Abstract

This study offers both the first systematic investigation of the relationship between the five-factor personality model and general (ostensibly non-problem) lottery gambling, and the first application of Thompson and Prendergast’s (2013) bidimensional model of luck beliefs to gambling behavior. Cross-sectional analyses (N = 844) indicate the bidimensional model of luck beliefs significantly accounts for variance in lottery gambling that is discrete from and greater than that of the five-factor personality model. Moreover, the broad pattern of relationships we find between presumably harmless state-sponsored lottery gambling and both personality and luck beliefs tend to parallel those found in studies of problem gambling, suggesting implications for quality of life and public policy in relation to lottery gambling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

“A lottery is a taxation upon all the fools in creation”, suggests Fielding’s 1732 comic opera, The Lottery (2004, p. 2). Unfairness to fools aside, if this was lottery gambling’s most serious aspect it would be of scant scholarly or practical interest outside fiscal studies (Trousdale and Dunn 2014; for review see Perez and Humphreys 2011). But chancing one’s luck on the “light drug” (Thege and Hodgins 2014, p. 29) of state-sponsored lottery gambling is not simply a harmless, recession-proof form of raising government revenue (Horváth and Paap 2012). State-sponsored lottery gambling is indulged in by nearly 80% of people in some countries (Wardle et al. 2011) and is especially prevalent amongst the economically and educationally impoverished (Barnes et al. 2011; Beckert and Lutter 2009; Blalock et al. 2007; Kaizeler et al. 2014), who, further, are found to lose a higher proportion of their income in lottery gambling than higher socio-economic groups (Hansen et al. 2000; Lang and Omori 2009).

Moreover, while state-sponsored lottery gambling is often regarded as just another harmless consumer product (Borch 2012), it is advertised deliberately to appeal directly to young people (McMullan and Miller 2009), and is indulged in, often illegally, by the majority of minors (Felsher et al. 2004). Participation in national lotteries has also been linked to gambling addiction (Guryan and Kearney 2010), the crowding-out of productive investment (Dorn et al. 2015), higher suicide rates (Chen et al. 2012), and to increasing the likelihood that children of lottery gamblers will develop gambling problems in later life (Felsher et al. 2004). Hence, state-sponsored and heavily marketed lottery gambling has a public welfare and quality of life aspect that extends beyond mere revenue raising for governments.

However, while the personality determinants of comparatively rare problem gambling have received considerable attention (Miller et al. 2013; Mishra et al. 2010; Phillips and Ogeil 2011), the relationship between personality and more general and ostensibly innocuous gambling like state-sponsored lotteries has, as Rodgers et al. (2009) attest, been under-researched. Hence, for instance, although Balabanis (2002) has investigated how problem lottery gambling relates to the five-factor model of basic personality, Miller et al. (2013) emphasize that the results of such studies have been inconsistent, and the sparse extant research on more general state-sponsored lottery gambling has still not yet directly considered the model (Cook et al. 1998; Griffiths and Wood 2001). Jaunky and Ramchurn’s (2014) research specifically on buying scratch-card, another form of general gambling sometimes state-sponsored and often considered harmless like national lotteries, have found the five-factor personality model predicts participation. However, Abarbanel (2014) finds evidence that lottery gambling is not predicted by precisely the same determinants as other forms of gambling, emphasizing the need for bespoke research specifically on the relationship between state-sponsored lottery gambling and the five-factor personality model.

In their paper on lottery gambling, Cook et al. (1998) highlight that certain personality constructs such as sensation seeking (Balodis et al. 2014; Buelow and Suhr 2013; Cyders and Smith 2008), risk-taking (Carver and McCarty 2013), affect (Sundqvist and Wennberg 2015), and impulsivity (Demaree et al. 2008; MacLaren et al. 2012) have tended to constitute the primary foci of much gambling research. Consequently, other personality constructs potentially affecting state-sponsored lottery gambling, such as luck beliefs, have received relatively little attention. Indeed, Ariyabuddhiphongs (2011) laments that the effect of “perceived luckiness has not been tested among lottery gamblers” (p. 19). While cognate superstitious beliefs and lottery gambling have received some attention (Ariyabuddhiphongs and Chanchalermporn 2007; Pravichai and Ariyabuddhiphongs 2014), the lacuna of research specifically on luck beliefs and state-sponsored lottery participation remains.

To address these shortfalls in extant research, we examine the effects on state-sponsored lottery gambling of the five-factor personality model and Thompson and Prendergast’s (2013) relatively recently developed bidimensional refinement of trait luck beliefs, both separately and in combination.

Five-Factor Model and Lottery Gambling

Extraversion

The extraversion component of the five-factor model taps the degree to which individuals tend to exhibit characteristics such as sociability and being outgoing (Digman 1990; Goldberg 1993). Balabanis (2002) finds Extraversion positively predicts problem lottery gambling. His result accords both with Zuckerman and Kuhlman (2000) who find a correlation between general gambling and sociability, an Extraversion-related trait. However, other researchers find problem gamblers score significantly lower on Extraversion than non-problem gamblers (Myrseth et al. 2009). Because general state-sponsored as opposed to problem lottery gambling is often a social activity involving informal syndicates of friends and colleagues sharing tickets (Humphreys and Perez 2013), we hypothesize it should be associated with individuals having more outgoing personalities, hence:

-

H1. Extraversion will positively predict state-sponsored lottery gambling.

Openness

The openness to experience facet of the five-factor model captures the extent to which individuals are intellectual, imaginative and cognitively curious (Digman 1990; Goldberg 1993). Openness is found by Balabanis (2002) negatively to predict problem lottery gambling. This accords with similar findings in several studies of problem gambling (Chiu and Storm 2010; Hwang et al. 2012; Miller et al. 2013; Myrseth et al. 2009). Because lotteries constitute solely chance-based ‘lucky’ draws which have been shown to be appraised at least partially on a rational basis (Prendergast and Thompson 2013), we expect those scoring higher on Openness to be both more likely to appraise, and better at appraising, winning odds and therefore less likely to lottery gamble, hence:

-

H2. Openness will negatively predict state-sponsored lottery gambling.

