Abstract

Hong Kong is characterized by extremely low fertility, with a total fertility rate of 0.701 in 2022. This paper reports significant declines in the intention to have children among non-parents and in the desire to have more children among parents, based on data from the Family Surveys conducted in Hong Kong in 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2017, which imply more dramatic demographic changes in the future. Drawing on the theory of planned behavior (TPB), this paper explored individuals’ attitudes toward marriage and having children, family functioning variables indicating subjective norms regarding fertility, and housing status and parenting stress relating to individuals’ control over fertility behavior. The results show that among non-parent respondents, being older and possessing a secondary education were associated with a lower level of fertility intention, whereas being a tenant, having positive attitudes toward marriage and having children, and having higher levels of family mutuality and harmony were associated with a higher level of fertility intention. Among parent respondents, parenting stress significantly inhibited the desire to have more children, regardless of financial matters and family environment. The findings suggest that fertility intentions can be remade over the life course. This paper, based on the TPB framework, can help guide the development and adoption of policies and supportive programs to improve fertility intentions in Hong Kong.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The global fertility rate has fallen considerably in the last several decades, from 4.7 in 1960 to 2.3 children per woman in 2021 (The World Bank, 2023). While high total fertility rates (TFRs) exist in some developing regions, many developed countries are experiencing a steady and continuous decline in their TFRs (Pezzulo et al., 2021). The more developed East Asian regions have even overtaken the West and have the lowest TFR in the world: 1.16, which is below the replacement level of 2.1 (Yong et al., 2019). South Korea has the lowest TFR, with 0.78 children per woman in 2022 (Poston, 2023). Japan’s TFR is also among the lowest in the world, having fallen to 1.26 children per woman in 2022 (Otake, 2023). Although a developing region, Mainland China’s TFR has also declined to 1.3 children per woman, according to its Seventh National Population Census (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2021). Hong Kong, one of the world’s most developed cities and a special administrative region in China, has an extremely low TFR, which has declined from 1.285 in 2012 to 0.701 in 2022 (Census and Statistics Department of Hong Kong, 2024).

The long-term consequences of enduring low TFR are overall negative and serious (Bujard, 2015). At the population level, low TFRs have tremendous impacts on different fields, including health, pensions, the labor market, etc., which influence individuals’ quality of life. For example, the increasing demand for long-term care and the financing of healthcare systems are mounting concerns (Fukawa, 2008). As the pension replacement rate may drop due to the low birth rate and a growing aging population, people will have to take more individual responsibility for elderly care (Bujard, 2015). Thus, low TFR can bring a wide array of policy changes, which may bring challenges for individuals and significantly affect their future quality of life. At the individual level, low TFRs can undermine social capital, with lower levels of stability and support provided by parent-child relationships and sibling relationships, which influence one’s quality of life.

Research has shown a positive but modest association between childbearing and people’s subjective levels of happiness (Aassve et al., 2012), which implies that fertility levels may, in part, reflect happiness. Couples predict whether their level of happiness will increase after having children; if that is the case, they will take the necessary steps to have children. In contrast, couples who predict low happiness are less likely to have children. For example, a decline in new parents’ life satisfaction is linked to reduced childbearing expectations (Luppi & Mencarini, 2018). However, it is also argued that in developed regions, self-realization and individualization have made having children less important in individuals’ lives (Aassve et al., 2012).

In this paper, we examine the trend of fertility intentions of Hong Kong people from 2011 to 2017 based on a four-wave Family Survey data set. We try to identify the factors associated with individuals’ fertility intentions, which can offer policymakers useful insights for developing appropriate pronatalist policies and enhancing social services to support families.

Fertility Intentions and Associated Factors

Surveys on fertility intentions are based on the assumption that having a child is a reasoned decision, especially among individuals in developed regions with ready access to contraception (Ajzen & Klobas, 2013). Low fertility intention is not equivalent to low fertility behavior; rather, there is a gap between intention and fertility at the individual level, as actual fertility levels are often lower than intended levels (Luo & Mao, 2014). Even so, fertility intention is a strong predictor of an individual’s childbirth-related behavior and is identified as a key factor explaining the fertility trends in different countries and regions (Schoen et al., 1999; Testa, 2014).

The trend of declining fertility is determined by several macro-level structural influences, including socioeconomic development (Anderson & Kohler, 2015), urbanization (Sato & Yamamoto, 2005), national fertility policy, and political factors (Wang & Sun, 2016). The individual’s childbirth decision is a multifaceted phenomenon with complex interactions between micro-level factors and these social, economic, and political forces (C.-K. Wong et al., 2011). Economic-based explanations have been widely used to explain the dynamics of fertility decisions. Demographers commonly use the concept of rationality to describe the process of fertility-related decision-making, in which individuals calculate the costs and benefits of childbirth and seek to maximize utility (Philipov, 2011). In a post-transitional society characterized by low birth and death rates, decisions on childbearing may be based on the relationship between the number of children and the opportunity cost of time, as raising children is a time and resource-intensive job (Becker, 1965). The decline in fertility is seen as a response of individuals and families to the risks and challenges associated with social and economic change. For example, high and persistent unemployment among women is associated with delays in childbearing and significantly depresses the fertility (Adsera, 2011). Prioritization of career over family is associated with less favorable attitudes toward marriage and having children and delays in childbearing, especially in developed East Asian countries, as the strong competition for prestigious jobs reduces the attainability of social status (Yong et al., 2019). However, the relationship between female education, employment, and fertility remains elusive. The negative correlation between fertility rate and female labor force participation was found to have reversed in some developed western countries by the 1990s (Brewster & Rindfuss, 2000). Evidence from European countries shows a positive relationship between women’s educational attainment and fertility intentions at both individual and country level (Testa, 2014).

