Abstract

This study analyses changes in depressive symptomatology as a function of smoking status over time after a cognitive-behavioural intervention for smoking cessation among smokers with a history of depressive episode. The sample comprised 215 smokers with antecedents of depressive episode (Mage=45.03; 64.7% female). Depressive symptoms were assessed using BDI-II at baseline, end of intervention and at 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Depression was examined according to smoking status at 12-month follow-up: abstainers, relapsers and smokers. The linear mixed model showed a significant effect for time (F = 11.26, p < .001) and for the interaction between smoking status and time (F = 9.11, p < .001) in the variations in depression. Abstinent participants at 12 months experienced a reduction in depressive symptomatology. This change was significant when comparing abstainers to smokers and relapsers. The present study suggests an association between abstinence and reductions in depressive symptomatology for smokers with a history of depressive episode after an intervention for smoking cessation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Smoking is one of the leading modifiable causes of death and disability worldwide (US Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2020). Even though smoking prevalence has decreased over the past decades (World Health Organization [WHO], 2023), the prevalence of smokers with mental health disorders does not follow the same pattern. Weinberger et al. (2020) analysed the changes in smoking prevalence from 2005 to 2017, finding a significant decrease in smoking prevalence both among people with and without depression. However, these authors point out that the decrease in smoking prevalence was noticeably lower for smokers with depression.

The association between depression and smoking is well-established and has been extensively studied. People with depression are at higher risk of becoming smokers, and smoking seems to be associated with later depression (Fluharty et al., 2017; Sánchez-Villegas et al., 2021). Also, smokers with depression encounter more significant barriers to smoking cessation than those without depression (Ranjit et al., 2020) and show higher levels of nicotine dependence (Bainter et al., 2020), stronger urges to smoke when anticipating the relief from a negative mood state (Berlin & Singleton, 2008), higher relapse rates (Huffman et al., 2018; Zvolensky et al., 2015) and a more intense withdrawal syndrome when compared to smokers with lower levels of depressive symptomatology (Tucker et al., 2022).

Due to the difficulties that depressed smokers encounter in quitting and remaining abstinent, efforts are being made to improve smoking cessation interventions. For example, behavioural activation is a mood management component that has been gaining in popularity as an option to address this issue (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2023; Busch et al., 2017; Martínez-Vispo et al., 2019). Other efforts also include a combination of both behavioural activation and contingency management (Secades-Villa et al., 2019).

In contrast to all the factors that may hinder smoking cessation, smokers with mental health issues seem to be as motivated to quit as the general population (Siru et al., 2009). Some studies even suggest that higher levels of psychological distress are associated with higher motivation to quit smoking (Kastaun et al., 2022). The same is true for smokers with a past or current history of major depression; motivation to quit is high, and various attempts to quit are made among this population (Quinn et al., 2022). Considering that depressive disorders are classified as one of the leading causes of non-fatal health loss at a global level (WHO, 2017) and that tobacco smoking poses increased health risk, it is crucial to foster any strength among this population, such as high motivation, to promote and achieve successful smoking cessation. Therefore, continued research is warranted to improve smoking cessation interventions for smokers with depression.

Unfortunately, there is a common fear that smoking cessation among people with current or past major depression or other mental health disorders will worsen mental health conditions. This fear is reflected in the reluctance of mental health professionals to provide smoking cessation interventions (Lembke et al., 2007). Notwithstanding the reluctance, evidence suggests that smoking cessation improves depressive symptomatology among the general population (Hahad et al., 2022; Rodríguez-Cano et al., 2016), and other mental health variables such as depressive symptoms, anxiety and stress levels among clinical and general populations (Taylor et al., 2021). However, when studies target smokers with past or current depressive episode, results are mixed. For instance, a study conducted by Liu et al. (2021) concludes that abstinence does not result in lower depression in smokers with a history of major depressive disorder (MDD), but continued smoking does result in worse depressive symptomatology over time. Furthermore, Blalock et al. (2008) found that among a population of smokers with a history of major depression, 44% of abstainers reported a remission of their depressive disorder at the 3-month follow-up. On the other hand, other studies, like the one conducted by Glassman et al. (2001), conclude that smokers with a history of major depression who quit are at increased risk of depressive episode for at least the initial 6 months of abstinence. Therefore, further research is called for (Weinberger et al., 2013).

