Abstract

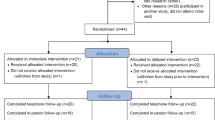

Food insecurity is associated with negative chronic health outcomes, yet few studies have examined how providing medically appropriate food assistance to food-insecure individuals may improve health outcomes in resource-rich settings. We evaluated a community-based food support intervention in the San Francisco Bay Area for people living with HIV and/or type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) to determine the feasibility, acceptability, and potential impact of the intervention on nutritional, mental health, disease management, healthcare utilization, and physical health outcomes. The 6-month intervention provided meals and snacks designed to comprise 100% of daily energy requirements and meet nutritional guidelines for a healthy diet. We assessed paired outcomes at baseline and 6 months using validated measures. Paired t tests and McNemar exact tests were used with continuous and dichotomous outcomes, respectively, to compare pre-post changes. Fifty-two participants (out of 72 initiators) had both baseline and follow-up assessments, including 23 with HIV, 24 with T2DM, and 7 with both HIV and T2DM. Median food pick-up adherence was 93%. Comparing baseline to follow-up, very low food security decreased from 59.6% to 11.5% (p < 0.0001). Frequency of consumption of fats (p = 0.003) decreased, while frequency increased for fruits and vegetables (p = 0.011). Among people with diabetes, frequency of sugar consumption decreased (p = 0.006). We also observed decreased depressive symptoms (p = 0.028) and binge drinking (p = 0.008). At follow-up, fewer participants sacrificed food for healthcare (p = 0.007) or prescriptions (p = 0.046), or sacrificed healthcare for food (p = 0.029). Among people with HIV, 95% adherence to antiretroviral therapy increased from 47 to 70% (p = 0.046). Among people with T2DM, diabetes distress (p < 0.001), and perceived diabetes self-management (p = 0.007) improved. Comprehensive, medically appropriate food support is feasible and may improve multiple health outcomes for food-insecure individuals living with chronic health conditions. Future studies should formally test the impact of medically appropriate food support interventions for food-insecure populations through rigorous, randomized controlled designs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- ARV:

-

Antiretroviral

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- GED:

-

General Educational Development

- HbA1c:

-

Glycated hemoglobin

- HFSSM:

-

Household Food Security Survey Module

- PDSMS:

-

Perceived Diabetes Self-Management Scale

- POH:

-

Project Open Hand

- SNAP:

-

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

- SSDI:

-

Social Security Disability Income

- SRO:

-

Single room occupancy

- SSI:

-

Supplemental Security Income

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- UCSF:

-

University of California, San Francisco

References

Ivers LC, ed. Food Insecurity and Public Health. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; 2015.

Seligman HK, Schillinger D. Hunger and socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363(1): 6–9.

Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt M, Gregory C, Singh A. Household food security in the United States in 2015. ERR-215: United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service 2016.

Seligman HK, Bindman AB, Vittinghoff E, et al. Food insecurity is associated with diabetes mellitus: results from the National Health Examination and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002. J Gen Intern Med. 2007; 22(7): 1018–1023.

Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010; 140(2): 304–310.

Palar K, Laraia B, Tsai AC, Johnson M, Weiser SD. Food insecurity is associated with HIV, sexually transmitted infections and drug use among men in the United States. AIDS. 2016; 30(9):1457–1465.

Vogenthaler NS, Kushel MB, Hadley C, et al. Food Insecurity and Risky Sexual Behaviors Among Homeless and Marginally Housed HIV-Infected Individuals in San Francisco. AIDS and Behavior. 2012:1–6.

Shannon K, Kerr T, Milloy M-J, et al. Severe food insecurity is associated with elevated unprotected sex among HIV-seropositive injection drug users independent of HAART use. AIDS. 2011; 25(16): 2037–2042.

Kalichman S, Cherry C, Amaral C, et al. Health and treatment implications of food insufficiency among people living with HIV/AIDS, Atlanta. Georgia J Urban Health. 2010; 87(4): 1–11.

Weiser SD, Yuan C, Guzman D, et al. Food insecurity and HIV clinical outcomes in a longitudinal study of homeless and marginally housed HIV-infected individuals in San Francisco. AIDS. 2013; 27(18): 2953–2958.

McMahon JH, Wanke CA, Elliott JH, et al. Repeated assessments of food security predict CD4 change in the setting of antiretroviral therapy. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndromes. 2011; 58(1): 60–63.