Several individual, family, and relationship factors have been found to impact fertility intentions. For both women and men, age is a crucial factor in fertility intentions (Chen & Yip, 2017; Lacovou & Tavares, 2011). The gendered division of housework and childcare affects women’s fertility intentions, especially those with higher educational attainment (Cheng & Hsu, 2020), as working moms often have a heavy workload due to the unequal division of household labor (Chen & Yip, 2017; Mills et al., 2008). Changes in partnership dynamics in the post-transitional society significantly postpone the parenthood (Balbo et al., 2013).

Hong Kong as a Study Site

Policy to Encourage Childbirth and Gaps

Low TFR constitutes the greatest demographic change in Hong Kong society. Viewing childbearing as “a major family decision,” the Hong Kong government does not interfere with family decisions but has launched measures to foster a supportive environment for couples who wish to have children. To strengthen childcare and after-school care services, the government has been setting up more aided standalone childcare centers and providing resources for them to offer full-day, occasional childcare service and extended-hours service (Chief Secretary for Administration’s Office, 2015). Some family-friendly measures have been launched, including lengthening maternity and paternity leave (Labour Department, 2020). While offering direct cash subsidies may not be an effective way to raise fertility, given overseas experiences and the local situation, the government has launched several measures to help lessen the financial burden on families, including implementing free 12-year education and a child allowance under salaries tax. However, according to the census, the fertility rates have not rebounded as expected; indeed, they have fallen even further.

One important reason for this continued decline is that the overall development of family-friendly policies in Hong Kong is slow. For example, the supply of formal childcare services remains far from able to meet the demands of families, with especially severe shortfalls for those with children under two. In this paper, we argue that low individual fertility intention is another reason why these measures on fertility have little effect. Family-friendly policies are perceived as more important among women with fertility intentions than those without fields (C.-K. Wong et al., 2011). Therefore, to some extent, these measures are only effective for individuals who wish to have children. Though excessive intervention in families’ childbearing decisions is deemed inappropriate by the government, fostering a supportive environment to help encourage individuals’ fertility intentions can still be a viable path, filling the gaps in the policies that only aim at providing better support for families who wish to have children.

Literature on Fertility Intention and Gaps

To adopt timely and appropriate policies and services that aim to increase the fertility rate in Hong Kong, it is very important to understand the trend of individuals’ fertility intentions and the factors underlying them. The most recent study based on a survey in 2012 showed that the average actual parity among Hong Kong women was 1.3, lower than the average ideal parity of 1.7; and factors associated with first-birth intentions included marital satisfaction, household income, and communication with husbands in terms of childrearing (Chen & Yip, 2017). The current study is needed for the following reasons.

First, it is meaningful to examine the fertility intentions of people of both genders and different levels of parity. Most studies have examined fertility intentions among women only; fertility intentions among men have received less attention (Chen & Yip, 2017; Cheng & Hsu, 2020; Park et al., 2010; C.-K. Wong et al., 2011). While examining female fertility is an approach that obtains accurate TFRs, considering the importance of the involvement of men in fertility decisions and parenting, studies on men’s fertility intentions and comparisons between men and women are needed (Dudel & Klüsener, 2021).

Second, the formation of childbearing intentions is a dynamic process that changes as life unfolds. Hayford (2009) found that nonmarriage was associated with a decline in the intended family size, and early first birth was associated with an increase in the intended family size among US women in their life course. According to Lacovou and Tavares (2011), people are very likely to adjust their fertility expectations after the birth of their first child, so first-birth intentions are crucial determinants of the intention to have a second or subsequent child and affect TRF. The intentions of young adults to have their first child have received growing research attention in recent years (Karabchuk, 2020). As stable low-order live births are one of the most important factors underlying the trend of declining fertility in Hong Kong (Census and Statistics Department of Hong Kong, 2020), it is important to examine the fertility intentions of childless individuals, both those who do not have a partner and those who do.

Third, while individual characteristics, the wider sociocultural context, and social policies underlying individuals’ fertility intentions have been extensively examined in several large-scale population surveys, the role of family contextual factors in shaping fertility intentions requires more attention. Research has shown that a high-quality relationship between partners, an egalitarian division of housework, increased paternal investment in childcare, and help from relatives are associated with higher fertility intentions among women (Berninger et al., 2011; Chen & Yip, 2017; Cheng & Hsu, 2020; Park et al., 2010). More research examining the influences of family dynamics, including family functioning and parenting stress, is needed for a better understanding of the determinants of fertility intentions.

Fourth, Hong Kong faces escalating housing problems (H. Wong & Chan, 2019) characterized by chronic persistent shortages, extremely compact sizes, and unaffordability. Housing conditions were found to be significantly associated with fertility behaviors. Property ownership and spacious housing could facilitate the transition to parenthood (Kulu & Vikat, 2007; Mulder & Wagner, 2001). Furthermore, the degree to which people feel secure about their housing conditions was found to be positively associated with their intention to have children (Vignoli et al., 2013). Understanding the geographical variations in fertility intention by housing situations will provide valuable evidence for policymaking and service provision in Hong Kong.

The Theory of Planned Behavior

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) developed by Ajzen (1991) links fertility intention to actual fertility behavior. Scholars have criticized TPB for failing to explain the sufficient variability in behavior, which is linked to its limited predictive validity (Sniehotta et al., 2014). For example, people who form the fertility intention can subsequently fail to act, and fertility can also be unintended. Thus, it might be inappropriate to assume a clear intention preceding conception (Morgan & Bachrach, 2011). We agree with the existence of a gap between fertility intention and its realization; however, as the current study did not discuss to what extent fertility intention can predict fertility behavior, we deem the use of TPB to examine factors contributing to fertility intention as appropriate and have incorporated several critiques when adopting TPB.

