Abstract

By 2050, the Global South will contain three-quarters of the world’s urban inhabitants, yet no standardized categorizations of urban areas exist. This makes it challenging to compare sub-groups within cities. Sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) are a critical component of ensuring that populations are healthy and productive, yet SRHR outcomes within and across urban settings vary significantly. A scoping review of the literature (2010–2022) was conducted to describe the current body of evidence on SRHR in urban settings in the Global South, understand disparities, and highlight promising approaches to improving urban SRHR outcomes. A total of 115 studies were identified, most from Kenya (30 articles; 26%), Nigeria (15; 13%), and India (16; 14%), focusing on family planning (56; 49%) and HIV/STIs (43; 37%). Findings suggest significant variation in access to services, and challenges such as gender inequality, safety, and precarious circumstances in employment and housing. Many of the studies (n = 84; 80%) focus on individual-level risks and do not consider how neighborhood environments, concentrated poverty, and social exclusion shape behaviors and norms related to SRHR. Research gaps in uniformly categorizing urban areas and key aspects of the urban environment make it challenging to understand the heterogeneity of urban environments, populations, and SRHR outcomes and compare across studies. Findings from this review may inform the development of holistic programs and policies targeting structural barriers to SRHR in urban environments to ensure services are inclusive, equitably available and accessible, and direct future research to fill identified gaps.

Similar content being viewed by others

Elsie Akwara and Jessie Pinchoff contributed equally to this work.

Background

By 2030, over 60% of the world’s population will live in urban areas, with about 2.9 billion people living in cities where social, economic, and health inequalities have increased in recent decades [1]. This increase will largely take place in the Global South, driven both by natural population growth and rural–urban migration [2]. According to UN-HABITAT, there are currently an estimated 763 million internal migrants in the world [3]. While we refer to the Global South throughout this paper, we acknowledge the limitations of this terminology [4].

While some literature exists comparing sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) outcomes between urban and rural settings, generally urban populations are treated as a monolith. Cities offer major opportunities in resources and infrastructure to improve health outcomes, but these are not equitably distributed or available. The UNDESA World Social Report [1] highlights significant inequality within cities as urban areas are often segregated, with some neighborhoods or sub-groups experiencing worse health outcomes [1]. The heterogeneity, including the context and variegated spaces within urban areas, means that the unique needs of vulnerable urban populations, such as slum residents, street children, urban refugees, and migrants have to be targeted at the right delivery points. SRH risks for the urban poor include high rates of unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections, poor maternal and child health outcomes, and high rates of gender-based violence (GBV) [5]. Urban areas also have a higher prevalence of HIV particularly in sub-Saharan African cities, with heightened risk in urban slums [6,7,8,9].

Intersectionality, or the interconnected nature of social characterizations or identities including gender, race, and class, has rarely been explored as a framework for understanding drivers of urban SRHR outcomes, yet it is vital to a more holistic understanding of the ways in which social systems, power, and identity influence SRHR outcomes and behaviors. SRHR in urban contexts is critical to the development of healthy productive urban populations and, ultimately, the improvement of quality of life. Thus, addressing the challenges of urbanization, gender equity, and poverty within urban areas is key to achieving sustainable development [10]. Addressing SRHR is also a critical component of inclusive urbanization, an approach to proactively addressing inequities to ensure that no one is “left behind” or excluded from global health and economic gains and progress [11]. Without planning and attention, cities will continue to exclude certain residents, mainly migrants and the urban poor. This exclusion can be inadvertent, or in some situations intentional, and leads to a reinforcing cycle of poverty, exclusion, and deepening geographic segregation, often resulting in poor health outcomes, including for SRHR [12].

A major research challenge lies in defining the urban environment itself. There are no standard categories used to define cities or slums, and there is a lack of appropriate tools at national and city levels and limited capacities for data collection, management, and comparative analysis [13]. Research often refers to solely the rural vs urban dichotomy and fails to capture the heterogeneous nature of urban environments across countries and regions in terms of size/scale, topography, climate, services, and culture [10, 14]. Governments may define cities based on minimum population size, but this can vary from a minimum of 2500 people in Mexico to 20,000 in Nigeria, limiting comparability between countries [15]. Places are often labeled as urban or rural by government authorities. Once categorized, they are rarely recategorized, and the categorization used may be subject to political influence (e.g., redefining an area as urban may trigger different requirements regarding government allocation of resources or infrastructure) [16]. Differentiations within urban areas are even less clear. Some extant literature has categorized urban areas as slum and non-slum areas, but it is unclear how these categorizations are delineated. As the world urbanizes, understanding the full urban spectrum is critical to understanding and addressing how environment and infrastructure result in persistent heterogeneities in health, poverty, environmental risks, and other key livelihood and well-being factors that directly and indirectly relate to SRHR [17].

In addition to the lack of standard definitions, many surveys, such as the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS), that are often used to inform SRHR research, programs, and policies do not capture the diversity of experiences and needs of vulnerable groups within urban settings due to a lack of disaggregated data [13, 14, 17, 18]. Nationally representative surveys can only be disaggregated by urban vs rural, and the samples are not designed for intra-urban comparison. Satellite-derived datasets offer an opportunity to explore more objective measures of urbanicity, quantifying the degree of urbanization per grid cell (e.g., 1 km2 cells) as a combination of the built environment and population density that is independently derived from national administrative boundaries or input [19]. A gender lens is also critical as internal migration flows and urban populations have measurably “feminize” in recent decades, so girls and women now disproportionately account for the urban population in the Global South [20]. As adolescent girls and young women flock to cities for employment, prudent planning requires adopting a gendered and age-sensitive lens that will enable an understanding of the experiences and needs of adolescent girls [14, 21].

