Abstract

The main aim of this paper is to conceptualise and empirically estimate subjective well-being capability. The empirical demonstration of the conceptual framework is applied in a selection of European countries: Poland and its leading emigration destinations the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands, Ireland, France and Italy. The paper advances the measure of subjective well-being capability (SWC) as the integration of the subjective well-being measure with the capability approach in a unified measurement framework. Following the development of a conceptual model, the theoretical framework is operationalized empirically to quantify measures of SWC across the selected countries using a Multiple Indicators and Multiple Causes Model. Data from the European Quality of Life Survey is employed. A comparative analysis compares the SWC measures across countries as well as comparing SWC with conventional well-being measures such as overall happiness and GDP per capita. The results of the study reveal a significant correlation between the SWC based on a general model for all countries, overall happiness, and GDP per capita. However, it also suggests that country-specific SWCs, calculated from tailored models, could substantially deviate from traditional well-being measurements. This attribute suggests that SWC could be a practical tool for assessing individual contexts, as reflected in the tailored models, even though it might not serve as the optimal instrument for country ranking (via the general MIMIC model).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The 'happiness approach' and the ‘capability approach' are two well-established methodologies for measuring well-being that have been portrayed as alternatives to the standard welfare economic approach. While the study of subjective well-being (SWB), focused on studying quality of life as an end outcome, and expressed in ‘happiness economics’ studies, such as Easterlin’s (1974) pioneering study exploring psychological happiness and income developments, emphasises an analysis of subjects' feelings of happiness, sadness or life satisfaction, Amartya Sen's (1979, 2005) capability approach (CA) draws attention to the objective basis for the realisation of well-being, such as the possibility of living a normal length of life, being able to move around freely or having shelter. The main aim of this paper is to integrate the SWB notion with the CA into a unified measuring framework. This paper contributes to the conceptual and empirical effort towards such integration in particular by (a) exploring the notion of subjective well-being capability (SWC) coined by Martin Binder (2014) and most recently applied by Yei-Whei Lin et al (2023) and (b) comparing SWC with conventional well-being measures such as overall happiness and GDP per capita in selected European countries.

Following the SWC conceptualisation, we conduct an empirical analysis that involves a comparative examination of SWC in Poland and its main emigration destinations, such as the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands, Ireland, France, and Italy.Footnote 1 While the criterion of Polish leading emigration destinations is used to identify a group of countries for comparison, and we do not intend to investigate the particular context of migration, the present research can nevertheless offer a valuable starting point to further research on migrants’ choice and migrational motivations. There is a growing body of research that focuses on the happiness and life satisfaction of immigrants, individuals in their country of origin, and host citizens (Bartram, 2011; Hendriks & Bartram, 2019; Kogan et al., 2018; Voicu & Vasile, 2014). Developing the concept and measure of SWC, which emphasises the agency aspects of well-being, can hold great value in evaluating people's decisions to emigrate and their relative position in relation to their compatriots and the citizens of the host country. Although for the present article the empirical study is for descriptive purposes, and such an application goes beyond the scope of this analysis, the aim would be to analyse whether differences in SWC can serve as motivation for migration movements.

We propose measuring individual SWC as a latent variable. To calculate SWC, a Multiple Indicators and Multiple Causes Model (MIMIC) is employed. MIMIC is a special case of the general structural equation model (SEM) which consists of a structural model and a measurement model (Jöreskog & Goldberger, 1975). The former describes the causal link among the latent variable and its observed (exogenous) determinants while the latter shows how the latent variable is defined by the observed indicators (we understand these observed indicators to be functionings, in the language of the CA). In modelling SWC empirically, we draw on the methodology adopted by Zwierzchowski and Panek (2020), who utilise the MIMIC model to evaluate the SWB of Polish citizens. Building on this work we, firstly, develop a clear conceptualization that distinguishes SWC from SWB. Secondly, we use a new dataset, namely the European Quality of Life Survey (EQLS), which includes relevant variables regarding overall happiness. Thirdly, our analysis involves a cross-country comparative approach instead of focusing on a single-country analysis. We also highlight the specific aims of the present paper. In our analysis, we aim to explicitly integrate SWB with CA and assess the applicability of a new index of SWC. This issue is somewhat timely as other researchers are also engaging in developing SWC as an approach for evaluating living conditions among different groups of people (Lin et al., 2023).

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section "Bridging Subjective Well-being and the Capability Approach: A Foundation for Subjective Well-being Capability" describes SWB and the CA as the theoretical foundations for SWC. Section "Conceptual Model of Subjective Well-Being Capability Measurement" examines how individual well-being capability (SWC) may be empirically measured within one framework. The empirical analysis, which comprises data descriptions, the MIMIC model specification and the SWC estimates, is presented in Section "Empirical Analysis". The results are discussed in Section "Discussion". Final conclusive remarks close the paper.

Bridging Subjective Well-being and the Capability Approach: A Foundation for Subjective Well-being Capability

A burgeoning set of well-being measures and indices reflect a growing trend and appetite for the broadening of the informational space to assess individual ‘progress’ and well-being (Hoekstra, 2019). The two most significant responses to date to the critiques of traditional income-based well-being measures have been the subjective approach to well-being (SWB) and the CA. The SWB literature largely refers to psychological states and how a person experiences particular moments or how she evaluates her life as a whole or over a period of time as measured expressions of well-being. The most common categorical distinctions in SWB are evaluative, eudaimonic and experienced well-being (Dolan et al., 2011; Layard & De Neve, 2023). The CA, on the other hand, provides a normative framework for assessing individual opportunity to achieve certain objective goods for measuring well-being (Sen, 1979, 1992). Both approaches shift the focus of well-being measurement from means-based (resourcist approach) to ends-based analysis (well-being), however, taken separately are both subject to critiques of offering limited information on individual well-being without due regard for the informational set of the other (Comim, 2005). SWB is prone to problems of hedonic adaptation, whereby it is observed that individuals may understate their level of deprivation in a number of areas because of their personal disposition or because of adaptation and acceptance of life’s long-term circumstances. The measures do not account for an individual’s objective circumstances, such as a being in a position of long-term poverty, even if they report being happy or satisfied. Yet, notions of happiness captured by SWB are considered important to an overall assessment of well-being which an objective account, as the CA expresses, can be prone to omitting.

These two approaches are most frequently treated in well-being measurement literature as exclusive to one another. In this regard, scholars commonly take either a CA to well-being measurement or a SWB approach, with limited work on integration of the two. This, however, is changing (Binder, 2014; Lin et al., 2023). The difficulty comes about from an implicit emphasis on irreconcilable differences in the philosophical premises, such as attention to individual agency and autonomy, intrinsic value of choice, or on the methodological objective or subjective assessment of welfare, on which each approach is grounded. While the SWB approach draws on psychological insights to define the nature of human well-being to be measured and is often grounded in a utilitarian normative framework, the CA can be traced more closely to an Aristotelian concept of eudaimonia (human flourishing and objective notions of the standard of living) to assess individual welfare objectively and in part externally to the person’s own assessment.

A growing number of recent studies have been taken up to draw links between the two approaches and the areas of compatibility between them (Binder, 2014; Comim, 2005; van Hoorn et al., 2010). These few studies have been motivated by the observation that the two approaches are fundamentally linked by several meaningful synergies in the context of individual welfare evaluation (Binder, 2014; Comim, 2005).

Following these links, there are three ways in the which the literature has bridged these two approaches so far:

-

1.

The integration of CA into SWB framework scenario: analysis is undertaken of the extent to which capabilities influence or determine SWB (Graham & Nikolova, 2015; Muffels & Headey, 2013; Veenhoven, 2010).

-

2.

The integration of SWB into the CA framework scenario: SWB or “being happy” is analysed as a relevant dimension or capability for individual welfare among other relevant capabilities (Robeyns, 2017; Zwierzchowski & Panek, 2020).

