Abstract

Recent research has focused on investigating the impact of sports betting inducements on individuals' gambling behaviour. Younger people are an important demographic, as they exhibit higher rates of sports betting engagement and are at a formative stage of life where they may be more vulnerable to potential harm. This study investigates how young people perceive the impact of four different types of betting inducements on betting behaviour. These inducements included sign-up, bonus bets, increased odds and stake-back offers. We recruited 130 participants (71.5% male) aged between 18 and 24 to complete an online survey. Participants were presented with four betting inducements that resembled social media betting advertisements. Participants were subsequently asked about how likely they were to place a bet and if they would be more likely to engage in higher-risk betting had they received each inducement. They also reported their perceived value of each inducement. The findings indicate that sign-up and bonus bet inducements were perceived to have a stronger influence on increasing betting behaviour and engaging in higher-risk gambling compared to stake-back and increased odds inducements. These inducements were also seen as having greater promotional value. Those who experience gambling problems were found to be more inclined to believe that incentives could motivate them to engage in riskier gambling behaviours. The study provides needed data on the effects of exposing participants to purposely designed promotions for betting inducements. The findings suggest that implementing policies to restrict inducements for sports betting could help mitigate gambling-related harm among young people. This appears especially true for incentives that lower the cost of betting or offer free bets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Sports fans are frequently inundated with advertising for sports betting. This advertising has been observed to primarily promote more complex betting types such as in-play betting and betting offers such as enhanced odds and sign-up bonuses (Killick & Griffiths, 2020; Newall et al., 2022). For example, a UK study found that viewers of the 2018 FIFA World Cup saw an average of 2.16 advertisements for live sports betting per broadcast (Newall et al., 2019). Young people's exposure to sports betting advertising is of particular concern for several reasons. Sports betting is a prevalent activity among young individuals, with males being the demographic group that is most likely to participate in this form of gambling (Rockloff et al., 2020). In addition, young people are prone to participating in risky behaviours, notably in the recreational and financial contexts that pertain to gambling (Rolison et al., 2014; Stenstrom et al., 2011). This risk-taking propensity is notably more pronounced in males (Byrnes et al., 1999; Frey et al., 2021) and is exacerbated in the presence of other males (Fischer & Hills, 2012), a phenomenon known as the "young male syndrome” (Wilson & Daly, 1985). Due to their propensity for sports betting, it is important to investigate any environmental factors that might influence young people's gambling behaviour.

The Current State of Sports Betting Marketing

Young people, those between the ages of 18 and 24, represent a generation that has grown up during the era of the internet and social media. They are highly engaged with digital technology and spend more time on the internet and on social media than other generations (Australian Communications & Media Authority, 2021a; Auxier & Anderson, 2021; Twenge et al., 2019). Due to its highly personalised nature, internet advertising is considerably more advanced than traditional forms of advertising. The modern practise of tailoring advertisements based on an individual's previous online behaviour is known as online behavioural advertising (Smit et al., 2014). This is achieved through specialised advertising technology companies, also known as “ad-tech” businesses (Boyland et al., 2020), which collect data on a person’s online activities through tracking cookies (Smit et al., 2014). Advertisements are then targeted at individuals based on this data (Pascucci et al., 2023). The adoption of this data-driven marketing approach has resulted in the dissemination of highly personalised and relevant promotional content to consumers, which has been demonstrated to possess a greater capacity for capturing consumers’ attention relative to non-personalised promotional content (Bang & Wojdynski, 2016; Kaspar et al., 2019). In the context of sports betting, bookmakers may use “big data” to target advertisements to specific demographics, such as young males who exhibit a propensity to bet on sports. Existing sports bettors are likely to receive targeted advertising from platforms to which they have accounts that reflects their particular betting preferences based on their betting history, such as the specific sports or teams on which they are likely to place bets.

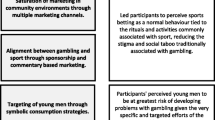

There are numerous advertising strategies that marketers can use to promote sports betting, ranging from overt to subtle, all of which can be effectively leveraged through digital media. Sponsored advertising is a more conventional type of advertising in which a company pays to have its logo aligned with a particular brand, usually a sport, with the purposes of increasing brand awareness and enhancing its image (Hsiao et al., 2021). This marketing strategy has been extensively researched in the sports betting advertising literature (e.g., Bunn et al., 2018; Deans et al., 2017; Djohari et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2016) and is frequently demonstrated by the placement of sponsors’ logos on jerseys or billboards around stadiums. The emergence of digital marketing has resulted in an evolution in advertising strategies that may be better able to connect with younger demographics compared to traditional advertising approaches. One such example is influencer marketing, which involves companies leveraging social media influencers as sponsored endorsers or affiliates to promote their products (Ki et al., 2020; Martínez-López et al., 2020). The effectiveness of this approach is explained by the human brand theory (Kim & Kim, 2022; Thomson, 2006), which posits that the emotional attachments that individuals form with influencers can be leveraged to enhance the effectiveness of product marketing through brand loyalty and commitment. Affiliate marketing may be the most prominent example of this advertising technique, whereby affiliate influencers endorse promotion codes or direct hyperlinks, through which they earn a commission based on the referrals they generate (Dajah, 2020). Influencer marketing is commonly encountered on social media platforms and constitutes a marketing strategy that has yet to be thoroughly researched in the context of sports betting.

Advertising on social media and news feeds has facilitated an advertising technique known as native advertising. The purpose of this technique is to seamlessly integrate display advertising within a media feed's normal content (Aribarg & Schwartz, 2019). For example, this could be an advertisement positioned within the featured articles section of an online news platform, designed to resemble a regular article. It has been found that this marketing strategy is less noticeable to users during their media browsing (Wojdynski, 2016) and results in more engagement with advertising, as evidenced by increased click-through rates (Aribarg & Schwartz, 2019). In the context of sports betting, native advertising can manifest itself in people’s social media feeds, disguising itself as just another social media post. The inconspicuous nature of native advertising, coupled with its propensity to attract greater click-through rates (Aribarg & Schwartz, 2019), raises concerns in regards to its influence on younger people, who are highly engaged with social media.