With this understanding, we conducted a scoping review with three objectives. First, to explore drivers, barriers, and contextual factors that relate to SRHR access and needs in urban contexts in the Global South. If studies disaggregate within urban areas, we report and explore these urbanicity measures and how they relate to SRHR outcomes. Second, the review describes the interventions tested to improve SRHR outcomes in urban areas, with a focus on studies that describe how the urban context relates to the design, implementation, or outcomes evaluated. Lastly, it outlines the next steps for priority research areas on SRHR in urban areas.

Methods

This scoping review focuses on SRHR in urban settings in the Global South using a list of countries defined by the UN [22] and the World Bank [16]. The Global South or low- and middle-income country (LMIC) are generally used to refer to countries in Latin America, Asia, Africa, and Oceania, with obvious limitations that warrant further examination. Given that there is no standardized definition of urban, we explore literature that defines its population as urban, using broad search terms that include metropolitan, peri-urban, slum, informal settlement, or inner city to capture any relevant settings. The literature search was conducted in PubMed/MEDLINE, SCOPUS, COCHRANE Library, Web of Science, POPLINE, JSTOR, and Google Scholar restricted to studies published between 2010 to 2022, according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The following keywords were used: “Urban,” “urbanization,” “city,” “slum,” “peri-urban,” “suburban,” “metropolitan,” “informal settlement,” “LMIC,” “Global South,” “sexual and reproductive health,” “SRH,” “SRHR,” “family planning,” “HIV,” “unmet need,” “fertility,” “pregnancy,” “contraception,” “abortion,” “gender-based violence,” “girl,” “women,” “female,” “adolescent,” “empower,” “empowerment,” “gender,” “equality,” “inequality,” “equity,” “disparity,” “poverty,” “economy,” “disparity,” “education,” “support,” “policy,” “SDG,” “inequality,” “UHC,” “Universal health coverage.”

In PubMed, MeSH terms were used to search the key words and used Booleans of “AND” and “OR.” In Web of Science, Topic (TS) was used to search the keywords using Booleans “AND” and “OR.” In Scopus, the Booleans “AND” and “OR” were used to search the keywords using title (TITLE), abstract (ABS), and keyword (KEY) (TITLE-ABS-KEY). We retained only studies published in English between 2010 and 2022. To identify relevant grey literature, a more targeted search of organizations that conduct urbanization and well-being research was conducted, including, Population Council, APHRC, UN-Habitat, and World Bank. Bibliographies in the identified literature (peer-reviewed and grey literature) were also searched manually to identify further, relevant references.

Data was extracted from relevant papers using predefined evidence summary templates. Information from each article was extracted to capture the following categories: “article title,” “authors,” “journal,” “year of publication,” “region,” “country,” “Urban definition (e.g., slums, general urban area, rural vs urban),” “Study population age,” “gender focus,” “study design,” “sample size,” “individual characteristics,” “attitudes and norms, interpersonal characteristics,” “neighborhood level,” “facility level,” societal/policy level,” and “main study objective summary,” “Dataset (e.g., if the study identified an accessible dataset for potential secondary analysis, such as DHS, MICS, IPUMS, PMA2020),” and “SRH area (e.g., FP, unintended pregnancy, abortion, HIV, fertility, early pregnancy, GBV).” One reviewer extracted each paper, and a second reviewer extracted a random sample of half of the articles, with a third reviewer if there was any disagreement. This is a scoping review that aims to present an overview of a very diverse body of research, including a range of study types, outcomes, and focus areas. To allow for a more inclusive review, a measure of quality is not reported.

The initial search yielded a total of 1550 studies identified through database searching and 160 additional pieces of grey literature, including targeted organizational searches and pulling references from other systematic reviews. The review began in 2021 but has been ongoing. After removing duplicates, 890 records were left for screening. Upon completion of title and abstract screening, 766 were excluded leaving 124 full texts deemed potentially relevant for review. Subsequently, 115 papers fulfilled our eligibility criteria (Table 1) and were included in this review (Fig. 1). After extracting the data into the evidence table, we summarized the results and mapped key findings. Results sections are categorized based on themes that emerged from the synthesis. We adopt a narrative synthesis approach given the variety of study designs, focus areas, outcomes, and the number of countries covered.

Results

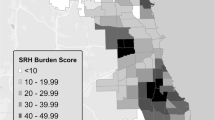

The 115 articles included in this review cover a range of topics and use a variety of methods. The two most common topics were family planning (FP) (56 articles, 49%), and HIV/STIs (43, 37%). Many articles focused on women of reproductive age (15–49 years) (44, 38%), with 18 focused on adolescents (10–19 years of age, 16% of articles), and another 18 focused on adolescents and young people (15–24 years, 16% of articles). Only 16 studies sampled men (14%), and another 11 interviewed providers or stakeholders (10%). Half of the articles (58, 50%) included were conducted in a general urban area, with only 26 (23%) focused on slums (Table 2). Most articles came from India, Kenya, or Nigeria (Fig. 2). Most were quantitative (87, 76%), with only 16 (14%) qualitative studies and 12 (10%) mixed methods. An additional 14 (12%) were randomized evaluations. We identified three other scoping reviews in this process, one focused specifically on urban family planning [17], one focused on adolescent SRHR challenges in urban slums [23], and one focused on the impact of interventions for urban family planning in slums in LMICs [12]. While focused on slightly different aspects of SRHR, overall, our findings are aligned with these reviews and identify related challenges and gaps.

Structural Environment

In urban environments, SRHR are shaped by structural factors including geographic and infrastructural challenges, concentrated poverty, and legal and policy environments affecting access to services and information, affordability, and physical safety [14, 18, 24]. Unlike in most rural areas, urban ones have a higher density of facilities offering SRH services and travel between communities is shorter, resulting in greater choices of health facilities and different patterns of accessing care [25]. Despite these shorter distances, transportation, pricing, and stigma still influence access to services. Slums are often located on the peri-urban fringe and therefore do not always have the same resources as the rest of a city due to social, economic, and political exclusion [14, 26]. Slum residents often face a choice between paying more for closer, lower-quality FP services or traveling outside their neighborhood to access low-cost, better-quality services [18, 27]. A South African study of mobile voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) found higher accessibility in urban areas with most users able to walk to the mobile site [28].

