Abstract

Over 100 million individuals worldwide experience negative outcomes as a function of a family member or loved one’s substance use. Other reviews have summarized evidence on interventions; however, success often depends on the behavior of the individual causing harm, and they may not be ready or able to change. The aim of this study was to identify and describe evaluations of psychosocial interventions which can support those affected by alcohol harm to others independent of their drinking relative or friend. A systematic review/narrative synthesis of articles from 11 databases pre-registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021203204) was conducted. Those experiencing the harm were spouses/partners or adult children/students who have parents with alcohol problems. Studies (n = 7) were from the UK, the USA, Korea, Sweden, Mexico, and India. Most participants were female (71–100%). Interventions varied from guided imagery, cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing, and anger management. Independent interventions may support those affected by another’s alcohol use, although there was considerable variation in outcomes targeted by the intervention design. Small-scale studies suggest psychosocial interventions ease suffering from alcohol’s harm to others, independent of the drinking family member. Understanding affected others’ experience and need is important given the impact of alcohol’s harm to others; however, there is a lack of quality evidence and theoretical underpinning informing strategies to support these individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Over 100 million individuals worldwide experience negative health and social outcomes as a function of a family member’s substance use (Orford et al., 2013). The cost of this harm to others is both substantial and underestimated (Navarro et al., 2011). Karriker-Jaffe et al. (2018) recognize the cost of this harm to others as both a public health issue and a concern at the individual level. We will refer to those affected by harms as “affected others.” Other reviews have summarized evidence on interventions to support affected others; however, the intervention success often is affected by the change in the behavior of the individual causing the harm. This is the first paper to isolate those interventions which are independent of the drinker’s behavior who is causing the harm to the affected other. As the drinkers may not be willing or able to change, it is important to summarize evidence which can support affected others independent of their drinking relative or loved one. This independence is important. It empowers the affected other to heal without requiring their loved one to change (Copello et al., 2000).

The impact of alcohol use on an affected other can be wide ranging (Laslett et al., 2010; Room et al., 2016), occurring at the individual, group, or at societal level (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2018; Wilkinson et al., 2014). For this review, the focus is on the individual level. For affected others, worry is common (Orford et al., 2013) and can lead to long-term impact on physical and mental health (Ray et al., 2009; Timko et al., 2019). Other negative consequences include physical harms (e.g., injuries; traffic accidents; harm from interpersonal violence, aggression and crime; harm to families, including domestic violence and harm to a developing fetus), psychological harms (e.g., psychological distress, marital disharmony), and changes in other aspects of life (e.g., separation and divorce, child or household neglect; finance, work, parenting, and the meeting of other obligations) (Navarro et al., 2011; Room et al., 2017). The harm can result from a single event or multiple occasions (McClatchley et al., 2014; Room et al., 2017).

Several high-quality reviews exist which summarize the nature and effectiveness of interventions for family members affected by an adult relative’s substance use. For example, McGovern et al. (2021) summarized the findings in a systematic narrative review of sixty-five trials which aggregated both those which include family members in the intervention and those that do not, and with those who use alcohol, and those who use other drugs. Overall, they summarized behavioral interventions delivered with the substance user and the affected other could improve outcomes, but the complex “multidimensional adversities” experienced by the drinker and affected other(s) are rarely addressed effectively. We do not know if or how affected others’ experience might differ depending on whether alcohol or drugs were used. Similarly, they concluded that interventions which are solely designed for the affected other but contain some components of behavioral modification directed at the person who is causing the harm rarely served the needs of the affected other (McGovern et al., 2021). In another recent systematic review with meta-analysis, Merkouris et al. (2022) explored affected other interventions across different addictions, demonstrating some effectiveness in improving some characteristics of the experience of harm to others, such as depression, life satisfaction, and coping. Although the aim was to understand affected other interventions, there was some focus on the drinker causing the harm in some of the synthesized work and this expansion facilitated some meta-analysis across addictions. The authors highlighted limitations in the evidence base in terms of capacity and methodological issues.

In acknowledgment that harm to others differs internationally (Wilsnack et al., 2018), and that low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) are often under-represented in reviews, Rane et al. (2017), in their systematic narrative review, focused on interventions for affected others in the LMIC setting. They summarized four articles; some evidence of positive benefit for affected others from alcohol and drugs, but only one reflected an intervention which was independently targeting the affected other (de los Angeles Cruz-Almanza et al., 2006).