Neuroticism

The neuroticism element of the five-factor model reflects how much individuals tend to be anxious, moody and emotionally unstable (Digman 1990; Goldberg 1993). Considerable research reveals a significant positive relationship between problem gambling and Neuroticism (Bagby et al. 2007; Chiu and Storm 2010; Miller et al. 2013; MacLaren et al. 2011b; Myrseth et al. 2009). But for general gambling Zuckerman and Kuhlman (2000) find no correlation between general gambling and Neuroticism. As most state-sponsored lottery gambling constitutes general as opposed to problem gambling, we do not anticipate it to be associated with Neuroticism, hence:

-

H3. Neuroticism will not significantly predict state-sponsored lottery gambling.

Conscientiousness

The conscientiousness component of the five-factor model assesses the degree to which individuals tend to be organized, dilgent and reliable (Digman 1990; Goldberg 1993). Although Balabanis (2002) finds no relationship between Conscientiousness and problem lottery gambling, research on problem gambling usually finds a negative relationship with Conscientiousness (Bagby et al. 2007; Hwang et al. 2012; MacLaren et al. 2011a, 2011b; Myrseth et al. 2009). We speculate that Balabanis’ (2002) finding may reflect the fact that his model includes a variable for cigarette consumption which, being negatively predicted by Conscientiousness (Malouff et al. 2006), may have partialled out a significant negative relationship between Conscientiousness and problem lottery gambling. Bogg and Roberts (2004) find Conscientiousness is negatively related to several risk-taking activities in a general population, hence we hypothesize:

-

H4. Conscientiousness will negatively predict state-sponsored lottery gambling.

Agreeableness

The agreeableness facet of the five-factor model reflects the extent to which individuals tend to be kind, compassionate and cooperative (Digman 1990; Goldberg 1993). Balabanis (2002) finds Agreeableness negatively predicts problem lottery gambling, in line with other research on problem gambling (MacLaren et al. 2011a, 2011b; Myrseth et al. 2009). More general gambling by hand-phone, that is reasonably closely analogous with general state-sponsored lottery gambling, is also found to be negatively predicted by Agreeableness (Phillips et al. 2006), hence we suggest:

-

H5. Agreeableness will negatively predict state-sponsored lottery gambling.

Luck Beliefs and Gambling

Cognitions of luck form a central theme in gambling research (McInnes et al. 2014), with luck believers found to be more frequent, higher risk taking, and more problematic gamblers (Chiu and Storm 2010; Friedland 1998; Wohl and Enzle 2002, 2003; Wohl et al. 2005). The little extant literature on luck beliefs and specifically state-sponsored lottery gambling reveals seemingly incompatible findings: Watt and Nagtegaal (2000) find that belief in having luck has no effect on state-sponsored lottery gambling, despite participation being found higher amongst those who believe luck determines lottery outcomes (Rogers and Webley 2001; Zhou et al. 2012).

However, all research on gambling and luck beliefs has hitherto been constrained by somewhat limited conceptualizations of luck beliefs and measures which either erroneously conflate or spuriously subdivide empirically distinct luck constructs. Some researchers have adapted portions of the Gamblers Beliefs Questionnaire (Steenbergh et al. 2002) to measure luck beliefs (Wohl et al. 2005) or have used their own measures (Zhou et al. 2012), but most have used Darke and Freedman’s (1997) Belief in Good Luck Scale. This scale is intended, and has usually been used, as a unidimensional measure (e.g. Chiu and Storm 2010; Wohl and Enzle 2002, 2003). However, subsequent researchers (André 2009; Öner-Özkan 2003) and Darke and Freedman (1997) themselves have found this scale to be somewhat problematic in that not only is it unable to discriminate between respondents believing themselves, respectively, lucky or unlucky, but that it also captures not a unidimensional but a multidimensional luck belief construct. Specifically, in a factor analysis of their measure, Darke and Freedman (1997, p. 493, fn. 3) report a bidimensional solution that appears to separate discrete constructs representing, respectively, believing in luck as a force external to an individual that shapes the future, and belief in how lucky oneself might be. Prendergast and Thompson (2008) also report finding these two discrete dimensions of luck belief when using Darke and Freedman’s (1997) measure, and moreover find that each dimension differentially predicts preferences for participation in sales promotion lotteries.

Shortcomings with Darke and Freedman’s scale have prompted a series of luck belief reconceptualizations (André 2006; Maltby et al. 2008; Young et al. 2009). These have culminated in Thompson and Prendergast’s (2013) systematically developed and validated bidimensional model of luck beliefs comprising discrete components of, on one hand, belief in luck as a deterministic phenomenon influencing future events (Belief in Luck) and, on the other, belief in being personally lucky or unlucky (Belief in Personal Luckiness). Thompson and Prendergast (2013) found Belief in Luck and Belief in Personal Luckiness to be discrete, unidimensional and uncorrelated components of trait luck beliefs, applicable to both luck believers and disbelievers alike. This relatively recently developed bidimensional conceptualization and measurement of luck beliefs now offers a conceptually and metrically robust basis for theorizing the relationship between luck beliefs and gambling in general and, for our purposes, lottery gambling in particular.

