Abstract

The future and conditional forms of venir ‘come’, tener ‘have’ and poner ‘put’ were characterized in Old Spanish by various alternatives (e.g. verné, vendré, verré, venré in the case of come.1SG.FUT) which originated through different sound changes taking place in different varieties. The victory of vendré in contemporary Spanish could be seen simply as an inconsequential resolution of this competition of forms. Here I argue against such an interpretation. I will provide quantitative geographical and diachronic evidence which suggests that the adoption of the variant vendré is related to other apparently unconnected analogical changes (most notably valo>valgo ‘be worth.1SG.PRES.IND’) in the history of the language. These two changes have conspired to align different morphological operations in a way that inflectional predictability is achieved from scratch. This development shows that predictability can be a major force in morphological change even between formally dissimilar morphological units and outside of the usual suspects the ‘morphomes’. The emergence of predictability networks like this one has important implications, touching on vital issues like segmentation, analogical change, the status of No-Blur, among others.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper starts from the observation that the Spanish verbs venir ‘come’, tener ‘have’, poner ‘put’, salir ‘exit’, and valer ‘be worth’ share various highly idiosyncratic inflectional traits: future/conditional stems in -dr- (i.e. vendré, tendré etc.), L-morphome stems in -g- (i.e. vengo, tengo etc.), and bare-stem imperatives (i.e. ven, ten etc.). These morphological operations are highly lexically restricted and almost unique to these lexical items and their derivates. This small set of verbs, thus, constitutes what has traditionally been referred to as a morphological gang.Footnote 1

This extraordinary morphological alignment is all the more surprising if one considers that these morphological operations are completely unrelated in terms of both forms and diachronic origin. The importance of morphological predictability relations has been well established by research in recent years (Ackerman and Malouf 2013; Blevins 2016, etc.). Its diachronic implications, however, have been mostly approached from the perspective of the morphome (see e.g. Maiden 2018). This means that predictability relations between formally dissimilar exponents (e.g. -dr- and -g-) have been comparatively neglected in diachronic research.

In this paper I will address this topic by analyzing the morphological changes that led to the emergence of this particular morphological alignment in Spanish. I will thus focus initially on the future forms of venir, tener, and poner in Old Spanish, which are particularly interesting because they were characterized by multiple forms (e.g. verné, vendré, verré, and venré for come.1SG.FUT) and overabundance (Thornton 2012). In Section 2, I present these forms in their historical context. After that (Section 3) I present quantitative evidence of the original geographic distribution of the different variants. Section 4 will be concerned with the subsequent prevalence of epenthetic (e.g. vendré) futures, assessing the plausibility of language contact and systemic development scenarios. Section 5 will find links to other forms and morphological changes. These will reveal some more general properties of the evolution of forms within inflectional systems, which will be discussed in Section 6. Finally, Section 7 summarizes the results and conclusions.

2 Background

The verbal morphology of Spanish and other Romance languages is complex. Verbs are arranged into several conjugations and inflect for person-number agreement and various TAMs (see Table 1).

To the forms in Table 1, one must add SG and PL imperatives (i.e. nada and nadad), and nonfinite forms (infinitive nadar, gerund nadando, and participle nadado) for a total of 53 forms. The history of most of these forms is complex and long. The youngest morphology corresponds to that of the future and conditional tenses (the two rightmost columns in Table 1). The synthetic future and conditional forms of Romance emerged, as is well known, from Latin periphrases involving an infinitive and the verb ‘have’.

The topic has sparked great interest, and literature on it is abundant (e.g. Valesio 1968; Roberts 1993; Penny 2002:205–209, etc.). The basic facts are, however, clear. Forms like Spanish nadaremos (sing.FUT.1PL) originate from Latin periphrastic constructions of the type natāre habēmus (sing.INF have.PRES.1PL). Similarly, nadaríamos (sing.COND.1PL) is derived from natāre habēbāmus (sing.INF have.IPF.1PL). The origin of these tenses was still clearly visible in Old Spanish:

-

(1)

-

(2)

As the above examples illustrate, in the earliest documented stages, certain clitics could still intervene between the infinitive and the (future or conditional) person suffixes (for details see Bouzouita 2011 and Graham 2018). This possibility was later lost as the grammaticalization process progressed (le convidarían and me querrá [cf. (1) and (2)] are the only possibility in modern Spanish). As a result of this origin, in any case, the stem upon which future and conditional forms are built nowadays resembles the infinitive or is even regularly identical to it (e.g. nadar > nadaremos ‘sing.FUT.1PL’, oler > olerías ‘smell.COND.2SG’, pedir > pediré ‘request.FUT.1SG’, etc.).

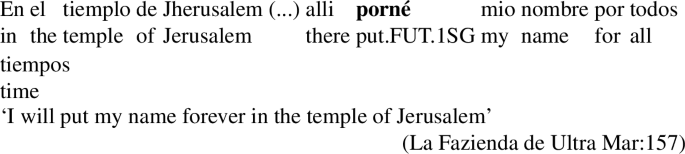

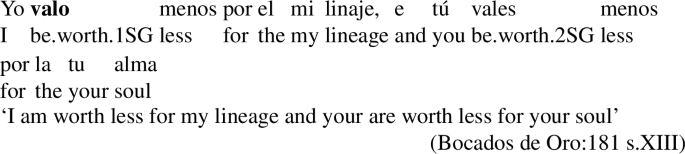

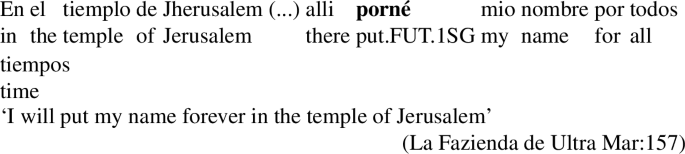

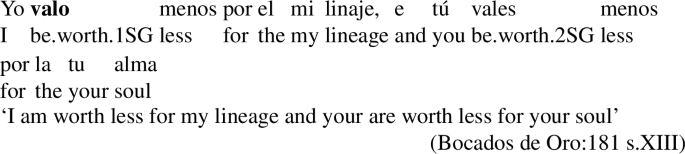

In contemporary Spanish, all verbs have a single possible stem for the formation of future and conditional forms. Older stages of Spanish (before the XVIII century), however, displayed a situation of overabundanceFootnote 2 (Thornton 2012) in the future/conditional stem of verbs like venir ‘come’, tener ‘have’ and poner ‘put’. For these verbs, this stem could alternate between vern-/tern-/porn-, vendr-/tendr-/ pondr-,verr-/terr-/porr- and venr-/tenr-/ponr-.Footnote 3 Consider the following examples (all from the XIII century) as illustrative of the variation and optionality in the use of one form or the other:

- (3)

-

(4)

-

(5)

- (6)

In (3) and (4), the same author uses different stems venr- and verr- for venir. In (5) and (6) alternative stems of poner (pondr- and porn-) are used within a single work.

