological and morphosyntactic cycles (Embick 2014; d’Alessandro and Scheer 2015), and allowing inflection to trigger its own cycles (Bobaljik and Wurmbrand 2013; Shwayder 2015; Kilborne-Ceron et al. 2016). Doing so reduces the differences between PDbP vs. Stratal/Lexical Phonology (cf. Bonet et al. 2019). This brings us back into the original problem of how Morphological Merger contradicts stratal phonology.

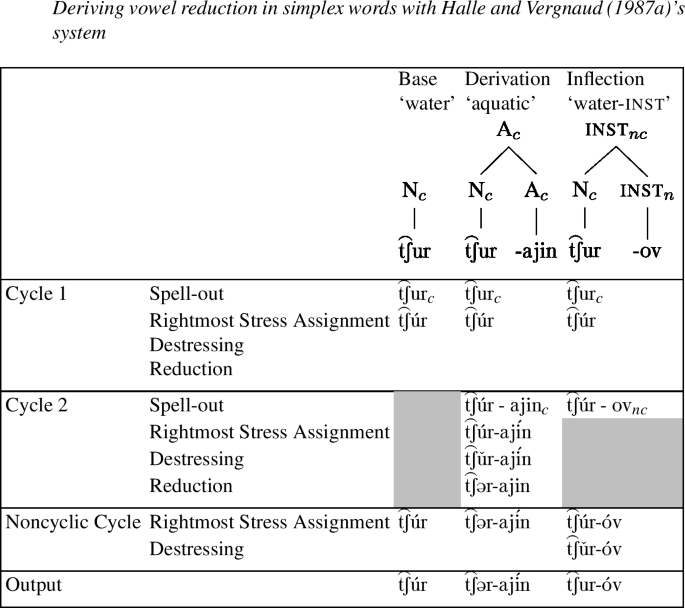

1.2 A.2 Conceptual problems in the free interleaving of cyclic and non-cyclic phonology

Phase-based phonology assumes that it is morphosyntactically predictable if a given morpheme will trigger a cycle or not. In contrast, the model of phonological cyclicity in Halle and Vergnaud (1987a,b) removes this predictability. Here, where an affix can trigger cyclic rules or not is diacritically determined. There are also no constraints on the ordering of cyclic and non-cyclic affixes. Scheer (2011, 9) calls this system “selective spell-out”. Furthermore, PDbP assumes a single cophonology or set of rules. In contrast, Halle and Vergnaud (1987a,b) assume two cophonologies: cyclic vs. noncyclic rules. Whether a phonological process is cyclic or not is diacritically determined. I show that this lack of constraints makes it possible for Halle and Vergnaud (1987a) to model the Armenian data. However, this model does not find independent evidence elsewhere in Armenian.Footnote 28

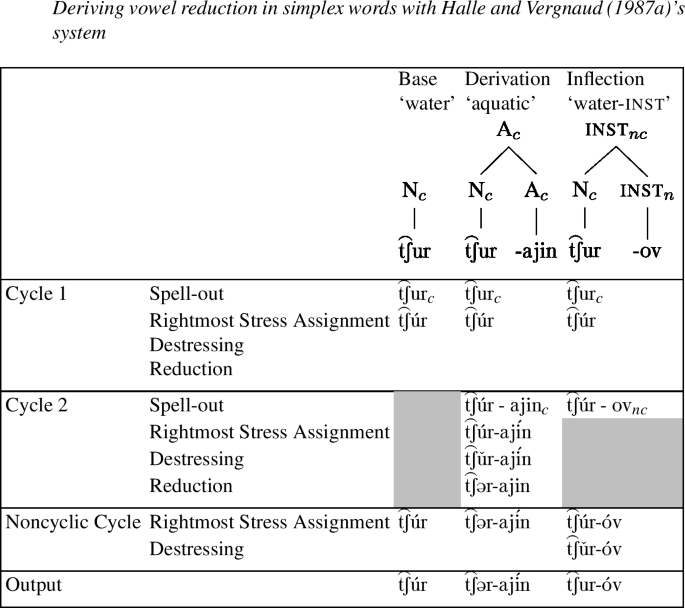

Consider again the application of destressed high vowel reduction in non-compounds. To make the comparison easier, I decompose stress shift into two processes: rightmost stress assignment and destressing. Informally, Rightmost Stress Assignment places stress on the rightmost full vowel; Destressing removes stress from a stressed vowel which is not the rightmost stressed vowel.

In my analysis, reduction is a stem-level rule which applies in derivation (the MStem) but not inflection (the MWord). Stress-assignment and destressing are both stem-level and word-level rules. In Halle and Vergnaud (1987a,b)’s system, stem-level rules are called cyclic rules while word-level rules are noncyclic. All derivational and inflectional suffixes are diacritically marked as triggering cyclic (c) and noncyclic (nc) rules respectively. The concept of MStems vs. MWords is not relevant.