The present study aims to clarify further the relationship between smoking cessation and depression in people with a history of depressive episode. Changes in depressive symptomatology were examined based on smoking status over time after having received a cognitive-behavioural intervention to quit smoking. The analysis was conducted in a sample of smokers with antecedents of depressive episode.

Methods

Participants

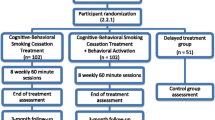

The initial sample was composed of 409 smokers who participated in a cognitive-behavioural intervention for smoking cessation in the Smoking Cessation and Addictive Disorders Unit at the University of Santiago de Compostela. The participants were recruited between 2015 and 2021.

To be included in the study, participants had to be 18 years old or older, willing to participate in the psychological intervention, smoke a minimum of six cigarettes per day and meet the criteria for past or current major depressive episode as assessed by the Major Depressive Episode Screener (MDE; Muñoz, 1998).

Exclusion criteria included the following: co-occurring substance use disorder (cocaine, cannabis, alcohol and/or opioids); diagnosis of a severe mental disorder (psychotic disorder and/or bipolar disorder); use of any tobacco products other than cigarettes; participation in the previous year in an effective psychological or pharmacological intervention for smoking cessation; and failing to attend the first intervention session.

After assessment and considering the criteria, a total of 194 participants were excluded for the following reasons: 1 smoker had co-occurring substance use disorder; 11 presented a diagnosis of a severe mental disorder; 8 had received an effective intervention for smoking cessation in the past year; 13 did not attend the first intervention session; and 161 participants did not meet criteria for a past or current depressive episode. The final sample on which the analysis was conducted comprised 215 smokers.

For this study, participants were grouped according to their smoking status at the 12-month follow-up: abstainers (n = 58), relapsers (n = 76) and smokers (n = 81). Abstinent participants were defined as those who self-reported not smoking during the 30 days before the follow-up conducted 12 months after the end of the intervention. Relapsers were defined as those who self-reported not smoking even one puff for the past 24 h at the last intervention session but reported smoking at any of the follow-ups conducted at 3, 6 or 12 months. Finally, the smoker category was defined as those participants who did not quit throughout the intervention sessions.

Abstinence was biochemically validated through measurements of carbon monoxide (CO) in exhaled breath using Bedfont’s Micro + Smokerlyzer (Bedfont Scientific Ltd., Maidstone, Kent, UK). The cut point for CO measurements was 5 particles per million (ppm) in exhaled breath (Benowitz et al., 2020). Any score over 5 ppm indicated that the participant was a smoker. Due to the situation generated by the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 (COVID-19) and the social distancing measures that were established, it was impossible to biochemically validate abstinence for 43.1% of our sample, leading to our having to rely exclusively on self-reported abstinence for this part of the sample.

Measures

In the context of this research, participants were assessed using a semi-structured interview and a set of questionnaires to collect socio-demographic variables and assess depression and smoking-related factors.

The following questionnaires were used for the pre-intervention assessment:

-

(1)

The Smoking Habit Questionnaire (SHQ; Becoña, 1994). The SHQ is a questionnaire used to gather general information on socio-demographic and smoking variables, such as age, sex, cigarettes per day (CPD) or educational level.

-

(2)

The Major Depressive Episode (MDE) Screener (Muñoz, 1998). The MDE Screener is a hetero-applied questionnaire that is used to identify past or current major depressive episodes.

-

(3)

The Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 2006). The BDI-II is a 21-item questionnaire that evaluates the presence and severity of depressive symptomatology. Participants completed this questionnaire at pre-intervention, post-intervention and at the 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-ups.

Procedure

A cognitive-behavioural smoking cessation intervention was applied in this study. The intervention was administered by counselling psychologists or clinical psychologists and was divided into eight weekly group sessions. Some of the components of this intervention were the following: self-report of daily cigarette use, graphic representation of daily consumption, psychoeducation about tobacco, strategies and activities for the avoidance and attenuation of withdrawal symptoms and craving, nicotine fading, stimulus control, behavioural activation and relapse prevention (Becoña, 2007; Martínez-Vispo et al., 2019).

The present study followed all ethical principles and was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Santiago de Compostela.