While along with several dominant theoretical models that fertility is a result of rational decision-making, TPB did not assume economic rationality; instead, it builds a model of the social-psychological process involved in forming individuals’ fertility intentions (Ajzen & Klobas, 2013). Fertility behavior is the product of a person’s subjective weighting of attitudes toward having a child, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Attitudes toward fertility behavior, or fertility behavioral beliefs, refer to individuals’ evaluation or appraisal of the consequences of having a child, either positive or negative. Subjective norms refer to the perceived social pressure from important referents concerning having a child. Perceived behavior control refers to the perceived factors that influence an individual’s ability to realize their fertility intention, which can include past experiences and anticipated obstacles. Family systems, representing the fundamental structures in which family processes take place, were found to influence individuals’ fertility intentions by moderating their attitudes toward having a child and subjective norms (Mönkediek & Bras, 2018). For example, the frequency of contact with family members can positively influence individuals’ attitudes toward having a child. Thus, employing family system variables can lead to a better understanding of the pathway to fertility intentions.

It is criticized that TPB ignores some key factors of fertility but focuses on psychological antecedents only (Morgan & Bachrach, 2011). As discussed, there is consistent evidence that demographic characteristics (age, sex) and socio-economic status (education and income) can objectively predict fertility intention. Thus, the current study controlled for the individual demographic and socioeconomic factors when adopting TPB as a framework. Aiming to answer the question of what determines the intention to have a child in the first place, TPB can contribute to addressing the fertility differences among individuals with similar socioeconomic characteristics and are affected by similar social, structural, and cultural environments. While TPB was criticized for modeling fertility intention at a given point in time (Morgan & Bachrach, 2011), the current study accommodated a process in which childbearing planning may be remade over the course of life.

Most fertility research is conducted based on large-scale population surveys, often offering limited space for questions about individuals’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control. Thus, studies adopting TPB have built measures based on different items to act as proxies for individuals’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control to explain fertility intentions. A study using data from the Generations and Gender Survey (GGS) and the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) measured fertility attitudes by asking whether having a child would improve or worsen life aspects (Mönkediek & Bras, 2018). Another study based on a provincial fertility data set in China reflected the attitudes to fertility relating to child-value judgment and gender preference (Luo & Mao, 2014). In the current study, we assume that attitudes toward marriage and having children can imply an individual’s fertility attitude, along with the policies of several countries to boost fertility by promoting traditional marriage (Gubernskaya, 2010). Even among those who are married, heterogeneity in attitudes toward marriage and having children still exists.

Subjective norms are often measured with respect to the influences of influential individuals, including partners, parents, friends, and relatives. For example, Chinese people may consider the opinions of relatives or friends when planning to have a child (Luo & Mao, 2014). However, the approach that centered on the individual and considered only the influence of the perceived view of others cannot capture the complexity of fertility outcomes (Morgan & Bachrach, 2011). Research has shown that childless women with limited socioeconomic resources had higher fertility intentions if they lived near their parents, indicating the important role of support from geographically proximate parents (Raymo, 2010). In the research by Mönkediek and Bras (2018), the frequency of contact with family members at the regional level positively influenced fertility intentions by influencing individuals’ subjective norms, namely whether significant others thought they should have a child. As there is a lack of a direct measure of subjective norms in the Hong Kong Family Surveys, the current study considers the role of family functioning (mutual support, communication, and fewer conflicts) in Hong Kong families, indicating the potential influence of social norms.

While TPB was criticized for the lack of attention on material constraints and childrearing behavior (Morgan & Bachrach, 2011), a range of studies in the recent decade had involved these factors in examining perceived behavior control, including financial, housing, and health conditions (Mönkediek & Bras, 2018). Research has shown that women with higher levels of perceived control over housing conditions had higher fertility intentions (Vignoli et al., 2013). However, people’s fertility intentions can be frustrated by a lack of control over their psychological distress during child rearing (Hwang & Kim, 2021; Stykes, 2019). In the current study, we considered tenure of accommodation, number of children who need care, and parenting stress when examining perceived behavior control.

Exploring Fertility Intention and Understudied Determinants in the Hong Kong Context

In the lowest-low fertility context in Hong Kong, the first objective of the current study was to explore the trend of individuals’ fertility intentions using the data from four waves of the Hong Kong Family Survey. We examined the fertility intentions of both non-parents and parents in view of the sequential decision-making involved. Furthermore, we compared the fertility intentions of women and men in view of the role of men in fertility decisions and childcare. We hypothesized that (H1) there is a gender difference in first-birth intention as well as the intention to have a second or subsequent child.

The second objective was to examine the factors associated with fertility intentions at individual and family levels. We adopted TPB to examine individuals’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control concerning childbirth. As factors affecting fertility intention may vary due to childbirth conditions, we examined and compared the factors associated with fertility intentions of parents and non-parents. First, we examined the associations between fertility intentions and respondents’ demographic and socioeconomic (SES) factors. We hypothesized that (H2) being younger and in a stable relationship, having a lower education level, and being economically active are associated with higher levels of fertility intentions. Second, variables in TPB were examined after controlling for demographic and SES factors. We examined attitudes toward marriage and having children as attitudes toward childbirth. We hypothesized that (H3) having positive attitudes is associated with higher levels of fertility intentions. Perceived family functioning served as a proxy for opinions about the influences of significant individuals in social networks on the decision to have a child. High levels of family functioning mean family members are “bonded emotionally, communicate effectively, and respond to problems collaboratively” (Shek et al., 2015), which can offer a supportive and safe environment for raising children and cultivate a positive attitude toward having children. Thus, we hypothesized that (H4) higher levels of mutuality, communication, and harmony within the family and higher levels of family functioning are related to increased fertility intention. Housing conditions, the number of children who need care, and parenting stress were examined as perceived behavior control, as individuals may revise their fertility expectations downward if they find childcare stressful (Hwang & Kim, 2021). We hypothesized that (H5) being a tenant, having more children to take care of, and higher levels of parenting stress are negatively related to the desire to have more children among parents.