-

(58)

To match the representations used in Halle and Vergnaud (1987a), I do not assume covert category suffixes on roots. In Cycle 1, the noun is spelled-out. Because the noun has a cyclic diacritic, it triggers the cyclic rules of stress and (vacuous) reduction to form  . In Cycle 2, the derivational suffix

. In Cycle 2, the derivational suffix  is spelled out and triggers the cyclic rules of stress and reduction:

is spelled out and triggers the cyclic rules of stress and reduction:  . But, in Cycle 2, we also spell-out the noncyclic inflectional suffix -ov. Halle and Vergnaud (1987a,b) argue that non-cyclic affixes can’t trigger cyclic rules. They also can’t trigger non-cyclic rules. Thus, no rules apply at all. Finally, all the words undergo a final noncyclic cycle where only noncyclic rules apply. This gets us final stress in

. But, in Cycle 2, we also spell-out the noncyclic inflectional suffix -ov. Halle and Vergnaud (1987a,b) argue that non-cyclic affixes can’t trigger cyclic rules. They also can’t trigger non-cyclic rules. Thus, no rules apply at all. Finally, all the words undergo a final noncyclic cycle where only noncyclic rules apply. This gets us final stress in  .

.

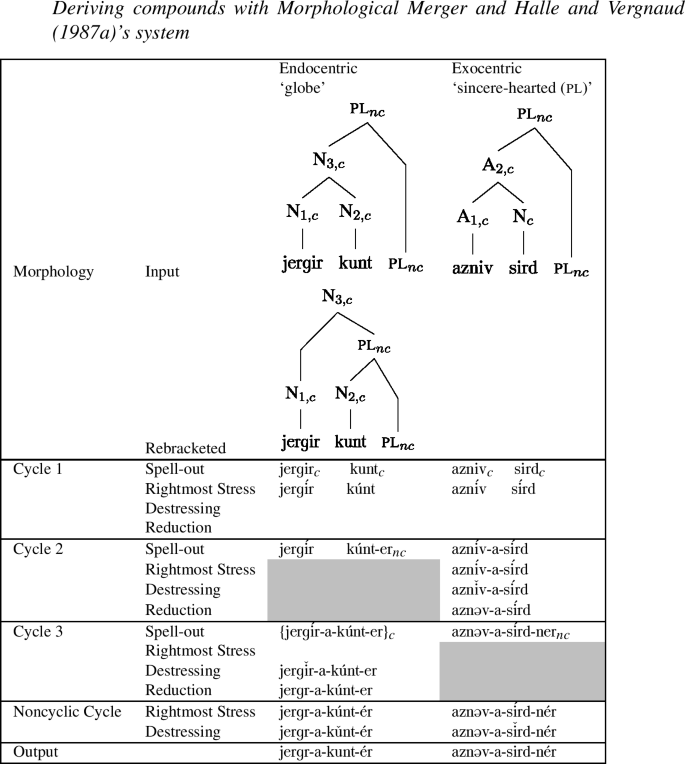

For compounding, I assume that the compound’s category is not due to adjunction (Selkirk 1982). When combined with Morphological Merger or any other rebracketing process, Halle and Vergnaud (1987a)’s model can handle the bracketing paradox. It can also arguably trigger the right cyclic rules. The problem is that they rely on the Strict Cyclicity Condition (Mascaró 1976), a debunked principle (Kiparsky 1993).

-

(59)

The exocentric plural has a straightforward derivation. In Cycle 1, the two stems undergo the cyclic rules and get stressed. In Cycle 2, they are concatenated and undergo the cyclic rules of stress and reduction. Note that Rightmost Stress Assignment does not remove primary stress from Stem1. Removal is done by Destressing. In Cycle 3, the plural suffix is added. Because the suffix is non-cyclic, it does not trigger cyclic stress shift and reduction. The word eventually undergoes the non-cyclic stratum and gets final stress.

For the endocentric plural, the first two cycles are straightforward. In Cycle 1, the stems are stressed. In Cycle 2, the second stem gets the plural suffix -er. Because the suffix is non-cyclic, then no rules apply. In Cycle 3, the stems are concatenated. The suffix does not get any stress because of the Strict Cycle Condition (SCC). SCC blocks rightmost stress assignment on the suffix -er because the substring er was created in the previous cycle. We still get destressing and reduction on Stem1’s u because concatenation made u no longer a final vowel. In the final noncyclic cycle, the compound undergoes the noncyclic rules to get final stress.

As shown, Halle and Vergnaud (1987a)’s system can work for Armenian. However, it has three conceptual problems. First, the derivation mainly worked because of the SCC. In Cycle 3, the input was  and the output was

and the output was  with reduction on Stem1. In this cycle, the SCC blocked stress shift to the suffix -er, which itself blocked destressing and reduction in *

with reduction on Stem1. In this cycle, the SCC blocked stress shift to the suffix -er, which itself blocked destressing and reduction in * . Current incarnations of Halle and Vergnaud (1987a)’s system still assume that the SCC plays some role (Halle and Nevins 2009). However, the SCC is a dubious principle and has been debunked (Kiparsky 1993). An alternative blocking systems like the Phrase Impenetrability Condition are likewise dubious (Embick 2014; Newell 2017). Footnote 29 See Scheer (2011) and Bermúdez-Otero (2008) for a historical overview on the development and failures of the SCC.