The marketing strategies described represent modern marketing strategies through which young people may be exposed to sports betting advertising or may develop an awareness of betting brands. Despite being less obvious than traditional advertising methods, these strategies may possess the capacity to influence the betting behaviours and intentions of young people. In Australia, the current regulations set out by the Australian Communications and Media Authority (2021b) mainly focus on restricting sports betting advertising on broadcast television but largely neglect advertising on modern media sources. Therefore, additional research is necessary to determine whether these modern advertising strategies have a detrimental effect on young individuals, which may provide insights that can guide future advertising policies.

Betting Inducement Advertising

Several studies have examined the impact of sports betting inducements on individuals’ gambling behaviour, although they have not specifically focused on young people. Russell et al., (2018a, b) conducted a study that observed a relationship between receiving text message advertisements and the frequency and monetary value of betting behaviour. Bonus bet inducements were found to have the strongest influence on individuals' decisions to place a wager. Notably, direct messages without incentives were found to be just as effective in prompting people to bet as messages with incentives. In another study, Browne et al. (2019) reported that betting marketing increased both the likelihood of placing bets and the amount of money wagered. The inducement type with the greatest impact on betting expenditure was the reduced risk promotion, which reduces the risk of a bet by providing a portion of the lost stake back in the form of bet credits, cash, or bonus bets. However, similar to Russell et al. and’s (2018a, b) findings, exposure to general betting advertisements had a stronger association with the likelihood of engaging in betting behaviour compared to inducement advertisements. The study also revealed that betting advertising had an impact on indicators of gambling-related harm. Specifically, exposure to betting advertising was linked to betting without prior intention and exceeding intended spending among race bettors, but not sports bettors. Both studies did not find any differences between problem gambling categories, suggesting that individuals with gambling problems were not more susceptible to the influence of betting advertising compared to non-problem gamblers. Overall, these studies suggest that betting inducements can be influential, and betting advertising may serve as a cue to prompt individuals to gamble.

Overall, the existing evidence demonstrates that advertising for sports betting promotions and betting advertising in general is associated with increased frequency of betting and greater money spent gambling. However, the available evidence does not appear to support the notion that promotions have a greater impact on problem gamblers. One study, however, found a relationship between participants’ use of betting inducements and their tendency towards impulse betting (Hing et al., 2018), which is a characteristic associated with problem gambling (Hing et al., 2017a, b). The study also revealed that being young and male was a significant predictor of using betting inducements (Hing et al., 2018). Young people are of particular concern due to their increased tendency towards participating in sports betting (Rockloff et al., 2020), their increased disposition towards engaging in risky behaviours (Rolison et al., 2014; Stenstrom et al., 2011), and the general instability that characterises this period of development (Arnett, 2000, 2014). These factors, in conjunction with the pervasiveness of sports betting advertisements to which they are likely to be exposed, suggest that it would be beneficial to carry out research on the impact of these promotions specifically on young people.

The Present Study

The aim of the present study was to evaluate young people’s perceptions of sports betting advertising for betting inducements (18–24 years old). Specifically, the research explored the gap in the literature regarding which betting inducements are perceived to be most influential to young people. The current investigation employed purposefully designed sports betting promotions that resemble social media banner advertisements. This is due to the fact that young individuals are highly active on social media, and there are limited studies in the extant literature that specifically examine the advertising of sports betting on social media. The types of sports betting inducements that were used include bonus bets, sign-up offers, increased odds, and stake backs. These were selected based on the findings from Browne et al. (2019) and Russell et al., (2018a, b), as well as by what young people in a previous study (Di Censo et al., 2023a) reported they encountered most often and found most appealing during the 2022 FIFA World Cup.

The first objective of this study was to identify the sports betting inducements that young people perceive as most likely to lead them to engage in betting. The second objective was to determine the inducements that young people consider to be the most advantageous or “good deals” from a consumer’s perspective. The third objective was to determine the inducements that young people believe would result in increased engagement in high-risk gambling activities, such as exceeding their intended gambling budget or being enticed into gambling when not initially intending to do so. Due to the ongoing development of the literature, it is challenging to anticipate which inducements will be perceived as the most influential. The existing body of literature provides support for at least three of the incentives. Therefore, we abstain from making any predictions regarding which inducement will be perceived as the most influential. A fourth objective of the study was to determine whether gambling inducements were perceived to exacerbate gambling problems among higher-risk gamblers. The final objective was to determine the function that young people perceived each inducement to serve.

Method

Participants

To be eligible for this study, participants were required to be between the ages of 18 and 24 and reside in either the UK, Australia, or New Zealand. People from these nations were selected to participate because their regulations on sports betting and its advertising are similar. Participants were required to have prior experience with sports betting, which demonstrates that they are familiar with how betting promotions work. We conducted a power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) software to ascertain the necessary sample size. The sample size required for a factorial ANOVA with two between-subject levels (PGSI) and four within-subject levels (inducements), a significance level of p = 0.001, a medium effect size (ηp2 = 0.06), and a power of 0.95 was calculated to be N = 62.

Materials

Demographic Questions

General questions about participants’ age, gender, and level of education were asked as part of the study. In addition, participants were asked to indicate their frequency of sports betting on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from never to daily and more frequently.

Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI)

The PGSI was used to determine participants' problem gambling scores (Ferris & Wynne, 2001). This nine-item scale has four possible responses, ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (almost always). The PGSI has a score range of 0 to 27. The scores are usually interpreted into four categories: non-problem (0), low risk (1–2), moderate risk (3–7), and problem gambler (8 +). A median split (i.e., scores of 2) was used to divide participants into two groups: lower-risk gamblers (non-problem to lower-risk gamblers) and higher-risk gamblers (moderate-risk to problem gamblers). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88, which suggests a high level of internal consistency.

Impulsivity

Impulsivity was assessed using the Short UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale (SUPPS-P) (Cyders et al., 2014). Participants indicated their agreement with 20 statements using a four-point scale ranging from strongly agree (0) to strongly disagree (3). Scores on the scale can range from 0 to 60. The SUPPS-P contains five sub-scales: positive urgency, negative urgency, lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance, and sensation seeking. However, we used the entire scale as a general measure of impulsivity. The Cronbach's alpha for the scale was 0.75, which indicated acceptable internal reliability.

Advertising for Inducements

We used professionally designed social media advertising banners for the fictional betting company Bet433 to promote several sports betting offers. These included offers for stake back, sign-up bonuses, increased odds, and bonus bets. We had the advertising banners professionally designed as recommended by Geuens and De Pelsmacker (2017) to increase the external validity of our findings. The content of the advertisements was adapted from various real sports betting advertisements.

Perceptions of Sports Betting Promotions Scale (PSBP Scale)

A 23-item scale was developed to capture three aspects of young people’s beliefs about the advertising for sports betting inducements. These include bet placement, inducement value, and high-risk gambling. On a seven-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree, participants indicated how much they agreed with each statement. Described below are the three subscales of the PSBP scale:

Bet Placement

This is a four-item subscale that assesses how much young people believe that the inducement advertising would influence them to place a bet. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.90 for the stake-back promotion, 0.92 for the sign-up promotion, 0.84 for the increased odds promotion, and 0.89 for the bonus bet promotion. An example of a scale item is: “If I received this inducement, I would place a bet.”

Inducement Value

This is a six-item subscale that assesses the perceived utility of gambling inducements. Each of the following criteria was represented: it reduces cost, increases benefit, is fair, fits with bettors' habits, upholds bettors' loyalty, and increases the likelihood that they will tell others. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.91 for the stake-back promotion, 0.90 for the sign-up promotion, 0.89 for the increased odds promotion, and 0.91 for the bonus bet promotion. An example of a scale item is: “Betting is more affordable thanks to this inducement.”

High-Risk Gambling

This is a 10-item scale that measures the extent to which participants believe an inducement would influence them to engage in high-risk gambling behaviours. Item development was informed by the diagnostic criteria for gambling disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; World Health Organization, 2019) and symptoms of problem gambling (Ferris & Wynne, 2001). The domain that each item represents is noted below in parenthesis. Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.93 for the stake-back promotion, 0.90 for the sign-up promotion, 0.93 for the increased odds promotion, and 0.90 for the bonus bet promotion. An example of a scale item is: “I could use this inducement to recoup my losses.”

Functions of Inducements Measure

Using a single-item measure, we asked participants what purpose they thought each inducement served. The response options included statements related to risk reduction, increased probability of winning, increased earnings, and decreased cost of betting.

Procedure

We used the online research panel Prolific to recruit people to take part in the survey, and Qualtrics was used to run the survey. Out of the 2,247 individuals who met the criteria for participation on the panel, a total of 179 individuals completed the survey. Participants first answered the demographic questions, a question about their regular gambling participation, and the PGSI. Participants were then shown each inducement one at a time and asked to complete the PSBP Scale and the Functions of Inducements Measure for each inducement. To minimise order effects, participants were randomly exposed to the advertisements for the inducements. Participants were then asked if they had read the terms and conditions for the inducements. They were then debriefed and redirected to Prolific.

On average, it took participants 10 min and 18 s to complete the survey, and they were paid $3.93 AUD for their time. The data were quality checked to eliminate any patterned responses, logically inconsistent responses, or very short survey completions (i.e., under 7 min and 30 s). Forty-nine participants were excluded from the analysis due to these reasons. The current study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Subcommittee of the University of Adelaide's School of Psychology; project number: H-2023/15.

Analytic Strategy

The analyses were conducted using SPSS v.28 (IBM Corp., 2021). We conducted three 2 × 4 mixed ANOVAs to examine which promotion had the greatest effect on the participants' ratings for bet placement, inducement value, and high-risk gambling. The PGSI was the between-groups factor with two levels: lower-risk and higher-risk. Inducement type was the within-subjects factor, with four levels (i.e., stake-back, sign-up, increased odds, and bonus bet). The interaction effect between inducement type and PGSI allowed us to determine whether higher-risk gamblers were more likely than lower-risk gamblers to believe that a particular inducement was more likely to influence them. To examine group differences, pairwise comparisons were carried out using Bonferroni corrections.

We performed hierarchical regression analyses to determine if individuals at a higher risk of gambling problems were more likely to perceive promotions as influencing their engagement in high-risk gambling behaviours. Our analysis involved four separate hierarchical regressions. The outcome variable was the PGSI, and the predictors were participant scores on the high-risk gambling subscale of the PSBP. The regression model was constructed in a stepwise manner to determine if each inducement’s score could predict PGSI scores beyond other established predictors. In the first step, we included gender (being male) (Hing et al., 2017a, b; Hing et al., 2016; Russell et al., 2018a, 2018b) and regular gambling participation (Hing et al., 2017a, b; Hing et al., 2016) as predictors, based on prior research that has established their ability to predict PGSI. Impulsivity was introduced as a predictor in the second step, building on previous findings that highlight its association with the PGSI (e.g., Blain et al., 2015; Haw, 2015; Howe et al., 2019; Russell et al., 2018a, b). The high-risk gambling subscale scores for each inducement were included as predictors in the final step of each regression.

