Abstract

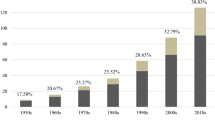

Within the development literature three accords seem to have taken place regarding poverty measurement. These relate to the relative or absolute measurement of poverty, the monetary versus basic needs measurement, and the existence of an international poverty line. In this paper, all three of these accords are challenged from an evolutionary perspective. A framework is presented to show how the poverty line (as well as the nature and characteristics of poverty) evolve as countries go through the process of changing consumption and production patterns that increases average income, i.e., transformational growth. Based on this framework, an answer to the problem of how to compare poverty rates through long periods of time is developed. It results in an absolute poverty line (rather than a relative one), which changes through time. This approach is shown to be better (because it is not mechanical) than the income-elasticity of the poverty line for inter-temporal comparisons. It is not mechanical because the poverty line is not adjusted by the change in average income but on the socially determined, evolving, acceptable minima to participate in society. It is also found to avoid the limitations of the currently used "international poverty lines.“ Finally, a similar approach is used to develop a method of adjusting the measurement of poverty based on basic needs, i.e., using a matrix of social deprivations rather than a monetary poverty line. This is done using the methodology developed by UNICEF, the University of Bristol, and the London School of Economics to measure child poverty based on deprivation of rights, which constitute poverty. This method has been applied in over 70 countries world-wide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

However, Marshall (1890) had an evolutionary perspective and admired Darwin – even if his modelling and the tradition that followed from it are static.

Ranging from industrial change (e.g. Nelson 1995, Nelson 1981, Nelson and Winter 1982) to institutions (e.g. Hodgson 1993, Hodgson 2004, Hodgson 2006) as well as more general treatises and discussions about the nature of evolutionary economics (e.g. Hodgson 2013, Hodgson and Knudsen 2010, Louca and Perlman 2000 and Witt 2003, among many others).

This is similar to the approach taken by Ellis et al. (2012) regarding adolescent risky behaviour and Wilson et al. (mimeo) regarding childhood education.

Sometimes this is just the cost of a minimum dietary intake or it also includes other items (Desai 1986). The major exception is among European countries that use a relative poverty approach, but this experience is usually not included in the development literature.

The so-called “dollar a day” would be an example of an absolute poverty line, were it not that it is not actually such a measurement as it is explained below.

These could be societies, institutions, language, production techniques, etc.

This seems the view he prefers. Although Witt does not dwell on this, this approach is similar to the ideas and models of self-organization of open systems in Thermodynamics (Prigogine 1980) which have been “exported” to other disciplines (Prigogine and Stengers 1978) and have been used in economics by, among others, Anderson et al. 1988, Argyrous et al. 2004, Arthur 2006, Dosi et al. 1988, and Lesourne and Orlean 1998. For the notion of open systems in the social sciences, Bhaskar (1989) can be consulted.

At least three versions of equilibrium can be found among traditional economists (clearly these three notions are inter-related): a preferred position, market clearing, and convergence to a steady state. The approach expounded here confronts all three types of equilibrium.

Given that Smith was writing in the XVIIIth Century, the gender-insensitive language could be excused.

Summarized in the following formula (Foster et al. 1984):

$$ FG{T}_{\alpha }=\frac{1}{N}{\displaystyle \sum_{i=1}^H\left(\frac{z-{y}_i}{z}\right)\alpha } $$Where z is the agreed upon poverty line, N is the number of people in an economy, H is the number of poor (those with incomes at or below z), y i are individual incomes and α is the “sensitivity” parameter.

Unfortunately, this is done with a “pure number” which is very difficult to interpret intuitively -unlike the incidence of poverty which is a proportion of the population.

An interesting application of the combination between monetary poverty and basic needs allowed for the analysis of the experience of the “new poor” in the context of economic crises (Minujin 1995).

Even the so-called dollar a day line is adjusted. That is why it used to be 1.08 and now it is 1.25 U$PPP.

As total income is 75, average income 15 and half of it is 7.5 at T1. Similar calculations establish the relative poverty to be 20 at T2.

