Abstract

Global initiatives have raised awareness of the need for cross-departmental and cross-sectoral activities to support urban health, sustainability, and equity, with respective indicators routinely used as a way to catalyze and monitor action toward pre-defined goals. Despite the existence of at least 145 urban health indicator (UHI) tools globally, there has been very little research on the use of indicators by policy- and decision-makers; more attention has been devoted to their development and validation. This paper describes the second part of a two-part systematic review of the characteristics (part A) and use (part B, this part) of UHI tools by municipal built environment policy- and decision-makers. Part B is a narrative synthesis of studies on the use of UHI tools. This PRISMA-P compliant review follows a mixed methods sequential explanatory design. The search was conducted using seven bibliographic databases, grey literature searches, and key journal hand searches. Ten studies describing the use of ten UHI tools in seven countries were included in the narrative synthesis, resulting in development of a theory of change (ToC). We found that both expert-led and participatory indicator projects can be underpinned by research evidence and residents’ knowledge. Our findings contradict the dominant view of indicator use in policy-making as a linear process, highlighting a number of technical, organizational, political, knowledge, and contextual factors that affect their use. Participatory UHI tools with community involvement were generally more effective at supporting “health in all policies” and “whole-of-society” approaches to governing healthy cities than expert-led processes. UHI tool producers proposed a range of techniques to address urban health complexity characteristics. Finally, in combining data from both parts of the review, we found that potentially important UHI tool features, such as neighbourhood-scale data, were influential in the use of indicators by built environment policy- and decision-makers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Global initiatives including the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the World Health Organization’s Healthy Cities Network have raised awareness of the need for cross-departmental and cross-sectoral activities to support urban health, sustainability, and equity [1, 2]. The establishment and use of relevant indicators, and in particular of urban health indicator (UHI) tools, is one route through which such initiatives seek to catalyze and monitor action toward these goals [3,4,5, 7]. We define UHI tools as “collection [s] of summary measures about the physical urban environment’s contribution to human health and wellbeing,” with a broad interpretation of health that expands to “related concepts of quality of life, liveability and wellbeing” [9]. Our previous study (called part A of this review) provides a global census and analysis of UHI tools and their characteristics (described below) [10]. We confirmed that attention has been devoted primarily to indicator development and validation, and there has been very little research on the use of such indicators by policy- and decision-makers [10,11,12,13, 15, 18].

Part A of our review extracted and analyzed data about the characteristics of 145 UHI tools, comprising 8006 indicators. We developed a taxonomy, classifying UHI tools by topic, spatial scale, format, scope, and purpose. UHI tools were produced in 28 countries, and a further 28 tools could be applied internationally. Our review supported the argument that neighbourhood-scale data are increasingly available and displayed on interactive maps, suggesting that such tools would be useful for urban planners, particularly to identify spatial and health inequalities [10, 19, 20]. We found a degree of similarity in the domains measured across UHI tool topics particularly among health and well-being, quality of life, and liveability. The majority of UHI tools in the review (82.8%, 120/145) intended to inform policy- and decision-making and were based on evidence (e.g., peer-reviewed studies underpinned 52.4% (76/145) of UHI tools).

UHI tools are often proposed for use by policy-makers assuming that a rational evidence-based policy model is in place, yet knowledge translation and policy scholars critique this model and the potential for indicators to be used in policy-making [12, 13, 18, 21, 22]. Innes and Booher claimed that most indicator reports fail to inform policy because their producers “relied on a simplistic model of how information drives policy” [12]. While Webster and Sanderson described WHO Healthy City Indicators as part of a logical “evidence-based, rational policy making and priority setting” process [23]. Given these diverse views, indicators have been variously conceptualized as rational technical tools in a linear policy process or as social constructs defined by local negotiation and context [11, 13, 15].

There are also diverse views about how indicators support policy- and decision-makers with the complexity of urban health. Complex systems are characterized as interconnected, dynamic, non-linear, adaptive, and governed by feedback, among other features [24,20,26]. The impact of urban environments on health has been described as an emergent property of a complex system composed of multiple subsystems such as housing, transport, and air quality [27,23,29]. Components of the built environment interact with social and economic factors, creating health equity challenges and adding further complexity [30]. This complexity hinders the study of urban environment exposures and effects, the production of validated indicators, and the creation of appropriate policy responses [5, 11, 28, 31, 32]. The first part of this review (part A) demonstrated that UHI tool producers are aware of these complexity challenges, yet few described the role of indicators in strategies to address them [10].