On the same vein, also quite revealingly of the freedom with which the forms alternated, Nebrija (1492:64), in his grammar of the Spanish language, gave terné and ternía as the 1SG future and conditional of tener but, surprisingly, vendré and vernía as the 1SG future and conditional forms of venir. Corpus evidence suggests, however, that, despite his description, Nebrija would have also been familiar with the alternative forms tendré or verné.

This situation of free choice between the different stems is revealed with particular clarity when the competing forms are used in adjacent sentences with no difference in meaning whatsoever. The following fragment is illustrative of this:

Si predominare la flegma las comidas tengan alguna parte de calor y la purga por el consiguiente ytendramas acosidad en los ojos, ytendrase quenta que purgue humores flemagticos. Si predominare la melancholia, ternalos ojos mas pardos…(Secretos de Cirugía: 133, Pedro Arias de Benavides, 1567)

[If phlegm prevails, let meals be partly hot and the purgative too, and he will have more fluid in the eyes and it will have to be taken into account that it must purge phlegmatic states. If melancholy prevails, he will have darker eyes]

The examples of overabundance that I have been presenting, it must be noted, originate from rather different time periods (spanning from the XIII to the XVI century) and geographical locations (northwest, northeast and south of the Castilian area). This, along with the multiple forms involved suggests that the story of this competition must have been a complex one.

The verbs venir, poner and tener have a few things in common beyond the formal diversity that has concerned us so far. They are all highly-frequent (which may make them resistant to regularization) and of a very similar phonological and phonotactic profile (all of them are verbs whose stem ends in a single vowel followed by /n/). These are unmistakably the reasons behind the existence and resilience of the forms that have been mentioned throughout this section. Their identical phonotactic structure would have been responsible for the occurrence of the same sound change(s) in these verbs and their high frequency would have protected them from regularization (i.e. from a fallback to the default inflectional strategy: *tener-é, *poner-emos, *venir-ías).

On the former, it is well-known (e.g. Anderson 1965; Martínez Gil 2003) that medial unstressed vowels /e/ and /i/ in certain contexts were subject to deletion in Vulgar Latin and Ibero-Romance. This sound change, of course, affected not only the three verbs analyzed here, but also other verbs (*sabe’re > Sp. sabré ‘know.1SG.FUT’) and lexical items (Lat. comite > Sp. conde ‘count’, Lat. hominem > Sp. hombre). After the vowel deletion, two consonants came to be adjacent with differing results. Sometimes (e.g. *sa.be’re > sa’bre) the resulting sequence is tolerated, with or without resyllabification depending on the consonants involved. Some other times (e.g. ’ko.mi.te > ’kon.de, ’o.mi.nem > ’om.bre), changes followed to make the sequence acceptable (see Penny 2002:212–213, for a summary of the different solutions to different sequences). In the case of the three verbs that constitute the initial focus of this paper, they would have contained the sequence /nr/ after vowel deletion, which appears to have been particularly problematicFootnote 4 for native speakers of Old Spanish and other Iberian varieties (see Wireback 2014, 2019).

There are a few facts that suggest this. The first one is that, still in the modern language, the sequence /nr/ is almost never found except at more or less transparent morpheme boundaries (e.g. enrojecer ‘redden’, enrabietar ‘enrage’, enroque ‘castling’ etc.) or in borrowings, acronyms and proper names (e.g. inri, Enron, Conrado). Another sign that something must have felt “wrong” with the sequence /nr/ is, precisely, that, in different Iberian varieties (except in the westernmost ones like Galician-Portuguese and Asturian where it was tolerated), various independent sound changes took place that targeted those sequences, repairing them soon after they had emerged (compare Galician venres, to Spanish viernes or Catalan divendres < Lat. veneris ‘Friday’).

Different Ibero-Romance varieties, therefore, seemed to have treated sequences like the one in the 1SG.FUT (*tene’re) in different ways. Thus, the elision of medial /e/ in these contexts gave rise to different forms depending how, or whether, the resulting consonant sequence /nr/ was “repaired”. For have.FUT.1SG, for example, we find tenré (no repair), terné (metathesis), tendré (epenthesis), terré (assimilation).Footnote 5 The last three variants, thus, are straightforwardly derived from tenré and no diachronic links should be sought between them (cf. Wireback 2014).

Upon seeing this variation, therefore, one could hypothesize that the presence of tendré in contemporary Spanish could be simply due to this being the regular local evolution in Castilian (as implied, for example, by Martínez Gil 2003) or due to a more-or-less random resolution of the competition arising from this dialectal quagmire.

Literature on the topic is scarce. The few times when the prevalence of epenthetic forms has been addressed, explanations have been centred on the reasons why the forms with metathesis may have been dispreferred. Moreno Bernal (2004:153–155), thus, mentions intraparadigmatic pressures (i.e. in these forms the integrity of the stem [e.g. ten-] is jeopardized), and the disappearance of analytic constructions like the ones in (1) and (2) (so that the /r/ of the former infinite became a future suffix that everywhere else occurred immediately before the personal suffixes). Regardless of their virtues, these factors do not explain why it was epenthetic forms (i.e. tendré) that prevailed rather than, for example, the regular future-formation strategy (i.e. *teneré). Although this is not openly stated, it seems to be assumed that the form tendré was chosen simply because it was already around in the emerging dialectal melting pot.

Here, however, I will propose something quite different. Despite the notable gap in the literature (cf. Moreno Bernal 2004), I will try to show that there is indeed a story to be told about why it was tendré, vendré and pondré that prevailed in the history of Spanish. To answer this question I will present evidence in the next section of the original geographic distribution of the different forms.

3 The “old” picture: dialectal variants

An educated guess about the status of the competing forms that have been presented in Section 2 would in most cases identify these as geographical variants resulting from different sound changes occurring in different places.Footnote 6 We do seem to have regular correspondences elsewhere of the kind that the Comparative Method (Nichols 1996) relies on. Spanish seems to have /rn/ (e.g. viernes ‘Friday’, yerno ‘son-in-law’, tierno ‘tender’) where Catalan has /ndr/ (e.g. divendres, gendre, tendre) and Portuguese and Galician (also Asturian) have /nr/ (e.g. Gal. venres, genro). This correspondence is not perfect, however, not even among monomorphemic items, where morphological interferences are less likely.

Some of the seeming exceptions to this correspondence include forms like Sp. cendrar ‘to purify precious metals in an ash-based product’ < CINERĀRE, Old Spanish (h)ondrar ‘honour’ (cf. Modern Sp. honrar) < HONORĀRE, or Old Spanish pe(i)ndra ‘garment/pledge’ (cf. Modern Sp. prenda) < PIGNORA. None of the exceptions, however, seems as straightforward as the cognates showing the regular correspondences. They are much less basic (i.e. less frequent and more technical) lexical items and have a much more bumpy history in general.