-

3.

The bridging scenario: the question of how either approach can be enriched by the other (Lin et al., 2023; Kwarciński and Ulman, 2018; Binder, 2014; Kotan, 2010; Comim, 2005).

This paper aims to situate itself in the third strand of literature, and explore and empirically operationalise precisely the concept of SWC. Of particular significance to our present study is the finding that substantial shortcomings of the SWB approach “can be overcome by focusing welfare assessments on ‘subjective well-being capabilities’, that is, focusing on the substantive opportunities of individuals to pursue and achieve happiness” (Binder, 2014). The concept of SWC to be developed and operationalised in this paper moves away from depending on psychological profile alone of SWB measures. At the same time, the domains of happiness that these measures focus on (evaluative, eudaimonic and experienced) are analysed from the perspective of the opportunity that an individual has to achieve them. That is, SWC seeks to map the potential individual opportunities to achieve happiness. Conversion factors, a notion adopted from the CA, further allow for an analysis of the factors that determine the person’s individual opportunities to achieve happiness in the SWB domain. In this way, the SWC concept provides a broader informational space for individual well-being analysis.

There are several reasons to be interested in the theoretical notion of SWCs and their measurement. Firstly, in line with Sen’s theoretical stance, the concept of SWC recognises the importance of ‘happiness’ to overall human welfare according to the CA, but acknowledges its partiality and limitation as a sole indicator of individual welfare, (mainly due to the issue of hedonic adaptation). What we would expect to evaluate is a situation where a person may have high SWB (reports a high state of happiness) but low SWC (is objectively materially or otherwise deprived).

Secondly, it brings to light the distinction between Sen’s (1993) well-being freedom and agency freedom. As autonomous agents, individuals use their agency to determine their overall achieved well-being from the genuine alternative freedoms (capabilities) available to them (their capability set), receiving intrinsic value from the choice itself. Agency plays out in individual welfare measurement in two ways, and is related to the intrinsic value he attaches to choice. It implies that value may be found in the utility or disutility regarding the range of choices available to the individual (i.e. the range in choice of functionings in their capability set).

Additionally, though, there is intrinsic value in the individual simply being able to choose. SWB functionings could exist separately from the concept of SWC, but the concept of freedom or gauge of individual opportunity would be missing from the analysis (Binder, 2014). From a Senian perspective, individuals as autonomous agents have their own rankings according to which trade-offs and selections between capabilities that form part of an individual’s capability set are made. SWB functionings may be selected or traded-off according to an individual’s priorities and ranking. With the SWC notion, we suggest that SWB functionings be considered functionings that form part of an individual’s capability set, among other functionings.

Thirdly, the SWC approach allows for the empirical identification of relevant functionings underlying achieved happiness levels, so as not to have to rely on the top-down expert-given opinion of the factors that represent happiness (Lin et al., 2023).

Conceptual Model of Subjective Well-Being Capability Measurement

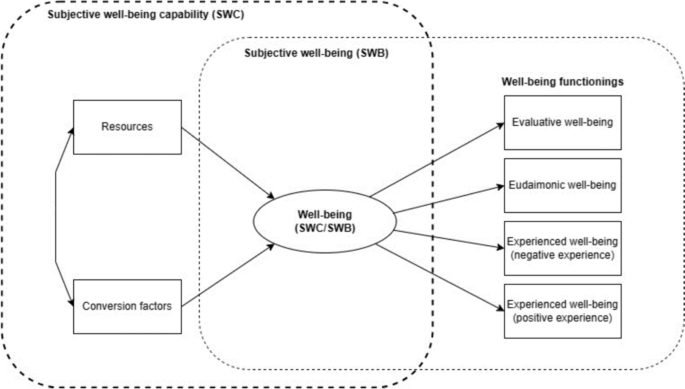

In formulating SWC, we seek to model the opportunities that a person has for happiness, the latter of which (happiness) is directly observable from SWB indicators of happiness. What is not directly observable is the individual opportunity to achieve given happiness levels, which we denote as SWC. From a theoretical perspective, we specify the analytical components of the CA informational space, which includes: resources, conversion factors, functionings, and capabilities. The unobservable element here is SWC. Functionings refer to the various ways individuals experience happiness in their lives. Resources encompass personal assets such as health conditions or educational attainment, while conversion factors include personal, social, and environmental circumstances that influence the way a person can make use of their resources to achieve a desired level of happiness.

The purpose of building a SWC model is to be able to measure SWC – that is, opportunities for happiness in the SWB domain, and study whether there are certain sub-groups of individuals who are more or less disadvantaged in the potential happiness they can achieve, that is, have higher or lower SWC. This would imply that there are certain sub-groups of individuals who have potentially less access to SWB functionings. In the case of our application, individuals’ opportunities are explored at the country-level for a selection of European countries.

For the empirical operationalization of SWC in this study, we adopt a research approach that infers capabilities using latent variable models (Anand et al., 2011; Krishnakumar & Ballon, 2008; Sarr & Ba, 2017; Yeung & Breheny, 2016). The methodology has also recently been employed by Zwierzchowski and Panek (2020), who utilize multiple indicators and multiple causes models (MIMIC) in their study of SWB in Poland. However, in order to address the ambiguity present in their approach – where they interpret the estimated latent variable as both potential SWB (Zwierzchowski & Panek, 2020, 164) and as a composite indicator of SWB (Zwierzchowski & Panek, 2020, 165) – we propose the following operationalization of SWC (Fig. 1).

In the outlined operationalization, we introduce a clear distinction between SWB as a composite index and potential SWB, which we term SWC. The composite index of SWB would be estimated solely from the (SEM) measurement model (confirmatory factor analysis). This index is also distinct from SWB based on a single ‘overall happiness’ variable. The SWC index, on the other hand, is derived from a structural model. By choosing linear predictors from the structural model instead of factor scores in MIMIC, we follow Krishnakumar and Chávez-Juárez (2016), who argue that linear predictors perform better when the indicator variables are highly correlated with each other, which is usually the case in empirical analysis, including our study.

In the measurement model we follow the conventional taxonomy on SWB, dividing the concept into three parts: (1) evaluative, (2) eudaimonic and (3) experienced. Evaluative well-being refers to overall life satisfaction or fulfilment; eudaimonic well-being involves seeing one's life as meaningful and taking purposeful actions; while experienced well-being, also known as hedonic well-being, consists of positive and negative effects experienced by individuals (Layard & De Neve, 2023; National Research Council, 2013). The three-part concept of well-being overlaps with the CA for at least two reasons. First, because the self-reported evaluation of life, the positive or negative feelings experienced, are ways of ‘being’ (and things that can also affect individual ‘doings’)—‘beings’ and ‘doings’ are important ontological categories in Sen’s capability theory, through which welfare opportunity is interpersonally assessed. Second, Sen emphasises the hedonic aspects of well-being in his works, despite rejecting SWB as a primary system for well-being evaluation (Burns, 2022; Sen, 1987, 2008).

While capabilities, and opportunities more broadly, are found to be positively correlated with life satisfaction (Ravazzini & Chávez-Juárez, 2018; Steckermeier, 2021), a possible implication is that some form of individual valuation of opportunity or notions of agency may be implicit in SWB assessments, particularly within evaluative or eudaimonic SWB. However, the SWC measure does not examine the relationship between possessing a specific range of opportunities or having agency, and achieving a given self-assessed level of SWB. Instead, it focuses on the individual’s opportunity to achieve certain SWB functionings. The difference, while conceptually subtle, is central to the present study.

In the structural model we include sets of resources and conversion factors. By resources, we understand any tangible or intangible resources that are at an individual’s disposal and that serve as “inputs” to happiness, that is are related to generating the person’s happiness. These can include such things as education, income or health. The adoption of conversion factors that the CA offers allows for an investigation into whether certain personal, social or environmental characteristics impact upon how and to what extent individuals can differently utilise resources for happiness.

