Abstract

There is a substantial body of evidence on the construct of personal recovery and the value of recovery-oriented mental health care worldwide. Personal recovery refers to the lived experience of those with mental illness overcoming challenges and living satisfying lives within the limitations of mental health symptomology. Conceptualisations such as CHIME have primarily relied on adult frameworks. With growing concerns about youth mental health, the present study aimed to understand the experiences of personal recovery and recovery-oriented care for youth. Given the multisystemic influences on youth development, the study analysed narratives from youth, caregivers, and mental health professionals. The analysis revealed two developmentally unique recovery processes involving the restoration of capabilities and existing relationships (restorative processes) and the bolstering of protective influences and strengths (resilience processes). Deductive analysis identified alignment to the CHIME framework. Implications of the findings for recovery-oriented care for youth are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Epidemiological studies highlight that increasing numbers of youth (aged 15 to 24 years) experience poor mental health (MH), with between 20 and 25% of young people diagnosed with MH disorders and 50% of adult MH disorders originating during adolescence (Burns et al., 2016; Ward, 2014). The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly increased the number of youth experiencing anxiety and depression, with the current global prevalence estimated to be at 25.2% and 25.5%, respectively (Racine et al., 2021). Although several MH conditions experienced in youth are treatable through evidence-based interventions (Barry et al., 2013; Clarke et al., 2014; Das et al., 2016), young people continue to experience challenges and barriers in accessing support within existing MH care systems (McGorry et al., 2022). Scholars have described youth MH services as “shoehorned” onto existing medical systems that are primarily designed to meet the needs of those with physical illnesses (McGorry et al., 2022). This has resulted in MH services often adopting a narrow focus on reducing psychiatric symptoms. Current models of MH care fall short of engaging youth, particularly those with complex social-emotional difficulties (Gibson, 2021; Rickwood et al., 2007).

In response to similar challenges in the adult MH care system, global MH services have begun to shift toward recovery-led programs as best practice (Slade et al., 2014; Zuaboni et al., 2017). Personal recovery refers to a process whereby individuals live meaningful, hopeful, rewarding, and satisfying lives, with or without the presence of ongoing MH symptoms (Anthony, 1993). Personal recovery is distinguished from traditional notions of clinical recovery (symptom remission) and functional recovery (e.g. return to work or study). Recovery-oriented MH services focus on promoting well-being, self-management, and improved community participation and have led to the co-design and co-delivery of adult MH programs and facilities through collaborations between MH professionals and individuals with lived experience of MH concerns (Sommer et al., 2018; Whitley et al., 2019).

Leamy et al. (2011) propose a framework of five key processes related to personal recovery. The processes correspond to the acronym CHIME, referring to social connectedness (Connectedness), hope and optimism about the future (Hope), transforming identity (Identity), finding meaning and purpose (Meaning), and empowerment in self-management of functioning and MH concerns (Empowerment). Figure 1 provides further information regarding each of these domains. The CHIME model of recovery has developed a large body of evidence to support its utility in informing clinical and research programs and is frequently cited as the model of choice for defining and investigating recovery in MH (Buchanan et al., 2014; Hurst et al., 2022; Perkins & Slade, 2012; Slade, 2012; Slade & Longden, 2015; Whitley et al., 2019). However, most of the research linked to CHIME has been conducted within adult populations, and it remains unclear if the model suits youth.

Processes of adult recovery (CHIME; Leamy et al., 2011)

Efforts to understand recovery in youth have adopted an ecological view of recovery (Kelly & Coughlan, 2019; Rayner et al., 2018). According to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, human development consists of a series of interrelated systems that encompass the ecology of human life and provide an environment in which the biological and psychological are influenced during the growth of the individual (Crawford, 2020). Building on this ecological-systems approach, recovery-oriented systems of care (ROSC) models represent an integrated system of care and support for youth and their families, as well as key stakeholders across contexts and settings (Berger, 2018; Davidson et al., 2021; Piat et al., 2010; Sheedy & Whitter, 2013; Walsh et al., 2019). This wrap-around care approach includes support for youth through various stages of recovery, education to promote health literacy for youth, families, and other stakeholders, and services related to prevention and MH promotion (Davidson et al., 2021). ROSC models have been utilised extensively with youth substance abuse support, with limited evidence for use in youth MH service.

In a qualitative focus group-based study investigating CHIME processes in child and adolescent MH services in Australia, Naughton et al. (2020) explored the perspectives of MH professionals and how routine MH care processes align with CHIME processes. While the study supported the utility of the CHIME framework, it also highlighted the need to capture the critical role played by family and friends in the recovery process for youth. The results also highlighted the dynamic, developmental needs of youth across different ages, and the need for a framework of recovery that captures how these developmental challenges may influence CHIME processes, and the provision of recovery-oriented care. The authors recommend future research to incorporate the view of youth and families in further expanding CHIME processes.

In summary, there is growing consensus for providing recovery-oriented, holistic, and ecological systems approaches to youth MH care. A shared conceptual framework of youth recovery between youth, families, education, health, MH, and other community-based supports may support the provision of integrated, biopsychosocial care across contexts. The present study aims to understand CHIME processes through consultations with youth, families, and other stakeholders across key contexts on personal recovery and recovery-oriented care for youth with MH concerns.

Methods

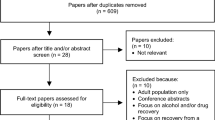

A hermeneutic phenomenological qualitative design was employed to explore the lived experience narratives of professionals working in youth mental health treatment facilities and young people living with mental health symptoms and their recovery. Focus group methodology and semi-structured interviews combined with thematic analysis were used to develop a rich interpretation of recovery for youth. This data was collected from workshop discussions and interviews with professionals, youth, and caregivers from a state-run youth MH facility in Queensland, Australia. Participants’ contributions throughout the focus groups and interviews were de-identified during transcription. Participants were also encouraged to reflect on the questions prior to data collection and, in the case of focus groups, provide further information via online surveys consisting of the same questions discussed within the focus groups. Ethics approval was obtained through the University of Southern Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (H20REA100) as part of a larger program of research. Figure 2 provides a structure of the data collection process.

Participants

Participation was voluntary. All participants completed consent forms and were provided with written information detailing the nature of the study. Participants under the age of 18 years were also required to provide parental/guardian consent. Participants were informed that focus groups and interviews would be audio/video recorded before participation. All data collection was conducted between 6 September 2020 and 4 August 2021.

