Abstract

Adolescents are particularly prone to engage in health-risk behaviors such as alcohol and substance use, which can significantly impact their present and future lives. Our study explores the factors contributing to (1) regular alcohol use (i.e., at least 3 to 5 times in the last 30 days) and (2) binge drinking (i.e., drinking at least five glasses of alcohol in a single sitting in the last 12 months) in adolescents, in the 2014 and 2018 waves of the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children (HBSC) survey conducted in the Lombardy region, Italy. Data collection used a stratified cluster sampling method to obtain a representative sample of adolescents (N = 6506) aged 11, 13, and 15 years (49.7% females). We used structural equation models (SEM) to explore the association of individual-related factors, including health complaints (i.e., somatic problems and psychological problems) and psychosocial variables (i.e., perceived support from family, peers, and teachers), on regular alcohol consumption and binge drinking. Overall, 9.9% of adolescents reported regular alcohol drinking and 18.3% binge drinking. The findings highlighted that higher somatic problems are associated with increased regular alcohol use (OR=1.24, 95% CI: 1.04–1.46), and higher psychological problems are associated with increased binge drinking (OR=1.33, 95% CI: 1.15–1.55). Moreover, lower perceived support from teachers is significantly associated with both regular (OR=1.41, 95% CI: 1.25–1.59) and binge drinking (OR=1.42, 95% CI: 1.28–1.57), and lower perceived student support is associated with a reduced risk of both usual drinking (OR=0.87, 95% CI: 0.77–0.98) and binge drinking (OR=0.86, 95% CI: 0.78–0.96). The study findings emphasize the importance of tackling somatic and psychological health and psychosocial support, particularly in the school environment, through interventions aimed at controlling adolescent drinking habits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Adolescence is a crucial developmental period, roughly ranging from the onset of puberty to the beginning of emerging adulthood (i.e., from 10 to 19 years old) (Singh et al., 2019), where changes co-occur at physical, cerebral, and psychological levels (Casey et al., 2008). Research has shown that adolescents are particularly prone to engage in health-risk behaviors such as tobacco, substance, and alcohol use (Casey et al., 2008; Romer et al., 2017; Spear, 2002); only in the USA, adolescents aged 12 to 17 years accounted for 3.8% of alcohol users (2021 NSDUH Annual National Report | CBHSQ Data). The following sections will delve into the factors influencing adolescent alcohol use, the role of somatic and psychological complaints, and the impact of social support from family, teachers, and peers on these behaviors.

Investigating Alcohol Use in Adolescence

Adolescents are likely to experience unfavorable patterns of alcohol use, consuming up to two or three times more per occurrence than adults (Spear, 2002; Spear & Swartzwelder, 2014). A suggested explanation is that the neural changes characteristic of adolescence promote greater sensitivity to the effects of ethanol and less sensitivity to the potential consequences of its use (Spear & Swartzwelder, 2014). Despite the ban on selling alcoholic beverages to minors, in Italy, the age at which people start drinking is around 12 years (Giustino et al., 2018). Available data suggest that 4.3% of adolescents consume alcohol regularly and are predisposed to binge drinking with comparable levels to the average population among 16–17-year-olds (Indagine conoscitiva sulle dipendenze patologiche diffuse tra i giovani, 2021. In addition, in Northern Italy, consumption levels are higher than in the South (Asciutto et al., 2016). A common definition of binge drinking entails consuming five or more units of alcohol in males per occasion or four or more units in females (Chung et al., 2018). However, it is worth noting that there are debates in the literature, highlighting the difficulty of obtaining a precise assessment of binge drinking (Golpe et al., 2017; Lannoy et al., 2021) and the common under-reporting among individuals (Mongan & Long, 2015).

Somatic and Psychological Determinants of Alcohol Use and Abuse

The literature has highlighted that understanding alcohol use in adolescence requires considering several factors (ENOCH, 2006; Nees et al., 2012). A 2019 meta-analysis of 58 studies highlighted the association of binge drinking with deficits in neurocognition, decision-making, and difficulties in regulating impulses in young drinkers (Lees et al., 2019). Other studies highlighted an association between binge drinking and deficits in working memory (Carbia et al., 2017), verbal memory, and executive functions (principally inhibitory control) (Carbia et al., 2018).

Overall, the research emphasizes the need to investigate the association between alcohol use and adolescents’ physical and psychological health (Charrier et al., 2020; Perasso et al., 2021). Subjective health complaints include somatic and psychological problems (Haugland & Wold, 2001).

Indeed, on the one hand, in adolescence, the presence of somatization of various kinds (i.e., headache and stomachache) is associated with an increased risk of psychopathology (depression, anxiety) (Bohman et al., 2010). “Somatic complaints” refer to physical symptoms experienced by individuals without a confirmed diagnosis, often associated with psychological stress. Such symptoms can include recurring issues like headache, stomachache, fatigue, and other physical discomforts unrelated to a medical condition (Dey et al., 2015). However, literature focusing on the contribution of somatic complaints, often entangled in the broader category of internalizing aspects in general, is still developing (Gårdvik et al., 2021).