Analytical Strategy

Descriptive analyses based on smoking status at the 12-month follow-up (abstainers, smokers, and relapsers) were conducted for socio-demographic variables and pre-intervention depressive symptomatology and smoking-related factors. Additionally, differences in these data were examined using chi-square tests for qualitative variables, to which Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons were applied, and ANOVAs for continuous variables. Post hoc analyses were conducted to identify which groups differed from each other and in what direction.

In order to further assess the longitudinal changes in depressive symptomatology in the three groups, we applied a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with time (pre-intervention, post-intervention, 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-ups) as the within-subject factor and smoking status at the 12-month follow-up (abstainers, smokers and relapsers) as the between subject factor. Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used to correct for the non-sphericity of the data.

Linear mixed modelling (LMM) was conducted to compare the effect of smoking status at the 12-month follow-up (abstainers, smokers and relapsers) on depression measures over time with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation was used to account for missing data. Significant effects were followed up using pairwise comparisons.

All effects were reported with their corresponding confidence interval (CI), which was established at 95%. Any p-value lower than 0.05 was considered significant. All the analyses were conducted with SPSS version 28.

Results

Participant’s descriptive data based on smoking status at the 12-month follow-up is presented in Table 1. No significant differences were found as a function of smoking status at the 12-month follow-up for socio-demographic variables (sex, marital status, education level and employment) or for the pre-intervention BDI-II score. However, significant differences were found as a function of age and CPD.

Post hoc tests revealed that smokers at the 12-month follow-up were significantly older than relapsers (F2,212 = 3.91, SE = 1.73, p = .02) and that smokers consumed significantly more CPD at pre-intervention than abstainers (F2,212 = 4.34, SE = 1.43, p = .003) and relapsers (F2,212 = 3.13, SE = 1.33, p = .02).

After examining the differences in depressive symptomatology between abstainers, smokers and relapsers at each point in time through the ANOVA (see Table 2), no statistical differences were found at baseline or at the 3-month follow-up. Notwithstanding, the analysis showed statistical differences between groups at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. At the end of the intervention, smokers were significantly more depressed than abstainers and relapsers. At the 6- and 12-month follow-ups, relapsers’ depressive symptomatology seemed to return back to the levels displayed by smokers. Due to this tendency, at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups, both smokers and relapsers were significantly more depressed than abstainers. This tendency can be observed in Fig. 1.

The repeated measures analysis showed differences in depressive symptoms according to smoking status at 12-month follow-up (FGG (6.406, 186.341) = 2.636, p = .015, η2 = 0.059), adjusting for cigarettes per day at baseline (FGG, p > .05).

The mixed linear model showed a significant effect for time (F = 11.26, p < .001) and for the smoking status × time interaction (F = 9.11, p < 0001) in the change of the BDI-II scores. Concretely, abstinent participants experienced a significant reduction in depressive symptoms over time compared to relapsers and smokers (Table 3). After quitting smoking, participants who were abstinent at the 12-month follow-up had a mean reduction of 8.09 in their BDI-II scores from pre-intervention to the last follow-up, indicating an improvement of depressive symptomatology over time. BDI-II scores remained similar in the relapsed (from 13.55 at pre-intervention to 12.36 at the 12-month follow-up) and smoker group (from 14.11 to 14.28). The pairwise contrast revealed that mean change was statistically significant when comparing abstinent participants with smokers (mean difference − 5.22; SE = 1.37, p < .001, 95% CI [−7.82, −2.70]) and relapsed participants (mean difference − 3.20; SE = 1.3, p = .048, 95% CI [−6.39, −0.02]). No significant differences were found between smokers and relapsed participants (mean difference 2.02; SE = 1.30, p = .371, 95% CI [−1.13, 5.16]).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate changes in depressive symptomatology over time after a cognitive-behavioural intervention for smoking cessation, among smokers with a history of depressive episode. The results revealed that at the end of the intervention, participants with a history of depressive episode who were abstinent or who had relapsed at the 12-month follow-up were significantly less depressed than smokers. At the 6- and 12-month follow-ups, relapsers and smokers displayed more depressive symptomatology than those who remained abstinent at 12 months.