MH Professionals

MH professionals with expertise working with youth populations participated in the research. Professionals were contacted through personal communications, email invitations, and flyer advertisements distributed through local child and youth MH services. MH professionals working in three youth public MH services in Queensland, Australia, were offered the opportunity to participate due to their experience with youth mental health and the recent systemic move to recovery-oriented care. One location agreed to participate in the study. Participants were purposefully selected from each professional discipline employed within the team at the adolescent extended treatment facility: medical physicians, clinical psychology, nursing, education, lived experience, consumer and carer support, and allied health. Each area offered at least one participant. Purposive sampling was used to ensure a holistic view of care within the multidisciplinary team. Participants in this group participated in the focus group.

The first focus group consisted of 12 participants, while the second consisted of 10 participants (see Table 1). Each participant had a minimum of 3-month experience working within the facility supporting youth MH and most had additional experience prior to their current role. Support included case management, intervention, education support, and recovery-oriented care. Participants were invited to review the focus group questions via a survey before attending the focus group to allow for reflection and anonymous contribution before group data collection. Participants did not receive reimbursement for their participation.

Procedure for Focus Groups

Focus groups were chosen as the mode of data collection to reduce the impact of participation time on the treatment centre and researchers, and to allow the group to collaborate on their perspectives and recovery-oriented approach. Focus groups were conducted with the professional participants to explore a variety of views regarding youth recovery; questions were broad to allow for novel themes to emerge. Both focus groups were audio-recorded, and field notes were taken. Both were held at a state-run youth MH facility in Queensland, Australia, and occupied a 4-h duration.

On arrival, the researchers introduced themselves and offered the opportunity for group introductions. Participants were provided with an overview presentation of the research project and core constructs (e.g. recovery, youth recovery, CHIME framework; Leamy et al., 2011) to ensure a common understanding of the key concepts. The research team developed a series of five questions that followed the presentation in focus group one (see Table 7 in Appendix 1). Questions focused on experiences of youth recovery and identifying what would be key program elements and priority areas for personal recovery education for youths. Focus group 2 participants were also provided with an overview presentation of the results from focus group 1. Participants were asked to discuss the barriers and enablers of youth recovery. In each group, participants were separated into smaller groups of three to five participants to ensure they had an opportunity to express their views and opinions within the allocated time. Each of the smaller groups was facilitated by either a research team member or a clinical lead nominated as a temporary moderator. An opportunity to debrief and to provide any additional thoughts was offered in the last 30 min of the focus groups after participants were reconnected.

Youth and Caregivers

All participants were contacted via personal communications, email invitations, and flyer advertisements distributed throughout local MH service networks, health consumer advocacy groups, and professional networks. Interviewees were provided a copy of interview questions and research project information before the interview to allow for reflection. Interview participants were eligible to receive remuneration consisting of retail vouchers ranging from $20 to $100 via a random draw. A purposive sample of 16 youth (10 inpatients) and 9 caregivers of youth who had experienced MH concerns (including three caregiver/child dyads; see Tables 2 and 3) were included in the study. All caregivers were parents of the participants.

Procedure for Interviews

Interviews were used to explore a variety of views regarding youth recovery and questions were broad and not inclusive of the word recovery to allow for novel themes to emerge. Interviews were the chosen mode of data collection for youth and caregivers to support anonymity, confidentiality, and willingness to covey authentic experiences and thought processes in a safe and private environment. All interviews were audio-recorded, and field notes were taken. Interviews were held at a state-run youth public health service facility in Queensland, Australia, at participants’ homes, or via phone, and ranged between 20 and 90 min in duration. Following initial introductions, participants were asked to answer a series of four (youth) or five (caregivers) questions developed by the research team (see Table 8 and Table 9 in Appendices 2 and 3, respectively). Questions focused on the recovery experience for youth and caregiver views on youth recovery. Interview questions were developed by the research team in an iterative process and based on data from the focus groups. After the interview, an opportunity to debrief and provide any additional thoughts was offered.

Data Analysis

A total of 27 h and 43 min of focus group and interview material were analysed using a hermeneutic phenomenological qualitative design to integrate professional and lived experience perspectives relevant to youth MH. Both inductive and deductive thematic analysis techniques were used to uncover the relevance of CHIME to youth MH and recovery. Analysis followed the six steps outlined by Braun and Clarke (2021). Focus groups and interviews were audio-recorded on the day and transcribed verbatim by one of the researchers. The recordings were listened to several times, while transcribed data and field notes were read, re-read, and checked against recordings for accuracy. The coding of data was conducted by three researchers (also authors) using NVivo 12 Pro. Each researcher worked individually to encode all information and produce themes and sub-themes. The coding of data and themes was then reviewed collectively in an iterative process until consensus was met between researchers on key themes and sub-themes. Focus group and interview data were originally coded separately and later combined as data codes and themes were similar across both data sets.

Findings

The qualitative data analysis revealed several similarities in themes identified across stakeholders. Given these similarities, themes identified across all the stakeholders are presented together. The thematic analysis identified 11 themes, ten categorised into two groups. Each of the two groups (consisting of five themes each) relates to two recovery-oriented processes: restorative and resilience processes. The themes from the research are displayed in Table 4. Themes and sub-themes are discussed in detail below.

Youth Recovery as a Process

Importance of Language and Terminology

Participants across all groups emphasised the importance of language and terminology when referring to concepts of recovery in youth. The need for developing a new, shared vocabulary and framework of understanding was highlighted—a clear departure from the dominant, medical model conceptualisation of clinical recovery (i.e. management and remission of MH symptoms). Similarly, caregivers highlighted the risks of not clarifying recovery among youth as a process distinct from changes in MH-related symptoms. It was highlighted that without such explicit distinctions, adults could inadvertently pathologise normative developmental needs and behaviours of youth, particularly the needs for autonomy and belonging.

…if you’re going to talk in medical language, it’s not appropriate. But you don’t want it too child-like either…because you’re in that interesting phase where they still need to have support, but they still need to be able to express themselves… (parent)

Youth discussed how the term recovery when used in MH contexts seemed to have a deficit focus—implying a loss of capacity or ability, and that recovery involves a return to a more normative standard of functioning and well-being.