It is worth noting that the distinction between resources and conversion factors in the context of empirical analysis commonly depends on the given functionings or capabilities being analysed, and can be to some degree arbitrary. Conceptually, there is a clear distinction between these two categories. However, in practice, the categories become highly challenging to delineate due to the interplay between resources and conversion factors. In different circumstances, resources can function as conversion factors or influence other resources and conversion factors. For instance, health can serve as a personal asset or as a conversion factor which impacts the extent to which someone can utilise financial resources. This provides a theoretical justification for the high degree of correlation observed between variables describing resources and conversion factors.

To our knowledge there is only one similar theoretical attempt to integrate SWB with a capability-based approach by focusing on SWC (Binder, 2014), and one recent empirical application (Lin et al., 2023). According to Binder (2014), policymakers should take into account not only SWB but also happiness-relevant functionings, which are the ways of being and doing which make people happy. He cites employment, having an income, having good health, having friends, etc. as examples of such functionings (Binder, 2014). Following Binder’s (2014) approach, we would first have to identify happiness-relevant functionings by running linear regression of the various functionings on the happiness index. We could then construct a MIMIC model in which we would place within the SWC indicators the most statistically significant happiness-relevant functionings. This approach would also require rethinking which elements make up the set of resources and conversion factors. Selecting relevant resources, and happiness-relevant functionings would be vulnerable to criticism for a paternalistic approach. We adopt a more direct approach, similar to Lin et al. (2023), where instead of happiness-relevant functionings, we include SWB functionings, such as feeling happy, not feeling of sadness, enjoyment, being full of life, doing worthwhile things, and so on, into the MIMIC model. What we share with Binder is a general view of SWC, as “the substantive opportunities an individual enjoys to pursue and achieve happiness.”

The SWC derived from the MIMIC structural model is an assessment of an individual's capability to achieve SWB, taking into account not only SWB functionings but also available resources and conversion factors in its calculation. This approach aligns with the theoretical foundations that define capabilities as the real freedoms to perform particular functionings, which depend on resources and specific conversion factors. It also adheres to empirical conventions that apply statistical techniques, such as the MIMIC model, to calculate, based on observed functionings, a latent variable interpreted as an unobserved capability.

Empirical Analysis

Data

The study utilises the European Quality of Life Survey (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2018), which allows us to present distinct findings compared to those of Zwierzchowski and Panek (2020). This dataset offers distinct advantages as it includes the ‘overall happiness’ variable, which is not present in EU-SILC. Incorporating this variable into our analysis serves as a valuable reference point for measuring subjective well-being capability (SWC) outcomes. This article uses data from the last wave of EQLS 2016 for selected EU countries: Poland, United Kingdom, Germany, France, Ireland, Italy and the Netherlands. The assumption of the survey is that the sample size for a given country cannot be less than 1000 units. Thus, the smallest sample size was taken for Poland (1009) and the largest for Italy (2007).

As with any empirical study that involves surveying individuals, missing responses occur, resulting in missing data in the database. Deleting all records in which at least one of the examined variables was missing would lead to a significant reduction in the number of observations in the sample for a given country. It was therefore decided to fill in the mentioned gaps for selected potential variables under analysis. In the first phase, we chose the variables for the study from a large list of variables accessible in the EQLS 2016 dataset. Then, the missing data were filled in using a predictive mean matching algorithm (R package MICE).

The set of variables consists of three subsets: SWB functionings, conversion factors and resources. As mentioned, SWB is composed of three elements: evaluative well-being, eudaimonic well-being and experienced well-being. To measure evaluative well-being we use a life satisfaction ten-point ordinal scale. Eudaimonic well-being is captured by the statement “I generally feel that what I do in life is worthwhile” and measured on a six-point ordinal scale. In the case of experienced well-being, we use three statements to reflect negative affections: “I have felt particularly tense”, “I have felt lonely”, “I have felt downhearted and depressed” and three statements to reflect positive ones: “I have felt cheerful and in good spirits'', “I have felt calm and relaxed”, and “I have felt active and vigorous”. Responses are measured on a six-point ordinal scale.

It is important to note that resources and conversion factors are depicted through variables that serve as stimulants to well-being. This is applicable to variables where the order of states they represent can be distinctly aligned within the context of well-being. For example, the binary variable ‘absence of unemployment’ is coded so that the value zero represents a person who is unemployed, and one indicates a person who is not experiencing unemployment. Detailed information on all variables can be found in the appendix, specifically in Tables 5 and 6.

Furthermore, we employ the variables ‘overall happiness’ and ‘GDP per capita’ for comparison with the SWC, which is calculated from the estimated model. The ‘overall happiness’ variable is distinct from the other related ‘happiness’ variables in the model and is determined based on responses to the question: “Taking all things together on a scale of 1 to 10, how happy would you say you are?” Additionally, the GDP per capita in 2016 is measured using purchasing power parity (current international $) and comes from the World Bank dataset.

Estimation of the MIMIC Models and SWC

Using the prepared data for seven countries, we estimate the Multiple Indicator and Multiple Causes Model (MIMIC). MIMIC is a special case of Structural Equation Models (SEM)Footnote 2. A feature of this type of model is that it contains two parts: measurement and structural. The measurement part defines the latent (unobservable) dependent variable, while the structural part contains exogenous observable variables, i.e. factors that potentially vary the level of the above-mentioned unobservable dependent variable measured by the measurement part of the model.

Formally, MIMIC can be written as:

where:

\(y\) – vector of observable endogenous variables,

\(\Lambda\) – vector of factor loadings of endogenous variables,

\(f\) – a latent endogenous variable (composite indicator of SWC),

\(B\) – vector of coefficients of latent variable to observable exogenous variables x,

\(x\) – vector of observable exogenous structural variables,

\(\varepsilon,\psi\) – vectors of error terms.

The estimation of model parameters can be performed by different methods. This paper uses maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) implemented in the IBM AMOS package. The MIMIC models are estimated using the weighting system contained in the EQLS dataset.

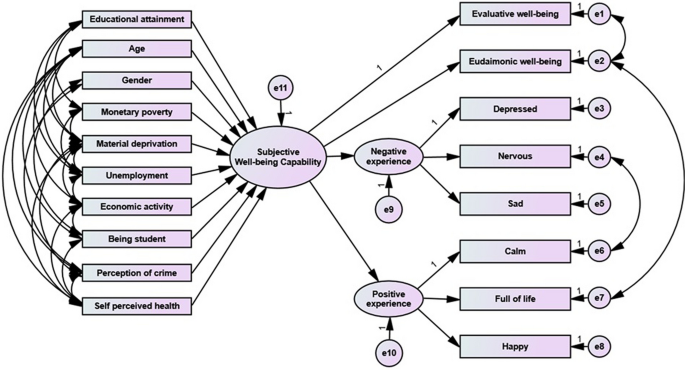

An important step in the construction of a MIMIC model is to define its measurement part. This part of the model describes the relationship between the unobservable (latent) variable and the observable variables used to measure it. Task-wise, the measurement model should be defined before the structural part of the MIMIC model is introduced. The SWB functionings depicted in Fig. 1 and Table 5 inform the configuration of the measurement model. This model's framework is shaped by theoretical underpinnings that posit SWB as comprising evaluative well-being, eudaimonic well-being, and experienced well-being. The latter encompasses both positive and negative life experiences. Figure 2 presents an example of a MIMIC model in the context of Poland. The results of the estimation of the parameters of the measurement model for all countries studied are presented in Tables 2 and 4. They confirm the significant importance of the individual variables (functionings) in determining the latent variable: SWC.