Lest it be assumed this is a hypothetical curiosum, it may be interesting to look at the recent European data. Although the focus of this article is on developing countries, as it was mentioned above, European countries use the relative poverty line. Of course this means that the exercise cannot be performed as in the example as there is no trend in absolute poverty to compare. Nevertheless, the trend of relative poverty in the wake of the financial crisis is illustrative. Plotting real GDP growth rates (averaged over 2008–10) against changes in relative poverty (comparing the average between 2001 and 2005 against the average for the period 2008–10) shows no relationship whatsoever. This is not surprising as the result is consistent with evidence about the lack of correlation between real average per capita changes and absolute poverty among developing countries. It is more striking to compare what has happened among the countries hardest hit by the crisis. These are the countries where there were at least two years of negative growth and an average decline higher than 1.5 % per year during 2008–2010. The countries are (the absolute difference comparing the average relative poverty between 2001 and 2005 against the average value between 2008 and2010 is in parenthesis for each country): Denmark (+1.63), Greece (−0.08), Iceland (+0.48), Ireland (−5.29), and Italy (−0.57). While poverty increased in some countries (e.g. Denmark), it stayed essentially level (e.g. Greece and Iceland), and actually declined in another one (Ireland). This occurred in a context of generalized contraction with unemployment increasing around 33 % (Italy), 50 % (Greece), 200 % (Ireland) and 230 % (Iceland) and countless qualitative evidence of penury, increasing homelessness, etc. However, given that middle class and rich households also saw their incomes decline, no increase in (relative) poverty was observed. Comparing changes in the income quintile share ratio (between the top and bottom quintiles) to analyse changes in income distribution, whether considering absolute (or percentage) differences between 2008 and 2010 or the standard deviation around the mean for the same period, Denmark (where relative poverty increased) shows the most markedly worsening income distribution while in the other countries it only changed very little. The fact that relative poverty did increase in some countries does not invalidate the point: it is possible (not a certainty or an automatic relationship) that when all incomes rise and fall, the relative poverty fails to capture what is happening to those at the lowest end of the scale in terms of whether they can or cannot afford a basic set of goods to allow them not to be poor in the sense of sustaining a minimum standard of living. All the data used in this footnote is from Eurostat, other periods and tests were used to assess the robustness of these results and the conclusions still hold.

Although not central to the argument of this paper, it is interesting to note that there is a right to a minimum standard of living enshrined in many international human rights conventions (and first established in the 1948 Declaration of Human Rights) but not to an equal or even or egalitarian or equitable income distribution.

As mentioned above the issue of international and inter-temporal comparisons have fundamental similarities. These will be brought up in the subsequent section too.

Obviously the ten years interval is arbitrary. It does have the virtue that it is not too frequent nor too long a period. National Statistical Offices are the ones in charge of measuring poverty and estimating poverty lines so they should lead their periodic adjustment. Ideally the process of re-calculating the poverty line should include government statistics (e.g. on aggregate income, the level of consumption, etc.), household surveys (to understand their consumption patterns), input–output matrices (to address the emergence of new goods and services and their weight in the economy), and participatory processes to capture which goods and services are necessities morally accepted by social habit as minima not to be poor. For the latter, the Consensual Approach (Mack et al. 1985) could be used as it is considered a practical way to establish what should be included in the measurement of poverty (Rio Group and Compendium of Best Practices in Poverty Measurement 2006) and it has been applied in many countries throughout the world. It is important to point out that (as it is discussed below) establishing poverty lines impacts fiscal accounts (e.g. through establishing eligibility criteria for government programmes and subsidies). As a result, establishing poverty lines is not purely a technical issues but one with political implications, which is a potential limitation both of the approach and the solutions proposed in this paper.

In addition, the range for arbitrariness is limited as most members of society know what constitutes (or not) a state of poverty and who among the members of society are poor (as discussed in Lineages of Poverty Measurement section).

In this context, international institutions could corroborate that technocrats, academics, and politicians, do interpret what the minima are in each particular society. The Consensual Approach mentioned above would be a way to address this risk.

Thus, the weight could be inversely proportional to the proportion of the population consuming the good or service as suggested by Hancioglu (2005) to classify households according to their wealth.

This, from a practical implementation point of view would be similar to class-action suits or settlements of historical wrongs or reparations.