Notwithstanding the technical improvements to UHI tools identified in part A, there is a lack of research on whether they have succeeded in informing built environment policy- and decision-makers or attempted to support them with the complexity of urban health. To address this gap, this paper describes the second part (part B) of a two-part systematic review of the characteristics and use of urban health indicator (UHI) tools by municipal built environment policy- and decision-makers. Our narrative synthesis analyzes studies on the use and perceptions of these tools. Given the potential importance of the process of indicator development, as highlighted by Innes and Booher, we investigate the circumstances and actors involved in creating UHI tools and the impact of such processes [12].

Methods

The review methods are outlined in the PRISMA-P compliant protocol with additional information in the part A results, both published previously [9, 10]. The review follows a mixed methods sequential explanatory design [33]. We combined quantitative data about the characteristics of UHI tools (part A) with qualitative data about their use (part B). The search strategy and review of papers were conducted simultaneously for both parts of our broader study; however, the review methods diverged with regard to eligibility criteria, quality appraisal, data extraction, and synthesis. The method for part B was informed by a scoping review and systematic reviews of evidence use by municipal policy-makers [9, 34, 35]. The Supplementary material of this paper contains additional information about definitions, search strategy, quality appraisal, narrative synthesis, thematic analysis, and development of a theory of change.

Search Strategy

The search strategy was reported in the protocol and part A results and is thus only minimally discussed here with further information available in the Supplementary material, section 1.1.2 [9, 10]. The search was conducted from Jan 27, 2016 to Feb 24, 2016, using seven bibliographic databases, grey literature searches and key journal hand searches. Google Advanced searches were conducted on six urban planning practitioner and health promoting organizations’ websites and the Internet using specified search terms in line with the search strategy for databases. These websites were selected to find either UHI tools or studies about their use in municipal built environment policy-making, building on initial findings from the scoping review.

The search terms were identified through the scoping review and included key terms for (1) urban environment (e.g., urban, metropolitan, city, environment, neighbourhood, community), (2) health and related concepts (e.g., determinant, public, health, well-being, wellness, quality, livability) and (3) indicator (e.g., benchmark, tool, indicator, index, indices, measure, metric, profile, assessment, score, standard).

Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility for part B required all of the following criteria to be met as described in the protocol:

-

Reports substantive data on views, attitudes or knowledge about the use of an urban health indicator tool in the policy-making or decision-making process, or about the implementation of specific policies, interventions or programmes informed by these (modified from Lorenc et al.) [34]

-

Includes policy and/or decision-makers from one of the following policy fields in local government: housing, transport, urban planning, and regeneration

-

Reports qualitative or quantitative data

-

Published in English (in any country) [9]

Screening and Quality Appraisal

All documents were screened (in Eppi-Reviewer) by HP, and a random sample of 10% of documents were screened by KG at the title and abstract and full paper screening stages. Differences were resolved through discussion. A key point of discussion was whether studies reported substantive data which was interpreted on a case-by-case basis. The researchers looked for information that could be extracted and analyzed beyond a single sentence or paragraph. Studies included in part B were appraised using the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) quality appraisal tool for qualitative studies [36]. The Supplementary material contains additional information and a copy of the completed quality appraisal checklists.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Studies that met the eligibility criteria for part B were included in a narrative synthesis, using the full text of the study for analysis. The narrative synthesis was informed by Popay et al. [37]. The synthesis was developed using textual descriptions, tabulation, semantic coding, thematic analysis, vote-counting as a descriptive tool and subgroup analysis. Data were analyzed using NVivo qualitative data analysis software (QSR International Pty Ltd., version 11.4.3, 2017). Based on Popay et al.’s guidance, data coding sought to inform, and was informed by, a theory of change (ToC) about what worked, for whom and in what circumstances. The ToC was developed iteratively and inductively (described in more detail in Supplementary material, section 1.1.6, including a completed checklist developed by Breuer et al. [38] for reporting ToC development). During inductive data analysis, we developed a distinction between UHI tool development processes as “expert-led” or “participatory” and categorized tools within these groups by comparing details on the UHI tool development process reported by UHI tool producers (see Supplementary material, section 1.1.7). Our primary criterion for distinguishing between expert-led and participatory development processes was whether or not a range of stakeholders were involved in selecting indicators.