Metathesis has often been described in the literature (e.g. Holt 2004) as a sporadic or capricious kind of sound change. In addition, and more specifically for the morphology analyzed here, some authors (e.g. Martínez Gil 2003:41) portray the epenthetic forms instead (vendrá, pondrá and tendrá) as the regular outcomes of sound changes in Castilian. It follows from this that, prior to any analysis of subsequent change, the original morphology of these forms would have to be clarified. A diachronic corpus of Spanish (CORDE, Corpus Diacrónico del Español) has been mined for data to settle this issue. Using the interface available at the website http://corpus.rae.es/cordenet.html, queries were made for all the different spellings of the word forms under study (see Footnote 4).

The first important point to emerge from the corpus is that the three verbs behave in all respects relevant here with remarkable similarity, which will lead me here to explore them as a single unit from now on. Consider, for example, the plot described in Fig. 1. The graphs in Fig. 1 display the use of the different stems in different periods in the history of the language (the hard numbers can be found in Tables 8 and 9 in the Appendix). It can be seen how the variation from one verb to another is insignificant compared to the one between different periods.

Between-verb variation is also negligible when it comes to the geographical distribution of the alternants. Within a single geographical location, therefore, the future morphology of poner, tener, and venir is usually approximately the same. As Fig. 2 illustrates, within a given region (also within the work of a given author), the verbs tend to show similar profiles when it comes to the proportion of use of the different stems. Thus, in the period 1550 to 1579, those with metathesis predominate in Valencia, for all three verbs, whereas those with epenthesis predominate in Toledo, also in all three verbs.Footnote 7

The verbs poner, tener and venir, thus, appear to go hand-in-hand when it comes to both geographic and diachronic variation of these competing stems. This identical behaviour is likely to be a reflection of the close association of the three verbs in the minds of language users, for whom they constitute a tightly-knit class for most inflectional purposes. Because of this behavioural similarity, the data presented here will collapse the data from the three verbs from now on.

The following map, thus, displays the geographical distributionFootnote 8 of metathesized (rn), epenthesized (ndr), assimilated (rr) and unchanged (nr) stems in the XIII and XIV centuries. Earlier texts are too scarce to provide sufficient quantitative evidence and have not been considered (see Fig. 3).

As Fig. 3 illustrates, the competing stems were subject to very clear geographic patterns originally. Very much in agreement with the political boundaries at the timeFootnote 9 and with the traditionally recognized linguistic areas, one stem is characteristic of the northeast (red), another of Navarre/La Rioja (yellow) and another one (blue) prevails in the rest of the surveyed areas. In agreement with correspondences like Cat. divendres vs. Sp. viernes, stems with epenthesis (e.g. tendré) characterized the vernacular varieties of northeast Iberia while metathesis (e.g. terné) was characteristic of the vernacular speech of Castile, the variety ancestral to modern Spanish.

Based on the geographical patterns of Fig. 3, the conclusion has to be, simply, that different sound changes (i.e. assimilation, epenthesis and metathesis) took place in different geographical areas. As far as the future/conditional forms are concerned, there is no trace whatsoever, in Castilian, of the sporadic character of metathesis, as 756 of the 759 (99,6%) forms attested from this area in the XIII and XIV centuries show the metathesized stem variant. Even taking into account the whole corpus, and considering the presence in CORDE of abundant texts from non-castilian areas and with non-castilian vernacular influences, the figures are still overwhelming (1371 out of 1815; 75.5%) in favour of the metathesized stems (see Table 9 in the Appendix).

I consider this sufficient evidence that metathesized stems like verná were the native solutions in Castilian/Old Spanish proper. The presence of the epenthesized stems (i.e. vendrá) in modern Spanish must therefore be accounted for in another way. There are two different possibilities. There must have been either i) an expansion of a “foreign” form from northeastern Iberia that gradually took over or ii) an internal systemic development of some sort (e.g. a process of morphological analogy that replaced the stems with metathesis by more transparent or predictable ones). Deciding between these two alternative (although probably not mutually exclusive) scenarios is the purpose of the next section.

4 The external influence account

To assess whether there is continuity between the epenthetic stems (i.e. tendr-, pondr- and vendr-) native to northeastern Iberia and the ones that start to appear and eventually predominate in Castilian in later periods it is necessary to investigate the geographic distribution of epenthesis in diachrony.

Thus, we can expect that, if it represents the expansion of a form from the northeast, later periods would also display the geographic biases that were detected in Fig. 3. One would expect, that is, that epenthesized stems would be ubiquitous in their original territory (i.e. Northeast Iberia) and that they would be more frequent in those areas closer to their place of origin. This, however, is not what we find at the height of the competition between the two forms (see Fig. 4).

Geographical distribution of the different stems in the years 1550 to 1579Footnote

The reason why only three decades were explored here (as opposed to two centuries for Fig. ) is that texts are simply more abundant in more recent periods. Thus, to reach a significant number of tokens (1263 geographically localizable tokens), two full centuries had to me mined in the earliest periods while three decades were enough to reach an even higher number of tokens (2103) in more recent periods. The reason for choosing the period 1550–1579 is that, as shown in Fig. , these are the years when the prevalence of the competing forms approached 50%–50%.

The map in Fig. 4 shows the distribution of stems with epenthesis (e.g. tendré, in red) and with metathesis (e.g. porné, in blue) between the years 1550 and 1579. As Fig. 4 reveals, at the height of the competition between the two stems, there appears to be no trace whatsoever of any hypothetical northeastern origin for the epenthesized stems. These seem to be especially frequent in the north and in smaller isolated pockets throughout Iberia in a way that seems to lack much geographic structure.

Other competing stems were already absent from the competition illustrated in Fig. 4. It is worth mentioning that stems with assimilation (e.g. verré) or with no change (e.g. venré) disappear very fast (see Fig. 5) with the adoption of Castilian as the national language of the soon-to-be-united Spain. Very importantly, however, at exactly the same time (i.e. in the first half of the 15th century) we also observe a very substantial drop in the frequency of epenthetic stems from 23.2% N = 199 to 4.3% N = 72 between the XIV century and the first half of the XV century. This suggests that, at the time, epenthetic stems were regional forms which, much like stems with assimilation (which undergo a comparable drop at the time), were foreign to Castilian proper and largely on their way out of the language. The diachronic profile shown in Fig. 5, thus, provides further evidence for a discontinuity between the “old” tendrá, pondrá and vendrá that originated regularly from sound change in northeastern Iberian varieties and the “new” tendrá, pondrá and vendrá that emerged and multiplied systemically (i.e. by morphological analogy) in Castilian in later periods.

There seems to be, therefore, enough evidence that the presence in contemporary Spanish of the future/conditional stems tendr-, pondr- and vendr- is not the result of regular sound change in Castilian and that it is also probably not due to contact with neighbouring Iberian varieties. My conclusion, therefore, has to be that we are dealing with an instance of morphological analogy internal to the language.