Urbanization may result in the concentration of poverty [1, 3], yet only 15 articles (13%) in the review capture the effects of poverty at the structural level on SRHR with most focusing more on individual behaviors and individual or household characteristics [6, 18, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Beyond individual income, urban slum environments function as “spatial poverty traps” in which multiple and reinforcing disadvantages are amplified at the neighborhood level, presenting unique challenges to SRHR, particularly among adolescents [14]. Growing up in resource-constrained settings, younger adolescent girls are at risk of early sexual initiation, unintended pregnancy, early marriage, HIV infection, and GBV [6, 36, 38, 41]. Studies also suggest a higher prevalence of HIV infection in slum communities and among the urban poor as well as heightened gender disparities in HIV that disproportionately affect urban adolescents and young people, particularly those with no education [6, 42,43,44,45]. Because poverty constrains the ability to access quality information and services, poverty reduction strategies need to be considered alongside SRH services [30]. A holistic approach to improving SRHR in urban areas is critical to address overlapping structural level barriers that may compound to exacerbate harms.

An additional set of seven articles (6%) captures how restrictive and exclusionary policies at local, sub-national, national, and global levels influence SRHR in urban environments. Because city governance structures often exclude urban slums from formal public services, in countries where most family planning clinics are in the public sector, people who live in slums tend to access informal clinics that offer services at higher costs [18]. Populations that are placed in marginalized positions from accessing safe and respectful SRHR services, such as female sex workers (FSWs), may face additional barriers imposed by inequitable policies [46, 47]. Urban areas have higher concentrations of FSWs, and this population experiences higher levels of unintended pregnancy than national estimates of all women, so restrictive abortion policies disproportionately create obstacles for FSWs in accessing safe abortion care. Local policing policies in Cameroon, for instance, were found to negatively influence condom usage and failure among FSWs [24]. On the national level, restrictive abortion policies create undue risk for all women and exacerbate harm for urban populations, such as FSWs. For example, countries where FSWs experience the greatest unintended pregnancies coincide with countries with the most restrictive abortion policies [24]. Relatedly, in the Philippines, FSWs with the least power to negotiate condom use were those that had been trafficked or faced higher poverty [47]. Even for young people in slums more generally, at the global scale, there is often a disconnect between legal human rights frameworks, notions of rights and entitlements, and the lived experiences of those living in urban slums in conditions of socioeconomic deprivation, as they are often not aware of their rights related to decisions to marry early, have children, terminate pregnancies, and engage in risky sexual behavior [37].

Gender Inequality

Gender inequality was discussed including inequitable gender norms at the community level and gender norms, behaviors, and power dynamics in interpersonal interactions related to social networks and partner dynamics. Only 11 articles (10%) consider the effect of gender inequality and inequitable gender norms on SRHR, with a focus on how such norms exacerbate GBV in urban settings. Exposure to violence in urban neighborhoods and slums includes personal experiences of sexual assault, harassment, and trafficking [14]. While the underlying causes of GBV are pervasive across geographic locations, certain risk factors that accompany urbanization processes, including urban poverty, low-quality sanitary facilities, fragmented social support networks, access to alcohol, and concentration of jobs associated with GBV such as factory and sex work, often lead to higher incidences of violence [14, 36]. The loosening of restrictive patriarchal norms that often accompanies urbanization resulting in improvements in women’s lives can also lead to women being less likely to tolerate GBV and equip them with resources and institutional support to better cope with violence [36]. Additionally, urbanization may increase women’s labor force participation rates, which may shift household gender dynamics and give women the economic resources to escape violent households. However, this dynamic also has the potential to result in backlashes of violence against women [36]. Given the relationship between gender norms, negotiation power, and violence, several articles emphasize the importance of equitable gender norms for violence prevention and SRHR, particularly for young people and migrants who are most vulnerable [36, 48,49,50,51].

Housing and Economic Insecurity

The influence of housing, economic insecurity, and social dynamics on safety considerations and behavioral norms were discussed [6, 30, 41, 52]. Weaker social cohesion in urban settings plays a role in establishing norms, communicating trust, and mobilizing collective resources [6]. Studies of diffusion of information in urban areas are useful; in urban areas information may be spread through personal contacts and less so at the community level [53]. Higher population density and lower social cohesion increase safety concerns, particularly for urban sub-populations that are already at risk for worse SRHR outcomes, such as adolescent girls, especially those who are solo migrants, and FSWs [14, 24, 47]. The physical environment, including housing density and cramped living conditions, increases exposure to early sexual activity, and violence, and may limit the use of contraceptives due to a lack of privacy [31]. Inadequate street lighting, the garbage that obstructs the vision of the streets, and the absence of clean and safe public toilets pose safety risks, especially to girls who perceive higher levels of community violence and lack of safety [14, 30, 32]. Girls living in urban areas report feeling unsafe walking around their communities at night and consider a greater proportion of spaces to be unsafe compared with girls living in rural environments [41, 52]. Housing deprivation, including overcrowding, poor quality of housing, lack of basic services such as water and electricity, and high levels of observed violence [32], also related to evictions [37], and the breakdown of social networks may all increase the vulnerability of young people to adverse SRHR outcomes, increasing their likelihood of engaging in risky sexual behaviors including transactional sex [35], increasing risk of adolescent pregnancy or STIs [32].

Health Facilities and Service Provision in Urban Settings

Issues related to health facilities and service provision in urban areas include unevenly distributed services, gaps in public sector service coverage, access to information/misinformation, confidentiality, cost, and product availability. Although SRH services are offered in both public and private health facilities, FP service delivery channels are often different in urban areas and gaps exist in service coverage from the public sector [26, 54]. Urban-dwelling women and adolescent girls generally prefer private over public facilities due to convenience and timeliness of services as well as more friendly environments and respectful providers, while other women may choose public facilities because they offer free service delivery [26, 27, 29, 55]. Drug shops and pharmacies play an important role in the provision of contraceptives, filling gaps in public sector service coverage in urban areas, particularly for vulnerable and harder-to-reach populations such as young and unmarried women (and men), as they may feel more comfortable at these sites [56]. With targeting, it is likely that contraceptive uptake can be increased—for example, in Bangladesh, a program based in slums successfully increased modern contraceptive use among married women of reproductive age (15–49 years) by 9 percentage points to reach 62%, higher than even non-slum areas (56%), reversing the intra-urban differential [26, 57].