Results

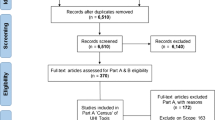

Figure 1 shows the flow of records in the review. As in part A, 9097 records were identified from the bibliographic database, Internet, and journal searches. After duplicates were removed, 6510 titles and abstracts were screened, of which 370 were included in the full-text review. Finally, 10 studies were included in the part B narrative synthesis. A total of 360 studies were excluded on the basis of scope, policy field, language, media type, availability, or not reporting substantive data.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 10 included studies and Table 2 describes the 10 UHI tools described in these studies. Most of the studies (7/10) were case study designs using a range of qualitative data collection methods including participant observation, interviews, document analysis and group discussions. With two exceptions, the studies were written by individuals involved in developing the UHI tool being investigated (for one of the exceptions, this could not be confirmed, the other was reported by independent academics). The majority of the UHI tools (8/10) were used in high income countries (the USA, Australia, the UK, and Belgium) and two were used in lower middle-income countries (India and Kenya). One study gathered perceptions on the potential value of UHI tools in South Africa. Most of the studies were conducted relatively recently (two between 1988 and 2000 and eight between 2008 and 2015). All of the studies addressed the urban planning policy field.

UHI Tool Development

The approach to developing and applying UHI tools, either expert-led or participatory, influenced the value and use of UHI tools. Therefore, a distinction is made between these two approaches when analyzing data and reporting results.

Expert-led UHI tools (4/10) generally followed a technical approach to indicator development, with a focus on environmental health exposures and outcomes (Table 2). Such UHI tools were developed to measure, compare, and assess the urban environment impact on health through translation of research evidence, with recognition of an evidence hierarchy. The community (i.e., the general public) was not central to the development of such tools, although their views may have been incorporated in some way, such as to inform UHI tool domains. Expert-led approaches sometimes involved an iterative process informed by engagement with local government (and other) stakeholders.

In contrast, participatory UHI tools (6/10) were described as emerging from a process of co-production with the community which placed relatively less importance on the hierarchy of evidence defining or validating indicators (Table 2). These participatory processes encouraged a wide range of city stakeholders, including citizens, local government officials, and academic experts to co-define concepts and co-produce indicators through an iterative process of local negotiation, determined by context. Some of these projects involved co-creation of policy and co-monitoring of policy impacts.

The expert-led and participatory characterizations are not absolute and variations among UHI tool processes are recognized. For example, experts technically led the Flemish City Monitor and the San Francisco Indicators Project (SFIP) development, yet multiple stakeholders, including the community, were significantly involved and made fundamental decisions about the process and indicators [39,35,41]. As a result, these projects are viewed as participatory in this study. In contrast, there was engagement with community organizations and government stakeholders to establish indicator domains for Community Indicators Victoria (CIV), but the majority of indicator selection and application was expert-led [42, 43].

Uses and Benefits of UHI Tools

The development and application of UHI tools resulted in a number of benefits that had the potential to improve the built environment to promote health and well-being. Table 3 shows how many studies reported each use/benefit and whether these were achieved through UHI tools characterized by the following: (1) expert-led or participatory approaches and (2) indicator data presented at neighbourhood or city scale. The three uses and benefits outlined below are among the top four from Table 3. These were achieved by expert-led and participatory UHI tool approaches. The benefit of collaboration across stakeholders is discussed in the next section, which led to multiple outcomes beyond those described in Table 3.

Informing policy development was the most widely noted benefit of developing and applying UHI tools. For example, in San Francisco, the UHI tool improved understanding of air quality issues in certain neighbourhoods within the city, which then led to specific policies to reduce ingress of polluted air into new housing [39]. Through dialogue between the city’s planning and public health departments, the public health team were able to understand the planners’ constraints and make appropriate recommendations to reduce the impact of air pollution in new housing.

UHI tools increased community and local government knowledge and capacity to improve urban health. In Cape Town, Lucknow and Calcutta study participants identified a virtuous cycle of community involvement in indicators to raise awareness and thereby improve city services [44]. In Bristol, knowledge gained by the community was described as “one of the most important outcomes” although it was “more of an unintended consequence” [45]. In San Francisco, indicators helped “citizens to participate more knowledgeably in decisions” [39] and “unequivocally increased Council member understanding of how human health is impacted by development” [40].

Monitoring was consistently described as a valuable function of UHI tools, as either a task for local government officials or a participatory governance process. The latter was promoted by Corburn and Cohen as part of an adaptive management process [30]. UHI tools with longitudinal data allowed local officials to observe trends and act early when problems arose. Monitoring through Bristol’s UHI tool “improved the targeting of investment in graffiti removal to prioritise Neighbourhood Renewal Areas which then quickly saw positive impacts on public perception” [45].