Belief in Luck

Thompson and Prendergast (2013) find support for Maltby et al.’s (2008) suggestion that the implicit irrationality of belief in luck is a reflection of personal maladaptivity. Miller et al. (2013) suggest problem gambling could be a maladaptive coping strategy, indicating that belief in luck might be associated with problem gambling. This supposition is supported by Thompson and Prendergast’s (2013) finding that Belief in Luck correlates positively with both Neuroticism, which has been found to predict gambling risk-taking (Buelow and Suhr 2013; Miller et al. 2013), and negative affect, which has also been found to predict problem gambling (Atkinson et al. 2012; Moore et al. 2013). Moreover, Wu et al. (2012) find that problem gambling correlates with belief in luck, whereas non-problem gambling does not. Hence, if state-sponsored general lottery gambling is broadly a harmless entertainment qualitatively different to maladaptivity-related problem gambling, we would anticipate Belief in Luck either to be unassociated or perhaps even negatively associated with state-sponsored lottery gambling participation, hence:

-

H6. Belief in Luck either will not significantly or will negatively predict state-sponsored lottery gambling.

Belief in Personal Luckiness

Belief in Personal Luckiness was speculated by Thompson and Prendergast (2013) to constitute a facet of overall subjective wellbeing as they found it correlated positively with measures of affect.

Negative affect is generally associated positively with problem gambling (Moghaddam et al. 2014). However, while positive affect is negatively associated with problem gambler samples (Hwang et al. 2012), it is positively associated with higher betting among non-problem-gambler student samples (Cummins et al. 2009). Optimism is also found in non-problem-gambler student samples to be associated with greater expectations of winning and with post-bet-loss gambling continuance (Gibson and Sanbonmatsu 2004). Belief in Personal Luckiness may therefore, like positive affect and optimism, constitute a facilitator of cognitive distortion of gambling-outcome expectations that increases general gambling participation (Fortune and Goodie 2012), including gambling on state-sponsored lotteries, hence:

-

H7. Belief in Personal Luckiness will positively predict state-sponsored lottery gambling.

Relationship between Luck Beliefs and Five-Factor Model

As the five-factor model is generally regarded as capturing fundamental personality traits (Goldberg 1993), we expect luck beliefs to stem from personality rather than the other way around. Accordingly, to the extent that luck beliefs account for any variation in state-sponsored lottery participation, we would expect this to be partialled out by fundamental personality, hence:

-

H8. The five-factor model will account for any effect of luck beliefs on state-sponsored lottery gambling.

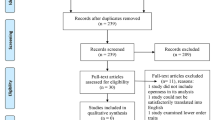

Methods

Participants and Procedure

An online instrument was sent to volunteers who, in accordance with research ethics requirements of our respective institutions, gave informed consent for its receipt, were free to withdraw from instrument completion at any point, and who had been assured their responses would be both (i) anonymous and (ii) used only for academic research.

We sought a socio-economically, educationally, and culturally homogeneous population to help ameliorate the known effects of socio-economic, educational and cultural factors on gambling (Barnes et al. 2011; Beckert and Lutter 2009; Blalock et al. 2007; Kaizeler et al. 2014). Accordingly, our sample comprised 623 female and 221 male, ethnically Chinese students from an English-language university in Hong Kong. They comprised both undergraduates and postgraduates, aged 18 to 59 years (mode age category 20–24, 59%), studying a range of science, social science, humanities and vocational disciplines.

Measures

Lottery Gambling

Following (Li et al. 2012), we asked participants how frequently they had bought Hong Kong government-sponsored Mark-Six Lottery tickets in the preceding 12 months. The Mark Six lottery is ubiquitously known and popular in Hong Kong, with around 24 million tickets sold per draw in an adult population of around just 6 million. Similarly to Cook et al.’s (1998) study of state-sponsored lottery gambling in the UK, we assessed lottery participation using bands of lottery-ticket purchase frequency over the previous 12 months (Never, Once or twice, Several times, Once or twice every month, Once or twice every week). Again following Cook et al.’s (1998) precedence, we created a binary dependent variable of had/had not participated in the lottery by collapsing categories together. Some 59.7% of participants had bought lottery tickets at least once in the preceding year, a proportion that is close to the 63.5% of Hong Kong high-school students that Wong and So (2014) report have participated in non-internet gambling.

Five-Factor Model

In view of our Hong Kong sample, we used a cross-culturally applicable refinement of Saucier’s (1994) 40-item lexical five-factor personality measure, the International English Big-Five Mini-Markers (Thompson 2008). This scale was developed to eliminate items emic to North American populations and thereby improve its psychometric properties in English-speaking samples elsewhere. The scale has been successfully used with international samples (Alvergne et al. 2010), and demonstrates high internal consistency reliabilities (Biderman and Reddock 2012). Cronbach’s alphas for our sample are: Extraversion .88; Openness .83; Neuroticism .80; Conscientiousness .85; Agreeableness .80.

Luck Beliefs

We used the Belief in Luck and Luckiness Scale (Thompson and Prendergast 2013). This is applicable to both believers and non-believers in luck, and measures, respectively, Belief in Luck and Belief in Personal Luckiness as discrete, uncorrelated, and unidimensional constructs. As the scale is relatively new and as yet, to our knowledge, unused in gambling research, we conducted a factor analysis to examine if the bi-dimensional luck model Thompson and Prendergast (2013) report was evident for our sample. Table 1 shows the scale produced a clear bi-dimensional solution with low cross-loadings. Our sample’s Cronbach’s alphas for Belief in Luck and Belief in Personal Luckiness dimensions, respectively, are .76 and .89.

Controls

Sex Sex-dependent effects on gambling are reported by Yücel et al. (2015). Zeng and Zhang (2007) find men gamble in lotteries more than women in China, and Lam (2014) finds male undergraduate students in Hong Kong’s neighboring city of Macau are less risk averse than female undergraduates when the values of potential winnings rise. Hence we controlled sex, with our dummy coding males 1.

Age Scholars have found a relationship between age and lottery gambling (Browne and Brown 1994), hence we controlled age.