The evidence base for interventions which can support an affected other individual without another individual having to change is unclear. Other high-quality reviews have provided evidence for affected other interventions; however, some include interventions which have some roles in changing the drinker causing the harm or combine their findings with other substances/addictive behaviors beyond just alcohol. For those who wish to change on their own, independent of the drinker causing harm, there is a need for a clear evidence base. This evidence base, with a focus only on alcohol, can help us understand if existing interventions are effective and assess the gaps that inform the development of novel psychosocial interventions to address the harm (England et al., 2015). There are no current systematic reviews of this nature. The review provided evidence for the following questions: (1) What is the nature of psychosocial interventions to support adults harmed by others’ drinking? (2) What is the evidence of their efficacy or effectiveness? and (3) What are the outcome measures (primary, secondary, or undefined outcomes) used to show efficacy or effectiveness and how are these measured?

Method

We registered the review protocol in advance on PROSPERO (CRD42021203204) and produced a write-up that followed PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., 2021), with the checklist included in Supplementary Material A. Materials relating to the interim steps of the systematic review are available on the open science framework https://osf.io/fsn9a/. OVID (Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, HMIC), EBSCO (CINAHL, ERIC), Cochrane Library, Scopus, Web of Science,Footnote 1 and SciELO were the databases searched. Other sources were ongoing and registered trials at Clinicaltrials.gov, WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), and the Open Science Framework.Footnote 2 We identified grey literature through CADTH Grey Matters tool, OpenSIGLE (http://www.opengrey.eu), MedNar, and citation and reference searches of included papers. There were no date restrictions. Searches were run in May 2021. Included papers evaluated an intervention which targets the person(s) affected by the alcohol use (affected others) only and did not target the drinker perceived to be causing the harm. Core search concepts related to three domains: alcohol use, psychosocial interventions, and longitudinal quantitative design. The PICO (population, intervention, comparator, outcomes) framework informed the eligibility criteria as outlined below. Terms were coupled with relevant Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)/thesaurus terms; truncated and variant spellings were used to identify useful records. All search terms and results are available on the open science framework. Eligible studies were randomized controlled trials, controlled trials, randomized trials, quasi-experimental trials, and pre-post evaluations of interventions where individuals were evaluated at baseline before intervention and followed up after intervention. For this review, all included studies will report on quantitative outcomes.

Population

The population are adults who are experiencing or have experienced harm as a function of another adult’s unhealthy alcohol use. The harm may have occurred when the person was a child, but they must be currently an adult in their respective publication.

Intervention

The intervention should be psychosocial, that is non-pharmacological in nature, and an intervention which aims to improve health and wellbeing. It should only target the affected other. Interventions which include the drinker or include the affected other adult in the drinker’s treatment will not be included. Interventions which target groups (including families or couples) or at a societal level will be excluded.

Comparator

Comparators could be any active or control intervention or a pre-post design using baseline measures as the comparator.

Outcomes

Description of the interventions according to the elements of the TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) framework (Hoffmann et al., 2014).

Improvement in the affected person’s physical, psychological, or social wellbeing however defined by the outcomes of the project and the target of the intervention. Where possible, we will code interventions for behavior change techniques (Michie et al., 2011, 2014).

Search results were downloaded to EndNote Version X7 (Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA) and de-duplicated. All titles and abstracts were entered in Rayyan software with GWS screening all titles and abstracts, and one of MB, EB, NMM, KUG, SM, and LOH blind second screening results. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. All full-text versions of potentially eligible articles were reviewed by GWS, and all double-screened by one of MB, EB, NMM, KUG, SM, and LOH; discussion resolved discrepancies. Extraction forms were piloted by GWS and KBDC. All data were extracted by GWS and blind double extracted by KBDC. Two reviewers (GWS/KBDC) independently assessed the quality of the eligible studies using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., 2018). The checklist is in Supplementary Material B. Each intervention was coded for Behavior Change Techniques (BCT) by two reviewers (GWS/TE). Where there was a discrepancy in BCT or MMAT coding, these were resolved by discussion amongst both coders.

