Abstract

This article aims at investigating the linguistic criteria to determine what a word is in Wichi (Matacoan), a polysynthetic and agglutinative language spoken in the Gran Chaco Region, in South America. The main phonological criteria proposed are phonological rules and stress. We also apply some grammatical criteria that have been proposed cross linguistically, some of which are useful to determine the boundaries of grammatical words in Wichi. Finally, we explore the relationship between the phonological and grammatical word with the written word. We base our analysis of written words on a textbook (Tsalanawu) used in many bilingual schools in Northeastern Argentina.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The 2006 version is an adaptation of the 1996 into a different Wichi dialect. It also contains innovative pedagogical material. The 2006 version was published as part of the Documentation Program of Endangered languages (DOBES) sponsored by the Volkswagen Foundation and directed by Lucía Golluscio.

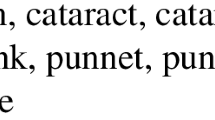

We decide to provide examples from these two dialects because they do not exhibit many dialectal differences. Their phonological inventories are quite similar except for the following segments: the palatalized phoneme /kj/ and the uvular /q/ from the dialect spoken in Rivadavia are realized as an affricate /tʃ/ and a velar /k/ in Ingeniero Juarez. Thus ‘mountain’ and ‘head’ in Rivadavia are ta k j enax and ɬete q while in Ingeniero Juárez, ta t ʃenax and ɬete k. There is also a morphological difference that the reader will notice in this article: in the dialect spoken in Rivadavia the 1st person possessive marker is a nasal, n- or nj-, while in Ingeniero Juárez it is a nasalized vowel: ũ- or ũj.

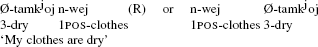

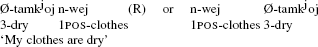

In monovalent clauses the verb can precede or follow the noun with no change in meaning, only a different emphasis on the first element of the clause:

-

(i)

-

(i)

In this paper we will refer either to murmuration or devoicing. In the literature on Wichi (Avram 2008; Terraza 2009; Nercesian 2011a, 2011b) the process triggered by /h/ on nasals is analyzed as “devoicing”. In Rivadavia dialect nasals are devoiced by /h/ (Terraza 2009) but in Ingeniero Juárez and Tartagal dialects we registered that /h/ triggers murmur phonation rather than devoicing. Spectrograms show that in murmured sounds there is a weakening of acoustic energy but voicing is maintained in nasals (for more details see Cayré Baito 2013).

See Terraza (2009: 26–27; 40–41) for arguments against the analysis of aspirated and devoiced nasals as a sequence of two segments.

The gloss neg3 stands for a negative morpheme which subsumes negation and person, in this case 3rd person. There are two ways of negating a clause in Wichi, with the suffix -hit’e or with a set of morphemes (a prefix and a suffix) subsuming person and negation: nam-a (1st), qa-a (2nd person), ni-a (3rd person). The second part of this negative morpheme, -a, has been analysed as the irrealis in Chorote (Carol 2014). In previous work (Terraza 2009) we analyzed this two affixes as a discontinuous morpheme.

It is worth mentioning that stress in Wichí requires a thorough study, since it does not always appear to be regular. We have noticed that some suffixes present a double behavior depending on the bases or stems with which they co-occur. In some cases they follow the general stress pattern (they attract stress) but in others they do not (Terraza 2009; Cayré Baito 2013):

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(i)

According to Terraza (2009) verbal derivation in Wichi is possible with two verbal roots semantically similar: wu and jen that have the meaning ‘to do’. Both roots require the verbalizer morpheme -a that is suffixed at the end of the derived verb. The same construction is analyzed as an instance of noun incorporation (see Nercesian, this volume). For more details and for the arguments against a noun incorporation analysis see Terraza (2009: 173–183).

This term is not used by Dixon and Aikhenvald (2002).

Here the diminutive suffix -xwax is reduced to -a. The derivation of the plural form of sinox ‘dog’ is as follows: /sinox-os/ (vowel copying and insertion), then the velar /x/ becomes /h/ in onset position yielding /sinohos/. The first vowel drops as a consequence of a syncope yielding /sinhos/ and finally /h/ devoices the nasal /n/ yielding [sin̥os].

The morpheme ha- is glossed here as an exclamatory marker. However, in its more common use it functions as an interrogative marker.

This is one of the words used for written word. It is formed on the verb root tson which means ‘drive, inject, poke’.

In the dialect of the first version the verb is -hemen (to like), and in the dialect used in the second version the same verb is -hemin.