There are a few verbs in Spanish which show a future/conditional stem in -dr- from the earliest records and which could have provided the model for a traditional proportional analogy. This is the case, for example, of the contemporary Spanish verb salir > saldrá ‘exit’. Other verbs used to form their future stem in the same way in Old Spanish (e.g. doler > doldrá ‘hurt’ or moler > moldrá ‘grind’). Notice how in this case, all the stems are of a form vowel + /l/. Epenthesis, thus, seems to have been the regular Castilian “repair” of those /lr/ sequences arising from the deletion of medial unstressed vowels while metathesis would have been the preferred repair for the sequence /nr/. Be that as it may, the analogical relation to those verbs could be represented in this way:

Model | sal-ir (INF) > sal-dr-á (3SG.FUT) |

Outcome | ven-ir (INF) > ? > ven-dr-á |

A “normal” analogical change on the basis of these verbs, however, seems to me unlikely given that the verbs tener, poner and venir are all very frequent, much more so than the (small) group of verbs with an original future/conditional stem in -dr-, whose only frequent member (around half as frequent nonetheless as tener, poner, and venir, see Appendix) was salir.

On the basis of their high frequency and their formation of a small but close-knit class, terná, porná and verná seem to me to have had in principle a strong enough foothold in Castilian to be able to resist the levelling forces of analogy and eventual diachronic obliteration. Even if they had perished, an analogy with the regular strategy for the formation of the future/conditional stem (i.e. with med-ir > med-ir-á ‘measure’, ol-er > ol-er-á ‘smell’ etc.) seems at first sight to have been the only other morphological operation with enough weight (i.e. type and token frequency) to have constituted the basis for a hypothetical analogical change. It is, therefore, necessary, to identify which morphological forces were at play to make change “preferable” to the preservation of the statu quo and change to an irregular, infrequent morphological marking “preferable” to mere regularization (i.e. terná > tenerá).

5 Other paradigmatic observations: the stem augment in -g

The different parts of an inflectional system are all interconnected to a greater or smaller extent. Thus, when explaining concrete morphological changes (e.g. FUT terné > tendré), it may be necessary to refer to other forms and tenses. This section will present the morphology most intimately linked to the irregular future-conditional forms in -dr-.

As advanced in the introduction, the class of verbs that in contemporary Spanish forms the future/conditional stem with a -dr- augment is a small, 5-member one, formed by salir, valer, tener, poner and venir (plus their derivates, e.g. atener, deponer, convenir etc.). The inflectional paradigms of these verbs, however, show some important similarities besides this one. A morphological quirk that characterizes the members of this class, for example, is that they form their 2SG imperative with the bare stem (or with a zero morpheme if you prefer). In this way we have imperative forms sal, val,Footnote 11ten, pon and ven. Only one other lexical item in Spanish (the verb hacer) uses this same zero imperative.

Another remarkable inflectional property that all these verbs have in common is that they have another stem augment (in this case of the form -g-) in the 1SG present indicative and throughout the present subjunctive. Thus, the 3SG present subjunctive of these verbs is sal-g-a, val-g-a, ten-g-a, pon-g-a and ven-g-a. This shared property becomes all the more remarkable when one takes into account that this morphological operation is also, like the -dr- augment in the future/conditional, exclusive to these five verbs.Footnote 12

It must be kept in mind that, despite its application to the exact same lexemes in contemporary Spanish, the historical origin of the -g- augment is entirely unrelated to that of the -dr- augment of the future/conditional (see Table 2).

The origin of the stem alternations like the one of sal-ir/salg-o is to be found in the paradigmatic distribution of suffixes starting with front (/e/, /i/) or back vowels (/a/, /o/, /u/) in the ancestral paradigm. There were two independent sound changes in early Romance which, in conjunction with the aforementioned suffixes, resulted in stem alternations with the same ‘inverted-L’ shape in the paradigm (see e.g. Maiden 2018:85).

The first one consisted in the palatalization of velar consonants before front vowels (see *diko in Table 2). The second one consisted in the palatalization of certain consonants (e.g. /l/) before /j/, after which the yod was lost (see *saljo in Table 2). Because front vowels and yod were in complementary distribution in Romance, the paradigmatic extension of the alternations created by the two sound changes was identical.

Because of a later sound change in Spanish that voiced voiceless plosives between vowels (e.g. /diko/>/digo/), a few very frequent verbs (e.g. decir ‘say’ and hacer ‘do’) ended up characterized by a /g/-final stem in the 1SG.PRES.IND and in the PRES.SBJV cells. This fact must have provided the model for later analogical processes, which tended to generalize this /g/ as the default marking of this stem alternation pattern in most other verbs. This /g/ was often introduced, for example, in place of the palatalized stem that had resulted from the sound change /lj/>/ʎ/. This happened very early (before documented periods) in the case of salir ‘exit’ where, as we say, forms like *saʎ-o were replaced by salg-o analogically.

Considering the entirely different historical origin of the two forms (-g- vs -dr-) and the size of the Spanish verbal lexicon, it would be almost impossible for the two forms to appear in the exact same lexical items by chance. This extraordinary alignment of morphological operations in the modern language is, indeed, not a matter of historical accident, but rather is the result of several (at first sight unrelated) processes of morphological analogy. One of them is the one this paper started with, namely, the change of terné, porné and verné to tendré, pondré and vendré. Another one is the extension of the -g- augment to the verb valer ‘be worth’, which in Old Spanish was conjugated regularly in this respect (i.e. without an augment: valo, vala etc.). A third one must have occurred, unfortunately, in the undocumented stages of the evolution from Latin to Old Spanish and would have consisted of some changes to imperative forms (e.g. *tjen > ten, see Rini 2014). Whereas it may be impossible to obtain more information about this last analogical change, the one in valer occurred, fortunately enough, within the documented stages of Spanish and can therefore be investigated in depth, in terms of both its geographic and diachronic profiles. Consider the map in Fig. 6.

As I already advanced before, the stem used in the 1SG present indicative and through the present subjunctive was overwhelmingly the regular val- in the earliest documented stages of the language, which contradicts some previous claims.Footnote 13 Here are a few examples of such use:

-

(7)

- (8)

Between 1200 and 1399, 1762 out of 1870 occurrences of these forms (94%) show the regular form of the stem val- (i.e. valo, vala, valas...). What is more revealing, however, is the geographical distribution of the alternative stem valg-. As illustrated in Fig. 6, this alternative is found to be predominant in the northeast, precisely those areas where the forms for the future/conditional were predominantly tendr-, pondr- and vendr- in the same period (see Fig. 3).

As I showed in earlier sections, those forms with epenthesis after /Vn/ were the regular outcomes of sound change in the Romance varieties (Aragonese and Catalan) spoken in the northeast. There is, however, nothing regular about the presence of the stem valg- in those same areas or its absence from Castilian varieties.Footnote 14 I take this co-occurrence of the -dr- and -g- augments of the stem to be therefore non-accidental.

Another important piece of evidence can be presented, however, to persuade the reader about this respect. This is the diachronic coincidence in Spanish of the analogical changes of the type tern-á > tendr-á and of val-o > valg-o. Consider the S-curves of the two changes (see Fig. 7).