I actually don’t like the word recovery because it implies that there’s a recovered point. Like this point where you’re no longer sick anymore or whatever, but realistically, there isn’t a final point. You just keep going, you know. (youth)

All stakeholders highlighted the need to clarify the term recovery, particularly in policies and documents that contain clinical language.

Unique and Non-linear

Caregivers highlighted the need to distinguish between understanding recovery as a process or journey, rather than a distinct state of being, or clinical status. The findings show this distinction is essential for youth and families with chronic and complex MH concerns and social needs. Professionals discussed recovery as a process of living “alongside” MH concerns, rather than “overcoming or extinguishing” such difficulties. The clarification of this concept in future research may help develop realistic expectations regarding recovery—a non-linear and challenging process for youth and their support networks.

…There will still be times when your symptoms are a bit more extreme than other times. Symptoms are still going to happen every now and then, but you’re still getting better, and it happens a little bit less… (youth)

Restorative Processes

Restoration has been defined as the process of recovery from a depleted psychological, physiological, or social resource (Hartig et al., 2003). Theories of restoration in mental health have attempted to explain how a restorative environment can improve mental well-being by utilising existing, untapped resources and reinstating qualities of the environment that contribute to the process of reducing the impact of stress, mental fatigue, and negative emotions (R. Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989; S. Kaplan, 1995). While theories of mental restoration have primarily focused on aspects of the physical environment (e.g. the impact of being in natural spaces), the present analysis highlighted the aspects of the relational and emotional contexts that promote a sense of safety and restoration in the personal recovery of youth. Sub-themes related to restorative processes and exemplary quotes are presented in Table 5.

Re-establishing or Affirming Relationships with Family and Friends

A large body of research identified the critical role of supportive, stable, and reciprocal relationships with family and friends in protecting at-risk youth from mental health disorders (Demaray & Malecki, 2002; Warren et al., 2009) and in reducing the chronicity and impairment for youth with diagnosed psychiatric disorders (Geller et al., 2008; Meadows et al., 2006). While developmental theories (Erikson, 1980) posit the reducing importance of family relationships in the process of individuation in youth, findings highlight the importance of these close relationships in the youth recovery process. Similar to normative youth development, however, youth with mental health concerns are required to develop increasingly sophisticated interpersonal skills (Preyde et al., 2019). For youth with mental health concerns, these findings show that developing these social skills might occur with family members and caregivers who may have depleted psychological resources related to competing demands and unmet personal needs. In addition, research indicates that stigmatising beliefs related to mental health may lead to heightened proneness to shame and frustration in youth and their families (Goffman, 1963). Participants discussed these contexts as contributing to coercive cycles of family interactions that interfere with the recovery process. This research has shown that breaking these cycles of negative interactions requires therapeutic guidance. For younger youth (aged 15–16 years), caregivers and mental health professionals highlighted the need for family therapy (Jiménez et al., 2019), focusing on building dyadic interaction skills for caregivers. With older youth (aged 17–24 years), youth highlight the need for interpersonal skills training in resolving conflict (see quote in Table 5). While reconnection and restoration of such relationships may be complex and challenging for some youth, these finding show supports appear necessary for recovery.

Developing Hopeful Expectations of Oneself, Others, and the Recovery Processes

All participants highlighted hope as an integral component of youth recovery. Similar to adults, feelings of hope in the face of complex developmental challenges can buoy youth and their families and can be fostered by professionals, social supports, and mental health service systems (Khoury, 2019). Youth in this study reported a loss of hope and vision for the future during difficult times. They highlighted the value of listening to stories of personal recovery from other youth with lived experiences of mental health and how this helped to restore hope in both themselves and the future (see quote in Table 5). Youth accessed stories of lived experience through the Internet (from websites like youtube.com or social media applications like TikTok) and interactions with peer-support and lived experience practitioners. Peer support is a reciprocal relationship that involves someone with lived experience of mental health and life challenges supporting and advocating for someone with mental health concerns (Mahlke et al., 2014). Best practice peer support is recovery-oriented and reciprocal; it involves sharing recovery experiences and emphasises individual strengths and hope (Mahlke et al., 2014). While research on peer support with youth is emerging (Tisdale et al., 2021), evaluations of these supports in adults with mental health concerns strongly support its efficacy in increasing feelings of hope (Mahlke et al., 2014). Caregivers in the present study highlighted the power of accessing stories of youth mental health and their families as beneficial in maintaining a hopeful outlook and supporting youth in the face of setbacks.

Exploring Identification with Family, Friends, Community, and Culture

Erikson’s theorising on identity formation in youth has provided the foundation for most identity research (Cote & Levine, 2014). Erikson (1950) described identity formation in youth as a process of sorting through various potential alternatives (exploration) before settling on one or more of these (commitment). Exploration and commitment dimensions are each divided into “presence” versus “absence”. The dimensions create four statuses: achieved (commitments enacted following exploration), moratorium (active exploration without commitments), foreclosure (commitments enacted without prior exploration), and diffusion (lack of commitments or attempts to explore; Kroger & Marcia, 2011). Extensive literature provides evidence that youth in the achieved status appear to be better adjusted and self-directed than those in the other statuses (Kroger & Marcia, 2011). While youth with mental health concerns may be at any of these stages of identity formation, participants in this study highlighted the impact of mental health-related stigma concerns on developing a positive identity among youth. Perceived stigma relates to their (a) perceptions that society generally devalues and discriminates against people who have a mental illness (Link et al., 1989) and/or (b) perceptions that others discriminate against or devalue oneself because of problems or labels. Among adults, perceived stigma is associated with poorer treatment outcomes, smaller and less supportive social networks, as well as shame, and lower self-esteem and sense of agency (Corrigan & Watson, 2002; Perlick et al., 2001). In contrast to the sizeable literature on adults’ stigma experiences, knowledge about the subjective stigma experiences among youth with mental health concerns is sparse (Hinshaw, 2005). This is unfortunate as stigma may be challenging for youth to cope with given their age-related problems, including a preoccupation with social image, peer acceptance, and identity consolidation (Bulanda et al., 2014; Heflinger & Hinshaw, 2010). Participants in the study described overcoming this stigma and developing a positive identity as requiring youth to actively challenge negative stereotypes and beliefs about mental health and integrate their difficulties into a positive sense of self. Additionally, this study showed that the recovery process included youth attending to aspects of their identity outside of their mental health concerns—relating to aspects of their culture and community.