Once the form of the measurement model is established, the structural part of the MIMIC model is constructed by selecting the exogenous variables, which are the resources and conversion factors (see Table 6). In the course of estimating the full MIMIC model, some of the exogenous variables prove to be statistically insignificant, with the set of variables varying from country to country. The outcomes of the structural and measurement model estimations are also detailed in terms of standardised assessments in Tables 3 and 4.

The model quality metrics employed (R-square and RMSEA) suggest an adequate fit of the model to the empirical data when using the individual-level dataset. In the analysis of metric invariance for measurement model, comparing the comprehensive model (MIMIC GEN) to individual country models reveals that for Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, the disparity in chi-square values (between the country-specific model and the general model) suggests a rejection of the metric invariance hypothesis. Nevertheless, the incremental fit indices (Normed fit index—NFI, Incremental fit index—IFI, Relative fit index—RFI, Tucker-Lewis index—TLI) reveal only a nominal variation between these models. Moreover, the fit metrics for models without constraints and those with subsequent restrictions differ marginally, which could imply that metric invariance is maintained despite the hypothesis being rejected. The rejection of the metric invariance hypothesis may be attributable to the relatively large sample sizes, which could lead to the nullification of the hypothesis even when the discrepancies between the models under comparison are minor.

To assess the stability of outcomes, we estimated the results under the different assumption of no correlations among variables in the measurement model. The deviations from values obtained with the initial methodology were minimal. However, it is important to note that the model quality indicators showed a slight decrease in performance compared to the original models.

The MIMIC model enables the estimation of individual SWC values. These values are derived from the structural model estimated for each country individually as well as for all countries collectively (referred to as MIMIC GEN). They are then normalised using the formula:

where:

\({f}_{ij}-\) estimated individual SWC value for i household and j country (or generally for all countries).

Two approaches are used: within-state normalisation and across-states normalisation (the results of the SWC estimation are combined for all states and normalised based on these). The first approach follows the relative way of identifying poverty, where the national median income is determined and the equivalent household income is related to the corresponding share of this median within a country. In contrast, the second approach – it seems – more broadly allows for comparisons of welfare levels between countries.

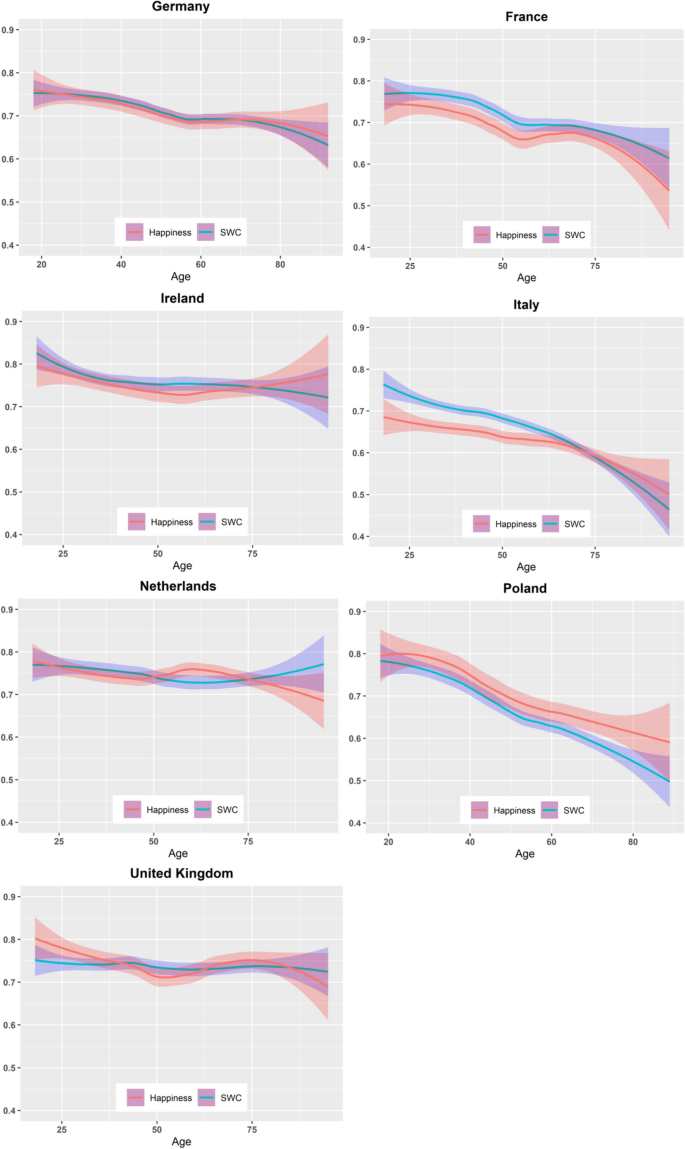

Comparative analysis of the SWC and overall happiness over age in different countries is made by locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) in R-package ggplot2.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Using data from the EQLS, our analysis covers SWC results for seven European countries. When examining SWB indicators, the descriptive statistics reveal that SWB remains relatively consistent among the seven countries, with minor variations. For instance, the range for life satisfaction sits between 6.56 (Italy) and 7.74 (Netherlands), suggesting that there is not a significant variation in life satisfaction among the countries. In general, Ireland appears to have higher levels of positive attributes such as life satisfaction and happiness, whilst maintaining lower levels of negative indicators such as nervousness and sadness. Conversely, Italy exhibits the opposite pattern with increased negative attributes and lower positive ones. Variability in responses differs considerably across countries, indicating differing levels of consensus among the populace concerning SWB. For example, Italy often shows high variability, indicating that responses in this country may be quite diverse. On the other hand, the Netherlands often shows lower variability, implying more consistency in responses.

When considering the determinants of SWC, such as resources and conversion factors, a noticeable disparity between countries becomes apparent. The descriptive statistics indicate distinct patterns based on average income. There are two main groups of countries: (1) the affluent group consisting of the Netherlands, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, with an average equalised monthly income in purchasing power parity exceeding 1500 Euro, and (2) the less affluent group comprising Italy and Poland, with an average income in purchasing power parity per person less than 1300 Euro. Ireland falls in between the two groups, with an income approaching 1400 Euro. We find a partial confirmation of this division of countries by analysing the percentage of the poor, which is the highest in Poland and Italy. Ireland, in this case, is included in the group of wealthy countries with one of the lowest shares of the poor. This situation can be explained by a relatively young population with a large number of people in the household, which reduces the equivalised income and shapes the distribution of this income in such a way that 60% of its median (as the poverty line) generates the lowest poverty rate. Poland belongs to the group of countries with a low level of health quality, along with Italy and Germany, but only Italians have the lowest level of medical needs satisfied, with approximately 60%, while in other countries the percentage is at least around 80.

Regarding gender, samples in all countries are generally balanced, with slightly fewer men than women, typically around 48% men. Ireland also has the youngest average age of respondents compared to other countries (46.2 years), where the average age is around 50 years, excluding Poland with an average age of 47 years. This relatively young Irish population is potentially associated with the level of other characteristics, e.g. household size (average highest), percentage retired (by far the lowest), percentage of students (the highest together with Poland) or perceived health status (most often rated as very good). Among the variables that make up the conversion factors, one that stands out is the risk of crime experience. The highest risk of crime is experienced in the Netherlands, and France, the lowest in Italy. Table 7 presents descriptive statistics for SWB indicators and SWC determinants, along with overall happiness and GDP per capita for each country.