Localized social networks in slums have been linked to the spread of misinformation about contraceptive methods and services that may create stigma for those seeking care and may dissuade young adults from utilizing SRH services [58]. In addition to social networks, nine studies focused on urban healthcare provision documenting how provider biases towards individuals seeking contraceptive and family planning information and services result in experiences of stigma, particularly among adolescents and FSWs [24, 29, 31, 59]. For HIV testing and treatment programs, one study in urban Zambia found a higher preference for home-based models because they reported harsh treatment by clinic workers and long wait times at facilities [57]. Most often at private facilities, providers may impose policies and procedures to restrict FP methods and impede clients’ access to FP based on age, parity, partner consent, and marital status [60,61,62,63]. The result is that people are discouraged from purchasing contraceptives from health centers or pharmacies, seeking SRH care, and undermining their agency as it relates to contraceptive choices [24, 59].

Evidence on Tested Interventions and Programs

Overall, only 21 evaluation studies (18%) on tested interventions in urban settings were identified, However [14], many approaches failed to explore or to take advantage of the urban environment and infrastructure and to tailor programs. Within the studies that did emerge, there is mixed evidence on programs and interventions to improve SRHR outcomes among urban populations. In order to address the complex and interrelated factors that contribute to SRHR at the social and community levels, programs must take into account socio-cultural contexts and consider the relationship between the health of urban individuals and the environments they live in [30, 40, 51].

There is promise in multi-sectoral community-based interventions designed for adolescents, including those that utilize mentor-delivered curricula through safe spaces, to facilitate access to information, services, and social ties to improve SRHR outcomes, particularly for marginalized girls [38, 41, 64, 65]. These approaches have successfully improved SRHR outcomes related to delaying childbearing, reducing aspects of GBV attitudes and beliefs, increasing access to and decision-making about contraceptive and FP services, increasing voluntary counseling and testing for HIV, and increasing social participation and social safety networks. Relatedly, gender-transformative approaches focused on challenging and modifying harmful masculine norms and power dynamics may increase protective sexual behaviors, reduce violence, reduce transmission of HIV/STIs, and improve equitable gender relations [49, 66, 67]. Gaining the support of family members and engaging community members and stakeholders that are often gatekeepers to young peoples’ well-being (e.g., religious leaders, community leaders, parents, teachers, and peers) holds promise for GBV prevention and family planning service provision in urban settings [41, 50, 68].

Some programs leveraged behavior change approaches and a range of communication strategies. One evaluation adopted a peer-led interpersonal communication (IPC) approach to increase awareness and uptake of a new inner condom and found that this was a useful strategy to change norms and perceptions to increase acceptability and uptake [69]. Another program found text reminders to be effective in encouraging contraceptive uptake and clinic visits; however, effects were concentrated among women under 25 who may be more digitally engaged [70] though another found no effect of interactive text messages on patient retention for HIV care in Kenya [71]. The SASA! Project in South Africa used videos, performances, and other communication methods to address GBV [53]. Several studies tested financial incentives as nudges to change behaviors around HIV testing and male circumcision [72,73,74,75,76].

Several evaluations of facility-level intervention strategies to improve the quality of FP services and FP uptake among poor women in urban areas were reviewed [77,78,79]. The Urban Reproductive Health Initiative (URHI) program was initiated to increase contraceptive use in urban areas in four countries: India (Uttar Pradesh), Kenya, Nigeria, and Senegal through a range of country-specific demand and supply-side interventions [39, 80]. Evidence from the URHI in Nigeria and Kenya shows how targeting efforts to the urban poor and the particular barriers they face can successfully generate demand, improve efficiency in the delivery of FP services, and increase uptake of FP [54, 81, 82]. Results overall and across outcomes emphasize the need for larger system changes and more comprehensive strategies to address community-level factors, such as structural poverty or persistent gender norms, in order to achieve program sustainability and long-term impact [23, 78].

The most common outcome for rigorous evaluation was HIV testing and treatment in urban settings, comparing control arms to treatment groups that included financial incentives, different messaging, or different delivery of HIV services. Fourteen (12%) articles were randomized controlled trials testing these interventions. However, almost none considered aspects of the urban environment in their analysis. While five of the 14 compared urban to rural settings, this was the extent of the comparison. One interesting approach was a paper written to complement the PopART Evaluation on HIV prevention in South Africa and Zambia, in which researchers assessed the different communities to understand how the community dynamics could influence the observed outcomes [83].

Discussion

This scoping review describes the current body of literature on SRHR in urban settings in the Global South published between 2010 and 2022. Most of the 115 studies identified were conducted in SSA and focused mainly on women of reproductive age (15–49 years), with less attention to the specific needs of young adolescent and marginalized girls as well as other sub-groups. Almost a third (37 articles; 32%) engaged men, mostly when focused on HIV as an outcome. Included publications focused heavily on FP and HIV/STIs, with few examining other aspects of SRHR such as abortion or menstrual health. Most of the studies were cross-sectional and quantitative in nature, with 14 rigorously designed randomized evaluations specifically exploring HIV outcomes. To address the complex and interrelated factors that contribute to SRHR at the social and community levels, programs must take into account socio-cultural contexts and consider the relationship between the health of urban individuals and the environments they are embedded in. Often, the focus is on individual-level correlates, failing to consider this important contextual information [30, 40, 51]. Similarly, there were few studies that focused on intra-urban differences, highlighting the need for urban surveys and datasets that allow for comparisons within cities, and with a sufficient sampling of marginalized groups.