Confidence of Winning Kwak (2015) finds that perceived higher probability of winning increases some forms of gambling participation. Lottery participation may, therefore, be partly determined by confidence of winning based on appraisal, albeit often highly inaccurate, of winning odds (Prendergast and Thompson 2013). To control for this we used a measure based on two items asking about confidence of winning the Mark-Six Lottery. One asked about confidence of winning the lottery with a ticket whose numbers were selected by participants themselves. The other asked about confidence of winning the lottery with a ticket whose numbers were selected by computer. The items were separated into different sections of the questionnaire to ameliorate possible common method variance between them. Each item was assessed on a 6-point confident/unconfident interval measure, and correlated highly, having a Cronbach’s alpha of .79.

Results

Table 2 shows inter-item correlations.

Table 3 shows hierarchical logistic regression analyses, with continuous variables standardized due to response formats with differing interval measures. Model 1 the baseline regression for controls alone.

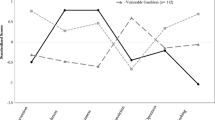

Five-Factor Model

Model 2 enters the five-factor model variables, revealing our hypotheses here are only partially supported. The positive relationship with state-sponsored lottery participation we predicted for Extraversion is supported, as are our predictions for a negative relationship with both Openness and Agreeableness. However, the significant positive relationship we find between Neuroticism and lottery participation means our prediction of no significant relationship is unsupported. Furthermore, our prediction that Conscientiousness would negatively predict state-sponsored lottery gambling is also unsupported as it has no significant effect.

The effects sizes for each of the four significant five-factor model facets, with betas ranging from .19 to −.26 and odds ratios ranging from 0.78 to 1.23, are modest, and the Nagelkerke R2 at .10 is small. Nevertheless, these effect sizes are comparable to those found by Buckle, Dwyer et al. (2013, p. 8–9), MacLaren et al. (2011a, p. 336–337), and Mishra et al. (2010, p. 619) in their studies of personality determinants of gambling. They are also commensurate with what might be anticipated given the broad range of personality, individual difference and socio-economic factors we did not control for but are likely to affect decisions to gamble. While each significant beta is relatively modest, the fact that each maintains and is significant whilst controlling for the others is noteworthy.

Luck Beliefs

Model 3 enters the two luck belief variables alone. While we hypothesized Belief in Luck would be either unrelated significantly to, or negatively related to, lottery gambling, our data reveal Belief in Luck positively predicts state-sponsored lottery gambling relatively strongly. Further, although we predicted a positive relationship between Belief in Personal Luckiness and state-sponsored lottery gambling, our data reveal a significant negative relationship.

With a significant beta of .51 and an odds ratio of 1.67, the relationship of Belief in Luck to state-sponsored lottery gambling is arguably quite strong. Indeed, this effect size is larger than that found in comparable studies of the effect of luck on gambling such as Rogers and Webley (2001, p. 194, tbl. 4), Wu et al. (2012, p. 340–341), and Zhou et al. (2012, p. 386, tbl. 3). While the effect size for Belief in Personal Luckiness is modest, its beta of −.18 and odds ratio of .84 are similar to that for the significant five-factor model facets, and it is again noteworthy that this effect remains significant even in the presence of Belief In Luck’s dominant effect. The Nagelkerke R2 at .14 is still relatively small, but is larger than that for the five-factor model, and, again, commensurate with what might be anticipated given the broad range factors not here modelled that influence the decision to gamble.

Relationship between Luck Beliefs and Five-Factor Model

Model 4 enters both the five-factor model and the luck belief variables together. Both Belief in Luck and Belief in Personal Luckiness remain significant predictors of state-sponsored lottery gambling with little change in the magnitude of their betas. This indicates no support for our hypothesis that basic personality will account for any effects of luck beliefs on state-sponsored lottery gambling. Indeed, the only substantive apparent change to significance and beta magnitude is for Neuroticism, which has a beta reduced close to zero that becomes non-significant.

Comparing Models 2 and 3, luck beliefs alone are seen to double the increase in Nagelkerke R2 from the baseline model compared to the five-factor model alone (ΔNagelkerke R2 = .08 vs ΔNagelkerke R2 = .04). Moreover, comparing Models 2 and 4 indicates that luck beliefs increase Nagelkerke R2 by .07 when added to the five-factor model, whereas comparing Models 3 and 4 shows the five-factor model increases Nagelkerke R2 by only .03. Hence, while the five-factor model does independently partially predict state-sponsored lottery gambling, luck beliefs are a larger and separate personality predictor of state-sponsored lottery gambling.

Discussion

Our findings reveal that state-sponsored lottery gambling is predicted by similar personality profiles to those that predict problem gambling. That Conscientiousness fails to negatively predict and Extraversion positively predicts lottery gambling, suggests that general state-sponsored lottery gamblers may, perhaps, be different from problem gamblers on these personality dimensions. However our finding that Neuroticism positively, and Openness and Agreeableness negatively, predict state-sponsored lottery gambling indicates a pattern of relationships similar to those usually found for problem gambling.

Furthermore, the pattern of relationships we find for luck beliefs is identical to what might be predicted for problem gambling. The strongly significant and large effect found for Belief in Luck is precisely what might be expected with problem gamblers, not non-problem gamblers. That Belief in Personal Luckiness negatively predicts state-sponsored lottery gambling again suggests that state-sponsored lottery gamblers and problem gamblers might be similar. This is because Thompson and Prendergast (2013) suggest Belief in Personal Luckiness is a positive-affect–related construct, supported by Hwang et al.’s (2012) negative relationship between positive affect and problem gambling, and Cummins et al.’s (2009) positive relationship between positive affect and non-problem gambling.