Abbreviations

- 1:

-

= first person

- 2:

-

= second person

- 3:

-

= third person

- adv :

-

= adverb

- augm :

-

= augmentative

- appl :

-

= applicative

- caus :

-

= causative

- cl :

-

= classifier

- coll :

-

= collective

- dem :

-

= demonstrative

- dim :

-

= diminutive

- dir :

-

= directional

- distr :

-

= distributive

- excl :

-

= exclamatory marker

- foc :

-

= focus marker

- freq :

-

= frequentative

- fut :

-

= future

- incl :

-

= inclusive

- int :

-

= interrogative

- iter :

-

= iterative

- imp :

-

= imperfective

- loc :

-

= locative

- neg :

-

= negation

- nmlz :

-

= nominalizer

- obj :

-

= object

- pat :

-

= patientive

- pl :

-

= plural

- poss :

-

= possessive

- pro :

-

= pronoun

- profint:

-

= interrogative preform

- refl :

-

= reflexive marker

- sg :

-

= singular

- sub :

-

= subordinator

- tns :

-

= tense

- vblz :

-

= verbalizer

- ( ):

-

= deleted segments

- +:

-

= morpheme boundary

- σ :

-

= syllabic edge

References

Aikhenvald, A. (2002). Typological parameters for the study of clitics, with special reference to Tariana. In Word: a cross-linguistic typology (pp. 42–75). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Anderson, S. (2005). Aspects of the theory of clitics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Avram, M. L. Z. (2008). A phonological description of Wichí: The dialect of Misión La Paz, Salta, Argentina. Master’s Theses and Doctoral Dissertations, Paper 152. Available online in http://commons.emich.edu/theses/152/. Accessed 10 April 2011.

Buliubasich, C., Drayson, N., & de Bertea, S. M. (2004). Las palabras de la gente. Salta: CEPIHA.

Carol, J. (2014). LINCOM studies in Native American Linguistics: Vol. 72. Lengua chorote. Estudio fonológico y morfosintáctico. Munich: Lincom.

Cayré Baito, L. (2013). Fonología de la lengua Wichí (familia mataco-mataguaya). Una aproximación desde la perspectiva de la fonología generativa. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina.

Censabella, M. (1999). Las lenguas indígenas de Argentina: una mirada actual. Buenos Aires: Eudeba.

Claesson, A. (1994). A phonological outline of Mataco-Noctenes. International Journal of American Linguistics, 60(1), 1–38.

Dixon, R. M. W. & Aikhenvald, A. (Eds.) (2002). Word: a cross-linguistic typology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fernández Garay, A., & Spinelli, S. A. (2006). El sistema fonológico del wichí (familia mataco-mataguaya). In R. M. Ortiz Ciscomani (Ed.), Memorias: Tomo 2. Memorias del Octavo Encuentro Internacional de Lingüística en el Noroeste. Hermosillo: Universidad de Sonora.

Hunt, R. J. (1913). Collección Revista del Museo de La Plata: Vol. 22 El vejoz o aiyo. (pp. 7–214). Buenos Aires: La Plata.

Nercesian, V. (2011a). Stress in Wichí (Mataguayan) and its interaction with the word formation processes. Amerindia, 35, 75–102.

Nercesian, V. (2011b). Morfofonología. In Gramática del Wichí, una lengua chaqueña: Interacción fonología-morfología-sintaxis en el léxico. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Nercesian, V. (this volume) Wordhood and the interplay of linguistic levels in synthetic languages. An empirical study on Wichi (Mataguayan, Gran Chaco).

Terraza, J. (2002). Algunos aspectos del desplazamiento lingüístico en comunidades aborígenes Wichí. In A.F. Garay, & L. Golluscio (Eds.), Temas de Lingüística Aborigen II (pp. 245–262). Buenos Aires: Instituto de Lingüística, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Terraza, J. (2003). Los préstamos en Wichí y su aporte en el análisis fonético-fonológico. Paper presented at the 51th International Congress of Americanists, Santiago de Chile, 14–18 July.

Terraza, J. (2009). Gramática del Wichí: fonología y morfosintaxis. Ph.D. dissertation, Montreal: Université du Québec à Montréal.

Vidal, A., & Nercesian, V. (2009a). Loanwords in Wichí, a Mataco-Mataguayan language of Argentina. In M. Haspelmath & U. Tadmor (Eds.), Handbook of loanword typology (pp. 1015–1034). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Vidal, A., & Nercesian, V. (2009b). Wichí vocabulary (1187 entries). In M. Haspelmath & U. Tadmor (Eds.), World loanword database, Munich: Max Planck Digital Library.

Viñas Urquiza, M. T. (1974). Lengua mataca, Vol. 1. Buenos Aires: Centro de estudios lingüísticos, UBA. 2 T. Coll. “Archivo de lenguas precolombinas”.

Zidarich, M. (2004). Siete años más tarde. In Ministerio de Educación, Ciencia y Tecnología. Educación Intercultural Bilingüe en Argentina: sistematización de experiencias. Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Educación, Ciencia y Tecnología.

Zidarich, M., Calermo, T., Vallena, C., & Tomé, M. (1996). Tsalanawu. Libro de lectura para la Alfabetización Inicial en lengua Wichí. Buenos Aires: Secretaría de Desarrollo Social.

Zidarich, M., Calermo, T., & López, F. (2006). Auxiliares docentes de Sauzalito (Chaco). Tsalanawu. Libro de lectura para la Alfabetización Inicial (2nd ed.). Buenos Aires: Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Zwicky, A. M. (1977). On clitics. Indiana: Indiana University Linguistics Club.

Zwicky, A. M., & Pullum, G. K. (1983). Cliticization vs. inflection: English n’t. Language, 59(3), 502–513.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Terraza, J., Cayré Baito, L. Phonological, grammatical, and written words in Wichi. Morphology 24, 199–221 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-014-9240-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-014-9240-1