. Current incarnations of Halle and Vergnaud (1987a)’s system still assume that the SCC plays some role (Halle and Nevins 2009). However, the SCC is a dubious principle and has been debunked (Kiparsky 1993). An alternative blocking systems like the Phrase Impenetrability Condition are likewise dubious (Embick 2014; Newell 2017). Footnote 29 See Scheer (2011) and Bermúdez-Otero (2008) for a historical overview on the development and failures of the SCC.

Second, Halle and Vergnaud (1987a) assumes that it is arbitrary and unpredictable whether an affix is cyclic or not. This misses the fact that in Armenian all cyclic and non-cyclic affixes are respectively derivational and inflectional morphology. Third, Halle and Vergnaud (1987a)’s system allows cyclic and noncyclic affixes to linearly precede and follow each other, e.g., English patent-abl-ity where -able is Level 2, while -ity is Level 1 (Halle and Kenstowicz 1991; also in Salishan: Czaykowska-Higgins 1993). It is then surprising that these ordering paradoxes are not found in Armenian. All noncyclic affixes are inflectional, and they follow all other derivational morphology.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dolatian, H. The role of heads and cyclicity in bracketing paradoxes in Armenian compounds. Morphology 31, 1–43 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-020-09368-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-020-09368-0

as <

as < >, and the lax mid-vowels

>, and the lax mid-vowels  are transcribed as <

are transcribed as < >. Armenian citations are Romanized based on the ISO 9985 transliteration system.

>. Armenian citations are Romanized based on the ISO 9985 transliteration system. ‘small + light + picture’ →

‘small + light + picture’ →  ‘micro-photograph’. A linking vowel is used between each stem. These large compounds are rarely used and mostly restricted to higher registers. Data on their phonology is limited and I do not discuss them.

‘micro-photograph’. A linking vowel is used between each stem. These large compounds are rarely used and mostly restricted to higher registers. Data on their phonology is limited and I do not discuss them. .

. ‘waters’. I argue this is because of prosodic misalignment (Dolatian

‘waters’. I argue this is because of prosodic misalignment (Dolatian  ‘rain-waters’. The derivation above is just for Western Armenian. There are also fossilized rules of destressed e-to-i reduction and destressed ja-to-e reduction. These rules apply in some derivatives:

‘rain-waters’. The derivation above is just for Western Armenian. There are also fossilized rules of destressed e-to-i reduction and destressed ja-to-e reduction. These rules apply in some derivatives:  ‘love’ vs.

‘love’ vs.  ‘affectionate’,

‘affectionate’,  ‘apostle vs.

‘apostle vs.  ‘apostolic’. They do not apply in not inflection:

‘apostolic’. They do not apply in not inflection:  ‘love-

‘love- ‘apostle-

‘apostle- for

for  ‘love-letter’,

‘love-letter’,  ‘manner’ for

‘manner’ for  ‘apostle-like’.

‘apostle-like’. ‘small’. Their plural can be bisyllabic with -er:

‘small’. Their plural can be bisyllabic with -er:  , or trisyllabic with -ner:

, or trisyllabic with -ner:  . The choice varies by dialect, speaker, and item. I put these cases aside. A few other morphemes also show suppletion based on syllable count, e.g. the indicative prefix (Vaux

. The choice varies by dialect, speaker, and item. I put these cases aside. A few other morphemes also show suppletion based on syllable count, e.g. the indicative prefix (Vaux  ‘to work’.

‘to work’.  ‘dense’ vs.

‘dense’ vs.  ‘

‘ ‘to be dense’. An adjectival reading would make the compound hyponymic and take a paradoxical plural:

‘to be dense’. An adjectival reading would make the compound hyponymic and take a paradoxical plural:  xid-er, while a verbal parse would make the compound be non-hyponymic and take a transparent plural: derev-a-xid-ner. Here, the verb would be interpreted as an intransitive inchoative. I suspect that the deverbal reading is generally dominant.

xid-er, while a verbal parse would make the compound be non-hyponymic and take a transparent plural: derev-a-xid-ner. Here, the verb would be interpreted as an intransitive inchoative. I suspect that the deverbal reading is generally dominant. ‘man’.

‘man’. which usually takes the linking-vowel even before V-initial bases:

which usually takes the linking-vowel even before V-initial bases:  ‘just’ vs.

‘just’ vs.  ‘most just’ (Ēloyan

‘most just’ (Ēloyan  ‘air-ship-station (=airport)’, or the first syllable of

‘air-ship-station (=airport)’, or the first syllable of