Methodology

Research Design and Sample

This study conducted a secondary analysis of the data from four waves of the Hong Kong Family Surveys conducted in 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2017. The surveys were cross-sectional in design, which did not include panel data. The surveys were commissioned by the Home Affairs Bureau of the government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The surveys provided updated information to track changes and development among Hong Kong families, covering different themes including family structure, family functioning, parenthood, etc. A two-stage stratified sample design was adopted. In the first stage, the frame of living quarters (LQs) was stratified by the geographical area and type of quarter. In the second stage, a household member aged 15 or above was randomly selected for the interview. In the present study, we chose a subsample of the respondents aged 15 to 44 and examined the trend of fertility intention across gender and predictors of intention. The final sample sizes for analysis of each wave were 813, 740, 637, and 1,064, respectively.

Measurements

Dependent Variables: Fertility Intentions of Non-Parents and Parents

We categorized the respondents into two groups: non-parent and parent. Non-parents were asked about their intention to have children, rated on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all likely to have children) to 4 (very likely to have children). The answers were recoded into a dichotomous variable (0 = not at all likely to and not likely to have children; 1 = likely to or very likely to have children). Parents were asked about their desire to have more children and the scale in the analysis was also dichotomous.

Explanatory Variables: Demographic and SES Factors and TPB Variables

We included several demographic factors that may influence fertility intentions, including respondents’ gender, age, and marital status. The respondents’ SES included education and economic activity status. Educational level was measured by the highest diploma/degree received and recoded on a three-point scale (0 = post-secondary education or above; 1 = primary or lower; 2 = secondary). Economic activity status was measured by whether the respondent was economically active or not.

Respondents’ attitudes toward marriage and having children were measured with four items: “marriage is a necessary step in life,” “married people are usually happier than people who have not yet married,” “life without children is empty,” and “childbearing is important in marriage.” The items were rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The reliability of this four-item index is satisfactory (α > 0.7).

Family functioning comprises five constructs: mutuality, communication, conflict and harmony, perceived overall family functioning, and satisfaction with family life. The first three constructs are related to family interaction and were measured using the subscales of the Chinese Family Assessment Instrument (C-FAI; Shek & Ma, 2010). Mutuality refers to “mutual support, love, and concern among family members” and was measured using a 12-item Likert scale; communication refers to “frequency and nature of interaction among family members” and was measured using a nine-item Likert scale; conflict and harmony refers to “conflict and harmonious behavior in the family” and was measured using a six-item Likert scale (Shek & Ma, 2010). Higher scores indicate better mutual support, communication, and fewer conflicts in the family. Cronbach reliability statistics for all the three scales were satisfactory (αs > 0.7). In addition, respondents rated their overall family functioning via a single item on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (does not function very well at all) to 5 (functions very well). Satisfaction with family life was also measured by a single item on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). It should be noted that respondents of different marital status can be subject to different forces and pressures in families.

Tenure of accommodation was measured by whether the respondent was an owner-occupier or a tenant. Parenting stress was assessed with a self-constructed questionnaire consisting of 10 Likert items. Items included: “most of my life is controlled by the needs of my child(ren),” “I have no private time,” “no one provides help when I am in need,” etc. The respondents indicated their level of agreement on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The reliability of this index is satisfactory (α > 0.7).

The questions were identical in each wave of the survey, except that fertility intention among parents was only examined in the second, third, and fourth waves of the Family Survey.

Statistical Analysis

First, descriptive analyses were conducted using percentages to examine the trend of fertility intention. We performed the analyses of parent and non-parent respondents separately and presented the fertility intention among female and male respondents. We also compared the fertility intention among parents with no child who needs caregiving, parents with one child who needs caring, and those with 2 children and above who need caring. Due to the small number of parent respondents, cross tabulation of the number of children by gender was not performed. Second, multiphase logistic regression analyses were performed to examine the factors associated with fertility intention among parent and non-parent respondents. The multiwave samples were combined to produce an aggregate sample in the regression analyses. In each multiphase logistic regression, we added dummy variables for the wave of the survey. Different logistic regression models were performed to evaluate the effects of different categories of predictor variables. A schematic diagram of the analytical model could be found in the appendix.

Results

Characteristics of Respondents

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the respondents of this study population. Significant differences between parent and non-parent groups were found in terms of most demographic characteristics across all four waves. There were proportionately more women than men in the parent group attending the questionnaire survey. Respondents in the parent group were older than the non-parent group (age difference > 8 years). In the parent group, most respondents were married, cohabiting, divorced, separated, or widowed; very few were unmarried. However, in 2017, the percentage of unmarried parents increased significantly, from around only 1–14.3%. In addition, in 2017, proportionately more families with children were living in tenant-owned accommodation. Finally, proportionately, more respondents in the non-parent group received post-secondary education or above.

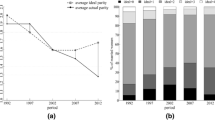

Decreasing Trend of Fertility Intention

Figure 1 reports the trends of fertility intentions of non-parents. We observe a decline in the intention to have children among non-parents of both genders over time. The overall intention to have children dropped significantly, by 18.9%, from 80.9% in 2011 to 62.0% in 2017. Female and male non-parent respondents’ intention to have children dropped by 19.9% and 17.9%, respectively. According to Fig. 2, the desire to have more children among parent respondents also exhibits a decreasing trend. The overall intention to have more children dropped significantly, by 6.8%, from 12.2% in 2013 to 5.4% in 2017. Female and male parent respondents’ desire to have children dropped by 4.2% and 7.4%, respectively.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of parent respondents’ desire to have more children according to the number of children they already need to take care of, and significant declines can be observed. Among parents with no child who needs caring, the desire to have more children dropped from 8.8% in 2013 to 4.0% in 2017. It should be noted that the criterion “with no child who needs caring” does not necessarily mean parity or that the parents were not responsible for childcare but indicates their children have grown older and do not need intensive parental care. Among parents with one child who needs caring, the desire to have more children dropped from 17.4 to 9.7%. And among parents with two children and above, the desire to have more children dropped from 6.7 to 1.5%.