Our findings here might, of course, be confounded by our sample possibly containing some actual problem gamblers. We sought to investigate this possibility by removing problem gamblers from our sample. As a plausible proxy for problem lottery gambling we used lottery gambling frequency. That gambling frequency is a reasonable, albeit not perfect, proxy for problem gambling is suggested by research finding higher gambling frequency is associated with problem gambling generally (Colasante et al. 2014), and problem lottery gambling specifically (Afifi et al. 2014). Accordingly, we removed respondents from our sample who indicated lottery ticket purchasing ‘once or twice every week’. Numbering 40, these most frequent gamblers constituted 4.7% of our original sample of 844, approximately the proportion of problem gamblers found in other Far East student populations, such as Japan, with 4.2% (Kido and Shimazaki 2007), and China, with 6.4% (Tang and Wu 2009). Results of our analyses with frequent lottery gamblers removed (see Appendix Table 4) are nearly identical to our findings for the whole sample, suggesting our results are not obviously confounded by the possibility of problem gamblers being in our sample.

Limitations

Although we have successfully filled a research gap by demonstrating the extent to which state-sponsored lottery gambling is predicted by both the five-factor model and luck beliefs, further research is indicated by both our study’s limitations and findings.

Our sample size (N = 844) was commensurate with that of other researchers in the fields of gambling, luck beliefs and personality. For example, Mackinnon et al. (2016) in their study of the five-factor personality model and gambling motives report a sample of 679. Certainly our sample was adequate to our purposes, affording sufficient power for our analyses given the number of variables we considered. Our sample’s relative homogeneity also allowed partial amelioration of possible educational, socioeconomic, and cultural effects on state-sponsored lottery gambling. However, the limitations of generalizability of findings from an ethnically uniform university student sample needs to borne in mind. That said, the finding of Ye et al. (2012) that Chinese addicted lottery gamblers’ characteristics are broadly similar to those from North America and Europe suggests some degree of international generalizability from our sample would not be inappropriate.

Further, our sample comprised students studying a range of disciplines, hence avoiding the problems of generalizability researchers note in relation specifically to psychology student-only samples that often constitute those used in gambling research (Gainsbury et al. 2014). Nevertheless, further research might use more purposefully heterogeneous samples in order to enable the examination of the potential main, mediation and moderation effects of educational, socioeconomic, and cultural differences on state-sponsored lottery gambling. Additionally, despite our self-report survey method being common to the majority of lottery gambling research, the possibility of differences between what respondents report and what they actually do needs to be kept in mind, as noted by LaPlante et al. (2010) in their review of lottery research.

Conclusions

This paper makes two original contributions to the literature: the first investigation of the five-factor personality model’s relationship to general (ostensibly non-problematic) lottery gambling, and the first application of Thompson and Prendergast’s (2013) bidimensional model of luck beliefs to any form of gambling. We find the bidimensional model of luck beliefs predicts lottery gambling independently from the five-factor personality model, and that its overall effect is greater. Moreover, the broad pattern of relationships we find between luck beliefs, personality, and state-sponsored lottery gambling broadly reflect those that would be predicted, or have been found, in studies relating specifically to problem gambling.

While the precise mechanisms turning general gamblers into problem gamblers are still unknown and need more research, our findings suggest policy makers ought to consider the possibility that the presumably innocuous public policy instrument of state-sponsored and heavily marketed lottery gambling may increase problem gambling and thereby diminish social welfare. In light of this, effort might prudently be given to weighing systematically, on the one hand, the generally advanced public policy benefits of state-sponsored lotteries, such as government revenue raising (Gribbin and Bean 2005), publicly sanctioned individual-level pleasure (Miyazaki et al. 1999), and politically gifted social cohesion effects, against, on the other, its potential social, economic, and public welfare and health disadvantages. Although the proportion of those initially induced into gambling by governments keen to market state-sponsored lotteries is a matter for empirical investigation, the findings of this research hint that the state-sponsorship of lottery gambling could ultimately be generating possibly greater welfare costs to society than any benefits so obtained.

References

Abarbanel, B. L. (2014). Differences in motivational dimensions across gambling frequency, game choice and medium of play in the United Kingdom. International Gambling Studies, 14, 472–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2014.966131.

Afifi, T. O., LaPlante, D. A., Taillieu, T. L., Dowd, D., & Shaffer, H. J. (2014). Gambling involvement: Considering frequency of play and the moderating effects of gender and age. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 12, 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-013-9452-3.

Alvergne, A., Jokela, J., Faurie, C., & Lummaa, V. (2010). Personality and testosterone in men from a high-fertility population. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 840–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.07.006.

André, N. (2006). Good fortune, luck, opportunity and their lack: How do agents perceive them? Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 1461–1472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.10.022.

André, N. (2009). I am not a lucky person: An examination of the dimensionality of beliefs about chance. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25, 473–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-009-9134-z.

Ariyabuddhiphongs, V. (2011). Lottery gambling: A review. Journal of Gambling Studies, 27(1), 15–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-010-9194-0.

Ariyabuddhiphongs, V., & Chanchalermporn, N. (2007). A test of social cognitive theory reciprocal and sequential effects: Hope, superstitious belief and environmental factors among lottery gamblers in Thailand. Journal of Gambling Studies, 23, 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-006-9035-3.

Atkinson, J., Sharp, C., Schmitz, J., & Yaroslavsky, I. (2012). Behavioral activation and inhibition, negative affect, and gambling severity in a sample of young adult college students. Journal of Gambling Studies, 28(3), 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-011-9273-x.

Bagby, R. M., Vachon, D. D., Bulmash, E. L., Toneatto, T., Quilty, L. C., & Costa, P. T. (2007). Pathological gambling and the five-factor model of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(4), 873–880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.011.

Balabanis, G. (2002). The relationship between lottery ticket and scratch-card buying behaviour, personality and other compulsive behaviours. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 2, 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.86.