Benefits of Community Involvement in UHI Tools

Involving communities in developing or using UHI tools resulted in additional outcomes compared to what could be achieved without their involvement. These could be achieved through either expert-led or participatory processes, although the latter were likely to have greater community involvement. There were four key benefits of community involvement in UHI tool development.

First, community involvement led to increased participation and sense of power in urban governance. Corburn et al. described the outcome of workshops with the community and city staff as being “crucial for generating policy solutions and transforming the governance relationships between the city and its residents” [46]. The indicator process in San Francisco “promote[d] meaningful public involvement in land use policy making by making explicit competing interests and facilitating consensus” [40]. Expert-led UHI tools also facilitated community involvement in planning processes. For example, through using Seattle’s HLA, “[c]ommunity members were engaged in the planning process in a genuine and productive way” [47].

Second, community input in UHI tools increased balancing of expert and lay knowledge claims and representation of community needs to policy-makers. Diverse stakeholders brought their own knowledge and priorities to UHI tool development. Project leaders determined how different perspectives and knowledge claims should be elicited and treated when developing indicators. For example, in San Francisco, “the quality of participation likely enhanced the interpretability, meaning, and relevance of indicators for stakeholders and contributed to the indicators’ usefulness in supporting stakeholders’ demands in the process of policy making” [39]. A wide range of stakeholders were consulted, contributed views, and made decisions, with the public health department acting as a final arbiter to interpret this range of information and apply indicator results with the city’s planning department.

Third, community participation in UHI tools created or exposed tensions between stakeholders which opened opportunities to negotiate solutions and build consensus. Tensions were related to conflicting views on how environment, land use, and health issues should be addressed through built environment policies. They were also related to power imbalances among actors and differing views on how indicators would be used to redress these. In Lucknow and Calcutta, the indicator development process created a positive opportunity to discuss issues and gain new perspectives about pre-existing tensions between residents, planners, and service providers. The process of developing indicators created opportunities for residents and government representatives to move beyond “stereotypic views” and “discuss common concerns … to improve the understanding of each other’s needs and constraints” [44]. This new shared understanding was found to have improved dialogue and thereby improved service delivery [44]. A very similar story was relayed about SFIP where the UHI tool was purposefully developed in the context of existing conflict to “foster dialogue among diverse stakeholders to help bridge the multiple and often competing interests placing demands on development” [40]. However, some stakeholders felt that SFIP was “stacked against development interests” and would therefore be used in attempts to stop new development [40].

Finally, the development and use of UHI tools with community members improved the knowledge of residents and city agencies about the varied environmental causes of health impacts, leading to examples of “health in all policies” and “whole-of-society” approaches, as defined by Kickbusch and Gleicher [48]. For example, SFIP increased knowledge and led some participants “to apply public health arguments and evidence in public policy dialogues on housing, economic, and environmental issues,” essentially resulting in a health in all policies approach [40]. In relation to whole-of-society approaches, in Seattle, the focus on residents’ views provided through application of the UHI tool “led to the inclusion of more actions that lie outside the realm of city departments” [47].

Facilitators and Barriers of UHI Tool Development and Use

There were a number of facilitators and barriers to both developing and applying UHI tools that affected their ability to influence policy- and decision-making (Table 4). The facilitators and barriers spanned technical, political, knowledge, and organizational factors. Facilitators listed under a particular heading in Table 4 (e.g., knowledge) may have helped to overcome barriers of that same type or other types (e.g., political). These facilitators and barriers are further explained through the theory of change.

Relations between Characteristics and Use of UHI Tools

Several insights were identified by combining quantitative and qualitative data from parts A and B. First, a number of UHI tool uses and benefits were more commonly achieved through UHI tools which measured data at the neighbourhood and city-scale, compared to those which only measured city-scale data (see below). Second, despite the large number of UHI tools which mapped data spatially (64/145 [44.1%] in part A and 4/10 in part B) and the supposed benefits of presenting data on maps in the literature, using maps was not frequently mentioned in the studies of UHI tool development and application. Third, only one UHI tool (Places Rated Almanac) reported data through an index, or composite indicator, and the study concluded that it was not useful for built environment policy- and decision-making. See the Supplementary material for further details.

Of the part B UHI tools, 60% (6/10) measured data at the neighbourhood (and city) scale, compared to 59.3% (86/145 tools) of the part A UHI tools. Some outcomes of developing and applying UHI tools were more frequently achieved by the neighbourhood scale tools than the city scale tools, such as creating awareness of urban health issues, supporting monitoring and providing evidence of health or spatial inequalities (Table 3).