On the other hand, numerous contributions highlighted the association of psychological problems with problematic alcohol use in adolescence (Stolle et al., 2009), particularly externalizing problems (i.e., aggression and behavioral dysregulation) (Conrod et al., 2008). In contrast, mixed evidence is available on the association between anxiety and depressive symptoms and problematic alcohol use. For example, the contribution of Edwards et al., (2014) highlighted a negative association between internalizing symptoms and early adolescent alcohol use (Edwards et al., 2014). However, a more recent meta-analysis (2019) considered 12 longitudinal studies, underlining a significant contribution of internalizing problems in childhood and adolescence to the risk of alcohol use disorder in young adults (Meque et al., 2019). Another systematic review found an association between heightened negative emotional states and binge drinking (Lannoy et al., 2021), including greater severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms and difficulties in recognizing emotional cues expressed by others. The study also revealed that, regarding emotional response, binge drinkers exhibit reduced emotional responses compared with non-binge drinkers.

The Contribution of Perceived Social Support Alcohol Use and Abuse

It is crucial to consider interpersonal experiences to understand maladaptive and risky behaviors. A study identified four primary reasons behind regular and excessive alcohol consumption: reducing negative emotions, socializing, conforming to peer groups, and increasing positive emotions (Laghi et al., 2016). Adolescents may initially seek positive experiences through alcohol use, leading to addiction and misuse due to inadequate regulation. In another study exploring the effects of COVID-19 lockdowns on alcohol consumption in Ireland in a population of 18 years old and older, it was found that older age was the primary predictor for increased drinking, with high coping motives and low social drinking motives being significant drivers. These coping motives were further associated with heightened psychopathological symptoms such as depression, loneliness, and anxiety (Carbia et al., 2022).

Perceived social support, specifically a supportive family environment, protects against psychopathology, antisocial behavior, and at-risk behaviors like substance and alcohol use (Buelga & Cava, 2017; Catanzaro & Laurent, 2004; Sharaf et al., 2009). Also, the school context is essential for adolescent experimentation and growth: a supportive relationship with peers and teachers can enhance psychological well-being and mitigate at-risk behaviors (Kiefer et al., 2015; Suldo et al., 2009). During the COVID-19 pandemic, schools were closed, and distance learning at home led to isolation for several months. This lack of a supportive socialization context highlighted the negative impact on adolescents. For example, a recent study found a significant association between trait impulsivity and increased drinking in late adolescents (Amerio et al., 2022), while higher perceived social support was associated with lower alcohol use (Lechner et al., 2020). Conversely, increased school stress is a risk factor for adolescent binge drinking (Chung & Joung, 2018; Desousa et al., 2008; Inguglia et al., 2019).

Aims of the Study

Alcohol use is a widespread phenomenon that significantly impacts adolescents’ present and future lives (Inchley et al., 2020; Spear & Swartzwelder, 2014). Figure 1 graphically illustrates the literature mentioned above. To understand the prevalence of alcohol use in younger generations, this exploratory study aims to investigate the contribution of health complaints and psychosocial determinants on alcohol use in a representative sample of Lombardy region adolescents using the 2014 and 2018 Health Behavior in School-Aged Children (HBSC) waves. More specifically, we aim to investigate two theoretical models for (1) regular alcohol use (i.e., at least 3 to 5 times in the last 30 days) and (2) binge drinking (i.e., drinking at least five glasses of alcohol in a single sitting in the last 12 months) in adolescents, including the concurrent contribution of individual-related factors (i.e., health complaints, thus including somatic and psychological problems) and psychosocial variables that are family-related (i.e., perceived support from parents) and school-related (i.e., perceived support from schoolmates/students and teachers). In line with available findings (Charrier et al., 2020; Inchley et al., 2020), we hypothesized that higher health complaints and lower perceived psychosocial support would enhance the likelihood of both regular alcohol consumption and binge drinking.

Methods

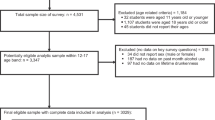

This cross-sectional study is based on the data from the 2014 and 2018 waves of the Lombardy Health Behavior in School-Aged Children (HBSC) survey. Lombardy accounts for one sixth of the national population, with a size comparable to Austria and Sweden (Life in the EU, n.d.). Data collection used a stratified cluster sampling method to obtain representative samples for each age group (11, 13, and 15 years old). School classes were the primary sampling unit, selected from a complete list of public and private schools in Lombardy. More information on the sampling methodology and data collection is available elsewhere (Lazzeri et al., 2021).

Consent was obtained from educational institutions, and informed consent was collected from adolescents and their families, following international guidelines of the HBSC protocol. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethical Board of the National Institute of Health (general protocol: PRE-876/17).

A total of 6506 students (N=3172 from the 2014 wave and N=3372 from the 2018 wave, respectively; F=49.7%; 11 years old= 32.1%, 13 years old= 34.5%, 15 years old= 33.5%), self-reporting information on alcohol use in the previous month, were included in the study.

