Abstract

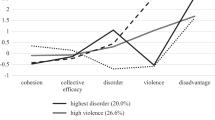

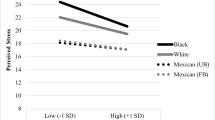

Neighborhood stressors are associated with depressive symptoms and are more likely to be experienced in poor, non-White neighborhoods. Neighborhood stress process theory suggests that neighborhood stressor affect mental health through personal coping resources, such as mastery. Mastery is thought to be both a pathway and a buffer of the ill effects of neighborhood stressors. This research examines the neighborhood stress process with a focus on racial and ethnic differences in the relationship between neighborhood stressors, mastery, and depressive symptoms in a multi-ethnic sample of Chicago residents. Findings suggest race-specific effects on depressive symptoms. Mastery is found to be a pathway from neighborhood stressors to depressive symptoms but not a buffer against neighborhood stressors. Mastery is most beneficial to Whites and those living in low stress neighborhoods.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Pearlin LI, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, Mullan JT. The stress process. J Health Soc Behav. 1981; 22(4): 337–356.

Aneshensel CS. Neighborhood as a social context of the stress process. In: Avison WR, Aneshensel CS, Schieman S, Wheaton B, eds. Advances in the conceptualization of the stress process: essays in honor of Leonard I. Pearlin. New York, NY: Springer; 2010: 35–52.

Kim D. Blues from the neighborhood? Neighborhood characteristics and depression. Epidemiol Rev. 2008; 30(1): 101–117.

Mair C, Diez Roux AV, Galea S. Are neighbourhood characteristics associated with depressive symptoms? A review of evidence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008; 62(11): 940–946.

Curry A, Latkin C, Davey-Rothwell M. Pathways to depression: the impact of neighborhood violent crime on inner-city residents in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Soc Sci Med. 2008; 67(1): 23–30.

Hill NE, Herman-Stahl MA. Neighborhood safety and social involvement: associations with parenting behaviors and depressive symptoms among African American and euro-American mothers. J Fam Psychol. 2002; 16(2): 209–219.

Latkin CA, Curry AD. Stressful neighborhoods and depression: a prospective study of the impact of neighborhood disorder. J Health Soc Behav. 2003; 44(1): 34–44.

Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disorder, subjective alienation, and distress. J Health Soc Behav. 2009; 50(1): 49–64.

Gary TL, Stark SA, LaVeist TA. Neighborhood characteristics and mental health among African Americans and whites living in a racially integrated urban community. Health Place. 2007; 13(2): 569–575.

Raudenbush SW, Sampson RJ. Ecometrics: toward a science of assessing ecological settings, with application to the systematic social observation of neighborhoods. Sociol Methodol. 1999; 29(1): 1–41.

Echeverría S, Diez-Roux AV, Shea S, Borrell LN, Jackson S. Associations of neighborhood problems and neighborhood social cohesion with mental health and health behaviors: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Health Place. 2008; 14(4): 853–865.

Mair C, Diez Roux AV, Morenoff JD. Neighborhood stressors and social support as predictors of depressive symptoms in the Chicago community adult health study. Health Place. 2010; 16(5): 811–819.

Massey DS. Segregation and stratification: a biosocial perspective. Du Bois Rev Soc Sci Res Race. 2004; 1(01): 7–25.

Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001; 116: 404–418.

Williams DR, Yan Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health. J Health Psychol. 1997; 2(3): 335–351.

Williams DR. Racial Variations in Adult Health Status: Patterns, Paradoxes and Prospects. In Smelser N, Wilson WJ, Mitchell F, editors. America Becoming: Racial Trends and Their Consequences. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences Press; 2001. Vol. II, pp. 371–410.

Vega WA, Sribney WM. Latino population demographics, risk factors, and depression: a case study of the Mexican American prevalence and services survey. In: Depression in Latinos. Vol 8. Springer US; 2008:1–24. 10.

Dunlop DD, Song J, Lyons JS, Manheim LM, Chang RW. Racial/Ethnic differences in rates of depression among preretirement adults. Am J Public Health. 2003; 93(11): 1945–1952.

South SJ, Deane GD. Race and residential mobility: individual determinants and structural constraints. Soc Forces. 1993; 72(1): 147–167.

Wheaton B, Clarke P. Space meets time: integrating temporal and contextual influences on mental health in early adulthood. Am Sociol Rev. 2003; 68: 680–706.

Schieman S, Pearlin LI, Meersman SC. Neighborhood disadvantage and anger among older adults: social comparisons as effect modifiers. J Health Soc Behav. 2006; 47(2): 156–172.

Schieman S. Residential stability and the social impact of neighborhood disadvantage: a study of gender- and race-contingent effects. Soc Forces. 2005; 83(3): 1031–1064.