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 130 participants were recruited for this study. As indicated in Table 1, the majority of participants were from the United Kingdom. All participants were between the ages of 18 and 24, with a mean age of 22. Most participants were male (71.5%). On average, participants gambled once a month. 22 participants (16.9%) reported they had not bet on a sporting event in the past month, whereas 24 people (18.5%) reported they bet on sports at least once a week. Participants scored an average of 3.7 (Mdn = 2) on the PGSI.

Statistical Analysis

The Perceived Influence of Inducements

We performed three separate analyses to examine how much young people believed that each betting inducement could affect their likelihood of placing a bet, how valuable they perceived each inducement to be, and their potential impact on high-risk gambling behaviours. Refer to Table 2 for a summary of descriptive statistics and Fig. 1 for a graphical representation of the data in each analysis. The results of the inferential tests are summarised below:

Likelihood of Placing a Bet

We conducted a 2 × 4 mixed ANOVA, where we looked at the impact of PGSI risk level (lower-risk and higher-risk) as the between-groups factor and inducement type (sign-up, increased odds, stake-back, and bonus bet) as the within-subjects factor on perceived likelihood of placing a bet. The assumption of sphericity was violated (ε = 0.76), so the Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used. We found a significant main effect of inducement type, F(2.27, 290.33) = 80.98, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.39. Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction (adjusted α = 0.0083) revealed that participants believed the sign-up inducement was more likely to lead to bet placement than the increased odds (t(129) = 11.70, p < 0.001, d = 1.03) and stake-back (t(129) = 9.01, p < 0.001, d = 0.79) inducements. The bonus bet inducement was also perceived as significantly more likely to lead to bet placement than the increased odds (t(129) = 11.08, p < 0.001 d = 0.97) and stake-back (t(129) = 7.56, p < 0.001, d = 0.66) inducements. Participants believed that the stake-back inducement was more influential compared to the increased odds inducement (t(129) = 3.72, p < 0.001, d = 0.33). However, there was no significant difference between scores for the sign-up and bonus bet inducements (t(129) = 1.76, p = 0.080, d = 0.16). Additionally, there was a main effect for the PGSI split (F(1, 128) = 27.69, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.18), indicating that higher-risk gamblers were more likely to be influenced by the inducements than lower-risk gamblers. However, there was no significant interaction effect between inducement type and PGSI category, F(2.27, 290.33) = 0.836, p = 0.45, ηp2 = 0.01.

Perceived Inducement Value

We conducted a similar 2 × 4 mixed ANOVA to examine the effects of PGSI and inducement type on perceived inducement value. The Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used due to the violation of sphericity (ε = 0.73). The main effect of inducement type was significant, F(2.20, 281.98) = 79.41, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.38. Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction (adjusted α = 0.0083) revealed that participants believed the sign-up inducement was significantly more valuable than the stake-back (t(129) = 8.61, p < 0.001, d = 0.76) and increased odds (t(129) = 11.57, p < 0.001, d = 1.02) inducements. The bonus bet inducement was also perceived as significantly more valuable than the stake-back (t(129) = 7.54, p < 0.001, d = 0.66) and increased odds (t(129) = 10.92, p < 0.001, d = 0.96) inducements. Participants perceived the stake-back inducement to be more valuable than the increased odds inducement (t(129) = 3.79, p < 0.001, d = 0.33). However, there was no significant difference between the scores for the sign-up and bonus bet inducements (t(129) = 1.64, p = 0.104, d = 0.14). There was also a main effect for the PGSI split (F(1, 128) = 27.69, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.16), indicating that higher-risk gamblers valued the inducements more than lower-risk gamblers. No significant interaction effect between inducement type and PGSI category was found, F(2.27, 290.33) = 0.84, p = 0.45, ηp2 = 0.01.

Influence on Higher-Risk Gambling

In the final analysis, another 2 × 4 mixed ANOVA examined the effects of PGSI and inducement type on the perceived likelihood of engaging in higher-risk gambling behaviours. The Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used due to the violation of sphericity (ε = 0.80). The main effect of inducement type was significant, F(2.41, 308.30) = 65.30, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.34. Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction (adjusted α = 0.0083) revealed that participants believed that the sign-up inducement could have a greater impact on their engagement in higher-risk gambling behaviours compared to the stake-back (t(129) = 7.26, p < 0.001, d = 0.64) and increased odds (t(129) = 11.12, p < 0.001, d = 0.98) inducements. The bonus bet inducement was also perceived as significantly more likely to lead to higher-risk gambling than the stake-back (t(129) = 5.78, p < 0.001, d = 0.51) and increased odds (t(129) = 10.30, p < 0.001, d = 0.90) inducements. Participants believed that the stake-back inducement could have a greater impact than the increased odds inducement (t(129) = 4.54, p < 0.001, d = 0.40). However, after applying the Bonferroni correction, there was no significant difference between the scores for the sign-up and bonus bet inducements (t(129) = 2.04, p = 0.43, d = 0.18). There was a main effect for the PGSI split (F(1, 128) = 31.50, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 20), indicating that higher-risk gamblers were more likely to believe the inducements could influence them to engage in higher-risk gambling. No significant interaction effect between inducement type and PGSI group was found, F(2.41, 308.30) = 1.83, p = 0.15, ηp2 = 0.01.

Are Gambling Inducements Perceived to Exacerbate Gambling Problems Among Young Higher-Risk Gamblers?

Bivariate correlations (Table 3) showed that scores on the high-risk gambling subscale for each of the four promotions had a significant and positive correlation with the PGSI. Furthermore, the PGSI was positively correlated with both regular gambling engagement and impulsivity. The PGSI was not correlated with being male.