The discussion in this paragraph takes as given the concept that only those below the poverty line were supposed to receive the subsidy. This is not an endorsement of this type of social policy interventions. It is only accepted because it is a very common way to allocate resources. However, it has to be remembered that many people, even if their income is above the poverty line most probably deserve the subsidy too.

As used, for example by Don Quixote’s Sancho Panza when he ruled the island of Barataria.

Admittedly, these proposals seem simple but may be politically contestable and difficult to implement.

It may useful to remember here the thrust of the argument of this paper. It is the absolute poverty line (the minimum basket required in a particular society) that changes as the economy evolves through long periods of time.

This does not imply that economic growth may have costs too (e.g. environmental, social disruption, decrease in happiness, etc.) which are not captured by traditional statistics. These important topics, for reasons of space, cannot be dealt with in this paper.

Deaton and Paxton 1997, use various levels and adjustments of monetary poverty lines to estimate child poverty.

The study was commissioned by UNICEF to the London School of Economics and the University of Bristol. The seven dimensions were: water, sanitation, housing, education, health, nutrition, and access to information. Severe, rather than moderate, deprivation thresholds were used in order to avoid the criticism of inflating the plight of children. For instance, for education, the threshold was that the child had never been to a formal school; for nutrition, the threshold was to be three standard deviations below the international norm for all three anthropometric measures (under-weight, stunting and wasting).

It has to be emphasized that the weights apply strictly to the change though time of the old and new indicators. Weights are not applied to aggregate across dimensions because they refer to rights and it is not possible, conceptually, to weigh them (i.e. to say that education is twice or half as important as health). While it is possible to do so (from a mathematical or formal stance, as the data in households surveys allow this) it would be inappropriate.

As in the case of monetary poverty, the information comes from household surveys. At each point in time, different people are interviewed. These are not longitudinal studies.

A more elaborate case could be presented using different indicators within each dimension as described in the text. It would not affect the main arguments being made here.

References

Alkire, S., & Foster, J. (2009). “Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement”, Working Paper, N° 32, Oxford.

Anderson, P. W., Arrow, K. J., & Pines, D. (Eds.). (1988). The economy as an evolving complex system: the proceedings of the evolutionary paths of the global economy workshop. Reading: Addison-Wesley Pu.Co.

Argyrous, G., Forstater, M., & Mongiovi, G. (Eds.). (2004). Growth, distribution, and effective demand: alternatives to economic orthodoxy: essays in honor of Edward Nell. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe.

Arthur, W. B. (2006). “Out-of-Equilibrium Economics and Agent-based Modeling”, Handbook of Computational Economics Volume 2. Agent-based Computational Economics, Edited by Leigh Tesfatsion and Kenneth L. Judd.

Bhaskar, R. (1989). Reclaiming Reality: A Critical Introduction to Contemporary Philosophy, Verso.

Boltvinik, J. (1998). Poverty measurement methods— an overview. New York: UNDP.

Booth, C. (1902). Life and labour of the people in London (Vol. 1, p. 1902). London: Macmillan.

CEPAL-UNICEF (2010). La Pobreza Infantil en América Latina y el Caribe, Santiago de Chile.

Chakravarty, 5. (1982). Alternative Approaches to a Theory of Economic Growth: Marx, Marshall and Schumpeter, Oriental Longman.

Chambers, R. (1997). Whose reality counts? putting the first last. London: Intermediate Technology Publications.

Chambers, R. (2007). Who Counts? The Quiet Revolution of Participation and Numbers, IDS Working Paper 296

Citro, C. F., & Michael, R. T. (Eds.). (1995). Measuring Poverty: A New Approach, Washington. D.C.: National Academy Press.

Deaton, A. (2003). “How to Monitor Poverty for the Millennium Development Goals,” Journal of Human Development. Vol. 4, No. 3, November 2003.

Deaton, A. (2010). "Price indexes, inequality, and the measurement of world poverty,". American Economic Review, American Economic Association, 100(1), 5–34.

Deaton, A., Paxton, C. (1997). Poverty among children and the elderly in developing countries, Princeton.