According to the literature, smokers with depressive symptoms or with a history of depression are more likely to relapse in the first month after smoking cessation (Cooper et al., 2016). Our data align with the literature, with relapses occurring mainly between the end of the intervention and the 3-month follow-up. As the relapse occurs and the smoking habit is reestablished, our results point toward a gradual increase in depressive symptomatology in the group of relapsers. At the 6- and 12-month follow-ups, there are no significant differences in depressive symptomatology between smokers and relapsers. Depressive symptoms return to levels similar to pre-intervention scores for the group of relapsers, whereas abstainers’ depression levels continue to decrease over time. This might explain the absence of significant differences in depression at the 3-month follow-up.

The mixed linear model that was performed showed a significant effect of being abstinent at the 12-month follow-up on depressive symptomatology reduction over time. Thus, smoking cessation is associated with an improvement of depressive symptomatology from pre-intervention to the 12-month follow-up among smokers with a history of depressive episode who manage to quit and maintain abstinence over time. These results are in line with those obtained for treatment-seeking smokers regardless of depression history. In studies like the one conducted by Rodríguez-Cano et al. (2016), abstainers and relapsers at the 12-month follow-up were significantly less depressed than smokers at the end of a cognitive-behavioural intervention for smoking cessation. Moreover, participants who managed to maintain abstinence at the 12-month follow-up continued to experience a decrease in depressive symptomatology in contrast with smokers and also with relapsers, whose symptoms started to increase as relapses took place. Similar results are also obtained for smokers with mental health issues (Taylor et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2023). In the systematic review conducted by Taylor et al., it is concluded that smoking cessation is associated with improvements in anxiety, depression and mixed depressed and anxious symptomatology when maintaining abstinence within a range of a few weeks to years, in comparison to continuing to smoke. Wu et al. also found that after a pharmacological intervention for smoking cessation, managing to maintain abstinence for at least 15 weeks and up to 24 weeks was associated with less anxiety and less depression in contrast with continuous smoking.

Conversely, other studies have not found decreases in depressive symptomatology after smoking cessation for smokers with a history of depressive episode. For instance, Liu et al. (2021) analysed depression severity over a 1-year follow-up period after a smoking cessation intervention among treatment-seeking smokers with past, current or no major depressive episode history. The authors found that continuous smoking seemed to be significantly associated with an increase in depressive symptomatology after a smoking cessation intervention, rather than abstinence being related to significant decreases in depressive symptoms. The high baseline depression scores among the participants in the study might explain this. Glassman et al. (2001) examined smokers with a past history of major depression, finding that at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups, abstainers were at a significantly higher risk of developing another episode of major depression than smokers. The results of this study do not refer to depression symptomatology severity. Also, a significant amount of data was missing at the follow-up among those who did not quit smoking after the intervention.

The results of the present study suggest that maintaining abstinence over time, especially in the long term, would reduce depressive symptomatology. Therefore, it is essential to promote smoking cessation among smokers in general and specifically among those with a history of depression to improve both physical and mental health.

This study contributes to the growing body of research that supports the fact that smoking cessation is associated with improvements in psychological variables, not only among treatment-seeking smokers in general but also among those with mental health issues. Dissipating the worry in patients that depression may get worse or more difficult to manage after smoking cessation is a critical practical implication of the present study. It is crucial to highlight studies like the one conducted by Prochaska et al. (2019), which concludes that exposing smokers with mental health issues to a smoking cessation ad campaign that features success stories of smokers with depression (i.e. achieving abstinence, improving mood) increases motivation to quit and quit attempts. Motivation to quit is a well-established key factor for attaining abstinence (Piñeiro et al., 2016). Therefore, it is vital to continue conducting studies in this line that strengthen the idea that smoking cessation is not only possible among people with mental health issues, but it is also beneficial due to improvements in both physical and mental health. Moreover, the results obtained not only have implications for smokers with a history of depressive episode but also for the health professionals who treat them. Mental health professionals perceive many obstacles to smoking cessation among people with mental health issues, hold negative attitudes towards quitting smoking and are more permissive when it comes to smoking (Sheals et al., 2016). They also ask less about smoking status, offer advice for smoking cessation less frequently and fear that smoking cessation will worsen symptoms (Cerci, 2023). Additionally, mental health professionals believe it should be the patients who demand help with smoking cessation (Zeeman et al., 2023). The results of the present study can be used as a motivation and a means for dissipating fears and deconstructing negative attitudes for healthcare professionals to offer and provide smoking cessation interventions to patients with mental health issues.