Grieving Losses and Missed Milestones

Participants identified experiences of loss through their recovery journey, including the loss of relationships, schooling or educational attainment, belonging, control, or an imagined future (Doka, 1989). The descriptions of these losses aligned with conceptualisations of ambiguous, symbolic, and disenfranchised losses (Bauman, 2022; Corr & Corr, 2012; Doka, 1989; Mitchell, 2017). Symbolic losses refer to psychosocial losses, such as the loss of belonging or plans for the future (Mitchell, 2017). Ambiguous losses often occur in relationships and can involve the psychological or physical absence of friends or family (Mitchell, 2017). Youth in this study reported the ambiguous loss of relationships with close family and friends, through their recovery journey. For example, one youth described a loss of belonging at school and felt alienated by teachers and school peers, which caused him to retreat. Poor academic performance due to mental health often arises from low attendance due to treatment-seeking or school refusal and can lead to further symbolic losses related to an imagined future (Rayner et al., 2018; Rowling, 2012). Several participants highlighted the importance of identifying and grieving disenfranchised losses in recovery. Disenfranchised losses are not acknowledged or validated due to their lack of visibility or associated stigma (Bauman, 2022; Corr & Corr, 2012; Doka, 1989; Mitchell, 2017). Disenfranchised grief can occur when the loss is not understood, the circumstances involve a stigmatised condition, the expression of grieving is unexpected, or the griever’s capacity to grieve is undervalued, such as for youth (Bauman, 2022). While grief is not a process included in the CHIME framework, it appears to align most closely with the meaning-making recovery process. Data from the study highlights the importance of acknowledging and validating losses for youth while providing a space to grieve and engage in adaptive meaning-making (Table 5).

Accepting Assistance and Support

Participants spoke of the process of restoring youth’s trust in social support and services as a key aspect of recovery. Hall et al. (2001) define trust as “optimistic acceptance of a vulnerable situation in which the truster believes the trustee will care for the truster’s interests” (p. 615). While participants described the lack of trust and engagement as being linked to the limited benefits experienced by the youth from previous dealings, participants described the process of seeking assistance and support as triggering in youth stigmatising beliefs related to mental health. To avoid this additional source of mental distress, youth in this study showed reluctance to seek help from services that excessively focus on their deficits and needs. Caregivers and professional discourse described recovery-oriented care as requiring an explicit focus on the youth’s strengths, interests, and preferences. Caregivers spoke of this process of “doing with, not doing to” as promoting self-efficacy and responsibility in youth in meeting developmental challenges and managing mental health concerns. When professionals held a non-stigmatising stance and aimed to build on existing capabilities, youth described themselves as more likely to engage in services and be empowered to be active agents in their recovery—rather than passive recipients of care.

Resilience Processes

Resilience is a dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity (Luthar et al., 2000). This research demonstrated that from a developmental perspective, supporting positive adaptations among youth with mental health concerns relates to restoring support and a sense of belonging (restorative processes) while promoting individuation and developmental capabilities for independence. In this regard, findings showed that resilience processes amplify strengths and abilities and facilitate opportunities for exploration and growth. Participants described resilience processes as “making up for lost time”—allowing youth to engage in normative developmental experiences and not deprived of such opportunities due to excessively risk-averse restrictions related to managing their mental health concerns. Theoretical comparisons of resilience and recovery have found them to be distinct but related concepts (Friesen, 2007). The qualitative data analysis highlights recovery in this developmental stage as involving experiences that fortify the strengths and capabilities of youth to prepare them for the challenges of adulthood. Table 6 displays sub-themes and quotes related to reliance processes.

Developing New Friendships and Connections

Participants spoke of the importance of youth developing a sense of belonging outside their families. Mental health concerns, and the related demands of therapeutic interventions, were described throughout participant discourse as depriving youth of developmental opportunities for building new relationships. With social relationships becoming increasingly complex and requiring increasingly sophisticated social skills, participants described a pattern of withdrawal and avoidance among youth who are often overwhelmed by these demands and/or have had painful experiences of rejection or ostracism. The distress related to negative relational experiences may be heightened by self-stigmatising attitudes related to mental health (Carrara & Ventura, 2018; Gerlinger et al., 2013; Hartman et al., 2013; Tang & Wu, 2012). Youth highlighted that connecting with other youth with mental health concerns (or those with a lived experience of mental health difficulties) was often a helpful place to start. Youth discourse showed that listening to lived experiences of mental health appeared to alleviate self-stigmatising attitudes, provide a sense of belonging for the youth, and shape realistic beliefs about discriminatory and stigmatising beliefs held by the public. Participants described these cognitive and motivational changes as integral in helping youth develop the courage to attempt to form new relationships. Caregivers and mental health professionals spoke of the importance of scaffolding youth when trying to build new relationships—shaping realistic expectations of interactions, coaching them on using social skills, and helping them cope with any perceived failures (Table 6).

Holding an Optimistic View of the Future

Two distinct sub-themes emerged from the data on the role of hope in resilience building for the future. Caregivers and youth continuing to face acute mental health concerns (e.g. ongoing self-harm, low mood, suicide attempts) fostered hope from celebrating progress and “small wins” towards social-emotional or education-based goals. The perception of “moving forward” was crucial in building youth’s self-efficacy and hope. Mental health professionals spoke of being “on the lookout” for signs of progress and achievements—to build a repository of anecdotes to shape positive expectations for the future and challenge feelings of hopelessness amongst youth and their families. For youth who may have experienced periods of stability in their mental health and living circumstances, these findings demonstrated that hope was fostered by establishing goals and aspirations for the future. Most goals in this cohort were related to education (e.g. going to university) or vocational (e.g. getting a part-time job) goals. Youth also spoke of goals about mental health self-management (e.g. days without self-harming) and meaningful relationships (e.g. being in a romantic relationship).