Weiser S, Frongillo EA, Ragland K, et al. Food insecurity is associated with incomplete HIV RNA suppression among homeless and marginally housed HIV-infected individuals in San Francisco. J Gen Intern Med. 2009; 24(1): 14–20.

Wang EA, McGinnis KA, Fiellin DA, et al. Food Insecurity is associated with poor virologic response among HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral medications. J Gen Intern Med. 2011; 26(9): 1012–1018.

Weiser S, Tsai AC, Gupta R, et al. Food insecurity is associated with morbidity and patterns of healthcare utilization among HIV-infected individuals in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2012; 26(1): 67–75.

Weiser S, Fernandes K, Brandson E, et al. The association between food insecurity and mortality among HIV-infected individuals on HAART. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009; 52(3): 342–349.

Seligman HK, Davis TC, Schillinger D, et al. Food insecurity is associated with hypoglycemia and poor diabetes self-management in a low-income sample with diabetes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010; 21(4): 1227.

Seligman HK, Jacobs EA, López A, et al. Food insecurity and glycemic control among low-income patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012; 35(2): 233–238.

Nelson K, Brown ME, Lurie N. Hunger in an adult patient population. JAMA. 1998; 279(15): 1211–1214.

Weiser SD, Young SL, Cohen CR, et al. Conceptual framework for understanding the bidirectional links between food insecurity and HIV/AIDS. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011; 94(suppl): 1729S–1739S.

Weiser SD, Palar K, Hatcher A, Young S, Frongillo EA, Laraia B. Food Insecurity and Health: A Conceptual Framework. In: Ivers LC, ed. Food Insecurity and Public Health: CRC Press; 2015:23–50.

Smith R, Rossetto K, Peterson B. A meta-analysis of disclosure of one’s HIV-positive status, stigma and social support. AIDS Care. 2008; 20(10): 1266–1275.

Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: a systematic review and analysis. Nutr Rev. 2015; 73(10): 643–660.

DiSantis KI, Grier SA, Odoms-Young A, et al. What “price” means when buying food: insights from a multisite qualitative study with Black Americans. Am J Public Health. 2013; 103(3): 516–522.

Drewnowski A, Aggarwal A, Hurvitz PM, et al. Obesity and supermarket access: proximity or price? Am J Public Health. 2012; 102(8): e74–80.

Weinfield NS, Mills G, Borger C, et al. Hunger in America 2014: National Report Prepared for Feeding America. Westat and the Urban Institute for Feeding America 2014.

California – 2015 State Health Profile: HIV/AIDS Epidemic: CDC National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention; 2015.

Trenkamp B, Wiseman M. The Food Stamp Program and Supplemental Security Income, Social Security Bulletin, Vol. 67, No. 4. Office of Disability and Income Assistance Policy, Office of Retirement and Disability Policy, Social Security Administration 2007.

Ellwood M, Downer S, Broad Leib E, et al. Food Is Medicine: Opportunities in Public and Private Health Care for Supporting Nutritional Counseling and Medically-Tailored. Home-Delivered Meals, Harvard Law School, Center For Health Law & Policy Innovation. 2014.

Seligman HK, Lyles C, Marshall MB, et al. A pilot food bank intervention featuring diabetes-appropriate food improved glycemic control among clients in three states. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015; 34(11): 1956–1963.

Martin KS, Wu R, Wolff M, et al. A novel food pantry program: food security, self-sufficiency, and diet-quality outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2013; 45(5): 569–575.

Habicht JP, Victora CG, Vaughan JP. Evaluation designs for adequacy, plausibility and probability of public health programme performance and impact. Int J Epidemiol. 1999; 28(1): 10–18.

Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security, Revised 2000. Alexandria, VA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; 2000.

Thompson FE, Midthune D, Subar AF, et al. Performance of a short tool to assess dietary intakes of fruits and vegetables, percentage energy from fat and fibre. Public Health Nutr. 2004; 7(8): 1097–1105.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16(9): 606–613.

Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, et al. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007; 31(7): 1208–1217.

Bunn JY, Solomon SE, Miller C, et al. Measurement of stigma in people with HIV: a reexamination of the HIV Stigma Scale. AIDS Educ Prev. 2007; 19(3): 198–208.

Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001; 24(6): 518–529.

Garcia de Olalla P, Knobel H, Carmona A, et al. Impact of adherence and highly active antiretroviral therapy on survival in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002; 30(1): 105–110.