Comparative Analysis of SWC

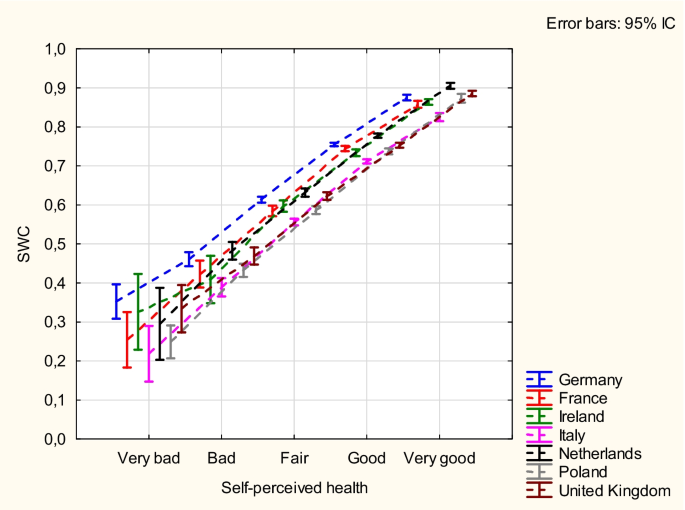

Comparing the countries studied on the basis of separately estimated MIMIC models, we observe correlations between three factors and SWC across all countries. In each case, the lower the level of material deprivation, the lower the perception of crime in the neighbourhood, and the better the self-perceived health the higher the estimated SWC (Table 1). Self-perceived health consistently exhibits the largest effect size relative to other factors across all countries (Table 3). In the case of Poland, our analysis partially confirms the findings of Zwierzchowski and Panek (2020, 167). Similar to their research, the most significant factors influencing SWC in Poland are self-perceived health and absence of material deprivation (Table 3). Furthermore, there are statistically significant factors that are unique to each of the countries analysed. Household equivalent income emerges as a significant factor in Ireland, where higher income is linked to higher SWC. Additionally, not being a student is associated with higher SWC in Poland (Table 1).

The affluent group of countries, comprising the Netherlands, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, share three primary factors that significantly influence SWC: larger household size, unemployment status, and the absence of unmet medical needs. Interestingly, since the average household size in these countries is relatively low, increasing family structures or cohabitation affects SWC. The United Kingdom also indicates an association between lower levels of education and SWC. Retirement status significantly and positively influences SWC in France and the United Kingdom, which might imply a certain level of satisfaction or quality of life linked with retirement in these countries.

Italy and Poland, despite being grouped as less affluent countries, exhibit dissimilar influencing factors. In Italy, living above the monetary poverty line, not perceiving pollution, larger household size, unemployment status, and absence of unmet medical needs are pivotal. It is worth noting that the last three factors mentioned make Italy similar to its more affluent counterparts. Poland, in contrast, experiences the influence of higher education, female gender, unemployment status, low economic activity, and non-student status on SWC. This juxtaposition between Italy and Poland highlights diverse socio-economic conditions and their distinct impacts on SWC.

In Ireland, which falls between more and less affluent countries, retirement status is positively associated with SWC, similarly to France and the United Kingdom. Additionally, the perception of pollution influences SWC in Ireland, similarly to Italy but in the opposite direction. In Ireland, a lack of perception of pollution is linked to an increase in SWC, whereas in Italy, people have a perception of pollution, which negatively affects SWC. Moreover, the results for Ireland indicates that older age is negatively linked to SWC, contrasting with findings from Germany, where older individuals experience higher SWC. This stands in opposition to the typical association of higher SWC in older, retired populations.

In the general model (MIMIC GEN) estimated for all countries combined, almost all variables are statistically significant, with the exception of gender and being a student (Table 1). The factors that exhibit the largest effect sizes, compared to others, include self-perceived health, absence of material deprivation, and perception of crime in the neighbourhood (Table 3). SWC cross-sectional analyses are conducted using the MIMIC GEN model, as it allows us to assess the variability between countries consistently.

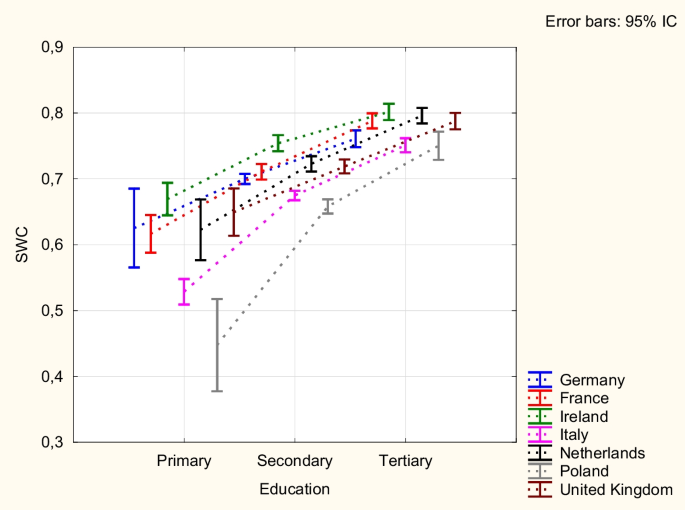

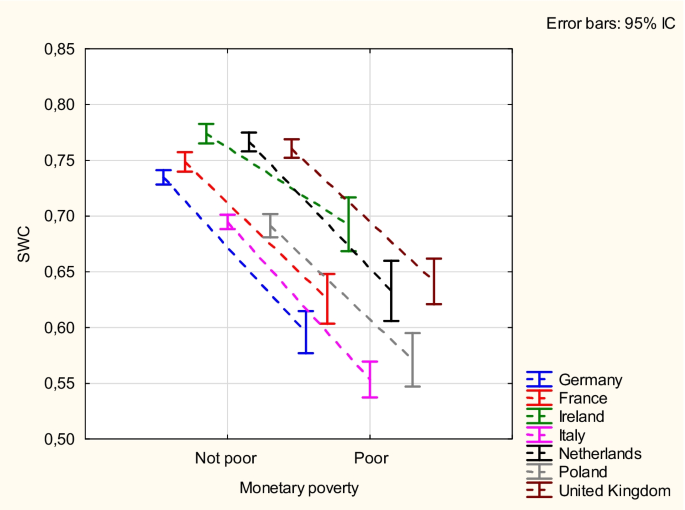

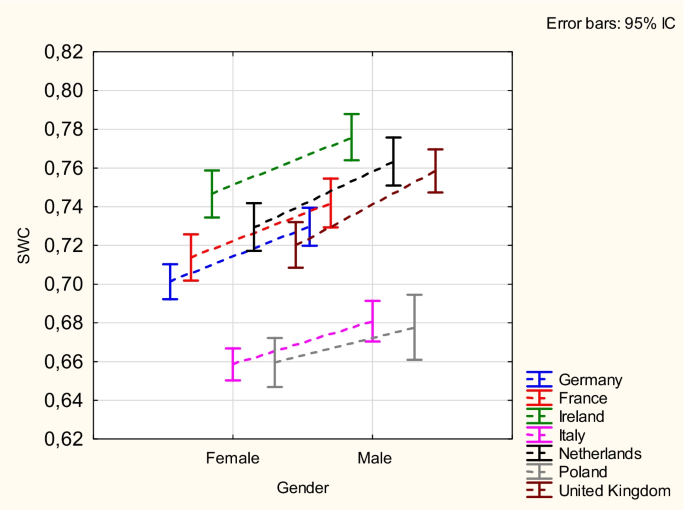

In most cross-sections, the same general pattern is found in all countries. Analysing the SWC from the perspective of respondents' education level, health status, poverty status, and gender we notice similar dependencies in all the countries. In general, the higher the education level of the respondent, the higher the SWC (Fig. 3), the worse the self-perceived health status, the lower the SWC (Fig. 4), and belonging to the highest level of poverty group is associated with lower SWC (Fig. 5). What is more, in all countries, men's SWC appears to be higher than women's, although in the case of Poland and Italy both genders have significantly lower SWC compared to the other countries surveyed (Fig. 6).

