Abstract

Background

Patients with unresectable and metastasized gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) experienced a remarkable improvement of progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) after the introduction of imatinib. Our hypothesis is that the outcomes of treatment with imatinib are even better nowadays compared with the registration trials that were performed two decades ago. To study this, we used real-life data from a contemporary registry.

Methods

A multicenter, retrospective study was performed by exploring clinical data from a prospective real-life clinical database, the Dutch GIST Registry (DGR). Patients with advanced GIST treated with first-line imatinib were included and PFS (primary outcome) and OS (secondary outcome) were analyzed. Results of our study were compared with published results of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 62005 trial, which marked the first era of imatinib in the treatment of GIST.

Results

Overall, 420 of the 435 patients treated with imatinib in the DGR had recorded response evaluation and were included in the analysis. During a median follow-up of 35.0 months (range 2.0–136.0), progression of GIST was eventually observed in 217 patients (51.2%). The DGR cohort showed a longer median PFS (33.0 months, 95% confidence interval [CI] 28.4–37.6) compared with the EORTC 62005 trial (an estimated PFS of 19.5 months). Additionally, the median OS of 68.0 months (95% CI 56.1–80.0) was longer than the exposed median OS (46.8 months) published in the long-term follow-up results of the EORTC 62005 trial (median follow-up duration 10.9 years).

Conclusion

This study provides an update on outcomes of imatinib in the treatment of advanced GIST patients and demonstrates improved clinical outcomes since the first randomized studies of imatinib 2 decades ago. Furthermore, these results represent outcomes in real-world clinical practice and can serve as a reference when evaluating effectiveness of imatinib in patients with advanced GIST.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the early 2000s, the introduction of imatinib led to impressive improvement of progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). |

Nowadays, clinical outcomes provided by a real-life database exhibit a further improvement in PFS and OS. |

This updated effectiveness of imatinib in advanced GIST is of a great importance for researchers and clinicians. |

1 Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) represent the most common mesenchymal neoplasm of the gastrointestinal tract, affecting 17 patients per million per year [1]. Most primary GISTs are found in the stomach and the small intestine, while the remaining minority is located at other sites of the gastrointestinal tract (e.g. esophagus, colon, and rectum). The majority of cases present with localized disease, however about 15% of patients have metastatic disease at presentation [2]. Furthermore, 5 years after complete surgical removal of GIST, 30% of patients will have recurrence or metastases [3].

The introduction of imatinib, a tyrosine-kinase inhibitor with activity against BCR-ABL, KIT, and PDGFRA receptors, led to greatly improved prognosis of patients with advanced GIST. In early 2000s, two phase III trials [4, 5], including the 62005 trial conducted by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), demonstrated the efficacy of imatinib in the treatment of unresectable and metastatic GIST [4]. Since then, imatinib became the indisputable first-line treatment in metastasized and unresectable GIST. With a median follow-up of over 10 years, long-term results demonstrated a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 1.7–2.0 years in patients receiving imatinib, with an estimated PFS at 10 years of 9.2–9.5% [6].

Now, almost 2 decades after the introduction of imatinib, it is of interest for patients, clinicians, and researchers to know the current outcomes of imatinib treatment. In other soft tissue sarcoma’s, it has been reported that outcomes can improve a.o. due to better supportive care [7, 8]. To explore this in GIST, we compared the clinical outcomes in a large and recent patient cohort with clinical outcomes of patient populations in early phase III trials.

2 Methods

2.1 Patients and Study Design

Patients with histologically proven GIST diagnosed between January 2009 and June 2021 were included in this retrospective, multicenter study. The source of the data was the prospective Dutch GIST Registry (DGR), a real-life database containing the clinical data of all GIST patients treated in five GIST specialized centers in The Netherlands. These centers include Antoni van Leeuwenhoek—Netherlands Cancer Institute, Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC), Erasmus MC, Radboudumc, and UMC Groningen. The inclusion criteria were age 18 years or older and metastasized or unresectable GIST treated with first-line imatinib in a palliative setting. Patients were excluded in case of missing response evaluation (not performed or not recorded). The local Medical Ethics Review Committee of LUMC confirmed that the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act did not apply for this study (registration no. G19.122).

2.2 Variables of Interest

Demographic data and clinicopathological features, including localization, tumor size, stage at diagnosis, mitotic count, and mutational status, were collected. Mitotic count was specified as the number of mitotic figures per 50 high-power fields (HPFs), equivalent to 5 mm2.

2.3 Outcomes

The response evaluation was assessed according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 [9] by local investigators. Objective response rate was defined as partial or complete response. PFS was specified as primary outcome, and the secondary outcomes were overall survival (OS) and objective response rate (ORR).