Exploring Affiliation with New Communities

Erikson (1968) described identity as a fundamental organising principle that constantly develops throughout the lifespan. Identity provides a sense of continuity within the self and in interaction with others (“self-sameness”), as well as a frame to differentiate between self and others (“uniqueness”), which allows the individual to function autonomously from others (Erikson, 1968). The restorative process found within this study related to identity focused on youth gaining “self-sameness”—by developing adaptive, non-stigmatising beliefs about their mental health concerns, families, culture, and communities. In contrast, these findings showed that resilience processes offer youth opportunities for differentiation by acknowledging their identity as being multifaceted and their mental health concerns as only one part of the whole. Participants in the study spoke of the importance of new peer groups and communities (both on the internet and in person) influencing the exploration of new identities. This is consistent with research on youth that highlights how peer groups provide emotional support for youth and a social status necessary for identity development to occur (Nawaz, 2011). Caregivers spoke of the need to be “accepting” of youth experimenting with new and unique identities and allowing space for youth to learn from these experiences. Health professionals and caregivers spoke of keeping in mind their personal history of identity formation (e.g. “I remember dressing like a goth and disappearing into my room for hours”). They described efforts to minimise risks for the youth of anti-social influences, while not depriving them of these developmental experiences.

New Values and a Sense of Purpose

Values are desirable trans-situational goals (expressed as preferred behaviours) that serve as guiding principles in people’s lives (Bilsky & Schwartz, 1994). The relative priority that people assign to values strongly influences their behaviour in enduring and significant ways (Bilsky & Schwartz, 1994). The findings demonstrated that the process of individuation and differentiation requires youth to question the values and priorities of their families. Participant discourse showed that for those experiencing mental health concerns, the recovery process often prompts an evaluation of the values and beliefs of the broader society—particularly regarding dominant, commonly held, stigmatising beliefs about mental health. Participants in the study described how this newly gained insight into misperceptions, inequities, and consequences of discriminatory systems offers youth a sense of purpose and mission for the future. Similar to the adult process of meaning, caregivers in this study highlighted the role of religious, spiritual, and existential beliefs in youth recovery and found activities linked to organised religious activities and casual employment as beneficial for youth in maintaining a sense of purpose for the future. Youth spoke of the need for meaningful activities and creative outlets (other than communication) for the existential angst and frustration they sometimes felt. While not all youth were described as able to engage in such adaptive meaning-making, several caregivers spoke of the importance of values and a sense of purpose in helping youth cope with significant setbacks and moments of hopelessness (Table 6).

Learning Skills in Self-regulation and Advocacy

Similar to research on adults, participants spoke of youth developing a greater understanding of mental health and coping through the process of recovery. Mental health professionals spoke of offering opportunities for youth to practice coping skills in potentially challenging situations. Caregivers spoke of the need to manage their personal reactions—including feelings of uncertainty and worry—in allowing youth to manage their mental health concerns independently. Youth described the cumulative benefits of such experiences as contributing to a sense of self-efficacy and agency in shaping meaningful lives—despite the presence of mental health concerns. Findings demonstrated the process of shifting from being a passive recipient of support to being an active agent of change is reflected in youth becoming effective advocates for their needs and equal collaborators in decision-making regarding mental health care. A growing body of research highlights the benefits of shared decision-making and valuing youth voice in the care provided in mental health services (Langer & Jensen-Doss, 2016). Mental health professionals reflected on existing procedures and processes unsuitable for involving youth and caregivers in decision-making. They flagged the need for recovery-oriented care principles to be reflected in policies, procedures, and legislations relating to youth mental health. Caregivers spoke of the need to consistently offer youth and their families an opportunity to contribute to care decisions (e.g. inviting youth and families to care planning meetings). The active participation of youth in these processes was described throughout the data as a sign of recovery and developed capabilities for youth to communicate their needs and preferences in other settings like schools and workplaces in the future.

Discussion

The rising rates of MH concerns for youth have prompted calls for innovative, effective, and non-stigmatising approaches to early intervention. The paradigm of personal recovery offers a compelling alternative to dominant clinical models of mental health. Despite the proliferation of guidance on recovery-oriented care in MH services, particularly in high-resource settings such as Australia, the concept of personal recovery is relatively novel in youth MH. Emerging research on the conceptual frameworks of youth recovery has been primarily informed by either the views of health professionals (e.g. Naughton et al., 2020) or youth (e.g. Rayner et al., 2018) or caregivers (Kelly & Coughlan, 2019). The present study utilised a multisystemic approach to identify a framework of youth recovery that can offer a shared understanding and language across youth and key stakeholders supporting the youth. Building on the extant research on personal recovery, the study also aimed to explore the relevance of CHIME recovery processes (Leamy et al., 2011) for youth. The findings of the qualitative analysis reveal complex developmental challenges and recovery needs of youth with MH concerns.

Overall, narratives across various groups of participants revealed similarities in their views on youth recovery. Previous research has highlighted the differences in the perspectives and priorities of youth, caregivers, and professionals concerning recovery needs (e.g. Law et al., 2020). While narratives in the present study highlighted key differences between and within groups of participants, similarities in the conceptualisation of personal recovery may reflect the growing acceptance, understanding, and shared language regarding recovery in mental health services in countries like Australia. The synthesis of the narratives revealed alignments with the CHIME framework (Leamy et al., 2011). These findings echo those of research conducted by Rayner et al. (2018) and Naughton et al. (2020), who found similar alignments to the CHIME framework in conceptualising recovery and recovery-oriented care for youth. Beliefs about recovery being unique and non-linear appear to also be consistent with findings from the adult literature (Leamy et al., 2011; Mccauley et al., 2015; Piat et al., 2017). While this may suggest that youth may benefit from the support that aligns with recovery-oriented care for adults, the sub-themes identified highlight the unique developmental needs and systemic influences on youth recovery.

Overall, the analysis revealed recovery as involving youth negotiating developmental transitions and building capabilities in managing their mental health. The challenge of these dual goals is influenced by the presence of stigmatising attitudes (held by the public and the youth about themselves), ambiguous losses and disenfranchised grief, and rapidly growing social, academic, and vocational demands. The dual process framework presented in this study is similar to the findings of (Law et al., 2020) conceptualisation of recovery following interviews with 23 youth with mental health concerns in the UK. Law et al. (2020) highlighted the dynamic and fluctuating nature of how youth defined recovery. Based on the severity of mental health concerns and the stage of recovery, meeting the youth’s recovery needs required a balance between three key goals: support vs. independence, acceptance/coping with symptoms vs. reducing symptoms, and discovering self vs. best version of the self. These dialectical recovery goals align with our conceptualisation of restorative and resilience processes. It is possible that the identified CHIME recovery needs corresponding to each of the two processes are on a dialectic (see Fig. 3). In this way, recovery-oriented care could enable practitioners to assess and aim to support a balance between restorative and recovery needs for youth and their families. Further research is required to validate this conceptual model and its utility in promoting personal recovery and recovery-oriented care for youth.