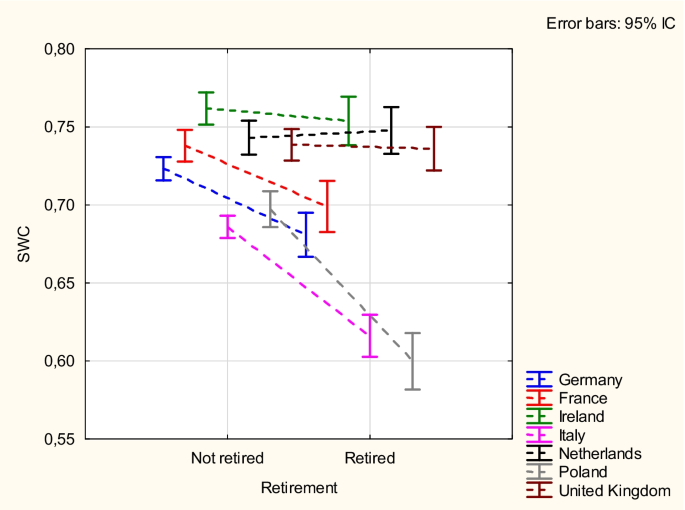

Only when respondents are stratified by being retired are there significant differences between countries with respect to SWC. There is also an apparent division into two groups of countries, those where retirees have higher or equal SWC relative to non-retirees (Netherlands, United Kingdom, Ireland), and those where SWC is lower among retirees (Germany, France, and notably in Poland, Italy) (Fig. 7).

The analysis of SWC variability, as discussed with reference to Figs. 3–7, is further supported by the Welch test. The Welch test, a corrected version of the One-Way ANOVA, identified significant differences (at a significance level of 0.05) across all countries based on respondents' education level, self-perceived health status, poverty, and gender. Regarding gender, a notable exception is Poland, where a difference between genders is not statistically significant. Moreover, significant differences due to retirement status are observed exclusively in Germany, France, Italy, and Poland.

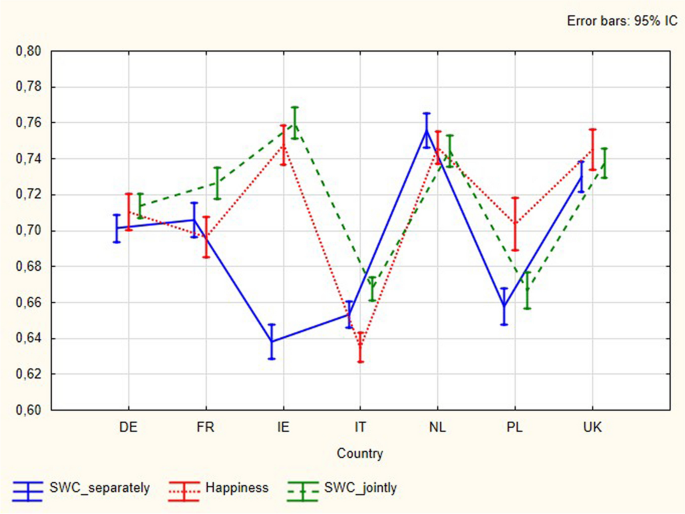

SWC and conventional well-being measures

The relationship between SWC and the conventional well-being measures (overall happiness and GDP per capita) can provide valuable insights into the reliability and applicability of SWC. When examining the mean SWC based on MIMIC GEN, it becomes apparent that there is a strong and significant correlation with both the mean overall happiness and GDP per capita across countries (r = 0.80 and r = 0.81, respectively). However, when considering the mean SWC estimated separately for each country, the correlation with mean overall happiness is notably weaker and insignificant (r = 0.39). Similarly, the correlation between the mean SWC estimated separately for each country and GDP per capita is low and insignificant (r = -0.05).

Considering SWC based on MIMIC GEN and across-states normalised (green line in Fig. 8), only Italy has a similarly low average SWC compared to Poland. Moreover, although the average overall happiness index for Poland is higher than in Italy, the average SWC in both countries is at similar levels. It is also worth noting that the average overall happiness and average SWC in most countries, with the exception of Poland and Italy, are very close (Table 8). Considering SWC based on MIMIC models calculated separately with within-state normalization for the countries (illustrated by the blue line in Fig. 8), it can be observed that Ireland has the lowest value of SWC and exhibits the greatest disparity between the calculated SWC, SWC based on MIMIC GEN, and overall happiness.

Tukey's Range Test (Tukey's HSD) confirmed that for SWC derived from separately calculated MIMIC models, there are no significant differences between Germany and France, Ireland and Italy, Ireland and Poland, as well as Italy and Poland. Regarding Happiness, no significant differences were found between Germany and France, Germany and Poland, France and Poland, Ireland and the Netherlands, Ireland and the United Kingdom, as well as between the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. For SWC based on the MIMIC GEN model estimated for all countries combined, significant differences are absent between Germany and France, France and the Netherlands, France and the United Kingdom, Ireland and the Netherlands, Italy and Poland, as well as between the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

Comparing SWC with overall happiness over the lifetimes of people in each country yields some interesting results (Fig. 9). For most countries, both SWC and overall happiness decrease as respondents’ age increases (Germany, France, Italy, Poland). More importantly, however, is the fact that only in selected countries and only in certain periods of the respondent's life is the SWC index statistically different from the overall happiness index. This is particularly evident in Italy until the age of 60. This suggests that, when taking into account the resources at their disposal and the influence of conversion factors, individuals below 60 years of age have more opportunities to experience happiness than they tend to report in terms of the overall happiness level.

SWC and overall happiness. Note: Differences between overall happiness within-state normalised (dotted line) and SWC estimated separately for each country, within-state normalised (solid line) and SWC estimated for all countries combined (MIMIC GEN), across-states normalised (dashed line). Source: own calculation

Discussion

Integrating the SWB and the CA into a unified framework allows us to conceptualise and measure the real opportunities for achieving SWC among citizens of selected European countries. While these countries' populations exhibit numerous similarities in terms of SWC, such as important factors influencing SWC and similar patterns regarding the relationships between education levels, health status, poverty, gender, place of residence and SWC, which can be attributed to shared socio-economic conditions, there are specific aspects that warrant further exploration.

Firstly, it is noteworthy that looking at the MIMIC GEN model Poland and Italy exhibit the lowest levels of SWC among the investigated countries. Both are found in the less affluent country group. Furthermore, there are distinctive patterns in the relationship between retirement status and SWC in these two countries compared to the others. Italy also experiences a notable discrepancy between overall happiness and SWC (MIMIC GEN) throughout individuals' lifespans. Moreover, Ireland demonstrates a significant gap between SWC based on MIMIC GEN and SWC based on the tailored model, highlighting the need for further examination. Additionally, the strong correlation between SWC based on MIMIC GEN and conventional measures of well-being emphasises the issue of the practical application and utility of such sophisticated models. What follows is a discussion regarding the above four findings.

Poland and Italy display overall lower levels of SWC (MIMIC GEN) for both women and men than the remaining countries in this study (Fig. 6). Both of these countries are situated in the less affluent country group in terms of income PPP, and additionally, of the countries analysed, have the highest percentage of individuals living below 60% of the country median equivalent income. Both countries also display similarly low levels of tertiary education relative to other countries. The two countries furthermore have relatively low levels of health quality. This finding aligns with our expectation that opportunities for well-being, including the aspect of individual agency not captured in conventional happiness measures like overall happiness, may be reduced in less affluent countries, and can be linked to the proportion of highly educated individuals. The SWC measure, which captures individuals’ opportunities, can serve to reflect the role of individual agency for achieving well-being, and while further research would be needed, it could be conjectured that there is some context or policy-specific political infrastructure in Poland and Italy which may reduce individuals’ agency, and subsequently SWC.