Addressing Complexity with UHI Tools

Complexity was recognized as a feature of both policy-making and urban health systems with several examples of how the use of UHI tools may address these challenges. Two studies provided specific solutions, including an adaptive management approach and underpinning UHI tools with a normative or systems framework (described in the Supplementary material) [30, 41]. Based on their experience in India and South Africa, Hunt and Lewin were not convinced that UHI tools could influence the “complexity of the policy process,” identifying political and economic constraints as key barriers [44].

Appendix Table 6 outlines seven characteristics of complexity in urban health systems identified in the academic literature (adapted from Pineo et al. [11]) and summarizes potential solutions identified in the systematic review (parts A and B) and from the authors (marked by an asterisk).

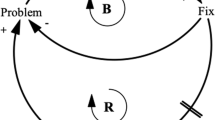

Theory of Change

Figure 2 is a high-level visual summary of our ToC. The visual shows four quadrants for inputs, activities, outputs and outcomes which are not necessarily sequential (i.e., occurring clockwise). Each quadrant contains key characteristics rather than a comprehensive description. The quadrants are affected by the external ring of contextual factors. Table 5 provides more detail about the ToC, differentiating between participatory and expert-led UHI tools. Many factors were common to both approaches, such as the requirement of resources and data. However, the importance and function of inputs and activities varied across the approaches. Furthermore, participatory approaches more often had the crucial difference of involving the community alongside a wide group of stakeholders which required different inputs (such as places to meet and buy-in from stakeholders) and activities (such as balancing competing knowledge claims and negotiating pre-existing conflicts or tensions).

Both participatory and expert-led UHI tool processes shared outputs such as increasing stakeholder knowledge. However, participatory processes (typically with greater community involvement) resulted in additional outputs such as a wider group of stakeholders gaining and applying new knowledge of urban health issues across multiple policies and activities (health in all policies and whole-of-society approaches), increased collaboration and communication among stakeholders, and policies that more directly responded to residents’ needs.

Discussion

This study has contributed new knowledge about the use of UHI tools using a mixed methods systematic review. First, we found that UHI tools in our sample were developed using a combination of research evidence and residents’ knowledge and represented a middle ground between opposing epistemological characterizations of indicators as either rational tools or socially constructed artefacts. Second, our findings contradict the dominant view of indicator use in policy-making as a linear process, identifying a range of technical, political, knowledge, organizational and contextual factors that impact UHI tool use (shown through the ToC). Third, participatory processes of UHI tool development brought about useful outcomes for urban environment policy- and decision-makers; however, this was not UHI tools’ only path of influence. Fourth, community involvement in UHI tools (typically achieved by participatory approaches) resulted in uses and benefits that would support health in all policies and whole-of-society approaches to governing healthy cities, such as creating distributed awareness and knowledge of urban health issues. Fifth, UHI tool producers proposed a range of techniques to address urban health complexity characteristics; however, some were cautious as to whether such methods can influence the complexity of policy- and decision-making. Finally, in combining data from parts A and B, the review has shown that potentially important UHI tool features, such as neighbourhood-scale data, were influential in the use of indicators by built environment policy- and decision-makers. Our findings support UHI tool producers with better understanding of how indicators influence policy (e.g., through the ToC) which could shape future UHI tool development and improve their impact.

We believe this is the first narrative synthesis of studies on the use of UHI tools, the first study on this topic to use the sequential explanatory mixed methods design and the first ToC of the use and benefits of UHI tools. We have contributed new synthesized knowledge on what works, for whom, and in what circumstances. The protocol was published prior to conducting the review and followed best practice procedures for systematic review design and reporting [9, 49, 50]. The synthesis procedure followed best practice guidance [37]. The review covered a range of income settings; however, studies were predominately in high income settings.

The review was limited to English language publications, potentially excluding UHI tools from non-English language countries. The included studies were primarily case studies (7/10) conducted by the same individuals who developed the UHI toolsFootnote 1 and therefore may have overemphasized positive benefits of using indicators. The study designs were heterogeneous, and there were few available studies. One included report was not a peer-reviewed journal paper. In conducting this review, all studies and reports which met the eligibility criteria were included, regardless of methods and risk of bias. Our ToC is only representative of the included studies and could be improved through wider consultation with indicator producers and users.