Results

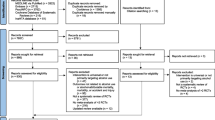

Searches identified 6230 articles (after de-duplication) for eligibility screening by title and abstract. Exclusion at title and abstract stage reflected unambiguous violation of the above PICO criteria based on topic area (i.e., not alcohol), not a quantitative intervention evaluation (e.g., interviews), nor an individual level intervention targeting the affected other (e.g., family or dyadic therapies). Any unclear matches were referred to full-text assessment for closer inspection; 26 articles were retrieved for full-text evaluation against PICO criteria, and 7 were eligible (see Fig. 1 for PRISMA flow chart). The seven included articles contained data on 421 participants, from India, Korea, the USA, the UK, Sweden, and Mexico (Table 1). Three studies were randomized trials (Hansson et al., 2006, 2007; Rychtarik et al., 2015), two were pre-post designs (Aarti et al., 2020; Howells & Orford, 2006), and the rest were quasi-experimental group designs. Two papers were the same population reporting on 12- and 24-month follow-up (Hansson et al., 2006, 2007), and one paper analyzed their sample in two ways: a pre-post case study design and with a quasi-experimental study with a convenience control group (Howells & Orford, 2006). Most papers focused on partners or spouses of people experiencing drinking problems (n = 4); two were adult children of those with alcohol problems (Hansson et al., 2006, 2007), and one was a family member of patients with AUD (Son & Choi, 2010).

Outcomes measured were diverse, the most common were stress, coping, and anger outcomes, although there was little use of similar questionnaires to measure these or other outcomes (Table 1). Other outcomes included affected other’s alcohol use, relational factors with the person drinking, and mental health. Regarding the findings, all but two reported a significant difference in outcomes in a pre-post (Son & Choi, 2010) and quasi-experimental design (de los Angeles Cruz-Almanza et al., 2006). Several reported within-group differences but not between-group differences (de los Angeles Cruz-Almanza et al., 2006; Hansson et al., 2006, 2007). There was some evidence that affected other interventions reduced stress (Aarti et al., 2020; Hansson et al., 2006, 2007; Howells & Orford, 2006), alcohol problems (Hansson et al., 2006, 2007; Howells & Orford, 2006), alcohol use (Hansson et al., 2006, 2007), life being affected (Howells & Orford, 2006), depression (Rychtarik et al., 2015), and anger (Rychtarik et al., 2015); and that interventions increased coping (Aarti et al., 2020; Howells & Orford, 2006), self-esteem (Howells & Orford, 2006), and independence (Howells & Orford, 2006).

The nature of the interventions varied (Table 2). Some interventions used guided imagery (Aarti et al., 2020), rational emotive behavioral therapy (de los Angeles Cruz-Almanza et al., 2006), motivational interviewing (Hansson et al., 2006, 2007), cognitive behavioral models (de los Angeles Cruz-Almanza et al., 2006; Hansson et al., 2006, 2007), anxiety management (Howells & Orford, 2006), coping skills (Hansson et al., 2006, 2007; Rychtarik et al., 2015), and anger management, cultural care theories, or social control theory (Son & Choi, 2010) as the underpinning mechanism. Those studies with control groups or waiting list controls did not detail the nature of what occurred during the wait or in the control group. As some researchers have outlined previously, there can be active ingredients for change in the control group and this may contribute to effects arising from research participation, including that enrolling in a study is a precursor to change for all enrolled (Bendtsen & McCambridge, 2021; Jecks, 2021; Shorter, Bray, et al., 2019).