Measures

Demographics and Control Variables

A structured, standardized questionnaire provided information on sex, parental level of education, family socioeconomic status (using the Family Affluence Scale, FAS) (Hartley et al., 2016), adolescents’ nationality, family members, and the number of siblings. Adolescents also reported their previous weekly physical activity (days/week). They provided information if they had been smoking in the previous month (possible answers ranged from 1= never to 7= 30 days or more). The variable was then dichotomized into (1) never smoked and (2) smoking at least once in the previous month.

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from the adolescents’ self-reported weight (kg) and height (cm). BMI was then categorized into underweight/average weight and overweight/obese using the specific sex and age cutoffs proposed by Cole et al. (Cole et al., 2007).

Regular Alcohol Use and Binge Drinking

In line with the previous HBSC studies (Inchley et al., 2018), we investigated regular alcohol consumption and binge drinking among adolescents.

Alcohol consumption was assessed by asking, “How many days did you drink alcohol (if ever) in the past 30 days?”. Possible answers were (i) never; (ii) 1–2 days; (iii) 3–5 days; (iv) 6–9 days; (v) 10–19 days; (vi) 20–29 days; and (vii) 30 days or more. We defined regular drinkers as those who consumed alcohol three or more days in the previous 30 days (i.e., an average of once a week). The outcome variable was classified as “no regular alcohol use” and “regular alcohol use.”

Binge drinking was assessed by asking, “Consider the past 12 months. Have you ever consumed five or more alcoholic beverages, even different ones, on a single occasion (an evening, a party, alone, etc...)?”. Those who answered “yes” were considered binge drinkers. The outcome variable included was classified as “no binge drinking” and “binge drinking.”

Health Complaints and Subjective Health Perception

The HBSC Symptom Checklist (Haugland & Wold, 2001) assessed health complaints, including two sections rating somatic and psychological complaints over the previous 6 months on a Likert scale from 5 = “approximately every day” to 1 = “rarely or never.” Somatic problems were defined as a latent variable including the following symptoms: headache, stomachache, backache, and feeling dizzy. Psychological problems were defined as a latent variable including the following symptoms: feeling low, being irritable or in a bad mood, being nervous, or experiencing difficulties falling asleep. Higher scores indicated higher health complaints. Latent variables for psychological and somatic problems have been included in a previous HBSC study (Dey et al., 2015).

Perceived Support from Parents, Teachers, and Friends and School Pressure

In line with the previous studies (Benzi et al., 2023; Delaruelle et al., 2021), we included latent variables for psychosocial support in the models.

Family support was calculated as a latent variable including four items, measured on a 7-point Likert scale from 7= “strongly disagree” to 1= “strongly agree”: “My family tries to help,” “I get emotional help from my family,” “I can talk about problems with my family,” and “My family helps me with my decisions.” Higher scores indicated lower support from family. Teacher support was calculated as a latent variable including three items, measured on a 5-point Likert scale from 1= “strongly agree” to 5= “strongly disagree”: “I feel that my teachers accept me as I am,” “I feel that my teachers care about me as a person,” and “I feel I can trust my teachers.” Higher scores indicated lower support from teachers. Student support was calculated as a latent variable including three items, measured on a 5-point Likert scale from 1= “strongly agree” to 5= “strongly disagree”: “The students in my class enjoy being together,” “Most of the students in my class are kind and helpful,” and “Other students accept me as I am.” Higher scores indicated lower support from peers.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using R ver. 2022.07.2 (R Core Team, 2022). Descriptive statistics were used to explore the participants’ general characteristics with the psych package (Revelle & Revelle, 2015). To test the main hypotheses, structural equation modelling (SEM) was performed using the lavaan package (Rosseel et al., 2017).

We computed two models. Model 1 explored the association of latent variables of adolescents’ health (e.g., somatic problems and psychological problems) and perceived psychosocial support (i.e., family support, teacher support, and student support) with regular alcohol consumption (Fig. 2). Model 2 explored the association of latent variables of adolescents’ health (e.g., somatic problems and psychological problems) and perceived psychosocial support (i.e., family support, teacher support, and student support) with binge drinking (Fig. 3).

Model for the associations between somatic problems; psychological problems; perceived support from parents, students, and teachers; and regular drinking. Note. Model was adjusted for sex, age, and data collection wave. Somatic problems and psychological problems: HBSC Symptom Checklist (Haugland & Wold, 2001); family support, student support, and teacher support (Benzi et al., 2023, Delaruelle et al., 2021). Factor loadings for individual items are reported in gray. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. ***p≤.001; **p≤0.01; *p≤0.05

Model for the associations between somatic problems; psychological problems; perceived support from parents, students, and teachers; and binge drinking. Note. Model was adjusted for sex, age, and data collection wave. Somatic problems and psychological problems: HBSC Symptom Checklist (Haugland & Wold, 2001); family support, student support, and teacher support (Benzi et al., 2023, Delaruelle et al., 2021). Factor loadings for individual items are reported in gray. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. ***p≤0.001; **p≤0.01; *p≤0.05

The models’ predictive and explanatory powers were assessed with path coefficients and R2.