We conducted four hierarchical regression models to determine whether the promotions were perceived to be more likely to exacerbate gambling problems among higher-risk gamblers. Regular gambling behaviour and gender were entered as predictors in the first step, followed by impulsivity in the second step and the high-risk gambling subscale scores in the third step. The findings of the regressions are summarised in the note sections of Tables 4, 5, 6, and 7. Regular gambling behavior, but not gender, emerged as a significant predictor of PGSI. The inclusion of impulsivity in the second step of the regression improved model fit. Lastly, in the third step of their respective regression models, high-risk gambling scores for each inducement were found to be statistically significant predictors of PGSI scores. The model that included subscale scores for the sign-up inducement explained the greatest variance in PGSI scores (R2 = 0.32). The findings suggest that those who are at a higher risk of experiencing gambling problems are more likely to believe that betting inducements exacerbate their gambling problems.

For Step 1, R2 = 0.147, Adjusted R2 = 0.133, F(2,126) = 10.826, p < 0.001. For Step 2, R2 = 0.237, Adjusted R2 = 0.218, ΔR2 = 0.090, Fchange(1, 125) = 14.712, p < 0.001. For Step 3, R2 = 0.318, Adjusted R2 = 0.296, ΔR2 = 0.081, Fchange(1, 124) = 14.808, p < 0.001. B = unstandardised regression coefficient, SE = standard error, β = standardised regression coefficient, t = t value, p = p value, CI = Confidence Interval.

What Purpose Do Young People Believe Each Inducement Served?

Table 8 displays what the participants believed were the purposes that each inducement served. The majority of respondents (77.7%) believed that if they lost a wager, they would lose less with the stake-back offer. Just over half of respondents (51.5%) believed that the sign-up inducement would enable them to gamble with less money, whereas a noteworthy minority (26.9%) believed that the promotion would result in them earning more money when betting. Half of respondents (50.8%) believe that the increased odds promotion would result in higher bet wins, whereas 37.7% of respondents indicated that this promotion increased their chances of winning a wager. Lastly, although over two-fifths of participants (43.1%) believed the bonus bet promotion would reduce the cost of wagering, nearly one-third of respondents (32.3%) believed the inducement would help them earn more money when betting.

How Many People Read the Terms and Conditions?

A total of 46.2% of respondents reported that they had read the terms and conditions for each of the promotions; 30.8% reported reading the terms and conditions for some of the promotions, and 23.1% did not read the terms and conditions for any of the promotions. Since participants were specifically instructed to read the terms and conditions of the inducements, these results should be interpreted with caution.

Discussion

The current study investigated how young people perceived the influence of four types of betting inducements presented in the form of internet advertising banners. The first and third objectives pertained to determining what inducements young people thought would make them more likely to gamble and engage in high-risk gambling behaviours. It was found that sign-up and bonus bet offers had a greater impact compared to stake-back and increased odds offers. The second objective was to examine the perceived value of the different inducements. It was discovered that sign-up and bonus bet inducements were also considered to have the highest promotional value, which suggests that the perceived impact of a betting inducement is connected to its value. The fourth objective of the study was to examine whether young people with higher problem gambling scores perceived that the inducements could influence them to engage in high-risk gambling. The analysis revealed that this was the case, with the sign-up inducement having the greatest impact. This suggests that inducements, and particularly sign-up offers, may possess the potential to influence an increase in gambling harm among young people with existing gambling problems. The study's fifth objective explored the purpose participants believed each inducement served. The stake-back inducement was perceived as a means to minimise losses, the sign-up inducement as a method to facilitate gambling with less money, the increased odds inducement as a strategy to increase the amount of money one can win, and the bonus bet inducement as a way to both reduce betting costs and increase winnings.

Young people perceived sign-up and bonus bet inducements as the most influential betting promotions, both in terms of likelihood to lead to betting and likelihood to engage in higher-risk betting, as well as being perceived as having the most promotional value. These findings can be explained by the zero-price effect, which refers to the phenomenon where people exhibit a preference for goods that are offered for free compared to when they are offered at a low price (Chandran & Morwitz, 2006; Shampanier et al., 2007). This preference shift is non-linear, meaning that the increase in preference is not proportional to the decrease in price. Notably, the zero-price effect can cause people to switch their preferences from high-value to low-value options only when the low-value option is offered for free (Shampanier et al., 2007). One explanation for the zero-price effect is that because there are no costs involved in accepting a free offer, individuals do not need to weigh the benefits against the costs. Another explanation for the zero-price effect is that people may anticipate the regret they might feel had they passed up a free good (i.e., FoMO). In the current study, there was a key difference between the bonus bet and sign-up offers regarding their cost. The bonus bet promotion required that the bettor place a bet to obtain the bonus bet, incurring some expense, while the sign-up offer did not entail any financial risk for the bettor to obtain the incentive. This may explain why the sign-up offer was more likely to be perceived as influencing higher-risk gambling among those with higher problem gambling scores. The findings of the current study suggest that betting promotions that have no cost have the greatest impact on young people, which gives evidence in support of the prohibition of such promotions in Australia (National consumer protection framework for online wagering in Australia, 2022).