As Fig. 7 shows, the timing of the two morphological changes in Castilian coincided in the temporal axis to a very high degree. To be more specific, the progression of the first change (val- > valg-) preceded the second (tern- etc. > tendr- etc.) by only a few decades at the time when change was fastest (i.e. around 1550). The S-curves for both changes start to get off the ground in the late XV century. The two innovative forms advance very fast during the XVI century and the changes reach near completion by the first decades of the XVII century.

I believe that the notable diachronic alignment of the two changes, added to the extraordinary geographic overlap between a -g- augment in valer and the -dr- future/conditionals in tener, poner and venir, suggests that there is a dependency relation of some sort between the two seemingly unrelated forms. The next section will be devoted to understanding the nature and raison d’être of this relationship.

6 Discussion

There is a vast literature around the morphological entity or paradigmatic phenomenon that is usually labelled ‘morphome’ since Aronoff (1994). This term usually refers to patterns of formal identity within the inflectional paradigm of a lexeme that have to be regarded as arbitrary (or as morphologically stipulated if you will) because they do not correspond to semantic distinctions and are not reducible to phonological context either.

Although morphomes are not exclusive to Romance (see e.g. Saami in Herce 2020), it is this family of languages that has inspired most of the literature (e.g. Maiden 2005, 2018; O’Neill 2011, etc.). Some of the forms that this paper has dealt with are specific instances of the ones that are often discussed in morphomic literature. The -g- augment, for example, is an instance of what is usually referred to as the L-pattern or the L-morphome while the -dr- augment characterizes the future/conditional, another (albeit more debatable) morphome (see e.g. Esher 2012). Consider the paradigmatic distribution of the two forms (see Table 3).

In principle, the paradigm cells that share the augment -g- and (arguably) those that share the augment -dr- share nothing beyond those forms themselves. They are, thus, purely morphological (but highly systematic) grammatical entities. Research around the morphome (most notably by Maiden) has shown how these paradigmatic affinities, despite not serving any discernible communicative purpose, can be highly resilient in language history and even provide a model for analogical change.

There is a basic consensus in the literature (e.g. Blevins 2016:106) that morphomes owe their productivity to the predictive relations that they afford. Thus, because the stem alternations in hundreds of Spanish verbs (e.g. caigo/caes, hago/haces, nazco/naces, quepo/cabes, etc.) share the same paradigmatic distribution as that of valgo/vales, the use of a particular stem alternant in any of the morphosyntactic values that the morphome spans allows the language user to predict that the same stem is going to be used in all the other cells too. Consider the paradigms in Table 4.

Because the pattern is the same across hundreds of lexemes, the form naθka ‘be born.SBJV.3SG’ predicts the infrequent naθko ‘be born.IND.1SG’ and vice versa. Even in the presence of a bias in favour of one-to-one mappings between form and meaning, these structures could resist analogical forces thanks to the existence of these predictive relations. In this way, and even though the form naθko ‘I am born’ is extremely infrequent in naturalistic input, it can resist a hypothetical analogical leveling to *naθo (which would align form to mood distinctions) because such a development would disrupt/undermine predictability at the level of the whole inflectional system. If some verbs had a different stem alternant limited to the present subjunctive and others had the original present subjunctive + 1SG present indicative instead, the predictions mentioned earlier in this paragraph would not hold.

One could also think, of course, of a massive morphological change of the form salgo > *salo, kepo > *kabo, naθko > *naθo etc. If every single lexical item changed in this way, predictive relations would still hold and form would have been aligned to semantic mood distinctions. Changing the paradigmatic distribution of stem alternation in hundreds of lexemes, including some very frequent ones, in one fell swoop, however, seems to be an impossible development given the sneakiness that usually characterizes language change.

Using a metaphor borrowed from evolutionary biology (e.g. Dawkins 1997), it is as if Spanish were trapped in this respect in a less-than optimal summit from which it cannot reach a more optimal design (i.e. form-function isomorphy) because it would have to get worse (i.e. less adapted because of the drop in predictability) before it could get any better. The inability to remember every single form ever heard and the necessity to produce forms that have never appeared in the input before (see the Paradigm Cell-Filling Problem of Ackerman et al. 2009) forces speakers to adhere to predictiveness relations even when these run contrary to communicative concerns.

This is, thus, the raison d’être of morphomes and there is by and large consensus around this point. However, there is an important further point to be made about the relationship of forms and predictability which is often neglected in morphomic literature. Predictability relations may be signalled/perceived with special pristineness between paradigm cells that share some form (e.g. /g/ between val-g-o and val-g-áis) but they also occur between cells that have entirely different forms (e.g. between val-g-o and val-dr-ían). Because, as has been mentioned before, the -g- and the -dr- stem augments occur in the exact same verbs in contemporary Spanish, the presence of the former in any of the cells of the L-morphome (i.e. 1SG.PRES.IND+PRES.SBJV) predicts the presence of the latter in all of the cells of the future and the conditional and vice versa.

That predictability relations can occur both in the presence and in the absence of formal identity is well known in synchronic studies (e.g. Stump and Finkel 2013; Ackerman and Malouf 2013) but the diachronic ramifications of this remain largely unexplored. Literature on the diachrony of morphological affinities has focused on the emergence and preservation of morphological structure and predictability that involves systematic formal identities (morphomes like the one in Table 4), rather than systematic differences. These morphomes (see e.g. Maiden 2018) often emerge in one fell swoop as a result of sound change that affects a set of cells or word forms but not others. Research has thus focused on showing how these morphological affinities are defended against potentially disrupting developments.

In contrast to this, the present paper analyzes the emergence of a very different type of morphological structure (a morphological gang, see Fehringer 2003) that involves diachronically unrelated morphological operations gradually gravitating toward an identical set of lexemes. The improvement of predictability relations between morphological elements can, therefore, constitute a major driving force in analogical change, even in the absence of formal affinity between the predictor and the predicted.

Before the analogical changes analyzed here (see the left of Table 5), the -g- and -dr- augments of the stem cross-classified in the lexicon. Because of this, the two forms combined to distinguish a total of 3 lexical classes: one with -g- but without -dr- (e.g. tener), one with both -g- and -dr- (e.g. salir), and one with -dr- but not -g- (e.g. valer). This is a functionally superfluous source of morphological complexity.

Predictability relations can be measured in terms of (conditional) entropy (see Ackerman and Malouf 2013, for details on this measure, its calculus and its application to morphology). For the above set of lexemes and forms, the L-exponent has an entropy of 0.99 (it is almost a choice between two equiprobable suffixes), and that of the FUT/COND exponent is 1.58 (a choice between 3 equiprobable suffixes). The conditional entropy of the L-exponent given a FUT/COND with -dr- is 0.92, and that of the FUT/COND given an L-exponent in -g- is 0.81. The fact that perfect predictability (i.e. entropy = 0) does not hold between these exponents is expected from the completely unrelated origin of the two forms.