All models were calculated using a weighted least square-mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator to account for Likert-based ordinal measurements (Li, 2016). The fit of the model was evaluated by accounting for complementary goodness of fit indices (Ullman & Bentler, 2012): chi-square (χ2) statistic (if p-value related to χ2 is not significant, it means that the model fits with the observed data; however, this statistic is sensitive to sample size and needs to be interpreted adopting a multifaceted approach) (Bollen, 1989); comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) (values ≥ 0.95 indicate a good fit, values ≥ 0.90 indicate an adequate fit); standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) (a value less than 0.08 is generally considered a good fit); and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

All models were adjusted for the wave of data collection, age, and sex contributions (Dey et al., 2015).

To facilitate the interpretation of the binary outcomes, SEM raw regression coefficients were transformed from Q-metric into odds metric (OR = odds ratio) by (1+Q)/(1−Q) (Kupek, 2006).

Results

Among the 6506 young people surveyed, 75.2% reported they had not consumed alcohol in the previous month, 14.9% had consumed it for 1 or 2 days, and 9.9% had consumed it for 3 days or more (Table 1). The prevalence of regular drinkers was highest among 15-year-olds (24.3%) and those who reported having smoked cigarettes at least once in the previous month (42.4%). This prevalence was also slightly higher among males (11.0%) compared to females (8.7%) and adolescents born in Italy (10.0%) compared to those from foreign countries (7.8%). The prevalence of regular users was similar according to their parental highest educational qualification. The prevalence of binge drinking was 18.3%.

Regular Alcohol Use

Model 1 explored the associations of latent variables of adolescents’ health (e.g., somatic problems and psychological problems) and perceived psychosocial support (i.e., family support, teacher support, and student support) with regular alcohol consumption (Fig. 2).

The fit indices of the model were satisfactory: χ2(df) = 810.769 (180), p < 0.001; χ2/df = 4.504; CFI = 0.989; TLI = 0.986; SRMR = 0.028; RMSEA = 0.024 [90% CI (0.022, 0.026)], p > 0.05. Standardized loadings were all significant and positive.

All the model results, including raw regressions and transformed ORs, are reported in Table 2. Higher somatic problems (OR=1.24, 95% CI: 1.04–1.46) and lower perceived support from teachers (OR=1.41, 95% CI: 1.25–1.59) are associated with increased regular alcohol use. Lower perceived student support is associated with a reduced risk of regular drinking (OR=0.87, 95% CI: 0.77–0.98).

The model explained a total variance of 35.2% of regular drinking.

Binge Drinking

Model 2 explored the association of latent variables of adolescents’ health (e.g., somatic problems and psychological problems) and perceived psychosocial support (i.e., family support, teacher support, and student support) with binge drinking (Fig. 3).

The fit indices of the model were satisfactory: χ2(df) = 797.309 (180), p < 0.001; χ2/df = 4.429; CFI = .989; TLI = .987; SRMR = 0.028; RMSEA = 0.024 [90% CI (0.022, 0.025)], p > 0.05.

All the model results, including raw regressions and transformed ORs, are reported in Table 3. Higher psychological problems (OR=1.33, 95% CI: 1.15–1.55) and lower perceived support from teachers (OR=1.42, 95% CI: 1.28–1.57) are associated with increased binge drinking. Moreover, lower perceived student support is associated with a reduced binge drinking (OR=0.86, 95% CI: 0.78–0.96).

The model explained a total variance of 28.3% for binge drinking.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the individual and psychosocial determinants that may promote regular alcohol use and binge drinking in adolescence, gathering data from a representative sample of Italian adolescents from the 2014 and 2018 Health Behavior in School-Aged Children (HBSC) waves.

In our sample, 9.9% of adolescents reported regular drinking. In line with the available evidence, which emphasizes that alcohol consumption can be a risk factor even in low quantities, the importance of considering the high prevalence of this phenomenon in adolescence emerges (Dawson et al., 2008; Spear & Swartzwelder, 2014).

In the first model, we explored the concurrent associations between individual-related factors (i.e., health complaints, thus including somatic and psychological problems), psychosocial variables that are family-related (i.e., perceived support from parents) and school-related (i.e., perceived support from schoolmates/students and teachers), and regular alcohol use in adolescents.

Data showed that adolescents with somatic problems were more likely to engage in regular alcohol consumption, consistent with the previous research linking perceived poor physical health to increased alcohol use among youths. Indeed, data suggest that physical health problems in adolescents might lead to alcohol use as a coping mechanism (Gårdvik et al., 2021). Moreover, when considering psychosocial variables, decreasing support from the teachers enhanced the odds of regular alcohol consumption. This is supported by research that found that lower support from teachers is associated with increased alcohol use in adolescents (Kiefer et al., 2015; Suldo et al., 2009).

In the second model, we explored the concurrent contribution of individual and psychosocial variables to binge drinking among adolescents.

Findings showed that binge drinking might be a maladaptive coping strategy for psychological problems. This result aligns with the previous literature highlighting the role of psychological distress (i.e., anxiety and depression) in understanding excessive alcohol consumption during this developmental period (Pedersen & von Soest, 2015; Stolle et al., 2009).