Our narrative synthesis identified a middle ground for debates about the epistemological basis of indicators. UHI tool producers combined rationalist and constructivist approaches to indicator selection. Evidence-based indicators (i.e., scientific evidence) were supported and desired by all stakeholders. Regardless of the type of knowledge claim underpinning UHI tools, some stakeholders were suspicious of the use of such metrics for justifying built environment policies and decisions. For example, some politicians and developers argued against indicators which could be used to block (economic) development [40, 41]. Given the potential value of UHI tools in representing community interests in planning and development, particularly those related to equity, it is essential to understand how these interests may be subordinated to more powerful actors in urban governance. Future research is needed to explore the weight of community-informed indicators in decision-making.

We have previously discussed whether similarities across UHI tools supported an argument for greater indicator standardization to reduce duplication of research efforts [10]. In relation to sustainability and social indicators, scholars have argued that the role of indicators within governance processes and the process of developing indicators is equally or more important than the resulting indicator data [12, 13]. Our ToC shows the value of participatory processes and contradicts the dominant view of indicator use as a linear process. A number of factors spanning technical, organizational, political, and knowledge (and wider context) were influential in determining whether indicators could support policy- and decision-making. The processes of indicator development and application with diverse stakeholders (including the community) were integral to achieving benefits such as negotiation and consensus-building, balancing knowledge claims, supporting health in all policies and whole-of-society approaches, community participation, and local learning. Standardization would potentially risk the achievement of such benefits. However, we support our previous assertion that further research could identify whether a global set of evidence-based urban health indicators could be a starting point for local efforts, which would continue through a process of local prioritization and application of indicators using local data [10].

Community representatives sought to empower themselves by using UHI tools as a mechanism to exert influence in urban governance (such as to resist development or argue for funding) on the basis of health-related arguments. However, UHI tools were not necessarily viewed by some developers and politicians as a legitimate input to policy- and decision-making [40, 41]. The validity of UHI tools appears to have been contested in settings where stakeholders felt that existing powers and governance mechanisms were at risk of being disrupted through the use of indicators. The Pastille Consortium argued that conflict among actors reduced the likelihood that indicators would inform policy [51]. However, Innes and Booher recognize the likelihood of conflict in complex urban governance challenges and the value of raising diverse views to collaboratively develop solutions [21]. Our review found cases where UHI tool processes were used to reduce conflict among actors by creating opportunities for discussion and negotiation that would not have happened otherwise. The role of UHI tools in supporting diverse actors to address power imbalances in urban governance is an area for further research.

The simplification and communication of complex phenomena are often cited as key benefits of indicators, although scholars have pointed to the potential risks for policy-making including political manipulation of indicators and inappropriate policy responses [30, 52,50,54]. The review (parts A and B) identified a number of strategies in indicator development and application that may support policy- and decision-makers with complexity. However, some study authors evaluated in this review felt that UHI tools may not be effective in influencing the complex policy- and decision-making process [41, 44]. Further research is required to investigate the value of UHI tools in relation to simplifying, representing or addressing complexity in urban health and policy-making.

Change history

26 December 2019

There were errors in this article as originally published.

Notes

We could not confirm whether Shepherd and McMahon [45] (one out of seven case studies) were involved in developing the (Bristol) quality of life indicators.

References

Marmot M, Bell R. The sustainable development goals and health equity. Epidemiology. 2018;29(1):5–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000773.

de Leeuw E, Green G, Spanswick L, Palmer N. Policymaking in European healthy cities. Health Promot Int. 2015;30(suppl_1):i18–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dav035.

Klopp JM, Petretta DL. The urban sustainable development goal: indicators, complexity and the politics of measuring cities. Cities. 2017;63:92–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.12.019.

Giles-Corti B, Vernez-Moudon A, Reis R, Turrell G, Dannenberg AL, Badland H, et al. City planning and population health: a global challenge. Lancet. 2016;388(10062):2912–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30066-6.

McCarney PL, McGahan AM. The case for comprehensive, integrated, and standardized measures of health in cities. In: Ahn R, Burke TF, McGahan AM, editors. Innovating for healthy urbanization. New York: Springer US; 2015. p. 307–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-7597-3_14.

Landis JD, Sawicki DS. A Planner’s Guide to the Places Rated Almanac. J Am Plann Assoc. 1988;54:336–46.

Dora C, Haines A, Balbus J, Fletcher E, Adair-Rohani H, Alabaster G, et al. Indicators linking health and sustainability in the post-2015 development agenda. Lancet. 2015;385(9965):380–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60605-X.