Interventions were mostly face to face; all had multiple sessions ranging from 3 to 24 sessions. Where time periods were specified, interventions varied from an intensive week of six daily sessions, up to a session a week for 18 weeks. All sessions had some elements of tailoring, which included participants choosing activities on their own, automatic tailoring based on responses to questionnaires, and tailoring of intervention content by therapists. The behaviors targeted by the intervention were alcohol use behavior of the affected other (Hansson et al., 2006, 2007), behaviors arising from anger (Son & Choi, 2010), assertive interpersonal or other communication behaviors (de los Angeles Cruz-Almanza et al., 2006), adaptive coping strategies (Hansson et al., 2006, 2007; Howells & Orford, 2006), and meditation practice (Aarti et al., 2020). Regarding behavior change techniques (BCT), in the seven papers with 11 interventions, two control groups did not describe the details to determine these BCTs (Table 3) (de los Angeles Cruz-Almanza et al., 2006; Son & Choi, 2010). Of the nine with details of interventions, there were 48 BCTs identified, ranging from two in Son and Choi’s anger management program intervention (Son & Choi, 2010) to nine in the Hansson and colleagues’ alcohol intervention and combined interventions (Hansson et al., 2006, 2007). All interventions except Hanssons’ and colleagues coping intervention program (Hansson et al., 2006, 2007) contained 4.1 instruction on how to perform the behavior. Other popular BCTs included 1.2 problem solving (six times), and 6.1 demonstration of the behavior, 8.1 behavioral practice/rehearsal, and 4.2 information about antecedents which appeared four times each.

Discussion

This review aimed to identify psychosocial interventions for affected others in their own right; the evidence base is limited. Only seven studies worldwide were identified, and these were mostly exploratory studies with small sample sizes and of varying qualitiy with MMAT risk of bias scores ranging from 40% to 100%. A more liberal inclusion criteria may have broadened the findings if we included papers which support affected others’ where the substance is a drug other than alcohol such as Carpenter et al. (2020), Copello et al. (2000), Copello et al. (2009), and Velleman et al. (2011). These were deliberately excluded here given the additional complication of substance use and legal matters. Undoubtably, the harm associated with both alcohol and drugs is substantial (Orford et al., 2013) and there is some overlap in harms.

The studies included in this review showed a positive effect of interventions on affected others; however, the use of a diverse range of outcomes limited quantitative synthesis, which appears common in the addiction field (Shorter et al., 2021; Shorter, Heather, et al., 2019). The summary of the findings showed a reduction in psychological and physical distress, reduced anger, and better coping and more assertive behavior. This review found only 16/93 BCTs were used in interventions, and this may be in part due to the lack of detail in the description of some interventions. Many of the interventions evaluated here were modeled on intervention modalities designed for general population mental health (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy) or used in treatment services (e.g., motivational interviewing) rather than being designed for affected others directly. It may also be worth exploring how the alcohol use of the affected other intersects with intervention effectiveness. We also found a predominance of female affected others (Rane et al., 2017; Templeton et al., 2010), which may reflect the excessive burden carried by females. However, males also experience harm from others’ drinking (Sundin et al., 2021) and are too deserving of intervention. Those from white ethnic origin, where ethnicity was reported, also predominated the landscape (Templeton et al., 2010).

There were notable omissions from this review that are commonly considered to be interventions independent of the drinker; however, they did not meet the inclusion criteria of this review. For example, the “pressure to change” model by Barber and colleagues (Barber & Crisp, 1995; Barber & Gilbertson, 1996, 1998) provides assessment and feedback to the affected other but works with them to develop skills to improve the consumption behaviors of the drinker. Notable other exceptions such as Tiburcio Sainz and Natera Rey (2003) or Osilla et al. (2018) also focus on coping independently of the drinker, but the intervention is designed with added outcomes/activities related to the behavior of the drinker. These and other interventions were excluded here,as even if the drinker is not directly involved, the intervention changes their behavior specifically. Group interventions directly working with individuals, such as Al Anon, were also excluded, as they rely on other people for the therapeutic benefit. We also excluded interventions which have a family orientation; others have noted family being important in certain cultures for health change and behavioral interventions (Rane et al., 2017). Whilst there has been criticism leveled at the alcohol treatment field and its commissioners for not adequately including family members in service delivery (Orford et al., 2013), the health and wellbeing of the affected individual cannot depend on the change of behavior of another, and it has been suggested that increasing the treatment engagement of the drinker may not benefit the affected other (McGovern et al., 2021).