Bangsberg DR, Perry S, Charlebois ED, et al. Non-adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy predicts progression to AIDS. AIDS. 2001; 15(9): 1181–1183.

Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Earles J, et al. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the diabetes distress scale. Diabetes Care. 2005; 28(3): 626–631.

Wallston KA, Rothman RL, Cherrington A. Psychometric properties of the perceived diabetes self-management scale (PDSMS). J Behav Med. 2007; 30(5): 395–401.

Center of Excellence for Transgender Health. Recommendations for Inclusive Data Collection of Trans People in HIV Prevention, Care & Services. University of California, San Francisco. Available at: http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/trans?page=lib-data-collection. Accessed July 22, 2016.

Food is Medicine: Achieving the Triple Aim through Medically Tailored Nutrition Congressional Briefing. The Food is Medicine Coalition. Washington, DC; March 16, 2016.

Martinez H, Palar K, Linnemayr S, et al. Tailored nutrition education and food assistance improve adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy: evidence from Honduras. AIDS Behav. 2014; 18(5S): 566–577.

Cantrell R, Sinkala M, Megazinni K, et al. A pilot study of food supplementation to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy among food-insecure adults in Lusaka, Zambia. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008; 49(2): 190–195.

Aidala A, Yomogida M, Vardy Y. Food and Nutrition Services, HIV Medical Care, and Health Outcomes: Community Health Advisory & Information Network (CHAIN), Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University.

Gurvey J, Rand K, Daugherty S, et al. Examining health care costs among MANNA clients and a comparison group. J Prim Care Community Health. 2013; 4(4): 311–317.

Amorosa V, Synnestvedt M, Gross R, et al. A tale of 2 epidemics: the intersection between obesity and HIV infection in Philadelphia. JAIDS J Acquir Immune DeficSyndr. 2005; 39(5): 557.

Crum-Cianflone N, Roediger MP, Eberly L, et al. Increasing rates of obesity among HIV-infected persons during the HIV epidemic. PLoS One. 2010; 5(4): e10106.

Palar K, Derose K, Linnemayr S, et al. Impact of food support on food security and body weight among HIV antiretroviral recipients in Honduras: a pilot intervention trial AIDS Care. 2015; 27(4): 409–415.

Li R, Bilik D, Brown MB, et al. Medical costs associated with type 2 diabetes complications and comorbidities. Am J Manag Care. 2013; 19(5): 421–430.

Weiser SD, Hatcher A, Frongillo EA, et al. Food insecurity is associated with greater acute care utilization among HIV-infected homeless and marginally housed individuals in San Francisco. J Gen Intern Med. 2013; 28(1): 91–98.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2014 Hospital Adjusted Expenses per Inpatient Day by Ownership. Available at: http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/expenses-per-inpatient-day-by-ownership/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Accessed Sept. 14, 2016.

Whittle HJ, Palar K, Hufstedler LL, et al. Food insecurity, chronic illness, and gentrification in the San Francisco Bay Area: an example of structural violence in United States public policy. Soc Sci Med. 2015; 143: 154–161.

Acknowledgements

We deeply thank our research participants for sharing their experiences and time with this study. We also thank the Project Open Hand staff and Food = Medicine leadership team for their hard work, dedication, and collaboration. Finally, we thank student interns Irene Ching and Ajikarunia Palar for assisting with data collection, preliminary analyses, and data entry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Financial Support

Project Open Hand (POH) provided funding for this study as an external evaluation, but had no role in data collection or analysis, nor in scientific interpretation of the data. Funding from Burke Global Health supported student and intern participation in data collection. The authors acknowledge the following sources of salary support: NIH/NIDDK K01DK107335 (Dr. Palar) and NIH/NIMH R01MH095683 (Dr. Weiser).

Conflict of Interest

K Palar, T Napoles, LL Hufstedler, H Seligman, FM Hecht, EA Frongillo, and SD Weiser report no conflicts of interest. M Ryle and K Madsen are current POH employees; S Pitchford was a POH employee at the time of the study.

Additional information

Kartika Palar and Tessa Napoles share co-first authorship.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Palar, K., Napoles, T., Hufstedler, L.L. et al. Comprehensive and Medically Appropriate Food Support Is Associated with Improved HIV and Diabetes Health. J Urban Health 94, 87–99 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-016-0129-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-016-0129-7