Moreover, similar to regular alcohol use, perceived support quality from teachers was particularly important for binge drinkers. These findings add to the reflection on binge drinking in adolescence: while much evidence points to the role of peers in exacerbating this phenomenon, the importance for adolescents to feel they can rely on adults in this delicate developmental phase also emerges (Inguglia et al., 2019; Suldo et al., 2009). Indeed, adult support can protect against excessive alcohol use, allowing adolescents to deal with their problems more adaptively, especially in the school environment. This aligns with other HBSC findings highlighting the centrality of perceived social support at school as a space for feeling accepted, supported, and understood (Walsh et al., 2010).

Interestingly, both models highlighted an inverse association between perceived support from students and regular alcohol use or binge drinking, thus suggesting a protective role of lower peer support for these behaviors. These findings might tie in with the literature suggesting a U-shaped relationship between these variables (Nezlek et al., 1994; Peele & Brodsky, 2000; Tinajero et al., 2019). Indeed, literature suggests that individuals with lower social interaction quality might show either lower or higher overall alcohol consumption (i.e., frequency of alcohol consumption or excessive alcohol consumption). Conversely, better-quality peer relationships might be associated with moderate-frequency alcohol consumption. However, this area still needs further investigation to confirm the causality and directionality of these relationships (Tinajero et al., 2019). Thus, while we did not directly measure the quality of social interactions, one possible explanation could be that reduced social interactions, due to lower peer support, might lead to fewer drinking opportunities. Nonetheless, this is speculative and would need further investigation.

Moreover, findings highlighted a differential association between types of alcohol consumption (regular vs. binge drinking) and health complaints (somatic vs. psychological). A potential explanation for the different associations might be a different utility for these behaviors: for example, binge drinking may play a role in the emotional regulation of intense and unmanageable psychological states, which aligns with the available literature (Lannoy et al., 2021). Moreover, regular drinking might be a solution for higher levels of somatization (Steinberg, 2007). Future studies might explore these associations further.

Overall, it is important to consider the limitations of this study when interpreting its results. The cross-sectional study design does not allow for causality to be established between exposures of interest and alcohol use. Also, all data was collected through self-reported surveys. While these measures are easier to administer, especially in particularly lengthy assessments, they are subject to response bias, such as over-reporting. Indeed, adolescents might exaggerate their responses for social desirability bias or misinterpret the questions. Future studies could benefit from semi-structured interviews and intensive longitudinal data collections (ecological momentary assessments) to account for these limitations. Future research should also investigate the long-term effects of health complaints and psychosocial factors on alcohol consumption in adolescents. Additionally, it would be interesting to explore the role of other individual-related and psychosocial determinants, such as peer pressure, parental monitoring, and school connectedness. Also, our sample was drawn only from Italian adolescents; therefore, our findings may not apply to countries with different drinking ages, social norms around alcohol use, or differing levels of socioeconomic development, which might display different patterns of adolescent drinking and associations with health and psychosocial factors. Moreover, our study did not explore the potential variations across gender groups that might influence alcohol consumption patterns; thus, future studies should focus on exploring gender invariance and/or differences in the associations explored. Furthermore, our research used one specific definition of binge drinking, as proposed in the literature (Chung et al., 2018; Donovan, 2009; Golpe et al., 2017). However, it is essential to note that the HBSC questionnaire is not designed to distinguish binge drinking doses for males and females. Thus, given the limitations related to the theoretical framework, the design used, and the inferences made, the results of this study should be interpreted as exploratory. They lay the groundwork for further investigation in larger prospective cohort studies, ideally considering a more diverse range of populations (i.e., HBSC data collections in other countries) and definitions of binge drinking. These limitations underscore the need for caution when generalizing our findings and highlight potential areas for future research to explore.

In conclusion, our study highlighted the significance of considering health complaints and social factors that influence alcohol consumption among teenagers. Our findings reveal the need to focus on adolescents’ physical and mental well-being and provide greater support, particularly from teachers. Additionally, our study suggests a complex relationship between peer interactions and alcohol use, emphasizing the need for further investigation.

Finally, this study is of significant clinical relevance given the high prevalence of adolescent alcohol use and its adverse impacts on adolescents’ health. Indeed, considering these results, it is essential for interventions to reduce alcohol misuse in adolescents to take a comprehensive approach. Rather than focusing solely on the individual, there is a need to incorporate strategies targeting the broader social environment, notably the school setting. Greater emphasis should be placed on the role of teachers and the potential influence they can exert on their students’ alcohol consumption behaviors. As trusted figures in adolescents’ lives, teachers can be leveraged to provide support, promote health education, and encourage healthy coping strategies. Furthermore, the complex interplay between peer relationships and alcohol consumption should be considered when designing prevention and treatment programs.