After the changes of the XV and XVI century (right side of Table 5), however, the inflectional system has been streamlined. The two stem augments do no longer cross-classify but rather have identical distributions in the lexicon. As a result, the two forms are now only responsible for a single lexical class (see the notion of “reinforcement” in Enger (2014)) and are thus completely predictive of one another. The entropy of L- and FUT/COND exponents is 0.99. The loss of metathesis as a strategy has improved predictability of FUT/COND. Conditional entropies of the L-form on the basis of a FUT/COND in -dr-, and of the FUT/COND form on the basis of an L-morphome in -g- are now 0. Whereas before the change no absolute prediction could be made in any of the two directions, the suffixes -g- and -dr- have now become completely predictable from one another.

Although the phenomena analyzed here come from a restricted set of lexemes in Spanish,Footnote 15 they have important ramifications for morphological theory. Most of the literature on the morphome, for example, has identified these as units of predictive value. For example, Blevins (2016:106), who is otherwise somewhat skeptical of the notion as usually defined, mentions that “morphomic patterns (…) provide a pure expression of predictive relations”. However, it becomes clear from the pattern g⇔dr that perfect predictability relations can exist outside of the domain of the morphome. Furthermore, I have shown how language change strives to create these relations even in the absence of formal similarity.Footnote 16 The purest expression of predictive relations must then surely be sought outside morphomes as traditionally defined. If predictive relations can hold in the absence of formal affinity, the formal identity that the morphome requires is a decisively confounding factor. It is thus not implausible to think that formal identity may draw attention to certain predictive relations over others.

Another point of interest to the morphologist is the link that the analogical processes analyzed here establish between two very different grammatical entities. Morphomes are most usually conceived of and investigated as self-standing morphological units, that is, as if they were basically independent from other forms in the paradigm and from other morphomes. The few times when the interaction between different morphomes is discussed (Herce 2019), this interaction involves formal elements “jumping” from one to the other, such as when the -g- augment spreads to the past tense in Catalan (e.g. Wheeler 2011; O’Neill 2018) or when some past root spreads to the present in a variety of Asturian (Maiden 2012). The alignment of the -g- and the -dr- augments in Spanish, however, illustrates that the interaction between different morphomes does not necessarily involve the borrowing of forms. Two morphomes have been shown here to be “talking” to each other in a way that has been little explored in the literature, thus offering plenty of avenues for future research.

The last point to reflect on concerns the relevance of these findings for our broadest assumptions in theoretical morphology. The reader may have noticed by now that there is a very particular characteristic shared by the forms (-g- and -dr-) that have become aligned in the Spanish lexicon, which is that they are both segmentable morphological elements. Even if these forms have usually been conceptualized as part of the stem (and thus as not very different from the /g/ in haga or the /dr/ in podrá, see Footnote 6) it is clear that, within the present class of verbs, those forms are distributionally indistinguishable from suffixes. The analogical changes that have been investigated here, therefore, seem to have aligned morphological operations (i.e. ‘add /g/’ and ‘add /dr/’) rather than merely forms. We thus see no analogical drive to create forms like *hadrá on the basis of haga or *didrá on the basis of digo. This may lend some support to constructive approaches to morphology, as we see that language users appear to be sensitive to such issues like segmentability in this particular case.

On a related topic, these analogical changes in Spanish may also prove interesting in relation to Carstairs-McCarthy’s (1994) No-Blur Principle. According to this hypothesized constraint of morphological architecture, inflectional affixes have to either apply to a single inflection class or else constitute defaults. Before the analogical changes surveyed here, the forms -g- and -dr- did not obey the principle, as neither of them was confined to a single class nor were the default (see Table 6).

After the changes, however, three classes have effectively merged into one regarding the inflectional aspects analyzed here (i.e. stem augments). As a result, both -g- and -dr- have become unique to their class in the modern language and have thus come obey No-Blur (see Table 7).

Previous alleged interactions of morphomes and No-Blur have been of a very different kind. In Maiden (2007) we see how morphomes (metamorphomes like PYTA) can provide a valid niche for affixes in terms of adhering to No-Blur within a paradigm. In the case of the presently analyzed forms, it is the exponents of morphomes (i.e. meromoprhomes) that have changed their lexical distribution in a way in which they come to obey No-Blur.

If No-Blur were indeed grounded in a cognitive preference of our species and if it constituted a desirable trait in the organization of inflectional systems, this could have provided the motivating factor for the morphological changes that have been analyzed in this paper. It has to be stressed, however, that No-Blur is, of course, intimately linked with inflectional predictability in general. As shown by Ackerman and Malouf (2015), inflectional configurations that obey the No-Blur Principle could emerge simply from speakers’ more general needs to predict inflectional forms from other forms. It would thus be interesting to investigate whether attested morphological changes resemble this one (i.e. result in configurations that abide by No-Blur) or can instead achieve a reduction of conditional entropy by other means.

7 Conclusion

This paper has presented quantitative diachronic and geographic evidence that points towards the interdependence of two rather different analogical changes in the history of Spanish. The first one concerned the extension of the form -dr- to the future and conditional tenses of the verbs tener, poner and venir. The second consisted of the irruption of the form -g- into the 1SG present indicative and into the present subjunctive of the verb valer. The almost identical geographical spread of the two forms, combined with their rise in Castilian at almost the exact same time, suggests that despite their completely different phonological makeup and paradigmatic distribution, the two elements are somehow systemically connected.

This connection is to be found, I argue, in inflectional predictability. Through the combined effect of the two changes, two erstwhile totally independent and unrelated morphological elements have come to be characteristic in the modern language of the exact same five lexical items. This is a simplifying development that has established predictability relations from scratch between formally dissimilar units. The analogical forces identified here have operated both across forms and across inflectional domains in a way that, to my knowledge, has not been discussed in the literature so far. These developments, however, are very relevant to the field because they raise questions in connection to some of our most important morphological assumptions. If shared form is not required for predictability relations to hold or to constitute a driving force for analogical change this may challenge one of the main definitional tenets of the morphome. However, of course, it would open the floor to investigation in an area of research that has received comparatively little attention.

Notes

I thank an anonymous reviewer for drawing my attention to this term.

The term ‘overabundance’ (also ‘inflectional doublet’) refers to a situation whereby a given morphosyntactic value can be expressed by different forms. Thus, in a cell or group of cells in a paradigm, two or more forms coexist as possible synonymous options for the speaker to choose from. For many speakers, for example, both ‘learned’ and ‘learnt’ are possible as the past tense form of ‘learn’.

I am going to refer throughout this paper to forms like tendr-, pondr- or vern- (also pong- or valg-) as ‘stems’. This, however, is mostly to adhere to terminological tradition (e.g. Maiden 1992; Anderson 2013) and should not be understood as a claim on my part that these are indivisible morphological units.

This does not mean that other sequences were not equally problematic. For example, the sequence /mn/ that emerged in words like hominem ‘man’, sēmināre ‘seed’, *nōmine ‘name’, *famine ‘hunger’ etc. was also frequently repaired in various different ways. For example, all of nomne, nome, nomre, nombre, and nompne are found for ‘name’ in older texts. Different variants were sometimes also used interchangeably right by each other.