Predictors of Fertility Intention

Table 2 presents the coefficients from logistic regression models predicting non-parent respondents’ intention to have children. In Model 1–1, we controlled for the wave of the survey, which showed significant decreases in fertility intentions in 2015 and 2017 compared to 2011. Models 1–2, 1–3, 1–4, and 1–5 identified the coefficients of demographic and SES factors, attitude factors, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control, respectively. Model 1–2 shows that respondents of older (OR = 0. 9, p < .001) with secondary education (OR = 0.7, p < .01) reported lower fertility intention, whereas respondents in a married or cohabiting relationship (OR = 2.07, p < .001) reported higher fertility intention. Model 1–3 shows that positive attitudes toward marriage and having children significantly increased the intention to have children in the future (OR = 2.62, p < .001). Model 1–4 shows that family mutuality was positively associated with fertility intention (OR = 1.44, p < .05). Model 1–5 shows that respondents who were tenants of rented accommodation (OR = 1.99, p < .001) reported a higher level of fertility intention. Furthermore, fertility intention was found to be associated with higher levels of family mutuality (OR = 1.48, p < .05) and harmony (OR = 1.56, p < .05). Model 1–5 increased from 4% in the base model to 32.1% in the final model.

Table 3 presents the coefficients from logistic regression models predicting parent respondents’ desire to have more children. Models 2 − 1, 2–2, 2–3, 2–4, and 2–5 identified the coefficients of survey waves, demographic and SES factors, attitude factors, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control, respectively. Model 2–2 shows that older (OR = 0.87, p < .001) had less desire to have more children. Models 2–3 and 2–4 show that attitudes toward marriage and having children and subjective norms were not related to fertility intention among parents. Model 2–5 shows that having fewer children to take care of correlated with a stronger desire to have more children. In addition, parenting stress significantly reduced the desire to have more children (OR = 0.28, p < .001). The Nagelkerke R Square increased from 2.6% in the base model to 29.2% in the final model.

Discussion and Conclusion

Fertility intentions were examined in the current study based on four waves of representative surveys on family issues in Hong Kong as a proximate cause for actual fertility behavior. First, we found that first-birth intentions declined significantly among individuals who did not have a child, from 80.9% in 2011 to 62.0% in 2017. Thus, there is a significant change in attitudes among people, whereby nearly half prefer not to have children. While the postponement of first births is a crucial determinant of low TFRs across countries (Billari & Kohler, 2004), we argue that the intention not to have children exerts even more downward pressure on fertility in Hong Kong. Second, fertility intention has declined significantly among parents, from 12.2% in 2013 to 5.4% in 2017. As the decline of fertility intention among parents is highly associated with their stopping behavior, it can contribute to the decline of fertility in Hong Kong. Overall, the findings are in alignment with the decline in fertility rate according to the census statistics. As several developed countries have seen a significant drop in birth rates during the COVID-19 pandemic (Aassve et al., 2021), the Hong Kong government may face more challenges in its attempts to stimulate the birth rate, which has remained very low for a long time.

In order to inform policymaking and service provision in the lowest-low fertility context in Hong Kong, it is important to understand the factors associated with low fertility intention. The current study found that age was a consistent factor affecting fertility intention. People who were older relatively did not expect a first child or subsequent child. However, no significant gender difference was found in terms of the fertility intentions of both non-parent and parent respondents. Thus, the results fail to confirm the hypothesis (H1). Yet, there was a trend toward significant differences before considering TPB components in the model. While the legal system and the Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC) of Hong Kong protect women’s opportunities in employment, education, and other prescribed areas of activity, gender inequality still exists in the household division of labor (Lee, 2011). The labor force participation rate of ever-married women was only 48.4%, compared with 69.5% for never-married women (EOC, 2021). As major caregivers of children, women in Hong Kong can face high levels of role conflicts between work and family, which lowers their fertility intentions.

Non-parent respondents with a secondary education reported a lower intention to bear children than those with post-secondary education or above after adjusting for other SES factors. This finding was inconsistent with hypothesis (H2) and presents a contrast with Japan and Korea, which are characterized by low gender egalitarianism. The incompatibility of childrearing and employment remains a significant challenge for highly educated married women in Japan and Korea (Brinton & Oh, 2019). In Hong Kong, childbearing and participation in the labor force might not be incompatible alternatives for people with higher levels of education, as better economic status or prospects allow them to engage a transnational (usually Filipino and Indonesian) domestic helper to perform household tasks and thus address some care and work conflicts (H. H. Chan & Latham, 2021). A previous study conducted in mainland China detected a U-shaped relationship between SES and fertility intention, suggesting that people in the middle of educational and income distributions have the lowest fertility intention (Zheng et al., 2009).

Drawing on the TPB framework, we adopted several items to measure attitudes, subjective norms, and control beliefs relating to fertility. In particular, we examined whether the dominating factors change as the fertility intention unfolds over the life course. Consistent with the theory, individual decision makers’ attitudes toward marriage and having children could be an important determinant of first-birth intention, as the non-parents who believed that marriage and children bring happiness were more likely to have fertility intentions, which is consistent with the hypothesis (H3). Furthermore, this study sheds light on the family environments under which fertility intentions are higher among non-parents. People who perceived their families as functioning well with fewer conflicts and more communications had higher first-birth intentions, which means that in forming the intention to have a child, people may consider influences from significant family members, which is consistent with the hypothesis (H4). The finding suggests that while self-realization and individualization have contributed to a diminished focus on the importance of having children among individuals in Hong Kong, the quality of the family environment, which is closely associated with subjective quality of life, can still exert an influence on fertility intentions.