The current study identified reduced risk promotion as the third most influential betting promotion, which could be best described by the risk homeostasis theory, also referred to as risk compensation (Wilde, 1982). Risk compensation refers to individuals’ tendency to adjust their behaviour based on their risk tolerance (Trimpop, 1994). If there is a safety mechanism in place that reduces risk, a person may be inclined to take on more risk to achieve risk homeostasis. In the context of multi-bets, which involve multiple wager selections aiming to maximise potential winnings, there is an inherent higher level of risk compared to conventional betting types. To mitigate this risk and promote multi-bet participation, the stake-back promotion employs a risk reduction strategy. It offers bettors a refund of their stake if a certain number of selections fail to win. Consequently, the stake-back promotion acts as a risk compensation measure, reducing the perceived risk associated with this already risky wager and encouraging multi-bet wagering. Although the present study found that the stake-back promotion was less influential than the sign-up and bonus bet promotions, the lack of a control group precluded us from evaluating the effectiveness of the stake-back offer compared to no promotional incentive (i.e., a multi-bet without the stake-back offer). However, Browne et al. (2019) found that stake-back offers are highly effective in increasing betting expenditure, which supports the notion that risk-reducing promotions can be an effective incentive for betting.

In the current study, participants rated the increased odds promotion as the least influential inducement. We were also unable to find that problem gamblers were more receptive to the increased odds inducement, which differs from the findings of previous research (Killick & Griffiths, 2020). However, as noted earlier, the present investigation did not include a control group for comparative purposes, as we exclusively compared various inducements among themselves. As a result, it is plausible that the increased odds promotion may have more influence than the absence of any betting promotion. Theoretically, individuals with a heightened sensitivity to rewards, such as problem gamblers (Jiménez-Murcia et al., 2016; Navas et al., 2017), may be especially attracted to increased odds promotions. The promotion's higher payouts may lead to the desirability bias, where people tend to choose and overestimate the likelihood of highly desirable outcomes (Windschitl et al., 2013). However, some studies indicate that adolescents and young adults are predisposed to engage in high-risk, high-reward behaviours due to their perceived invulnerability to the risks associated with these behaviours (Hill et al., 2011; Lapsley & Hill, 2009). As such, it is possible that younger people might neglect the potential risks of making high-risk bets with increased odds incentives in light of their higher payouts. Furthermore, the current study revealed that while 50.8% of young people considered the increased odds incentive as a means to increase their earnings, 37.7% reported that the promotion increased their chances of winning. This confusion was also noted by Killick and Griffiths (2020), who used a sample of current gamblers. Individuals may mistakenly believe that the increased odds promotion enhances both the likelihood of winning and the potential earnings from the wager, thereby providing a dual benefit. To combat this, one potential policy solution could be to substitute the language used for “increased odds” or “enhanced odds” promotions with phrases such as "increased payouts" or "better winnings."

The fine print accompanying such offers often includes conditions that diminish their appeal. For example, the fine print of the stake-back promotion stipulates that the stake-back will be provided as bet credits that must be wagered before the bettor can withdraw them, and only the winnings from that wager can be converted into withdrawable credits. Consequently, the stake-back entails more risk than it initially appears. This underscores the importance of bettors carefully reviewing the terms and conditions of betting promotions before participating in order to fully understand the details of the promotion. This prompted further investigation into the extent to which participants read the fine print of betting inducements. The study revealed that 46.2% of participants read the terms and conditions of each betting promotion, while 30.8% read some of the terms and conditions, and 23.1% read none at all. These findings indicate that some people neglect to read the terms and conditions of promotions. However, it is essential to consider that the study results may not be directly applicable to real-life situations because the participants did not face any financial consequences for failing to read the terms and conditions.

Strengths and Limitations

The present study utilised a direct measure of sports betting inducement exposure to enhance the ecological validity of its results. This approach has not been commonly utilised in the current literature (Di Censo et al., 2023b). In addition, we followed Geuens and De Pelsmacker's (2017) recommendation to use researcher-created advertisements, which sought to mitigate the influence of pre-existing brand preferences that could introduce response bias when using examples of real promotional advertising.

The study’s limitations pertain to its inability to consider contextual factors related to sports betting advertising in real-world settings. For example, promotions are often tied to an upcoming sporting event, which could not be captured in the current study. In addition, the current study could not account for the time-sensitive nature of real sports betting promotions, which may have a greater impact on individuals, particularly young people (Przybylski et al., 2013), due to fear of missing out (FoMO). Additionally, the study investigates how young people perceive that sports betting inducements could influence their behaviour rather than measuring their actual behaviour, which could potentially differ. The participants in this study were selected from an online research panel. The individuals who participate in these panels are a specific subset of the general population. This can introduce sampling bias and potentially compromise the external validity of the results. Finally, because the current study lacks a control condition, it should be considered preliminary evidence on which future studies can be built. Future research should consider an experimental design with a control group, such as a brand awareness advertisement with no incentives (e.g., the brand logo and slogan). This would make it possible to draw conclusions about whether promotions with incentives are perceived to have a greater impact on behaviour than promotions without incentives.

Conclusion

The current study demonstrated that among young people, sign-up and bonus bet inducements were perceived as more likely to influence betting behaviour and high-risk betting behaviour compared to increased odds and stake-back promotions. The general trend observed was that promotions with lower costs to the bettor were preferred over those with higher costs. Future research can build on this evidence by employing an experimental design, allowing for conclusions to be drawn regarding whether promotional incentives can influence betting when compared to brand advertising. The results of this study provide evidence in favour of current policies regarding sports betting incentives. Specifically, the findings indicate that promotions offering free bets are the most influential among young individuals.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Aribarg, A., & Schwartz, E. M. (2019). Native advertising in online news: Trade-offs among clicks, brand recognition, and website trustworthiness. Journal of Marketing Research, 57(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022243719879711

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.5.469

Arnett, J. J. (2014). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199929382.001.0001

Australian Communications and Media Authority. (2021a). Communications and media in Australia: The digital lives of younger Australians. Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.acma.gov.au/publications/2021-05/report/digital-lives-younger-and-older-australians

Australian Communications and Media Authority. (2021b). Gambling ads during live sport on broadcast TV and radio. Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.acma.gov.au/gambling-ads-during-live-sport-broadcast-tv-and-radio