Delamonica, E., & Minujin, A. (2007). Prevalence, depth and severity of children in poverty. Social Indicators Research, 82, 361–374.

Desai, M. (1986). Drawing the line: on defining the poverty threshold. In P. Golding (Ed.), Excluding the poor (p. 1986). London: Child Poverty Action Group.

Dosi, G., Freeman, C., Nelson, R., Silverberg, G., & Soete, L. (Eds.). (1988). Technical change and economic theory. London: Printer.

Ellis, B. J., Del Giudice, M., Dishion, T. J., Figueredo, A. J., Gray, P., Griskevicius, V., et al. (2012). “The evolutionary basis of risky adolescent behavior: implications for science, policy, and practice”. Developmental Psychology, 48(3), 598–623.

Foster, J., Greer, J. & Thorbecke E. (1984). ‘A Class of Decomposable Poverty Measures’. Econometrica, 42.

Gordon, D., Nandy, S., Pantazis, C., Pemberton, S., & Townsend, P. (2003). Child poverty in the developing world. Bristol: The Policy Press.

Hancioglu, A. (2005). Performance of alternative approaches for identifying the relatively poor and linkages to reproductive health. In S. Lerner & E. Vilquin (Eds.), Reproductive health, unmet needs and poverty: issues of access and quality of services. Paris: Committee for International Cooperation in National Research in Demography.

Hodgson, G. M. (1993). Economics and Evolution: Bringing Life Back into Economics, Polity Press, Cambridge and University of Michigan Press.

Hodgson, G. M. (2004). The evolution of institutional economics: agency, structure and Darwinism in american institutionalism. London: Routledge.

Hodgson, G. M. (2006). Economics in the shadows of Darwin and Marx: essays on institutional and evolutionary themes. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Hodgson, G. M. (2013). From Pleasure Machines to Moral communities: An Evolutionary Economics without Homo Economicus, University of Chicago Press.

Hodgson, G. M. & Knudsen, T. (2010). Darwin’s Conjecture: The search for General Principles of Social and Economic evolution, University of Chicago Press.

Hunt, P., Osmani, S., & Manfred, N. (2002). Draft guidelines: a human rights approach to poverty reduction strategies. Geneva: Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

ILO. (1976). Employment, growth and basic needs. Geneva: A One-World Problem.

Jones, N., & Sumner, A. (2011). Child Poverty, Evidence, and Policy: Mainstreaming Children in International Development. Bristol: Policy Press.

Laderchi, C., Saith, R., Steward, F. (2003). “Does it matter that we don’t agree on the definition of poverty? Acomparison of four approaches”, en Working Paper Number 107, Queen Elizabeth House, Universidad de Oxford.

Lesourne, J., & Orlean, A. (Eds.). (1998). Advances in self-organization and evolutionary economics. Paris: Economica.

Lipton, M., & Ravallion, M. (1994). "Poverty and policy". In J. Behrman & T. N. Srinivasan (Eds.), Handbook of development economics. North-Holland: Amsterdam.

Lister, R. (2004). Poverty. Londres: Polity Press.

Louca, F., Perlman M. (ed) (2000). Is Economics an Evolutionary Science?, Edward Elgar, 2000.

Lyytikäinen, K., Jones, N., Huttly, S., & Abramsky, T. (2006). Childhood poverty, basic services and comulative disadvantage: An international comparative analysis, young lives working paper No. 33. London: Young Lives and Save the Children.

Mack, J., & Lansley, S. (1985). Poor Britain. London: Allen and Unwin.

Marshall, A. (1890). Principles of economics: An introductory volume. London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd.

Marx, Karl (1867). Capital: Volume 1: A Critique of Political Economy. London, England: Penguin Classics 1990.

Minujin, A. (1995). “Squeezed: the middle class in Latin America”, Environment and Urbanization.

Minujin, A., & Nancy, S. (Eds.). (2012). Global child poverty and well-being: measurement, concepts, policy and action. Bristol: Policy Press.

Nandy, S., & Gordon D. (2009). Children Living in Squalor: Shelter, Water and Sanitation Deprivations in Developing Countries. Children, Youth and Environments (19)(2): 202–228.

Nell, E. (1992). Transformational growth and effective demand. NY: NYU Press.