Drawing on developmental and post-modernist theories, this qualitative analysis revealed youth recovery consisting of two related processes: restoration and resilience. Restorative recovery processes address the cumulative impact of adversity and risk factors linked to mental health concerns on the youth, their family, their sense of self, and their beliefs about the future. These processes also restore the internal coping resources (e.g. grieving and building acceptance) and family and mental health service supports (e.g. reconnecting with family and engaging with mental health providers). Many of the elements of restorative recovery processes align with traditional conceptualisations of mental health services and therapeutic supports. While the success of these supports is often assessed through evidence of symptom reduction and improved functioning, these CHIME-related restorative processes offer practitioners a framework to plan and evaluate the impact of their interventions from a recovery lens. While youth may not necessarily report reductions in their presenting mental health concerns, changes in these other recovery domains may serve as progress indicators. This may be particularly pertinent when providing care to hard-to-reach youth with chronic mental health concerns and families with complex needs. Future research into the development of robust measures of youth recovery may aid in the planning, monitoring, and delivering recovery-oriented care.

Resilience processes were found here to relate to bolstering youth’s strengths and protective factors to encourage personal recovery and build capabilities for the future. In addition to self-regulatory and coping skills, resilience processes enabled the development of new networks of support, grappled with new values, philosophical and existential meaning-making, and facilitated skills in advocacy. The role of caregivers and practitioners was described as one involving the facilitation of developmental opportunities and scaffolding the youth in their engagement. Similar to restorative processes, the provision of such support appears to fall within the remit of both clinical (e.g. allied health, nursing) and non-clinical staff (e.g. youth workers, lived experience practitioners). While recovery-oriented care has been promoted as an integral part of all routine care, it remains unclear what specific interventions and practitioner behaviours are linked to each CHIME domain. Future research may develop a taxonomy of recovery-oriented care supports and strategies corresponding to the two processes (restoration and resilience) and key CHIME dimensions. Nevertheless, the framework offers a promising model for greater collaboration and integration of care provided by multidisciplinary staff to youth with mental health concerns.

Study Limitations

Limitations to this study included the number and location of participants, with many coming from metropolitan areas within Queensland. These findings, while relevant, are to be applied with caution as there are several limiting factors to their generalisability. Firstly, they incorporate the views of MH professionals and educators within Queensland Health and are subject to policy and values inherent within this organisation. While participants provided a diverse representation of MH and education professionals, representation was not exhaustive, and some occupational areas were limited to one participant. They are indicative of youth who are aware of and had access to these public health services. They do not offer a global representation of the socio-economic impacts of recovery-oriented care and perspectives as Australia is a high-resource country. The viewpoints of other youth, families, and professionals around Australia and worldwide would add to the credibility of this research. The professional views and opinions represent working with more severe presentations of MH within a public health system. The youth engaged in this research had experienced more severe MH concerns. Understanding how recovery applies to more general and moderate presentations of MH concerns would add to this research. Finally, they do not adequately represent marginalised populations and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth. These limitations highlight the need for further recovery research among youth populations.

Implications for Practice and Future Research

Participants identified specific ways youth and their families can be supported within the recovery process. This included sharing experiences of recovery from peers and lived experience professionals and families engaging in communities of support. Mental health professionals are upskilled in the risks of paternalistic care and guided in providing recovery-oriented care. Family and caregivers must be assisted in understanding recovery and mental health to support their young people. Youth need a safe environment that supports learning and offers the opportunity to witness lived experiences through peers and supports. Supports need to be available when youth need them and need to work together with the youth championing them throughout their recovery journey.

This study demonstrates a need for additional research investigating the recovery-oriented practice and ROSC applied to younger populations. While this and other research have shown that recovery models may apply to younger populations, there is more work to be done in the examination of elements such as language and the importance of systemic perspectives, in particular, the need for further exploration of the perspectives of youth and families with lived experience of MH concerns and personal recovery.

Conclusion

The present study has provided several key areas of recovery-oriented care and priority education to enhance youth recovery. It has demonstrated support for the relevance of CHIME processes in youth recovery and endorsed previous youth recovery research. It has concurred that youth recovery should include caregivers and a more comprehensive range of systemic supports. One of the unique contributions this research has made to understanding youth recovery is the reference to dual perspectives related to recovery: restoration-oriented and resilience-oriented processes (see Tables 5 and 6). This new perspective offers an alternate conceptualisation of youth recovery that encompasses the developmental and ecological aspects relevant to CHIME processes. This study has utilised a co-development process consistent with recovery principles and contributed to understanding youth recovery from a lived experience and multi-systemic perspective. Future research exploring how youth prefer to help seek and engage with MH services would provide direction for the advancement of recovery-oriented service provisions and ROSC and thereby offer opportunities to improve the engagement and reach of those in need.

Data Availability

The data analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to client confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request although restrictions apply to the availability of these data.

Change history

22 November 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01206-8

References

Anthony, W. A. (1993). Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16(4), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095655

Barry, M. M., Clarke, A. M., Jenkins, R., & Patel, V. (2013). A systematic review of the effectiveness of mental health promotion interventions for young people in low and middle income countries. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-835/FIGURES/1

Bauman, A. (2022). Attachment, avoidance, and disenfranchised grief in college students during the Covid-19 pandemic. Regent University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Berger, N. (2018). Recovery oriented systems of care (ROSC). The Official Publication of the Ontario Occupational Health Nurses Association, 37(1), 12–15.

Bilsky, W., & Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Values and personality. European Journal of Personality, 8(3), 163–181. https://doi.org/10.1002/PER.2410080303

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. Sage.