Balodis, S. R. S., Thomas, A. C., & Moore, S. M. (2014). Sensitivity to reward and punishment: Horse race and EGM gamblers compared. Personality and Individual Differences, 56, 29–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.08.015.

Barnes, G. M., Welte, J. W., Tidwell, M. C. O., & Hoffman, J. H. (2011). Gambling on the lottery: Sociodemographic correlates across the lifespan. Journal of Gambling Studies, 27, 575–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-010-9228-7.

Beckert, J., & Lutter, M. (2009). The inequality of fair play: Lottery gambling and social stratification in Germany. European Sociological Review, 25, 475–488. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcn063.

Biderman, M. D., & Reddock, C. M. (2012). The relationship of scale reliability and validity to respondent inconsistency. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 647–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.012.

Blalock, G., Just, D. R., & Simon, D. H. (2007). Hitting the jackpot or hitting the skids. Entertainment, poverty, and the demand for state lotteries. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 66, 545–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1536-7150.2007.00526.x.

Bogg, T., & Roberts, B. W. (2004). Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychological Bulletin, 130(6), 887–919. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.887.

Borch, A. (2012). Gambling in the news and the revelation of market power: The case of Norway. International Gambling Studies, 12, 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2011.616907.

Browne, B., & Brown, D. (1994). Predictors of lottery gambling among American college students. Journal of Social Psychology, 134, 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1994.9711738.

Buckle, J. L., Dwyer, S. C., Duffy, J., Brown, K. L., & Pickett, N. D. (2013). Personality factors associated with problem gambling behavior in university students. Journal of Gambling Issues, 28, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2013.28.19.

Buelow, M. T., & Suhr, J. A. (2013). Personality characteristics and state mood influence individual deck selections on the Iowa gambling task. Personality and Individual Differences, 54, 593–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.019.

Carver, A. B., & McCarty, J. A. (2013). Personality and psychographics of three types of gamblers in the United States. International Gambling Studies, 13, 338–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2013.819933.

Chen, V. C. H., Stewart, R., & Lee, C. T. C. (2012). Weekly lottery sales volume and suicide numbers: A time series analysis on national data from Taiwan. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47, 1055–1059. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0410-8.

Chiu, J., & Storm, L. (2010). Personality, perceived luck and gambling attitudes as predictors of gambling involvement. Journal of Gambling Studies, 26, 205–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-009-9160-x.

Colasante, E., Gori, M., Bastiani, L., Scalese, M., Siciliano, V., & Molinaro, S. (2014). Italian adolescent gambling behaviour: Psychometric evaluation of the south oaks gambling screen—Revised for adolescents (SOGS-RA) among a sample of Italian students. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-013-9385-6.

Cook, M., McHenry, R., & Leigh, V. (1998). Personality and the national lottery. Personality and Individual Differences, 25, 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00060-9.

Cummins, L. F., Nadorff, M. R., & Kelly, A. E. (2009). Winning and positive affect can lead to reckless gambling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23, 287–294. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014783.

Cyders, M. A., & Smith, G. T. (2008). Clarifying the role of personality dispositions in risk for increased gambling behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 503–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.06.002.

Darke, P. R., & Freedman, J. L. (1997). The belief in good luck scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 31, 486–511. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1997.2197.

Demaree, H. A., DeDonno, M. A., Burns, K. J., & Everhart, D. E. (2008). You bet: How personality differences affect risk-taking preferences. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 1484–1494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.01.005.

Digman, J. M. (1990). Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology, 41, 417–440. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.41.020190.002221.

Dorn, A. J., Dorn, D., & Sengmueller, P. (2015). Trading as gambling. Management Science, 61, 2376–2393. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1979.

Felsher, J. R., Derevensky, J. L., & Gupta, R. (2004). Lottery playing amongst youth: Implications for prevention and social policy. Journal of Gambling Studies, 20, 127–153. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOGS.0000022306.72513.7c.

Fielding, H. (2004). The lottery. Kessinger: Whitefish, Montana.

Fortune, E. E., & Goodie, A. S. (2012). Cognitive distortions as a component and treatment focus of pathological gambling: A review. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26, 298–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026422.

Friedland, N. (1998). Games of luck and games of chance: The effect of luck- versus chance-orientation on gambling decisions. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 11, 161–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0771(199809)11:3<161::AID-BDM296>3.0.CO;2-S.

Gainsbury, S. M., Russell, A., & Blaszczynski, A. (2014). Are psychology university student gamblers representative of non-university students and general gamblers? A comparative analysis. Journal of Gambling Studies, 30(1), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-012-9334-9.

Gibson, B., & Sanbonmatsu, D. M. (2004). Optimism, pessimism, and gambling: The downside of optimism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203259929.

Goldberg, L. R. (1993). The structure of phenotypic personality-traits. American Psychologist, 48, 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.1.26.

Gribbin, D. W., & Bean, J. J. (2005). Adoption of state lotteries in the United States, with a closer look at Illinois. The Independent Review, 10, 351–364.

Griffiths, M. D., & Wood, R. T. A. (2001). The psychology of lottery gambling. International Gambling Studies, 1, 27–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459800108732286.

Guryan, J., & Kearney, M. S. (2010). Is lottery gambling addictive? American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2, 90–110. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.2.3.90.

Hansen, A., Miyazaki, A., & Sprott, D. (2000). The tax incidence of lotteries: Evidence from five states. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 34(2), 182–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2000.tb00090.x.

Horváth, C., & Paap, R. (2012). The effect of recessions on gambling expenditures. Journal of Gambling Studies, 28, 703–717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-011-9282-9.

Humphreys, B. R., & Perez, L. (2013). Syndicated play in lottery games. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 45, 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2013.05.010.

Hwang, J. Y., Shin, Y. C., Lim, S. W., Park, H. Y., Shin, N. Y., Jang, J. H., & Kwon, J. S. (2012). Multidimensional comparison of personality characteristics of the big five model, impulsiveness, and affect in pathological gambling and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Gambling Studies, 28, 351–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-011-9269-6.