While all papers included in the review focus on urban populations, few unpack how the urban environment and context specifically influence or relate to SRHR-related behaviors, preferences, and service provision. Research often focuses on large cities or broad urban–rural comparisons and may overlook the changes happening in smaller settlements and urban peripheries [17].

There is no standard definition of “urban” or “slums,” limiting the ability to compare key findings across studies. This results in entire groups of people and places not being counted and important aspects of city conditions, intra-urban differences, and experiences not being measured due to a lack of evidence-based planning and programming [13, 26]. Overall, urban residents tend to have better SRHR outcomes [84], but studies with intra-urban comparisons find that slum residents and the urban poor tend to fare worse (Table 3). Clearly, a more granular understanding of how social forces such as urban poverty, inequality, and social norms including gender norms intersect and are distributed across urban neighborhoods is necessary. In recent years, stakeholders’ interest in research in urban areas has increased but more research is still needed to understand the dynamics within and across city neighborhoods and how urban environments and community characteristics may contribute to SRHR outcomes. Precise measurement of these factors will enable a deeper understanding of SRHR risks, opportunities, and behaviors in urban environments and emerging technology such as satellite imagery may hold promise for improving data collection and analysis with real-time monitoring capabilities [19].

Overall, we found few evaluations of interventions or policies focused on SRHR in urban areas in the Global South. However, this is an area of increasing interest and publication encouraging shifts towards a holistic approach that addresses socio-environmental and economic conditions that heighten vulnerability to poor SRHR outcomes in the urban context. HIV prevention is perhaps the most rigorously studied outcome, with 14 randomized evaluations in urban areas included in this review; however, few if any provided additional details regarding their urban sample. Furthermore, given the advent of COVID-19 and the disruption of services, there is a need to explore how to effectively scale up mHealth interventions to reach the urban poor but not miss key populations given challenges such as the digital gender divide [85]. Evaluations may take a long time and not allow for real-time flexibility; mixed methods approaches may be useful as programs evolve and adapt to dynamic circumstances.

Limitations

This review acknowledges certain limitations, including restrictions around language (English only), our search of two databases, and inclusion after the 2010 date may have missed some important publications. Although included in the search, our results highlight the need for future studies to explore high-risk and marginalized sub-groups, such as LGBTQ youth and their specific SRHR needs and challenges in urban settings. Due to the mix of study designs and other factors, this review did not apply an appraisal of rigor to individual studies. An additional limitation of this review is related to the search terms used to identify relevant publications. This review only captures studies that explicitly reference their focus on urban contexts. Because some studies may have instead used place names or other terms, this review may not have captured all relevant articles. Despite these limitations, the strengths of this review include our broad narrative synthesis/scoping review approach and the inclusion of many different components of SRHR outcomes.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Aspects of the urban environment offer major opportunities to improve SRHR, but these are not equitably distributed or available. While urban areas often have more infrastructure and services than rural areas, geographic proximity to such resources does not guarantee access to them, particularly for poor and marginalized young people [50]. Additionally, social development in urban areas, including infrastructure (roads, housing, sanitation) and investments in health and education, have not kept pace with urban population growth, particularly in many sub-Saharan African countries [18]. Existing surveys and data are insufficient to capture within-city heterogeneity in SRHR needs and experiences. While geospatial approaches may be useful to categorize urban environments and identify hotspots of poor health outcomes, these do not capture larger normative, political, and regulatory barriers to change [20, 86, 87]. As most of the world’s population will urbanize in the coming decades, proactive strategies and interventions tailored to the urban environment and the distinct needs and experiences of urban populations are critical in creating enabling environments for accessing SRH services and improving SRHR outcomes. Without a rights-based, inclusive, and evidence-based approach, urban areas may see widening disparities, particularly among marginalized populations. Better measurement and disaggregation of urban populations and environments, through targeted surveys and innovative strategies such as machine learning of social media and phone data are useful to understand needs, experiences, and health equity differentials among urban groups. Finally, developing and evaluating programs that address structural barriers to SRHR in urban environments, including public safety, poverty, transportation costs, and gender inequality through a more holistic approach may be more effective at improving SRHR outcomes.

References

UNDESA. Inequality in a rapidly changing world. UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2020. Available from: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3847753. Accessed 14 Sept 2022.

Revia A, Satterthwaite D, Aragón-Durand F, Corfee-Morlot J, Kiunsi R, Peling M, et al. Urban areas. In: Climate change 2014 – impact, adaptation, and vulnerability: Global and sectoral aspects: Cambridge University Press; 2014. p. 535–612.

UN-HABITAT. World cities report 2020. UN-Habitat. 2020. Available from: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3905819. Accessed 11 Aug 2022.

Khan T, Abimbola S, Kyobutungi C, Pai M. How we classify countries and people—and why it matters. BMJ Glob Health BMJ Specialist J. 2022;7:e009704.

Mberu B, Mumah J, Kabiru C, Brinton J. Bringing sexual and reproductive health in the urban contexts to the forefront of the development agenda: the case for prioritizing the urban poor. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18:1572–7.

Magadi MA. The disproportionate high risk of HIV infection among the urban poor in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:1645–54.

Madise NJ, Ziraba AK, Inungu J, Khamadi SA, Ezeh A, Zulu EM, et al. Are slum dwellers at heightened risk of HIV infection than other urban residents? Evidence from population-based HIV prevalence surveys in Kenya. Health Place. 2012;18(5):1144–52.

Hayes R, Floyd S, Schaap A, Shanaube K, Bock P, Sabapathy K, et al. A universal testing and treatment intervention to improve HIV control: one-year results from intervention communities in Zambia in the HPTN 071 (PopART) cluster-randomised trial. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002292.

Plymoth M, Sanders EJ, Elst EMVD, Medstrand P, Tesfaye F, Winqvist N, et al. Socio-economic condition and lack of virological suppression among adults and adolescents receiving antiretroviral therapy in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0244066.