Auxier, B., & Anderson, M. (2021). Social media use in 2021. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2021/04/PI_2021.04.07_Social-Media-Use_FINAL.pdf

Bang, H., & Wojdynski, B. W. (2016). Tracking users’ visual attention and responses to personalized advertising based on task cognitive demand. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 867–876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.025

Blain, B., Richard Gill, P., & Teese, R. (2015). Predicting problem gambling in Australian adults using a multifaceted model of impulsivity. International Gambling Studies, 15(2), 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2015.1029960

Boyland, E., Thivel, D., Mazur, A., Ring-Dimitriou, S., Frelut, M.L., & Weghuber, D. (2020).Digital food marketing to young people: A substantial public health challenge. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism,76(1), 6–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000506413

Browne, M., Hing, N., Russell, A. M. T., Thomas, A., & Jenkinson, R. (2019). The impact of exposure to wagering advertisements and inducements on intended and actual betting expenditure: An ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(1), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.10

Bunn, C., Ireland, R., Minton, J., Holman, D., Philpott, M., & Chambers, S. (2018). Shirt sponsorship by gambling companies in the English and Scottish Premier Leagues: Global reach and public health concerns. Soccer & Society, 20(6), 824–835. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2018.1425682

Byrnes, J. P., Miller, D. C., & Schafer, W. D. (1999). Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125(3), 367–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.3.367

Di Censo, G., Delfabbro, P., & King, D. L. (2023b). The impact of gambling advertising and marketing on young people: A critical review and analysis of methodologies. International Gambling Studies, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2023.2199050

Chandran, S., & Morwitz, V. G. (2006). The price of “free”-dom: Consumer sensitivity to promotions with negative contextual influences. Journal of Consumer Research, 33(3), 384–392. https://doi.org/10.1086/508439

Cyders, M. A., Littlefield, A. K., Coffey, S., & Karyadi, K. A. (2014). Examination of a short English version of the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale. Addictive Behaviors, 39(9), 1372–1376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.013

Dajah, S. (2020). Marketing through social media influencers. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 11(9). https://doi.org/10.30845/ijbss.v11n9p9

Deans, E. G., Thomas, S. L., Derevensky, J., & Daube, M. (2017). The influence of marketing on the sports betting attitudes and consumption behaviours of young men: Implications for harm reduction and prevention strategies. Harm Reduction Journal, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-017-0131-8

Di Censo, G., Delfabbro, P., & King, D. (2023a). The awareness of sports betting advertising among young people during the 2022 FIFA World Cup. The University of Adelaide.

Djohari, N., Weston, G., Cassidy, R., Wemyss, M., & Thomas, S. (2019). Recall and awareness of gambling advertising and sponsorship in sport in the UK: A study of young people and adults. Harm Reduction Journal, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-019-0291-9

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.41.4.1149

Ferris, J., & Wynne, H. (2001). The Canadian Problem Gambling Index: Final report. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

Fischer, D., & Hills, T. T. (2012). The baby effect and young male syndrome: Social influences on cooperative risk-taking in women and men. Evolution and Human Behavior, 33(5), 530–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2012.01.006

Frey, R., Richter, D., Schupp, J., Hertwig, R., & Mata, R. (2021). Identifying robust correlates of risk preference: A systematic approach using specification curve analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(2), 538–557. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000287

Geuens, M., & De Pelsmacker, P. (2017). Planning and conducting experimental advertising research and questionnaire design. Journal of Advertising, 46(1), 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1225233

Haw, J. (2015). Impulsivity predictors of problem gambling and impaired control. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 15(1), 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-015-9603-9

Hill, P. L., Duggan, P. M., & Lapsley, D. K. (2011). Subjective invulnerability, risk behavior, and adjustment in early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 32(4), 489–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431611400304

Hing, N., Russell, A. M. T., Vitartas, P., & Lamont, M. (2016). Demographic, behavioural and normative risk factors for gambling problems amongst sports bettors. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32(2), 625–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-015-9571-9

Hing, N., Li, E., Vitartas, P., & Russell, A. M. T. (2017a). On the spur of the moment: Intrinsic predictors of impulse sports betting. Journal of Gambling Studies, 34(2), 413–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-017-9719-x

Hing, N., Russell, A. M. T., Li, E., & Vitartas, P. (2018). Does the uptake of wagering inducements predict impulse betting on sport? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(1), 146–157. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.17

Hing, N., Russell, A. M., & Browne, M. (2017b). Risk factors for gambling problems on online electronic gaming machines, race betting and sports betting. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00779

Howe, P. D. L., Vargas-Sáenz, A., Hulbert, C. A., & Boldero, J. M. (2019). Predictors of gambling and problem gambling in Victoria. Australia. Plos One, 14(1), e0209277. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209277

Hsiao, C.-H., Tang, K.-Y., & Su, Y.-S. (2021). An empirical exploration of sports sponsorship: Activation of experiential marketing, sponsorship satisfaction, brand equity, and purchase intention. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.677137

IBM Corp. (2021). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 28): IBM Corp.