Jaunky, V. C., & Ramchurn, B. (2014). Consumer behaviour in the scratch card market: A double-hurdle approach. International Gambling Studies, 14, 96–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2013.855251.

Kaizeler, M. J., Faustino, H. C., & Marques, R. (2014). The determinants of lottery sales in Portugal. Journal of Gambling Studies, 30, 729–736. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-013-9387-4.

Kido, M., & Shimazaki, T. (2007). Reliability and validity of the modified Japanese version of the south oaks gambling screen (SOGS). Japanese Journal of Psychology, 77, 547–552. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.77.547.

Kwak, D. H. (2015). The overestimation phenomenon in a skill-based gaming context: The case of march madness pools. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-015-9520-7.

Lam, D. (2014). Gender differences in risk aversion among Chinese university students. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-014-9492-z.

Lang, K., & Omori, M. (2009). Can demographic variables predict lottery and pari-mutuel losses? An empirical investigation. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25, 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-009-9122-3.

LaPlante, D. A., Gray, H. M., Bosworth, L., & Shaffer, H. J. (2010). Thirty years of lottery public health research: Methodological strategies and trends. Journal of Gambling Studies, 26, 301–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-010-9185-1.

Li, H., Mao, L., Zhang, J. J., Wu, Y., Li, A., & Chen, J. (2012). Dimensions of problem gambling behavior associated with purchasing sports lottery. Journal of Gambling Studies, 28, 47–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-011-9243-3.

Mackinnon, S. P., Lambe, L., & Stewart, S. H. (2016). Relations of five-factor personality domains to gambling motives in emerging adult gamblers: A longitudinal study. Journal of Gambling Issues, 34, 179–200. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2016.34.10.

MacLaren, V. V., Best, L. A., Dixon, M. J., & Harrigan, K. A. (2011a). Problem gambling and the five factor model in university students. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 335–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.10.011.

MacLaren, V. V., Fugelsang, J. A., Harrigan, K. A., & Dixon, M. J. (2011b). The personality of pathological gamblers: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 1057–1067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.02.002.

MacLaren, V. V., Fugelsang, J. A., Harrigan, K. A., & Dixon, M. J. (2012). Effects of impulsivity, reinforcement sensitivity, and cognitive style on pathological gambling symptoms among frequent slot machine players. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 390–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.044.

Malouff, J. M., Thorsteinsson, E. B., & Schutte, N. S. (2006). The five-factor model of personality and smoking: A meta-analysis. Journal of Drug Education, 36, 47–58. https://doi.org/10.2190/9EP8-17P8-EKG7-66AD.

Maltby, J., Day, L., Gill, P., Colley, A., & Wood, A. M. (2008). Beliefs around luck: Confirming the empirical conceptualization of beliefs around luck and the development of the Darke and Freedman beliefs around luck scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 655–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.07.010.

McInnes, A., Hodgins, D. C., & Holub, A. (2014). The gambling cognitions inventory: Scale development and psychometric validation with problem and pathological gamblers. International Gambling Studies, 14, 410–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2014.923483.

McMullan, J. L., & Miller, D. (2009). Wins, winning and winners: The commercial advertising of lottery gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25, 273–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-009-9120-5.

Miller, J. D., MacKillop, J., Fortune, E. E., Maples, J., Lance, C. E., Campbell, W. K., & Goodie, A. S. (2013). Personality correlates of pathological gambling derived from big three and big five personality models. Psychiatry Research, 206(1), 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.042.

Mishra, S., Lalumière, M. L., & Williams, R. J. (2010). Gambling as a form of risk-taking: Individual differences in personality, behavioral preferences for risk, and risk-accepting attitudes. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 616–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.032.

Miyazaki, A. D., Langenderfer, J., & Sprott, D. E. (1999). Government-sponsored lotteries: Exploring purchase and nonpurchase motivations. Psychology & Marketing, 16(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199901)16:1<1::AID-MAR1>3.0.CO;2-W.

Moghaddam, J. F., Campos, M. D., Myo, C., Reid, R. C., & Fong, T. W. (2014). A longitudinal examination of depression among gambling inpatients. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-014-9518-6.

Moore, S. M., Thomas, A. C., Kale, S., Spence, M., Zlatevska, N., Staiger, P. K., … Kyrios, M. (2013). Problem gambling among international and domestic university students in Australia: Who is at risk? Journal of Gambling Studies, 29(2), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-012-9309-x.

Myrseth, H., Pallesen, S., Molde, H., Johnsen, B. H., & Lorvik, I. M. (2009). Personality factors as predictors of pathological gambling. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 933–937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.018.

Öner-Özkan, B. (2003). Revised form of the belief in good luck scale in a Turkish sample. Psychological Reports, 93(2), 585–594. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.2003.93.2.585.

Perez, L., & Humphreys, B. R. (2011). The income elasticity of lottery: New evidence from micro data. Public Finance Review, 39, 551–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/1091142111403620.

Phillips, J. G., & Ogeil, R. P. (2011). Decisional styles and risk of problem drinking or gambling. Personality and Individual Differences, 51, 521–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.05.012.

Phillips, J. G., Butt, S., & Blaszczynski, A. (2006). Personality and self-reported use of mobile phones for games. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 9, 753–758. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.753.

Pravichai, S., & Ariyabuddhiphongs, V. (2014). Superstitious beliefs and problem gambling among Thai lottery gamblers: The mediation effects of number search and gambling intensity. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-014-9517-7.

Prendergast, G. P., & Thompson, E. R. (2008). Sales promotion strategies and belief in luck. Psychology & Marketing, 25, 1043–1062. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20251.