Buchanan, A., Peterson, S., & Falkmer, T. (2014). A qualitative exploration of the recovery experiences of consumers who had undertaken shared management, person-centred and self-directed services. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 8(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-8-23/TABLES/5

Bulanda, J. J., Bruhn, C., Byro-Johnson, T., & Zentmyer, M. (2014). Addressing mental health stigma among young adolescents: Evaluation of a youth-led approach. Health & Social Work, 39(2), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/HSW/HLU008

Burns, J. M., Birrell, E., Bismark, M., Pirkis, J., Davenport, T., Hickie, I., Weinberg, M., & Ellis, L. (2016). The role of technology in Australian youth mental health reform. Australian Health Review, 40, 584–590. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH15115

Carrara, B. S., & Ventura, C. A. A. (2018). Self-stigma, mentally ill persons and health services: An integrative review of literature. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 32(2), 317–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APNU.2017.11.001

Clarke, J., Proudfoot, J., Birch, M.-R., Whitton, A. E., Parker, G., Manicavasagar, V., Harrison, V., Christensen, H., & Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. (2014). Effects of mental health self-efficacy on outcomes of a mobile phone and web intervention for mild-to-moderate depression, anxiety and stress: Secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 272. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0272-1

Corr, C. A., & Corr, D. M. (2012). Key elements in a framework for helping grieving children and adolescents. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 6(2), 142–160. https://doi.org/10.2190/IL6.2.C

Corrigan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2002). The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 9(1), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/CLIPSY.9.1.35

Cote, J. E., & Levine, C. G. (2014). Identity, formation, agency, and culture : A social psychological synthesis. In Identity, Formation, Agency, and Culture (1st ed.). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410612199

Crawford, M. (2020). Ecological systems theory: Exploring the development of the theoretical framework as conceived by Bronfenbrenner. Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices, 4(2), 170. https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100170

Das, J. K., Salam, R. A., Lassi, Z. S., Khan, M. N., Mahmood, W., Patel, V., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2016). Interventions for adolescent mental health: An overview of systematic reviews. The Journal of Adolescent Health : Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 59(4S), S49–S60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.020

Davidson, L., Rowe, M., DiLeo, P., Bellamy, C., & Delphin-Rittmon, M. (2021). Recovery-oriented systems of care: A perspective on the past, present, and future. Alcohol Research Current Reviews, 41(1). https://doi.org/10.35946/arcr.v41.1.09

Demaray, M. K., & Malecki, C. K. (2002). Critical levels of perceived social support associated with student adjustment. School Psychology Quarterly, 17(3), 213–241. https://doi.org/10.1521/SCPQ.17.3.213.20883

Doka, K. J. (1989). Disenfranchised grief: Recognizing hidden sorrow (K. J. Doka (ed.)). Lexington Books/D. C. Heath and Com. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1989-98577-000

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. Norton & Company Inc.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity youth and crisis. Norton & Company Inc.

Erikson, E. H. (1980). Identity and the Life Cycle. Norton & Company Inc.

Friesen, B. J. (2007). Recovery and resilience in children’s mental health: Views from the field. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 31(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.2975/31.1.2007.38.48

Geller, D. A., Wieland, N., Carey, K., Vivas, F., Petty, C. R., Johnson, J., Reichert, E., Pauls, D., & Biederman, J. (2008). Perinatal factors affecting expression of obsessive compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 18(4), 539–540. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2007.0112

Gerlinger, G., Hauser, M., De Hert, M., Lacluyse, K., Wampers, M., & Correll, C. U. (2013). Personal stigma in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A systematic review of prevalence rates, correlates, impact and interventions. World Psychiatry, 12(2), 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1002/WPS.20040

Gibson, K. (2021). What young people want from mental health services: A youth informed approach for the digital age. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429322457

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Simon & Schuster Inc.

Hall, M. A., Dugan, E., Zheng, B., & Mishra, A. K. (2001). Trust in physicians and medical institutions: What is it, can it be measured, and does it matter? The Milbank Quarterly, 79(4), 613–639. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.00223

Hartig, T., Johansson, G., & Kylin, C. (2003). Residence in the social ecology of stress and restoration. Journal of Social Issues, 59(3), 611–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00080

Hartman, L. I., Michel, N. M., Winter, A., Young, R. E., Flett, G. L., & Goldberg, J. O. (2013). Self-stigma of mental illness in high school youth. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 28(1), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573512468846

Heflinger, C. A., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2010). Stigma in child and adolescent mental health services research: Understanding professional and institutional stigmatization of youth with mental health problems and their families. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 37(1–2), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0294-z

Hinshaw, S. P. (2005). The stigmatization of mental illness in children and parents: Developmental issues, family concerns, and research needs. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 46(7), 714–734. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1469-7610.2005.01456.X

Hurst, R., Carson, J., Shahama, A., Kay, H., Nabb, C., & Prescott, J. (2022). Remarkable recoveries: An interpretation of recovery narratives using the CHIME model. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 26(2), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-01-2022-0001/FULL/XML

Jiménez, L., Hidalgo, V., Baena, S., León, A., & Lorence, B. (2019). Effectiveness of structural–strategic family therapy in the treatment of adolescents with mental health problems and their families. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 1255. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH16071255

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Kelly, M., & Coughlan, B. (2019). A theory of youth mental health recovery from a parental perspective. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 24(2), 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/CAMH.12300

Khoury, E. (2019). Recovery attitudes and recovery practices have an impact on psychosocial outreach interventions in community mental health care. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10(560). https://doi.org/10.3389/FPSYT.2019.00560

Kroger, J., & Marcia, J. E. (2011). The identity statuses: Origins, meanings, and interpretations. Handbook of Identity Theory and Research, 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_2

Langer, D. A., & Jensen-Doss, A. (2016). Shared decision-making in youth mental health care: Using the evidence to plan treatments collaboratively. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(5), 821–831. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1247358

Law, H., Gee, B., Dehmahdi, N., Carney, R., Jackson, C., Wheeler, R., Carroll, B., Tully, S., & Clarke, T. (2020). What does recovery mean to young people with mental health difficulties? – “It’s not this magical unspoken thing, it’s just recovery.” Journal of Mental Health, 29(4), 464–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2020.1739248

Leamy, M., Bird, V., Boutillier, C. L., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733

Link, B. G., Cullen, F. T., Struening, E., Shrout, P. E., & Dohrenwend, B. P. (1989). A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American Sociological Review, 54(3), 423. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095613

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00164

Mahlke, C. I., Krämer, U. M., Becker, T., & Bock, T. (2014). Peer support in mental health services. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 27(4), 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000074