Liddle B. Urbanization and inequality/poverty. Urban Sci. 2017;1:35.

McGranahan G, Schensul D, Singh G. Inclusive urbanization: can the 2030 Agenda be delivered without it? Environ Urban SAGE Publications Ltd. 2016;28:13–34.

Wado YD, Bangha M, Kabiru CW, Feyissa GT. Nature of, and responses to key sexual and reproductive health challenges for adolescents in urban slums in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. Reprod Health. 2020;17:149.

UN-HABITAT. World cities report 2022: Envisaging the future of cities | UN-Habitat. UN-Habitat. 2022. Available from: https://unhabitat.org/world-cities-report-2022-envisaging-the-future-of-cities. Accessed 14 Sept 2022.

Chant S, Klett-Davies M, Ramalho J. Challenges and potential solutions for adolescent girls in urban settings: a rapid evidence review. London: Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence; 2017. Available from: https://www.gage.odi.org/publication/challenges-solutions-urban-settings-rapid-evidence-review/. Accessed 14 Sept 2022

International Labour Organization. Inventory of official national-level statistical definitions for rural/urban areas. Geneva, Switzerland. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/%2D%2D-dgreports/%2D%2D-stat/documents/genericdocument/wcms_389373.pdf. Accessed 14 Sept 2022.

Dijkstra L, Hamilton E, Lall S, Wahba S. How do we define cities, towns, and rural areas?. World Bank. 2020. Available from: https://blogs.worldbank.org/sustainablecities/how-do-we-define-cities-towns-and-rural-areas. Accessed 12 Aug 2022.

Duminy J, Cleland J, Harpham T, Montgomery MR, Parnell S, Speizer IS. Urban family planning in low- and middle-income countries: a critical scoping review. Front Glob Womens Health. 2021;2:749636.

Ezeh AC, Kodzi I, Emina J. Reaching the urban poor with family planning services. Stud Fam Plann. 2010;41:109–16.

Adlakha D. Quantifying the modern city: emerging technologies and big data for active living research. Front Public Health. 2017;5. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00105. Accessed 15 Aug 2022.

Neal S, Ruktanonchai C, Chandra-Mouli V, Matthews Z, Tatem A. Mapping adolescent first births within three east African countries using data from demographic and health surveys: exploring geospatial methods to inform policy. Reprod Health. 2016;13:98.

Brady M. Chapter 7—safe spaces for adolescent girls. In: Adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health: charting directions for a second generation of programming— background document for the meeting. New York: UNFPA. 2003 [cited 2022 Aug 15]. Available from: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-pgy/1496/.

Global South Countries (Group of 77 and China) - Partnership program - the finance center for south-south cooperation. Available from: http://www.fc-ssc.org/en/partnership_program/south_south_countries. Accessed 26 Feb 2023.

Ganle JK, Baatiema L, Ayamah P, Ofori CAE, Ameyaw EK, Seidu A-A, et al. Family planning for urban slums in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review of interventions/service delivery models and their impact. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20:186.

Bowring AL, Schwartz S, Lyons C, Rao A, Olawore O, Njindam IM, et al. Unmet need for family planning and experience of unintended pregnancy among female sex workers in urban Cameroon: results from a national cross-sectional study. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2020;8:82–99.

Levy JK, Curtis S, Zimmer C, Speizer IS. Assessing gaps and poverty-related inequalities in the public and private sector family planning supply environment of urban Nigeria. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2014;91:186–210.

Angeles G, Ahsan KZ, Streatfield PK, El Arifeen S, Jamil K. Reducing inequity in urban health: have the intra-urban differentials in reproductive health service utilization and child nutritional outcome narrowed in Bangladesh? J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2019;96:193–207.

Escamilla V, Calhoun L, Winston J, Speizer IS. The role of distance and quality on facility selection for maternal and child health services in urban Kenya. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2018;95:1–12.

van Rooyen H, McGrath N, Chirowodza A, Joseph P, Fiamma A, Gray G, et al. Mobile VCT: reaching men and young people in urban and rural South African pilot studies (NIMH Project Accept, HPTN 043). AIDS Behav. 2013;17:2946–53.

Adedze M, Osei-Yeboah R, Morhe E, Vitalis N. Exploring sexual and reproductive health needs and associated barriers of homeless young adults in urban Ghana: a qualitative study. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2022;19:1006–9.

Beguy D, Mumah J, Wawire S, Muindi K, Gottschalk L, Kabiru C. Status report on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents living in urban slums in Kenya. Population Council. 2013. Available from: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-rh/284. Accessed 15 Aug 2022.

Beguy D, Mumah J, Gottschalk L. Unintended pregnancies among young women living in urban slums: evidence from a prospective study in Nairobi City, Kenya. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101034.

Brahmbhatt H, Kågesten A, Emerson M, Decker MR, Olumide AO, Ojengbede O, et al. Prevalence and determinants of adolescent pregnancy in urban disadvantaged settings across five cities. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med. 2014;55:S48–57.

Dinsa G, Buli E, Hurlburt S, Gebreyohannes Y, Arsenault C, Yakob B, et al. Equitable distribution of poor quality of care? Equity in quality of reproductive health services in Ethiopia. Health Syst Reform. 2022;8(1):e2062808.

Greif MJ, Dodoo FN-A, Jayaraman A. Urbanisation, poverty and sexual behaviour: the tale of five African cities. Urban Stud Edinb Scotl. 2011;48:947–57.

Kamndaya M, Vearey J, Thomas L, Kabiru CW, Kazembe LN. The role of material deprivation and consumerism in the decisions to engage in transactional sex among young people in the urban slums of Blantyre. Malawi Glob Public Health. 2016;11:295–308.

McIlwaine C. Urbanization and gender-based violence: exploring the paradoxes in the global South. Environ Urban SAGE Publications Ltd. 2013;25:65–79.