Jiménez-Murcia, S., Fernández-Aranda, F., Mestre-Bach, G., Granero, R., Tárrega, S., Torrubia, R., Aymamí, N., Gómez-Peña, M., Soriano-Mas, C., Steward, T., Moragas, L., Baño, M., del Pino-Gutiérrez, A., & Menchón, J. M. (2016). Exploring the relationship between reward and punishment sensitivity and gambling disorder in a clinical sample: A path modeling analysis. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(2), 579–597. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-016-9631-9

Kaspar, K., Weber, S. L., & Wilbers, A.-K. (2019). Personally relevant online advertisements: Effects of demographic targeting on visual attention and brand evaluation. PLoS ONE, 14(2), e0212419. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212419

Ki, C.-W., Cuevas, L. M., Chong, S. M., & Lim, H. (2020). Influencer marketing: Social media influencers as human brands attaching to followers and yielding positive marketing results by fulfilling needs. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102133

Killick, E. A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). A thematic analysis of sports bettors’ perceptions of sports betting marketing strategies in the UK. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(2), 800–818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00405-x

Kim, D. Y., & Kim, H.-Y. (2022). Social media influencers as human brands: An interactive marketing perspective. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 17(1), 94–109. https://doi.org/10.1108/jrim-08-2021-0200

Lapsley, D. K., & Hill, P. L. (2009). Subjective invulnerability, optimism bias and adjustment in emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(8), 847–857. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9409-9

Martínez-López, F. J., Anaya-Sánchez, R., Fernández Giordano, M., & Lopez-Lopez, D. (2020). Behind influencer marketing: Key marketing decisions and their effects on followers’ responses. Journal of Marketing Management, 36(7–8), 579–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257x.2020.1738525

National consumer protection framework for online wagering in Australia. (2022). Australian Government Retrieved from https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/05_2022/national-policy-statement-updated-3-may-2022.pdf

Navas, J. F., Billieux, J., Perandrés-Gómez, A., López-Torrecillas, F., Cándido, A., & Perales, J. C. (2017). Impulsivity traits and gambling cognitions associated with gambling preferences and clinical status. International Gambling Studies, 17(1), 102–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2016.1275739

Newall, P. W. S., Thobhani, A., Walasek, L., & Meyer, C. (2019). Live-odds gambling advertising and consumer protection. Plos One, 14(6), e021687. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216876

Newall, P. W. S., Ferreira, C. A., Sharman, S., & Payne, J. (2022). The frequency and content of televised UK gambling advertising during the men’s 2020 Euro soccer tournament. Experimental Results, 3. https://doi.org/10.1017/exp.2022.26

Pascucci, F., Savelli, E., & Gistri, G. (2023). How digital technologies reshape marketing: Evidence from a qualitative investigation. Italian Journal of Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43039-023-00063-6

Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841–1848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014

Rockloff, M., Browne, M., Hing, N., Thorne, H., Russell, A., Greer, N., Tran, K., Brook, K., & Sproston, K. (2020). Victorian population gambling and health study 2018–2019. Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation. https://responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au/resources/publications/victorian-population-gambling-and-health-study-20182019-759/

Rolison, J. J., Hanoch, Y., Wood, S., & Liu, P.-J. (2014). Risk-taking differences across the adult life span: A question of age and domain. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 69(6), 870–880. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbt081

Russell, A. M. T., Hing, N., Browne, M., & Rawat, V. (2018a). Are direct messages (texts and emails) from wagering operators associated with betting intention and behavior? An ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(4), 1079–1090. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.99

Russell, A. M. T., Hing, N., Li, E., & Vitartas, P. (2018b). Gambling risk groups are not all the same: Risk factors amongst sports bettors. Journal of Gambling Studies, 35(1), 225–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-018-9765-z

Shampanier, K., Mazar, N., & Ariely, D. (2007). Zero as a special price: The true value of free products. Marketing Science, 26(6), 742–757. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1060.0254

Smit, E. G., Van Noort, G., & Voorveld, H. A. M. (2014). Understanding online behavioural advertising: User knowledge, privacy concerns and online coping behaviour in Europe. Computers in Human Behavior, 32, 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.11.008

Stenstrom, E., Saad, G., Nepomuceno, M. V., & Mendenhall, Z. (2011). Testosterone and domain-specific risk: Digit ratios (2D:4D and rel2) as predictors of recreational, financial, and social risk-taking behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(4), 412–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.07.003

Thomas, S., Pitt, H., Bestman, A., Randle, M., Daube, M., & Pettigrew, S. (2016). Child and parent recall of gambling sponsorship in Australian sport. Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation. https://responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au/resources/publications/child-and-parent-recall-of-gambling-sponsorship-in-australian-sport-67/

Thomson, M. (2006). Human brands: Investigating antecedents to consumers’ strong attachments to celebrities. Journal of Marketing, 70(3), 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.70.3.104

Trimpop, R. M. (1994). The psychology of risk taking behavior. North-Holland.

Twenge, J. M., Martin, G. N., & Spitzberg, B. H. (2019). Trends in U.S. Adolescents’ media use, 1976–2016: The rise of digital media, the decline of TV, and the (near) demise of print. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 8(4), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000203

Wilde, G. J. S. (1982). The theory of risk homeostasis: Implications for safety and health. Risk Analysis, 2(4), 209–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.1982.tb01384.x

Wilson, M., & Daly, M. (1985). Competitiveness, risk taking, and violence: The young male syndrome. Ethology and Sociobiology, 6(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/0162-3095(85)90041-x

Windschitl, P. D., Scherer, A. M., Smith, A. R., & Rose, J. P. (2013). Why so confident? The influence of outcome desirability on selective exposure and likelihood judgment. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 120(1), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2012.10.002

Wojdynski, B. W. (2016). The deceptiveness of sponsored news articles. American Behavioral Scientist, 60(12), 1475–1491. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764216660140

World Health Organization. (2019). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11 ed.) https://icd.who.int/

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions This research was conducted as part of a PhD scholarship, awarded to Gianluca Di Censo, funded by the NSW Government’s Responsible Gambling Fund, and supported by the NSW Office of Responsible Gambling.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study idea was conceived by G.D and P.D. G.D wrote the manuscript and received support from P.D. The final version of the manuscript was edited by D.L.K. G.D is a doctoral candidate who is under the supervision of P.D and D.L.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Di Censo, G., Delfabbro, P. & King, D.L. Young People’s Perceptions of the Effects and Value of Sports Betting Inducements. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01173-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01173-0