This study found that among these non-parents, homeowners demonstrated lower fertility intentions than tenants. The finding is inconsistent with the hypothesis (H5); however, the counterintuitive relationship is consistent with a previous study on fertility intentions among the floating population in Mainland China (Zhou & Guo, 2020). According to Zhou and Guo (2020), homeownership may reduce the resources for childrearing when the family has limited economic resources. In Hong Kong, where private house prices are well-known to be unaffordable, housing has been a major concern for families and leads to deprivation (H. Wong & Chan, 2019); thus, families may have to make a choice between having a child and becoming a homeowner. In comparison, public rented housing is much more affordable, which may make people feel more capable of realizing their fertility intention. Thus, the geographical variations in terms of the type of housing could contribute to the variations in fertility intentions in Hong Kong.

Overall, positive attitudes toward family and having children, a warm and supportive family environment, and affordable accommodation can be prerequisites for becoming a parent. The findings of this study confirm the hypothesis that for non-parents, being younger and having positive attitudes toward marriage and having children, higher levels of family harmony and functioning were associated with higher levels of fertility intention. Some findings contradicted some of the hypotheses, as being the owner-occupier and having a lower educational level were associated with lower levels of fertility intention.

Among the parent respondents, SES, attitudes toward marriage and having children, and family functioning were not associated with the intention to have a second or subsequent child, which findings are inconsistent with hypotheses H3 and H4. The findings indicate that after the birth of a first child, the influences of most factors related to first-birth intentions become marginal. The number of children who need care was negatively associated with parents’ desire to have more children, as it can significantly increase parents’ childcare burden. Finally, the study captured parents’ experience of parenting stress, which was identified as a determinant of fertility intention. This finding is consistent with a previous study in Korea (Hwang & Kim, 2021). Finally, the findings partially confirmed hypotheses that being older (H2) and having a higher level of parenting stress and childcare burden (H5) were negatively associated with parents’ desire to have more children.

Limitations

The findings of this study should be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. First of all, due to data limitations, we were only able to examine whether or not the respondents had birth intentions rather than the number of children they wanted. As the proportion of households without children has increased significantly in Hong Kong, examining the intention to have children or not was perceived to be meaningful in this situation. While using dichotomous data can help compare the different waves of household surveys, the results cannot provide information about the level of attitudes toward having a child. As a secondary analysis, we were limited in what measures were available regarding family contextual factors and macro-level socioeconomic contexts. Future studies may examine the influence of family functioning across different family structures to understand better how these subjective norms affect people’s fertility intentions within different family contexts. Second, as new samples were drawn to Wave 2 and onward in the surveys, the analyses were based on cross-sectional data. Thus, we cannot determine the causal relationships between the individual- or family-level factors and fertility intentions. Third, it would be useful to adjust the data proportionally to accommodate the gender, age, and parental status of the respondents in the surveys. Regrettably, we were unable to ascertain the ratio between the survey data and the corresponding census data for each survey year with respect to the aforementioned variables. Thus, a weighting variable was not incorporated. Fourth, we did not use the multiple imputation when handling missing data. Fifth, it is unclear to what extent improving people’s fertility intentions can lead to an increase in Hong Kong’s fertility rate; thus, further studies evaluating the effects of relevant policy are needed. Despite this limitation, this study is among the first to examine the role of family contextual factors in forming fertility intentions. Future work using longitudinal data to establish a robust causal path to the low fertility intention is necessary. Perceived sociopolitical stability and the education system in Hong Kong may be examined in future studies (C. Chan & So, 2021). Finally, the determinants of fertility vary across countries with different sociocultural backgrounds and different income levels (Wang & Sun, 2016). Thus, generalization to other populations should be made with caution. Future studies can include participants in other geographical areas.

Implications for Policy and Practice

Low fertility rates have raised substantial concerns in developed countries, especially in East Asia. Even though a pronatalist policy package has been introduced in Hong Kong, the trend of declining fertility has not reversed, but has continued in recent years. With a significant downward trend of fertility intentions in Hong Kong in recent years and probable downward adjustments to fertility plans due to the COVID-19 crisis (Luppi et al., 2020), the low TFR will be maintained for a prolonged period. However, using the TPB framework, this study provides novel insights into the association between micro-level factors and fertility intentions, which can broaden our understanding of useful measures to boost fertility.

This is a priority policy area in Hong Kong, and in addition to supporting couples who already have birth plans, population policy needs more emphasis on boosting people’s intention to have children. While childbearing is a family decision that the government should not interfere with, the government can still be proactive and remove barriers that negatively influence the intention to have children. For example, in view of the unequal division of housework and childcare between family members, educational programs to promote gender equality in the private sphere are needed. This cost-effective measure can provide long-term benefits and ultimately lead indirectly to upward adjustments to fertility intentions. Improving housing affordability (e.g., increasing the public housing supply) would help reduce the economic burden on families and lessen the competition between home ownership and childrearing (Zhou & Guo, 2020). Importantly, the housing crisis is a chronic and pressing issue in Hong Kong whose resolution would bring tremendous benefits to individuals, families, and wider society.

Other measures aiming to reduce childcare burden and foster a supportive family environment may be considered. As parents’ intentions to have more children are very low following the birth of their first child, policies or services that encourage them to revise their fertility intentions upward are necessary. It seems that financial matters are a minor consideration for parents when deciding whether or not to have a second or subsequent child. The current study suggests it is more important to ease parenting stress. For example, with more formal childcare support, women can feel that they have greater control over the factors that constrain fertility, such as education and employment opportunities. However, it should be noted that the design of family assisting policies may not be able to affect fertility intentions if there is a gap between adopting the policies and their actual implementation as intended (Choi et al., 2018). Also, the family assisting policies need to be parity-specific, as the effects on fertility intentions differ by parity (Kim & Parish, 2022). Families that function well foster the well-being of family members, cultivate positive attitudes toward marriage and having children, and complement the lack of formal childcare to some extent. A study conducted in Korea shows that childcare support from relatives (e.g., paternal or maternal grandparents) can increase the likelihood of having a second child (Park et al., 2010). Encouraging the involvement of grandparents in childcare might help to boost fertility intention, and also promote healthy and productive aging. Pilot projects to improve family functioning and increase family members’ participation in childcare need to be launched to provide actionable policy solutions.