Rashid SF. Human rights and reproductive health: political realities and pragmatic choices for married adolescent women living in urban slums, Bangladesh. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2011;11:S3.

Renzaho AMN, Kamara JK, Doh D, Bukuluki P, Mahumud RA, Galukande M. Do Community-based livelihood interventions affect sexual and reproductive health and rights of young people in slum areas of Uganda: a difference-in-difference with kernel propensity score matching analysis. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2022;99:164–89.

Speizer IS, Fotso JC, Davis JT, Saad A, Otai J. Timing and circumstances of first sex among female and male youth from select urban areas of Nigeria, Kenya, and Senegal. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med. 2013;53:609–16.

Weeks JR, Getis A, Stow DA, Hill AG, Rain D, Engstrom R, et al. Connecting the dots between health, poverty and place in Accra, Ghana. Ann Assoc Am Geogr Assoc Am Geogr. 2012;102:932–41.

Austrian K, Muthengi E, Riley T, Mumah J, Kabiru C, Abuya B. Adolescent girls initiative - Kenya Baseline Report [Internet]. Population Council. Nairobi, Kenya; 2015. Available from: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-pgy/638/. Accessed 15 Aug 2022.

Lulseged S, Melaku Z, Habteselassie A, West CA, Gelibo T, Belete W, et al. Progress towards controlling the HIV epidemic in urban Ethiopia: findings from the 2017–2018 Ethiopia population-based HIV impact assessment survey. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0264441.

Nada KH, Suliman EDA. Violence, abuse, alcohol and drug use, and sexual behaviors in street children of Greater Cairo and Alexandria. Egypt AIDS Lond Engl. 2010;24(Suppl 2):S39–44.

Kennedy SB, Atwood KA, Harris AO, Taylor CH, Gobeh ME, Quaqua M, et al. HIV/STD risk behaviors among in-school adolescents in post-conflict Liberia. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2012;23:350–60.

Bergam S, Sibaya T, Ndlela N, Kuzwayo M, Fomo M, Goldstein MH, et al. “I am not shy anymore”: a qualitative study of the role of an interactive mHealth intervention on sexual health knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of South African adolescents with perinatal HIV. Reprod Health. 2022;19:217.

Kohler PK, Campos PE, Garcia PJ, Carcamo CP, Buendia C, Hughes JP, et al. Sexually transmitted infection screening uptake and knowledge of sexually transmitted infection symptoms among female sex workers participating in a community randomised trial in Peru. Int J STD AIDS. 2016;27:402–10.

Urada LA, Morisky DE, Pimentel-Simbulan N, Silverman JG, Strathdee SA. Condom negotiations among female sex workers in the Philippines: environmental influences. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33282.

Agyekum MW, Henry EG, Kushitor MK, Obeng-Dwamena AD, Agula C, OpokuAsuming P, et al. Partner support and women’s contraceptive use: insight from urban poor communities in Accra. Ghana BMC Womens Health. 2022;22:256.

Das M, Verma R, Ghosh S, Ciaravino S, Jones K, O’Connor B, et al. Community mentors as coaches: transforming gender norms through cricket among adolescent males in urban India. Gend Dev. 2015;23:61–75.

HC3. Influencing the sexual and reproductive health of urban youth through social and behavior change communication: a literature review [Internet]. In: The Health Communication Capacity Collaborative (HC3). 2014. Available from: https://www.comminit.com/content/influencing-sexual-and-reproductive-health-urban-youth-through-social-and-behaviorchang. Accessed 15 Aug 2022.

Renzaho AMN, Kamara JK, Georgeou N, Kamanga G. Sexual, reproductive health needs, and rights of young people in slum areas of Kampala, Uganda: a cross sectional study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0169721.

Abuya BA, Onsomu EO, Moore D. Determinants of educational exclusion: poor urban girls’ experiences in- and out-of school in Kenya. Prospects. 2014;44:381–94.

Starmann E, Heise L, Kyegombe N, Devries K, Abramsky T, Michau L, et al. Examining diffusion to understand the how of SASA!, a violence against women and HIV prevention intervention in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:616.

Chin-Quee DS, Abrejo F, Chen M, Lashari T, Olsen P, Habib Z, et al. Task sharing of injectable contraception services in pakistan: a randomized controlled trial. Stud Fam Plann. 2021;52:23–39.

Keesara SR, Juma PA, Harper CC. Why do women choose private over public facilities for family planning services? A qualitative study of post-partum women in an informal urban settlement in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:335.

Corroon M, Kebede E, Spektor G, Speizer I. Key role of drug shops and pharmacies for family planning in Urban Nigeria and Kenya. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2016;4:594–609.

Limbada M, Bwalya C, Macleod D, Shibwela O, Floyd S, Nzara D, et al. Acceptability and preferences of two different community models of ART delivery in a high prevalence urban setting in Zambia: cluster-Randomized Trial, Nested in the HPTN 071 (PopART) Study. AIDS Behav. 2022;26:328–38.

Beguy D, Ezeh A, Mberu B, Emina J. Changes in use of family planning among the urban poor: evidence from Nairobi slums. Popul Dev Rev. 2017;43:216–34.

MbaduMuanda F, Gahungu NP, Wood F, Bertrand JT. Attitudes toward sexual and reproductive health among adolescents and young people in urban and rural DR Congo. Reprod Health. 2018;15:74.

Calhoun LM, Speizer IS, Rimal R, Sripad P, Chatterjee N, Achyut P, et al. Provider imposed restrictions to clients’ access to family planning in urban Uttar Pradesh, India: a mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:532.

Hebert LE, Schwandt HM, Boulay M, Skinner J. Family planning providers’ perspectives on family planning service delivery in Ibadan and Kaduna, Nigeria: a qualitative study. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2013;39:29–35.

Schwandt HM, Speizer IS, Corroon M. Contraceptive service provider imposed restrictions to contraceptive access in urban Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:268.

Tumlinson K, Okigbo CC, Speizer IS. Provider barriers to family planning access in urban Kenya. Contraception. 2015;92:143–51.