Spelling variants translate straightforwardly in most cases to phonological forms: tenré /ten’re/, terné /ter’ne/, tendré /ten’dre/, terré /te’re/. Accentuation and other minor orthographic conventions (e.g. spelling “u” or “v” for /β/, “j” or “i” for /j/ etc.) are not always systematic in the earliest periods and so, for example, vendré, uendré, vendre, and uendre are all possible spellings for the same phonological form, a fact which has been taken into account here.

Cognate words with different phonological correspondences (e.g. Sp. ju[g]ar vs It. gio[k]are ‘play’) usually correspond to different evolutions of a word in different geographical areas. It is logically possible for different communities to develop different daughter languages in the same geographical area (with different sound changes applying, for example, along some diastratic divide in a diglossic situation) but I believe it should still be our null hypothesis that we are dealing with geographically-determined variants.

These two provinces are shown because of their high number of tokens from all 3 verbs and because of their quite different overall profiles, with Toledo leaning towards epenthesis and Valencia towards metathesis.

Those anonymous texts which are impossible to assign to any concrete region have been excluded. These represent 30.4% of the tokens in this period and 53.1% of the tokens in the period 1550–1579 (see Fig. 4). The remaining forms (i.e. those which can be linked to some geographic location either by place of birth of the author or by place of writing of the text) have been grouped by province. Only provinces with three or more data points have been represented.

Consider the geographical extent of the ancient kingdoms of Castille, Aragon, and Navarre, which roughly corresponded to the blue, red, and yellow areas, respectively, in the map.

The reason why only three decades were explored here (as opposed to two centuries for Fig. ) is that texts are simply more abundant in more recent periods. Thus, to reach a significant number of tokens (1263 geographically localizable tokens), two full centuries had to me mined in the earliest periods while three decades were enough to reach an even higher number of tokens (2103) in more recent periods. The reason for choosing the period 1550–1579 is that, as shown in Fig. , these are the years when the prevalence of the competing forms approached 50%–50%.

The 2SG imperative form of valer is somewhat uncertain. Most modern prescriptive standards, like the one of Real Academia Española (2018) propose vale, but this is seldom found. The form val was provided instead by Nebrija (1492) in his grammar. Other sources like Becker (1999:126) give the two forms as valid. In my opinion, the most accurate description would present this verb as lacking a 2SG imperative form, since both forms seem infelicitous to most speakers. The semantics of the verb, of course, do not help to make imperative forms frequent in natural speech but the ill-formedness of *val or *vale cannot be accounted for just semantically, since the plural imperative valed is unproblematic. It seems to be, therefore, a genuine case of defectiveness, caused by the plausible applicability of two different rules/schemas to build this particular form, added to the absence of evidence in the linguistic input.

There are a few verbs (e.g. asir and yacer) whose conjugation may (optionally) show a -g- augment according to prescriptive standards (i.e. asga, yazga). These have not been included here. Because of their extremely infrequent occurrence (below 0.05 per million words) and their learned status I don’t consider them to be an active part of the verbal inflection system of contemporary Spanish.

Note that segmentation is important in determining the shape of morphological operations as defined here. The form podrá (can.3SG.FUT), for example, contains the sequence /dr/ but, crucially, cannot be equated with forms like vendrá because its relation to other forms of its paradigm is different. Thus, the opposition venir-vendrá-vendré allows us to segment the second as ven-dr-á, whereas the paradigm of poder-podrá-podré would only support a segmentation pod-r-á. This is the reason why poder has not been considered here to form its future/conditional with a -dr- augment like venir.

The same reasoning applies to forms like caiga (fall.3SG.SBJV) or haga (do.3SG.SBJV). The verbs caer and hacer, like venir, show /g/ throughout the 1SG.PRES.IND and the PRES.SBJV cells of their paradigm. Closer inspection would reveal, however, that caer-caiga-caigo only supports a segmentation ca-ig-a (i.e. no -g- but -ig- augment) and that the relationship between venir and venga is not the same as that of hacer and haga, since in the second pair, -g- is replacive (i.e. is incompatible with the final segment /θ/ of the infinitive stem) rather than constitutive of a segmentable augment to the infinitive stem.

Maiden (2018:113), for example, claims that in Old Spanish the verb valer was inflected with a velar extension: valgo valga valgas etc. In the light of the corpus data I present here this was not generally the case.

There are numerous studies (e.g. Penny 2002:174; O’Neill 2012) but almost complete uncertainty concerning the behaviour and relative diachrony of the loss of yod in different conjugations and stem-final consonant palatalization in Ibero-Romance. Analogical changes in the paradigm have blurred the original stem alternations in the different varieties. Although Galician and Portuguese have va[ʎ]o, any story in which the contemporary Spanish forms valg- are presented as straightforward continuants of a palatalized stem alternant in earlier Romance would be ad hoc, since comparable verbs from the second conjugation like oler ‘smell’ or doler ‘hurt’ do not show it and, most importantly, it would be contradicted by the textual evidence presented in Fig. 6.

This is not necessarily a shortcoming. I fully agree with Joseph (1997:159) that most language users’ generalizations “should be recognized as being truly local in nature, that is, they have a restricted scope, and where linguists’ generalizations go astray is in not being sufficiently localized”.

There is diachronic evidence that already before the morphological changes that concern us in this paper, these verbs had already been gravitating towards the same inflectional patterns. Thus, as mentioned before, they all have nowadays bare-stem imperatives: ten, ven, sal etc. Whatever the exact phonological context was that facilitated apocope, it should have applied in many other word-forms and verbs as well (see Luquet 1992), however, only the imperative of our small gang of verbs kept this trait.

Similarly, the absence of diphthongization in 2SG.IMP ten < tenē is completely unexpected and must have emerged analogically on the basis of ven < venī and pon < pōne where it would have been regularly absent. Note also that, whereas the stem of veniō would have developed L-stem alternation (/nj/>/ɲ/), that of pōnō should not have had alternation at all. All in all, various independent morphological changes can be identified in the history of Spanish whose outcome is to align the inflections of the set of verbs discussed in this paper.

References

Ackerman, F., Blevins, J. P., & Malouf, R. (2009). Parts and wholes: Implicative patterns in inflectional paradigms. In J. Blevins & J. Blevins (Eds.), Analogy in grammar: Form and acquisition (pp. 54–82). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ackerman, F., & Malouf, R. (2013). Morphological organization: The low conditional entropy conjecture. Language, 89(3), 429–464.

Ackerman, F., & Malouf, R. (2015). The No Blur Principle effects as an emergent property of language systems. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 41.

Anderson, J. M. (1965). A study of syncope in Vulgar Latin. Word, 21(1), 70–85.

Anderson, S. R. (2013). Stem alternation in Swiss Rumantsch. In S. Cruschina, M. Maiden, & J. C. Smith (Eds.), The boundaries of pure morphology: Diachronic and synchronic perspectives, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aronoff, M. (1994). Morphology by itself: Stems and inflectional classes. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press.