Rodgers, B., Caldwell, T. M., & Butterworth, P. (2009). Measuring gambling participation. Addiction, 104, 1065–1069. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02412.x.

Rogers, P., & Webley, P. (2001). “It could be us!”: Cognitive and social psychological factors in UK National Lottery play. Applied Psychology, 50, 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00053.

Saucier, G. (1994). Mini-Markers: A brief version of Goldberg’s unipolar big-five markers. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63, 506–516. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6303_8.

Steenbergh, T. A., Meyers, A. W., May, R. K., & Whelan, J. P. (2002). Development and validation of the gamblers’ beliefs questionnaire. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 16(2), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.16.2.143.

Sundqvist, K., & Wennberg, P. (2015). Risk gambling and personality: Results from a representative Swedish sample. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31, 1287–1295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-014-9473-2.

Tang, C., & Wu, A. S. (2009). Screening for college problem gambling in Chinese societies: Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the south oaks gambling screen (C-SOGS). International Gambling Studies, 9(3), 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459790903348194.

Thege, B. K., & Hodgins, D. C. (2014). The ‘light drugs’ of gambling? Non-problematic gambling activities of pathological gamblers. International Gambling Studies, 14, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2013.839732.

Thompson, E. R. (2008). Development and validation of an international English big-five mini-markers. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 542–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.06.013.

Prendergast, G. P, & Thompson, E. R. (2013). Rational and irrational influences on lucky draw participation. International Journal of Advertising, 32, 85–100. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-32-1-085-100.

Thompson, E. R., & Prendergast, G. P. (2013). Belief in luck and luckiness: Conceptual clarification and new measure validation. Personality and Individual Differences, 54, 501–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.10.027.

Trousdale, M. A., & Dunn, R. A. (2014). Demand for lottery gambling: Evaluating price sensitivity within a portfolio of lottery games? National Tax Journal, 67, 595–619.

Wardle, H., Moody, A., Griffiths, M. D., Orford, J., & Volberg, R. (2011). Defining the online gambler and patterns of behaviour integration: Evidence from the British gambling prevalence survey 2010. International Gambling Studies, 11, 339–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2011.628684.

Watt, C., & Nagtegaal, M. (2000). Luck in action? Belief in good luck, psi-mediated instrumental response, and games of chance. The Journal of Parapsychology, 64(1), 33–52.

Wohl, M. J. A., & Enzle, M. E. (2002). The deployment of personal luck: Sympathetic magic and illusory control in games of pure chance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1388–1397. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616702236870.

Wohl, M. J. A., & Enzle, M. E. (2003). The effects of near wins and near losses on self-perceived personal luck and subsequent gambling behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 184–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1031(02)00525-5.

Wohl, M. J. A., Young, M. M., & Hart, K. E. (2005). Untreated young gamblers with game-specific problems: Self-concept involving luck, gambling ecology and delay in seeking professional treatment. Addiction Research & Theory, 13, 445–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066350500168444.

Wong, I. L. K., & So, E. M. T. (2014). Internet gambling among high school students in Hong Kong. Journal of Gambling Studies, 30, 565–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-013-9413-6.

Wu, A. M. S., Tao, V. Y. K., Tong, K. K., & Cheung, S. F. (2012). Psychometric evaluation of the inventory of gambling motives, attitudes and behaviors (GMAB) among Chinese gamblers. International Gambling Studies, 12, 331–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2012.678273.

Ye, Y., Gao, W., Wang, Y., & Luo, J. (2012). Comparison of the addiction levels, sociodemographics and buying behaviours of three main types of lottery buyers in China. Addiction Research & Theory, 20, 307–316. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2011.629764.

Young, M. J., Chen, N., & Morris, M. W. (2009). Belief in stable and fleeting luck and achievement motivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(2), 150–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.02.009.

Yücel, M., Whittle, S., Youssef, G. J., Kashyap, H., Simmons, J. G., Schwartz, O., et al. (2015). The influence of sex, temperament, risk-taking and mental health on the emergence of gambling: A longitudinal study of young people. International Gambling Studies, 15, 108–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2014.1000356.

Zeng, Z., & Zhang, D. (2007). A profile of lottery players in Guangzhou, China. International Gambling Studies, 7, 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459790701601430.

Zhou, K., Tang, H., Sun, Y., Huang, G., Rao, L., Liang, Z., & Li, S. (2012). Belief in luck or in skill: Which locks people into gambling? Journal of Gambling Studies, 28, 379–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-011-9263-z.

Zuckerman, M., & Kuhlman, D. M. (2000). Personality and risk-taking: Common biosocial factors. Journal of Personality, 68, 999–1029. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00124.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved with all aspects of the preparation of this study, with the exception of data collection towards which Gerard Dericks did not contribute. All authors had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the following: the University of Bath’s Code of Good Practice In Research Integrity (http://www.bath.ac.uk/research/governance/ethics/%20, 2016) and University of Bath Research Ethics Committee (University of Bath, 2016, ERIA1 Approval, 20/07/16); the Human (non-clinical) Research Ethics Panel, Hong Kong Baptist University Research Ethics Committee; and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

The conduct, resourcing and reporting of this research neither entailed nor entails any conflicts of interest. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the following: the [Name of Institute 1]‘s Code of Good Practice In Research Integrity ([Internet Link to Institute 1’s Code of Practice]) and [Name of Institute 1] Research Ethics Committee ([Name of Institute 1], 2016, ERIA1 Approval, 20/07/16); the Human (non-clinical) Research Ethics Panel, [Name of Institute 2] Research Ethics Committee; and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

The conduct, resourcing and reporting of this research neither entailed nor entails any conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Thompson, E.R., Prendergast, G.P. & Dericks, G.H. Personality, Luck Beliefs, and (Non-?) Problem Lottery Gambling. Applied Research Quality Life 16, 703–722 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09791-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09791-4