Austrian K, Soler-Hampejsek E, Mumah J, Kangwana B, Dibaba Wado Y, Abuya B, et al. Adolescent girls initiative–Kenya: midline results report. Population Council. 2018. Available from: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-pgy/997. Accessed 15 Aug 2022.

Erulkar A, Gebru H, Mekonnen G. Biruh Tesfa ('Bright Future’) program provides domestic workers, orphans and migrants in urban Ethiopia with social support, HIV education and skills [Internet]. Population Council. 2011. Available from: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-pgy/96. Accessed 15 Aug 2022.

Hidrobo M, Peterman A, Heise L. The effect of cash, vouchers, and food transfers on intimate partner violence: evidence from a randomized experiment in northern Ecuador †. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2016;8:284–303.

Psaki SR, Pulerwitz J, Zieman B, Hewett PC, Beksinska M. What are we learning about HIV testing in informal settlements in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa? Results from a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0257033.

Huda F, Chowdhuri S, Sarker B, Islam N, Ahmed A. Prevalence of unintended pregnancy and needs for family planning among married adolescent girls living in urban slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh [Internet]. Population Council. 2013. Available from: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-rh/266/. Accessed 15 Aug 2022.

Pinchoff J, Boyer CB, Nag Chowdhuri R, Smith G, Chintu N, Ngo TD. The evaluation of the woman’s condom marketing approach: what value did peer-led interpersonal communication add to the promotion of a new female condom in urban Lusaka? PLoS One. 2019;14:e0225832.

Leight J, Hensly C, Chissano M, Safran E, Ali L, Dustan D, et al. The effects of text reminders on the use of family planning services: evidence from a randomised controlled trial in urban Mozambique. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7:e007862.

van der Kop ML, Muhula S, Nagide PI, Thabane L, Gelmon L, Awiti PO, et al. Effect of an interactive text-messaging service on patient retention during the first year of HIV care in Kenya (WelTel Retain): an open-label, randomised parallel-group study. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3:e143–52.

Thornton R, Godlonton S. Medical male circumcision: how does price affect the risk-profile of take-up? Prev Med. 2016;92:68–73.

Choko AT, Corbett EL, Stallard N, Maheswaran H, Lepine A, Johnson CC, et al. HIV self-testing alone or with additional interventions, including financial incentives, and linkage to care or prevention among male partners of antenatal care clinic attendees in Malawi: an adaptive multi-arm, multi-stage cluster randomised trial. PLoS Med. 2019;16:e1002719.

Chamie G, Kwarisiima D, Ndyabakira A, Marson K, Camlin CS, Havlir DV, et al. Financial incentives and deposit contracts to promote HIV retesting in Uganda: a randomized trial. PLoS Med. 2021;18:e1003630.

Chang W, Matambanadzo P, Takaruza A, Hatzold K, Cowan FM, Sibanda E, et al. Effect of prices, distribution strategies, and marketing on demand for HIV self-testing in Zimbabwe. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e199818.

Kuringe E, Christensen A, Materu J, Drake M, Majani E, Casalini C, et al. Effectiveness of cash transfer delivered along with combination HIV prevention interventions in reducing the risky sexual behavior of adolescent girls and young women in Tanzania:Cluster randomized controlled trial. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022;8:e30372.

Atagame K, Benson A, Calhoon L, Corroon M, Guilkey D, Lyiwose P, et al. Evaluation of the Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative (NURHI) Program. Stud Fam Plann. 2017;48:253–68.

Babalola S, Kusemiju B, Calhoun L, Corroon M, Ajao B. Factors associated with contraceptive ideation among urban men in Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet Off Organ Int Fed Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;130(Suppl 3):E42–6.

Speizer IS, Calhoun LM, McGuire C, Lance PM, Heller C, Guilkey DK. Assessing the sustainability of the Nigerian urban reproductive health initiative facility-level programming: longitudinal analysis of service quality. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:559.

Winston J, Calhoun LM, Corroon M, Guilkey D, Speizer I. Impact of the urban reproductive health initiative on family planning uptake at facilities in Kenya, Nigeria, and Senegal. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18:9.

Benson A, Calhoun LM, Corroon M, Lance P, O’Hara R, Otsola J, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of the Tupange urban family planning program in Kenya. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2017;43:75–87.

Krenn S, Cobb L, Babalola S, Odeku M, Kusemiju B. Using behavior change communication to lead a comprehensive family planning program: the Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2014;2:427–43.

Bond V, Chiti B, Hoddinott G, Reynolds L, Schaap A, Simuyaba M, et al. “The difference that makes a difference”: highlighting the role of variable contexts within an HIV Prevention Community Randomised Trial (HPTN 071/PopART) in 21 study communities in Zambia and South Africa. AIDS Care. 2016;28(Suppl 3):99–107.

Ochako R, Askew I, Okal J, Oucho J, Temmerman M. Modern contraceptive use among migrant and non-migrant women in Kenya. Reprod Health. 2016;13:67.

Ahmed SAKS, Ajisola M, Azeem K, Bakibinga P, Chen Y-F, Choudhury NN, et al. Impact of the societal response to COVID-19 on access to healthcare for non-COVID-19 health issues in slum communities of Bangladesh, Kenya, Nigeria and Pakistan: results of pre-COVID and COVID-19 lockdown stakeholder engagements. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e003042.

Kent JL, Harris P, Thompson S. What gets measured does not always get done. Lancet Glob Health Elsevier. 2022;10:e1235.

World Bank Group. Global responses to COVID-19 in slums and cities: practices from around the world. Washington DC: World Bank Group; 2020.

Acknowledgements

This analysis was conducted with support from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation (Grant #2020-1416).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Akwara, E., Pinchoff, J., Abularrage, T. et al. The Urban Environment and Disparities in Sexual and Reproductive Health Outcomes in the Global South: a Scoping Review. J Urban Health 100, 525–561 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-023-00724-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-023-00724-z