Among the limitations of this study, it is important to highlight the absence of biochemical validation for 43.1% of the sample. To analyse the possible impact this may have had on the data, we ran tests to compare abstinence rates between participants who had biochemical validation and those whose abstinence was self-reported. The analysis revealed no significant group differences (χ2 = 0.54, p = .461). Additionally, smoking cessation literature suggests that when in-person contact is not feasible, self-reported abstinence seems to be a reliable measure (Benowitz et al., 2020; West et al., 2005). Another limitation is that our results are not translatable to the general population of smokers or to smokers with a history of depressive episode who do not seek help to quit smoking. It is also relevant that the assessment questionnaires used for this study were self-reported, and such questionnaires can lead to a social desirability bias when reporting on depressive symptomatology.

The present study also has some strengths. Firstly, this study analyses the evolution of depressive symptoms after a smoking cessation intervention in a specific sample of smokers with a history of depressive episode, filling the gap in the literature that usually studies variations in psychological variables among non-specific populations (Taylor et al., 2021). Therefore, this study can be generalised to smokers who seek intervention for smoking cessation and who may be struggling to quit smoking due to psychological variables such as a history of depressive episode. Furthermore, the study offers an extensive time frame for follow-ups, allowing one to observe the variation of depressive symptomatology up to 1 year after the intervention, strengthening the conclusion that depression seems to decrease after smoking cessation. Finally, the present study includes an analysis of smokers, abstainers and relapsers in contrast with previous studies that generally analyse smokers versus abstainers (Wu et al., 2023).

Future research is warranted to analyse more specifically the changes that can be observed in depressive symptomatology for people with a history of depressive episode, and, consequently, to study in more detail its relationship with smoking relapse. Furthermore, due to the differences found in baseline smoking volume between abstainers, smokers and relapsers, it would be advisable for future studies to consider the impact of the number of cigarettes smoked per day on depressive symptoms and abstinence.

In conclusion, this study investigates the association between smoking cessation and depression among smokers with antecedents of depressive episode, confirming important reductions in depression for abstainers over time. The analysis presented can not only be used as support to encourage smokers with depression to achieve abstinence in smoking cessation interventions but also to encourage people struggling with depressive episodes to quit smoking as a means to improve mental health.

References

Audrain-McGovern, J., Wileyto, E. P., Ashare, R., Albelda, B., Manikandan, D., & Perkins, K. A. (2023). Behavioral activation for smoking cessation and the prevention of smoking cessation-related weight gain: A randomized trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2023.109792.

Bainter, T., Selya, A. S., & Oancea, S. C. (2020). A key indicator of nicotine dependence is associated with greater depression symptoms, after accounting for smoking behavior. PloS One, 15(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233656.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (2006). BDI-II. Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition. Manual. The Psychological Corporation.

Becoña, E. (1994). Evaluación de la conducta de fumar [Assessment of smoking behavior]. In J. L. Graña, (Ed.), Conductas adictivas: Teoría, evaluación y tratamiento [Addictive behaviors: Theory, assessment, and treatment] (pp. 403–454). Debate.

Becoña, E. (2007). Programa para dejar de fumar [Program to quit smoking]. Nova Galicia Edicións.

Benowitz, N. L., Bernert, J. T., Foulds, J., Hecht, S. S., Jacob, P., Jarvis, M. J., Joseph, A., Oncken, C., & Piper, M. E. (2020). Biochemical verification of tobacco use and abstinence: 2019 update. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 22(7), 1086–1097. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntz132.

Berlin, I., & Singleton, E. G. (2008). Nicotine dependence and urge to smoke predict negative health symptoms in smokers. Preventive Medicine, 47(4), 447–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.06.008.

Blalock, J. A., Robinson, J. D., Wetter, D. W., Schreindorfer, L. S., & Cinciripini, P. M. (2008). Nicotine withdrawal in smokers with current depressive disorders undergoing intensive smoking cessation treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22(1), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.122.

Busch, A. M., Tooley, E. M., Dunsiger, S., Chattillion, E. A., Srour, J. F., Pagoto, S. L., Kahler, C. W., & Borrelli, B. (2017). Behavioral activation for smoking cessation and mood management following a cardiac event: Results of a pilot randomised controlled trial. Bmc Public Health, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4250-7.