Despite an increase in attention on alcohol’s harm to others, there has been little attention on interventions which support affected others, regardless of what the drinker who may cause harm is doing. There are several implications for this in practice. First, there is some evidence supporting individuals who are experiencing harm can improve their stress, quality of life, mental health, coping, self-esteem, social support, and independence. Anger was also reduced in some interventions. Second, we must support individuals who wish to improve their psychological wellbeing, so that their chances of improving their health do not depend on another person to change. Third, more research in this area is required, and the field should integrate to allow for comparable interventions and outcomes to create a high-quality body of evidence. Larger scale trials, with due attention to risk of bias, are also required to improve the quality of the evidence. Fourth, the diversity of outcomes and behavioral targets in interventions is of concern; international and synthesized qualitative work may help to prioritize targets for intervention; however, it must be cautious to cultural diversity in international works. There were six countries included in this review, who have diverse populations, and more attention could be paid to intersectional identities and how personal characteristics might influence outcomes for affected others. Co-designed approaches to interventions may support the acceptability and uptake in future trials (Giebel et al., 2022). Finally, the target population may also need to be diversified; non-white, and non-female populations are under-represented, yet still experience harm from others’ alcohol. This is not to say we should not survey white or female identifying populations, but that we should expand our samples to represent the populations who may also experience this kind of harm.

Individuals and society carry a substantial burden from alcohol’s harms to others. Despite this, interventions which could reduce this burden are severely under researched. More work is required to improve the evidence base and intervention development (Public Health England, 2019) particularly to help and support those who experience the harm from others’ alcohol use without the drinker having to change. The field is in its infancy and needs urgent attention of researchers and policy makers, exploring mechanisms of change and developing a consensus on which outcomes are important, such as for other ABI interventions (Shorter et al., 2021; Tiburcio et al., 2022). We need to do more work to establish the cost-effectiveness of interventions and to understand how an intervention can ease some of the cost of alcohol’s harm to others. Navarro et al. (2011) also emphasized this. This would make the case for investment in interventions to support others and tackle the costs associated with other people’s alcohol use in line with a wider public health perspective. In summary, whilst there is some early evidence that interventions can be successful in supporting the affected other independent of the drinker, new interventions are warranted, which are carefully designed, theoretically informed, appropriately powered, in diverse samples representing the populations from which they are drawn, and appropriately evaluated including effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

Data Availability

All data is available in the article, the supplementary materials, or on the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/fsn9a/.

Notes

Includes Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, Arts & Humanities Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index and Emerging Sources Citation Index.

Note two protocol amendments: (1) remove Google Scholar as a database as records cannot be downloaded for processing, and (2) AMED was not searched as the lead institution no longer has access to this database.

References

Aarti, Srinivasan, P., Manpreet, S., & Jyoti, S. (2020). Effectiveness of guided imagery on stress and coping among wives of alcoholics- A quasi experimental one group pre-test post-test research design. Medico Legal Update, 20(3), 367–374. https://doi.org/10.37506/mlu.v20i3.1424

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck depression inventory-II. Psychological Corporation. https://doi.org/10.1037/t00742-000

Barber, J. G., & Crisp, B. R. (1995). The ‘pressures to change’approach to working with the partners of heavy drinkers. Addiction, 90(2), 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90226912.x

Barber, J. G., & Gilbertson, R. (1996). An experimental study of brief unilateral intervention for the partners of heavy drinkers. Research on Social Work Practice, 6(3), 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973159600600304

Barber, J. G., & Gilbertson, R. (1998). Evaluation of a self-help manual for the female partners of heavy drinkers. Research on Social Work Practice, 8(2), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973159800800201

Bendtsen, M., & McCambridge, J. (2021). Causal models accounted for research participation effects when estimating effects in a behavioral intervention trial. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 136, 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.008

Carpenter, K. M., Foote, J., Hedrick, T., Collins, K., & Clarkin, S. (2020). Building on shared experiences: The evaluation of a phone-based parent-to-parent support program for helping parents with their child’s substance misuse. Addictive Behaviors, 100, 106103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106103

Chon, K. K. (1996). Development of the Korean state-trait anger expression inventory. Korean Journal of Rehabilitation Psychology, 3(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/t06202-000

Coopersmith, S. (1981). Self-esteem inventories. Consulting Psychologists Press. https://doi.org/10.1037/t06456-000

Copello, A., Templeton, L., Krishnan, M., Orford, J., & Velleman, R. (2000). A treatment package to improve primary care services for relatives of people with alcohol and drug problems. Addiction Research, 8(5), 471–484. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066350009005591

Copello, A., Templeton, L., Orford, J., Velleman, R., Patel, A., Moore, L., MacLeod, J., & Godfrey, C. (2009). The relative efficacy of two levels of a primary care intervention for family members affected by the addiction problem of a close relative: A randomized trial. Addiction, 104(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02417.x

de los Angeles Cruz-Almanza, M., Gaona-Márquez, L., & Sánchez-Sosa, J. J. (2006). Empowering women abused by their problem drinking spouses: Effects of a cognitive-behavioral intervention. Salud Mental, 29(5), 25–31. https://revistasaludmental.mx/index.php/salud_mental/article/view/1125.