Nell, E. (1998a). (editor) Studies in Transformational Growth.

Nell, E. (1998b). The General Theory of Transformational Growth

Nelson, R. (1981). Research on productivity growth and productivity differences : dead ends and new departures. Journal of Economic Literature, 19, 1029–64.

Nelson, R. (1995). Recent evolutionary theorizing about economic change. Journal of Economic Literature, 33, 48–90.

Nelson, R., & Winter, S. (1982). An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change, Harvard University Press.

Noble, M., Ratcliffe, A., & Wright, G. (2004). Conceptualizing, defining and measuring poverty in south africa: An argument for a consensual approach. Oxford: Centre for the Analysis of South African Policy.

Noble, M., Wright, G., & Cluver, L. (2006). Developing a child-focused and multidimensional model of child poverty for South Africa. Journal of Children and Poverty, 12(1), 39–53.

Notten, G., Makosso, B., & Mpoue, A. (2008). “La pauvreté multidimensionelle des enfants et des femmes en République du Congo“. Brazzaville: UNICEF. 2008.

Nussbaum, M. (2001). Women and Human Development. The Capabilities Approach, Cambridge University Press.

Orshansky, M. (1965). "Counting the Poor: Another look at the poverty profile", Social Security Bulletin, 28.

Pogge, T., & Reddy S. G. (2006). "Unknown: Extent, Distribution and Trend of Global Income Poverty,” Economic and Political Weekly Vol. 41, No. 22 Jun. 3–9, 2006), pp. 2241–2247.

Prigogine, I. (1980). From Being to Becoming, Freemand & Co.

Prigogine, I., & Stengers, I. (1978). La nouvelle alliance. Paris: Folio.

Pritchett, L. (2006). Who is Not Poor? Dreaming of a World Truly Free of Poverty, World Bank Research Observer, (Spring 2006) 21 (1): 1–23.

Reddy, S. G., & Minoiu, C. (2007). "Has poverty really fallen?". Review of Income and Wealth, International Association for Research in Income and Wealth, 53(3), 484–502.

Ricardo, D. (1821). On the principles of political economy and taxation. London: John Murray, Albermale-Street.

Rio Group (2006). Compendium of Best Practices in Poverty Measurement, Rio de Janeiro: Expert Group on Poverty Statistics, IBGE.

Rowntree, Seebohm (1902). Poverty: A Study of Town Life, London.

Schumpeter, J. (1934). The theory of economic development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sen, A. K. (1982). Choice, Welfare and Measurement, Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. K. (1983), ‘Poor, Relatively Speaking,’ Oxford Economic Papers, No. 37, pp. 669–76.

Sen, A. K. (1985). Commodities and Capabilities, Oxford University Press.

Smith, A. (1776). An Inquiry in the nature and causes of the wealth of nations.

Streeten, P., et al. (1981). First things first: meeting basic needs in developing countries. New York: Oxford University Press.

Townsend, Peter (1985), ‘A Sociological Approach to the Measurement of Poverty—A Rejoinder to Professor Amartya Sen,’ Oxford Economic Papers, Vol. 37, pp. 659–68; extracts reproduced in Peter Townsend 1993, pp. 126–136.

UNDP (2010). Human Development Report, New York.

UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre (2012). ‘Measuring Child Poverty: New league tables of child poverty in the world’s rich countries’, Innocenti Report Card 10, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Florence.

Veblen, T. (1898). Why is economics not an evolutionary science?”. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 12(4), 373–397. ISSN 0033–5533.

Wilson, D. S. & J. Gowdy (2013). “Evolution as a general theoretical framework for economics and public policy”, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, Volume 90, Supplement.

Witt, U. (2003). The evolving economy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Witt, U. (2008). What is specific about evolutionary economics? Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 18, 547–575.

Wolff, E. (2007). “Recent Trends in Household Wealth in the United States: Rising Debt and the Middle-Class Squeeze.” Working Paper No. 502. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College.

Wolff, E. (2010). “Recent Trends in Household Wealth in the United States: Rising Debt and the Middle-Class Squeeze—an Update to 2007.” Working Paper No. 589. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College.