We also observe that the biggest differences between measured SWC (MIMIC GEN) and overall happiness are noted in Italy and Poland (Fig. 8). It can be noted that this is again the case for two countries categorised as ‘less affluent’ and with the highest percentage of poor individuals. However, among these countries the relationship between SWC and overall happiness is inverse, that is, in Italy the estimated SWC is higher than the overall happiness measure, while in Poland the opposite relationship can be observed. We have two suggestions regarding this observation, which would warrant further study.

Firstly, as we have noted, SWC is to do with individual opportunity. In this way, it can bypass the problem of hedonic adaptation to deprived or difficult conditions. SWC as a measure can generate a different estimate to that of overall happiness if it controls for the problem of hedonic adaptation, which we suggest could be the case for Italy (France and Ireland), where SWC estimates are higher than overall happiness estimates. Opportunity-based measurement is in theory less vulnerable to hedonic adaptation than a measure of SWB because it leans on objective criteria (resources and conversion factors). In Poland, we observe a similar difference between the SWC and overall happiness estimate, but the inverse relationship, where SWC measures are higher than happiness measures. This suggests to us that there may be country-specific cultural and political contexts, namely specific policies, that can generate a difference in individuals’ happiness and opportunities. A specific policy could generate higher SWC than overall happiness in a given less affluent country, and higher happiness than SWC in a different less affluent country. For example, a particular retirement-related policy, such as the retirement age requirement, retirement replacement rate, quality of public services could generate the sense of more agency and opportunity in one country, but it is plausible that the same retirement policy, or indeed, a different one could generate the sense of less opportunity in another depending on the cultural context and how work is viewed and valued culturally and materially in the given country.

It may also be that certain highly valued functionings may produce a necessary trade-off with SWB functionings, with some functionings moving in the same direction, while others in conflicting directions. For example, the functioning of employment may move in the same positive direction as the functioning of ‘feeling happy’ or ‘feeling calm.’ In other instances, functionings may be rivalrous. If we consider the functioning of employment, for example, depending on the nature of the work, the functioning may be associated with negative SWB functionings, such as ‘feeling nervous’ or ‘feeling sad’. The concept of SWC takes on particular significance for this situation: it is the individual’s hierarchy of preferences and values that will determine the balance of functionings, including negative SWB functionings, that are pursued by the individual in achieving overall welfare. In particular, SWB functionings may not align with eudaimonic (worthwhile) functionings. In the situation of a trade-off between these categories and categories of other valuable functionings, the individual, exercising his agency, chooses the relevant balance in pursuit of overall welfare. The SWB account, on the other, makes no normative reference to agency.

We suggest that a similar logic regarding the differences in the country-specific policy contexts can be applied to understanding differences in SWC in specific domains such as retired/non-retired individuals as in Fig. 7 (MIMIC GEN), as well as the striking result of a notable discrepancy between overall happiness and SWC estimates throughout individuals’ lifespans in Italy (Fig. 9, Italy, MIMIC GEN). In the case of the latter (Fig. 9, Italy) what is observed is that opportunities for SWB functionings are higher than the happiness measure until about 60, after which point happiness measures are generally estimated as higher than SWC. Further investigation would be required to uncover what it is within the given policy or political context that might be influencing lower opportunities for well-being achievement for, in the cases of Poland and Italy (and Germany and France to a lesser extent), retired individuals. The case of Italy (Fig. 9) gives some plausible indication that policies dividing retired and non-retired individuals in Italy may be influencing the level of personal agency available to individuals at these different life stages.

Ireland presents an intriguing case study that reveals interesting insights. This country exhibits striking differences between SWC based on the tailored model and SWC based on the MIMIC GEN model (Fig. 8). From a statistical perspective, this peculiarity can be understood as the specific factors in Ireland lose their significance when included in a broader sample of all seven countries. However, Ireland's SWC, based on the tailored model, is significantly different from its average level of overall happiness, which sets it apart from other countries, too. We cannot rule out the possibility that there is a problem of hedonic adaptation, but we also hypothesise that the unique social conditions in this country, especially its young population and the associated high percentage of students and low percentage of retirees, conceal valuable information about social relationships. These factors, in turn, have an impact on SWC that is not apparent in an overall happiness variable. As shown by Berlingieri et al. (2023), loneliness is most prevalent in Ireland among European countries, with 20% of respondents reporting feeling lonely. These feelings are negatively correlated with age and positively correlated with experiencing major life events. For instance, individuals who finish their studies often feel more lonely due to their social circle suddenly shrinking. We observe that in our SWC model for Ireland, the age variable has a negative impact on SWC, while retirement status and economic activity have a positive impact, which lends credibility to our hypotheses. In general, Ireland's example convinces us that the set of resource variables should be expanded to include variables related to interpersonal relationships as social capital.

Not only does the lack of correlation between overall happiness and SWC based on the tailored model require attention, furthermore the alignment between SWC based on MIMIC GEN, overall happiness, and GDP per capita indicates a high correlation among these variables. These findings provide valuable guidance for the application of SWC. Instead of comparing SWC between countries using a common model (such as MIMIC GEN), it is preferable to utilise the simpler variable of 'overall happiness' or GDP per capita. However, for a deeper understanding of the specific factors influencing SWC in a given country, it is more suitable to employ SWC specifically designed for that country.

As we have endeavoured to demonstrate, the SWC aims to capture, and draws insight from the CA conceptual analysis. It brings to the fore the central CA concept of individual human agency. The SWC measure for a given country introduces the notion of agency in achieving well-being, which conventional overall happiness measures do not account for. Due to these specific features, SWC could hold great value in analysing migration movements. We can hypothesise, for example, that the opportunity to achieve happiness is one of the significant factors enabling migrants' assimilation in the host country.

Summary and Conclusion

The article introduces, measures, and discusses subjective well-being capability (SWC) as a consolidated measurement framework for subjective well-being (SWB) and the capability approach (CA). As a practical example, we estimated SWC for citizens of Poland and other selected European countries, identified based on their status as primary destinations for Polish emigrants. These estimates were made using the general model (MIMIC GEN) and specific models tailored to each country's unique context. Furthermore, we attempt to assess the usefulness of the SWC measure by comparing it with traditional well-being metrics like overall happiness (a measure of subjective well-being) and GDP per capita (a measure of objective well-being).

Our research yields several key findings. Firstly, there exists a significant correlation between SWC based on the MIMIC GEN model, overall happiness, and GDP per capita. When applying the same model to citizens from different countries, we note that higher average wealth and greater average happiness correspond with similarly elevated SWC values. This may be linked to similar underlying resources and conversion factors that are associated with SWB across all countries.

Secondly, country-specific SWC based on tailored models may significantly diverge from conventional well-being measures. This is particularly noticeable in the case of Ireland, where relatively high average overall happiness coexists with a low SWC. We have identified three potential reasons for this phenomenon. One might be tied to Ireland’s unique socio-economic factors, such as having the youngest population and the fewest retirees. Another possibility could be the unaccounted impact of the quality of social relationships on SWC, which is not explicitly represented in the model. Finally, an adaptation problem may exist, wherein some individuals report feeling happy even if objective conditions might not support this sentiment.

Thirdly, it is not only possible for the SWC, in terms of either the general or tailored MIMIC model, to be significantly lower than overall happiness, but the reverse can also occur. Italy and Poland provide clear examples of such a contrast. On one hand, we might hypothesise that large disparities between these two measures relate to the countries' relatively low wealth status, as both are classified as less affluent. On the other hand, we can speculate that a higher level of overall happiness and a lower level of SWC (as in Poland) may reveal an adaptation problem. Conversely, a higher level of SWC and a lower happiness level (as in Italy) might be associated with a trade-off faced by individuals striving to realise various available functionings, not exclusively related to happiness.