Becker, I. (1999). Manual de español: gramática y ejercicios de aplicación; lecturas; correspondencia; vocabularios; antología poética. São Paulo: Nobel.

Blevins, J. P. (2016). Word and paradigm morphology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bouzouita, M. (2011). Future constructions in medieval Spanish: Mesoclisis uncovered. In Kempson et al. (Eds.), The dynamics of lexical interfaces (pp. 91–132). Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Carstairs-McCarthy, A. (1994). Inflection classes, gender, and the principle of contrast. Language, 70(4), 737–788.

Dawkins, R. (1997). Climbing mount improbable. New York: WW Norton & Company.

Enger, H.-O. (2014). Reinforcement in inflection classes: two cues may be better than one. Word Structure, 7, 153–181.

Esher, L. (2012). Future, conditional and autonomous morphology in Occitan. DPhil., University of Oxford.

Fehringer, C. (2003). Morphological ‘gangs’: constraints on paradigmatic relations in analogical change. In Yearbook of morphology 2003 (pp. 249–272). Berlin: Springer.

Graham, L. A. (2018). An analysis of morphosyntactic variation in the Old Spanish future and conditional. Journal of Historical Linguistics, 8(2), 192–229.

Herce, B. (2019). Morphome interactions. Morphology, 29(1), 109–132.

Herce, B. (2020). On morphemes and morphomes: exploring the distinction. Word Structure, 13(1).

Holt, D. E. (2004). Optimization of syllable contact in Old Spanish via the sporadic sound change metathesis. Probus, 16(1), 43–61.

Joseph, B. D. (1997). How general are our generalizations? What speakers actually know and what they actually do. In A. D. Green & V. Motopanyane (Eds.), Proceedings of the thirteenth eastern states conference on linguistics (pp. 148–160). Ithaca: Cascadilla Press.

Luquet, G. (1992). De la apócope verbal en castellano antiguo (formas indicativas e imperativas). In M. Ariza Viguera (Ed.), Actas del II congreso internacional de historia de la lengua española (pp. 595–604). Pabellón de España.

Maiden, M. (1992). Irregularity as a determinant of morphological change. Journal of Linguistics, 28(2), 285–312.

Maiden, M. (2005). Morphological autonomy and diachrony. Yearbook of Morphology 2004, 137–175.

Maiden, M. (2007). Blur avoidance and Romanian verb endings. In A. Lahiri, J. Meinschaefer, & C. Schwarze (Eds.), Documentation of the workshop formal and semantic constraints in morphology (pp. 92–101). KOPS.

Maiden, M. (2012). A paradox? The morphological history of the Romance present. In S. Gaglia & M.-O. Hinzelin (Eds.), Inflection and word formation in Romance languages 186. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Maiden, M. (2018). The Romance verb: Morphomic structure and diachrony. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Martínez Gil, F. (2003). Consonant intrusion in heterosyllabic consonant-liquid clusters in Old Spanish and Old French. In R. Núñez-Cedeño, L. López, & R. Cameron (Eds.), A Romance perspective on language knowledge and use: Selected papers from the 31st linguistic symposium on Romance languages, Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Moreno Bernal, J. (2004). La morfología de los futuros románicos. Las formas con metátesis. Revista de filología románica, 21, 121–169.

Nebrija, A. de 1492. Gramática Castellana. In A. Quilis (Ed.). Madrid: Editora Nacional [1980]

Nichols, J. (1996). The comparative method as heuristic. In M. Durie & M. Ross (Eds.), The comparative method reviewed: Regularity and irregularity in language change (pp. 39–71). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

O’Neill, P. (2011). The Ibero-Romance verb: allomorphy and the notion of the morphome. PhD dissertation, Oxford University.

O’Neill, P. (2012). New perspectives on the effects of yod in Ibero-Romance. Bulletin of Spanish Studies, 89(5), 665–697.

O’Neill, P. (2018). Velar allomorphy in Ibero-Romance. Studies in Historical Ibero-Romance Morpho-Syntax, 16, 13–43.

Penny, R. (2002). A history of the Spanish language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Real Academia Española: Banco de datos (CORDE) [online]. Corpus diacrónico del español. http://www.rae.es [accessed June-September 2018].

Rini, J. (2014). Un nuevo analisis de la evolucion de los imperativos singulares irregulares di, haz, ve, se, ven, ten, pon, sal, (val). Zeitschrift fur romanische Philologie, 130(2), 430–451.

Roberts, I. (1993). A formal account of grammaticalisation in the history of Romance Futures. Folia Linguistica Historica, 13, 219–258.

Stump, G., & Finkel, R. A. (2013). Morphological typology: From word to paradigm (Vol. 138). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thornton, A. M. (2012). Reduction and maintenance of overabundance. A case study on Italian verb paradigms. Word Structure, 5(2), 183–207.

Valesio, P. (1968). The Romance synthetic future pattern and its first attestations. Lingua, 20, 113–161.

Wheeler, M. W. (2011). The evolution of a morphome in Catalan verb inflection. In M. Maiden et al. (Eds.), Morphological autonomy: Perspectives from romance inflectional morphology (pp. 183–209).

Wireback, K. J. (2014). On syncope, metathesis, and the development of /nVr/ from Latin to Old Spanish. Bulletin of Hispanic Studies, 91(6), 559–580.

Wireback, K. J. (2019). On grammaticalization and the development of Latin /nV̆r/ in Spanish, Portuguese, and other varieties of Western Romance. In G. Rei-Doval & F. Tejedo-Herrero (Eds.), Lusophone, Galician, and Hispanic linguistics: Bridging frames and traditions.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Matthew Baerman, Oliver Bond, Louise Esher, and Iván Igartua for their comments on earlier versions of this paper. I also would like to thank Ana Luís and two anonymous reviewers for insights and assistance that have improved this manuscript. Finally, the financial support of TECHNE and the Basque Government (PRE_2015_1_0175) are also gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Tables 8 and 9 contain the number of tokens in CORDE of the various future/conditional stems (‘ndr’, ‘rn’, ‘rr’ and ‘nr’) in different verbs (poner, tener, venir) for various time periods (XIV century, 1450–1499, 1550–1579 and 1600–1619) and geographical regions (Valencia vs Toledo).

Table 10 contains the number of tokens in CORDE of the various types of future stems (‘rn’, ‘ndr’, ‘rr’ and ‘nr’) of poner, tener and venir, the number of tokens of the val- vs valg- stems of valer, and the tokens of the saldr- and salg- stems of salir for various periods in Spain.

Table 11 contains information on the geographical distribution of the various future-conditional stems (‘rn’, ‘ndr’, ‘rr’ and ‘nr’) of poner, tener and venir and of the val- vs valg- stems of valer in different periods.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Herce, B. Alignment of forms in Spanish verbal inflection: the gang poner, tener, venir, salir, valer as a window into the nature of paradigmatic analogy and predictability. Morphology 30, 91–115 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-020-09352-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-020-09352-8