Derogatis, L. R. (1977). SCL-90-R. Administration, scoring and procedures. Manual for the revised version and other instruments of the psychopathology rating series. School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University.

England, M. J., Butler, A. S., & Gonzalez, M. L. (2015). Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: A framework for establishing evidence-based standards. National Academy Press Washington.

Feinn, R., Tennen, H., & Kranzler, H. R. (2003). Psychometric properties of the short index of problems as a measure of recent alcohol-related problems. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 27(9), 1436–1441. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.alc.0000087582.44674.af

Gambrill, E. D., & Richey, C. A. (1975). An assertion inventory for use in assessment and research. Behavior Therapy, 6(4), 550–561. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7894(75)80013-x

Giebel, C., Zuluaga, M. I., Saldarriaga, G., White, R., Reilly, S., Montoya, E., Allen, D., Liu, G., Castaño-Pineda, Y., & Gabbay, M. (2022). Understanding post-conflict mental health needs and co-producing a community-based mental health intervention for older adults in Colombia: A research protocol. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07645-8

Hansson, H., Rundberg, J., Zetterlind, U., Johnsson, K. O., & Berglund, M. (2006). An intervention program for university students who have parents with alcohol problems: A randomized controlled trial. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 41(6), 655–663. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agl057

Hansson, H., Rundberg, J., Zetterlind, U., Johnsson, K. O., & Berglund, M. (2007). Two-year outcome of an intervention program for university students who have parents with alcohol problems: A randomized controlled trial. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 31(11), 1927–1933. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00516.x

Hoffmann, T. C., Glasziou, P. P., Boutron, I., Milne, R., Perera, R., Moher, D., Altman, D. G., Barbour, V., Macdonald, H., Johnston, M., Lamb, S. E., Dixon-Woods, M., McCulloch, P., Wyatt, J. C., Chan, A. W., & Michie, S. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. Bmj, 348, g1687. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687

Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., & O’Cathain, A. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

Howells, E., & Orford, J. (2006). Coping with a problem drinker: A therapeutic intervention for the partners of problem drinkers, in their own right. Journal of Substance Use, 11(1), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500142459

Jecks, M. (2021). Alcohol use in people who are unemployed: Designing and testing a targeted alcohol brief intervention [PhD Thesis]. The University of Liverpool (United Kingdom). https://doi.org/10.17638/03138167

Karriker-Jaffe, K. J., Room, R., Giesbrecht, N., & Greenfield, T. K. (2018). Alcohol’s harm to others: Opportunities and challenges in a public health framework. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(2), 239–243. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2018.79.239

Kellner, R., Kelly, A. V., & Sheffield, B. F. (1968). The assessment of changes in anxiety in a drug trial: A comparison of methods. The British Journal of Psychiatry : the journal of Mental Science, 114(512), 863–869. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.114.512.863

Laslett, A.-M., Catalano, P., Chikritzhs, T., Dale, C., Doran, C., Ferris, J., Jainullabudeen, T., Livingston, M., Matthews, S., & Mugavin, J. (2010). The range and magnitude of alcohol’s harm to others. FARE Australia. Available from: https://fare.org.au/wp-content/uploads/The-Range-and-Magnitude-of-Alcohols-Harm-to-Others.pdf

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u

McClatchley, K., Shorter, G. W., & Chalmers, J. (2014). Deconstructing alcohol use on a night out in England: Promotions, preloading and consumption. Drug and Alcohol Review, 33(4), 367–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12150

McGovern, R., Smart, D., Alderson, H., Araújo-Soares, V., Brown, J., Buykx, P., Evans, V., Fleming, K., Hickman, M., & Macleod, J. (2021). Psychosocial interventions to improve psychological, social and physical wellbeing in family members affected by an adult relative’s substance use: A systematic search and review of the evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1793. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041793

Merkouris, S. S., Rodda, S. N., & Dowling, N. A. (2022). Affected other interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis across addictions. Addiction, 117(9), 2393–2414. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15825

Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

Michie, S., Atkins, L., & West, R. (2014). The behaviour change wheel: A guide to designing interventions. Silverback Publishing.