Overall, our findings strongly advocate for a more tailored approach to tackling adolescent alcohol consumption that encompasses individuals’ physical and psychological health and the broader social environment, particularly in school.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

2021 NSDUH Annual National Report | CBHSQ data. (n.d.). Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2021-nsduh-annual-national-report

Amerio, A., Stival, C., Lugo, A., Fanucchi, T., Gorini, G., Pacifici, R., Odone, A., Serafini, G., & Gallus, S. (2022). COVID-19 lockdown: The relationship between trait impulsivity and addictive behaviors in a large representative sample of Italian adults. Journal of Affective Disorders, 302, 424–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.094

Asciutto, R., Lugo, A., Pacifici, R., Colombo, P., Rota, M., La Vecchia, C., & Gallus, S. (2016). The particular story of Italians’ relation with alcohol: Trends in individuals’ consumption by age and beverage type. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 51(3), 347–353.

Benzi, I. M. A., Gallus, S., Santoro, E., & Barone, L. (2023). Psychosocial determinants of sleep difficulties in adolescence: The role of perceived support from family, peers, and school in an Italian HBSC sample. European Journal of Pediatrics, 182(6), 2625–2634.

Bohman, H., Jonsson, U., Von Knorring, A.-L., Von Knorring, L., Päären, A., & Olsson, G. (2010). Somatic symptoms as a marker for severity in adolescent depression. Acta Paediatrica, 99(11), 1724–1730. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01906.x

Buelga, S., Martínez-Ferrer, B., & Cava, M. (2017). Differences in family climate and family communication among cyberbullies, cybervictims, and cyber bully–Victims in adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.07.017

Carbia, C., Cadaveira, F., López-Caneda, E., Caamaño-Isorna, F., Rodríguez Holguín, S., & Corral, M. (2017). Working memory over a six-year period in young binge drinkers. Alcohol, 61, 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2017.01.013

Carbia, C., García-Cabrerizo, R., Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2022). Associations between mental health, alcohol consumption and drinking motives during COVID-19 second lockdown in Ireland. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 57(2), 211–218.

Carbia, C., López-Caneda, E., Corral, M., & Cadaveira, F. (2018). A systematic review of neuropsychological studies involving young binge drinkers. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 90, 332–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.04.013

Casey, B. J., Getz, S., & Galvan, A. (2008). The adolescent brain. Developmental Review, 28(1), 62–77.

Catanzaro, S. J., & Laurent, J. (2004). Perceived family support, negative mood regulation expectancies, coping, and adolescent alcohol use: Evidence of mediation and moderation effects. Addictive Behaviors, 29(9), 1779–1797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.001

Charrier, L., Natale, C., Dalmasso, P., Alessio, V., Sciannameo, V., Borraccino, A., Lemma, P., Silvia, C., & Berchialla, P. (2020). Alcohol use and misuse: A profile of adolescents from 2018 Italian HBSC data. Annali Dell’Istituto Superiore Di Sanità, 53(4), 531–537.

Chung, S. S., & Joung, K. H. (2018). Risk factors related to binge drinking. The Journal of School Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840518785439

Chung, T., Creswell, K. G., Bachrach, R., Clark, D. B., & Martin, C. S. (2018). Adolescent binge drinking: Developmental context and opportunities for prevention. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 39(1), 5.

Cole, T. J., Flegal, K. M., Nicholls, D., & Jackson, A. A. (2007). Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents: International survey. BMJ, 335(7612), 194. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39238.399444.55

Conrod, P. J., Castellanos, N., & Mackie, C. (2008). Personality-targeted interventions delay the growth of adolescent drinking and binge drinking. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(2), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01826.x

Dawson, D. A., Goldstein, R. B., Chou, S. P., Ruan, W. J., & Grant, B. F. (2008). Age at first drink and the first incidence of adult-onset DSM-IV alcohol use disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 32(12), 2149–2160. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00806.x

Delaruelle, K., Dierckens, M., Vandendriessche, A., Deforche, B., & Poppe, L. (2021). Adolescents’ sleep quality in relation to peer, family and school factors: Findings from the 2017/2018 HBSC study in Flanders. Quality of Life Research, 30(1), 55–65.

Desousa, C., Murphy, S., Roberts, C., & Anderson, L. (2008). School policies and binge drinking behaviours of school-aged children in Wales—A multilevel analysis. Health Education Research, 23(2), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cym030

Dey, M., Jorm, A. F., & Mackinnon, A. J. (2015). Cross-sectional time trends in psychological and somatic health complaints among adolescents: A structural equation modelling analysis of ‘Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children’ data from Switzerland. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(8), 1189–1198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1040-3

Donovan, J. E. (2009). Estimated blood alcohol concentrations for child and adolescent drinking and their implications for screening instruments. Pediatrics, 123(6), e975–e981. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-0027

Edwards, A. C., Latendresse, S. J., Heron, J., Cho, S. B., Hickman, M., Lewis, G., Dick, D. M., & Kendler, K. S. (2014). Childhood internalizing symptoms are negatively associated with early adolescent alcohol use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 38(6), 1680–1688. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12402

Enoch, M.-A. (2006). Genetic and environmental influences on the development of alcoholism: Resilience vs. risk. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094(1), 193–201.