Response evaluation was performed by a standardized schedule, formulated by the Dutch GIST consortium in the standard-of-care guidelines for the treatment of GIST, in accordance with international guidelines [10]. A computed tomography (CT) scan was performed every 3 months. If the patient had symptoms or complaints that might be caused by progression of GIST, the CT scan was performed earlier.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

The duration of follow-up was calculated from date of the start of first-line palliative imatinib to date of last follow-up or date of death. PFS was determined from date of the start of first-line palliative imatinib to date of progression or death caused by GIST. To estimate survival, the Kaplan–Meier method was performed and the groups were compared using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to analyze prognostic factor(s). Potential prognostic factors that were included in a multivariable model were sex, age, performance status, location of primary GIST, mutational status, and sum of the target lesion. IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform the statistical analysis. A p-value < 0.05 was labeled as significant.

3 Results

Overall, 435 patients with advanced GIST registered in the DGR were treated with imatinib as first-line palliative treatment. Of these patients, 420 had recorded response evaluation and could be included in the analysis (Fig. 1). Fifteen patients (3.4%) were lost to follow-up and were not included in the analysis. Demographic and clinical features are listed in Table 1. The starting dose of imatinib was 400 mg daily, except for patients with a KIT-exon 9 mutation who were treated with 800 mg daily. Dose reduction (due to intolerance) was observed in 59 (14.0%) patients. Six patients underwent metastasectomy (liver, n = 2; peritoneal, n = 4) in addition to systemic treatment. In the majority of patients (n = 328, 78.1%), the first systemic treatment received was palliative imatinib, while the remainder of the patients (n = 92, 21.9%) had a history of treatment with (neo)adjuvant imatinib.

Flowchart of patients treated with palliative imatinib in the Dutch GIST Registry. aReasons no palliative therapy in patients: resection of primary tumor and metastasis, patient’s performance score, death due to progressive GIST before initiation of palliative therapy and patient’s decision. b15 of 435 patient were lost to follow up and therefore were not included in the analysis. GIST gastrointestinal stromal tumor

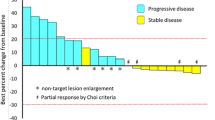

The median follow-up duration was 35.0 months (range 2.0–136.0). Treatment of first-line imatinib resulted in complete or partial response as best response in 238/420 patients: ORR 56.7% (Table 2). During the follow-up, 217 patients (51.2%) eventually showed progression of disease. The median PFS in our cohort was 33.0 months (95% CI 28.4–37.6) (Fig. 2).

After treatment with imatinib, 180 patients were treated with sunitinib, with an ORR of 19%. In 82 patients receiving third-line therapy with regorafenib, an ORR of 14% was observed.

Exploring the survival data of the DGR revealed that 159/420 (37.9%) patients died during the follow-up. The causes of death were progression of GIST in 132 patients, other malignancies (rectal cancer, lung cancer, metastatic melanoma, leukemia, and adenocarcinoma of the stomach) in six patients, and non-malignant diseases (cardiovascular diseases, sepsis, hepatic failure) in 10 patients. An unspecified cause of death was reported in 9 patients. A median OS of 68.0 months (95% CI 56.1–80.0) was observed in patients with first-line imatinib, and the OS estimates at 1 and 2 years were 94% and 84%, respectively (Fig. 3).

Patients with a KIT-exon 11 mutation had a median PFS of 38.0 months (95% CI 30.0–46.0), while a median PFS of 25 months (95% CI 7.4–42.6) was observed in patients having a KIT-exon 9 mutation (p = 0.034). OS analysis showed the same trend; patients with a KIT-exon 11 had a longer OS (73.0 months, 95% CI 57.1–88.9) compared with KIT-exon 9 patients (57 months, 95% CI 48.0–66.0; p = 0.042). The Kaplan–Meier curves for PFS and OS for both KIT-exon 11 and KIT-exon 9 are shown in Figs. 4 and 5.

Studying potential prognostic variables for PFS using Cox regression multivariable analysis (Table 3) showed that sex, age, performance status, location of the primary GIST, and sum of target lesions were not significant prognostic factors. Although just not significant, patients with wild-type KIT/PDGFGR/SDH/BRAF GIST had shorter PFS.

4 Discussion

There is no doubt that imatinib revolutionarily improved the prognosis of GIST patients after confirmation of its efficacy in clinical trials. In a US/Finland phase II trial [11] with a median follow-up duration of 63 months, patients taking imatinib (400 or 800 mg) had an overall median time to progression of 24 months, with a median OS of 57 months. The phase III S0033 trial [5] demonstrated a median PFS of 18 months and median OS of 55 months in patients receiving imatinib 400 mg/day. In EORTC 62055, imatinib 400 mg/day led to an estimated median PFS of 19.5 months.