Navarro, H. J., Doran, C. M., & Shakeshaft, A. P. (2011). Measuring costs of alcohol harm to others: A review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 114(2–3), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.009

Orford, J., Guthrie, S., Nicholls, P., Oppenheimer, E., Egert, S., & Hensman, C. (1975). Self-reported coping behavior of wives of alcoholics and its association with drinking outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 36(9), 1254–1267. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1975.36.1254

Orford, J., Rigby, K., Miller, T., Tod, A., Bennett, G., & Velleman, R. (1992). Ways of coping with excessive drug use in the family: A provisional typology based on the accounts of 50 close relatives. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 2(3), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2450020302

Orford, J., Natera, G., Davies, J., Nava, A., Mora, J., Rigby, K., Bradbury, C., Bowie, N., Copello, A., & Velleman, R. (1998). Tolerate, engage or withdraw: a study of the structure of families coping with alcohol and drug problems in South West England and Mexico City. Addiction, 93, 1799–1813. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931217996.x

Orford, J., Velleman, R., Natera, G., Templeton, L., & Copello, A. (2013). Addiction in the family is a major but neglected contributor to the global burden of adult ill-health. Social Science and Medicine, 78, 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.036

Osilla, K. C., Trail, T. E., Pedersen, E. R., Gore, K. L., Tolpadi, A., & Rodriguez, L. M. (2018). Efficacy of a web-based intervention for concerned spouses of service members and veterans with alcohol misuse. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 44(2), 292–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12279

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

Public health England. (2019). The range and magnitude of alcohol’s harm to others: A report delivered to the Five Nations Health Improvement Network. Public Health England. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/806935/Alcohols_harms_to_others-1.pdf

Rane, A., Church, S., Bhatia, U., Orford, J., Velleman, R., & Nadkarni, A. (2017). Psychosocial interventions for addiction-affected families in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Addictive Behaviors, 74, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.015

Ray, G. T., Mertens, J. R., & Weisner, C. (2009). Family members of people with alcohol or drug dependence: Health problems and medical cost compared to family members of people with diabetes and asthma. Addiction, 104(2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02447.x

Room, R., Laslett, A.-M., & Jiang, H. (2016). Conceptual and methodological issues in studying alcohol’s harm to others1. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 33(5–6), 455–478.

Room, R., Laslett, A.-M., & Jiang, H. (2017). Conceptual and methodological issues in studying alcohol’s harm to others. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 33(5–6), 455–478. https://doi.org/10.1515/nsad-2016-0038

Rychtarik, R. G., & McGillicuddy, N. B. (1997). The spouse situation inventory: A role-play measure of coping skills in women with alcoholic partners. Journal of Family Psychology, 11(3), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.11.3.289

Rychtarik, R. G., McGillicuddy, N. B., & Barrick, C. (2015). Web-based coping skills Training for women whose partner has a drinking problem. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(1), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000032

Tiburcio Sainz, M., & Natera Rey, G. (2003). Evaluación de un modelo de intervención breve para familiares de usuarios de alcohol y drogas. Un estudio piloto. Salud Mental, 26(5), 33–42.

Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., De la Fuente, J. R., & Grant, M. (1993). Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x

Shorter, G. W., Bray, J. W., Giles, E. L., O’Donnell, A. J., Berman, A. H., Holloway, A., Heather, N., Barbosa, C., Stockdale, K. J., Scott, S. J., Clarke, M., & Newbury-Birch, D. (2019). The variability of outcomes used in efficacy and effectiveness trials of alcohol brief interventions: A systematic review. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 80(3), 286–298. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2019.80.286

Shorter, G. W., Heather, N., Bray, J. W., Berman, A. H., Giles, E. L., O’Donnell, A. J., Barbosa, C., Clarke, M., Holloway, A., & Newbury-Birch, D. (2019). Prioritization of outcomes in efficacy and effectiveness of alcohol brief intervention trials: International multi-stakeholder e-Delphi consensus study to inform a core outcome set. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 80(3), 299–309. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2019.80.299