All of these observations lead us to the final conclusion that SWC encompasses additional information, compared to both subjective and objective well-being measures alone. This information pertains to the agency aspects of human welfare. This characteristic makes SWC useful for evaluating specific personal contexts (as demonstrated by the tailored models), though it may not necessarily serve as an ideal tool for country ranking (MIMIC GEN). Consequently, we posit that due to its agency aspect, the SWC could be a beneficial measure for critically evaluating ‘opportunities for happiness’, for example, in the social environment of immigrants, their countries of origin and their host societies.

While our study yields intriguing findings, we must acknowledge some limitations of our approach, related to both data quality and model specification. Concerning the data, our samples were drawn from a survey conducted in 2016, and, as of now, no more recent EQLS database has been made available. The dataset has a high percentage of missing data for some variables, which either precludes the use of these variables or necessitates their imputation. In terms of model specification, it's important to note that the distinction between resources and conversion factors is not clear-cut and context-dependent, making it challenging to create a more precise structural model. Furthermore, our model lacks variables directly associated with social capital. The use of SWC as a single index necessitates the coding of all variables as stimulants, which sometimes requires arbitrary decisions. Despite these drawbacks, we believe that further research on a unifying framework for SWB and CA is worth pursuing.

Notes

It is also worth noting that we do not intend to analyse the Polish diasporas in different countries.

MIMIC was formulated by Hauser and Goldberger (1971) and was later popularised by Jöreskog and Goldberger (1975). On the grounds of measurement and analysis of the level of well-being (capabilities) this model was used by Krishnakumar and Ballon (2008), Krishnakumar and Chávez-Juárez (2016), Zwierzchowski and Panek (2020), Lin et al. (2023).

References

Anand, P., Krishnakumar, J., & Tran, N. B. (2011). Measuring welfare: Latent variable models for happiness and capabilities in the presence of unobservable heterogeneity. Journal of Public Economics, 95(3–4), 205–215.

Bartram, D. (2011). Economic migration and happiness: Comparing immigrants’ and natives’ happiness gains from income. Social Indicators Research, 103, 57–76.

Berlingieri, F., Colagrossi, M., & Mauri, C. (2023). Loneliness and social connectedness: Insights from a new EU-wide survey (Report No. JRC133351). European Commission.

Binder, M. (2014). Subjective well-being capabilities: Bridging the gap between the capability approach and subjective well-being research. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(5), 1197–1217.

Burns, T. (2022). Amartya Sen and the capabilities versus happiness debate: An Aristotelian perspective. In F. Irtelli & F. Gabrielli (Eds.), Happiness and wellness: Biopsychosocial and anthropological perspectives. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.108512

Comim, F. (2005). Capabilities and happiness: Potential synergies. Review of Social Economy, 63(2), 161–176.

Dolan, P., Layard, R., & Metcalfe, R. (2011). Measuring subjective well-being for public policy. London School of Economics and Political Science, LSE Library. https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/35420/

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramovitz (pp. 89–125). Academic Press.

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. (2018). European Quality of Life Survey Integrated Data File, 2003-2016. [data collection]. 3rd Edition. UK Data Service. SN: 7348, 10.5255/UKDA-SN-7348-3

Graham, C., & Nikolova, M. (2015). Bentham or Aristotle in the development process? An empirical investigation of capabilities and subjective well-being. World Development, 68, 163–179.

Hauser, R. M., & Goldberger, A. S. (1971). The treatment of unobservable variables in path analysis. Sociological Methodology, 3, 81–117.

Hendriks, M., & Bartram, D. (2019). Bringing happiness into the study of migration and its consequences: What, why, and how? Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 17(3), 279–298.

Hoekstra, R. (2019). Replacing GDP by 2030: Towards a common language for the well-being and sustainability community. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108608558

Jöreskog, K. G., & Goldberger, A. S. (1975). Estimation of a Model with Multiple Indicators and Multiple Causes of a Single Latent Variable. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 70(351), 631–639.

Kogan, I., Shen, J., & Siegert, M. (2018). What makes a satisfied immigrant? Host-country characteristics and immigrants’ life satisfaction in eighteen European countries. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19, 1783–1809.

Kotan, M. (2010). Freedom or happiness? Agency and subjective well-being in the capability approach. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 39(3), 369–375.

Krishnakumar, J., & Ballon, P. (2008). Estimating Basic Capabilities: A Structural Equations Model Applied to Bolivia. World Development, 36(6), 992–1010.

Krishnakumar, J., & Chávez-Juárez, F. (2016). Estimating Capabilities with Structural Equation Models: How Well are We Doing in a ‘Real’ World? Social Indicators Research, 129, 717–737.

Kwarciński, T., & Ulman, P. (2018). A hybrid version of well-being: An attempt at operationalisation. Journal of Public Governance, 4(46), 30–49.

Layard, R., & De Neve, J. E. (2023). Wellbeing. Cambridge University Press.

Lin, Y. W., Lin, C. H., & Chen, C. N. (2023). Opportunities for Happiness and Its Determinants Among Children in China: A Study of Three Waves of the China Family Panel Studies Survey. Child Indicators Research, 16(2), 551–579.

Muffels, R., & Headey, B. (2013). Capabilities and choices: Do they make Sen’se for understanding objective and subjective well-being? An empirical test of Sen’s capability framework on German and British panel data. Social Indicators Research, 110(3), 1159–1185.

National Research Council. (2013). Subjective Well-Being: Measuring Happiness, Suffering, and Other Dimensions of Experience. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18548.

Ravazzini, L., & Chávez-Juárez, F. (2018). Which Inequality Makes People Dissatisfied with Their Lives? Evidence of the Link Between Life Satisfaction and Inequalities. Social Indicators Research, 137, 1119–1143.

Robeyns, I. (2017). Wellbeing, Freedom. Open Book Publishers.

Sarr, F., & Ba, M. (2017). The capability approach and evaluation of the well-being in Senegal: An operationalization with the structural equations models. Modern Economy, 8(1), 90–110.

Sen, A. (1979). Equality of What? In S. McMurrin (Ed.), The tanner lectures on human values (pp. 197–220). Cambridge University Press.

Sen, A. (1987). On Ethics and Economics. Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (1992). Inequality reexamined. Clarendon Press.

Sen, A. (1993). Capability and well-being. In M. Nussbaum & A. Sen (Eds.), The Quality of Life (pp. 30–53). Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (2005). Commodities and Capabilities. Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (2008). The economics of happiness and capability. In L. Bruni, F. Comim, & M. Pugno (Eds.), Capabilities and happiness (pp. 16–27). Oxford University Press.

Steckermeier, L. C. (2021). The Value of Autonomy for the Good Life. An Empirical Investigation of Autonomy and Life Satisfaction in Europe. Social Indicators Research, 154, 693–723.

van Hoorn, A. A. J., Mabsout, R., & Sent, E. M. (2010). Happiness and capability: Introduction to the Symposium. Journal of Socio-Economics, 39(3), 339–343.

Veenhoven, R. (2010). Capability and happiness: Conceptual difference and reality links. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 39(3), 344–350.

Voicu, B., & Vasile, M. (2014). Do ‘cultures of life satisfaction’ travel? Current Sociology, 62(1), 81–99.

Yeung, P., & Breheny, M. (2016). Using the capability approach to understand the determinants of subjective well-being among community-dwelling older people in New Zealand. Age and Ageing, 45(2), 292–298.

Zwierzchowski, J., & Panek, T. (2020). Measurement of Subjective Well-being under Capability Approach in Poland. Polish Sociological Review, 210(2), 157–178.

Funding

The publication was financed from the subsidy granted to the Krakow University of Economics—Project nr 084/EIT/2022/POT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwarciński, T., Ulman, P. & Wdowin, J. Measuring Subjective Well-being Capability: A Multi-Country Empirical Analysis in Europe. Applied Research Quality Life (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-024-10334-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-024-10334-9