In sum, the significant declines in fertility intentions among both parents and non-parents suggest that the pronatalist services and policies in Hong Kong should be further improved. The findings of analyses drawing on TPB imply the need for introducing more family-friendly policies, implementing services that foster a supportive family environment, and improving people’s perceived control over housing conditions. While the population policies may take effect slowly, these measures will still increase individuals’ quality of life.

References

Aassve, A., Goisis, A., & Sironi, M. (2012). Happiness and childbearing across Europe. Social Indicators Research, 108, 65–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9866-x.

Aassve, A., Cavalli, N., Mencarini, L., Plach, S., & Sanders, S. (2021). Early assessment of the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and births in high-income countries. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(36), e2105709118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2105709118.

Adsera, A. (2011). Whereare the babies? Labor market conditions and fertility in Europe. European Journal of Population / Revue Européenne De Démographie, 27(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-010-9222-x.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen, I., & Klobas, J. (2013). Fertility intentions: An approach based on the theory of planned behavior. Demographic Research, 29, 203–232. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2013.29.8.

Anderson, T., & Kohler, H. P. (2015). Low fertility, socioeconomic development, and gender equity. Population and Development Review, 41(3), 381–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00065.x.

Balbo, N., Billari, F. C., & Mills, M. (2013). Fertility in advanced societies: A review of research. European Journal of Population, 29(1), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-012-9277-y.

Berninger, I., Weiß, B., & Wagner, M. (2011). On the links between employment, partnership quality, and the intention to have a first child. Demographic Research, 24, 579–610. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2011.24.24.

Billari, F., & Kohler, H. P. (2004). Patterns of low and lowest-low fertility in Europe. Population Studies, 58(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472042000213695.

Brewster, K. L., & Rindfuss, R. R. (2000). Fertility and women’s employment in industrialized nations. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 271–296. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.271.

Brinton, M. C., & Oh, E. (2019). Babies, work, or both? Highly educated women’s employment and fertility in East Asia. American Journal of Sociology, 125(1), 105–140. https://doi.org/10.1086/704369.

Bujard, M. (2015). Consequences of enduring low fertility – a German case study. Demographic projections and implications for different policy fields. Comparative Population Studies, 40, https://doi.org/10.12765/CPoS-2015-06. SE-Research Articles.

Census and Statistics Department of Hong Kong (2024). Hong Kong Monthly Digest of Statistics (February 2024). https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/EIndexbySubject.html?pcode=B1010002&scode=460#section3

Chan, H. H., & Latham, A. (2021). Working and dwelling in a global city: Going-out, public worlds, and the intimate lives of migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.2000854.

Chan, C., & So, Y. K. G. (2021). Adding fuel to the flame of low fertility: Fertility intention and perceived socio-political stability of young adults in Hong Kong. Human Reproduction, 36(Supplement_1). deab130.479.

Chen, M., & Yip, P. S. F. (2017). The discrepancy between ideal and actual parity in Hong Kong: Fertility desire, intention, and behavior. Population Research and Policy Review, 36(4), 583–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-017-9433-5.

Cheng, Y. A., & Hsu, C. H. (2020). No more babies without help for whom? Education, division of labor, and fertility intentions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(4), 1270–1285. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12672.

Chief Secretary for Administration’s Office (2015). Population and Policy Strategies Initiatives.

Choi, S., Yellow Horse, A. J., & Yang, T. C. (2018). Family policies and working women’s fertility intentions in South Korea. Asian Population Studies, 14(3), 251–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2018.1512207.

Dudel, C., & Klüsener, S. (2021). Male–female fertility differentials across 17 high-income countries: Insights from a new data resource. European Journal of Population, 37(2), 417–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-020-09575-9.

EOC (2021). Gender equality in Hong Kong.

Fukawa, T. (2008). The effects of the low birth rate on the Japanese social security system. The Japanese Journal of Social Security Policy, 7(2), 57–66.

Gubernskaya, Z. (2010). Changing attitudes toward marriage and children in six countries. Sociological Perspectives, 53(2), 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1525/sop.2010.53.2.179.

Hayford, S. R. (2009). The evolution of fertility expectations over the life course. Demography, 46(4), 765–783. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0073.

Hwang, W., & Kim, S. (2021). Husbands’ childcare time and wives’ second-birth intentions among dual-income couples: The mediating effects of work–family conflict and parenting stress. Journal of Social Service Research, 47(6), 850–859. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2021.1936746.

Karabchuk, T. (2020). Job instability and fertility intentions of young adults in Europe: Does labor market legislation matter? The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 688(1), 225–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716220910419.

Kim, E. J., & Parish, S. L. (2022). Family-supportive workplace policies and benefits and fertility intentions in South Korea. Community Work & Family, 25(4), 464–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2020.1779032.

Kulu, H., & Vikat, A. (2007). Fertility differences by housing type: The effect of housing conditions or of selective moves? Demographic Research, 17, 775–802. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26347971

Labour Department (2020). The Employment (Amendment) Ordinance.

Lacovou, M., & Tavares, L. P. (2011). Yearning, learning, and conceding: Reasons men and women change their childbearing intentions. Population and Development Review, 37(1), 89–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00391.x.

Lee, E. W. Y. (2011). Gender and change in Hong Kong: Globalization, postcolonialism, and Chinese patriarchy. UBC.

Luo, H., & Mao, Z. (2014). From fertility intention to fertility behaviour. Asian Population Studies, 10(2), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2014.902162.