Shorter, G. W., Bray, J. W., Heather, N., Berman, A. H., Giles, E. L., Clarke, M., Barbosa, C., O’Donnell, A. J., Holloway, A., Riper, H., Daeppen, J. B., Monteiro, M. G., Saitz, R., McNeely, J., McKnight-Eily, L., Cowell, A., Toner, P., & Newbury-Birch, D. (2021). The “Outcome Reporting in Brief Intervention Trials: Alcohol” (ORBITAL) core outcome set: International consensus on outcomes to measure in efficacy and effectiveness trials of alcohol brief interventions. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 82(5), 638–646. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2021.82.638

Spielberger, C. D. (1999). STAXI-2: State-trait anger expression inventory-2. Psychological Assessment Resources. Chicago.

Sobell, L. C., & Sobell, M. B. (1996). Timeline followback (TLFB) user's guide a calendar method for assessing alcohol and drug use. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1037/t06202-000

Son, J.-Y., & Choi, Y.-J. (2010). The effect of an anger management program for family members of patients with alcohol use disorders. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 24(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2009.04.002

Sundin, E., Galanti, M. R., Landberg, J., & Ramstedt, M. (2021). Severe harm from others’ drinking: A population-based study on sex differences and the role of one’s own drinking habits. Drug and Alcohol Review, 40(2), 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13202

Templeton, L., Velleman, R., & Russell, C. (2010). Psychological interventions with families of alcohol misusers: A systematic review. Addiction Research and Theory, 18(6), 616–648. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066350903499839

Tiburcio, M., Monteiro, M. G., Shorter, G. W., Martínez-Vélez, N., Ronzani, T., & Maiga, L. A. (2022). Prioritizing variables for evaluating the efficacy and effectiveness of brief interventions for reducing alcohol consumption: A Latin American perspective. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 83(1), 153–158. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2022.83.153

Timko, C., Grant, K. M., & Cucciare, M. A. (2019). Functioning of concerned others when adults enter treatment for an alcohol use disorder. Alcohol: Clinical and Experimental Research, 43(9), 1986–1993. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14153

Undén, A. L., & Orth-Gomér, K. (1989). Development of a social support instrument for use in population surveys. Social Science & Medicine, 29(12), 1387–1392. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(89)90240-2

U.S. Department of Transportation. (1994). Computing a BAC estimate: Traffic Tech, NHTSA Technology Transfer Series.

Velleman, R., & Orford, J. (1990). Young adult offspring of parents with drinking problems: Recollections of parents' drinking and its immediate effects. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 29, 297–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1990.tb00887.x

Velleman, R., Orford, J., Templeton, L., Copello, A., Patel, A., Moore, L., Macleod, J., & Godfrey, C. (2011). 12-month follow-up after brief interventions in primary care for family members affected by the substance misuse problem of a close relative. Addiction Research and Theory, 19(4), 362–374. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2011.564691

Wilkinson, C., Laslett, A.-M., Ferris, J., Livingston, M., Mugavin, J., Room, R., & Callinan, S. (2014). The range and magnitude of alcohol’s harm to others study: Study methodology and measurement challenges. Australasian Epidemiologist, 21(2), 12–16. https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/informit.791929727584962.

Wilsnack, R. W., Kristjanson, A. F., Wilsnack, S. C., Bloomfield, K., Grittner, U., & Crosby, R. D. (2018). The harms that drinkers cause: Regional variations within countries. International Journal of Alcohol and Drug Research, 7(2), 30–36. https://doi.org/10.7895/ijadr.254

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

MB owns a private company (Alexit AB) which develops and distributes digital lifestyle interventions to the general public and for health care settings. Alexit AB had no part in funding, planning, or execution of this study. All others have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Registration: PROSPERO review registration (CRD42021203204) on April 2021 before review start.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shorter, G.W., Campbell, K.B.D., Miller, N.M. et al. Few Interventions Support the Affected Other on Their Own: a Systematic Review of Individual Level Psychosocial Interventions to Support Those Harmed by Others’ Alcohol Use. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01065-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01065-3