Pearlin LI, Schooler C. The structure of coping. J Health Soc Behav. 1978; 19(1): 2–21.

Watkins DC, Hudson DL, Howard Caldwell C, Siefert K, Jackson JS. Discrimination, mastery, and depressive symptoms among African American men. Res Soc Work Pract. 2011; 21(3): 269–277.

Keith VM, Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS. Discriminatory experiences and depressive symptoms among African American women: do skin tone and mastery matter? Sex Roles. 2010; 62(1–2): 48–59.

Christie-Mizell CA, Erickson RJ. Mothers and mastery: the consequences of perceived neighborhood disorder. Soc Psychol Q. 2007; 70(4): 340–365.

Geis KJ, Ross CE. A new look at urban alienation: the effect of neighborhood disorder on perceived powerlessness. Soc Psychol Q. 1998; 61(3): 232–246.

Lincoln KD. Financial strain, negative interactions, and mastery: pathways to mental health among older African Americans. J Black Psychol. 2007; 33(4): 439–462.

Miller B, Rote SM, Keith VM. Coping with racial discrimination assessing the vulnerability of African Americans and the mediated moderation of psychosocial resources. Soc Mental Health. 2013; 3(2): 133–150.

Pudrovska T, Schieman S, Pearlin LI, Nguyen K. The sense of mastery as a mediator and moderator in the association between economic hardship and health in late life. J Aging Health. 2005; 17(5): 634–660.

Schieman S, Meersman SC. Neighborhood problems and health among older adults: received and donated social support and the sense of mastery as effect modifiers. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004; 59(2): S89–S97.

Morenoff JD, Sampson RJ. Violent crime and the spatial dynamics of neighborhood transition: Chicago, 1970–1990. Soc Forces. 1997; 76(1): 31–64.

Sharkey P, Sampson RJ. Destination effects: residential mobility and trajectories of adolescent violence in a stratified metropolis. Criminology. 2010; 48(3): 639–681.

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Systematic social observation of public spaces: a new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. Am J Sociol. 1999; 105(3): 603–651.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977; 1(3): 385–401.

Mujahid MS, Diez Roux AV, Morenoff JD, Raghunathan T. Assessing the measurement properties of neighborhood scales: from psychometrics to ecometrics. Am J Epidemiol. 2007; 165(8): 858–867.

Karb RA. Neighborhood social and physical environments and health: examining sources of stress and support in neighborhoods and their relationship with self-rated health, cortisol, and obesity in Chicago. The University of Michigan; USA 2010.

Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Congdon R. HLM 6 for windows [computer software]. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2004.

StataCorp. Stata: Release 11. 2009;11.

Pearlin LI. The stress process revisited. In: Handbook of the sociology of mental health. New York, NY: Springer; 1999:395–415.

Sampson RJ. Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2012.

Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing “neighborhood effects”: social processes and new directions in research. Annu Rev Sociol. 2002; 28: 443–478.

Acknowledgements

The Chicago Community Adult Health study was supported by funds from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P50HD38986 and R01HD050467). The author was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32HD049302). The author would like to thank Steph Robert, Jason Houle, Amy Butler as well as members of the Chicago Community Adult Health research group, especially Jeff Morenoff, Jim House, and Jennifer Ailshire, for comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix Perceived neighborhood stressor component scale items

Appendix Perceived neighborhood stressor component scale items

Questions/data source | |

|---|---|

Neighborhood disorder | How much broken glass or trash on sidewalks and streets do you see in your neighborhood? |

How much graffiti do you see on buildings and walls in your neighborhood? | |

How many vacant or deserted houses or storefronts do you see in your neighborhood? | |

How often do you see people drinking in public places in your neighborhood? | |

How often do you see unsupervised children hanging out on the street in your neighborhood? | |

Neighborhood hazards | How would you rate the quality of air in this neighborhood? |

How often do you see rats, mice, or roaches in your neighborhood? | |

How dangerous do you think traffic is in your neighborhood either to people driving in cars or walking on the street? | |

How noisy would you say your neighborhood is? | |

How often do you encounter potentially toxic substances in your neighborhood? | |

Perceived violence | During the past six months, how often was there a fight in this neighborhood in which a weapon was used? |

A violent argument between neighbors? | |

Gang fights? | |

A sexual assault or rape? | |

A robbery or mugging? | |

Services | How would rate your neighborhood on its accessibility to parks or other areas where people can jog and exercise or kids can play? |

How would you rate the quality of street cleaning and garbage collection in this neighborhood? |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

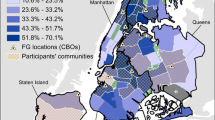

Gilster, M.E. Neighborhood Stressors, Mastery, and Depressive Symptoms: Racial and Ethnic Differences in an Ecological Model of the Stress Process in Chicago. J Urban Health 91, 690–706 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-014-9877-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-014-9877-4