Luppi, F., & Mencarini, L. (2018). Parents’ subjective well-being after their first child and declining fertility expectations. Demographic Research, 39, 285–314. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2018.39.9.

Luppi, F., Arpino, B., & Rosina, A. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on fertility plans in Italy, Germany, France, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Demographic Research, 43, 1399–1412. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2020.43.47.

Mills, M., Mencarini, L., Tanturri, M. L., & Begall, K. (2008). Gender equity and fertility intentions in Italy and the Netherlands. Demographic Research, 18, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2008.18.1.

Mönkediek, B., & Bras, H. (2018). Family systems and fertility intentions: Exploring the pathways of influence. European Journal of Population, 34(1), 33–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-017-9418-4.

Morgan, S. P., & Bachrach, C. A. (2011). Is the Theory of Planned Behaviour an appropriate model for human fertility? Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 9, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1553/populationyearboo

Mulder, C. H., & Wagner, M. (2001). The connections between family formation and first-time home ownership in the context of west Germany and the Netherlands. European Journal of Population, 17(2), 137–164. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010706308868

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2021). Main results of the Seventh National Census.

Otake, T. (2023). Japan’s fertility rate matches record low as it drops for seventh consecutive year. The Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/06/02/national/2022-birthrate-record-low/.

Park, S. M., Cho, S. I., & Choi, M. K. (2010). The effect of paternal investment on female fertility intention in South Korea. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31(6), 447–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.07.001.

Pezzulo, C., Nilsen, K., Carioli, A., Tejedor-Garavito, N., Hanspal, S. E., Hilber, T., James, W. H. M., Ruktanonchai, C. W., Alegana, V., Sorichetta, A., Wigley, A. S., Hornby, G. M., Matthews, Z., & Tatem, A. J. (2021). Geographical distribution of fertility rates in 70 low-income, lower-middle-income, and upper-middle-income countries, 2010–16: A subnational analysis of cross-sectional surveys. The Lancet Global Health, 9(6), e802–e812. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00082-6.

Philipov, D. (2011). Theories on fertility intentions: A demographer’s perspective. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 9, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1553/populationyearbook2011s37.

Poston, D. L. (2023). South Korea has the lowest fertility rate in the world - and that doesn’t bode well for its economy. The Concersation.

Raymo, J. M., Mencarini, L., Iwasawa, M., & Moriizumi, R. (2010). Intergenerational proximity and the fertility intentions of married women. Asian Population Studies, 6(2), 193–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2010.494445.

Sato, Y., & Yamamoto, K. (2005). Population concentration, urbanization, and demographic transition. Journal of Urban Economics, 58(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2005.01.004.

Schoen, R., Astone, N. M., Kim, Y. J., Nathanson, C. A., & Fields, J. M. (1999). Do fertility intentions affect fertility behavior? Journal of Marriage and Family, 61(3), 790–799. https://doi.org/10.2307/353578.

Shek, D. T. L., & Ma, C. M. S. (2010). The Chinese Family Assessment Instrument (C-FAI): Hierarchical confirmatory factor analyses and factorial invariance. Research on Social Work Practice, 20(1), 112–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731509355145.

Shek, D. T. L., Xie, Q., & Lin, L. (2015). The impact of family intactness on family functioning, parental control, and parent–child relational qualities in a Chinese context. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 2, 149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2014.00149.

Sniehotta, F. F., Presseau, J., & Araújo-Soares, V. (2014). Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychology Review, 8(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2013.869710.

Stykes, J. B. (2018). Gender, couples’ fertility intentions, and parents’ depressive symptoms. Society and Mental Health, 9(3), 334–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156869318802340

Testa, M. R. (2014). On the positive correlation between education and fertility intentions in Europe: Individual- and country-level evidence. Advances in Life Course Research, 21, 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2014.01.005.

The World Bank (2023). Fertility Rate, total (births per woman). https://genderdata.worldbank.org/indicators/sp-dyn-tfrt-in/?view=trend.

Vignoli, D., Rinesi, F., & Mussino, E. (2013). A home to plan the first child? Fertility intentions and housing conditions in Italy. Population, Space and Place, 19(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1716

Wang, Q., & Sun, X. (2016). The role of socio-political and economic factors in fertility decline: A cross-country analysis. World Development, 87, 360–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.07.004.

Wong, H., & Chan, S. (2019). The impacts of housing factors on deprivation in a world city: The case of Hong Kong. Social Policy & Administration, 53(6), 872–888. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12535.

Wong, C. K., Tang, K. L., & Ye, S. (2011). The perceived importance of family-friendly policies to childbirth decision among Hong Kong women. International Journal of Social Welfare, 20(4), 381–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2010.00757.x.

Yong, J. C., Li, N. P., Jonason, P. K., & Tan, Y. W. (2019). East Asian low marriage and birth rates: The role of life history strategy, culture, and social status affordance. Personality and Individual Differences, 141, 127–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.01.009.

Zheng, Z., Yong, C., Wang, F., & Gu, B. (2009). Below-replacement fertility and childbearing intention in Jiangsu Province, China. Asian Population Studies, 5(3), 329–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730903351701.

Zhou, M., & Guo, W. (2020). Fertility intentions of having a second child among the floating population in China: Effects of socioeconomic factors and home ownership. Population Space and Place, 26(2), e2289. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2289.

Acknowledgements

The work described in this paper used information/data obtained from an exercise commissioned and funded by the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Funding

This work was supported by The Home Affairs Bureau of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Ref: HAB RMU 3–5/25/1/100/19).

Open access funding provided by The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval

The study involved secondary data analysis and ethics approval was approved by the Home Affairs Bureau of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, M., Lo, C.K.M., Chen, Q. et al. Fertility Intention in Hong Kong: Declining Trend and Associated Factors. Applied Research Quality Life 19, 1309–1335 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-024-10292-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-024-10292-2