Cerci, D. (2023). Staff perspectives on smoking cessation treatment in German psychiatric hospitals. Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-022-01811-2.

Cooper, J., Borland, R., McKee, S. A., Yong, H. H., & Dugué, P. A. (2016). Depression motivates quit attempts but predicts relapse: Differential findings for gender from the International Tobacco Control Study. Addiction, 111(8), 1438–1447. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13290.

Fluharty, M., Taylor, A. E., Grabski, M., & Munafò, M. R. (2017). The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: A systematic review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw140.

Glassman, A. H., Covey, L. S., Stetner, F., & Rivelli, S. (2001). Smoking cessation and the course of major depression: A follow-up study. The Lancet, 357, 1929–1932. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05064-9.

Hahad, O., Beutel, M., Gilan, D. A., Michal, M., Schulz, A., Pfeiffer, N., König, J., Lackner, K., Wild, P., Daiber, A., & Münzel, T. (2022). The association of smoking and smoking cessation with prevalent and incident symptoms of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 313, 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.06.083.

Huffman, A. L., Bromberg, J. E., & Augustson, E. M. (2018). Lifetime depression, other mental illness, and smoking cessation. American Journal of Health Behavior, 42(4), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.42.4.9.

Kastaun, S., Brose, L. S., Scholz, E., Viechtbauer, W., & Kotz, D. (2022). Mental health symptoms and associations with tobacco smoking, dependence, motivation, and attempts to quit: Findings from a population survey in Germany (DEBRA Study). European Addiction Research, 28(4), 287–296. https://doi.org/10.1159/000523973.

Lembke, A., Johnson, K., & DeBattista, C. (2007). Depression and smoking cessation: Does the evidence support psychiatric practice? Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 3(4), 487–493.

Liu, N. H., Wu, C., Pérez-Stable, E. J., & Muñoz, R. F. (2021). Longitudinal association between smoking abstinence and depression severity in those with baseline current, past, and no history of major depressive episode in an international online tobacco cessation study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 23(2), 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntaa036.

Martínez-Vispo, C., Rodríguez-Cano, R., López-Durán, A., Senra, C., Fernández, D., Río, E., & Becoña, E. (2019). Cognitive-behavioral treatment with behavioral activation for smoking cessation: Randomized controlled trial. PloS One, 14(4). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214252.

Muñoz, R. (1998). Preventing major depression by promoting emotion regulation: A conceptual framework and some practical tools. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 1, 23–40.

Piñeiro, B., López-Durán, A., Río, D., Martínez, E. F., Brandon, Ú., T. H., & Becoña, E. (2016). Motivation to quit as a predictor of smoking cessation and abstinence maintenance among treated Spanish smokers. Addictive Behaviors, 53, 40–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.09.017.

Prochaska, J. J., Gates, E. F., Davis, K. C., Gutierrez, K., Prutzman, Y., & Rodes, R. (2019). The 2016 Tips from former Smokers® campaign: Associations with quit intentions and quit attempts among smokers with and without mental health conditions. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 21(5), 576–583. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nty241.

Quinn, M. H., Olonoff, M., Bauer, A. M., Fox, E., Jao, N., Lubitz, S. F., Leone, F., Gollan, J. K., Schnoll, R., & Hitsman, B. (2022). History and correlates of smoking cessation behaviors among individuals with current or past major depressive disorder enrolled in a smoking cessation trial. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 24(1), 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntab147.

Ranjit, A., Latvala, A., Kinnunen, T. H., Kaprio, J., & Korhonen, T. (2020). Depressive symptoms predict smoking cessation in a 20-year longitudinal study of adult twins. Addictive Behaviors, 108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106427.

Rodríguez-Cano, R., López-Durán, A., del Río, E. F., Martínez-Vispo, C., Martínez, Ú., & Becoña, E. (2016). Smoking cessation and depressive symptoms at 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-months follow-up. Journal of Affective Disorders, 191, 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.042.

Sánchez-Villegas, A., Gea, A., Lahortiga-Ramos, F., Martínez-González, J., Molero, P., & Martínez-González, M. (2021). Á. Bidirectional association between tobacco use and depression risk in the SUN cohort study. Adicciones. https://doi.org/10.20882/adicciones.1725.