Gårdvik, K. S., Rygg, M., Torgersen, T., Lydersen, S., & Indredavik, M. S. (2021). Psychiatric morbidity, somatic comorbidity and substance use in an adolescent psychiatric population at 3-year follow-up. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(7), 1095–1112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01602-8

Giustino, A., Stefanizzi, P., Ballini, A., Renzetti, D., De Salvia, M. A., Finelli, C., Coscia, M. F., Tafuri, S., & De Vito, D. (2018). Alcohol use and abuse: A cross-sectional study among Italian adolescents. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, 59(2), E167.

Golpe, S., Isorna, M., Barreiro, C., Braña, T., & Rial, A. (2017). Binge drinking among adolescents: Prevalence, risk practices and related variables. Adicciones, 29(4).

Hartley, J. E., Levin, K., & Currie, C. (2016). A new version of the HBSC family affluence scale-FAS III: Scottish qualitative findings from the international FAS development study. Child Indicators Research, 9(1), 233–245.

Haugland, S., & Wold, B. (2001). Subjective health complaints in adolescence—Reliability and validity of survey methods. Journal of Adolescence, 24(5), 611–624.

Inchley, J., Currie, D., Cosma, A., & Samdal, O. (2018). Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study protocol: Background, methodology and mandatory items for the 2017/18 survey. CAHRU.

Indagine conoscitiva sulle dipendenze patologiche diffuse tra i giovani. (2021, May 27). https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/258130

Inguglia, C., Costa, S., Ingoglia, S., & Liga, F. (2019). Associations between peer pressure and adolescents’ binge behaviors: The role of basic needs and coping. The Journal of Genetic Psychology https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00221325.2019.1621259

Kiefer, S. M., Alley, K. M., & Ellerbrock, C. R. (2015). Teacher and peer support for young adolescents’ motivation, engagement, and school belonging. Rmle Online, 38(8), 1–18.

Kupek, E. (2006). Beyond logistic regression: Structural equations modelling for binary variables and its application to investigating unobserved confounders. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 6(1), 1–10.

Laghi, F., Baumgartner, E., Baiocco, R., Kotzalidis, G. D., Piacentino, D., Girardi, P., & Angeletti, G. (2016). Alcohol intake and binge drinking among Italian adolescents: The role of drinking motives. Journal of Addictive Diseases https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10550887.2015.1129703

Lannoy, S., Baggio, S., Heeren, A., Dormal, V., Maurage, P., & Billieux, J. (2021). What is binge drinking? Insights from a network perspective. Addictive Behaviors, 117, 106848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106848

Lannoy, S., Duka, T., Carbia, C., Billieux, J., Fontesse, S., Dormal, V., Gierski, F., López-Caneda, E., Sullivan, E. V., & Maurage, P. (2021). Emotional processes in binge drinking: A systematic review and perspective. Clinical Psychology Review, 84, 101971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.101971

Lazzeri, G., Vieno, A., Charrier, L., Spinelli, A., Ciardullo, S., Pierannunzio, D., Galeone, D., & Nardone, P. (2021). The methodology of the Italian Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) 2018 study and its development for the next round. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, 62(4), 4. https://doi.org/10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2021.62.4.2343

Lechner, W. V., Laurene, K. R., Patel, S., Anderson, M., Grega, C., & Kenne, D. R. (2020). Changes in alcohol use as a function of psychological distress and social support following COVID-19 related University closings. Addictive Behaviors, 110, 106527.

Li, C.-H. (2016). The performance of ML, DWLS, and ULS estimation with robust corrections in structural equation models with ordinal variables. Psychological Methods, 21(3), 369.

Life in the EU. (n.d.). Retrieved September 2, 2022, from https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/key-facts-and-figures/life-eu_en

Meque, I., Dachew, B. A., Maravilla, J. C., Salom, C., & Alati, R. (2019). Externalizing and internalizing symptoms in childhood and adolescence and the risk of alcohol use disorders in young adulthood: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 53(10), 965–975. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867419844308

Mongan, D., & Long, J. (2015). Standard drink measures throughout Europe; Peoples’ understanding of standard drinks. RARHA: Joint Actional on Reducing Alcohol Related Harm.

Nees, F., Tzschoppe, J., Patrick, C. J., Vollstädt-Klein, S., Steiner, S., Poustka, L., Banaschewski, T., Barker, G. J., Büchel, C., Conrod, P. J., Garavan, H., Heinz, A., Gallinat, J., Lathrop, M., Mann, K., Artiges, E., Paus, T., Poline, J.-B., Robbins, T. W., et al. (2012). Determinants of early alcohol use in healthy adolescents: The differential contribution of neuroimaging and psychological factors. Neuropsychopharmacology, 37(4), 4. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2011.282

Nezlek, J. B., Pilkington, C. J., & Bilbro, K. G. (1994). Moderation in excess: Binge drinking and social interaction among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 55(3), 342–351. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1994.55.342

Pedersen, W., & von Soest, T. (2015). Adolescent alcohol use and binge drinking: An 18-year trend study of prevalence and correlates. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 50(2), 219–225.