Mccauley, C. O., Mckenna, H., Keeney, S., & Mclaughlin, D. (2015). Exploring young adult service users’ perspectives on mental health recovery Short Report. https://core.ac.uk/works/8971930

McGorry, P. D., Mei, C., Chanen, A., Hodges, C., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., & Killackey, E. (2022). Designing and scaling up integrated youth mental health care. World Psychiatry, 21(1), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/WPS.20938

Meadows, S. O., Brown, J. S., & Elder, G. H. (2006). Depressive symptoms, stress, and support: Gendered trajectories from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(1), 99–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10964-005-9021-6

Mitchell, M. B. (2017). “No one acknowledged my loss and hurt”: Non-death loss, grief, and trauma in foster care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 35(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10560-017-0502-8

Naughton, J. N. L., Maybery, D., Sutton, K., Basu, S., & Carroll, M. (2020). Is self-directed mental health recovery relevant for children and young people? International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(4), 661–673. https://doi.org/10.1111/INM.12699

Nawaz, S. (2011). The relationship of parental and peer attachment bonds with the identity development during adolescence. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 5(1), 104–119.

Perkins, R., & Slade, M. (2012). Recovery in England: Transforming statutory services? International Review of Psychiatry, 24(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2011.645025

Perlick, D. A., Rosenheck, R. A., Clarkin, J. F., Sirey, J. A., Salahi, J., Struening, E. L., & Link, B. G. (2001). Adverse effects of perceived stigma on social adaptation of persons diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder. Psychiatric Services, 52(12), 1627–1632. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1627

Piat, M., Sabetti, J., & Bloom, D. (2010). The transformation of mental health services to a recovery-orientated system of care: Canadian decision maker perspectives. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 56(2), 168–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764008100801

Piat, M., Seida, K., & Sabetti, J. (2017). Understanding everyday life and mental health recovery through CHIME. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 21(5), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-08-2017-0034

Preyde, M., MacLeod, K., Bartlett, D., Ogilvie, S., Frensch, K., Walraven, K., & Ashbourne, G. (2019). Youth transition after discharge from residential mental health treatment centers: Multiple perspectives over one year. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 37(1), 65–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2019.1597664

Racine, N., McArthur, B. A., Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Zhu, J., & Madigan, S. (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(11), 1142–1150. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAPEDIATRICS.2021.2482

Rayner, S., Thielking, M., & Lough, R. (2018). A new paradigm of youth recovery: Implications for youth mental health service provision. Australian Journal of Psychology, 70(4), 330–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/AJPY.12206

Rickwood, D. J., Deane, F. P., & Wilson, C. J. (2007). When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? Medical Journal of Australia, 187(S7), S35–S39. https://doi.org/10.5694/J.1326-5377.2007.TB01334.X

Rowling, L. (2012). Developing and sustaining mental health and wellbeing in Australian schools. In S. Kuutcher, Y. Wei, & M. D. Weist (Eds.), School Mental Health (pp. 6–20). Cambridge University Press.

Sheedy, C. K., & Whitter, M. (2013). Guiding principles and elements of recovery-oriented systems of care: What do we know from the research? Journal of Drug Addiction, Education, and Eradication, 9(4), 225–286.

Slade, M. (2012). Recovery research: The empirical evidence from England. World Psychiatry, 11(3), 162. https://doi.org/10.1002/J.2051-5545.2012.TB00119.X

Slade, M., & Longden, E. (2015). Empirical evidence about recovery and mental health. BMC Psychiatry, 15(1), 285. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0678-4

Slade, M., Amering, M., Farkas, M., Hamilton, B., O’Hagan, M., Panther, G., Perkins, R., Shepherd, G., Tse, S., & Whitley, R. (2014). Uses and abuses of recovery: Implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry, 13(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20084

Sommer, J., Gill, K., & Stein-Parbury, J. (2018). Walking side-by-side: Recovery Colleges revolutionising mental health care. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 22(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-11-2017-0050

Tang, I. C., & Wu, H. C. (2012). Quality of life and self-stigma in individuals with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Quarterly, 83(4), 497–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11126-012-9218-2

Tisdale, C., Snowdon, N., Allan, J., Hides, L., Williams, P., & de Andrade, D. (2021). Youth mental health peer support work: A qualitative study exploring the impacts and challenges of operating in a peer support role. Adolescents, 1(4), 400–411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ADOLESCENTS1040030

Walsh, M., Kittler, M. G., Throp, M., & Shaw, F. (2019). Designing a recovery-orientated system of care: A community operational research perspective. European Journal of Operational Research, 272(2), 595–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJOR.2018.05.037

Ward, D. (2014). ‘Recovery’: Does it fit for adolescent mental health? Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 26(1), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.2989/17280583.2013.877465

Warren, J. S., Nelson, P. L., & Burlingame, G. M. (2009). Identifying youth at risk for treatment failure in outpatient community mental health services. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18(6), 690–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10826-009-9275-9

Whitley, R., Shepherd, G., & Slade, M. (2019). Recovery colleges as a mental health innovation. World Psychiatry : Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association, 18(2), 141–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20620

Zuaboni, G., Hahn, S., Wolfensberger, P., Schwarze, T., & Richter, D. (2017). Impact of a mental health nursing training-programme on the perceived recovery-orientation of patients and nurses on acute psychiatric wards: Results of a pilot study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(11), 907–914. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2017.1359350

Acknowledgements

The author(s) would like to acknowledge the Consumers Health Foundation for their provisions and support of this research and all participants for their valued and imperative contributions to this work.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions The author(s) received partial financial support for the research from the Consumers Health Foundation by way of the Youth MH Incubator Grant 2021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VCD and GK researched literature and conceived the study. VCD wrote the first draft of the manuscript. GK, LB, and CdP critically reviewed, added to, and edited the manuscript. AP-S, AA, LW, and YG supported and engaged in the data collection process. KS contributed to the interpretation and analysis of data. LA and BR contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval was obtained through the University of Southern Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (H20REA100) as part of a larger program of research.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of participants under 18 years of age. All participants signed informed consent regarding publishing their data.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: The surname of coauthor Yasmin Groom was misspelled in the article as originally published and has been corrected.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dallinger, V.C., Krishnamoorthy, G., du Plessis, C. et al. Conceptualisation of Personal Recovery and Recovery-Oriented Care for Youth: Multisystemic Perspectives. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01170-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01170-3