Secades-Villa, R., González-Roz, A., Vallejo-Seco, G., Weidberg, S., García-Pérez, Á., & Alonso-Pérez, F. (2019). Additive effectiveness of contingency management on cognitive behavioural treatment for smokers with depression: Six-month abstinence and depression outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.06.003.

Sheals, K., Tombor, I., McNeill, A., & Shahab, L. (2016). A mixed-method systematic review and meta-analysis of mental health professionals’ attitudes toward smoking and smoking cessation among people with mental illnesses. Addiction, 111(9), 1536–1553. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13387.

Siru, R., Hulse, G. K., & Tait, R. J. (2009). Assessing motivation to quit smoking in people with mental illness: A review. Addiction, 104(5), 719–733. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02545.x.

Taylor, G. M., Lindson, N., Farley, A., Leinberger-Jabari, A., Sawyer, K., Naudé, T. W., Theodoulou, R., King, A., Burke, N., C., & Aveyard, P. (2021). Smoking cessation for improving mental health. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3(3). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013522.pub2.

Tucker, C. J., Bello, M. S., Weinberger, A. H., D’Orazio, L. M., Kirkpatrick, M. G., & Pang, R. D. (2022). Association of depression symptom level with smoking urges, cigarette withdrawal, and smoking reinstatement: A preliminary laboratory study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109267.

U. S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS). (2020). Smoking cessation: A report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Services, Office of the Surgeon General.

Weinberger, A. H., Mazure, C. M., Morlett, A., & McKee, S. A. (2013). Two decades of smoking cessation treatment research on smokers with depression: 1990–2010. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 15(6), 1014–1031. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nts213.

Weinberger, A. H., Chaiton, M. O., Zhu, J., Wall, M. M., Hasin, D. S., & Goodwin, R. D. (2020). Trends in the prevalence of current, daily, and nondaily cigarette smoking and quit ratios by depression status in the US: 2005–2017. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 58(5), 691–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.12.023.

West, R., Hajek, P., Stead, L., & Stapleton, J. (2005). Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: Proposal for a common standard. Addiction, 100(3), 299–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00995.x.

World Health Organization (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders. Global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/depression-global-health-estimates.

World Health Organization (2023). WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2023: Protect people from tobacco smoke. Geneva: World Health Organization.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240077164.

Wu, A. D., Gao, M., Aveyard, P., & Taylor, G. (2023). Smoking cessation and changes in anxiety and depression in adults with and without psychiatric disorders. Journal of the American Medical Association, 6(5). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.16111.

Zeeman, A. D., Jonker, J., Groeneveld, L., de Krijger, E. M., & Meijer, E. (2023). Clients are the problem owners’: A qualitative study into professionals’ and clients’ perceptions of smoking cessation care for smokers with mental illness. Advances in Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/18387357.2023.2262627.

Zvolensky, M. J., Bakhshaie, J., Sheffer, C., Perez, A., & Goodwin, R. D. (2015). Major depressive disorder and smoking relapse among adults in the United States: A 10-year, prospective investigation. Psychiatry Research, 226(1), 73–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.064.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants in this study, and María Ramos-Carro for all the support during the elaboration of this research paper.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This research was supported by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (Project PSI2015-66755-R), and Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (Project PID2019-109400RB-100) of Spain and co-financed by FEDER (European Regional Development Fund).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation, E.M.A., C.M.V., A.L. and E.B.; methodology, E.M.A., C.M.V., A.L. and E.B.; validation, C.M.V., A.L. and E.B.; formal analysis, C.M.V. and E.M.A.; investigation, E.M.A., C.M.V., A.L. and E.B.; resources, E.B.; data curation, E.M.A., C.M.V. and A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M.A.; writing—review and editing, C.M.V., A.L. and E.B; visualisation, E.M.A., C.M.V., A.L. and E.B.; supervision, A.L. and E.B; project administration, E.B. and A.L.; funding acquisition, E.B. and A.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moss-Alonso, E., Martínez-Vispo, C., López-Durán, A. et al. Does Quitting Smoking Affect Depressive Symptoms? A Longitudinal Study Based on Treatment-Seeking Smokers with a History of Depressive Episode. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01317-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01317-w