In the 62005 EORTC phase III trial [4], having a median follow-up duration of 760 days (25.3 months), 473 patients received 400 mg once daily and 473 patients were treated with high-dose imatinib of 800 mg (400 mg twice daily). In patients who were allocated to a daily dose of 400 mg, the proportion of patients with a complete response (n = 24) or partial response as best response (n = 213) was 52.9%. Progression of disease occurred in 263 patients (56%) assigned to imatinib 400 mg and 235 patients (50%) treated with imatinib 800 mg. In the published results of the 62005 trial, the exact duration of PFS was not mentioned in the article; however, when assessing the provided Kaplan–Meier curves, a PFS of 19.5 months can be estimated for patients treated with imatinib 400 mg once daily [4].

In our study, we observed a considerably longer PFS (33 months) than in EORTC 62005 and the other two trials, which were the trials resulting in approval of imatinib 400 mg/day as first-line treatment of advanced GIST and marked the beginning of the era of imatinib in GIST. Furthermore, a higher proportion of patients in the DGR had partial or complete response as best response compared with the 62005 and S0033 trials (Table 4). While median OS in the EORTC 62005 trial was not reached at the time of the published article in 2004, long-term results [6] reported an OS of 3.9 years (46.8 months) among patients treated with imatinib 400 mg. In our cohort, the median OS of 5.7 years (68.0 months) is markedly longer than the introduction time of imatinib in the early 2000s.

A major reason for the superiority of clinical outcomes in our study compared with the EORTC trial and other clinical trials is probably patient selection. Before the introduction of imatinib, no effective treatment was available for advanced GIST (GIST is unresponsive to conventional chemotherapy) [12] and therefore patients participating in the early phase III trials (e.g. EORTC 62005) were mainly those with metastatic GIST who had multiple voluminous lesions. It is very likely that these patients had poorer prognosis than patients treated nowadays (e.g. patients in the DGR), as we know from previously published data that a high tumor burden is a negative prognostic factor in metastatic GIST [13, 14]. Due to advancements in recognizing and diagnosing GIST and timely starting of imatinib, patients are treated when tumor burden is lower. Furthermore, acquired experience in managing the adverse events of imatinib, and the availability of second-, third- and fourth-line therapy, have led to improved prognosis of patients with advanced GIST since the initial phase of the introduction of imatinib.

Better outcomes of treatment with established tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs; the ‘control arm’) for GIST have been reported in several recent clinical trials compared with older data from registration trials. For example, in the Intrigue trial comparing the efficacy of ripretinib (new TKI) with sunitinib (established second-line) as second-line therapy of advanced GIST, patients treated with sunitinib had a median PFS of 8.3 months [15], which is longer than the observed PFS in the registration trial (PFS of 5.6 months) [16]. The same trend applies for the Voyager trial, in which avapritinib was compared with regorafenib in GIST patients who did not respond to prior treatment with imatinib and sunitinib. Patients treated with regorafenib showed a median PFS of 5.6 months as third-line therapy in advanced GIST [17], while in the registration trial, a median PFS of 4.8 months was observed [18].

In the current study, nearly two decades after the introduction of imatinib, we present an update on the outcomes of treatment with imatinib in patients with unresectable and metastasized GIST. The data were retrieved from a real-life database, including clinical details of GIST patients treated in five sarcoma specialized centers in The Netherlands. The results of this study are a fair representation of the outcomes of treatment of GIST patients in a real-world setting. Therefore, these outcomes could serve as an updated reference model when outcomes of (new) agents are compared with imatinib.

The limitations of this study were the retrospective study design and the absence of response status in a proportion (3.4%) of patients, which may have biased the results. Nevertheless, our study contains detailed information on clinical features and outcomes of a relatively large cohort of GIST patients with advanced disease.

5 Conclusion

This study presents an update of the efficacy of imatinib in the treatment of advanced GIST, and demonstrates that clinical outcomes of first-line imatinib are improved compared with the beginning era of imatinib in GIST. Furthermore, these results represent outcomes in real-world clinical practice and can serve as a reference for what can be expected from imatinib in the first-line setting in advanced GIST.

References

Verschoor AJ, Bovee J, Overbeek LIH, Hogendoorn PCW, Gelderblom H. The incidence, mutational status, risk classification and referral pattern of gastro-intestinal stromal tumours in the Netherlands: a nationwide pathology registry (PALGA) study. Virchows Arch. 2018;472(2):221–9.

Nilsson B, Bumming P, Meis-Kindblom JM, Oden A, Dortok A, Gustavsson B, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era—a population-based study in Western Sweden. Cancer. 2005;103(4):821–9.

Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Riihimaki J, Nishida T, Steigen SE, Brabec P, et al. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):265–74.

Verweij J, Casali PG, Zalcberg J, LeCesne A, Reichardt P, Blay JY, et al. Progression-free survival in gastrointestinal stromal tumours with high-dose imatinib: randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9440):1127–34.