World Bank. (1990). World development report: poverty. Washington DC: World Bank.

Wratten, E. (1995). “Conceptualizing urban poverty”, Environment and Urbanization, Vol. 7, N.° 1, April, 1995.

Acknowledgement

Alberto Minujin, Jerry Lieberman, Gin Kohl Lieberman, Edward Nell, Ignacio Perrotini, Matias Vernengo, David Sloan Wilson, Ismael Cid Martinez, Victoria Colamarco, Lyana Mahmoudi, and two anonymous referees provided very helpful comments. I thank them for their suggestions, encouragement and support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Annex I Hypothetical Example of Child Poverty Evolution with Two Dimensions and Changing Thresholds

Annex I Hypothetical Example of Child Poverty Evolution with Two Dimensions and Changing Thresholds

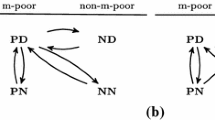

In recent years, several authors have worked on formalizing and providing rigor to the way multidimensional poverty is calculated. Different ways exist to include in one general formula the possibility of estimating the incidence, depth and severity of poverty as well as allowing for endogenous determination of thresholds (at what level of each dimension should the person be considered lacking that dimension in order to be considered poor) and number of dimensions which have to fall below a certain threshold in order to be considered poor.

Nevertheless, all of these formulae, under certain parameters, provide basically the same results. What is important to understand the results of multidimensional poverty estimates is that the estimate is neither the sum nor the average of the individual deprivations. It is a composite. The following examples may help clarify this point.

Suppose there are five children (A through E in the table below) and four dimensions. (education, health, nutrition, and housing). The checkmarks indicate the child is not deprived in that particular dimension, zero indicates deprivation.

In this chart, three out five children are poor (they suffer at least one deprivation). As mentioned in the previous paragraph, three fifths is neither the sum nor the average of the incidence of deprivation in each dimension. It is based on a holistic view of what happens to each child. Essentially the formulae that are used to estimate multidimensional poverty sum the presence of deprivations across the rows of the matrix and then the presence of poor children across the final column of the matrix.

As explained in the text, when economies and societies evolve, the thresholds in each of these dimensions should shift. Just as the calculation of the poverty line incorporates more goods and services when these are diffused into new consumption patterns, the levels below which children are considered deprived in each dimension change through time (and could be expected to be different from one society to another one). The following example shows, in a simple case of two dimensions, how this could be done.

Suppose we have three estimations several years apart. At each point in time there are ten children (obviously different children in each case).Footnote 35 There are only two dimensions in this case: education and health. It is assumed that the expansion of education is occurring faster than health. Thus, at the beginning, children are considered poor if they have not completed primary school (for the sake of argument this is set at 8 years of formal schooling). By the second period, this is raised to completion of secondary schooling (12 years). For health, the thresholds are as follows. Children are considered poor if they have not been immunized against any preventable disease at the time of the first measurement. By the second period, children are deprived of their right to health if they have received less than 3 vaccines. At least six vaccines are required not to be considered poor by the third period. The next three tables show a hypothetical example of the evolution of child poverty under these assumptions.

Four points can be made regarding this example. It can be observed that child poverty increases (from 50 to 70 %) and decreases (from 70 to 40 %) although deprivation increases in one dimension and decreases in the other one (deprivation in education first increases and then decreases while health shows the opposite pattern). This is the result of, as mentioned above, using an integrated view of the child as opposed to a sum or average of different dimensions. Also, the thresholds change but there are no additional dimensions, precluding the possibility of an ever increasing incidence of child poverty.

Thirdly, the threshold can change independently of each other. It depends upon the rate in which they are diffused and accepted by the population as the minimum standard for that particular dimension.Footnote 36 Finally the evolution of child poverty depends on the expansion and incorporation of higher standards to be considered deprived (similar to the notion of including additional goods and services in the minimum acceptable standard of living in the monetary poverty discussion) which is part of the Transformational Growth process.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Delamonica, E. Transformational Growth and Poverty: An Evolutionary Approach for Inter-Country and Inter-Temporal Comparisons of Poverty Incidence. Applied Research Quality Life 11, 387–411 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-014-9364-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-014-9364-9