Lowe M, Whitzman C, Badland H, et al. Planning Healthy, Liveable and Sustainable Cities: How Can Indicators Inform Policy? Urban Policy Res. 2015;33:131–44.

Pineo H, Glonti K, Rutter H, Zimmermann N, Wilkinson P, Davies M. Characteristics and use of urban health indicator tools by municipal built environment policy and decision-makers: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2017;6:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0406-x.

Pineo H, Glonti K, Rutter H, Zimmermann N, Wilkinson P, Davies M. Urban health indicator tools of the physical environment: a systematic review. J Urban Health. 2018;95(5):613–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-018-0228-8.

Pineo H, Zimmermann N, Cosgrave E, Aldridge RW, Acuto M, Rutter H. Promoting a healthy cities agenda through indicators: development of a global urban environment and health index. Cities Health. 2018;2:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2018.1429180.

Innes JE, Booher DE. Indicators for sustainable communities: a strategy building on complexity theory and distributed intelligence. Plan Theory Pract. 2000;1(2):173–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350020008378.

Rydin Y, Holman N, Wolff E. Local sustainability indicators. Local Environ. 2003;8(6):581–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354983032000152707.

Glouberman S, Gemar M, Campsie P, et al. A Framework for Improving Health in Cities: A Discussion Paper. J Urban Health. 2006;83:325–38.

Wong C. Indicators for urban and regional planning: the interplay of policy and methods. Wong: Abingdon, England 2006.

Block T, Van Assche J, Vandewiele D, De Rynck F, Reynaert H. Indicator set for Sustainable Urban Development. City Monitor for Liveable and Sustainable Flemish Cities. Brussels: Urban Policy of the Flemish Government, 2008. http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-603841. Accessed Feb 13, 2019.

AARP. AARP Livability Index: Web-based Tool to Measure Community Livability. AARP. https://livabilityindex.aarp.org/. Accessed Feb 15, 2016.

Sébastien L, Bauler T, Lehtonen M. Can indicators bridge the gap between science and policy? An exploration into the (non)use and (non)influence of indicators in EU and UK policy making. Nat Cult. 2014;9(3):316–43.

Talen E. Pedestrian access as a measure of urban quality. Plan Pract Res. 2002;17(3):257–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/026974502200005634.

McGill E, Egan M, Petticrew M, Mountford L, Milton S, Whitehead M, et al. Trading quality for relevance: non-health decision-makers’ use of evidence on the social determinants of health. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e007053.

Innes JE, Booher DE. Planning with complexity : an introduction to collaborative rationality for public policy. Innes and Booher: London, England 2010.

Oliver K, Lorenc T, Innvaer S. New directions in evidence-based policy research: a critical analysis of the literature. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014;12(34):1–11.

Webster P, Sanderson D. Healthy cities indicators—a suitable instrument to measure health? J Urban Health. 2013;90(S1):52–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-011-9643-9.

Sterman JD. Learning from evidence in a complex world. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(3):505–14. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.066043.

Sterman J. Business dynamics: systems thinking and modeling for a complex world. Boston: Irwin/McGraw-Hill; 2000.

Luke DA, Stamatakis KA. Systems science methods in public health: dynamics, networks, and agents. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33(1):357–76. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101222.

Northridge DME, Sclar DED, Biswas MP. Sorting out the connections between the built environment and health: a conceptual framework for navigating pathways and planning healthy cities. J Urban Health. 2003;80(4):556–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jtg064.

Rydin Y, Bleahu A, Davies M, Dávila JD, Friel S, de Grandis G, et al. Shaping cities for health: complexity and the planning of urban environments in the 21st century. Lancet. 2012;379(9831):2079–108.

Gatzweiler FW, Reis S, Zhang Y, Jayasinghe S. Lessons from complexity science for urban health and well-being. Cities Health. 2018;1(2):210–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2018.1448551.

Corburn J, Cohen AK. Why we need urban health equity indicators: integrating science, policy, and community. PLoS Med. 2012;9(8):e1001285. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001285.

Lawrence RJ. Urban environmental health indicators: appraisal and policy directives. Rev Environ Health. 2008;23(4):299–325. https://doi.org/10.1515/REVEH.2008.23.4.299.

Rutter H, Savona N, Glonti K, Bibby J, Cummins S, Finegood DT, et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet. 2017;390(10112):2602–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31267-9.

Ivankova NV, Creswell JW, Stick SL. Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: from theory to practice. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05282260.