Blanke CD, Rankin C, Demetri GD, Ryan CW, von Mehren M, Benjamin RS, et al. Phase III randomized, intergroup trial assessing imatinib mesylate at two dose levels in patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing the kit receptor tyrosine kinase: S0033. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):626–32.

Casali PG, Zalcberg J, Le Cesne A, Reichardt P, Blay JY, Lindner LH, et al. Ten-year progression-free and overall survival in patients with unresectable or metastatic GI stromal tumors: long-term analysis of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Italian Sarcoma Group, and Australasian Gastrointestinal Trials Group Intergroup Phase III Randomized Trial on imatinib at two dose levels. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15):1713–20.

Tap WD, Papai Z, Van Tine BA, Attia S, Ganjoo KN, Jones RL, et al. Doxorubicin plus evofosfamide versus doxorubicin alone in locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (TH CR-406/SARC021): an international, multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(8):1089–103.

Tap WD, Wagner AJ, Schoffski P, Martin-Broto J, Krarup-Hansen A, Ganjoo KN, et al. Effect of doxorubicin plus olaratumab vs doxorubicin plus placebo on survival in patients with advanced soft tissue sarcomas: the ANNOUNCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1266–76.

Schwartz LH, Litiere S, de Vries E, Ford R, Gwyther S, Mandrekar S, et al. RECIST 1.1-Update and clarification: from the RECIST committee. Eur J Cancer. 2016;62:132–7.

Casali PG, Blay JY, Abecassis N, Bajpai J, Bauer S, Biagini R, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2022;33(1):20–33.

Blanke CD, Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Heinrich MC, Eisenberg B, Fletcher JA, et al. Long-term results from a randomized phase II trial of standard- versus higher-dose imatinib mesylate for patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing KIT. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):620–5.

DeMatteo RP, Lewis JJ, Leung D, Mudan SS, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Two hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recurrence patterns and prognostic factors for survival. Ann Surg. 2000;231(1):51–8.

Van Glabbeke M, Verweij J, Casali PG, Le Cesne A, Hohenberger P, Ray-Coquard I, et al. Initial and late resistance to imatinib in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors are predicted by different prognostic factors: a European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Italian Sarcoma Group-Australasian Gastrointestinal Trials Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5795–804.

Bauer S, Rutkowski P, Hohenberger P, Miceli R, Fumagalli E, Siedlecki JA, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with GIST undergoing metastasectomy in the era of imatinib—analysis of prognostic factors (EORTC-STBSG collaborative study). Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(4):412–9.

Heinrich MC, Jones RL, Gelderblom H, George S, Schöffski P, Mehren MV, et al. INTRIGUE: a phase III, randomized, open-label study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ripretinib versus sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor previously treated with imatinib. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(36 Suppl): 359881.

Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, Blackstein ME, Shah MH, Verweij J, et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9544):1329–38.

Kang Y-K, George S, Jones RL, Rutkowski P, Shen L, Mir O, et al. Avapritinib versus regorafenib in locally advanced unresectable or metastatic GI stromal tumor: a randomized, open-label phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(28):3128–39.

Demetri GD, Reichardt P, Kang YK, Blay JY, Rutkowski P, Gelderblom H, et al. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (GRID): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9863):295–302.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No external funding was used in the analysis and preparation of this manuscript. An unrestricted research grant for the DGR to NKI was received from Novartis (3017/13), Pfizer (WI189378), Bayer (2014-MED-12005), and Deciphera (4EE9EEC-7F19-484D-86A4-646CFE0950A5). These funding sources did not have any involvement in conducting this research.

Conflict of Interest

Mahmoud Mohammadi, Nikki S. IJzerman, Dide den Hollander, Roos F. Bleckman, Astrid W. Oosten, Ingrid M.E. Desar, An K. L. Reyners, Neeltje Steeghs and Hans Gelderblom declare they have no conflicts of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this manuscript.

Ethics Approval

The local Medical Ethics Review Committee of LUMC confirmed that the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act did not apply for this study (registration no. G19.122).

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Mahmoud Mohammadi: Conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Nikki S. Ijzerman: Investigation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. Dide den Hollander: Investigation, writing—review and editing. Roos F. Bleckman: Investigation, writing—review and editing. Astrid W. Oosten: Writing—review and editing. Ingrid M.E. Desar: Writing—review and editing. An K. L. Reyners: Writing—review and editing. Neeltje Steeghs: Methodology, writing—review and editing. Hans Gelderblom: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohammadi, M., IJzerman, N.S., Hollander, D.d. et al. Improved Efficacy of First-Line Imatinib in Advanced Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GIST): The Dutch GIST Registry Data. Targ Oncol 18, 415–423 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-023-00960-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-023-00960-y