Peele, S., & Brodsky, A. (2000). Exploring psychological benefits associated with moderate alcohol use: A necessary corrective to assessments of drinking outcomes? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 60(3), 221–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0376-8716(00)00112-5

Perasso, G., Carone, N., Health Behaviour in School Aged Children Lombardy Group 2014, & Barone, L. (2021). Alcohol consumption in adolescence: The role of adolescents’ gender, parental control, and family dinners attendance in an Italian HBSC sample. Journal of Family Studies, 27(4), 621–633.

R Core Team, R. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing.

Revelle, W., & Revelle, M. W. (2015). Package ‘psych.’. The Comprehensive R Archive Network, 337, 338.

Romer, D., Reyna, V. F., & Satterthwaite, T. D. (2017). Beyond stereotypes of adolescent risk taking: Placing the adolescent brain in developmental context. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 27, 19–34.

Rosseel, Y., Oberski, D., Byrnes, J., Vanbrabant, L., Savalei, V., Merkle, E., Hallquist, M., Rhemtulla, M., Katsikatsou, M., & Barendse, M. (2017). Package ‘lavaan.’ Retrieved June, 17(1).

Sharaf, A. Y., Thompson, E. A., & Walsh, E. (2009). Protective effects of self-esteem and family support on suicide risk behaviors among at-risk adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 22(3), 160–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2009.00194.x

Singh, J. A., Siddiqi, M., Parameshwar, P., & Chandra-Mouli, V. (2019). World Health Organization Guidance on ethical considerations in planning and reviewing research studies on sexual and reproductive health in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(4), 427–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.01.008

Spear, L. P. (2002). Alcohol’s effects on adolescents. Alcohol Research & Health, 26(4), 287 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6676689/

Spear, L. P., & Swartzwelder, H. S. (2014). Adolescent alcohol exposure and persistence of adolescent-typical phenotypes into adulthood: A mini-review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 45, 1–8.

Steinberg, L. (2007). Risk taking in adolescence: New perspectives from brain and behavioral science. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(2), 55–59.

Stolle, M., Sack, P.-M., & Thomasius, R. (2009). Binge drinking in childhood and adolescence: Epidemiology, consequences, and interventions. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 106(19), 323. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2009.0323

Suldo, S. M., Friedrich, A. A., White, T., Farmer, J., Minch, D., & Michalowski, J. (2009). Teacher support and adolescents’ subjective well-being: A mixed-methods investigation. School Psychology Review, 38(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2009.12087850

Tinajero, C., Cadaveira, F., Rodríguez, M. S., & Páramo, M. F. (2019). Perceived social support from significant others among binge drinking and polyconsuming Spanish university students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(22), 4506. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224506

Ullman, J. B., & Bentler, P. M. (2012). Structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Psychology (Second ed., p. 2).

Walsh, S. D., Harel-Fisch, Y., & Fogel-Grinvald, H. (2010). Parents, teachers and peer relations as predictors of risk behaviors and mental well-being among immigrant and Israeli born adolescents. Social Science & Medicine, 70(7), 976–984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.010

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the health professionals, teachers, and students involved in the project who made this study possible. HBSC Lombardy focus group: University of Turin, Franco Cavallo; DG Welfare, Liliana Coppola and Corrado Celata; University of Milan, Antonella Delle Fave; University of Milano Bicocca, Elisabetta Nigris, Luca Vecchio, Marco Terraneo, and Mara Tognetti; University of Pavia, Lavinia Barone; University of Insubria, Silvia Salvatore; Polytechnic University of Milan, Stefano Capolongo; Catholic University of Milan, Elena Marta and Edoardo Lozza; Bocconi University, Aleksandra Torbica; IULM University, Vincenzo Russo; Mario Negri Institute, Silvano Gallus and Eugenio Santoro. HBSC Lombardy Committee 2018: regional coordination of HBSC Lombardy Study (DG Welfare of Lombardy Region): Corrado Celata, Liliana Coppola, Lucia Crottogini, and Claudia Lobascio. MIUR-regional school office for Lombardy region: Mariacira Veneruso; regional research group: Giusi Gelmi, Chiara Scuffi, and Veronica Velasco; representatives of health protection agencies: Giuliana Rocca, Paola Ghidini, Ornella Perego, Raffaele Pacchetti, Corrado Celata, Maria Stefania Bellesi, Silvia Maggi, Elena Nichetti; referents of territorial school offices: Antonella Giannellini, Federica Di Cosimo, Mariacira Veneruso, Davide Montani, Marina Ghislanzoni, Carla Torri, Elena Scarpanti, Laura Stampini, Cosimo Scaglione, Angela Sacchi, and Marcella Linda Casalini

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Pavia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The Ethical Committee of the Institutional Ethical Board of the National Institute of Health approved all materials and procedures.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Members of the HBSC Lombardy Committee are available in the “Acknowledgements” section.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Benzi, I.M.A., Stival, C., Gallus, S. et al. Exploring Patterns of Alcohol Consumption in Adolescence: the Role of Health Complaints and Psychosocial Determinants in an Italian Sample. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01159-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01159-y