Lorenc T, Tyner EF, Petticrew M, Duffy S, Martineau FP, Phillips G, et al. Cultures of evidence across policy sectors: systematic review of qualitative evidence. Eur J Pub Health. 2014;24(6):1041–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku038.

Oliver K, Innvar S, Lorenc T, Woodman J, Thomas J. A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):1–12.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methods for the development of NICE public health guidelines (Third Edition). 2012. http://www.nice.org.uk/aboutnice/howwework/developingnicepublichealthguidance/publichealthguidanceprocessandmethodguides/public_health_guidance_process_and_method_guides.jsp. Accessed 13 Nov 2015.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Prod ESRC Methods Programme Version 2006;1:b92.

Breuer E, Lee L, De Silva M, Lund C. Using theory of change to design and evaluate public health interventions: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2015;11(63):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0422-6.

Bhatia R. Case study: San Francisco’s use of neighborhood indicators to encourage healthy urban development. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(11):1914–22. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0661.

Farhang L, Bhatia R, Scully CC, Corburn J, Gaydos M, Malekafzali S. Creating tools for healthy development: case study of San Franciscoʼs eastern neighborhoods community health impact assessment. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(3):255–65. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PHH.0000316484.72759.7b.

Van Assche J, Block T, Reynaert H. Can community indicators live up to their expectations? The case of the Flemish City monitor for livable and sustainable urban development. Appl Res Qual Life. 2010;5(4):341–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-010-9121-7.

Davern MT, West S, Bodenham S, Wiseman J. Community indicators in action: using indicators as a tool for planning and evaluating the health and wellbeing of a community. In: Sirgy MJ, Phillips R, Rahtz D, editors. Community quality-of-life indicators: best cases V. Community quality-of-life indicators. Netherlands: Springer; 2011. p. 319–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0535-7_14.

Davern MT, Gunn L, Giles-Corti B, David S. Best practice principles for community indicator systems and a case study analysis: how community indicators Victoria is creating impact and bridging policy, practice and research. Soc Indic Res. 2017;131(2):567–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1259-8.

Hunt C, Lewin S. Exploring decision-making for environmental health services: perspectives from four cities. Rev Environ Health. 2000;15(1–2):187–206. https://doi.org/10.1515/REVEH.2000.15.1-2.187.

Shepherd S, McMahon S. The importance of local information: quality of life indicators in Bristol. In: Sirgy PMJ, Phillips DR, Rahtz PDR, editors. Community quality-of-life indicators: best cases IV. Community quality-of-life indicators. Netherlands: Springer; 2009. p. 111–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2243-1_5.

Corburn J, Curl S, Arredondo G, Malagon J. Health in all urban policy: city services through the prism of health. J Urban Health. 2014;91(4):623–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-014-9886-3.

Lerman S. Seattle healthy living assessment: pilot implementation report. 2011. http://www.seattle.gov/dpd/cs/groups/pan/@pan/documents/web_informational/dpdd016767.pdf. Accessed 23 Mar 2017.

Kickbusch I, Gleicher D. Governance for health in the 21st century. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Kickbusch and Gleicher: Copenhagen, Denmark Denmark; 2012.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349:g7647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647.

Moher D. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135.

Pastille Consortium. Indicators into action: local sustainability indicator sets in their context. London: London School of Economics; 2002. http://www.communityindicators.net/system/publication_pdfs/14/original/Pastille_Commission_2005.pdf?1323963473. Accessed 26 Apr 2017

Hardi P, Pintér L. City of Winnipeg quality-of-life indicators. In: Sirgy P of MMJ, Rahtz P of MD, Swain PSD, editors. Community quality-of-life indicators. Social Indicators Research Series. Springer Netherlands; 2006:127–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-4625-4_6

Saisana M, Tarantola S. State-of-the-art report on current methodologies and practices for composite Indicator development. Ispra, Italy: European Commission–Joint Research Centre. Saisana and Tarantola: Ispra, Italy 2002.

Decoville A. Use and misuse of indicators in spatial planning: the example of land take. Plan Pract Res. 2018;3(1):70–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2017.1378981.

Acknowledgements

HP was funded through an industry-sponsored PhD sponsored by the Building Research Establishment Ltd and the BRE Trust.

Funding

This research was part-funded by an industry-sponsored PhD funded by the Building Research Establishment (BRE) and BRE Trust.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 185 kb)

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Pineo, H., Glonti, K., Rutter, H. et al. Use of Urban Health Indicator Tools by Built Environment Policy- and Decision-Makers: a Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. J Urban Health 97, 418–435 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-019-00378-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-019-00378-w